–3–

The Nonhousehold Population

AN INEVITABLE TRUTH in every decennial census is that there are groups of people who are extremely difficult to count. In some cases, their living situations make it difficult to accurately gather data from them by standard enumeration techniques or even to locate them at all. In other cases, they may simply be unwilling or unable to provide accurate information even if a questionnaire reaches them. This is the first of two chapters in which we focus on groups of people who may have multiple residences (making it difficult to specify one “usual residence”) or whose ties to any fixed residence are ambiguous. In addition, we identify groups that are not explicitly covered by current census residence rules or that have historically proven difficult to count by the standard census methods and questionnaires. This listing of complex living situations is by no means exhaustive, but is intended to provide concrete examples of the breadth of difficulties in defining residence.

In each case we attempt to give some indication of what is known about the size of the group; this is important because not all the groups are the same in terms of the magnitude of the problems they present to the census count. Ultimately, as the Census Bureau and other agencies work on approaches to reach these problematic groups, some sense of prioritization is needed in order to make effective use of time and resources. However, there are cases in which no real quantitative assessment of a group’s size is possible; instead, we rely on qualitative impressions. For each group, we also indicate how the group was handled under the 2000 census residence rules as well as past censuses.1

We begin in this chapter with some major segments of what the Census Bureau has traditionally termed the “group quarters” population (Section 3–A). Among these groups are students at colleges and boarding schools (3–B), patients of health care facilities (3–C), and persons serving terms in correctional facilities (3–D). As we argue in more detail in Chapter 7, we believe that term “group quarters”—indeed, the very concept—deserves reconsideration and revision. We prefer the nomenclature “nonhousehold population,” but still use “group quarters” in this and later chapters for consistency with past work. We also include in this chapter two groups that blend elements of group quarters and standard household enumeration. Children in foster care (3–E) are predominantly placed in individual family homes but may also reside in group home or semi-institutional settings, and they may transition between these settings with some frequency. Likewise, the domestic military population (3–F) includes both barracks housing on military bases as well as housing in surrounding communities. (Of course, the general issue of counting of the military population raises issues related to the enumeration of American citizens stationed or living overseas; we discuss the overseas aspects in Appendix C.)

3–A

THE CONCEPT OF “GROUP QUARTERS”

Before discussing large classes of group quarters, it is useful to first describe how the general concept has evolved in past censuses.

Some tabulations of the 1900 census drew a distinction between “private families” and “families not private,” and the latter category was subdivided into the categories “hotel,” “boarding,” “school,” “institution,” and “other.”2 The 1930 census was the first to make a firm differentiation between places like institutions, prisons, and boarding houses as distinct from more conventional households. Dubbed “quasi-households” in that census and in 1940, and “nondwelling-unit quarters” in 1950, this segment of the population was subsequently renamed “group quarters”: the label has endured since then, even though the exact definition and distinction between group quarters and the household population have evolved from census to census.

Most censuses since 1930 have used some numerical standard to define group quarters: the 1930 and 1940 censuses defined 12 unrelated people living

in the same unit as a group quarter, the 1950–1970 censuses used 5 or more unrelated people, and the 1980 and 1990 censuses used 10 or more unrelated people (Ruggles and Brower, 2003:75). However, the 1980 census also began the practice of declaring some types of living facilities—notably, college dormitories, as well as some hospitals and missions or flophouses—as “non-institutional group quarters” regardless of the number or relationship of the people within those units. This approach was used in the 2000 census: types of places were designated as group quarters in advance, without any numerical criterion in the definition of “group quarters.”

Table 3-1 lists the 2000 census totals for the group quarters population, divided by group quarters type. The major groups in that listing—college students, patients in health care facilities, and persons in correctional facilities—are also significant cases where residential ambiguity and census error are potential problems. Before discussing issues specific to each group, we note five issues that are common across the groups.

The first general issue is competing claims as to where facility population should be counted. The size of the population of group quarters facilities makes the geographic placement of the group in census tabulations a sensitive issue, politically and economically. Colleges and universities, prisons, and military bases (with on-base housing) can account for large shares of the overall population and job base of cities, towns, and counties, and—in the quest for allocated state and federal funds—areas that house facilities have a strong incentive to have the facilities counted in their population tallies. However, the various facility types are not the same in how they fit the specifications of funding programs: for example, by virtue of their ability to move around and seek employment outside the facility, the populations of colleges and military installations are arguably more service needy and factor heavily into local areas’ planning of almost all activities. By contrast, the inherently less mobile and more insular populations of prisons are less likely to play a role in, say, local transit funding and education decisions; however, the prison population may need to be covered by local fire and emergency response personnel, and so be accounted for in those allocations.

The second broad issue involves gradations in the length of stay. Large group quarters segments differ greatly in the expected length of stay of their residents. College and boarding school students live in dormitories during the 8–10 months of the academic year, and the dormitories are largely vacant during the summer months. Health care facilities like hospitals and nursing homes can hold patients for stays ranging from hours (emergency room visits and admissions) to weeks (short-term physical rehabilitation stays at nursing facilities) to years (long-term nursing home assignment), and individual patients may cycle back and forth between home and hospital stays. Likewise, local jails may hold inmates for a matter of hours but may have to hold some for weeks or months (e.g., incarceration during a trial), and prison sentences

Table 3-1 Group Quarters Population by Group Quarters Type, 2000 Census

|

Group Quarters Type |

Population |

|

Institutionalized Population |

4,059,039 |

|

Correctional institutions |

1,976,019 |

|

Federal prisons anddetention centers |

154,391 |

|

Halfway houses |

30,334 |

|

Local jails and other confinement facilities (including police lockups) |

623,815 |

|

Military disciplinary barracks |

20,511 |

|

State prisons |

1,077,672 |

|

Other types of correctional institutions |

69,296 |

|

Nursing homes |

1,720,500 |

|

Hospitals/wards, hospices, and schools for the handicapped |

234,241 |

|

Hospitals/wards and hospices for chronically ill |

40,022 |

|

Hospices or homes for chronically ill |

7,682 |

|

Military hospitals or wards for chronically ill |

1,944 |

|

Other hospitals or wards for chronically ill |

30,396 |

|

Hospitals or wards for drug/alcohol abuse |

19,029 |

|

Mental (psychiatric) hospitals or wards |

79,106 |

|

Schools, hospitals, orwards for the mentally retarded |

41,857 |

|

Schools, hospitals, orwards for the physically handicapped |

20,765 |

|

Institutions for the deaf |

2,325 |

|

Institutions for the blind |

1,885 |

|

Orthopedic wards and institutions for the physically handicapped |

16,555 |

|

Wards in general hospitals for patients who have no usual home elsewhere |

23,538 |

|

Wards in military hospitals for patients who have no usual home elsewhere |

9,924 |

|

Juvenile institutions |

128,279 |

|

Long-term care |

71,496 |

|

Homes forabused, dependent, and neglected children |

19,290 |

|

Residential treatment centers for emotionally disturbed children |

12,725 |

|

Training schools for juvenile delinquents |

39,481 |

|

Short-term care,detention or diagnostic centers for delinquent children |

29,437 |

|

Type of juvenile institution unknown |

27,346 |

|

Noninstitutionalized Population |

3,719,594 |

|

College dormitories (includes college quarters off campus) |

2,064,128 |

|

Military quarters |

355,155 |

|

On base |

310,791 |

|

Barracks,unaccompanied personnel housing (enlisted/officer), and similar group living quarters for military personnel |

281,416 |

|

Transient quarters for temporary residents |

29,375 |

|

Military ships |

44,364 |

|

Group homes |

454,055 |

|

Homes or half way houses fordrug/alcohol abuse |

94,243 |

|

Homes for the mentally ill |

63,912 |

|

Homes for the mentally retarded |

148,043 |

|

Homes for the physically handicapped |

16,119 |

|

Other group homes |

131,738 |

|

Religious group quarters |

78,102 |

|

Dormitories |

97,697 |

|

Agriculture workers’ dormitories on farms |

47,664 |

|

Job Corps and vocational training facilities |

32,143 |

|

Other workers’ dormitories |

17,890 |

|

Crews of maritime vessels |

4,523 |

|

Other nonhousehold living situations |

95,565 |

|

Other noninstitutional group quarters |

570,369 |

|

Total |

7,778,633 |

|

SOURCE: 2000 Census Summary File 1, tabulated through http://factfinder.census.gov. |

|

can range from months to life. This gradation in the possible length of stay at facilities can create residence conundrums for census respondents and their families—if a household member is expected to return home from a hospital stay in a few days/weeks/months, should they be counted at their home or at the nursing facility? And, as we discuss in more detail later, should prisoners be counted at a “home of record” rather than a prison location and, if so, should remaining time left in a prisoner’s sentence (e.g., 3 months or natural lifetime) be a factor in making that determination?

The third general issue concerns the continuum of attachment to a facility. Consistent with the variation in lengths of stay at facilities, the group quarters population spans a continuum of levels of attachment to the facility. The population blends groups of people who are unequivocally in the facility as a usual residence (they have no other residence outside the facility) with those who have strong ties to a usual residence elsewhere.

In a different vein, the fourth general issue is the presence of a “gatekeeper” or other barriers to direct enumeration. Residents of large group quarters also vary greatly in the degree to which direct enumeration—distribution of questionnaires to be filled out directly by residents—is either feasible or permissible. Some college campuses, eager to get as complete a count as possible, may encourage such direct contact. Others—citing resource constraints or the magnitude of the job—may insist that enumeration not be done directly and that university records be used. Hospital and group home residents may be physically incapable of completing forms on their own, requiring special enumeration methods or reliance on administrative records. And, finally, prison administrators may cite safety concerns in prohibiting any direct contact with their inmate populations.

Lastly, there are complicated address listing issues that affect all groups. As examined in greater detail in Chapter 7, it can be difficult to maintain an accurate and up-to-date roster of group quarters units, and—if the lists of group quarters and “regular” housing units are kept separate—duplication or omission can occur if the two lists are not reconciled. An analysis of the 2000 census public-use microdata sample (Ruggles, 2003:481) concluded that the Census Bureau’s decision to scrap a rule that would define a group quarters on the basis of a set number of unrelated individuals living together was largely inconsequential because only 42 households in the sample would have been declared group quarters using such a rule (using the 1990 cutoff). However, many of these stray households appear to be clear cases in which buildings were misclassified and errors were made in listing group quarters facilities: these “large households” consisted entirely of college students, farm laborers, or construction laborers.3

Large institutional group quarters may also have housing units that should rightly be contacted by usual census methods like mailout/mailback: college dormitories may include rooms for resident assistants who maintain a permanent residence there; boarding schools may likewise have permanent onsite resident faculty and staff quarters; and contemporary nursing homes may blend apartment-style assisted living units with more institutional, hospital-like nursing beds in the same facility.

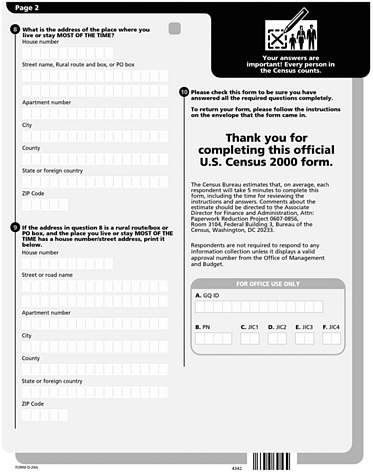

It should also be noted that the questionnaire used to enumerate group quarters residents differs somewhat from the general household questionnaire. Group quarters resident information was to be collected on Individual Census Reports (ICRs), or customized versions for the military and shipboard populations; see Box 3-1. In addition to the ICRs—one per person—enumerators of group quarters facilities were expected to complete a general roster of residents. The general roster and every ICR were supposed to be marked with the same group quarters identification number (the space for which is shown on page 2 of the ICR in Box 3-1).

3–B

STUDENTS

3–B.1

Colleges and Universities

As Lowry (1987:15) observed, “[college] students are individually transient—each year many leave never to return—but as a class they form a permanent component of the local population that must be served in various ways by local government.” As a large group of people with strong ties to two locations, college students have understandably been prominent in census residence issues from the outset. College students were the focus of one of the first formal census residence rules (see Section 2–B.1), and were the focus of one of the most significant changes to the rules in recent decades.

Enumerator instructions for 1850 directed that college students be “enumerated only as the members of the family in which they usually boarded and lodged on the 1st day of June.” Instructions for the 1870 census clarified that “children and youth absent for purposes of education on the 1st of June, and having their home in a family where the school or college is situated, will be enumerated at the latter place.” Whether the student was to be counted at home or school would depend on the course of study and whether students returned home at the end of the academic calendar. The 1880–1900 census instructions signaled a clearer inclination for counting students at their parental homes, although that specific language was not explicitly used. A college student was identified by the 1880 instructions as a person for whom the enumerator “can, by one or two well-directed inquiries, ascertain whether [there] is any other place of abode within another district at which he is likely to be reported.” (Similar text is included in the subsequent census instructions.) The

exact resolution if such a home elsewhere was found (the parental home) was not made clear, but the implication is that students were not to be counted if found at school if they were already counted at home. No specific mention of college students (distinct from general boarders) are made in enumerator instructions between 1910 and 1940, preserving the notion of counting college students at their parental homes.4

In 1950 the Census Bureau reversed the rule and concluded that the students should be counted at the place they were living while attending college. Bureau documentation ascribes the change to the desire for consistency with “usual residence”—“most students live in college communities for as much as nine months of the year, so the college is their usual residence”—but also because it was believed that the count would be more accurate since students “were often overlooked in the enumeration of their parental homes” in past censuses (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1955:11). In part, this shift owed to the evolution of the “usual residence” concept, but it also reflected a significant demographic fact of the times—following World War II, large numbers of returning veterans became college students with assistance from the GI Bill. Accordingly, the basic demography of college campuses shifted from a children-away-from-home model to an adult education model, and considering students’ school residences as their “usual” residences was consonant with that shift. The rule change in 1950 created a substantial shock in demographic data series that future analysts would have to consider: “63.7 percent of students aged 18 to 22 resided without family in 1950, compared to just 7.0 percent in 1940” (Ruggles and Brower, 2003:82).5

The size of the college population, as a whole but particularly as a share of many cities and towns, makes the question of where college students should be counted a contentious one. In this respect, the college population is similar to the military and incarcerated populations: they are all instances where slight variation in the census residence rules can dramatically alter the demographic portrait of local areas (and the state and federal fund allocations to those areas). The counting of the college population has thus been challenged over time, but the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1971 decision in Borough of Bethel Park v. Stans (see Box 3-2) upheld the Census Bureau’s right to make a rational determination as to where college students and other institutional populations should be counted.6 For purposes of constructing its legislative districts and allocating state funds, the state of Kansas disagrees with the Census Bureau’s

interpretation; the state fields its own decennial survey to “adjust” where college students (and military personnel) in the state are counted. We discuss Kansas’ approach in Box 7-2 in Chapter 7.

In the 2000 census, college students were the explicit focus of 3 of the 31 formal residence rules. Students who live at home while attending college are to be counted at home (Rule 6); those who live away from the parental home while attending college and are “only here during break or vacation” are to be counted at their residence at college (Rule 5); and students living in a group quarters (such as a dormitory or a fraternity or sorority house) are to be counted at the group quarters (Rule 25). Two other rules address college students indirectly; foreign students studying in the United States on Census Day are to be counted at their household location in the United States (Rule 11), while U.S. students studying abroad are excluded from the census (Rule 29).

The standard of counting college students at the college location had been revisited by Bureau staff working groups prior to the 2000 census, and the decision to retain it was not a unanimous recommendation. As Rolark (1995:5) comments, “some members of [the Bureau team] felt very strongly that we should allow all college students to claim a [usual home elsewhere] in the 2000 census”—presumably, students could claim and be counted at their family home. However, the Bureau’s steering committee for the census rejected the change. Instead, “there was general agreement [on] the need to educate respondents on the correct procedure for reporting students away at college,” and the committee indicated that it would be important “to collect ‘hard’ data on the reporting habits of college students and their parents” (Rolark, 1995:Comments on Rule 5).

College students are a challenging population to count accurately because they present difficulties on many different levels, both in terms of definitions and operations and because of potential misunderstandings by both students and parents. Three major difficulties are students’ independence versus their familial ties, the variation in kinds of college residences, and the academic calendar.

Student Independence Versus Parents’ Enduring Ties

For most college students, aged 18–24, the college years are an important time of transition from dependence on parents to independent adulthood. In

|

Box 3-2 Borough of Bethel Park v. Stans (1971) Plans to include overseas U.S. military personnel and their dependents in the state-level apportionment counts in the 1970 census, based on “home of record,” occasioned a major challenge to the Census Bureau’s practices in counting other special populations. Several Pennsylvania municipalities and other parties brought suit against the U.S. Secretary of Commerce and the census director, arguing that the Bureau’s residence standards for college students, military personnel, and the institutionalized population violated the Constitution and the Census Act. Specifically, the Pennsylvania municipalities argued that their populations were undercounted because college students, domestic military personnel, and institutional inmates were counted at the location of the facilities rather than the place that those individuals might consider their “legal residence for all purposes other than the census.” The appellants approved of the Bureau’s new policy of siting federal and military personnel and dependents stationed overseas at their “home of record,” but argued that they should be assigned to specific addresses (and not just included in the state-level apportionment totals). After a district court ruling sided with the Census Bureau, the city of Philadelphia and Rep. James Fulton (R-Pennsylvania) appealed the case; the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit rendered its judgment in Borough of Bethel Park v. Stans (499 F.2d. 575) on September 30, 1971. Although the Court of Appeals noted that the current U.S. Code contains no attempt of definition of “usual residence” akin to the Census Act of 1790, the court said that “it has been stipulated that the following criterion was used by the Bureau of the Census to determine usual place of residence for the 1970 Census: ‘Persons are enumerated at the place in which they generally eat, sleep and work, with persons who are temporarily absent for days or weeks from such usual place of abode being counted as residents of their usual place of abode.’” The Court held that this criterion is a “historically reasonable means of interpreting” the Constitutional and legislative mandate of the census. The 1970 census was only the third in which college students were counted at their schools rather than parental homes. “Once a person has left his parental home to pursue a course of study at a college in another state which normally will last for a period of years, it is reasonable to conclude that his usual place of abode ceases to be that of his parents.” The Court of Appeals was not swayed by the appellant’s argument that, “if an individual college student indicates that he feels a particular connection or attachment to the state of his parental home, registers to vote in that state, and accordingly regards it as his home, the Bureau should consider these facts in determining his residence for the purpose of the census enumeration.” Instead, the Court ruled that “the Bureau is entitled to limit its inquiry to the objective facts as to where the student chooses to generally eat, sleep, and work—the state of his college rather than the state where his contacts are substantially reduced.” This gives the Bureau a “definite, accurate and verifiable standard.” [In a footnote, the Court also accepted the Bureau’s practice of reversing course and counting boarding school students at the parental home.] Using similar logic, the Court also found that “appellants have failed to impugn the Bureau’s exercise of discretion” regarding the military and institutional populations. Accepting the Bureau’s assertion that allocating overseas federal and military personnel to specific addresses or to levels of geography below the state “would be an impossible task,” the Court held that the Bureau’s decisions “possessed a rational basis.” Likewise, “persons confined to institutions where individuals usually stay for long periods of time” (as contrasted with short hospital stays) are counted “as residents of the state where they are confined” under census rules. “We think that the decision of the Bureau as to the place of counting institution inmates has a rational basis,” concluded the Court. |

many cases, college represents the first extended period of being away from their family home; the peak college age group straddles important legal and cultural thresholds of adult responsibilities at ages 18 and 21 (e.g., voting, Selective Service enrollment, and legal ability to consume alcohol). We also noted in Chapter 2 the intricacies of qualifying for resident status for purposes of college tuition and how that may conflict with other residence standards. College students are also of the age where they can begin to take on financial burdens in their own right (e.g., taxes on employment income or student loans). These and other factors can lead to contradictory impulses in college students’ minds when they are asked where they reside—the new independence (and burden) of their college life may lead them to identify with their college community, but the tie to family homes may be just as strong.

At the same time, parents may have strong impulses to list their college student sons and daughters when asked who lives at their household—whether or not that coincides with Census Bureau notions of residence and regardless of clear instructions on how students are to be counted. In many cases, it is the parents who bear the substantial costs of college tuition; strength of kinship ties aside, the financial tie of paying for student tuition alone may induce some parents to count college students as part of their household. The “enduring ties” philosophy makes it counterintuitive to many parents to exclude their children from a list of household members. Therefore, there is a conflict between the subjective feelings of both parents and students and the census residence rules, which can lead to both omission (college students assuming that they are counted at “home” and not completing a form at their school location) and—particularly—duplication (being counted at both the college and home locations).

Variation in College Housing Types and Options

College housing options can be divided into on campus (dormitories, graduate and married student housing, residential colleges, and fraternity or sorority houses) and off campus, for which the basic distinction is whether the school serves as the effective landlord. Both these broad categories present their own challenges.

First, students living in college-owned on-campus facilities are generally tied to the academic calendar; they live at the on-campus location during the academic year but do not (and most often cannot) live there during the summer months. Colleges and universities vary in the extent to which they require students to live on campus; some require college freshmen to live on campus and others may require students to live on campus during part or all of their college career. However, they need not live in the same specific room or hall during the entire time; from year to year, the population in residence calls can be highly dynamic. More salient for purposes of a census, on-campus liv-

ing arrangements vary significantly in the style of housing, from traditional dormitories with shared bathroom facilities, common dining halls, and with postal boxes in the building or at a student union to rooms and suites that are indistinguishable from regular apartments.7 (Indeed, in attracting students, colleges and universities have diversified their housing stock—adding more apartment-style living, with ready access to fitness facilities and other amenities.) It is possible that more apartment-style and “independent” living may encourage students to more naturally think of the college residence as their usual residence (even if that does not square with their parents’ notions).

Second, off-campus housing options for college students include apartments, either alone or in conjunction with other students, or cooperation in leasing a home with peers. In principle, these students should be enumerated in the same manner as the general population, through receiving a form in the mail and returning it. While the act of leasing an apartment or part of a house creates a strong link to the college location, an enduring tie can remain to the family home. In many cases, students’ parents may be cosignatories on leases and may contribute part or all of rent payments, further leading parents to count their at-college students as part of their household.

Of course, some students may be able—and choose—to attend college without leaving their parents’ home, depending on the location of the school.

As shown in Table 3-1, the 2000 census counted 2,064,128 students in dormitories or college-owned quarters on or off campus. With data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, a survey conducted every 4 years by the National Center for Education Statistics, Table 3-2 shows students’ living arrangements while enrolled in college. Among full-time enrollees at 4-year universities (public and private), the data suggest that about 40 percent of undergraduates live in on-campus housing; 42 percent live in off-campus housing; and about 18 percent live with their parents.

By comparison, for 2-year (community or junior) colleges and private for-profit schools, the combination of off-campus housing and living with parents accounts for about 97 percent of full-time enrollees. On-campus housing in residence halls is not the exclusive province of 4-year institutions; some community colleges (particularly in rural areas, with large service districts) offer on-campus housing, and other community colleges may view adding housing options (either residence halls or partnerships with off-site apartments) as means for attracting students.

|

7 |

At some urban universities, it is not uncommon for the school to acquire apartment buildings or hotels for conversion to residence halls (see, e.g., http://www.bizjournals.com/ washington/stories/1999/05/31/story4.html [8/1/06] on George Washington University’s conversion of the 193-room Howard Johnson Premier Hotel—best known as the lookout point during the 1972 Watergate break-in—to a student residence hall). These types of conversions further complicate the task of making sure unit listings for those buildings are listed correctly and handled by the proper enumeration method. |

Table 3-2 Undergraduate College Housing, 2003–2004

|

|

Housing |

|||

|

Student and Institution Characteristics |

On Campus |

Off Campus |

With Parents/Family Home |

Total |

|

Class Level |

||||

|

Freshman/1st year |

959.6 |

3,403.0 |

1,967.4 |

6,330.0 |

|

Sophomore/2nd year |

666.0 |

2,548.5 |

1,270.6 |

4,485.2 |

|

Junior/3rd year |

484.1 |

1,518.5 |

503.2 |

2,505.8 |

|

Senior/4th year |

435.6 |

1,625.8 |

424.6 |

2,486.0 |

|

5th Year+ or unclassified |

86.1 |

1,428.0 |

302.9 |

1,817.0 |

|

Student Enrollment Status and Institution Type |

||||

|

Full-time/full-year, public 4-year |

1,166.3 |

1,629.0 |

660.0 |

3,455.4 |

|

Full-time/full-year, private 4-year |

876.3 |

518.6 |

247.1 |

1,642.0 |

|

Full-time/full-year, public 2-year |

63.0 |

814.2 |

922.9 |

1,800.1 |

|

Full-time/full-year, private for-profit |

9.7 |

321.3 |

121.2 |

452.2 |

|

Part-time/part-year, single institution |

516.8 |

7,240.3 |

2,517.2 |

10,274.3 |

|

Lived with Parents While Not Enrolled |

||||

|

Yes |

1,914.5 |

1,180.0 |

3,534.1 |

6,628.6 |

|

No or independent |

716.9 |

9,343.8 |

934.6 |

10,995.3 |

|

Attend Institution in State of Legal Residence |

||||

|

Yes |

1,900.4 |

9,488.0 |

4,254.4 |

15,642.8 |

|

No |

677.8 |

858.7 |

153.4 |

1,689.9 |

|

Foreign or international student |

53.6 |

176.7 |

60.9 |

291.2 |

|

Institution Distance from Home (miles) |

||||

|

0–30 |

605.3 |

7,492.1 |

3,888.1 |

11,985.5 |

|

30–100 |

745.5 |

1,567.3 |

442.2 |

2,754.9 |

|

100-500 |

946.5 |

989.1 |

82.7 |

2,018.3 |

|

More than 500 |

311.3 |

407.2 |

42.4 |

760.9 |

|

Total |

2,631.5 |

10,524.3 |

4,468.1 |

17,623.9 |

|

NOTES: Cell counts calculated from row-wise weighted population estimates (in thousands). Tabulations exclude students who attended more than one institution during the 2003–2004 academic year. SOURCE: Data from National Center for Education Statistics, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, 2004 Undergraduates. Tabulation from DAS-T Online, accessed through http://nces.ed.gov/das/. |

||||

Census Schedule Versus School Schedule

Depending on the academic calendar at particular schools and the calendar structure (e.g., semesters or quarters), the peak of decennial census enumeration activity may coincide with particularly bad times to obtain an on-campus count: spring break or a change in term. Moreover, nonresponse follow-up activities can begin in earnest at the time that the school year winds down and students either graduate or return home. Later still, postenumeration surveys to assess coverage may occur when students are absent from the college location. (The short-term population shifts associated with college students’ spring break is also discussed briefly in Section 4–A.1.)

3–B.2

Boarding Schools

Boarding and preparatory schools pose the same basic issues and challenges to enumeration as colleges and universities. They also conform to an academic calendar and can be largely vacant during the summer months. Likewise, not all boarding school students actually live on school grounds, as some boarding schools take “day students” who live in the area and only come to school for classes. However, boarding school students differ from college students significantly in their age: because boarding school students are minors, they are legally and financially dependent on their parents and are almost certain to return to their family homes when school is not in session. Moreover, given the students’ youth, parents’ instinctive urge to count them at home is perhaps stronger than for older college students.

Data from the National Center for Education Statistics suggest that the total enrollment at boarding schools in the United States is approximately 100,000 students at 1,500 schools, including both day and boarding students.8 As of 2003, the Bureau of Indian Affairs operated 66 boarding schools with approximately 9,500 students; some of these students are known to live at the school location year-round, staying with a state- or tribe-appointed guardian during vacations (U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, 2004).

In the 2000 census, Rule 7 of the formal residence rules said that “a student attending school away from home, below the college level, such as a boarding school or a Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school” should be counted at the parental home. Accordingly, it stands as a key exception to a strictly applied “usual residence” concept. The Census Bureau’s internal committee that formulated the rules for 2000 elected to count boarding school students at home due to the “inherent dependency that boarding school students have on

their parents;” the analysts worried about accurately operationalizing a count of boarding students at the school because “there would most certainly be a greater possibility of misreporting if we were to leave the enumeration of this population to the students themselves or to school administrators” (Rolark, 1995:6). That said, boarding schools were not specifically mentioned in the include/exclude instructions at the beginning of the 2000 census questionnaire. If respondents (parents) strictly followed the questionnaire guidance, the advisory to exclude “people who live or stay at another place most of the time” would lead them to exclude boarding school students, even though the formal rule is to count them at home.

Other commentators who have looked at recent census residence rules (Lowry, 1987; Hill, 1987; Mann, 1987; Sweet, 1987) have advocated that the rule be changed to count students at the boarding school location, for consistency with true “usual residence.”9 Reflecting the desire for consistency, the Census Bureau’s draft discussion points on rules for the 2006 census test (shared with the panel) suggested that boarding school students be counted at the school location, not at the parental location, for consistency with “usual residence” (U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, 2004).

3–C

HEALTH CARE FACILITIES

Another major class of group quarters are those that provide health care and related services. Of particular interest in the census context are long-term care facilities, such as nursing homes and other residential communities for senior citizens, although health care settings where potential ambiguity in defining residence may occur include hospitals and rehabilitation and treatment centers. Health care-related group quarters are sufficiently varied, and living situations so potentially complex, that 4 of the 31 formal residence rules for the 2000 census dealt explicitly with them. Rule 3 says that a person who “lives in this household, but is in a general or Veterans Affairs hospital on Census Day,” should be counted at “this household, unless in a psychiatric or chronic disease hospital ward, or a hospital or ward for the mentally retarded, the physically handicapped, or drug/alcohol abuse patients. If so, the person should be counted in the hospital.” Rules 21 and 23 indicate that persons who are, on Census Day, “under formally authorized, supervised care or custody,” in a “nursing, convalescent, or rest home for the aged and dependent” or a “home, school, hospital, or ward for the physically handicapped, mentally re-

tarded, or mentally ill,” are to be counted at the facility. Likewise, Rule 24 indicates that persons at emergency or other shelters on Census Day should be counted at the shelter.

As shown in Table 3-1, the 2000 census tallied 1,720,500 people in nursing homes. It included in its “institutionalized” count 234,241 people in hospitals and other health care facilities (including schools for the handicapped), the largest share of which (79,106) were in mental (psychiatric) hospitals or wards. Group homes, including those connected to drug abuse recovery programs and homes for the mentally ill or disabled, accounted for 454,055 of the noninstitutionalized population.

The distinction drawn in the census tabulations between institutionalized and noninstitutionalized health service facilities is a telling one, because it speaks to what has been pointed out as a problem in the Bureau’s current handling of these types of group quarters. An important trend that has emerged over the past decade is a blurring of distinction between medical care facilities and what might ordinarily be considered an institutional group quarter. In the past, nursing homes were typically inhabited by long-term residents needing care and supervision, with some people staying at the facility for a 30-day-or-less rehabilitation stay after a hospital procedure. More contemporary practice in health care suggests at least a three-level hierarchy in the type of care needed by sick and elderly patients:

-

residential care for persons who are physically capable of maintaining a large measure of independence in day-to-day living but who do require some level of assistance;

-

intermediate care for persons with conditions that render them unable to live independently, but not to the point that they need constant intensive care (instead, for example, they may need rehabilitation therapy to regain daily living functions); and

-

skilled care for persons who need constant attention from nursing personnel.

To satisfy these care needs, providers have developed an array of living settings and situations. McCormick and Chulis (2003:143) observe that the “proliferation of facility-like residential alternatives to nursing homes”—going by “various names including assisted living facilities, continuing care facilities, retirement communities, staged living communities, age-limited communities”—over the past 10 to 15 years is a major reason why 1980s-era projections of looming shortages of traditional nursing home beds “did not materialize.” These “life care communities,” which McCormick and Chulis (2003:143) dub elderly group residential arrangements, have added to the complexity in defining residence.

Some “life care communities” have three levels of care and housing. One level consists of people in independent living facilities, usually an apartment that they own or rent. Staff may come in to assist with some housekeeping tasks and the residents can cook for themselves or eat in a central restaurant. In the second level, assisted living, people still live independently, but they require more assistance with daily activities. The third level is for people unable to care for themselves and that need continuous daily care and supervision. Yet all three groups may live on the same campus under the same auspices. Are all of these people to be counted as institutionalized populations?

At the same time that health care services have diversified the type of housing and care options available to a longer lived (and longer active) elder population, the levels and types of care provided at hospitals—usually thought of as acute, short-term care facilities—has also changed in important respects. As health care providers have become more vertically and horizontally integrated, the physical structure that used to be only a “hospital” may now include such components as nursing home care, substance abuse treatment, psychiatric care, physical rehabilitation, and assisted living in separate wings (Drabek, 2005). Many hospitals offer extended care units (ECUs), which can offer home-like settings for lengthy periods of time while still permitting 24-hour observation and care. These ECUs are often connected to psychiatric services provided for both adult and adolescent patients, but can be more general; extended-term rehabilitation and nursing units may be embedded in a hospital system (and indeed within hospital buildings). Still other hospitals have cited the cost and liability of maintaining ECUs and have dissolved them, transferring patients to dedicated facilities elsewhere.

A series of surveys conducted by the Census Bureau on behalf of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) offers empirical evidence of some of the dynamics of the long-term care population. Since 1973, NCHS has periodically contracted with the Census Bureau to conduct the National Nursing Home Surveys (NNHS).10 In the most recent round for which data are available (1999), a sample of 1,500 facilities was drawn, each was mailed an advance letter, and an interviewer set up an appointment with the administrator. The interviewer administered a questionnaire on facility characteristics to the administrator. They then asked for a list of both current residents and residents who had been discharged during a specified month (one chosen between October 1998 and September 1999); up to six current residents and six discharged patients were randomly selected from these rosters. No resident—current or discharged—was interviewed directly; instead, the interviewer collected information from facility staff members suggested by the

|

10 |

NNHS rounds were fielded in 1973–1974, 1977, 1985, 1995, 1997, and 1999; a new version was to be fielded in late 2004, but data from that round have not been released. See http://www. cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nnhsd/nnhsdesc.htm [8/1/06]. |

administrator. The current patient questionnaire11 directs the interviewers to ask the staff member if they have the medical file and records for the selected patient; “if no record is available for a resident, try to obtain as much information as possible from whatever administrative records are available and/or from the respondent’s memory.”

Analyzing data from the 1977, 1985, and 1999 NNHS rounds, Decker (2005) estimates that the total number of residents receiving care at nursing facilities in 1999 was 1.63 million, a 27 percent increase from 1977; these were distributed across 18,000 facilities. However, this growth in total residents served was accompanied by a higher rate of discharge and shorter lengths of stay. The number of discharges per 100 nursing home beds grew from 86 and 77 in 1977 and 1985, respectively, to 134 in 1999. This escalation in the discharge rate was concentrated almost entirely among cases in which the patient’s length of stay was less than 3 months; see Table 3-3. The growth in short-term stays resulted in an overall drop in the mean length of stay from 398 days in 1985 to 272 days in 1999. Decker (2005:3) comments that “the increase in the number of nursing home residents requiring short stays co-incides with the implementation in 1983 of the hospital prospective payment system. This system shortened hospital stays and increased Medicare-funded postacute care in nursing homes.”

Still, “the nursing facility was in 1999, as it was in 1977, a place where many of the residents had been in the facility for substantial durations since their admission”—27 percent of current residents in 1999 had been in the facility for 3 years or more since admission, and 30 percent had stays of 1–3 years (see Table 3-3) (Decker, 2005:3–4).

A second survey covering part of the long-term care population—specifically, transitions between short-term hospitalization and long-term care—is the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS). Every year since 1965, the NHDS has examined the characteristics of inpatients discharged from non-Federal short-stay hospitals, based on sample of approximately 270,000 patient records across about 500 hospitals. Only hospitals with an average length of stay of less than 30 days are eligible for inclusion in the sample. The NHDS collects data from a sample acquired in two ways—manual transcription from hospital records to survey forms, by hospital staff or by Census Bureau staff (on NCHS’ behalf) or through purchase of electronic medical records data. Analysis of data from the NHDS (Kozak, 2002) shows 2.8 million transfers of patients from hospitals to long-term care institutions in 1999, up from 1.6 million in 1990. These transferred patients tended to have had shorter hospital stays in 1999 than in 1990: nearly half stayed in the hospital 5 days or less in 1999. Kozak (2002) concludes that these trends

|

11 |

The questionnaire is viewable at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nnhsd/nnhs99_3.pdf [8/1/06]. |

Table 3-3 Patient Discharges and Distribution of Current Nursing Home Residents, by Length of Stay (in percent)

|

Length of Stay |

1977 |

1985 |

1999 |

|

Patient Discharges per 100 Beds |

|||

|

Less than 3 months |

46.1 |

40.3 |

91.7 |

|

3 months to less than 1 year |

19.3 |

17.2 |

20.0 |

|

1 year to less than 3 years |

12.0 |

11.6 |

12.5 |

|

3 years or more |

8.7 |

8.5 |

10.0 |

|

Percent Distribution of Current Residents |

|||

|

Less than 3 months |

14.4 |

12.8 |

17.8 |

|

3 months to less than 1 year |

22.1 |

23.9 |

25.0 |

|

1 year to less than 3 years |

32.8 |

31.4 |

30.1 |

|

3 years or more |

30.7 |

31.9 |

27.1 |

|

SOURCE: Decker (2005:Figures 3 and 4), from National Nursing Homes Surveys, 1977, 1985, and 1999. |

|||

suggest that skilled, subacute care in long-term care facilities is increasingly a substitute for hospital care.

Thus, overall, trends in the industry make it difficult to accurately develop address lists for health care facilities, and the internal diversity in living situations in facilities labeled “hospitals” or “nursing homes” exacerbate the problem. Address listing efforts that rely on the name of an institution, or the classification derived from state licensing regulations, may be out of step with the specific unit-by-unit duration of stay and level of care or oversight provided in the facility. For example, the unit occupied by “a person with Alzheimer’s [disease] who lives in a residential care setting that provides 24 hour, 7 day a week oversight could be counted as residing in a non-family housing unit, an institutional setting, or a [group quarters] non-institutional setting depending upon the name of the place (assisted living, nursing home or group home, respectively)” in which the unit is nested (Drabek, 2005:1).

Noting this limitation of facility-based analysis, McCormick and Chulis (2003:143) pursued another route by analyzing the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, whose sample of respondents is drawn from the Medicare Enrollment Files (person-based), and thus can be contacted wherever they are found. The authors estimate that 30 percent of Medicare recipients living in long-term care facilities lived in elder group residential arrangements in 2001, a near doubling from the 16 percent estimated in 1996; the percentage living in Medicare- or Medicaid-certified nursing homes (institutional) dropped from 70 percent in 1996 to 59 percent in 2001 (McCormick and Chulis, 2003:144).

In addition to the problems associated with simply constructing a list of the units in health care group quarters are the no-less-tricky concerns of collecting information from their patients, once and only once:

-

Within the facilities, people’s willingness and basic capability to respond to a census questionnaire can vary greatly; for the sake of patients under care and to ease disruption, then, facility administrators bar direct access to patients in many cases. In the 2000 census, just 5 percent of people counted in nursing homes responded to the census questionnaire on their own, and only 8.8 percent of those in hospitals responded on their own; administrative records were used to fill in information on 72.8 and 65.8 percent of those groups, respectively (see Chapter 7 and Table 7-1).

-

Much as is the case with college students or on-duty military personnel, the family members remaining at a household when a loved one enters a hospital or nursing facility may not think of the facility as their loved one’s “usual residence.” This is particularly the case if the move is seen as limited in term (e.g., physical rehabilitation) rather than long-term care.

3–D

CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES

As shown in Table 3-1, the 2000 census counted nearly 2 million people at correctional facilities of some sort; about 55 percent of that total was recorded in state prisons. The vast majority of the incarcerated population is housed in prisons or jails, which differ principally in the expected length of stay. Sickmund (2004:20) distinguishes between the two types of facilities:

-

Prisons “are generally state or federal facilities used to incarcerate offenders convicted in criminal court. The convicted population usually consists of felons sentenced to more than a year.”

-

Jails “are generally local correctional facilities used to incarcerate both persons detained pending adjudication and adjudicated/convicted offenders. The convicted population usually consists of misdemeanants sentenced to a year or less. Under certain circumstances, they may hold juveniles awaiting juvenile court hearings.”

The number of persons actually incarcerated in prisons or jails is a relatively small part of the overall population in the criminal justice system. “Of all offenders under correctional care on any given day, nearly three-fourths are under some form of community supervision” (Clear and Terry, 2000:517), which is to say probation or parole arrangements.

Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) tabulations of the correctional population at the end of calendar year 2004 put the total incarcerated population at

2,267,787 (Harrison and Beck, 2005). Of these, 1,421,911 were housed in federal and state prisons and 713,990 in local jails (15,757 were housed in prisons in U.S. territories). In addition, 9,788 were housed in facilities maintained by the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement and 2,177 in military disciplinary facilities. Estimated population counts were available for slightly different time vintages for two other groups, those in Indian tribal jails (1,826 as of midyear 2003) and in juvenile correctional facilities (102,338 as of October 2002).

Federal prisoners constitute a small share of the overall prison count; as of December 8, 2005, weekly population data from the Federal Bureau of Prisons12 indicated 188,288 federal inmates total. Of these, 85 percent were housed in prisons maintained by the Bureau of Prisons, 10 percent in privately managed secure facilities, and 5 percent in community correction settings (most of these in designated halfway houses or community correction centers).

The incarcerated population shares many of the same challenging features as other institutional group quarters, but in most respects the conceptual problems they raise are even more complicated. Prisoners are arguably tied to more than one residence location and yet defining them as resident of any location is troublesome. They do not—and cannot—live day-to-day in the communities from which they were sent to prison, and yet their possible eventual return creates demands for such local services as parole monitoring, substance abuse rehabilitation, and job counseling social services. They also do not live day-to-day in the communities in which the prisons are located, in that they do not drive on the roads or use other services. Yet they may be counted in those locations for purposes of legislative representation—even though they may be prohibited from voting for said representatives. Like the other institutional group quarters, prisoners may also have family members “back home” who may be reluctant to exclude them from a household count; alternatively, the stigma of incarceration may lead family members to sever ties with the convicted.

Given their size relative to other categories, we focus in this discussion on prisons and jails. However, we note that non- or semi-incarcerative correctional programs may have residential components and so can present challenges to accurate counting. “Halfway houses” or community correctional centers provide room and board (and possibly other services, such as counseling) for those reentering society after serving their sentences; depending on sentence and parole terms, prisoners may spend up to 1 year (and sometimes more) during the transition from prison to society. Work-study release centers typically “allow a person to be free during working hours in order obtain or keep a job but require a return to the facility overnight” (either a local

|

12 |

See http://www.bop.gov/locations/weekly_report.jsp [12/8/05]. |

jail or other location); “boot camp” facilities put inmates through a short-term (90–180-day) quasi-military program to instill discipline, while “shock probation” sentencing arrangements can pair a short-term incarceration with a probationary period (with the intent of deterring future criminal activity) (Clear and Terry, 2000:518–519).

3–D.1

Prisons

Rules and procedures for counting prisoners have been a long-standing concern in the census. The enumerator instructions for the 1850 census were the first to discuss the issue directly, stipulating that “all landlords, jailors, [and superintendents of institutions] are to be considered as heads of their respective families, and the inmates under their care to be registered as members thereof,” with “convict” status noted in another column (Gauthier, 2002:10–11).13 The census schedule (enumerator form) further directed that “the crime for which each inmate is confined, and of which each person was convicted,” be recorded, but urges that information on recent prison releases might best be gathered by reference to administrative records:

When persons who had been convicted of crime within the year reside in families on [Census Day], the fact should be stated, as in the other cases of criminals; but as the interrogatory might give offence, the assistants had better refer to the county record for information on this head, and not make the inquiry of any family. With the county record and his own knowledge he can seldom err.

Similar procedures held through 1880; the 1890 census still considered inhabitants of a prison as a family but directed that prisoners be listed on a separate schedule from the warden or other resident staff.

The 1900 census included a special schedule (enumerator form) for questions on crime. The instructions for that schedule made the first mention in census materials of the ambiguity of prisoners’ residence—“many prisoners are incarcerated in a state or county of which they are not permanent residents. In every case, therefore, enter the name of the county and state in which the prisoner is known, or claims, to reside.” In the main census schedule, enumerator instructions read that “all inmates of … institutions are to be enumerated; but if they have some other permanent place of residence,

write it in the margin of the [population] schedule on the left-hand side of the page.” No such provision was made in 1910 or subsequent censuses, and the practice of counting prisoners at the institutional location was adopted. Accordingly, rule 20 of the 2000 census residence rules indicated that a person “under formally authorized, supervised care or custody, in a correctional institution, such as a federal or state prison” should be counted at the prison, with no provision made to claim a usual home elsewhere.

The Census Bureau has long argued that considering the prison the “usual residence” of an incarcerated person is a reasonable choice, and that other interpretations would raise further problems. Testifying before Congress in 1999, Census Bureau director Kenneth Prewitt summarized the Bureau’s major arguments, suggesting that creating an exception to usual residence for prisoners “may open a Pandora’s box of pressures for other exceptions to our residence rules” (U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Government Reform, 2000).14 Subsequently, the Bureau has continued to evoke the “Pandora’s box” argument in justifying its position on prisoner counting; for instance, commenting in a Texas newspaper article in late 2005, a census official noted that, in changing the rule, “you open up a Pandora’s box, a free-for-all census, where there’s no principle for where people are counted” (Price, 2005).15

Five years later, former director Prewitt took the opposite stance on prisoner counting, writing in a foreword to a Brennan Center for Justice report that “changes in the criminal justice system over the last three decades call into question the fairness of counting persons where they are imprisoned” and that “current census residency rules ignore the reality of prison life.” “Counting people in prison as residents of their home communities offers a more accurate picture of the size, demographics, and needs of our nation’s communities,” he continued, “and will lead to more informed policies and a more just distribution of public funds” (Allard and Levingston, 2004).

What makes the issue of prisoner counting in the census a significant one, empirically, is a major sociological trend—namely, the major growth in the incarcerated population since the mid-1970s through 1990s, following decades of remarkable stability in the incarceration rate from 1925 to 1975 (for reviews, see, e.g., Blumstein, 1995; Cullen and Sundt, 2000; King, 1998; Zimring and Hawkins, 1991). Analysts from the Brennan Center for Justice at New

York University School of Law summarize this expansion by noting that the incarcerated population grew fourfold between 1980 and 2002, from about 500,000 to more than 2 million people (Allard et al., 2004).

Prisoner counting in the census is especially controversial (and will likely remain so) because it lies at the intersection of two of the most potent and enduring social struggles in the American experience: race and the urban-rural divide. The incarcerated population is markedly different from the general population in that it is more than 90 percent male and includes a disproportionate share of racial minorities. Using 1998-vintage estimates, Cullen and Sundt (2000:483) found that blacks represent 12.7 percent of the general population, compared with 41.3 percent of the state and federal prison population. Lotke and Wagner (2004:593–594) find that “nearly 9% of all African American men in their twenties and thirties live in prison.”

The second core political tension at the heart of the prisoner counting issue is the tension between urban and rural areas for equitable shares of representation and resources. Prisons are frequently sited in rural areas rather than large urban centers. “[Prisoners] are not generally from the county where the census has them placed,” note Lotke and Wagner (2004:592); “they were imported from other counties for purposes of confinement” and “if the [prison] doors were opened, few would stay” in the vicinity of the prison. For example, Heyer and Wagner (2004) estimate that 99 percent of Illinois’ prison cells are not located in Cook County (Chicago), although 60 percent of the state’s prisoners come from the county, and Los Angeles County, California, is the source of 34 percent of the state’s prisoners, but only 3 percent of the state’s prison population is housed there. Similar arguments can be made for other urban centers; notably, Philadelphia (which functions jointly as a city and a county) “is the legal residence for 40 [percent] of Pennsylvania’s prisoners, but the County contains no state prisons.” In comparison with the general population, Allard and Levingston (2004) suggest that 40 percent of incarcerated persons nationwide are in rural facilities, while rural residents make up 20 percent of the U.S. population.

As a share of the total U.S. population, prisoners (like the rest of the group quarters population) are a relatively small group, but at the local level prisons can be very significant. Lotke and Wagner (2004:603) cite the extreme example of Florence, Arizona, which “has a free population of roughly 5,000 plus another 12,000 living under lock and key,” as it is the location of four prisons.16 Six state prisons are located in Gatesville, Texas, and about 58 percent of Gatesville’s 2000 census population of 15,591 were listed as coming from institutional group quarters. Moreover, all but one of the Gatesville facili-

ties are female only, heavily skewing the city’s overall demographic portrait.17 More generally, Lotke and Wagner (2004) observe that 197 counties out of 3,141 (6.3 percent) have more than 5 percent of their population in prison. Eighteen counties (13 of which have majority rural populations) have more than 20 percent of their population in prison. Heyer and Wagner (2004) observed that 56 counties that reported growth during the 1990s (comparing the 2000 census to 1990) would have actually posted declining populations, save for the addition of new prison beds to their jurisdictions.

A major use of decennial census data is for allocation of state and federal funds: such allocations—and whether the monies should be directed at the communities housing prisons or those which prisoners leave and reenter—are a source of much contention. “Where prisoners are counted—in penitentiaries usually in remote areas far from home—effectively shifts political power, taking federal and state dollars, and social services, from urban areas to rural ones” (Price, 2005): hence, it could be argued that this shift “skews a state’s public policy agenda.” Analyzing 1992–1994 data, Beale (1996:25) found that 60 percent of new prison construction is in rural, nonmetropolitan counties, even though those counties account for only 20 percent of the national population; he concluded that, “whether through unsought placement of facilities or aggressive local bidding for them, prison construction and employment have become economically important for many rural areas.” The potential effects on available revenues associated with prison location can be major. For Florence, Arizona, Lotke and Wagner (2004:603) estimate the influx of annual funds tied to the various prison facilities at $4 million; other state and local funds account for $1.8 million, and local measures produce $2.3 million.18

Arguments about the fairness of fund allocations, and the influence of prisoner counts on them, can be made by both the source and destination communities of prisoners. Proponents of change to the Census Bureau’s current policy of counting prisoners at the facilities argue that the policy disadvantages prisoners’ home communities by denying them resources they need to facilitate effective prisoner reentry to the community (e.g., occupational

counseling, substance abuse treatment) and prevent recidivism. It is these “home communities,” the argument follows, that educational and transportation systems will have to meet the needs of returning prisoner populations; by nature of their confinement, prisoners do not use those resources in the prison host community. Acknowledging that the prison site “may lose some formula funding for water or sewerage,” proponents of a change in counting rules for prisoners suggest that these costs could be recouped in other ways, including revised contracts with state governments and departments of correction (Lotke and Wagner, 2004:606).

However, prison sites argue just as vigorously that they need the resources due to the large immediate burden placed on them by prisoner. For instance, the city of Pendleton, Oregon, “receives around $35,000 a year from the state’s liquor and cigarette taxes and 9-1-1 fees” and “about $75,000 annually from the state’s gas tax,” all based on residency counts. These figures are swayed in part by the location of the 1,600-inmate Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution in the city. Local officials concede that the inmates are not active participants in the community, but they argue that additional funds are justified by the demands on city water, sewer, and gas services by the prison, as well as city fire and police emergency response (East Oregonian and Associated Press, 2006).19

Two federal court precedents are central to the current Census Bureau handling of prisoners in the census. We discussed the Third Circuit Court of Appeals’ 1971 ruling in Borough of Bethel Park v. Stans in Box 3-2. The Bethel Park plaintiffs claimed that institutionalized persons (including prisoners) were one of three major groups that were misallocated under the Bureau’s residence rules. The Bethel Park court concluded that counting “persons confined to institutions where individuals usually stay for long periods of time as residents of the state where they are confined … has a rational basis.” Thirty years later, the counting of prisoners in the census was directly challenged by the District of Columbia, which then housed all of its felony prisoners at the Lorton Correctional Complex in Virginia. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia held that the Census Bureau is not compelled to consider factors like the impact of residence rule determinations on fund allocation; they are required to make a “rational determination” in defining residence, and the court judged that the Bureau’s policy of counting the prisoners in Virginia had a rational basis. Box 3-3 summarizes the case in more detail.

In the rest of this section, we consider the major threads of argument that have been advanced concerning whether prisoners should be counted at prison or at some other location.

Implications for Districting—The Potential for Intrastate Distortion

A fundamental use of census data is for the construction of congressional and state legislative districts. Regardless of where they are counted, prisoners present an immediate complication for this use of census data. Only two states permit prisoners to vote during their periods of incarceration, but all prisoners count toward the composition of districts—for purposes of ensuring equal district population size.20 This source of distortion is compounded by the size and general location of correctional facilities; particularly for state legislative districts, the siting of prisons in rural areas can draw representation away from urban centers.

Both the Prison Policy Initiative (see, e.g., Wagner, 2002; Heyer and Wagner, 2004; Lotke and Wagner, 2004)21 and the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law (Allard and Muller, 2004) offer clear and compelling empirical evidence of the distortion that can be induced by prisoner counts. Much of the work has focused on the state of New York, where prisons are generally located upstate while the majority of incarcerated persons come from the New York City area. Pendall (2003) found that the upstate New York region achieved only very mild population growth over the 1990s, but a large share of that was attributable to prisons; 30 percent of new “residents” to the upstate counties in the decade were prisoners. More anecdotally, Lotke and Wagner (2004) cite the admission of a New York state senator (whose upstate district includes six prisons) that “it’s a good thing his captive constituents can’t vote, because if they could, ‘They would never vote for me.’ ”

As a result, Lotke and Wagner (2004:593–594) argue that the incarcerated population—including the “nearly 9% of all African American men in their twenties and thirties” who are imprisoned—“[are] apportioned to legislative districts that do not reflect their communities of interest or their personal political concerns. Whether they can or do vote is irrelevant; their bodies still count in the prison district. A more refined analysis shows that the impact is modest in U.S. Congressional Districts but more significant in state legislative districts.”

|

20 |

It should be noted that distortion in voting influence may also arise because the population counts used to determine district size include other large population segments that do not have the right to vote, most notably, children under voting age and noncitizens. In addition, population counts also include those people who choose not to vote or register to vote. |

|

21 |

See also the state-level analyses posted at http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/impact. shtml [8/1/06]. |

|

Box 3-3 District of Columbia v. U.S. Department of Commerce (1992) In November 2001—pursuant to congressional legislation enacted in 1997—the Lorton Correctional Complex in Northern Virginia’s Fairfax County ceased operations. The facility’s closure ended nearly 90 years of a unique arrangement, in that the Lorton facility was purchased at the direction of Congress to house felony prisoners from the District of Columbia; though located in Virginia, the complex was operated and managed by the District of Columbia Department of Corrections. The unique situation at Lorton occasioned a challenge to the 1990 census, with the potential of setting a precedent for the counting of prisoners housed out of their home state. Specifically, the District of Columbia filed suit against the U.S. Department of Commerce and the Census Bureau, arguing that the Bureau’s “inclusion of Lorton Correctional Facility inmates in the 1990 Census as residents of Virginia rather than of the District of Columbia violates the Constitution and the Census Act,” a decision which the District alleged would mean a loss of $60 million in federal fund allocations over the 1990s. In particular, the District cited the unique ceding of Virginia land by Congress for purposes of housing District of Columbia prisoners as support for counting Lorton prisoners in the District. The Census Bureau countered that “the Bureau’s application of the usual residence rule to Lorton inmates is a rational decision that is not arbitrary and capricious,” that the counting of Lorton prisoners in Virginia was consistent with the definition of usual residence, and that Lorton inmates had been counted as Virginia residents since the opening of the prison in 1916. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled on District of Columbia v. U.S. Department of Commerce (789 F.Supp. 1179) in April 1992. The court was unconvinced that Lorton’s management by the District of Columbia should have any impact on where its residents are counted. “Retention of control and management, despite United States ownership, does not automatically qualify a property as ‘unique’ such that it deserves different rules for the Census enumeration;” all federal prisons which hold inmates from outside the state where the prison is located are subject to the same arguments, as are military installations. That said, the court observed that the District of Columbia did make a solid point when arguing that the District “pays all of the costs of maintaining Lorton, including water and electricity,” and that inmates retained eligibility for “health, social and educational benefits” paid for the by District. In short, the District bore all costs for Lorton, while “Virginia’s only connection to the facility is that it is within the geographic boundaries of the state and Virginia can not collect taxes from businesses or residences that otherwise might have been there.” “In one light, this would appear to be a convincing argument,” the court held; indeed, “it appears that all that separates Lorton residents from being counted as District of Columbia residents is a mere vagary of the District of Columbia’s strange position as a city without a state.” However, the court concluded that the paramount goal of the census is the production of a count for the purposes of apportionment and that, “however rational it may seem to examine the source and nature of fiscal support” won or lost by residence definitions like the Lorton case, “the Census Bureau is not required to do so.” Rather, the court held that the Census Bureau’s interpretation of usual residence, “based on geography” and “developed and consistently applied,” constitutes a “rational determination.” In short, the court ruled that, “although including Lorton within the District of Columbia population may be more equitable, we cannot say that the Bureau acted without a rational basis. …The solution to the District’s problems lies not in adjusting the Census count, but in changing the way funds are distributed.” |

|

(In a footnote, the court raised another problem with diverging from the usual residence rule: namely, the conceptual problems that would arise. “Where would inmates actually be counted, where they lived prior to incarceration? And then what of the current residents of that address? How would they be counted for representation purposes?”) After the closure of the Lorton Correctional Complex, prisoners housed there were to be transferred to facilities of the Federal Bureau of Prisons or to private correctional facilities. In most cases, these new transfer locations were substantially further away from the District of Columbia than Lorton. |

Custody Versus Jurisdiction

In a correctional setting, the distinction between the agency or location of jurisdiction (the one with legal responsibility for a prisoner) and the agency or location of custody (where the prisoner is actually housed) is an important one, because they are not always identical. The nature of incarceration is such that divergence in the locations of custody and jurisdiction creates the possibility for distortion in population counts, both across and within states.