–2–

Residence Rules: Development and Interpretation

EVERY 10 YEARS, the decennial census data provide the means to assess the size and dynamics of communities and social groups. The data are put to myriad uses every day. However, as complicated as the census is and as varied as its uses are, it is not an exaggeration to say that the census relies fundamentally on the core concept of residence. In the end, each census stands or falls on its ability to gather accurate information on how many people live in particular structures at specific geographic locations; all other questions in the census and the information they elicit are secondary to getting residence information right.

Residence rules form a crucial connective link in the census process, taking the data and attributes of each American resident and producing results that can be tabulated by whatever geographic boundaries may be needed. Residence rules are critical to assigning each person to a “correct” address; a second key linkage—between the address and a specific geographic location—is provided by the Census Bureau’s Master Address File (MAF) and geographic database systems. Properly understood and executed, residence rules provide structure to the highly complex task of census data collection.

The specific residence rules used in the census have changed with time; so, too, has the role of residence rules changed, as the census has come to rely on mail-based, self-administered forms in recent censuses. In this chapter, we discuss the broad context of residence in the census, discussing the nature and scope of residence rules (Sections 2–A and 2–B). We also discuss the

general problem of why the seemingly simple topic of residence can be so dauntingly complex to both census designers and respondents (Sections 2–C and 2–D). We outline some of the consequences of difficulties in defining residence in Section 2–E, and close in Section 2–F with a description of the Census Bureau’s preliminary residence rules for 2010.

2–A

WHY ARE RESIDENCE RULES NEEDED?

The explicit constitutional mandate for the decennial census is the generation of counts used to apportion the U.S. House of Representatives. Through this action—assignment of the number of seats in the House and, accordingly, the number of votes in the electoral college for president—representative power is distributed among the states. Hence, the accurate placement of residents by their geographic location (at least to the state level) has always been key to the accuracy of the census.

A related use of census data—and arguably as primary a use as apportionment—is the division of states into legislative and voting districts. The use of the census for redistricting greatly heightens the need for accurate links between people and geographic locations: the redrawing of districts demands data at the fine-grained resolution of blocks and tracts. According to McMillen (2000b), in the early days of the country, the division of states into legislative areas (redistricting) was left primarily to the states. In 1842, Congress enacted a law requiring states with more than one legislative district to divide the state into districts with one representative per district. However, nothing was said about district size until the latter half of the 1800s, when geographical compactness and equal population emerged as requirements. In 1929, Congress passed a permanent apportionment act that contained no directives on the geographic size or population of districts, beginning a period of great variability in legislative districts. This period lasted until the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in 1962 (Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186) that required legislative districts within states to be drawn to include equal numbers of people (McMillen, 2000b). In the wake of that ruling, and other cases that reinforced the “one person, one vote” standard, legislative redistricting is now based entirely on the most recent decennial census counts, and districts are held to exacting standards of numerical equivalence in population. Since 1965, enforcement of the Voting Rights Act and protection of minority rights have also depended on census counts.

Another important use of census counts is in the distribution of funds by the federal government to the states and substate units. In 1998, $185 billion in federal aid was distributed to states and substate areas based in whole or part on census counts (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1999).

In all of these uses of census data, the need to count each person once,

only once, and in the right place, is crucial. Yet the ideal goal—unequivocally linking each person’s census record to a single specific geographic location—is difficult to achieve in practice. Accordingly, the census relies on a set of residence rules to define what “in the right place” means for various census respondents, so that their census returns can be accurately tabulated. Because they are meant to establish the “correct” location of a person in the census context, residence rules can help alleviate problems of duplication; however, as we will describe, residence rules alone can not solve all problems of census error.

2–B

WHAT ARE THE RESIDENCE RULES?

As they have developed over time, the residence rules for the decennial census are a formal list of clarifications and interpretations, indicating where people in various residence situations should be counted in the census. In recent censuses, the actual list of residence rules has been an internal Census Bureau document, although a somewhat edited version of the rules was posted on the Census Bureau Web site during the 2000 census.1 The rules were also incorporated in some form into the training materials for census enumerators. The formal residence rule list is used to answer questions, both inside and outside the Census Bureau, on residence questions (U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, 2004).

To understanding residence rules, it is important to remember what the residence rules are not:

-

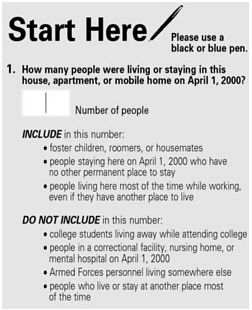

Most fundamentally, the residence rules are not the specific instructions on the census questionnaire—the guidance to census respondents on who should be included or excluded on the census form, such as those on the 2000 census questionnaire (see Figure 2-1). Confusion on this point may arise because the instructions and questions on the census form are the general public’s primary point of interaction with the census residence rules. However, the instructions are only an extract from the full set of residence rules.

-

Residence rules are not the link between a housing unit and a specific geographic location; rather, they provide the link between an individual person (and data about that person, on the questionnaire) and a specific housing unit. The specific geographic referencing between housing units and geographic locations is done through the Census Bureau’s

|

1 |

The presence of these rules online was indicated in a press release detailing the mass mailing of census questionnaires: “a complete set of residency rules telling where students, nursing home residents, military personnel, ‘snowbirds’ and others are counted can be found on the Census Bureau’s Internet site at http://www.census.gov/population/www/censusdata/resid_rules.html” (the link was still functional as of 6/1/06); see U.S. Department of Commerce (2000). |

Figure 2-1 Basic residence question (Question 1), 2000 census questionnaire

-

MAF and geographic reference database, which we discuss in greater detail in Section 8–A.

-

Despite their name, the residence rules are not rules in any legal or regulatory sense. Residence rules are not written into census law; indeed, as we discuss below, not even the term “usual residence” (much less its definition) is written into active census law. Rather, the residence rules are guidelines, internal to the Census Bureau, on how certain living situations should be handled in terms of defining “usual residence.”

2–B.1

Historical Development

While the U.S. Constitution specifies that a census be conducted every 10 years for the purpose of reapportioning the U.S. House of Representatives, it offers no further guidance on exactly how the count is to be performed.2 The first U.S. Congress faced the practical problem of performing a count through the Act of March 1, 1790. That act authorized marshals to carry out

a count such that “every person whose usual place of abode shall be in any family on [August 1, 1790,] shall be returned as of such family.” In addition, “every person, who shall be an inhabitant of any district, but without a settled place of residence, [shall be counted] in that division where he or she shall be on” August 1, and “every person occasionally absent at the time of the enumeration [shall be counted] as belonging to that place in which he usually resides in the United States” (1 Stat. 101, §5).3 The legislative text of 1790 outlined the rules for defining residence for census purposes, with the goal of counting each resident of the United States once and only once and in the correct location; the first census residence rules, like the underlying census goal, have guided every subsequent census.

For most people—in 1790, as in 2006—the meaning of “usual residence” is clear.4 These people are affiliated with only one address or household, and have no difficulty identifying it. Indeed, the inaugural census of 1790 presumed that the concept was sufficiently self-evident that the marshals charged with obtaining the counts through personal contact with residents were provided with no written rules or instructions.

Yet even in the earliest days of the census, conceptual problems with “usual residence” were evident; as Clemence (1987:18) comments, “the [first] census law contained about 1,600 words and not a single definition.” Moreover, ambiguous residential situations were as plentiful in those days as in modern times. Notably, Clemence (1987:12–14) cites the cases of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, who served as president and secretary of state during the official period of conduct for the 1790 census (August 2, 1790–April 1791). In those 36 weeks, Clemence observes that Washington “was on the road for 16 weeks, visiting every State in the Union from Rhode Island to Georgia; 15 weeks at the seat of Government, and only 10 weeks at his home in Mount Vernon, Virginia,” yet he was almost certainly counted as head of family at Mount Vernon. Likewise, Jefferson spent most of that period in Philadelphia: “he, like many others, was following the seat of Government around, which had no settled place of residence for itself.” His name appears twice in 1790 census records—once at his Monticello home in Virginia (where he seems to have been tallied) and once in Philadelphia, where both he and attorney general Edmund Randolph signed a census schedule posted on a tavern wall posted (as the law directed) so that people who believed they were not listed at home could still be registered. More generally, Clemence (1987:19) concludes:

In 1790, there were at least a few Americans abroad, including Thomas Jefferson until his summer voyage home from France. There were people in institutions, people with two homes, riverboat captains with no settled place of residence, militia on post duty in the territories outside of any State, and college students attending, for example, Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and William and Mary.

The first few decennial censuses did not include definitions or residence rules; indeed, even the exact layout of the schedule used by marshals to conduct the count varied by state. The first set of detailed instructions that touched on residence concepts accompanied the 1850 census.5 The 1850 census instructions were the first to specify residence rules (albeit not formally listed or labeled as such) in order to adapt to changing social conditions. Among the emergent residence rules developed for the 1850 census was a determination on where to count college students (Clemence, 1987:21):

Students in colleges, academies, or schools, when absent from the families to which they belong, are to be enumerated only as members of the families6 in which they usually boarded and lodged on [Census Day].

“Because no uniform rule was adopted for the whole United States” regarding the counting of crews of marine vessels, the 1850 instructions continued, “errors necessarily occurred in the last census in enumerating those employed in navigation”; accordingly, the instructions laid out new counting rules that “assistant marshals are required to be particular in following” (Gauthier, 2002:10). Later censuses continued to add rules and instructions for the counting of different groups, typically in response to questions and ambiguities experienced in the field.

Though specific residence rules have shifted over the years, as has the date of the census (see Box 2-1), the “usual residence” benchmark inherited from 1790 has generally prevailed as the underlying residence concept for the census. Even though the concept is enshrined in census practice, there exists no definition of “usual residence” in current census law (Title 13 of the U.S. Code). Moreover, Title 13 does not directly specify what residence standard—a de jure enumeration based on usual residence or a de facto count based on current residence or where a person is found on Census Day—should apply to the decennial census.

|

5 |

Charged with conduct of the 1820 census during his service as secretary of state, future president John Quincy Adams did provide detailed instructions—and, for the first time, a printed list of questions to be asked by the census—but did not expand on the definition of residence. However, his instructions did ask for information about each person’s settled place of residence and family members temporarily absent; “all of the questions refer to the day when the enumeration is to commence,” and enumerators were cautioned to include family members who had died and exclude babies born after Census Day (Clemence, 1987:21). |

|

6 |

As discussed in Section 2–C.1, censuses of this period interpreted “family” as any collective of people in a “dwelling house,” without regard to kinship. Hence, the wording of this rule is tantamount to counting students at their college locations. |

|

Box 2-1 Why Is April 1 “Census Day”? As Anderson (1988:44) notes, “census takers always knew that the count could be affected by the month of the year it was taken.” Early American censuses had to balance the difficulty of making personal contact with residents (slowly, with transportation by foot or horseback) with the prospects of duplicate counting or omissions that would follow from allowing the enumeration to run too long. The first four decennial censuses all used an early August date as the reference, since the summer and fall months were judged to be the best time to find people in what was still an agricultural society. For 1830, “Congress also moved the date of the census ahead two months, to June 1 instead of August [7] as in 1820, on President Adams’s suggestion that this would permit a longer stretch of good weather for the house-to-house enumeration” (Cohen, 2000:121). June 1 remained the census date for the 1840 through 1900 censuses. As the census became more routinized and professional, officials worked to shorten the time of the count and shift the census date earlier in the year. The increasing urbanization of the United States prompted the shift from June 1 to April 15 in the 1910 census; June was “unsatisfactory…because some city dwellers were already out of town for summer vacations, and farmers did not remember enough about the previous year’s crop for the agricultural census” (Anderson, 1988:44). The Census Bureau tried moving Census Day back further still in the 1920 census, to January 1, “at the request of the Department of Agriculture, and also because it was contended that more people would be found at their usual place of abode in January than in April” (Steuart, 1921:571). However, this change “ran into trouble because the winter weather impeded the enumeration and rural leaders complained that many people were working in the city community and hence were not properly counted” (Anderson, 1988:45). After the 1920 experience, census officials were “convinced…that a more nearly perfect and a more rapid count of the people can be made in April than in January.” However—presaging the continuing problem of counting seasonal residents—they acknowledged that this represented a tradeoff (Steuart, 1921:572): It is true that during April and June, when the enumeration has heretofore been in progress, large numbers have been at summer resorts. But at [the January 1920] enumeration it was found that surprisingly high numbers were at winter resorts. Thousands who have their usual places of residence in the northern states spend the winter months in California, Florida, and other southern states. Some of them live in the south several months of each year, and it was difficult to determine their usual places of abode. In this respect the change complicated the work; certainly it did not simplify it. Hence, the 1930 census set April 1 as Census Day, and that date has since been written into Title 13 of the U.S. Code for subsequent censuses. One exception in the 2000 and other recent censuses is the enumeration of remote villages in Alaska, which are rendered unreachable by weather conditions in March and April. In 1930, the count there only began in October; recent censuses have tallied those areas in January or February. |

2–B.2

The Changing Role of Residence Rules: From Enumerator Interviews to Self-Response

The earliest decennial censuses were conducted by marshals on horseback; though the federal agency charged with conducting the census varied,

the method of collecting census information by face-to-face interviewing remained the norm well into the 20th century. The fact that the census was administered in person meant that the field enumerators, ultimately, were responsible for explaining and deciding who should be counted on a “usual residence” standard. This role of enumerator as residence adjudicator was emphasized in the 1880 instructions to enumerators:7

The census law furnishes no definition of the phrase, ‘usual place of abode,’ and it is difficult, under the American system of a protracted enumeration, to afford administrative directions which will wholly obviate the danger that some persons will be reported in two places and others not reported at all. Much must be left to the judgment of the enumerator, who can, if he will take the pains, in the great majority of instances satisfy himself as to the propriety of including or not including doubtful cases in his enumeration of any given family.

Arguably, the most significant change in residence rules and their role in the decennial census was brought about by a major paradigm shift in census operations: the switch from an enumerator-conducted census to a mailed-questionnaire, self-administered response model of census data collection. The 1960 census was the first to move significantly toward this model;8 in that year, households were mailed an “Advance Census Report,” which they were asked to fill out but not return by mail. Instead, enumerators visited the household to collect the forms and transcribe the information onto forms more conducive to the optical film reader then used to process census data. If a household did not complete the advance form, the residents were interviewed directly by the enumerator. Subsequently, legislation passed in 1964 (P.L. 88-530) eliminated the requirement that decennial census enumerators personally visit every dwelling place, enabling broader change in census methodology.

|

7 |

The enumerator instructions and forms for censuses dating back to 1850 are very helpfully archived as part of the documentation of the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series in the “Counting the Past” section of http://www.ipums.umn.edu/usa/doc.html [8/1/06]. Gauthier (2002) also comprehensively lists enumerator instructions and census schedules from 1790 to 2000. |

|

8 |

However, the 1960 census was not the first to use the mail in census data collection. The Census Bureau’s procedural history of the 1970 census (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1970) indicates that mail was used in specialized operations as early as 1890, when questionnaires concerning residential finance were mailed to households with a request for mail return (the same was repeated in 1920, and a similar mail-based program on income and finance was used in 1950). Supplemental information on the blind and deaf was requested by mail in 1910, 1920, and 1930, and an “Absent Family Schedule” was used for some follow-up in 1910, 1930, and 1940. Presaging the 1960 approach, an “Advance Schedule of Population” was delivered to households in 1910; farm households also received an advance copy of an agriculture questionnaire administered as part of that census. Prior to implementation of large-scale mailout/mailback in 1970, experiments and tests of the method were conducted in 1948, 1950 (as a census experiment), 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960 (some of the Advance Census Report responses were requested by mail), 1964, and 1965. |

The 1970 census took the mailout-census model a step forward: census questionnaires were mailed to all households in major urbanized areas (which were thought to include about 60 percent of all housing units), and respondents were asked to mail them back to their local census office on Census Day. This mailout/mailback methodology has been expanded and used in the subsequent censuses; by 2000, 82 percent of the population was covered by mail. The balance of the country was enumerated through a mix of approaches including enumerator visits; Box 2-2 lists the nine “type of enumeration areas” used in 2000.

This major change in census data collection techniques dramatically changed the role of residence rules in the census. Prior to the mail-based model, residence rules had been incorporated in the instructions to census enumerators. The Census Bureau’s task in administering residence rules was relatively small: only enumerators had to be trained in the rules, and enumerators could answer questions from respondents, to the best of their ability, during the census interview. But mail-based methods changed the nature of the exercise: the Census Bureau could develop its own interpretation of “usual residence,” but it now had to try to get every census respondent to grasp the Bureau’s definition based only on information included in the census questionnaire.9 Because only so much information can be included on a single piece of paper, the application of residence rules became trickier—trying to find the right combination of words and cues to induce respondents to make their concept of “usual residence” square with the Bureau’s. (We discuss the evolution of the mail-based census instruments in Chapter 6, illustrating the approaches used in the 1960–1990 censuses in Figures 6-1–6-4.)

2–B.3

Assessment of the 2000 Census Residence Rules

By 2000, the Census Bureau’s internal list of residence rules grew to 31 specific rules, plus a related statement on the meaning of time cycles (e.g., daily, weekly, or monthly) in determining usual residence. This set of rules is reprinted in Appendix A.

The first impression that comes from reviewing the 2000 census residence rules is that they are not organized in a way that a general reader can follow; in large part, this is attributable to the internal (not for public consumption) nature of the full residence rules document. Designed for a more general audience, the residence rules might be structured by major group type (e.g., “students” or “military personnel”) or by the approximate population of the group (so that a living situation in which a person is likely to find oneself comes earlier in the list than rare groups). Instead, the organizational structure of the

|

Box 2-2 Types of Enumeration Areas (TEAs), 2000 Census

SOURCE: Adapted from National Research Council (2004c:Box C.2). |

2000 census residence rules is both weak and operational in nature. Its major headings are obscure—“household population,” “group quarters population, [usual home elsewhere (UHE)] allowed,” “group quarters population, UHE not allowed,” “overseas population,” and “do not list population”—and use jargon (e.g., “group quarters” and “do not list”) and acronyms (UHE) that are opaque to a lay audience. Further, major population groups are not addressed coherently. The rules for counting college students are dispersed into rules 5, 6, and 25 (although that group of rules does, helpfully, provide explicit directions to look at the other related rules); newborn babies are mentioned almost as an afterthought in rule 3 and lost in technical detail of counting hospital patients; military personnel are divided across rules 4, 13, 26, and 27.

As we discuss further in Chapter 6, census residence rules serve several different purposes, and would thus be better handled by crafting different products to fill those various purposes. The 2000 census residence rules document takes an omnibus approach and tries to satisfy all the needs. By straining too hard to be an operational blueprint (e.g., categorizing by “household” versus “group quarters” operations, complete with specific group quarter code numbers in rules 13–19), the document becomes less effective in its primary purpose of clarifying the meaning of “usual residence.”

Finding 2.1: As developed and used in the 2000 census, the residence rules for the decennial census were too complicated and difficult to communicate. The set of 31 formal residence rules was not organized for ease in comprehension, and instead seemed to be a loose amalgamation of previously encountered problematic residence situations. The sheer number and redundancy of the rules detract from their effectiveness in training temporary census enumerators.

2–C

WHY IS MEASURING RESIDENCE DIFFICULT FOR THE CENSUS BUREAU?

In this and the next section we discuss some of the difficulties associated with measuring residence, and “usual residence” in particular, from two basic viewpoints. In this section we focus on the challenges faced by the Census Bureau in specifying what it means by residence; in Section 2–D, we consider the difficulties faced by respondents in answering residence questions.

2–C.1

Definitional Challenges

An inherent problem with the Census Bureau’s “usual residence” approach—particularly when the primary mode of data collection is self-response by individual persons—is that it requires respondents to interpret

and apply “usual residence” as the Bureau does. Yet “usual residence” is not everyday parlance for most people; respondents instinctively need to reconcile complex and technical terms into concepts more familiar to them.

“Residence,” “abode,” “home,” “domicile,” “household,” “lodging,” “dwelling”—even the basic semantics of describing living situations to census respondents present difficulties because these words have different connotations. For instance, the overtones of “domicile” strongly suggest emphasis on a legal address; “home” suggests the presence of family and could also connote a place of origin or birth; “lodging” suggests temporary or current location. At the most mechanical level, “address” is arguably the best word to describe the entity with which the Census Bureau would like respondents to associate themselves—a geographic reference that can readily be located in a particular area. But that word, too, is problematic, given its near-automatic association with “mailing address” and mail delivery; one usually does not think of a post office box as a place of residence, but it would be the natural “address” to report in rural areas without household mail delivery.

The term the Census Bureau uses as its basic unit of measurement is the “household”; operationally, the Bureau draws distinctions between the household population and the “group quarters” (e.g., prisons, dormitories, and hospitals; see Box 2-3) and “service-based” populations (e.g., shelters and soup kitchens). Like the other possible terms, “household” can be a difficult concept to grasp: the word can be “associated with a physical structure, a co-resident social group, a consumption unit, and a kinship group, usually thought to be the family” (Hainer, 1994:337).

The definition and implementation of the basic unit of measurement in the census has varied over time. The 1850 census—seminal in many respects regarding the topic of residence because it was the first to provide detailed enumerator instructions—attempted a sharp delineation. The grouping of people the 1850 census was concerned with was the “family”—and actual kinship had nothing to do with the definition. “A widow living alone and separately providing for herself, or 200 individuals living together and provided for by a common head,” or the “resident inmates of a hotel, jail,…or other similar institution”—these cases “should each be numbered as one family” (Gauthier, 2002:9).10 The 1860 enumerator instructions used similar examples to define “family,” concluding (Gauthier, 2002:14):

Under whatever circumstances, and in whatever numbers, people live together under one roof, and are provided for at a common table, there is a family in the meaning of the law.11

|

Box 2-3 Group Quarters Categories for the 2000 Census

In the parlance used in the 2000 census, one or more group quarters make up a special place: special places are administrative units, while group quarters are the actual living and sleeping facilities. For instance, a university would be considered a special place; its individual dormitories are each group quarters. SOURCE: Jonas (2003). |

Over time, the concept of a “dwelling-house” (1900) evolved into the contemporary terms “household” (1940) and “housing unit” (1960)12 in census instructions. These housing units would be defined by the presence of some factors, including separate front doors (1900), two or more rooms (1950), and kitchen facilities (1950–1970). Similarly, “households” came to be distinguished from what would be called “group quarters” by set characteristics or counts—for instance, the threshold of 5 (1950–1970) or 10 (1980–1990) unrelated persons living together being a “group quarters” rather than a “household.” The 2000 census moved away from a size criterion to differentiate housing units from group quarters; as we discuss further in Chapter 7, the sharp operational distinction between the two concepts raised problems because the Bureau’s housing unit and group quarters listings were maintained separately.

Defining the unit of measurement is difficult in itself; defining “usual residence” at that unit is harder still. In the absence of a universally clear and applicable word to describe what is meant by “usual residence,” another approach is to try to find the actions and activities that respondents are most likely to associate with what the Census Bureau deems to be the “usual residence.” This is the approach taken in most recent censuses, trying to find the bundle of activities—“living and sleeping”? “living and staying”? “eating”?—that most people would identify as corresponding to their usual residence. The 1960 and 1970 censuses, with their explicit definitions of housing units as containing kitchen facilities, clearly put stock in “eating” as being a usual residence activity. Earlier, the enumerator instructions for the 1890 census bluntly sided with “sleeping” as the defining activity (Gauthier, 2002:26):

A person’s home is where he sleeps. There are many people who lodge in one place and board in another. All such persons should be returned as members of that family with which they lodge.13

Instructions in 1950 were equally blunt: “as a rule [the place of usual residence] will be the place where the person usually sleeps.” Respondent sensitivity to these particular key words has been the focus of cognitive testing by the Census Bureau, including those conducted as part of the 1993 Living Situation Survey (we discuss the Living Situation Survey in Chapter 5 and cognitive tests in Chapter 8).

An additional complication in specifying a standard for “usual residence” is that the word “usual” demands reference to a period in time, in ways that are not always easy to determine:

-

“Usual,” relative to how long a time period? Is there some minimum amount of time necessary to establish a place as a “usual” residence? If so, specifying too fine or too coarse a time reference period when asking about residence could yield different answers.

-

Retrospective or prospective? There is also a basic question of whether the time frame should be retrospective (e.g., where a person lived during the 12 months prior to Census Day), prospective (e.g., where a person intends to live for the next 3 months), or centered (an interval around Census Day). A person who has just completed a lengthy business trip or vacation could potentially be tripped up if asked to consider the place where they lived and slept most often during the past week, while asking a person who has moved to a new residence in the past few months where they lived and slept most often during the previous year is problematic.

-

How much weight to put on “intent”? A key factor in distinguishing between a “usual” and a “current” residence location is intent—intent to eventually return to a place even though one is temporarily somewhere else, or intent to remain at a place even though one may have just moved in. Left ambiguous are questions of how highly intent should be considered in determining a usual residence: Can “temporary absences” be so long that they break the tie to a usual residence (such as a 2- or 30-year prison term, a displacement of indeterminate length due to a natural disaster, or near-continuous long-haul truck driving)?

Though the formal residence rules of the 2000 census included an attachment that tried to outline weekly, monthly, and annual time “cycles,” the 2000 census form and some of its predecessors have taken the approach of leaving the time frame decision to the respondent. Respondents are asked to consider where they live “most of the time,” allowing flexibility in interpretation.

2–C.2

Discrepant Standards

Etymology and syntax aside, determining “usual residence” can be difficult because the general concept of residence can be approached through any number of standards, some of which conflict directly with each other and some of which clash with residence standards encountered by people in everyday life. The residence requirements for voter registration in state and local elections may differ from those that federal, state, and local tax authorities use. Likewise, residence for purposes of qualifying for in-state tuition at state colleges and universities can vary substantially from those required to obtain a driver’s license or identification card.

Box 2-4 describes the range of residence definitions and standards that are used in these kinds of everyday applications in the state of California; other

states could be used to illustrate the same kind of diversity. Although none of the applications defines residence in exactly the same way, the definitions do connect in limited ways: for instance, the motor vehicle code cites payment of resident tuition at a California college or voting in a state election as a means of qualifying as a resident for obtaining a driver’s license.

Residence for purposes of registering to vote in elections is a particularly important application in the U.S. system. At the federal level, the 1970 amendments to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibited states from imposing duration requirements of longer than 30 days for eligibility to vote in presidential elections. Individual states vary in their residence guidelines for general state and local elections; as illustrated in the California example, states typically invoke a type of de jure standard (“fixed,” “permanent,” or “usual” residence), though an explicit time period is often stated. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1972 ruling in Dunn v. Blumstein (405 U.S. 330) struck down long-term residence requirements for general state and local elections as discriminatory; the standard in question in the case was Tennessee’s requirement of 1 year residence in the state and 3 months in the county. The court suggested that residence in the state 30 days before an election was a more appropriate benchmark.14 The 1993 enactment of the National Voter Registration Act (better known as the “Motor Voter” Act) requires states to offer opportunities for voter registration in conjunction with applying for or renewing driver’s licenses or other identification cards. The act links the processes of voter registration and driver certification, even though the residence qualifications for both purposes may differ in state law or regulation.

Enduring Ties

As discussed above, residence can also be seen as an act of belonging. The adage “home is where the heart is” rings true for many; people may consider their family home to be their real home or “usual residence,” even if that location is not what a strict majority-of-nights-stayed or other measure might suggest. Family and kinship ties may be important in determining where people say that they usually live; so too may be the presence of friends or affiliation in community organizations.

The notion of “usual residence” as being defined by feelings of connectedness to a place, for any number of reasons, may usefully be called an “enduring ties” standard. The standard takes its name from the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Franklin v. Massachusetts (505 U.S. 788, 1992); in that case, the majority opinion commented that usual residence “has been used broadly enough to include some element of allegiance or enduring tie to a place.” Franklin v.

|

Box 2-4 State Definitions of Residence: California Residence for In-State College Tuition: With slight variations, the campuses of the University of California, California State University, and California Community College systems define residency consistent with “Uniform Student Residency Requirements” (California Education Code, Part 41 and §68062). These requirements hold that:

(In particular, minors under the age of 18 who may be attending college are considered by the state definitions to be resident at their parental home.) Consistent with these guidelines, the state colleges and universities generally require that residence be demonstrated by all three of the following criteria:

Links to the individual UC campuses’ interpretation of residence can be found at http: //www.universityofcalifornia.edu/admissions/undergrad_adm/ca_residency.html [6/1/06]. |

|

Residence for Voting Purposes: California election law defines a person’s residence for voting purposes as their “domicile:” “that place in which his or her habitation is fixed, wherein the person has the intention of remaining, and to which, whenever he or she is absent, the person has the intention of returning” (California Elections Code, §349). Generally, the section defines a person’s residence as “that place in which the person’s habitation is fixed for some period of time, but wherein he or she does not have the intention of remaining.” Hence, at a given time, a person may have more than one “residence” but only one “domicile.” Domicile status in California is voided with a move to another state, with the intention of either “making it his or her domicile” (§2022) or “remaining there for an indefinite time…notwithstanding that he or she intends to return at some future time” (§2023). However, “a person does not gain or lose a domicile solely by reason of his or her presence or absence from a place” while in military service, “nor in navigation, nor while a student of any institution of learning, nor while kept in an almshouse, asylum or prison” (§2025). “If a person has a family fixed in one place, and he or she does business in another, the former is his or her place of domicile,” unless the person intends to remain at the business location (§2028). Further, “the domicile of one spouse shall not be presumed to be that of the other, but shall be determined independently” (§2029). Residence for Taxation Purposes: The Franchise Tax Board’s “Guidelines for Determining Resident Status—2004” (FTB Publication 1031) indicates that California tax law follows a pragmatic definition of resident: someone who is “in California for other than a temporary or transitory purpose” or who is “domiciled in California, but outside California for a temporary or transitory purpose.” However, in asking taxpayers to classify their own residency, the tax standards invoke enduring ties. “The underlying theory of residency is that you are a resident of the place where you have the closest connections,” says the board. The publication lists several factors that can determine residency:

“In using these factors, it is the strength of your ties, not just the number of ties, that determines your residency.” [As a more concrete suggestion, the document notes that “you will be presumed to be a California resident for any tax year in which you spend more than nine months in this state.”] Residence for Obtaining a Driver’s License: The California Department of Motor Vehicles (http://www.dmv.ca.gov/dl/dl_info.htm) advises that “residency is established by voting in a California election, paying resident tuition, filing for a homeowner’s property tax exemption, or any other privilege or benefit not ordinarily extended to nonresidents.” |

Massachusetts is described in more detail in Box 2-5; we will discuss the case further in Sections 3–F and 3–D.1.

Box 2-4 provides a thorough example of an “enduring ties” standard in the suggested definition of residence used in California for purposes of taxation.

Residence in Administrative Records

Thus far, we have focused on the Census Bureau’s basic problems in defining a residence concept so that it can be used to try to elicit accurate information from census respondents. However, a potential mismatch in residence standards arises in situations when the Bureau has to blend data gathered directly from respondents (or through enumerator follow-up interviews with respondents) with data from administrative records. As we discuss below (in Chapter 7 and Table 7-1), roughly half of the data collected on group quarters residents in the 2000 census was obtained through use of administrative records maintained by facilities where personal interviewing or questionnaire distribution was not feasible or not permitted. Thus, the quality of residence information and the definition under which it is collected could vary greatly: prisons might have records of inmates’ sentencing jurisdiction but not detailed information on preincarceration or family addresses, and records available for military personnel might list a deployment location or a home base or port but not detailed address information.

In terms of final counts, discrepancies in administrative records’ residence standards were likely not a major problem in the 2000 census. Only a few group quarters types were eligible for “usual home elsewhere” reporting—that is, the respondent could indicate that they did not usually live in the group quarters facility and could instead identify the address which they considered their usual residence. The highest-frequency group quarters types—college housing, prisons, and health care facilities—were not eligible for this reporting; regardless of what residence information might be coded in administrative records, people at those facilities were counted at the facility location.

2–C.3

Changing Norms and Living Situations

From the Census Bureau’s perspective as data collector, residence information can be difficult to obtain accurately simply because of the demographic and social diversity of the American population. Over the course of the past few decades, living situations have taken different and more fluid forms. For instance, greater rates of cohabitation of couples—living together, but unmarried—and increased cultural acceptance of cohabitation arrangements challenge traditional definitions of family and, with it, “usual” residence. The prevalence of divorce and joint physical custody arrangements for children of divorced couples creates conundrums in identifying a single place as a child’s

|

Box 2-5 Franklin v. Massachusetts (1992) One of several legal challenges to arise from the 1990 census, the case eventually decided as Franklin v. Massachusetts (505 U.S. 788), targeted the Census Bureau’s procedure of allocating overseas employees of the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) to individual states for purposes of apportionment. The commonwealth of Massachusetts, and two of its registered voters, brought the suit, arguing that this allocation may have deprived Massachusetts of a congressional seat that was ultimately awarded to the state of Washington. The district court sided with Massachusetts, directing the Secretary of Commerce to remove the overseas employees from apportionment counts. In July 1989, then-commerce secretary Robert Mosbacher decided to allocate overseas federal employees to their home states, citing growing sentiment in Congress (as evidenced by a number of introduced, but not passed, bills) in favor of their inclusion. Moreover, the Mosbacher decision was buoyed by DoD’s announced plans to poll its employees to determine “which State they considered their permanent home” (505 U.S. 788, §I). Ultimately, though, DoD scrapped the proposed survey, and still later DoD was unable to provide data on employees’ last 6 months of residence within the United States. Instead, the Census Bureau allocated DoD employees by the “home of record” indicated in their personnel files. Sections I and II of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s opinion for a 5–4 court majority focused on the legal underpinnings of Massachusetts’ claim that the decision of the president and the commerce secretary to include overseas federal employees was inconsistent with the Administrative Protection Act. Section III of the O’Connor opinion spoke to Massachusetts’ standing to bring the case on constitutional grounds, and was only joined by three other justices; opinions filed by Justices John Paul Stevens and Antonin Scalia explained disagreements, in part or in whole, with the O’Connor opinion’s conclusions on the constitutional standing arguments. Section IV of the O’Connor opinion, on the merits of a constitutional challenge, is the most relevant to discussion of census residence issues, and was joined by eight justices (with only Justice Scalia, having concluded that Massachusetts lacked standing, declining to join an argument on the merits). Referring to the Act of March 1, 1790, O’Connor wrote that “‘usual residence’ was the gloss given the constitutional phrase ‘in each State’ by the first enumeration Act and has been used by the Census Bureau ever since to allocate persons to their home states. … The term can mean more than mere physical presence, and has been used broadly enough to include some element of allegiance or enduring tie to a place.” The opinion further noted cases in which “usual residence” had been broadly defined, such as the pre-1950 placement of college students in the state of their parents’ residence. The opinion concluded that Mosbacher’s decision was “consonant with, though not dictated by, the text and history of the Constitution, that many federal employees temporarily stationed overseas had retained their ties to the States and could and should be counted toward their States’ representation in Congress.” Indeed, the allocation to the employees’ home states “actually promotes equality [of representation],” assuming that the employees have legitimately retained ties to their home states. Thus concluding that the Massachusetts case failed on its merits, the district court judgment was reversed and the Bureau’s inclusion of overseas federal employees in apportionment totals was upheld. |

“usual” residence; joint custody arrangements also heighten the potential for duplication of census records for children, in cases where neither parent (often without any discussion in the matter) cedes a child’s “usual” residence to their ex-partner. Shifting economic tides and general public attitudes affect immigration patterns and the tendency for foreign workers to migrate from place to place to work, further complicating the meaning of usual residence.

The past several decades have also seen changes of technology that can reduce a person’s physical tie to one “usual residence.” Of course, ongoing development of transportation systems make it easier for people to be more mobile; recreational vehicles make it possible for people to literally live on the road for weeks or months at a stretch, and air travel makes it possible for employers to deploy staff across the nation (or around the world) for extended periods. More significantly, cellular phones and e-mail truly untether people from a single physical address.

Other broader social and demographic trends that complicate the definition of residence are more subtle and technical, but affect major groups of interest. In particular, across many fields, the very notion of what the Census Bureau has come to identify as “group quarters” has been upended. Medical advances that promote longevity, coupled with the changing economics of health care, have led to a diversity of health care services that do not square with traditional notions of “hospitals” and “nursing homes,” among them the increased number of assisted living options and the presence of semiresidential long-term care options in some hospital wards. To attract student interest, some colleges and universities have modified their campus housing stock, providing more complete apartment-style living communities that are virtually indistinguishable from regular (nonuniversity) households.

2–C.4

Inherent Tie to Geography

On a practical level, residence can also be a difficult issue for the Census Bureau because residence is inextricably linked to geography. A perfect set of residence rules, which could flawlessly guide respondents through the process of identifying themselves at the place the Census Bureau considers the person’s “usual residence,” is ultimately futile if the Bureau’s geographic resources are not in order.

Inclusion on the Bureau’s MAF is central to inclusion in the census; the MAF is the source of mailing addresses for the mass mailout of questionnaires to most of the country and is the basis for follow-up with nonresponding households. Just as social and demographic trends affect respondents’ notion of usual residence, so, too, can they affect the ability to put together and maintain a comprehensive address list. We have already mentioned the increasing blurriness between what has typically been dubbed a “group quarters” location and the general household population. Other examples include

the dense concentration of new immigrants in unconventional housing stock in urban centers (making it difficult to maintain a complete housing inventory and to define what constitutes a housing unit), the changing nature of migrant workers camps in the agriculture industry, the use of subletting and renting of finished basements and attics of houses to nonfamily members (who might not be thought of as belonging to the “household”), and the rapid pace of new construction in large suburban and exurban subdivisions and areas. Finally, even if an address is known on the MAF, it still needs to be accurately geocoded (that is, linked to a fixed geographic location, such as latitude and longitude coordinates) for accurate tabulation. Gaps and inaccuracies in the Census Bureau’s geographic reference database, the Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing (TIGER) system, can lead—and did lead, in 2000—to geocoding failures and, possibly, exclusion from the census or gross geographic misallocation.

In advance of the 2010 census, the Census Bureau has embarked on its MAF/TIGER Enhancements Program in order to modernize its geographic resources; we discuss this effort, and the role of the MAF and TIGER, in Section 8–A.

2–D

WHY IS DEFINING RESIDENCE DIFFICULT FOR RESPONDENTS?

There are several reasons that respondents themselves can find it difficult to follow residence rules and, in some cases, to resist them entirely. First, respondents have their own notions of what constitutes residence; these are often consistent with the Census Bureau’s rules, but not always. Gerber (2004) summarizes some basic factors that can shape a respondent’s concept of residence:

-

Social ties: People without close ties may not naturally be included in a person’s accounting of who “lives” at their home; a houseguest who stays for an extended period of time who legitimately has no other place to stay may not be dubbed a resident by a census respondent, even though they would be considered residents under Census Bureau rules.

-

Kinship and economic contribution: Family membership can be critical to some respondents’ concept of residence: the person renting a finished room in a basement or attic is not family, and thus may not be tallied as a resident. Conversely, the strength of economic ties may be essential to some people: if an extended family member is staying in the house for some time, between jobs or residences, but is not being charged rent, the lack of economic contribution may trigger some respondents to exclude them from the count.

-

Discounting “just for work” living situations: People may discount residences that are arranged just to facilitate work. Examples include an apartment close to work that a person uses during the week rather than the family home he or she returns to on the weekend, the long-term lodging used when a person is stationed for work at another site for several weeks or months, or rooms for live-in employees. The same reasoning may apply to college students and their “just for school” residences.

-

Varying legal standards: As described in the previous section, residence is defined in myriad ways in state and local law; people encounter these definitions in their day-to-day lives and may be confused as to what exactly constitutes residence in a particular context.

Second, respondents’ concepts of “household” may vary, which in turn can alter their notion of who lives in their “household.” Hainer (1994:337) argues that the traditional Census Bureau interpretation of “household” as a “discrete monothetic unit useful for description and comparison, and one that is presumed to be universally appropriate for the accurate counting of all populations,” is flawed. Rather, “household” living arrangements can be very fluid—unrelated persons living together in groups, extended family members moving in and out, and so forth. In short, “household is a polythetic category” and its definition can vary sharply “between various social groups and within them.”

Third, the instinctive desire to preserve the family unit runs counter to the Census Bureau’s “usual residence” principle in several major cases, and can lead to noncompliance with residence rules. Prominent among these cases is the situation of children at college; regardless of how clear instructions may be, or how logical a “usual residence” ruling that college students be counted at school may be, some parents will undoubtedly consider it anathema to count their children at any location other than the family home. Likewise, a spouse in a nursing home or long-term hospital stay may instinctively be considered part of the household, even if his or her “usual residence” is at the facility, and families with members serving in the military may include those absent service members in their household count.

In some part, the notion of preserving family structure in the census may arise from the emerging role of the census as a social research tool rather than being viewed strictly as a head count. Specifically, the popularity of genealogical searches using census records—released 72 years after the census, as was done most recently for the 1930 census—to trace family ties may in some way lead people to expect that future generations may use modern census data in the same way.

Fourth, as we discuss further in Chapter 6, some respondents will not follow residence instructions because they are likely to ignore instructions, generally. Some people will reason that they already know how to fill out a

form and decide that they do not need to look at the instructions. Particularly if instructions appear long and complex, they may determine that they can figure out the questions on their own—and on their own terms.

Even for respondents who do read the instructions, there is limited space on the form to provide residence information and instructions, and not all concepts can be adequately explained in that space. If there is an easy mechanism for respondents to obtain help on the question through other means (e.g., looking at a Web site or calling a help center), some may take advantage of those options. But most will not: if the provided instructions do not address their own situation, they will answer as best they can—which may not be strictly correct, by the Census Bureau standards.

2–E

CONSEQUENCES OF RESIDENCE COMPLEXITIES

The basic consequence of difficulties with census residence rules—either in their definition or in their interpretation by census respondents—is spotty census coverage. That is, some people will be omitted from the census entirely, while others will be counted multiple times. Others may be counted only once, but in the wrong place.

2–E.1

Omission and Duplication

Since the 1940s the Census Bureau has published evaluations of the census, showing that the census has undercounted several groups. Though census coverage was always of academic interest, undercount or overcount in the census was not perceived as a major political issue until the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1962 ruling in Baker v. Carr reinforced the “one person, one vote” principle. In the altered political landscape that followed, with its increased attention to strict mathematical equality in legislative districts and judicial invalidation of districting plans with even tiny amounts of variability, the “exactness” of the census count became ever more important and contentious.

Planning for the 1980 and 1990 censuses featured lengthy debates over the prospective undercount of certain groups, particularly in urban areas and among minority groups.15 Anticipating undercount and other coverage problems in 2000, the Census Bureau put in place an Accuracy and Coverage Evaluation (A.C.E.) Program. However, the A.C.E. analysis ultimately spotlighted an unexpected problem: compared with a separate analysis using demographic analysis, the A.C.E. suggested an overall census overcount driven by an esti-

mated 5.2 million duplicate persons in the census.16 The estimates of net undercount and overcount in the 2000 census are described further in Box 2-6.

Duplication in the census has always had a certain “advantage” over census omission in that it is easier to grasp and conceptualize; at least in theory, data can be reanalyzed and cross-checked to try to identify duplicate records. Until 2000, though, census data capture lacked critical information to make such a records check possible: the 2000 census was the first to use optical character recognition to capture and store the names of persons on census records. This advance permitted A.C.E. researchers to perform matches by name and date of birth. This was first done in the Further Study of Person Duplication conducted as part of the Census Bureau’s Executive Steering Committee on A.C.E. Policy research program on the possible statistical adjustment of 2000 census totals; in its first stages, the A.C.E. follow-up survey was matched by name and date of birth against the census to try to find duplicate records (Mule, 2002). Later, as the method was refined, the complete set of census records was matched against itself, using a model based on name, geographic distance, age group, and status as a housing unit or group quarters to estimate the probability of duplication (Fay, 2004).17 The success of the methodology has raised the strong prospect of real-time unduplication procedures in the 2010 census—an ongoing set of internal matches as census returns are being received and processed that could spotlight potential duplicates and help census administrators send enumerators to those households to try to obtain the correct information.

The Fay (2004) analysis of the full census-to-census person match suggests empirical results that are consistent with prior impressions of the nature of duplication. Age distributions of estimated duplication rates suggest relatively high levels of duplication among children around 10 years of age (possibly suggestive of children in joint custody situations). Young women in their early to mid-20s, and to a lesser extent men in the same age range, also show elevated duplication rates, “possibly associated with forming new households while being reported by a previous one” or with double counting of college students (Fay, 2004:2). Focusing on those cases where duplicates

|

16 |

As we discuss in more detail in Chapter 8, duplicate housing units can occur as well as duplicate persons. Indeed, the first indication that duplication would be a major story of the 2000 census came as the 2000 census was in progress; a comparison with the count of housing unit addresses on the MAF with another estimate of the size of the housing stock suggested a potentially large duplication problem. The Census Bureau mounted a special ad hoc unduplication program in summer 2000; based on that operation, 2.4 million housing units (comprised of 6 million people) were flagged as potential duplicates. After review, 1 million housing units (2.4 million people) were included in the census but the others were permanently deleted (National Research Council, 2004c:137–138). |

|

17 |

Fay (2004:1) notes that the models take into account “the frequency of the name in the geographic area in question. In practice, the models indicate that exact matches on name and date of birth are almost always true duplicates if they occur in the same county, but the models have an important effect in estimating the number of between-county and between-state duplicates.” |

|

Box 2-6 Undercount and Overcount in the 2000 Census Prior to the April 2001 deadline for delivery of redistricting data, the Census Bureau’s Executive Steering Committee for A.C.E. Policy (ESCAP) weighed a set of highly discrepant results. Relative to the census count of 281.4 million, estimates derived using the A.C.E. suggested a 1.18 percent net undercount at the national level (an improvement from the estimated 1.61 percent net undercount in the 1990 census). Moreover, the A.C.E. estimates suggested a reduction in net undercount among the black and Hispanic populations, from 4.57 percent and 4.99 percent in 1990 to 2.17 and 2.85 percent in 2000, respectively. However, results from demographic analysis (DA)—essentially, adding estimates of births and immigrants to the previous census count and subtracting estimated deaths and emigrants—told a different story. The hard-to-estimate size of the illegal immigrant population is important to a DA count; depending on which estimate was used for this subgroup, DA suggested either a much smaller national net undercount (0.32 percent) or an unexpected net overcount (−0.65 percent). In light of these discrepancies, ESCAP concluded that there might be a significant flaw in the A.C.E. methodology; it directed a program of further research and recommended that the census data not be adjusted, a recommendation later approved by the commerce secretary. Further refinement of the A.C.E. methodology was conducted during summer 2001, in advance of an October decision on whether adjusted census data should be used as the basis for census totals used for such purposes as fund allocation. The new studies suggested that use of the A.C.E. to adjust census results would overstate the population because the census itself had more errors of erroneous enumeration (overcount) than originally indicated. A careful evalution follow-up study, combined with methods for detecting duplicates by matching by name and date of birth (discussed further in Box 8-1), found an estimated 2.9 million erroneous enumerations that were not discovered in the original A.C.E. Bureau analysts and a National Research Council (2004c:180) panel conjectured that problems in defining census residence might explain many of these duplicates: cases seemed to include college students double-counted at their parental homes and at school, children in joint custody counted at the homes of both parents, and seasonal residents with more than one house. The Bureau once again recommended against statistical adjustment of the 2000 census data for fund allocation and other purposes. For a third and final time, the Bureau recommended against adjustment in March 2003; this time, the decision involved whether adjusted census data would be used as the basis for postcensal population estimates. Between October 2001 and March 2003, Census Bureau staff engaged in a further major set of evaluation studies, producing a final set of results dubbed A.C.E. Revision II; these results indicated a 0.5 percent net overcount of the population. Final DA results suggested a very small, 0.1 percent net undercount. SOURCE: National Research Council (2004c:Tables 5.1, 5.2). |

appear to exist between persons counted in both a group quarters and a regular housing unit, sharp duplication rate peaks occur in the college-age population and for people starting around age 70, suggesting the importance of college students and hospital and nursing home patients as potential sources of duplication. Analyses of the 1990 and 2000 censuses, as well as their predecessors, suggest that census omissions—the undercount—are heavily concen-

trated among young black males, children under 10, people living in homes where they are unrelated to others, movers, and those who rent rather than own their homes (National Research Council, 2004c).

Census residence rules that are clearly conveyed are a key part of a strategy to combat person duplication; given the prominence of groups like college students and nursing home patients as potential census duplicates, a more effective way of ensuring that these groups are counted at one place is certainly needed. But residence rules alone can not solve the entire problem of census omission and unduplication. As was also learned in 2000, even census programs designed to counter census errors can sometimes serve to exacerbate them. For example, the coverage edit follow-up (CEFU) operation both added and subtracted people from the census. This telephone follow-up operation was intended to collect data on people in large households (those that indicated more than 6 people living there, even though the census form only allowed for collection of data on 6 residents) and to resolve count discrepancies between the reported household population count and the actual number of data-defined18 people recorded on the census form. The operation was applied to all mail returns, including both census short and long forms, as well as certain Be Counted19 forms and Internet data collection responses processed before June 8, 2000. About half of all CEFU cases were not completed for various reasons, including the lack of a telephone number, but some decision had to be made on the household size for all of them. Since 6.5 percent of the cases that were completed were found to be duplicates, the failure to complete CEFU for all cases (sticking with the original determined count) undoubtedly added some people to the count who were duplicates (Sheppard, 2003).

As our predecessor census panels have noted (National Research Council, 2004c:Finding 1.10), the Census Bureau’s coverage evaluation research based on the 2000 A.C.E. is insightful and of high quality, and the subsequent work that has been done on the complete matching of census records against themselves is similarly commendable. Although the work has yielded some better glimpse at the nature of duplication in the census, it does not speak as strongly to the nature of census omission. As the next census draws near and becomes the Census Bureau’s overriding operational goal, it can be difficult to devote resources to continuing to mine the data from the previous census. However, we believe that a continuous process of developing hypotheses from those data and using those lessons for future census planning is absolutely essential.

In that spirit, we suggest that evaluation of the 2000 census not be considered to be a completed process.

Finding 2.2: Although the research done to date does provide some information on the nature of omissions and duplicates in the 2000 census, the analyses are not sufficient to fully sort out important effects, and the data that have been collected need further analysis.

We note that the person-matching routines face a significant data limitation, which is the lack of coded information on “any residence elsewhere” reported by census respondents. Combining name and date of birth is certainly better than matching on name alone, but very common names (e.g., “Bob Smith”) will still create matching difficulties. Information on “any residence elsewhere” could augment search capabilities by refining the geographic scope. We discuss this point further in Section 8–B.

2–E.2

Group Quarters Enumeration

The group quarters population is a particularly challenging one for census residence rules. Difficult as the concept may be to work with, though, it is important to keep the general nature of group quarters data collection in mind when thinking of the consequence of definitional and operational aspects of census residence rules. It is important for census residence concepts to deal with group quarters as accurately as possible because the decennial census has historically been the only comprehensive data source on characteristics of the group quarters population. Regardless of its flaws, the decennial census serves as the best—and sometimes the only—window on this small (2.7 percent) but significant part of the population.

The Census Bureau’s fiscal 2006 budget request included funds that would add group quarters into data collection for the American Community Survey (ACS). The quality of group quarters data collection is uncertain—whether improved group quarters definitions and more highly skilled ACS interviewers will be able to offset the disturbingly high missing data rate (and, correspondingly, the rate with which those missing data had to be imputed) for many census long-form data items in 2000 (National Research Council, 2004c). Other federal and private surveys probe parts of the group quarters problem, but the decennial census remains unique in its comprehensive nature. As in previous years, the 2010 census will be examined as a source of benchmark data on the size, growth, and nature of the population living in prisons, college dormitories, nursing homes, and other group quarters.20

|

20 |

That said, the ability to measure change from the previous census may be affected by changes to the definitions of group quarters; see Chapter 7. |

2–F

PLANS FOR 2010

2–F.1

One Rule: Proposed Residence Rules Revision

In preparation for the 2010 census, the Census Bureau established an internal working group to refine residence rules and concepts, with the objective of testing revisions in the 2006 census test and the 2008 dress rehearsal, and, ultimately, using them in the 2010 census. This panel’s work is intended in part to review this initial work and provide guidance.

One of the panel’s regular meetings in December 2004 was devoted almost exclusively to a comprehensive walk-through of the residence rules of the 2000 census. Census Bureau staff briefly reviewed historical highlights of each of the 31 formal rules; “straw man” suggestions for changes to the rules were advanced, and the ensuing discussion provided both constructive criticism of the existing rules as well as possible directions for improvement. In particular, the public discussion at that meeting yielded in raw form the basic argument that we underscore and elaborate on in this report—namely, that there is a need for a clearly articulated set of residence principles, and that it is from these principles that other products (including analogues of the current census residence rules) should be developed.

Based on that feedback, the Census Bureau residence rules staff continued work in advance of a March 2005 meeting with the panel. At that meeting, the Census Bureau presented a draft recommendation that replaced the 31 formal rules of 2000 with a single residence rule for 2010; a supporting document, similar to the 2000 census residence rules list, described how this single residence rule should be applied in a variety of living situations. This “one rule” approach and the major proposed differences are summarized in Box 2-7.

To its credit, the Census Bureau has also conducted parallel work on redefining group quarters, with the objectives of creating an integrated address file (rather than a separate MAF and group quarters roster) and of testing revised definitions in 2006 and 2008. We discuss the group quarters redefinition efforts in Section 7–B and Box 7-1.

2–F.2

Assessment

The Census Bureau’s progress to date in revising the census residence rules has been highly commendable. With its draft revision, the Bureau has shown a willingness to make broad changes; we encourage this reconsideration of core census concepts and urge that old conventions be substantially revised, if not fully for 2010 then for future censuses.

In this chapter, we have reviewed the nature of census residence rules and the general issues of residence in the context of the decennial census. The chapters that follow expand our comments and present our recommendations

|

Box 2-7 Census Bureau’s Proposed 2010 Census Residence Rule The 2010 Census Residence Rule The 2010 Census residence rule is used for determining where people should be counted (which means tabulated) in the census. Residence Rule: Count people at their usual residence, which is the place where they live and sleep most of the time. People in certain types of group quarters (GQs) on Census Day should be counted at the GQ. These GQ types are listed in the box below. People who do not have a usual residence or cannot determine a usual residence, and who are not in one of the GQs types listed below, should be counted where they are on Census Day. (As of the Census Bureau’s March 15, 2005, draft, the specific “Group Quarters Where People Are Counted at the Group Quarters” had not yet been determined.) Proposed Changes to Residence Situation Applications The Census Bureau’s proposed “one rule” is accompanied by a listing of how the rule applies to a variety of residence situations. Most of these are adapted from the 2000 census residence rules, with one change and several formal additions:

|

on specific issues, but we first end this chapter with our assessment at the macro level.

First is a basic but surprising fact arising from examining the legal mandates of the census.

Finding 2.3: Though the concept inherits from a long tradition of practice dating to the 1790 census act, active census law and regulation do not define the residence standard for the decennial census (de jure or de facto), nor do they define what constitutes “usual residence.”

To be clear, the panel believes that it is very much for the best that Title 13 is not highly prescriptive of the exact mechanics of the decennial census; the open-endedness gives the Census Bureau much-needed latitude to develop and continue to refine its craft. Nor do we relish or advise a full congressional review and reopening of Title 13. What we do find is that, in contrast with the enabling laws for international censuses (see Appendix B), it is somewhat unusual for core census residence concepts in the United States to be as “hidden” as they have been in the past, deriving from the spirit of a centuries-old statute and kept in full form as a purely internal Census Bureau document. Accordingly, we suggest that census residence rules and concepts be made more transparent. Approaches to promote the transparency of census residence concepts to the public and decision makers could include posting notice of, and inviting comment on, residence standards through promulgation in the Federal Register, as the Bureau does with other basic operational plans. Information on how the Bureau defines residence should also continue to be posted to the agency’s Web site.

The second point of the assessment follows from the first: the base residence standard of the decennial census—whether it is a de jure type or a de facto type—is not explicitly written into law. As a result, an evaluation of census residence rules necessarily prompts some consideration of this fundamental question. Since its inception, the U.S. census has followed a de jure-type model with its “usual residence” standard; we believe that it is important to consider whether a change in the residential standard—to more of a de facto orientation—is warranted. Moreover, it is very appropriate that the choice of residence standard continue to be periodically revisited in ensuing decades.

The choice of a de jure or de facto approach is particularly salient for the U.S. census because of the adoption of the ACS as a replacement for the census long form. While the decennial census follows a “usual residence” standard that can be considered a de jure style, the ACS relies on “current residence”—defined by a “two-month rule”—as its benchmark, establishing it as a de facto type. Having just begun full-scale data collection in 2005, the ACS is still 2 years away from producing a steady stream of estimates for many geographic