7

Resources for the Drug Safety System

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) lacks the resources needed to accomplish its large and complex mission today, let alone to position itself for an increasingly challenging future. Despite the fact that so much has changed in drug discovery and development, in the number and complexity of FDA’s congressionally mandated responsibilities, in the practice of medicine, the structuring and delivery of health care, the way drugs are used, the role of patients and consumers, and the information environment, FDA appropriations for new drug review have remained roughly flat (in constant dollars) since the passing of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) (Thompson, 2000; GAO, 2002).1 User fees have led to an overall increase in resources for new drug review, but activities not funded by user fees have received a smaller portion of FDA’s total budget. There is little dispute that FDA in general is, and the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) specifically remains, severely underfunded (Goldhammer, 2005; Wolfe, 2006). There is widespread agreement that resources for postmarketing drug safety work are especially inadequate and that resource limitations have hobbled the agency’s ability to improve and expand this essential

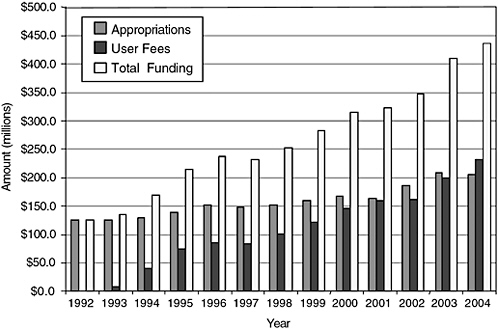

component of its mission. Continued resource shortages will impede the agency’s ability to use new and future scientific and technological advances in drug research across the lifecycle. In particular, the limited resources could impede the agency’s ability to detect risks of new drugs in a timely fashion, analyze emerging drug safety data, and effectively communicate that information to the public in the ways envisioned in the committee’s report. For fiscal year 2006, CDER’s enacted budget was $517,557,000, with $297,716,000 from congressional appropriations and $219,841,000 (or 42.5 percent of the total budget) from user fees (see Figures 7-1 and 7-2 for more information on trends in CDER funding and staffing).

Although PDUFA has facilitated substantial expansion of CDER staff, especially in the Office of New Drugs (OND), growth has been largely to shorten review times and improve related processes, including interactions with industry representatives and the development of guidances, rather than strategic with respect to the full breadth of functions and disciplines needed to operate the largest center of a world-class regulatory agency. PDUFA I and II did not allow for the use of PDUFA funds to support postmarketing drug safety work. PDUFA III allowed for a very restricted amount of funds to be used for very specific and narrow postmarketing safety work (postmarketing surveillance of drugs for 2–3 years after approval) (FDA,

FIGURE 7-1 History of CDER funding.

SOURCE: PDUFA White Paper (FDA, 2005b).

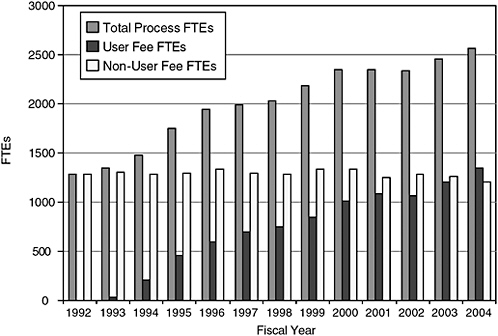

FIGURE 7-2 History of CDER staffing.

SOURCE: PDUFA White Paper (FDA, 2005b).

2003). These restrictions have contributed to a troubling resource imbalance between OND and other CDER units (e.g., postmarketing safety activities, compliance). Some effects or correlates of the resource imbalance between OND and the Office of Drug Safety (ODS)/ Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology (OSE) are discussed in Chapter 3.

The committee recognizes that the recommendations in this report come with a price tag, one that is most likely large and believes it would be ill-advised to expect CDER to take on the many new responsibilities called for in this report without new funds for strengthening the number and expertise of staff, for intramural and extramural research, and for information technology. On the other hand, the committee believes that full implementation of the recommendations it offers is essential. Although some of the recommendations are more far-reaching than others, the committee believes each of its recommendations will serve to improve the drug safety system.

For the past 15 years, user fees have supported a steadily increasing share of CDER’s work. Many have argued that relying so heavily on industry funds is inherently inappropriate and damaging to the reputation and functioning of CDER, indeed, of any regulatory entity. Some CDER staff, as well as some public advocates (Wolfe, 2006) have expressed discomfort with this funding (DHHS and OIG, 2003; GAO, 2006; IOM Staff Notes,

2005–2006; Union of Concerned Scientists, 2006) based on real or perceived “capture” of the agency, that is, that the center’s increasing dependence on industry funding in itself creates a sense of obligation “to please” on the part of the agency. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) itself has expressed a concern about this perception.

“We share a concern with FDA about the current balance between the user fee portion and the appropriated portion of the review process,” PhRMA’s Goldhammer says. As industry funding approaches half of the review budget, “it has led to a perceptual issue that industry is paying for the review process and that the American public, through its tax moneys, is not. We would hope that can be dealt with in some way because we don’t want there to be the perception that this is an industry-driven program” (Thompson, 2000).

The effects of user-fee funding are experienced differently by different staff at CDER (IOM Staff Notes, 2005–2006). Some staff recognize no impact on their day-to-day work of the source of their salary and support the principle and practice of the user-fee system, while others expressed concerns about the workload and time pressures that they feel have accompanied the PDUFA funding,2 cognizant that if industry were displeased with CDER performance and worked to eliminate user fees (and appropriations did not increase to close the shortfall), staff would have to be eliminated. Yet other CDER staff, particularly CDER leadership and managers, describe PDUFA as setting necessary performance goals that any responsible agency should employ regardless of links to funding source, and deny that the goals are used as anything more than targets. Indeed, the goals allow for review times longer than the 6- and 10-month approval targets in up to 10 percent of the cases for standard-rated and priority-rated new drug applications. However, if CDER were to consistently miss the goals for time-to-approval, the pharmaceutical industry would push for changes in PDUFA fees or other arrangements in the following round of negotiations. This reality would undoubtedly put pressure on CDER management to meet these targets.

For some staff and policy analysts, user-fee funding, combined with industry’s considerable role in shaping PDUFA-associated goals and expectations, further reinforces the perception that the industry has become a primary driver of the agency’s priorities and performance.3 The notion

|

2 |

As described in Chapter 2, some CDER new drug review staff assert that the workload pressures to meet PDUFA goals are compounded by industry submissions that are not well organized, submissions that come in on paper or with data that are not easily reanalyzed, or on suboptimal management by their direct supervisors or team leaders. Some of these CDER staff also reported that the biggest pressures come from 6-month priority approvals and not from standard applications, the goal for which is 10 months for approval. |

|

3 |

Zelenay has proposed eliminating the PDUFA sunset clause as a means to reduce the industry’s bargaining power (Zelenay, 2005). |

of “regulatory capture”4 has been employed to describe the state of affairs created or, more likely, exacerbated by the user-fee system,5 namely, that powerful industry interests control or strongly influence the regulatory agency’s decision making.

Some have argued that eliminating industry funding for regulatory review is in the best interest of the credibility of the drug safety system. Others have argued that industry receives a valuable service (timely approval of their products) and should be expected to pay for this,6 as long as agency independence and the credibility of its scientific review remain intact. Others argue that without extra funding from user-fee revenue, the delays in new drug review observed prior to user fees will return since FDA budgets will then be subject to fluctuations in the policitical climate and increased pressures to reduce government spending. This too may compromise the effectiveness of our drug approval system.

As described elsewhere in the report, PDUFA has included an extensive number of performance goals (see Appendix C for a complete listing). CDER reports yearly to Congress on how well it has met those goals (in the performance goals letter7 submitted by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), see, for example, http://www.fda.gov/cder/pdufa/default.htm). Along with performance goals, PDUFA includes restrictions on how CDER can use its funds. Each round of PDUFA negotiations has led to more demands on CDER and continued restrictions on CDER’s flexibility. The committee is not concerned about the existence of performance goals in principle,8 but finds the limitations or “strings” that direct how CDER can use PDUFA funds the most troubling aspect of the arrangement.9

7.1: To support improvements in drug safety and efficacy activities over a product’s lifecycle, the committee recommends that the Administration should request and Congress should approve sub-

|

4 |

Adapted from the capture theory of regulation advanced by Stigler (1971) and critiqued by Laffont and Tirole (1991) and by Carpenter and Ting (2004). |

|

5 |

The industry has a powerful influence on the political process and on the regulatory environment whether or not it funds the agency. |

|

6 |

Similar arguments have been made regarding user-fee programs for other regulatory agencies. |

|

7 |

http://energycommerce.house.gov/107/hearings/03062002Hearing502/print.htm. |

|

8 |

See Chapter 3 for a recommendation regarding institution of safety goals. |

|

9 |

The committee is aware that other regulatory agencies, for example the Environmental Protection Agency and the Federal Communications Commission, are supported in part by specific user-fee programs. Some user fees go directly into the Treasury; other user fees go to the agency and offset congressional appropriations. The committee has not done an exhaustive analysis of other user-fee programs but is of the understanding that they are not associated with significant requirements on how the agency uses the fees to achieve programmatic goals. |

stantially increased resources in both funds and personnel for the Food and Drug Administration.

The committee favors appropriations from general revenues, rather than user fees, to support the full spectrum of new drug safety responsibilities proposed in this report. This preference is based on the expectation that CDER will continue to review and approve drugs in a timely manner and that increasing attention to drug safety will not occur at the expense of efficacy reviews but rather it will complement efficacy review for a lifecycle approach to drugs. Congressional appropriations from general tax revenues are a mechanism by which the public can directly, fairly, and effectively invest in the FDA’s postmarket drug safety activities. However, if appropriations are not sufficient to fund these activities and user fees are required, Congress should greatly reduce current restrictions on how CDER uses PDUFA funds. Should the sources described above be insufficient, alternatives that could be considered and evaluated by Congress include but are likely not limited to a user fee associated with the consumption of prescription medications and a sales tax on purchase of marketing services by pharmaceutical companies.

By some estimates, more than a billion prescriptions are written each year in the United States. A small tax on prescriptions could generate significant funding to implement the recommendations made in this report. A tax of ten cents on every prescription, for example, would generate more than $100 million for the FDA budget. The administrative costs of collecting such a tax would need to be considered as well as the ultimate incidence of the tax. For example, collecting the tax from retailers or consumers at the point of sale might have higher administrative costs than collecting it from manufacturers. On the other hand, manufacturers might not know how many prescriptions were filled out of a given amount of product sold to a wholesales or retailer. An alternative approach might be to tax manufacturers based on the value of sales (perhaps net of rebates). This would have the advantage of more heavily taxing more expensive drugs, which would tend to be the newest ones and the ones around which there is greatest uncertainty about safety. Regardless of the taxation method used, it must be considered that the ultimate incidence of the tax will be on consumers and will be regressive. This tax would likely also have an effect on the costs of and access to pharmaceuticals.

Another tax-based proposal would seek to accomplish two goals—revenue enhancement and deterrence of excessive DTC advertising. A direct tax on DTC advertising for newer drugs would have the advantage of linking the decision to impose a tax with the finding that newer drugs necessarily suffer from greater uncertainty with respect to safety and efficacy in the general population, which is more heterogeneous than that studied in the

preapproval clinical trials. On the other hand, taxation of protected speech can raise constitutional objections that have yet to be fully litigated before the courts. An alternative is to deny the tax deductibility of pharmaceutical advertising. Just such a proposal was made in H.R. 1655: America Rx Act, although in that case the resulting revenues were to be used to offer discounts on prescription drugs to those in need.

Regardless of the source of the funds, the committee reiterates that the functioning of a drug safety system that assesses a drug’s risks and benefits throughout its lifecycle is too important a public health need to continue to be underfunded.

The committee was charged with reviewing CDER’s resources but concluded that it was not feasible to do a financial audit of CDER or a detailed calculation of the costs for CDER or other stakeholders, including the pharmaceutical industry, of implementing the recommendations in this report. Convention dictates that federal agencies do not publicly articulate resource needs that differ from those offered in the President’s budget, so the committee was unable to understand fully what CDER and FDA leadership estimate is needed to meet current objectives, let alone the expanded responsibilities the committee envisions for the future. Thus, the committee can only offer general guidance and estimates of resources that will be required to implement its recommendations; it does so with the caveat that this list is most likely incomplete and is but a starting point for discussions between FDA and congressional appropriations committees. CDER will need carefully to assess their resource needs in light of the recommendations in this report.

Staff: The first three 5-year cycles of PDUFA funding and accompanying process improvements have led to dramatic shortening of the time required for new drug approval, in great part due to the significant staff increases, primarily in OND. The committee asserts that the next phase of improvements, including staff increases, should focus on the postmarket activities recommended in this report.

The committee notes certain facts about current staffing. CDER estimated that in 2004 it devoted 700 full-time equivalents (FTEs) for premarket safety work and 393 FTEs (or 36 percent of total safety-related FTEs) for postmarket safety work (FDA, 2005a,b). PDUFA funding supported 1320 FTEs for new drug review in 2004 and appropriations supported 1287 FTEs (FDA, 2005a,b). CDER staff devoted to new drug review has approximately doubled in the PDUFA era. Between 1996 and 2004, new drug review FTEs supported by PDUFA increased by 125 percent (from 600 to 1320) whereas ODS staff increased by 75 percent (from 52 to 90)10 (FDA, 2005a,b).

The committee recognizes that CDER will require a significant increase

in staff to meet the new responsibilities described in this report. CDER will require new staff, for example, to participate more actively in efforts to generate more and better safety analyses, such as through an expanded epidemiology contracts program; participate in new drug review teams; develop more consistent approaches to risk-benefit assessment both premarket and postmarket; evaluate risk minimization action plans; work with other federal agencies and departments in their efforts to improve their drug safety-related activities; evaluate industry-submitted 5-year reviews; routinely assess and make public emerging safety and effectiveness information, and consider appropriate imposition of the newly clarified conditions on distribution. The committee’s recommendations will require additional staff throughout CDER and with varied expertise, for example, epidemiology, statistics, public health, medicine, pharmacy, informatics, programming, law, regulatory policy, communication, as well as project management and administration.

The committee recognizes that increases in postmarket safety staff must be phased in over time. As CDER begins to implement the recommendations in this report and gradually increase their staff, the size of the needed increase will become apparent to CDER and the Congress. Congress can ensure this by requesting that CDER perform and make publicly available a formal evaluation of staff needs, perhaps in the form of a work audit. The FDA commissioner can serve an important role as a champion within the government and in discussions with Congress for needed resources. The committee also recognizes that other federal partners in drug safety will require additional staff to achieve a fully functioning postmarket drug safety system, as described in Chapter 4.

Research funds: ODS/OSE is the CDER component most likely to have primary responsibility for implementing the extramural and intramural research activities called for in the report. The committee was concerned by the very small and inadequate amount of funds for the epidemiology contracts programs in particular. CDER will also require funds for extramural contracts to improve their passive and active surveillance activities, in addition to increased intramural use of drug utilization databases and other datasets such as the General Practice Research Database.

The committee provides several estimates of needed funds for intramural and extramural research. The committee‘s lower bound estimate is that an expanded epidemiology contracts program would cost $10 million.11 The committee estimates that other agencies/departments also require similar resources for epidemiology research contracts. The committee offers as a

more ambitious estimate that the epidemiology contracts program at CDER should be expanded to $60 million.12 This upper bound estimate does not include the costs for research to be conducted by other DHHS agencies or other departments, such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The committee acknowledges that a financial investment will be required for the success of the public-private partnership (PPP) it recommends for the prioritization and planning of confirmatory drug safety and efficacy studies. The federal partners will require dedicated staff to make this partnership successful, in addition to research funds for studies. The committee anticipates that pharmaceutical companies and other health care industries will also fund some of this research.

The committee offers a lower bound estimate of $20 million per year for start-up and administrative costs of the PPP. This is based on an estimate for a research institute recently proposed to advance the Critical Path Initiative.13 As Chapter 4 describes, the PPP will have responsibility for prioritizing and planning postmarket studies to address public health concerns, will help advise on the design of such studies (including the postmarket study commitments agreed upon by CDER and industry), and will facilitate necessary collaborations between government agencies and departments, and the pharmaceutical industry. Some studies conducted under the aegis of the PPP will require new resources. Other studies will be ones likely done absent the PPP. In these cases the PPP brings added value to the research by advising on study design, but the conduct of the research itself will not require incremental funds.

An upper bound estimate for the PPP should include the cost of a large clinical trial. Although not all studies to be conducted under the aegis of the PPP are large, complicated, and expensive, some necessary studies will require significant new resources. The committee asserts that at least one major drug safety question that is best answered with prospective research of some magnitude could be addressed each year under the aegis of the PPP. Some of these studies would be epidemiology studies using existing data, such as those also conducted under the epidemiology contracts program. Other studies would address narrowly defined safety concerns in specific populations. As described in Chapter 4, some, if not most, of these studies would not be incremental costs to the system, because they would have occurred absent the PPP. However, it is not unreasonable to anticipate, and

it would be naïve to suggest otherwise, that on occasion significant new resources will be required to fund a large, prospective, randomized clinical trial to answer drug safety questions of pressing public health concern. Thus, an upper bound estimate of the resources needed for the PPP on such occasions is on the order of $150 million14 to be spread out over the period of time the study is conducted.

Information technology (IT): The committee concluded from its conversations with individual CDER staff that CDER’s IT systems are antiquated. Upgrades of staff workstations are clearly part of CDER and FDA plans, but there will be additional IT needs (e.g., servers, programmers, and training) to implement several of the recommendations in Chapter 4 that should be included in budget projections.

Other resource needs: The committee was tasked to assess only one aspect, drug safety, of CDER responsibilities. There are many important areas of CDER work that the committee did not assess, for example compliance, inspections, and the prevention of medication errors. The committee also realizes that the already-initiated PDUFA IV negotiations will likely result in additional requirements on CDER. The committee notes that both of these factors could very well require additional funds for staff and research.

It is critical that CDER assess the center’s resource needs with particular attention to ensuring that funding for premarketing product review and postmarketing risk-benefit assessments is commensurate with:

-

The breadth of both sets of programs and activities, and

-

Their importance in achieving a lifecycle approach to drug safety and efficacy that translates into how FDA regulates, studies, and communicates about drugs with stakeholders in industry, health care, academic research, and the public.

This process must be conducted with a keen awareness of the expectations, needs, and perspectives of all stakeholders in the system and in a transparent manner. It is incumbent on the leadership of the agency and the center, as well as the Administration, to present to Congress a full review and analysis of the levels of funding needed to fulfill the mission of the center and the vision the committee has set forth. While resources might not be immediately available, a public statement acknowledging the resource needs is essential.

FDA’s centennial offers an occasion to celebrate the past and to give serious consideration to what is needed to strengthen the agency’s central

role in assuring the safety and efficacy of prescription drugs now and in the future. Also, PDUFA reauthorization is just months away, and major legislation addressing drug regulation has been prepared and considered.15 These circumstances make this a golden moment of opportunity to improve fundamentally the way FDA regulation considers and responds to the evolving understanding of risks and benefits of drugs, and the way all stakeholders in the drug safety system perceive, study, and communicate about those risks and benefits. As described in Chapter 1, there have been many commissions and reports addressing issues similar to those contained in this report. It is the committee’s fervent hope that Congress, FDA, and the other stakeholders will seize the gathering momentum to invigorate the drug safety system. The agency’s credibility and its ability to protect and promote optimally the health of the American people cannot wait another year or another decade.

REFERENCES

Carpenter D, Ting MM. 2004. A Theory of Approval Regulation. [Online]. Available: http://people.hmdc.harvard.edu/~dcarpent/endosub-20040214.pdf [accessed October 10, 2005].

DHHS (Department of Health and Human Services), OIG (Office of Inspector General). 2003. FDA’s Review Process for New Drug Applications: a Management Review. OEI-01-01-00590. Washington, DC: OIG, FDA.

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). 2003. PDUFA III Five Year Plan. [Online]. Available: http://www.fda.gov/oc/pdufa3/2003plan/default.htm [accessed October 10, 2005].

FDA. 2005a. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research—Activities and Level of Effort Devoted to Drug Safety. Submitted to the Institute of Medicine Committee on the Assessment of the US Drug Safety System by FDA.

FDA. 2005b. White Paper, Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA): Adding Resources and Improving Performance in FDA Review of New Drug Applications. [Online]. Available: http://www.fda.gov/oc/pdufa/PDUFAWhitePaper.pdf [accessed December 5, 2005].

Federal News Service. 2000. Prepared Testimony of Richard Platt, MD, MSC, Professor of Ambulatory Care and Prevention Harvard Medical School Director of Research Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

GAO. 2002. Food and Drug Administration: Effect of User Fees on Drug Approval Times, Withdrawals, and Other Agency Activities. GAO-02-958. Washington, DC: GAO.

GAO. 2006. Drug Safety: Improvement Needed in FDA’s Postmarket Decision-Making and Oversight Process. GAO-06-402. Washington, DC: GAO.

Goldhammer A. 2005 (June 8). Statement of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America to Institute of Medicine. Presentation to the Institute of Medicine Committee on the Assessment of the US Drug Safety System. Washington, DC: IOM.

Laffont J, Tirole J. 1991. The politics of government decision-making: a theory of regulatory capture. Quart J Econ 106(4):1089-1127.

Stigler G. 1971. The theory of economic regulation. Bell J Econ Manage Sci 2:2-21.

Thompson L. 2000. User fees for faster drug reviews. Are they helping or hurting the public health? FDA Consum 34(5):25-29.

|

15 |

The Enhancing Drug Safety and Innovation Act of 2006, http://help.senate.gov/S___.pdf. |

Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS). 2006. FDA Scientists Pressured to Exclude, Alter Findings; Scientists Fear Retaliation for Voicing Safety Concerns. [Online]. Available: http://www.ucsusa.org/news/press_release/fda-scientists-pressured.html [accessed July 24, 2006].

Wolfe S. 2006. Public Citizen: The 100th Anniversary of the FDA: The Sleeping Watchdog Whose Master Is Increasingly the Regulated Industries. [Online]. Available: http://www.pharmalive.com/News/index.cfm?articleid=353196&categoryid=54 [accessed July 11, 2006].

Zelenay JL. 2005. The Prescription Drug User Fee Act: is a faster Food and Drug Administration always a better Food and Drug Administration? Food Drug Law J 60(2):261-338.