–8–

Operations, Research, and Testing

DEVELOPMENT OF RESIDENCE PRINCIPLES as a conceptual base for the census is essential, as is adjusting strategies for eliciting residence and roster information from respondents. However, it is also important to carry those principles over to the design of the specific techniques and methodologies used in fielding the census. It is also true that improvements to census operations and methodologies depend critically on an effective and vigorous program of research and testing. The types of research that we believe are essential to the determination of accurate resident counts—and to census quality, generally—can be roughly partitioned into groups:

-

quantitative, analytical work on diverse living situations to improve understanding of the context of residence in the census;

-

a program of experiments to accompany the 2010 census, to evaluate the efficacy of major changes to residence data collection in 2020 and beyond;

-

improved research on the conduct of relevant census operations, such as group quarters enumeration, address list development, and unduplication methods; and

-

testing and experimentation at an intermediate level—between small-sample cognitive testing and full-scale test censuses—that improves understanding of operational concerns.

We discussed the first of these in Chapter 5 and suggested a major test of a question-based approach collecting residence information (including universal provision for “any residence elsewhere” [ARE] reporting) in Chapter 6.

This chapter focuses on the latter two threads of research, including direct recommendations for improvement of some census operations, and offers comments on the Census Bureau’s research program generally.

8–A

MASTER ADDRESS FILE

The concept of the Master Address File (MAF)—the Census Bureau’s complete inventory of known living quarters and business addresses in the United States—is a surprisingly new one. It was only after the 1990 census that the Census Bureau elected to maintain a continuous address list, rather than scrapping the address list after one census and building it anew prior to the next. As currently implemented, the MAF contains a mailing address for each of the living quarters on the list, if one exists; it also contains an intricate set of logical flags and indicators that denote the operations that added or edited each address.

Finding 8.1: An accurate MAF is crucial to the quality of the decennial census, as well as the Census Bureau’s other major survey programs. Together with the Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing (TIGER) system database, the MAF provides the key linkage between personal census form responses and specific geographic units. Inaccuracy in MAF and TIGER detracts from the quality of the decennial census, producing errors of inclusion and omission.

A full analysis of MAF and its construction is beyond the scope of this panel, but it is germane because residence rules concerns should be reflected in several ways:

-

Scope: Work on MAF should make use of local area expertise in building a full list of residence locations, especially for irregular housing stock such as converted apartments, multi-use buildings, and small multi-unit structures. The work should also address the “seasonality” of housing stock: that is, it would be useful to have some flag or assessment of whether an address is purely a seasonal home (e.g., a time-shared property), a part-time seasonal home (e.g., rented out for part of the year), or a full-time residence.

-

Design: What are the useful flags to include? What new update operations should be done to ensure completeness (e.g., a mechanism for including hotel living quarters)?

-

Evaluation: In what geographic locations, and for what types of housing stock, is error in the MAF most prevalent? A major problem and frustration in 2000 was the lack of an audit trail; because the logical flags on

-

the MAF were not time stamped in any way, it was difficult if not impossible to tell how and when various updating operations touched address records. Such an audit trail is essential for effective evaluation. Consideration should also be given to detailed case history (ethnography) of a sample of addresses.

We endorse the recommendations of previous Committee on National Statistics panels (National Research Council, 2004c,b), and especially the recommendation that a detailed plan for continuous updating of MAF records by state, local, and tribal governments be developed and implemented (National Research Council, 2004b:Rec. 3.1). In particular, the Bureau should continue to find ways to obtain help from local and tribal authorities in obtaining information on unusual housing stock, such as multiple housing units inside family homes and leased hotel or motel quarters.

In Recommendation 6.3 we urge the Bureau to permit respondents to indicate cases where they believe that the census questionnaire reached them in the wrong place. That recommendation serves several important purposes, among them the production of valuable operational data during the conduct of the census (allowing diagnosis of significant addressing problems) and alleviating the frustration of respondents who receive a misaddressed form. However, the recommendation also interacts with the MAF development process in important ways. It is the constant maintenance and updating of MAF that helps to make the recommendation tractable; in principle, fewer gross addressing errors should result from a continually updated MAF, and so processing respondent-corrected information should not overwhelm follow-up resources. But it is also important that the stream of respondent-corrected data not be simply thought of as an operational diagnostic: the real value of respondent-suggested corrections may come from the use of those suggestions to detect and correct errors in the MAF itself. It is reasonable to expect that many of the respondent-suggested changes will be relatively routine, such as questionnaires for individual apartments in large residential buildings being placed in the wrong mailbox. They may also provide clues to larger problems: among these are the renaming of streets, multiple names attached to the same street segment, or the repartitioning and relabeling of individual units in multi-unit structures. We urge that the Census Bureau take advantage of this information, not putting absolute weight on the precoded MAF entries or on the respondent-reported information.

Recommendation 8.1: Pursuant to Recommendation 6.3, respondent-corrected address information should be one source of information to update the MAF.

Relevant to the goal of the unified address list and group quarters roster, participants in the 2010 census local geographic partnership program should

be allowed to review address listings for group quarters in their jurisdictions, not just the household population listings. In addition, the Census Bureau should consider an institutional Local Update of Census Addresses program under which colleges and universities, medical facilities, and other group quarters locations can review the Bureau’s address listings for their facilities.

8–B

UNDUPLICATION METHODOLOGY

The panel’s charge is on how residence rules and related concepts affect both undercount and overcount in the census, as suggested by the titular goal of counting people once (no omissions), only once (no duplicates), and in the right place. A major focus of the coverage evaluation effort following the 2000 census was on duplication in the census, given that Bureau analysts estimated that the census represented a net overcount. Unduplication operations in the 2000 census took several forms and occurred at different stages of the census process, as outlined in Box 8-1.

Emboldened by the 2000 census work on unduplication—capped by the insights gleaned from a complete match of the full set of census records to itself (using a probability model based on name and date of birth) to detect duplicates—current plans for 2010 call for new refinements. In particular, the Bureau is considering something close to “real-time” unduplication in the processing of returns.

Another National Research Council panel is currently studying the emerging coverage evaluation program of the 2010 census, and we have viewed the exact mechanics of unduplication as the province of that panel. However, we briefly offer some suggestions and comments on emerging unduplication methods as relevant to our charge. Both the 1990 Post-Enumeration Survey and the 2000 Accuracy and Coverage Evaluation Program were designed to focus on estimates of net coverage error—aggregate measures of undercount and overcount for particular populations—and not on the individual sources that contribute to that under- or overcoverage. We concur with the Panel to Review the 2000 Census (National Research Council, 2004c:Finding 1.7) that development of methodology for examining the components of gross census error (both omissions and undercounts) is vital, rather than a pure focus on net coverage.

Recommendation 8.2: A comprehensive assessment of the components of gross coverage error (both undercount and overcount) should be added as a regular part of the census evaluation program.

|

Box 8-1 Unduplication in the 2000 Census Aside from precensus editing of the MAF, the only unduplication program explicitly planned to take place as part the conduct of the 2000 census was application of the Census Bureau’s primary selection algorithm (PSA). The census provided multiple chances for inclusion (among them, the regular census mailout, Internet response, nonresponse follow-up, unaddressed “Be Counted” forms, and foreign language forms), and the PSA’s function was to determine which persons and information to retain from the set of records bearing the same MAF ID number. In all, 8,960,245 MAF IDs had more than one eligible return (representing just less than 8 percent of the IDs on the Decennial Response File, the rawest compilation of collected census data); more than 95 percent of these IDs had exactly two returns associated with them, and 55 percent of those had two enumerator returns associated with them. The exact mechanics of the PSA are confidential, so that only a brief executive summary of the Bureau’s evaluation of the PSA’s performance is publicly available (Baumgardner, 2002), with additional results presented by Alberti (2003). What is known is that the algorithm involves grouping the set of people on a set of records into interim PSA households, with some checking of duplicates using person matching; it is also known that the census residence rules are not used in analyzing the person records possibly associated with a household, since Baumgardner (2003:iii) comments that the “[PSA] itself cannot take those rules into account when making decisions.” The Bureau carried out an ad hoc operation to identify duplicate housing units in June 2000. Internal evaluations from the first few months of the year compared the count of housing units on the MAF to estimates generated by using building permits and other sources; those analyses suggested sizable duplication in the MAF records. The operation flagged 2.4 million housing units (containing 6 million person records) as potential duplicates; these were temporarily removed from the census file. After further review, 1 million housing units (2.4 million people) were reinstated to the census file, and the rest were permanently deleted. Estimation of erroneous enumerations, including duplicate records, were a major focus of the Bureau’s work in the postcensus Accuracy and Coverage Evaluation (A.C.E.) Program. Bureau staff performed person-record matches based on name and birthdate in two waves. The Person Duplication Studies (summer 2001) matched the A.C.E. samples (two samples of approximately 700,000 records each, one of which is a direct extract from the census for selected blocks) to the nationwide census results. The Further Study of Person Duplication (summer 2002) did the same level of matching, but with revised methodology. Subsequently, Bureau researchers have extended the scope and methodology of the work, matching the entire census person-level file to itself to identify potential duplicates. This work has raised the possibility of incorporating real-time unduplication into the census process in 2010, performing the same type of nationwide matching for batches of records to identify candidates for field follow-up. The 2006 and 2008 operational tests are intended, in part, to help resolve some remaining questions about the operation, such as the ideal timing of the operation and the sequencing of a coverage follow-up interview process (meant to consolidate multiple operations from 2000, as well as provide input to unduplication) with the coverage evaluation interviews. |

Several other aspects of coverage merit comment:

-

The Census Bureau’s techniques for person unduplication in the 2010 census, including real-time processing of returns, must be fully tested in the 2006 census test and the 2008 dress rehearsal. The final shape of the unduplication program must be based on the empirical evidence gathered by these tests.

-

Perfect information is an unobtainable standard in census data collection. While electronic checks for duplication (making use of probability models for the likelihood that records are duplicates) can introduce error into census processes, so too can field verification of previously collected census data be a source of error. Accordingly, the Census Bureau should take a balanced approach to census unduplication methodology; electronic checks that can facilitate real-time corrections should be considered, and field verification should not be given undue weight as a “gold standard” for data precision.

-

To provide additional information for evaluation, the Census Bureau should consider performing complete follow-up of households flagged by unduplication algorithms for a sample of local census office workload or for sample census blocks.

-

The Census Bureau should test modifications of its computer algorithms for person unduplication to include matching on address (and ARE address), as well as name and date of birth.

8–C

CLASHING RESIDENCE STANDARDS: THE CENSUS AND THE AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY

Estimates from the American Community Survey (ACS), now in the full stages of data collection, will replace the previous census long-form sample. Collection of ACS data began in selected test sites in 1996, ultimately including about 30 test sites (counties or groups of counties) prior to the 2000 census. As a formal experiment in 2000, the Census Bureau fielded a large survey based on the sampling and residence rule anticipated for the ACS. For this survey, called the Census 2000 Supplementary Survey (C2SS), the Bureau added 1,200 counties to the initial 30 test sites and sampled 891,000 housing units. Satisfied with the operational feasibility of conducting the ACS (Griffin and Obenski, 2001), the decision to replace the census long form with the ACS (and make the 2010 census a short-form-only collection) was finalized; within the Census Bureau organizational hierarchy, responsibility for the ACS was shifted from the demographic surveys to the decennial census directorate. Data collection continued at the C2SS levels through 2004, expanding to full-scale coverage of the household population (all counties) in January 2005 and

incorporating group quarters in January 2006. In its full-scale operations, the ACS is designed for a sample size of 3 million addresses per year.

The advent of the ACS raises a variety of challenges related to the construction and interpretation of statistical estimates based on ACS data. As is the case with coverage evaluation, the estimation challenges associated with the ACS are the focus of a separate National Research Council panel. While a complete examination of the ACS is the purview of that panel, and not ours, it is necessary to have some overview of the basic structure of ACS data collection and estimates in order to understand concerns about the residence concept of the ACS. We describe two basic concepts of the ACS design in brief; for additional detail, see National Research Council (2004b), U.S. Census Bureau (2006a), and U.S. Government Accountability Office (2004b).

The first basic concept about the ACS that must be understood in the context of residence is the nature of estimates produced by the survey. Though the ACS is a large survey, its sample size of 3 million addresses per year does not match the (roughly) one-sixth sample of the nation’s households that received the census long form in previous censuses. In order to reduce their inherent variability, ACS estimates are constructed by aggregating monthly survey data over 1 or more years. Under the current system, small geographic areas with populations of less than 20,000 have estimates that are produced by combining data within a 60-month interval. Those areas with populations between 20,000 and 65,000 receive estimates calculated from data in a 36-month window (separately, a 60-month estimate is calculated for those areas as well). Finally, large areas with 65,000 population or greater yield estimates based on 12 months of data (36-month and 60-month estimates are also available). This system of overlapping (and, in some sense, competing) estimates creates challenges for comparison between areas and for assessing change in trends over time. The extent of these challenges is just now beginning to be understood, and their practical effects will begin to become known in the summer of 2008, when the first multiyear estimates (from 3 years of full-scale ACS collection) are released.

The second fundamental concept of the ACS is that it is a continuous measurement and data collection operation, using three consecutive modes of response. Every month, questionnaires are mailed to a new sample of 250,000 addresses.1 All housing units for which a form is not returned by mail within the first month are contacted by phone during the second month (provided that phone numbers are available in MAF records); data are collected using a computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) instrument. At the end of the second month, the remaining nonresponding housing units (plus any housing units that were unable to be reached by mail) are eligible

for personal visit follow-up. Only a sample of these units are approached for data collection by computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI). The important point about this structure is the continuity of the operation. A new 250,000-address sample begins this three-stage process each month, but the actual data collected and processed during a particular month are a blend of first-month mailed questionnaires, second-month CATI interviews, and third-month CAPI interviews. The reference point for each of these interviews is the time of the actual interview (or determination of vacant housing unit status). That is, a CAPI interview conducted in July asks the respondent to refer to July and not to May, when that household entered the ACS process.

Bearing these design aspects of the ACS in mind, we now consider a vitally important distinction between the ACS and the decennial census: their underlying residence standards. Both the decennial census and the ACS share the basic premise that each person has only one residence at any specific point in time (Griffin, 2005). On the continuum from de jure to de facto, the decennial census uses a hybrid “usual residence” concept that is close to the de jure end of the scale. In comparison, the residence concept used in the ACS is close to—but not purely—a de facto rule. Box 8-2 excerpts the residence rules for the ACS, as they are described in technical documentation on the design and methodology of the survey (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006a).

The ACS residence standard is described as a “current residence” or a “2-month rule,” but it is considerably more complex than the succinct terms suggest. The “2-month rule” diverges from a true de facto standard because it does not specify a complete count of all people at the contacted housing unit at the time of the interview: it is meant to exclude short-term visitors, “people only staying [at the sample housing unit] for a short period of time.” As it is articulated, the 2-month rule is meant to be prospective and retrospective—a person’s “expected length of stay,” actual or intended, is the qualification for current residence. The rule also differs from a de facto standard because it permits people to be counted at the household even if they are temporarily away. As long as people “are away from the housing unit for two months or less,” they are considered current residents; however, “people who have been or will be away for more than two months” are not deemed current residents. A more subtle point about the phrasing of the ACS rule is that it makes reference to a “short period of time” being synonymous with “two consecutive months,” but otherwise does not specify a consecutive timespan.

As Box 8-2 also indicates, the ACS residence standard includes specific exceptions to the 2-month reference period for some living situations. The ACS’ handling of boarding school students (counting them at their parental homes) is consistent with practice in the 2000 census; however, the ACS’ handling of commuter workers—counting them as current residents of their “family residence,” no matter where they might be or where they spend most of their time—differs from the census. In two other situations, a pure de facto

|

Box 8-2 Residence Rules for the American Community Survey Housing Units. The ACS defined the concept of current residence to determine who should be considered residents of sample (housing units [HUs]). This concept is a modified version of a de facto rule where a time interval is used to determine residency. The basic idea behind the ACS current residence concept is that everyone who is currently living or staying at a sample address is considered a resident of that address, except people only staying there for a short period of time. People who have established residence at the sample unit and are away from this unit for only a short period of time are also considered to be current residents. For the purposes of the ACS, the Census Bureau defines this “short period of time” as two consecutive months, and the ACS current residence rule is often described as the “2-month rule.” Under this rule, anyone who is living for more than 2 months in the sample unit when the unit is interviewed (either by mail, telephone, or personal visit) is considered a current resident of that sample unit. This means that their expected length of stay is more than 2 months, not that they have been staying in the sample unit for more than 2 months. For the ACS, the Census Bureau classifies an HU in which no one is determined to be a current resident, as vacant. In general, people who are away from the sample unit for 2 months or less are considered to be current residents, even though they are not staying there when the interview is conducted, while people who have been or will be away for more than 2 months are not considered to be current residents. Residency is determined as of the date of the interview. A person who is living or staying in a sample HU on interview day and whose actual or intended length of stay is more than 2 months is considered a current resident of the unit. That person will be included as a current resident of the unit unless he or she, at the time of interview, has been or intends to be away from the unit for a period of more than 2 months. There are three exceptions to this rule.

A person who is staying at a sample HU when the interview is conducted but has no place where he or she stays for periods of more than 2 months is also considered to be a current resident of the sample HU. A person whose length of stay in the sample HU is only for 2 months or less and has another place where he or she stays for periods of more than 2 months is not a current resident of the unit. Group Quarters. Residency in group quarters (GQ) facilities is determined by a purely de facto rule. All people staying in the GQ facility when the roster of residents is made and sampled are eligible to be selected to be interviewed in the ACS. The GQ sample universe will include all people residing in the selected GQ facility at the time of interview. Data are collected for all people sampled regardless of their length of stay in the GQ facility. Children (below college age) staying at a GQ facility functioning as a summer camp are not considered to be GQ residents. |

|

Reference Period. As noted earlier, the survey’s reference periods are defined relative to the date of the interview. The survey questions define the reference periods and always include the date of the interview. When the question does not specify a time frame, respondents are told to refer to the situation on the interview day. When the question mentions a time frame, it refers to an interval that includes the interview day and covers a period before the interview. For example, a question that asks for information about the “past 12 months” would be referring to the previous 12 months relative to the date of the interview. SOURCE: Excerpted from U.S. Census Bureau (2006a:6-2–6-3). |

standard is used for the ACS: children in joint custody living arrangements are intended to be counted where they are at the time of the interview, and all persons included in the group quarters component of the ACS are counted where they are found (no group quarters type is allowed to report a “usual home elsewhere,” as in the 2000 census).

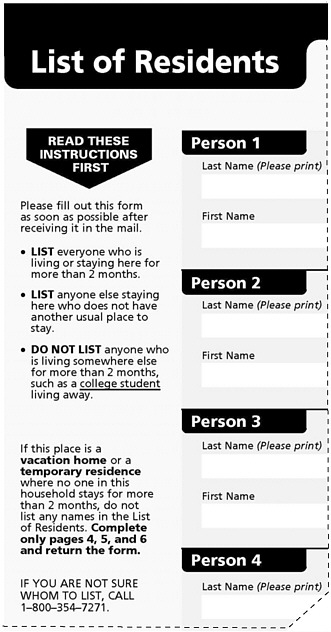

We have described the ACS residence concept in theory, but it is critical to consider how this concept is conveyed on the ACS questionnaire itself. The questionnaire booklet begins with collection of initial information from the respondent on page 1, in a box labeled “Start Here”; see Figure 8-1. Full data collection begins with constructing a “List of Residents,” laid out on a double-page spread on pages 2–3; a portion of that list, with instructions, is reproduced in Figure 8-2. What is immediately conspicuous about the presentation is that the entire first page of the questionnaire, including the household count question in the “Start Here” block, contains no reference to 2 months or any other time period. The opening set of bulleted points indicates only that the ACS questionnaire is asking for “basic information about the people who are living or staying at the address” in question, with no further explanation. The basic household count question—“How many people are living or staying at this address?”—is the counterpart to Question 1 on the census. But, unlike the census form, the ACS version of the question is not accompanied by any guidance on how this count is to be computed (e.g., people to be included or excluded). In addition, the ACS question contains no reference date (such as “April 1, 2000” on the census form), although the form does collect “today’s date” on the preceding line. Census Bureau staff performed limited cognitive testing of a version of the ACS questionnaire (31 interviews); this testing suggested considerable confusion on both the scope of “living and staying at this address” and the reference date, but the Bureau analysts recommended no change to the household count question. They suggested only that the date question be amended to read “Today’s Date” (DeMaio and Hughes, 2003).

In designing the ACS questionnaire, the Bureau chose a ledger-type approach for collecting the “List of Residents”; data on each of five household

Figure 8-1 Introductory household count question, 2005 American Community Survey

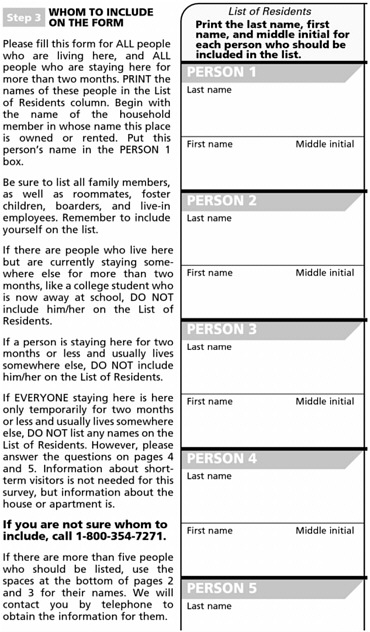

members are gathered along the rows of a two-page spread in the questionnaire booklet. A consequence of the design is that the instructions provided in order to complete the “List of Residents” (Figure 8-2) are extremely brief, limited to one thin column along the left-hand edge of the listing. The instructions take the form of two include statements (“LIST”) and one exclude statement (“DO NOT LIST”).

As articulated in Box 8-2, the ACS’ current residence standard is arguably as intricate as the usual residence standard of the decennial census, and it includes explicit handling of particular living situations. Yet what is striking about the ACS instructions is that they convey very little information about the underlying residence concept and are actually confusing. The first bulleted instruction does try to concisely capture the ideas of a current residence (“who is living or staying here”) and a prospective 2-month window. However, the second bulleted point is puzzling because it abruptly (and literally) switches to a “usual” residence perspective, directing that “anyone else who is staying here who does not have another usual place to stay” should be listed in the household. The nuance and complexity surrounding the interpretation of the word “usual” has been the motivation for most of this report, and all of that complexity certainly applies to its use in the ACS questionnaire. It is particularly jarring in this context because “usual” is especially ill defined and

confusing when it is inserted into one of the very few instructions that are supposed to explain a “current” residence concept.

According to the rule, people who are not present at the time of the interview but are away for 2 months or less are supposed to be considered current residents and included in the ACS household. The third bulleted instruction—to exclude “anyone who is living somewhere else for more than 2 months”—addresses the converse situation: it emphasizes that long-term absentees should be omitted but does not speak directly to short-term residents who should be included. The semantics of this instruction are also interesting because it uses the strong condition “living somewhere else” rather than “staying” (as in the second bullet) or “living or staying” (first bullet). This wording raises, for instance, the problem of family members who are away from home for physical rehabilitation or other such programs, possibly for 2 or more months: a respondent may consider these family members as staying somewhere else for a time, but not necessarily living somewhere else.

The ACS current residence standard lays out several exceptions to the general 2-month rule, none of which is referenced in the instructions. Indeed, the only specific living situation included in the instructions is the prominently underlined reference to college students in the third instruction. This lone example is interesting and potentially confusing, depending on when the survey is administered. Assume a calendar where college classes end in mid-May and resume in late August or early September. By the letter of the 2-month rule, college students who have returned to their parents’ homes at the end of classes ought to be reported as current residents if the ACS is administered in late May or June (the students are expected to be at the home location for just over 2 months) or in July or August (the students have been at the home location for 2 months or more). In concept, college students could also be reported as current residents in an interview at their parents’ homes in March or April—the students are away right now, but will return within 2 months. Yet what stands out from a cursory look at the instructions is a connection between “do not list” and “college student[s].” The counting of college students seems to be an instance where the ACS attempts to retain the “usual residence” character of the decennial census, though that may contradict the survey’s own “current residence” orientation.

Regarding the presentation of basic residence concepts on the questionnaire itself, two additional points should be made. First, the Bureau provides a companion booklet—“Your Guide for the American Community Survey”—that is intended to walk respondents through the questions. However, that booklet is keyed only to the numbered questions, the first of which is “What is this person’s sex?” in the columns of the “List of Residents.” That is, the companion instruction book skips the first-page “Start Here” block entirely, and provides no additional residence instructions on who should or should not be included in the resident list. Second, the features described thus far—

the “Start Here” block and basic instructions on page 2—are not solely part of the latest (2005) version of the questionnaire. Rather, these portions of the questionnaire have not changed substantively since 1999. The earliest version of the questionnaire, used in test sites between 1996 and 1998, only made reference to “living and staying here” on page 1 (without mentioning a two-month period), but did provide somewhat more detailed instructions; see the excerpt in Figure 8-3.

A separate item in the column of instructions for “List of Residents” (see Figure 8-2) is the note that the respondent should not list residents “if this place is a vacation home or a temporary residence where no one in this household stays for 2 months.” This is intended to cover cases where no one in the contacted housing unit can be considered a “current resident” under the ACS residence concept. However, the syntax of the statement is awkward because it switches verb tense: “[no one] stays for more than 2 months” rather than “[no one] is staying for more than 2 months.” Snowbirds who receive the questionnaire at their seasonal residence in March, shortly before they return “home,” could feel compelled to complete the List of Residents and fill out all the person-level information: after all, they do stay at the vacation home for more than 2 months (generally, or in the year). To the extent that this instruction is also meant to account for one of the exceptions to the general 2-month rule—namely, commuter workers who are intended to be counted at their “family home”—it is unclear how effective this instruction will be. An apartment maintained strictly for work would be unlikely to be considered by its resident as either a “vacation home” or a “temporary residence”; moreover, in the aggregate, “usual” residence sense, commuter workers do stay at their work location apartments for more than 2 months (albeit not in a consecutive block), and hence could list themselves as residents of the work location.

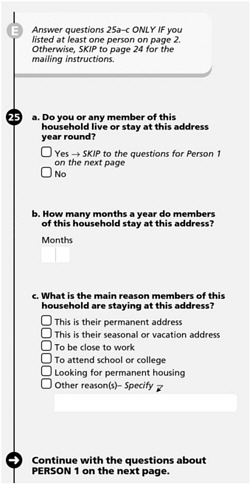

Question 25 on the ACS form, shown in Figure 8-4, was first added to the ACS in 2003 to collect more information on seasonal populations. It begins by asking whether any household member “live[s] or stay[s] at this address year round”; follow-up questions are asked only if the answer is no (that is, everyone in the household is only a part-year resident at this location). The question may provide some insight on snowbird and sunbird residences, as well as other situations like groups of college students renting a house or apartment during the academic year. However, by its design, the question falls well short of being able to provide information on a fundamental underlying question: the extent to which individuals’ “current residence” coincides with their “usual residence.”

The ACS is intended to provide information on social, economic, and demographic characteristics of geographic areas, not population counts for those areas. As a result, it could be argued that there is less of a need for an absolutely complete accounting of “current residents” in the ACS. Moreover, the nature of ACS estimates means that multiple months or years of data are

Figure 8-4 Question 25, 2005 American Community Survey

combined to produce ACS-based proportions and averages; conceptually, it is reasonable to expect some lack of precision in an estimate that is meant to be based on the population that were “current residents” of an area at some point in a 5-year window of time. It is also the case that, despite its oft-stated mandate of replacing the decennial census long form, the ACS should not be held to the exact standards and methodology of past and current censuses. The ACS is more properly thought of as a new and vital data collection system: it must be able to satisfy current uses of long-form census data, but it has unique properties, strengths, and limitations that should be examined but not impeded by complete adherence to census norms.

However, the Census Bureau is now in a position where two flagship products—the decennial census and the ACS—follow two complex residence

standards that are conceptually very different. It may be that the aggregation of multiple years of ACS data makes individual residence reporting problems offset each other and produces estimates consistent with what would be found using a “usual residence” standard. Yet it may also be that different applications of residence concepts produce highly discrepant estimates for some areas or population subgroups. Given the newness of full-scale ACS collection and—more fundamentally—the lack of collection of both residence locations on the same questionnaire, it is simply unknown how problematic the disconnect between the two programs will be.

Our recommendation for the ACS is directly analogous to our recommendation for the decennial census. We have suggested a program of research to gain further insight on how individual people’s concepts of residence match the decennial census “usual residence” concept, as well as the effectiveness of the census questionnaire in eliciting accurate “usual residence” information. The same line of reasoning holds for the ACS: it is unclear how well the ACS “current residence” concept or “2-month rule” fits with respondents’ own notions, and our review above raises considerable uncertainty as to how well the ACS questionnaire items and instructions match the survey’s own residence concept.

For the decennial census, we recommend that the Census Bureau collect “any residence elsewhere” information. As a starting point, these data should be collected as a major experiment of the 2010 census so that rigorous evaluation and analysis of those data can inform changes for later censuses. Likewise, we believe that the Census Bureau will ultimately be best served by the inclusion of a usual residence question in the ACS questionnaire, asked of each person and not of a whole household. The collection of both types of residence information is essential to measuring discrepancies between the residence standards and for evaluating the residence concepts of both the census and the ACS. As a first step—a means to gather baseline information for evaluation and refinement of a full-scale implementation of the question—the Bureau should include a usual residence question in its ACS experimentation. Current plans for the ACS include a “methods panel,” a subset of the ACS sample that may receive experimental versions of questionnaires or revised wordings of specific items. This methods panel would be an ideal setting for asking respondents whether their current residence is what they consider to be their usual residence and, if not, where their usual residence is.

Recommendation 8.3: The Census Bureau should plan to ask a question on the usual residence of each household member in the ACS questionnaire, in order to evaluate the extent of incongruity of residence standards between the long-form replacement survey and the decennial census. The usual residence question should first be tested using the survey’s experimental

“methods panel”; the resulting data should be fully evaluated and analyzed to refine final versions of the question.

The frequency of data collection in the ACS makes it a potentially useful vehicle for getting survey coverage of seasonal populations, such as snowbirds, sunbirds, and migrant workers. Yet to make effective sample sizes more consistent with the long-form sample, the Census Bureau is relying on a release schedule where data are aggregated over 1, 3, or 5 years. Adhering to this plan, the Census Bureau has resisted pressures to issue other releases that may capture the seasonal nature of some populations within a year. However, in conjunction with our recommendation to continue studies of trends related to residence and key population subgroups, we encourage the Bureau to consider ways to use the ACS for information on seasonal differences.2

8–D

TESTING AND RESEARCH IN 2010 AND BEYOND

We argue in this report for a new approach to residence in the census, centered on the derivation of a core set of residence principles. Working with these principles—in particular the precept that usual residence should be an individual-level determination and not an attribute of a specific housing type or population group—suggests the need to ask more residence-related questions on the census form than in the past. We also recommend question-based structure for eliciting resident listings and counts as ultimately more effective than the current instruction-based approach.

Recommendation 8.4: A major test of census residence concepts, conducted in conjunction with the 2010 census, should be the basis for postcensal development leading to the 2020 census. This test should include both a question-based approach to collecting resident count information and a provision for ARE reporting by all census respondents, including those living in group quarters (nonhousehold) situations.

In the long term—from the 2010 to the 2020 census—a thorough evaluation of the results of the test and the design of any follow-up work is a major research priority (Recommendation 6.5), as is specific analysis of the returns

from incarcerated persons in order to assess the feasibilities of allocating prisoners to a geographic location other than the prison (Recommendation 7.2). It will also be useful to compare and contrast the ARE information with that generated by related operations—the proposed coverage follow-up operation (Box 6-3) and the postenumeration survey used for coverage evaluation—where more detailed banks of coverage and location probes are permissible (Section 6–E.4).

In the nearer term, we suggest throughout this report a number of deficiencies in current research that should be investigated as part of an ongoing research program at the Census Bureau:

-

assessing the quality, accessibility, and relevant content of facility and administrative records for group quarters and nonhousehold facilities (Section 7–D.1);

-

studies that can provide quantitative information (and validate hypotheses based on qualitative techniques like ethnography) on the magnitude and trends in complex and ambiguous living situations (Section 5.2);

-

basic research on living situations as reflected by census operations, such as the tendency for household members to be listed, roughly, in reverse order by age (Section 5–B.3);

-

mode effects on response, including both the effects of the mode of administration (e.g., paper versus telephone response) and the general structure of roster types (e.g., whether a question-based or instruction-based approach is easier to follow) (Recommendation 6.4);

-

effects of visual layout and wording on census questionnaires (Recommendation 6.7); and

-

impact of length of form (number of questions) on survey response (Section 6–G).

It is with problems like those listed as the shorter-term research tasks in mind that we offer additional comment on the shape and direction of the Census Bureau’s general research and testing program.

8–E

THE CENSUS BUREAU RESEARCH AND TESTING PROGRAM

The most prominent components of the Census Bureau’s research program are the suite of formal experiments and tests that accompany each decennial census, the evaluation reports of various census operations that are produced after the decennial count, and the set of large-scale tests scheduled regularly between census years. These tend to be large and complex activities—indeed, one of the usual census tests is a dress rehearsal that tries to

mimic every decennial census operation—and the tests attempt to vary several major factors simultaneously. For example:

-

The 2003 National Census Test involved approximately 250,000 households using only mailed questionnaires (no field follow-up was performed); it varied both the wording of the race and Hispanic origin questions as well as different cues to respond to the test by mail, Internet, or telephone.

-

The 2005 National Census Test included a variety of coverage probe questions related to residence (see Chapter 6). In addition to those changes, though, the test also included experimental panels where Internet response is encouraged, and it included a panel that received a bilingual English/Spanish questionnaire.

-

In addition to the Alternative Questionnaire Experiment (AQE) that was conducted alongside the 2000 census, other major experiments conducted at the same time included the C2SS (a prototype for the long-form-replacement ACS), the Response Mode and Incentive Experiment, and the Social Security Number, Privacy Attitudes, and Notification Experiment.

-

The 1998 dress rehearsal that preceded the 2000 census was intended to be a true dress rehearsal, but the political circumstances that made it difficult to finalize the basic design of the 2000 census forced the 1998 “dry run” to be a particularly ambitious test. Staged in three sites, the 1998 rehearsal was actually a test of three broad design choices that varied in the degree to which nonresponse follow-up was conducted (either in full or only for a sample) and whether a postenumeration survey was used to adjust the counts for estimated nonresponse.

At the other extreme of testing in the census hierarchy are the small numbers of cognitive tests to which revised questionnaires are routinely submitted; see Box 8-3. Hunter and de la Puente (2005) tested a version of the “worksheet” approach used in the 2005 census test based on 14 cognitive interviews, conducted in the Washington, DC area in early 2005. Other cognitive tests conducted by the Bureau use similar-sized samples. Hunter (2005) reported on a 2003 test intended to see whether a proposed direct question on cohabitation (for possible inclusion on other surveys and not the census) was “direct, gender-neutral, non-offensive, and generally applicable.” Conclusions were drawn from a set of interviews with 19 people, all of whom were cohabiting at the time of the interview; the sample included both heterosexual and gay and lesbian respondents. Likewise, Hunter and DeMaio (2005) tested revisions to three separate census questions—housing tenure, age (adding a reminder to report babies as age 0 if they were less than 1 year old), and relationship—based on 18 cognitive interviews, the set of which contained

|

Box 8-3 Cognitive Testing When faced with a question during a survey interviewer, a survey respondent must perform several basic tasks in cognitively processing the question and formulating a response. Cognitive testing of survey instruments has emerged as a fairly standard practice for getting a sense of the basic thought processes stimulated by sets of questions. Tourangeau (1984), summarized by Willis (1999), identifies the major focus areas of cognitive testing, grouped by the basic cognitive task being performed by respondents:

Cognitive interviews typically follow one or both of two basic models (Willis, 1999). The first, “think-aloud interviewing,” consists of urging and cuing respondents to talk through their thought processes as they answer each question; while this method can generate a rich array of information, it also puts almost the entire burden on the respondent rather than the interviewer. The second technique, verbal probing, is more structured: a question is read and a response is given, and the interviewer then asks a set of probing questions as to how the answer was generated. These probes may include paraphrasing (“Can you repeat the question I just asked in your own words?”), comprehension/interpretation (“What does the term X mean to you?”), or more general assessments (“Was that easy or hard to answer?”). Cognitive testing may occur as an iterative process. The first draft of a questionnaire will lead to an initial set of interviews with a small number of subjects (5–10). Based on that initial feedback, results are generated and the questionnaire is designed; other rounds of testing may result as the questionnaire is successively refined. In this manner, when multiple rounds of testing are anticipated, early rounds of cognitive interviews may concentrate on general concepts, while the later rounds focus on specific question wording and structure concerns. |

different mixes of people directly affected by the question changes (10 of 18 were renters rather than owners and 6 of 18 were in households with infants).

As we have observed the development of the mid-decade census tests, the panel has grown concerned about the fact that there seems to be very little experimentation and testing by the Census Bureau that operates between these two extremes.

Finding 8.2: The Census Bureau often relies on small numbers (20 or less) of cognitive interviews or very large field tests (tens or hundreds of thousands of households, in omnibus census operational tests) to reach conclusions about the effectiveness of changes in census enumeration procedures. As a consequence many important questions about the effectiveness of residence rules do not get addressed effectively.

To be clear, we do not suggest by this finding that there is anything necessarily wrong with tests that operate at these extremes. In particular, we do not mean in any sense to malign small-sample cognitive testing as a research tool by the Census Bureau; cognitive tests are definitely worth doing, since they are an excellent diagnostic process (and generator of research hypotheses) that can identify major problems with specific questionnaire items and formats and can highlight problems in logic and syntax. What we do argue is that it is possible to put too much weight on cognitive tests, whose sample sizes are too small and unrepresentative to support broad conclusions; filtering possibilities and eliminating potential approaches to practical census problems on the strength of comments from a very small number of interviews is too restrictive.

Likewise, there is benefit to the massive scale census tests (or, more precisely, operational trials) that the Census Bureau regularly conducts. Particularly important is that they allow the Census Bureau to keep its field “machinery” well trained and in good working order; the sheer sample size that is possible in some of these trials also affords a variety and depth of response that is difficult to obtain through different means. However, the omnibus census tests also have conceptual weaknesses, as discussed in this report. By trying to coerce problems into a catch-all test, it is easy to “design” a test for which the great advantage of sample size is offset by the fact that the test reaches relatively few people who are most directly affected. As a previous study (National Research Council, 2004b) concluded, the 2003 census test—a major goal of which was to test the effectiveness of altered wording of the Hispanic origin question—was severely impaired because the test failed to adequately target responses from Hispanic communities. Also, even a relatively simple large-scale test—the 2000 AQE—can suffer from being forced into a large-test framework. Box 6-2 describes how the 2000 AQE questionnaire

block varied so many factors simultaneously that the effectiveness of any single change is impossible to determine.

Put simply, the panel’s concern is that the Bureau tends to waste test cases because it does not target relevant populations effectively. More significantly, the overall direction of the Bureau’s testing efforts is impeded by the lack of a thread of sustained research; test topics seem to arise on essentially an ad hoc basis, rather than following a more iterative series of tests designed to achieve specified goals.

Recommendation 8.5: The Census Bureau should undertake analytical research on specific problems in order to better evaluate the effectiveness of residence and other questions on the census forms. These studies should be designed to focus on particular populations of interest. Candidates for such research include:

-

why babies are often omitted from the census form (targeted at households with newborns);

-

whether census respondents find a pure de facto residence rule easier to follow and interpret than a de jure rule (generally, and with specific reference to large households);

-

whether additional residence and location probes on questionnaires—increasing the length of the survey—impairs response or other operational activities (e.g., page scanning);

-

the difficulty and advantages of including a reference date or time frame;

-

multilingual and linguistically isolated households; and

-

whether the Census Bureau standard of “live or sleep most of the time” is consistent with respondent notions of “usual residence.”

Sustained research needs to attain a place of prominence in the Bureau’s priorities. The Bureau needs to view a steady stream of research as an investment it its own infrastructure that—in due course—will permit more accurate counting, improve the quality of census operations, and otherwise improve its products for the country. Given the scarcity of resources available to it, the Census Bureau needs to explore ways to facilitate additional analysis of its extant data resources by outside researchers. Specific mechanisms by which this may be achieved include public and private partnerships for analysis of census data, renewal and extension of American Statistical Association/National Science Foundation Census fellowships, improved task-order relationships, and enhanced Research Data Centers.

The mechanics of censustaking have changed greatly since marshals were first sent out on horseback in 1790; as times have changed, the “usual residence” concept has endured even though its exact interpretation has shifted. The most recent paradigm shift in defining residence in the census came with the adoption of mail-based enumeration for most of the census population in 1970; that shift included drawing a linkage between census residence and a specific mailing address. Looking ahead, over the long term, the Census Bureau research program needs to consider broader shifts that lie ahead—the impact of the Internet and e-mail and the diminished importance of traditional mailing addresses (and paper mail) in people’s lives, more transitory living arrangements, and the changing need for census data as private and public databases grow in completeness.