Summary

Seafood (referring in this report to all commercially obtained fish, shellfish, and mollusks, both marine and freshwater) is a nutrient-rich food source that is widely available to most Americans. It is a good source of high-quality protein, is low in saturated fat, and is rich in many micronutrients. Seafood is often also a rich source of the preformed long-chain polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which are synthesized in limited amounts by the human body from alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), a fatty acid found in several vegetable, nut, and seed oils (e.g., walnut and flaxseed oils). In the past several years, research has implicated seafood, particularly its contribution of EPA and DHA, in various health benefits identified for the developing fetus and infants, and also for adults, including those at risk for cardiovascular disease. Contamination of aquatic food sources, however, whether by naturally-occurring or introduced toxicants, is a concern for US consumers because of adverse health effects that have been associated with exposure to such compounds. Methylmercury can accumulate in the lean tissue of seafood, particularly large, predatory species such as swordfish, certain shark, tilefish, and king mackerel. Lipophilic compounds such as dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) can be found in the fatty tissue of some fish. High levels of particular microbial pathogens may be present during certain seasons in various geographic areas, which can compromise the safety of products commonly eaten raw, such as oysters. Additionally, some population groups have been identified as being at greater risk from exposure to certain contaminants in seafood.

In consideration of these issues, the US Department of Commerce,

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) asked the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies to examine relationships between benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption to help consumers make informed choices. The expert committee was asked to prioritize the potential for adverse health effects from both naturally occurring and introduced toxicants in seafood, assess evidence on availability of specific nutrients in seafood compared to other food sources, determine the impact of modifying food choices to reduce intake of naturally occurring and introduced toxicants on nutrient intake and nutritional status within the US population, develop a decision path for US consumers to weigh their seafood choices to obtain nutritional benefits balanced against exposure risks, and identify data gaps and recommend future research.

The committee concentrated primarily on seafood derived from marine (saltwater) sources and included freshwater fisheries when appropriate to the discussion. Further, the committee recognized that these sources vary greatly in their level of contamination depending on local conditions, and that individual states have issued a large number of advisories based on assessment of local conditions. Although the committee was not asked to consider questions or make recommendations about environmental concerns related to seafood, it recognizes that the impact of changes in seafood production, harvesting, and processing have important environmental consequences.

To address the task of assessing benefit-risk trade-offs, the committee took a three-step approach. The steps that framed this analytical approach were: (1) analysis and balancing of the benefits and risks (including attention to characteristics that distinguish target populations as well as substitution predictions); (2) analysis of consumer perceptions and decision-making (understanding decision contexts and their variability, and assessing consumers’ behavior regarding how they perceive and make choices); and (3) design and evaluation of the decision support program itself (including format and structure of information, media, and combination of communication products and processes). The aim of the analysis in step 1 is to assess the overall effect of seafood selections rather than the assessment of reduction in a specific risk or enhancement of a specific benefit.

ANALYSIS OF THE BALANCING OF BENEFITS AND RISKS OF SEAFOOD CONSUMPTION

The scientific assessment and balancing of the benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption is a complex task. Diverse evidence, of varying levels of completeness and uncertainty, on different types of benefits and risks must be combined to carry out the assessment required as a first step in designing consumer guidance. In light of the uncertainty in the available

scientific information associated with both nutrient intake and contaminant exposure from seafood, no summary metric adequately captures the complexity of seafood benefit/risk trade-offs. Thus, the committee developed a four-part qualitative protocol adapted from previous work (IOM, 2003) to evaluate and balance benefits and risks. Following the protocol, the committee considered consumption patterns of seafood; the scope of the benefits and risks associated with different patterns of consumption for the population as a whole and, if appropriate, for specific target populations; and changes in benefits and risks associated with changes in consumption patterns. It then balanced the benefits and risks to come to specific guidance for healthy consumption for the population as a whole, and, as appropriate, for specific target populations.

Consumption of Seafood in the United States

Seafood consumption has increased over the past century, reaching a level of more than 16 pounds per person per year in 2003. The ten types of seafood consumed in the greatest quantities among the US general population (from highest to lowest) are shrimp, canned tuna, salmon, pollock, catfish, tilapia, crab, cod, clams, and flatfish (e.g., flounder and sole). The nation’s seafood supply is changing, however, and this may have a significant impact on seafood choices in the future. The preference among consumers for marine types of seafood is leading to supply deficits, and seafood produced by aquaculture is replacing captured supplies for several of these types.

While seafood is recognized as a primary source of the omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids EPA and DHA, not all seafood is rich in these fatty acids. Among types of seafood, shrimp and canned light tuna are the two most commonly consumed, and they are not especially high in EPA and DHA. Eggs and chicken, although not particularly rich sources,1 may contribute to the EPA and DHA content of the US diet because of their frequent consumption. Relative to other foods in the meat, poultry, fish, and eggs group, however, seafood is generally lower in saturated fatty acids and higher in EPA, DHA, and selenium, all of which have been associated with health benefits.

Primary Findings

-

Average quantities of seafood consumed by the general US population, and by several specific population groups, are below levels suggested by

-

many authoritative groups, including levels recommended by the American Heart Association for cardiovascular disease prevention; and

-

For many ethnic and geographic subgroups, there are insufficient data to characterize the intake levels of seafood, EPA, DHA, and other dietary constituents, and to assess the variability of those intakes.

Benefits Associated with Nutrients from Seafood

The high nutritional quality of seafood makes it an important component of a healthy diet. While protein is an important macronutrient in the diet, most Americans already consume enough and do not need to increase their intake. Fats and oils are also part of a healthful diet, but the type and amount of fat can be important—for example, with regard to cardiovascular disease. Many Americans consume greater than recommended amounts of saturated fat as well as cholesterol from high-fat protein foods such as beef and pork. Many seafood selections are lower in total and saturated fats and cholesterol than some more frequently selected animal protein foods such as fatty cuts of beef, pork, and poultry, and are equivalent in amount of fat to some leaner cuts of meat. Since it is lower in saturated fats, however, by substituting seafood more often for other animal foods, consumers can decrease their overall intake of both total and saturated fats while retaining the nutritional quality of other protein food choices.

Seafood is also a primary source of EPA and DHA in the American diet. The contribution of these nutrients to improving health and reducing risk for certain chronic diseases in adults has not been completely elucidated. There is evidence, however, to suggest there are benefits to the developing infant, such as increasing length of gestation, improved visual acuity, and improved cognitive development. In addition, there is evidence to support an overall benefit to the general population for reduced risk of heart disease among those who eat seafood compared to those who do not, and there may be benefits from consuming EPA and DHA for adults at risk for coronary heart disease.

Primary Findings

-

Seafood is a nutrient-rich food that makes a positive contribution to a healthful diet. It is a good source of protein, and relative to other protein foods, e.g., meat, poultry, and eggs, is generally lower in saturated fatty acids and higher in the omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA as well as selenium;

-

The evidence to support benefits to pregnancy outcome in females who consume seafood or fish-oil supplements as part of their diet during pregnancy is derived largely from observational studies. Clinical trials and epidemiological studies have also shown an association between increased

-

duration of gestation and intake of seafood or fish-oil supplements. Evidence that the infants and children of mothers who consume seafood or EPA/DHA supplements during pregnancy and/or lactation may have improved developmental outcomes is also supported largely by observational studies;

-

Observational evidence suggests that increased seafood consumption is associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular deaths and cardiovascular events in the general population. Evidence is insufficient to assess if this association is mediated through an increase in EPA and DHA consumption and/or a decrease in saturated fat consumption and/or other correlates of seafood consumption;

-

Evidence is inconsistent for protection against further cardiovascular events in individuals with a history of myocardial infarction from consumption of EPA/DHA-containing seafood or fish-oil supplements. The protection evidenced by population (observational) studies has not been consistently observed in randomized clinical trials; and

-

Evidence for a benefit associated with seafood consumption or fish-oil supplements on blood pressure, stroke, cancer, asthma, type II diabetes, or Alzheimer’s disease is inconclusive. Whereas observational studies have suggested a protective role of EPA/DHA for each of these diseases, supportive evidence from randomized clinical trials is either nonexistent or inconclusive.

Risks Associated with Seafood

The safety of seafood in the US has increased in recent decades, although there are still a number of chemical and microbial hazards that are present in seafood. Whether a contaminant poses a health risk to consumers depends on the amount present in the food and the potential outcome from exposure. Consumers are exposed to a complex mixture of dietary and non-dietary contaminants. However, most studies of the risks associated with seafood focus on one contaminant at a time rather than a mixture. The extent to which such coexposures might affect the toxicity of seafoodborne contaminants is largely unknown. Similarly, few data are available on the extent to which beneficial components of seafood, such as selenium, might mitigate the risks associated with seafoodborne contaminants. The evidence reviewed indicates that the levels of different contaminants in seafood depend on several factors such as species, size, location, age, and feed source. Levels of some contaminants in seafood vary substantially due to their geographic localization; areas of highest variation tend to be mostly freshwater.

Consumption of aquatic foods is the major route of human exposure to methylmercury (MeHg). The seafood choices a consumer makes and the frequency with which different species are consumed are thus important determinants of methylmercury intake. Exposure to MeHg among US

consumers in general is a concern because there is uncertainty about the potential for subtle adverse health outcomes. Since the most sensitive subgroup of the population to MeHg exposure is the developing fetus, intake recommendations are developed for and directed to the pregnant woman rather than to the general population.

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs), including dioxins and PCBs, can be found in the fatty tissue of all animal-derived foods, including seafood. Exposure to these compounds among the general population has been decreasing in recent decades. The greatest concern is for population groups exposed to POPs in seafood obtained through cultural, subsistence, or recreational fishing, because of reliance on fish from locations that may pose a greater risk.

In contrast to heavy metal contaminants and POPs, the number of reported illnesses from seafoodborne microbial contaminants has remained steady over the past several decades. Exposure to vibrio and norovirus infections is still a concern, however, because they continue to be associated with consumption of raw molluscan shellfish. Strategies for minimizing the risk of seafoodborne illnesses are, to some extent, hazard-specific, but overall include avoiding types of seafood identified as being more likely to contain certain contaminants, and following general food safety guidelines, which include proper cooking.

Primary Findings

-

Levels of contaminants in seafood depend on several factors, including species, size, harvest location, age, and composition of feed. MeHg is the seafoodborne contaminant for which the most exposure and toxicity data are available; levels of MeHg in seafood have not changed substantially in recent decades. Exposure to dioxins and PCBs varies by location and vulnerable subgroups (e.g., some American Indian/Alaskan Native groups living near contaminated waters) may be at increased risk. Microbial illness from seafood is acute, persistent, and a potentially serious risk, although incidence of illness has not increased in recent decades.

-

Considerable uncertainties are associated with estimates of the health risks to the general population from exposures to methylmercury and persistent organic pollutants at levels present in commercially obtained seafood. The available evidence to assess risks to the US population is incomplete and useful to only a limited extent.

-

Consumers are exposed to a complex mixture of dietary and non-dietary contaminants whereas most studies of risks associated with seafood focus on a single contaminant.

Balancing Benefits and Risks

From its review of consumption, benefits, and risks, the committee recommends that:

Recommendation 1: Dietary advice to the general population from federal agencies should emphasize that seafood is a component of a healthy diet, particularly as it can displace other protein sources higher in saturated fat. Seafood can favorably substitute for other high biologic value protein sources while often improving the overall nutrient profile of the diet.

Recommendation 2: Although advice from federal agencies should also support inclusion of seafood in the diets of pregnant females or those who may become pregnant, any consumption advice should stay within federal advisories for specific seafood types and state advisories for locally caught fish.

Recommendation 3: Appropriate federal agencies (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA], the US Environmental Protection Agency [USEPA], and the Food and Drug Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services [FDA]) should increase monitoring of methylmercury and persistent organic pollutants in seafood and make the resulting information readily available to the general public. Along with this information, these agencies should develop better recommendations to the public about levels of pollutants that may present a risk to specific population subgroups.

Recommendation 4: Changes in the seafood supply (source and type of seafood) must be accounted for—there is inconsistency in sampling and analysis methodology used for nutrients and contaminant data that are published by state and federal agencies. Analytical data is not consistently revised, with separate data values presented for wild-caught, domestic, and imported products.

Drawing on these recommendations and its benefit-risk assessment protocol, the committee identified four population groups for which the data support subgroup-specific conclusions. In the committee’s judgement, the variables that distinguish between these populations facing different benefit-risk balances based on existing evidence are (1) age, (2) gender, (3) pregnancy or possibility of becoming pregnant, or breastfeeding, and (4) risk of coronary heart disease, although the evidence for a benefit to adult males and females who are at risk for coronary heart disease is not sufficient to warrant inclusion as a separate group within the decision-making framework. The groups and appropriate guidance are listed in Box S-1 below.

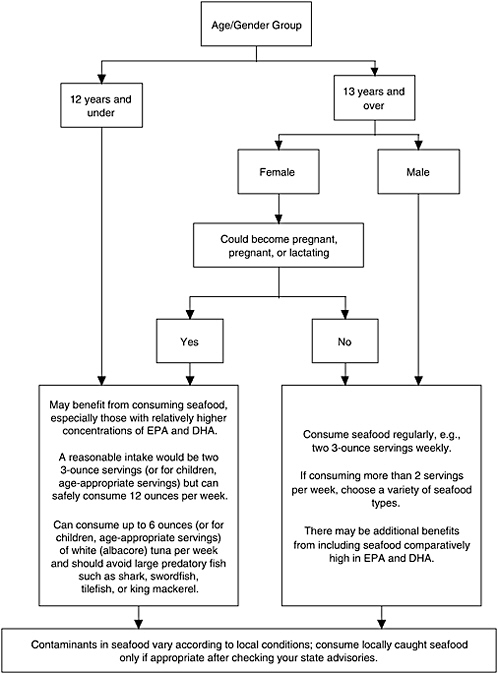

To balance the benefits and risks, the recommendations, as they apply to the target population groups 1–3, are arrayed in a decision pathway (shown in Figure S-1) that illustrates the committee’s resulting analysis of the balance between benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption.

|

BOX S-1 Population Groups and Appropriate Guidance

|

FIGURE S-1 The committee’s decision pathway derived from the balance between benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption. The diagram highlights the variables that group consumers into target populations that face different benefits and risks and should receive tailored advice.

NOTE: The wording in this figure has not been tested among consumers. Designers will need to test the effects of presenting information on seafood choices in alternative formats.

UNDERSTANDING CONSUMER DECISION MAKING AS THE BASIS FOR THE DESIGN OF CONSUMER GUIDANCE

The second step in the approach to balancing benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption is developing an understanding of the context within which consumers make seafood choices. Receiving new information, such as dietary guidance, does not automatically lead consumers to change their food consumption patterns. Food choice is influenced by a complex information environment that includes taste, availability, and price, as well as guidance, point-of-purchase information, labeling, and advice from health care providers. In the context of this environment, specific pieces of guidance may have limited impact, although evidence suggests that this impact varies significantly and in many instances is not well measured or understood. There are several factors that mitigate against current advice having the intended consequences in terms of consumer choice. Increased understanding of the individual, socio-cultural, and environmental factors that influence consumer choice is necessary for the design of consumer guidance, especially where the intent is to communicate balancing of benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption.

Seafood choices, like all consumption choices, entail value trade-offs; some individuals will choose high risks to achieve what they value as high benefits (e.g., consume raw seafood because of its pleasurable taste), while others may prefer to “play it safe.” Individual differences in tastes, preferences, beliefs and attitudes, and situations complicate the task of informing and supporting benefit-risk trade-off decisions. Audience segmentation and targeting, therefore, is essential for effective communication, because decision objectives, risk attitudes, and people’s knowledge about and interest in decision-making vary. Guidance in making seafood choices should allow consumers to access information in a clear and easy-to-understand format. It should also be structured to support decision-making, and allow consumers to access additional layers of information when they want them.

BALANCING CHOICES: SUPPORTING CONSUMER SEAFOOD CONSUMPTION DECISIONS

The third design step for developing specific support for seafood consumption decisions is production and evaluation of the information itself, including ways to integrate the benefit and risk considerations in mock-up examples of how such information might be provided. It is apparent in any discussion of seafood consumption that “one size does not fit all” and that messages about consumption often have to be individualized for different groups, such as subsistence fishers, pregnant women, children, and native populations, to mention a few. The committee’s balancing of the benefits and risks of different patterns of seafood consumption for different subpopula-

tions is illustrated in Figure S-1. Different subpopulations could be used by federal agencies as the basis for targeting advice to consumers on seafood consumption. Resulting communication products should be tested empirically. Through a brief set of questions, a decision pathway can segment and channel consumers into relevant benefit-risk subpopulations in order to provide benefit and risk information that is tailored to each group. The inclusion of alternative presentations of benefit-risk advice and information in the design of consumer advice recognizes that while some consumers prefer to follow the advice given to them by experts, others want to decide on the benefit-risk trade-offs for themselves.

One of the challenges in supporting informed consumer choice is how governmental agencies communicate health benefits and risks to both the general population and to specific subgroups or particularly vulnerable populations. Developing effective tools to disseminate current and emerging information to the public requires formal evaluation, as well as an iterative approach to design. The use of tailored messages and community-level involvement on an ongoing basis is likely to improve the effectiveness of communication between federal agencies and target populations.

Primary Findings

-

Advice to consumers from the federal government and private organizations on seafood choices to promote human health has been fragmented. Benefits have been addressed separately from risks; portion sizes differ from one piece of advice to another. Some benefits and some risks have been addressed separately from others for different physiological systems and age groups. As a result, multiple pieces of guidance—sometimes conflicting—simultaneously exist for seafood.

-

Given the uncertainties present in underlying exposure data and health impact analysis, there is no single summary metric that adequately captures the complexity of balancing benefits and risks associated with seafood for purposes of providing guidance to consumers. An expert judgement technique can be used to consider benefits and risks together, to yield specific suggested consumption guidance.

Recommendations

Recommendation 5: Appropriate federal agencies should develop tools for consumers, such as computer-based, interactive decision support and visual representations of benefits and risks that are easy to use and to interpret. An example of this kind of tool is the health risk appraisal (HRA), which allows individuals to enter their own specific information and returns appropriate recommendations to guide their health actions. The model de-

veloped here provides this kind of evidence-based recommendations regarding seafood consumption. Agencies should also develop alternative tools for populations with limited access to computer-based information.

Recommendation 6: New tools apart from traditional safety assessments should be developed, such as consumer-based benefit-risk analyses. A better way is needed to characterize the risks combined with benefit analysis.

Recommendation 7: A consumer-directed decision path needs to be properly designed, tested, and evaluated. The resulting product must undergo methodological review and update on a continuing basis. Responsible agencies will need to work with specialists in risk communication and evaluation, and tailor advice to specific groups as appropriate.

Recommendation 8: Consolidated advice is needed that brings together different benefit and risk considerations, and is tailored to individual circumstances, to better inform consumer choices. Effort should be made to improve coordination of federal guidance with that provided through partnerships at the state and local level.

Recommendation 9: Consumer messages should be tested to determine if there are spillover effects for segments of the population not targeted by the message. There is suggestive evidence that risk-avoidance advice for sensitive subpopulations may be construed by other groups or the general population as appropriate precautionary action for themselves. While emphasizing trade-offs may reduce the risk of spillover effects, consumer testing of messages should address the potential for spillover effects explicitly.

Recommendation 10: The decision pathway the committee recommends, which illustrates its analysis of the current balance between benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption, should be used as a basis for developing consumer guidance tools for selecting seafood to obtain nutritional benefits balanced against exposure risks. Real-time, interactive decision tools, easily available to the public, could increase informed actions for a significant portion of the population, and help to inform important intermediaries, such as physicians.

Recommendation 11: The sponsor should work together with appropriate federal and state agencies concerned with public health to develop an interagency task force to coordinate data and communications on seafood consumption benefits, risks, and related issues such as fish stocks and seafood sources, and begin development of a communication program to help consumers make informed seafood consumption decisions. Empirical evaluation of consumers’ needs and the effectiveness of communications should be an integral part of the program.

Recommendation 12: Partnerships should be formed between federal agencies and community organizations. This effort should include targeting and involvement of intermediaries, such as physicians, and use of interactive

Internet communications, which have the potential to increase the usefulness and accuracy of seafood consumption communications.

RESEARCH GAPS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Seafood Consumption

Recommendation 1: Research is needed on systematic surveillance studies of targeted subpopulations. Such studies should be carried out using state-of-the-art assessment methods to determine the intake levels of seafood, EPA/DHA and other dietary constituents, and the variability of those intake levels among population groups.

Recommendation 2: Sufficiently large analytic samples of the most common seafood types need to be obtained and examined. These samples should be used to determine the levels of nutrients, toxicants, and contaminants in each species and the variability between them, which should be reported transparently.

Recommendation 3: Additional data is needed to assess benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption within the same population or population subgroup.

Pregnant and Lactating Women

Recommendation 4: Better data are needed to determine if outcomes of increasing consumption of seafood or increasing EPA/DHA intake levels in US women would be comparable to outcomes of populations in other countries. Such studies should be encouraged to include populations of high fish-consumers outside the United States to determine if there are differences in risks for these populations compared to US populations.

Recommendation 5: Dose-response studies of EPA/DHA in pregnant and lactating women are needed. This information will help determine if higher intakes can further increase gestation duration, reduce premature births, and benefit infant development. Other studies should include assessing whether DHA alone can act independently of EPA to increase duration of gestation.

Infants and Toddlers

Recommendation 6: Research is needed to determine if cognitive and developmental outcomes in infants are correlated with performance later in childhood. This should include:

-

Evaluating preschool and school-age children exposed to EPA/ DHA in utero and postnatally, at ages beginning around 4 years when executive function is more developed; and

-

Evaluating development of school-age children exposed to variable EPA/DHA levels in utero and postnatally with measures of distractibility, disruptive behavior, and oppositional defiant behavior, as well as more commonly assessed cognitive outcomes and more sophisticated tests of visual function.

Recommendation 7: Additional data are needed to better define optimum intake levels of EPA/DHA for infants and toddlers.

Children

Recommendation 8: Better-designed studies about EPA/DHA supplementation in children with behavioral disorders are needed.

Adults at Risk for Chronic Disease

Recommendation 9: In the absence of meta-analyses that systematically combine quantitative data from multiple studies, further meta-analyses and larger randomized trials are needed to assess outcomes other than cardiovascular, in particular total mortality, in order to explore possible adverse effects of EPA/DHA supplementation.

Recommendation 10: Additional clinical research is needed to assess a potential effect of seafood consumption and/or EPA/DHA supplementation on stroke, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and depression.

Recommendation 11: Future epidemiological studies should assess intake of specific species of seafood and/or biomarkers, in order to differentiate the health effects of EPA/DHA from the health effects of contaminants such as methylmercury.

Health Risks Associated with Seafood Consumption

Recommendation 12: More complete data are needed on the distribution of contaminant levels among types of fish. This information should be made available in order to reduce uncertainties associated with the estimation of health risks for specific seafoodborne contaminant exposures.

Recommendation 13: More quantitative characterization is needed of the dose-response relationships between chemical contaminants and adverse health effects, in the ranges of exposure represented in the general US population. Such information will reduce uncertainties associated with recommendations for acceptable ranges of intake.

Recommendation 14: In addition, the committee recommends more research on useful biomarkers of contaminant exposures and more precise quantitative characterization of the dose-response relationships between chemical contaminants and adverse health effects, in the ranges of exposure represented in the general US population, in order to reduce uncertainties associated with recommendations for acceptable ranges of intake.

Designing Consumer Guidance

Recommendation 15: Research is needed to develop and evaluate more effective communication tools for use when conveying the health benefits and risks of seafood consumption as well as current and emerging information to the public. These tools should be tested among different communities and subgroups within the population and evaluated with pre- and post-test activities.

Recommendation 16: Among federal agencies there is a need to design and distribute better consumer advice to understand and acknowledge the context in which the information will be used by consumers. Understanding consumer decision-making is a prerequisite. The information provided to consumers should be developed with recognition of the individual, environmental, social, and economic consequences of the advice. In addition, it is important that consistency between agencies be maintained, particularly with regard to communication information using serving sizes.

CONCLUSION

For most of the general population, balancing benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption to obtain nutritional and health benefits can be achieved by selecting seafood from available options in quantities that fall within accepted dietary guidelines. For the specific subgroups identified by the committee, making such selections requires that consumers are aware of both nutrients and contaminants in the seafood available and are provided useful information on both benefits and risks to inform their choices. The committee has put forward its interpretation of the evidence for benefits and risks associated with seafood and considered the balance between them. Recommendations are made to facilitate development of appropriate consumer guidance for making seafood selections, based on the committee’s findings, and research opportunities are identified that will contribute to filling knowledge gaps.