6

Understanding Consumer Decision Making as the Basis for the Design of Consumer Guidance

Chapter 5 outlined the three steps the committee deemed necessary to designing guidance to consumers about balancing benefits and risks in making seafood consumption decisions (see Box 5-1): scientific assessment and analysis of the benefits and risks; analysis of the consumer’s decision making context; and production and evaluation of the guidance. Chapter 5 then detailed Step One: the evidence base for the information to include in the guidance (or what the consumer needs to know to make an informed decision). This chapter presents an approach to Step Two: developing an understanding of how consumers make seafood choices and the informational environment in which they do so. This environment includes both what information the consumer has access to and what the consumer needs or wants to know. Included in this chapter is an overview of the types of information that are currently available and evidence of the degree to which consumer choice has been influenced by it. The chapter then discusses reasons why consumer guidance may have weak or unintended impacts on consumer choice and what must be understood about the consumer decision-making context in order to design effective guidance.

INTRODUCTION

As noted in the previous chapters, there is a wide variety of guidance on seafood consumption currently available to consumers. Based on their analysis of nutritional benefits, some governmental agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have recommended that most Americans consume two 3-ounce (cooked) servings of seafood weekly, with one of these

being a fatty fish (see Chapter 1). Other guidance cautions some consumers against specific types of seafood due to health risks. As shown in preceding chapters, different populations have different benefit-risk profiles, and guidance to consumers should be tailored to reflect this.

Receiving new information, such as dietary guidance, does not automatically lead consumers to change their food consumption patterns. Food choice is influenced by a complex informational environment that also includes labeling, point-of-purchase information, commercial advertising and promotion, and Web-based health information. Specific guidance may have a limited impact, although evidence suggests that this varies significantly and in general is not well measured or understood; current advice may create unintended consequences in consumer choices. A better understanding of the sociocultural, environmental, economic, and other individual factors that influence consumer choice is necessary for the design of effective consumer guidance, especially where the intent is to communicate balancing of benefits and risks associated with its consumption.

FOOD CHOICE BEHAVIOR

Food Consumption Decisions

Identification of Factors Influencing Food Consumption Decisions

Studies of food choice behavior have identified both individual and environmental factors that influence the complex process of decision making (Lutz et al., 1995; Galef, 1996; Drewnowski, 1997; Nestle et al., 1998; Booth et al., 2001; Wetter et al., 2001; Bisogni et al., 2002; Devine, 2005; Raine, 2005; Shepard, 2005). Factors influencing seafood consumption choices are similar to those for other foods (e.g., taste, convenience, or ease of preparation) (Gempesaw et al., 1995).

Individual Influences When consumers are asked what is most important when choosing food, taste is the most likely response (Drewnowski, 1997). However, a variety of other individual factors (e.g., habit) (Honkanen et al., 2005) also influence consumer decisions about consumption or avoidance of specific foods (Lutz et al., 1995; Galef, 1996; Drewnowski, 1997; Nestle et al., 1998; Booth et al., 2001; Bisogni et al., 2002; Devine, 2005). For example, some people will override taste to select foods to benefit their health (Stewart-Knox et al., 2005). The choice for healthfulness is further affected by choice of preparation method and food consumption outside the home (Blisard et al., 2002). For other consumers, issues of convenience, availability, and cost may play greater roles than concerns about health. What is unknown is the degree to which these factors determine final food selection.

Environmental Influences Taste is influenced by genetics (Birch, 1999; Mennella et al., 2005a) and exposure throughout life (Birch, 1998; Birch and Fisher, 1998; Mennella et al., 2005b). Other environmental factors that influence seafood choices include accessibility of seafood as a subsistence food (Burger et al., 1999b), cultural tradition (Willows, 2005), price of seafood and of seafood substitutes (Hanson et al., 1995), and health and nutrition concerns (Gempesaw et al., 1995; Trondsen et al., 2003). For example, some consumers make seafood choices based on concerns about environmental impact (see Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch [http://www.mbayaq.org/cr/seafoodwatch.asp], production methods, or geographical origin (Figure 6-1).

An individual’s food choices are made based on their history but are influenced by a changing environment over time (Devine, 2005; Wethington, 2005). While most patterns of choice (trajectories) are stable throughout life, significant societal and personal events, as well as relationships, influence these patterns. The timing of these events may greatly influence subsequent food choices. In response to these external events and internal changes, individuals may or may not choose to adopt strategies to improve their health and change their lifestyle behaviors. Using the pregnant woman as an example (see Appendix C-1), one can examine the complexity of food choice using the Life Course Perspective framework (see Appendix C-2).

Economic Considerations Associated with Food Choice Behavior

Economic considerations may also influence consumer food choice behavior. Evidence suggests that seafood is a good substitute for other protein foods (Salvanes and DeVoretz, 1997; Huang and Lin, 2000). US consumers have the lowest income elasticity of demand (the percentage change in demand for a 1 percent change in income) for the overall category of “food, beverages, and tobacco” of 114 countries, based on an analysis of 1996 data (Seale et al., 2003). This indicates that, on average, their food expenditures are not very sensitive to income changes. For the subcategory of fish, Seale et al. also found the US expenditure elasticity (the percentage change in demand for a 1 percent change in expenditures on a category) lowest among the 114 countries studied. Similarly, US consumers had the lowest own-price elasticities of demand (the percentage change in demand for a one percent change in price) for fish among the countries studied.

More detailed analysis within the United States suggests further income and price considerations that may influence how consumers implement guidance on seafood choices. For example, Huang and Lin (2000) used 1987–1988 National Food Consumption Survey data to estimate expenditure and own-price elasticities adjusting for changes in the quality of the foods consumed across different income groups. Expenditure and own-

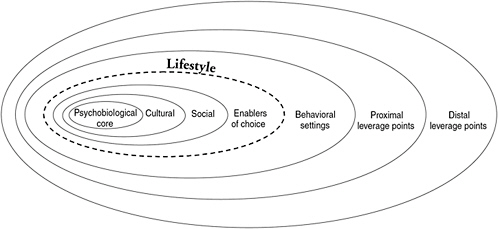

FIGURE 6-1 Framework for factors influencing healthy eating and physical activity behaviors. The schema depicts a psychobiological core composed of genetic, psychological (e.g., self-esteem, body image, disagreement with personal vulnerability or gain from choices), and physiological influences (e.g., gender, age, health status, responses to specific components in food, hunger, and satiety). This core is embedded within a social-cultural context (e.g., families and friends, religion and tradition, economic and other resources, awareness and knowledge of the implications of choice), and impact of consumer advertising and information that can either enhance or inhibit healthful food choices and other lifestyle behaviors. In addition to these individual characteristics, the larger environment (e.g., neighborhoods, communities, schools, worksites) along with policy decisions (e.g., health advisories and guidance; economic and political priorities) greatly influence the individual’s food decisions (Wetter et al., 2001; Raine, 2005). Food availability, convenience, cost considerations, and food subsidies also are included in the environmental layers of influence. SOURCE: Adapted, with permission, from Booth et al. (2001). Copyright 2001 by International Life Sciences Institute.

price elasticities vary between low-, medium-, and high-income consumers, although the extent differs between food products (Yen and Huang, 1996; Huang and Lin, 2000). They also conclude that the quality of items chosen by consumers (e.g., different cuts of beef within the beef subcategory) is clearly linked to income level. Similarly, an analysis of household expenditures on fruits and vegetables shows significant differences in expenditure per capita between low-income and higher-income households, as well as differences in the income elasticity of demand (Blisard et al., 2004). These results suggest that population averages may conceal significant differences between income groups in terms of their demand responses to income, expenditure, and price changes.

Impact of Factors Influencing Food Consumption Decisions

In general, when consumers are presented with new information, e.g., balancing health benefits with risks of seafood choices, food choice behavior theories suggest that they will interpret and respond to this information in light of their existing beliefs, attitudes, and habits, and will be influenced by situational factors as much as or more than by the content of the information.

For example, in a long-term, randomized controlled study involving advice to men with angina to eat more fish and vegetables, small increases in fish consumption were observed (Ness et al., 2004), but this did not appear to improve survival (Ness et al., 2002). Even with carefully planned prospective studies of the consequences of giving advice, it can be difficult to discern the effect of advice, due to potentially confounding influences (see also Impact of State Advisories below). Advice provided publicly may be focused on by the media, reinforced or contradicted by other policy measures, or obscured by other news (Kasperson et al., 2003).

As Ness et al. (2004) illustrated, knowledge does not necessarily lead to the intended changes in consumption patterns. In addition, once a decision is made, many processes are involved in implementing and sustaining a change (Appendix C-3). Among the many theories used to explain both food choice behavior (and its subsequent impact on health) and behavior change (Achterberg and Trenker, 1990), a few are highlighted in Appendix C-2.

The Current Information Environment Influencing Seafood Choices

Consumers have access to several different types of communication that form a complex information environment in which they make decisions. Each of these plays a role in their decisions, either as a source of information or as a facilitator of choice.

A striking aspect of the information available to consumers is that it

is not systematically coordinated. This lack of coordination would not be unexpected between public agencies and private organizations, or between groups who may have different interpretations of the evidence about what is a healthful eating pattern as well as different goals in giving advice. However, even within the federal government, guidance to consumers has not been systematically coordinated, either on a benefit-by-benefit or risk-by-risk basis, as illustrated by the differences between recommendations on portion sizes and frequency of consumption (see Table 1-2 and Appendix Table B-3).

Elements of the information environment which government agencies can control include labels, other point-of-purchase information in the retail environment, and restaurant and fast-food outlet menus.

Labels and Other Point-of-Purchase Information

Ingredient and Nutrition Labeling Ingredient labeling gives consumers content information about packaged seafood products. In some cases, regulation also restricts use of terms in identifying products. For example, only albacore tuna can be labeled as “white tuna,” while “chunk light tuna” may include several species of tuna.

Nutrition labeling in the form of the Nutrition Facts panel is mandatory in the United States for packaged products, while the use of voluntary nutrient content and health claims is also regulated. Fresh foods are exempt from mandatory labeling. In 1992, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued guidelines for a voluntary point-of-purchase nutrition information program for fresh produce and raw fish. The guidelines are scheduled to be revised in 2006 to make them more consistent with mandatory nutrition labeling requirements (Personal communication, K. Carson, Food and Drug Administration, April 1, 2006). To meet the guidelines, a retailer must include the following nutrition information on the point-of-purchase label for seafood that is among the 20 types most commonly eaten in the US: seafood type; serving size; calories per serving; protein, carbohydrate, total fat, cholesterol, and sodium content per serving; and percent of the US Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) for iron, calcium, and vitamins A and C per serving (FDA, 2004a). A serving is defined as 3 ounces or 85 grams cooked weight, without added fat or seasoning.

Qualified Health Claims Labeling While the standard Nutrition Facts format informs consumers about several nutrition characteristics of seafood products, it does not list omega-3 fatty acid content. In 2004, the FDA announced the availability of a qualified health claim for reduced risk of coronary heart disease on conventional foods that contain eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Qualified health claims on

foods must be supported by scientific evidence as outlined in the guidance document, Guidance for Industry and FDA: Interim Procedures for Qualified Health Claims in the Labeling of Conventional Human Food and Human Dietary Supplements (CFSAN, 2003). In addition, the FDA is conducting further consumer studies to make sure the language used in claims is well understood by consumers (FDA, 2004b).

In the interim period, the FDA will prioritize health claims for review based on the potential significance of the product’s health impact on a serious or life-threatening illness, and the strength of evidence in support of the claim. The health claims that will be evaluated first include the benefits of eating foods high in omega-3 fatty acids, including certain fatty fish like ocean salmon, tuna, and mackerel, for reducing the risk of heart disease.

Country of Origin and Other Labeling The 2002 Supplemental Appropriations Act amended the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 to require retailers to inform consumers of the country of origin of wild and farm-raised fish and shellfish. This information can be conveyed by label, stamp, mark, placard, or other clear and visible sign on the product, package, display, holding unit, or bin containing the seafood at the final point of consumption. Food service establishments are exempt, as are processed products.

Box 6-1 describes an unresolved issue over which governmental sector has the authority to control the consumer’s access to certain information

|

BOX 6-1 Challenge to California’s Proposition 65 In 2005, the Food and Drug Administration claimed that California’s action was a violation of federal law. On March 8, 2006, the House passed HR 4167, the National Uniformity for Food Act, which amends the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to “provide for uniform food safety warning notification requirements” and to supersede state legislation and practices on food-warning labels, including Proposition 65. At the writing of this report, the Act had not passed the Senate. An amendment to the Act included a clause to exclude mercury warnings: “Nothing in this Act or the amendments made by this Act shall have any effect upon a State law, regulation, proposition or other action that establishes a notification requirement regarding the presence or potential effects of mercury in fish and shellfish.” SOURCE: http://www.govtrack.us/data/us/bills.text/109/h/h4167.pdf. |

regarding food. In 2004, the Attorney General of California joined a lawsuit filed by the Public Media Center, a nonprofit media and consumer advocacy agency in San Francisco, against the nation’s three largest canned tuna companies to enforce Proposition 65, California’s 1986 law requiring warnings about exposure to contaminants, such as methylmercury.

Restaurant and Fast-Food Menu Information The away-from-home sector is exempt from nutritional and country of origin labeling requirements. Further, many restaurants do not identify seafood products such as breaded fish sandwiches by species. Some of this information is provided voluntarily, and this may increase with consumer demand for specific types of seafood.

In April 2003, the Attorney General of California filed suit against major restaurant chains in the state for violating Proposition 65 requirements to inform consumers of potential exposure to “substances known by the state to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity” by failing to post “clear and reasonable” consumer warnings about exposure to mercury in seafood (i.e., shark, swordfish, and tuna). The suit was settled in early 2005, when most of the restaurants agreed to put up warnings about the risks from mercury in seafood near the front door, hostess desk or reception area, or entry or waiting area (California Office of the Attorney General, [http://ag.ca.gov/newsalerts/2005/05-011.htm]). The information provided in this sector remains largely unregulated. The outcome of the lawsuit concluded that labeling under Proposition 65 was preempted for mercury in tuna, although the decision was specific to the circumstances in the case. All applications of Proposition 65 to food were not preempted by the decision. Moreover, this decision was by a state judge and specific to Proposition 65 and California—not other laws or other states.

Regulated Point-of-Purchase Information Retailers may place nutrition information on individual food wrappers or on stickers affixed to the outside of the food. Compliance with point-of-purchase guidelines is checked by biennial surveys of 2,000 food stores that sell raw produce or fish and the results are reported to Congress. Additionally, every 2 years the FDA publishes, in the Federal Register, revised nutrition labeling data for the 20 most frequently consumed raw fruits, vegetables, and fish.

Recent research suggests that the amount of information available on fresh seafood products in retail settings varies markedly, with counter staff frequently unable to provide additional information (Burger et al., 2004). In addition to the quantity and types of information available to consumers, the accuracy of information should also be considered. Limited tests indicate that seafood products may be misrepresented—for example, sold as wild when they are in fact farmed (Is Our Fish Fit to Eat, 1992; Burros, 2005).

Advertising and Promotion

Advertising and promotion may include nonregulated point-of-purchase information, which can be displayed on placards, shelf tags, or in pamphlets or brochures. In addition to regulated labeling and point-of-purchase information, several types of retail information are available to consumers making food choices. For processed foods, packaging information includes the brand, product name, and unregulated product claims and other information. It is estimated that $7.3 billion was spent on advertising food in 1999 (Story and French, 2004).

As well, several other forms of point-of-purchase (e.g., signage, brochures) and other forms of information (e.g., websites) may be provided. Other means to convey this information to consumers may include live demonstrations, computer booths, or recorded presentations as adjuncts to the printed information.

Web-Based Health Information

Interactive Health Communication Much of the rapidly rising use of the Internet is devoted to seeking health information: four out of five Internet users (95 million Americans) have Internet access to look for health-related information; 59 percent of female users have used the Internet to look for information on nutrition (Fox, 2005). The promise of eHealth and, in particular, interactive health communication (IHC) (Eng et al., 1999; Eng and Gustafson, 1999; Wyatt and Sullivan, 2005), has captured the attention of health communicators, in part due to the ability to target and tailor communications, disseminate them rapidly, and engage the audience in an exchange of information, rather than a one-way message delivery (Gustafson et al., 1999); compared with Griffiths et al., 2006. Evaluation of IHC, which falls under the category of eHealth, remains challenging (Eysenbach and Kummervold, 2005). While ethical issues such as unequal access to the Internet and maintaining confidentiality of information pose challenges, IHC has become an important tool for health communicators.

Online Seafood Information and Advocacy There are currently several examples of online seafood consumption information and advocacy available, as illustrated in Table 6-1. For example, Oceans Alive, a nongovernmental organization (Environmental Defense Network), offers “Buying Guide: Becoming a Smarter Seafood Shopper,” on its website (http://www.oceansalive.org/eat.cfm). Other sites offer nutrition information about seafood; however, a cursory glance suggests that some sites may not be updated frequently, and so may provide out-of-date nutritional and other guidance. Updating is likely to be a challenge for any interactive guidance

TABLE 6-1 A Sampling of Online Consumer Information and Advocacy Sites Which Include Mercury Calculators

|

Website |

Organization |

Type of Organization/Project |

Input |

|

Environmental Working Group (EWG) |

Public health and environmental action organization |

Consumer’s weight (lbs) Consumer’s gender |

|

|

A project of the Center for Consumer Freedom A nonprofit organization supported by restaurants, food companies, and individuals, created by Berman & Co., a public affairs firm which has represented various animal production industries |

Consumer’s weight (lbs) Fish of choice (dropdown menu provided) |

||

|

Got Mercury? |

A project of Turtle Island Restoration Network Public education and campaign to reduce exposure to methylmercury from seafood |

Consumer’s weight (lbs) Type of fish consumer has eaten in a week Amount (oz) of up to three different fish consumer has eaten in a week (dropdown menu provided) |

|

Output |

Notes/Quoted Extracts |

|

Amount of canned albacore and canned light tuna you can safely eat (g/kg of weight/day) Based on FDA’s health standard (i.e., safe dose) |

Assumes that you do not eat any other seafood. Assumes that every can of tuna has an average amount of mercury. The FDA recommends up to 12 ounces a week of a variety of fish. If you eat other seafood, the amount of tuna that you can eat safely will be less than calculated here. EWG recommends that women of childbearing age and children under 5 not eat albacore tuna at all, because a significant portion of albacore tuna has very high mercury levels. People eating this tuna will exceed safe exposure levels by a wide margin. |

|

Amount (oz) of each fish you can eat weekly without introducing new health risks from mercury Based on the US EPA’s Reference Dose Links the US EPA’s “Reference Dose” and the theoretical harm threshold (a number ten times greater, called the “Benchmark Dose lower limit”) to the Glossary section of this website |

The EPA knows the level of exposure that represents a hypothetical risk, but it adjusts it by a factor of 10 in order to arrive at its “Reference Dose.” It’s this smaller, hyper-cautionary number that environmental groups use to scare Americans into thinking that tiny amounts of mercury in fish represent a real health hazard. According to fishy math from EWG and SeaWeb, for instance, your health is in grave danger if you consume just 12 ounces of tuna (canned chunk light) in a given week. This trickery is responsible for a great deal of needless fear. And food-scare groups ignore the fact that health risks from mercury take an entire lifetime to accumulate. It’s simply not possible to get mercury poisoning from eating a week’s worth of any commercially available fish. |

|

Mercury exposure (% of EPA limit) Based on the US EPA’s reference dose |

Please be aware that these values are averages. The concentration of mercury in seafood can be significantly higher or lower than what is represented here. As a precautionary approach, we recommend that women (especially of childbearing age) avoid seafood species that contain higher average levels of mercury. Mercury information for many shellfish species is currently unavailable. Data source: FDA website (http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~frf/sea-mehg.html). Two exceptions are the troll-caught albacore data which come from an Oregon State University study and canned albacore data, which come from an FDA dataset that is not yet published on its site. |

|

Website |

Organization |

Type of Organization/Project |

Input |

|

Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) |

An environmental action organization |

Consumer’s weight (lbs) Types of fish consumer has eaten in the last month Number of portions consumer has eaten of each fish Portion sizes for each fish meal |

|

|

http://www.oceanconservancy.org/site/PageServer?pagename=mercuryCalculator |

The Ocean Conservancy |

A research, education, advocacy organization advocating for the oceans |

Consumer’s weight (lbs) Average number of 6 oz servings/week of different seafood types (list provided) |

tool. Information on the nutrient content of foods, including seafood, can be obtained through the USDA nutrient database (USDA, 2005b; Source: http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/Data/SR18/sr18.html) (see also Chapter 5, Table 5-2 and discussion).

Currently, much of the interactive seafood consumption information available on the Web consists of mercury intake calculators that may include tailoring by the decision-maker’s weight, sometimes gender, and the type and amount of seafood consumed (Table 6-1). In addition, the computerized nutritional information approach has been successful and shown some promise in other domains (Lancaster and Stead, 2002; Eng et al., 1999). Computerized nutrition information in the form of menu planning has been ongoing since the mid-1960s (Balintfy, 1964; Eckstein, 1967) and is still being developed (Bouwman et al., 2005).

Northern Contaminants Program

The Northern Contaminants Program (NCP) is funded by a commitment of one million dollars a year from the Canadian government and managed by aboriginal communities. The aim of the program is to reduce

|

Output |

Notes/Quoted Extracts |

|

Estimated level of blood mercury (µg/L), level of blood mercury that the US EPA considers safe Based on the US EPA’s Reference Dose Link to FDA’s 2003 data on levels of mercury in 17 types of fish |

Because the numbers used in the mercury calculator are averages, the fish you eat may contain mercury at levels significantly higher or lower than the numbers used in this calculator. The results of the calculator are only an estimate of the possible level of mercury in your blood and should not be considered definitive. The estimate does not predict any risk to you or your family. If you are concerned about the calculator’s results or wish to get a more accurate reading through a blood mercury test, you should talk to your doctor. |

|

Total mg/kg mercury per week Based on the US EPA’s Reference Dose |

If your results are less than 0.7 below, your mercury levels are likely within EPA’s recommended range. If your results exceed 0.7, your levels may be higher than EPA recommends. Data source: “Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish & Shellfish,” by FDA and EPA (http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~frf/sea-mehg.html) |

and eliminate some of the contaminants reaching the Arctic, and to inform and educate Northerners about the issue of contaminants. Relevant to this report is the work that is being done to inform and educate Northerner Dwellers about the issue and how to manage their diet around existing and emerging contaminant issues.

The initial response of Northern aboriginal communities to information on contaminants in aquatic food was a dramatic switch away from eating “country foods.” In a region where there are few readily available and affordable nutritional alternatives and 56 percent of the population is “food insecure,” this exposed the population to a greater risk from poor nutrition than that posed by the contaminants. Communication about contaminants also affected the social structure of the region as it had a negative impact on the practice of sharing food, due to concerns that hunters might be poisoning friends and family. There was also a negative impact on the efforts of health workers to encourage breastfeeding in the region.

Under the NCP, any contaminant information has to be filtered through a community committee made up of representatives from the aboriginal and Inuit organizations, and health and wildlife workers. This committee is responsible for taking the messages that scientists may develop, and turning

them into something that can be presented to and discussed with the communities. This communication process has enabled the scientific assessments to be merged into different communication practices that result in better public perception and understanding.

In the Inuit culture, each community has its own particular system of knowledge and way of understanding, and the NCP has adapted communication activities to these systems. Among the targeted and tailored communications activities are school curriculums for children, posters, little newsletters, and fact sheets. Radio, video shows, and a whole myriad of different technologies are used to communicate these messages.

Most of these communications relate to benefits—country foods are good for you and important for good nutrition. Little is said about contaminants because the community had established that people really do not care about bioaccumulation or PCBs. They want to know if their food is good to eat. The community has told the scientists that contaminant messages cannot just be “dumped” on communities. Information has to be put into a context of an overall health and nutrition message. The NCP is delivering these tailored health and nutrition messages, targeted to specific audiences such as youth and pregnant or nursing women through a community-based stakeholder program (Personal communication, E. Loring, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, August 3, 2006; http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/ncp/).

Summary

In summary, guidance to consumers regarding the benefits and risks of seafood consumption may inform individual choices about which types of seafood and how much to consume. The design of guidance should consider the context of other product information, particularly labeling, available to consumers to facilitate choice. These other information sources affect choice as well as influence how effectively consumers can implement their decisions once they are made. This distinction is important. For example, labels provide information that consumers use to decide which products to buy just as consumer guidance does. But they also facilitate choices that have already been made. If, following guidance, consumers decide to add a particular type of seafood from a specific region to their diets, will they be able to effectively identify this product in a retail store? Do restaurant and fast-food outlet menus give sufficient information for consumers to implement their choices made on the basis of guidance?

IMPACT OF INFORMATION ON CONSUMER DECISION MAKING

Although it is difficult to attribute observed behavior changes to specific advice, like national and local fish advisories, awareness of advisories

suggests that they contribute to avoidance. For example, shifts away from traditional (country) foods, much of which is seafood, due to concerns that include mercury and other pollutants, have resulted in striking increases in anemia, dental caries, obesity, heart disease, and diabetes among the native populations of Northern Canada (Willows, 2005). Another example of an unanticipated effect of risk information is the Alar controversy of 1989 (Marshall, 1991), which effectively stigmatized apple consumption until Alar was pulled from the market later that year.

As these examples show, reactions to risk information can prevail over, and change, preferences and markets; consumer information may appear to have little direct influence, but it can have substantial unanticipated consequences. The combination of responses to and changing understanding of food consumption choice consequences can amplify the effects of risk information, which can be further amplified by the media, government, and other parties (Kasperson et al., 2003). Providing information about risks in the absence of benefit information is likely to produce negative responses (Finucane et al., 2003; Slovic et al., 2004), compounding the tendency to omit consideration of factors that are not mentioned explicitly (Fischhoff et al., 1978).

Seafood choices, like all consumption choices, may entail value trade-offs (see Chapter 7). Well-designed guidance and information can simplify making such trade-offs for consumers by:

-

Taking into account consumers’ own decision objectives;

-

Understanding consumers’ decision contexts and prior beliefs;

-

Providing adequate, comprehensible measures for the full range of consequences;

-

Recognizing that value trade-offs are dependent on individual preferences and tastes; and

-

Supporting consistency checks, to help people make decisions consistent with their preferences (Keeney, 2002).

Interpretation of new messages—including labels, warnings, and risk communications—depends on prior knowledge and beliefs (Sattler et al., 1997; Argo and Main, 2004), ethnic and cultural background (Burger et al., 1999a,b; Bostrom and Löfstedt, 2003; Knuth et al., 2003), and other characteristics of individual message recipients, as well as attributes of the messages. In addition to specific content (Bostrom et al., 1994) and attributes such as format, structure, graphics, and wording choices (Schriver, 1989; Atman et al., 1994; Wogalter et al., 1996; Sattler et al., 1997; Schriver, 1997), how messages are processed depends also on the reader’s attributes and motivation, and the salience and importance of the topic to the reader (Wogalter et al., 1996; Zuckerman and Chaiken, 1998).

Knowing how consumers make such decisions is also critical to assessing the likelihood of success of different communication strategies. Hence the design of consumer information about benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption requires assessing the decision goals and decision processes of consumers through formative analyses involving interviews or focus groups, and observational studies, as well as quantitative survey analyses and experimental testing of presentation formats and dissemination outlets. The following discussion summarizes the evidence to date regarding the effects of seafood advisories, labels, point-of-purchase information, and other consumer communications.

Evaluating the Effects of Previous Seafood Consumption Guidance

Evaluating the impact of previous guidance on seafood purchasing behavior can be done either qualitatively or quantitatively. Focus groups have been the traditional qualitative method; responses to surveys provide the quantitative information (Source: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/adme-hg3g.html). Simulations, predictions, and scenarios also can be employed.

Impact of Federal Fish Advisories

In a report to the Interagency Working Group on Mercury Communications, Levy and Derby (2000) described the results of eight focus groups conducted prior to the 2001 US EPA fish advisory. They characterize prior concerns about mercury in fish as low, with the perception that mercury in fish is primarily a pollution problem. Reactions to statements about hazards of mercury in fish and fish consumption advice were interpreted as demonstrating two kinds of spillover effects. The first was a failure to narrow the perception of the at-risk group to be pregnant women who eat a lot of fish; focus group participants concluded that the general public must be at risk for consuming mercury from fish. The second was a general tendency to categorize fish as safe or not without paying much attention to quantitative consumption advice. Also noted was the fact that participants wanted information on fish that were safe to eat as well as on those that were not safe to eat.

Oken et al. (2003) and Shimshack et al. (2005) conducted post hoc analyses of the effects of the 2001 US EPA fish advisory on seafood consumption. Oken et al. (2003) found that issuance of the advisory was correlated with decreased consumption of “dark meat” fish, canned tuna, and “white meat” fish in a study of pregnant women. However, it is unclear whether the decrease is attributable to the advisory because the study lacks controls for other known possible influences on consumption. Shimshack et al. (2005) find evidence suggestive of a decrease in canned fish consumption

after the advisory among those who regularly read newspapers or magazines. Overall, they conclude that the advisory had an effect in that over the period studied the mean expenditure share for canned fish fell for some targeted consumers compared to nontargeted consumers. Again, the study does not control for other factors that may have an important influence on changes in consumption. In addition, neither study controls for actual awareness of the advisory, which makes any attribution of the observed changes difficult. The business press refers to a drop in demand after the joint 2004 US EPA/FDA fish advisory (e.g., Warner, 2005). The committee cannot evaluate these claims due to the lack of any statistical information and controls for other factors that affect sales beyond the effects of the advisories. To the best of the committee’s knowledge there have been, to date, no studies done by government, industry, academia, consumer, or environmental groups that offer a credible measure of market impacts of the 2004 US EPA/FDA fish advisory.

Cohen et al. (2005) carried out simulations of consumer behavior under what they call optimistic, moderate, and pessimistic scenarios for responses to the 2001 advisory. Their optimistic scenario assumes that only women of childbearing age respond to the advisory, and do so by substituting low-mercury seafood for higher mercury seafood. Their moderate scenario assumes that women of childbearing age reduce their seafood consumption by 17 percent in response to the 2001 advisory, with no change in types of seafood consumed. Their pessimistic scenario assumes that all adults decrease seafood consumption by 17 percent. In both the moderate and pessimistic scenarios, an overall decrease in benefits results (estimated changes in Quality Adjusted Life Years from a benefit-risk analysis). The optimistic scenario estimates an increase in net benefits if there is compliance with the 2001 advisory, with no spillover effects. The greatest benefit is derived from eating one fish meal a week, as opposed to none. In summary, the analysis by Cohen et al. suggests that the advisory was appropriate, in theory; but the study is not an empirical evaluation of the effects of the advisories. Further, the study assumed some coronary and stroke risk-reduction benefits that recent reviews suggest may not be empirically substantiated.

The US EPA and FDA carried out two sets of focus group studies prior to issuing their joint 2004 US EPA/FDA fish advisory, for a total of 16 focus groups in seven locations (SOURCE: http://www.epa.gov/waterscience/fishadvice/factsheet.html). In a public presentation, an FDA spokesperson summarized findings from the first eight focus groups in four main points: (1) most participants preferred a simple message conveying that consuming high amounts of methylmercury may harm a child’s development, and what to do to avoid high amounts; (2) some participants wanted more information about how methylmercury would affect health, and more data on particular species of fish; (3) some participants think of fish consump-

tion as a whole, and do not distinguish between commercially and sport- or recreationally caught fish; (4) almost all participants reported that they and their children would avoid species designated “do not eat,” regardless of whether or not they were in the targeted audience (Davidson, 2004).

Detailed reports from these focus group studies are not available, although information shows that the focus groups included pregnant or lactating women and racially diverse groups of both sexes, and were conducted in coastal as well as noncoastal locations (Davidson, 2004).

Impact of State Fish Advisories

Survey evaluations suggest that awareness of state fish advisories is low overall. Between one-half and two-thirds of sports fishers reported awareness of state or local advisories in studies of advisory effectiveness (Burger and Waishwell, 2001; Anderson et al., 2004). Tilden et al. (1997), Anderson et al. (2004), and Knobeloch et al. (2005) found that awareness was higher among males than females, with less than half of the women who consume recreationally caught fish aware of advisories.

Risk information of the type found in fish advisories appears to increase reluctance to consume seafood proportionately to benefits when the risks are low, and without regard to benefits when the risks are high (Knuth et al., 2003). Further, there is preliminary evidence suggesting that risk-risk information (comparing the risks of seafood with risks of other foods) may influence risk perceptions more than benefit-risk information (for risks and benefits of seafood) (Knuth et al., 2003).

As is shown in Table 1-2 and Appendix Table B-3, seafood advisories and guidance have been issued by federal, state, and local authorities with conflicting objectives and differing assumptions, even to the point of inconsistent serving sizes. Even an expert reader would find it challenging to integrate these different pieces of advice with one another.

In general, it requires careful experimental design to be able to attribute the effects of specific communications (Golding et al.,1992; Johnson et al., 1992). Experimental evidence shows that warnings can change perceptions and beliefs (Wolgater and Laughrey, 1996; Sattler et al., 1997; Burger and Waishwell, 2001; Riley et al., 2001; Argo and Main, 2004; Knobeloch et al., 2005), but unintended effects, such as overreactions, may occur (Wheatley and Wheatley, 1981; Levy and Derby, 2000; Shimshack et al., 2005).

Labeling Effectiveness and Effects of Health Claims

While there is little evidence pertaining to seafood labels per se, there is considerable evidence on labeling effectiveness in general. In their systematic review of 129 studies, Cowburn and Stockley (2003) concluded that most

consumers claim to look at nutrition labels at least sometimes, but actual use is not widespread. Evidence on consumer understanding of nutrition labels is mixed; while nutrition labels appear to enable simple comparisons, consumers have difficulty using them for more complex tasks, like placing food into consumers’ overall dietary context. The review summarizes findings on label formatting as well, and recommends using boxes for the information; standard, familiar, consistent formatting; and thin alignment lines. Other formatting information reviewed suggested that pie charts are difficult for consumers to understand and should not be used, and that consumers using bar charts tended to compare the length of the bars without taking note of the scales (Cowburn and Stockley, 2003). Recent formative research on more graphic presentation of nutritional information suggests that “traffic light” formats (Food Standards Agency, 2005) may be effective. These rely on the familiarity of the traffic light metaphor, and the ease with which people interpret their colors.

Research on Qualified Health Claims as Applied to Functional Foods In their survey of consumers in Finland, Denmark, and the United States (n=1533, stratified by country), Bech-Larsen and Grunert (2003) found that perceived healthiness of functional foods was primarily determined by the perceived healthiness of the base foods (orange juice, yogurt and non-butter spread) used in their experiment regardless of the additional functional component. Health claims on the label increased the perceived healthiness of functional foods (Bech-Larsen and Grunert, 2003; Williams, 2005).

The optimal presentation of health claims may be a short health claim on the package front, with a longer panel on the back (Wansink et al., 2004). While health claims can change attitudes toward foods, qualifying such claims appropriately based on the quality of the underlying science is a challenging communications task. In tests of several formats, including adjectives embedded in statements and various report card formats (Derby and Levy, 2005), strength-of-science disclaimers did not have the intended effects.

Table 6-2 summarizes the current seafood consumption information environment. Information from the table can be used to identify opportunities for improving this environment with existing information. As illustrated in the table, the most salient gap is insufficient evaluation of the current consumer seafood information environment (e.g., marketing research) and a lack of emphasis on benefits of seafood consumption. Most information available focuses on risks alone. Other shortfalls include the limited reach of state advisories, lack of or potentially misleading (out of date, or inappropriate use of Reference Dose [RfD]) use of quantitative benefit and risk information in interactive online consumer guidance, and limited provision

TABLE 6-2 Summary of Current Seafood Consumption Information Environment

|

|

Benefit/Risk Message |

Source |

Medium/Channel |

Intended Audience(s) |

Available Evaluation Evidence |

|

Federal Advisories |

Mercury risks |

FDA, US EPA |

Mass media, broadcast |

Females of childbearing age, infants, and children |

Insufficient evaluation of market impact Suggestion of spillover effects, including possible stigmatization of seafood (Levy and Derby, 2000; Davidson, 2004) |

|

State Advisories |

Risks: 30 percent on mercury |

State health and environmental agencies |

Brochures, government websites, signs |

Various |

Evaluations suggest limited effectiveness One-fifth to one-half of sports fishers are aware of state or local advisories in studies of advisory effectiveness (Burger and Waishwell, 2001; Anderson et al., 2004) |

|

Regulated Point-of- Purchase Information |

Nutritional information, country of origin, risk |

Safeway, Albertson’s, Wal-Mart, Whole Foods, etc. |

Point-of-purchase placards, shelf tags, pamphlets/brochures; individual food wrappers and stickers on the outside of food |

All consumers |

Suggestion that these displays can increase market share of product by 1–2 percent over 2 years (Cowburn and Stockley, 2003) No specific evaluations of point-of-purchase displays of mercury in seafood; evaluations of point-of-purchase displays for seafood source suggest false claims are made regarding origin (Burger et al., 2004) |

|

Labeling |

Types of seafood and how much to consume; nutritional information and risks |

Retailers |

Point-of-purchase placards, shelf tags, pamphlets/brochures; individual food wrappers and stickers on the outside of food |

All consumers |

Most consumers claim to look at nutrition labels at least sometimes, but actual use is less widespread (Cowburn and Stockley, 2003) No specific evaluation of seafood labels—limited labeling requirements |

|

Qualified Health Claims |

Eating foods high in omega-3 fatty acids to decrease risk of heart disease |

Producers |

On products/menus |

All consumers |

These claims increase the perceived healthfulness of functional foods (Bech-Larsen and Grunert, 2003; Williams, 2005) |

|

Web-based Health Information |

Nutrition information (although often not updated), risk, mercury, Dioxin-like Compiounds, ecological |

Environmental Non-govenmental Organizations |

Internet, interactive |

Internet users, environmentally concerned |

Committee unaware of any evaluations. Advice is given in a limited number of categories; limited quantitative information; very limited info on benefits of seafood consumption |

|

Mercury Intake Calculators |

Risk focus: mercury |

Various organizations (public health, environmental action, nonprofit, education/campaign, research advocacy) |

Internet, interactive |

Internet users, concerned consumers (inferred) |

Misuse of RfD, committee unaware of any evaluations |

|

Northern Contaminants Program |

Benefits, balancing choices |

Health Canada |

Mixed media, participative program |

Northern communities |

Program limited to Northern Canada (Kuhnlein et al., 2000; Mos et al., 2004; Willows, 2005), evaluations suggest program effectively prevents substituting low nutrition foods for seafood; questions about costs |

of point-of-purchase information. Notably, federal and state government agencies are not currently providing interactive online guidance.

SETTING THE STAGE FOR DESIGNING CONSUMER GUIDANCE

Seafood is a complex commodity, with a very wide range of individual products with varying price levels, and nutrient and contaminant profiles. The availability and affordability of seafood products is changing (see Chapter 2); this is likely to influence the ability of consumers to implement the seafood choices that they want to make to balance benefits and risks. The market context in which consumers make choices should be kept in mind when designing guidance. For example, information accompanying the guidance could point to lower-cost alternatives for increasing intake of seafood rich in EPA and DHA.

Seafood choices, like all consumption choices, entail value trade-offs; for example, seafood higher in EPA and DHA may cost more than seafood that is lower. Other seafood may be more economical but contain higher levels of contaminants. Some individuals will accept high risks to achieve what they value as high benefits (e.g., consume raw seafood because of its pleasurable taste), while others may prefer to “play it safe.”

Individual differences in tastes, preferences, beliefs and attitudes, and situations complicate the task of informing and supporting benefit-risk trade-off decisions. Food choices may be predicated on different objectives—a healthy baby for the pregnant woman, or weight loss for someone who is overweight. Audience segmentation and targeting is essential for effective communication (see above), not only because decision objectives and risk attitudes vary, but because people’s knowledge and interest varies.

Tailored communications are more effective than general advice (de Vries and Brug, 1999; Rimer and Glassman, 1999). For example, access to appropriate, science-based information on both the benefits and risks of seafood consumption is particularly critical for pregnant women to enable them to adhere to health guidance messages (Athearn et al., 2004). Therefore, constructing information on balancing the benefits and risks of seafood consumption during pregnancy must address pregnant women separately from other consumers.

A recent multi-state focus group study (Athearn et al., 2004) revealed that most but not all women were aware of and followed the recommendation to avoid undercooked or raw seafood during pregnancy. In contrast, the recommendation not to serve smoked fish cold without heating was less familiar, which was reflected in higher reported consumption levels (25.8 percent for smoked fish vs. 14.5 percent for undercooked or raw seafood consumption). This appeared to be related to lack of exposure to this recommendation (especially from participants’ doctors) and lack of publicized

evidence of risk (in terms of outbreaks, case studies, or risk assessment measures). It was also related to the lack of clarity as to whether “smoked” fish included lox and hot-smoked and/or cold-smoked fish. The authors concluded that it is critical for pregnant women to understand why the information is being targeted to them, and to make certain to entitle food safety information as “applicable to pregnant women” specifically.

Consumer messages about diet and nutrition need to be understandable, achievable, and consistent across information sources. They must also “address sources of discomfort about dietary choices; they must engender a sense of empowerment; and they should motivate both by providing clear information that propels toward taking action and appeals to the need to make personal choices” (Borra et al., 2001). Consumers need access to information that is in a clear and easy-to-understand format, that is structured to support decision-making, and that allows consumers access to additional layers of information when they want them (Morgan et al., 2001).

It is important for those designing consumer guidance to conduct an empirical analysis of the decision-making process. Part of this assessment is understanding consumers’ decision context when they are presented with guidance suggesting changes in food choice behavior. One way to gain such understanding is to construct an empirically based scenario reflective of the consumers’ world, rather than that of the scientist, as described in the Family Seafood Selection Scenario shown in Appendix C-4. This should be based on the best available evidence from consumer research.

Pre-implemention and post hoc evaluation of the impact of consumer guidance must control for differences, as well as changes in factors including incomes and prices, that occur during the period studied in order to isolate the effect of the guidance itself. Otherwise, the effect of the guidance on changes in consumption may be over- or underestimated. These types of controls have been lacking in previous evaluations, making the effect of the guidance unclear.

FINDINGS

-

Consumers are faced with a multitude of enablers and barriers when making and implementing food choices. Dietary advice is just one component in making food choices.

-

Advice to consumers from the federal government and private organizations on seafood choices to promote human health has been fragmented. Benefits have been addressed separately from risks; portion sizes differ from one piece of advice to another. Some benefits and some risks have been addressed separately from others for different physiological systems and age groups. As a result, multiple pieces of guidance—sometimes conflicting—exist simultaneously for seafood.

-

The existence of multiple pieces of advice, without a balancing of benefits and risks, may lead to consumer misunderstanding. As a result, individuals may under- or overconsume foods relative to their own health situations.

-

There is inconsistency between current consumer advice in relation to portion sizes. For example, the FDA/US EPA fish advisory uses a 6-ounce serving size whereas nutritional advice from some government agencies uses a 3-ounce serving size.

-

Evidence is insufficient to document changes in general seafood consumption in response to the 2001 or 2004 methylmercury advisories.

-

It is apparent that messages about consumption often have to be individualized for different groups such as pregnant females, children, the general population, subsistence fishermen, and native populations.

-

Involving representatives of targeted subpopulations (e.g., Arctic Circle campaign) in both the design and evaluation of communications intended to reach those subpopulations can improve the effectiveness of those communications.

-

There are models for designing guidance, e.g., using full programs, that some individual communities (e.g., Arctic Circle campaign) have contributed to understanding the effects of different modes of health communication and modifying messages to achieve the desired community and/or individual response.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 1: Appropriate federal agencies should develop tools for consumers, such as computer-based, interactive decision support and visual representations of benefits and risks that are easy to use and to interpret. An example of this kind of tool is the health risk appraisal (HRA), which allows individuals to enter their own specific information and returns appropriate recommendations to guide their health actions. The model developed here provides this kind of evidence-based recommendation regarding seafood consumption. Agencies should also develop alternative tools for populations with limited access to computer-based information.

Recommendation 2: New tools apart from traditional safety assessments should be developed, such as consumer-based benefit-risk analyses. A better way is needed to characterize the risks combined with benefit analysis.

Recommendation 3: A consumer-directed decision path needs to be properly designed, tested, and evaluated. The resulting product must undergo methodological review and update on a continuing basis. Responsible agencies will need to work with specialists in risk communication and evaluation, and tailor advice to specific groups as appropriate.

Recommendation 4: Consolidated advice is needed that brings together different benefit and risk considerations, and is tailored to individual circumstances, to better inform consumer choices. Effort should be made to improve coordination of federal guidance with that provided through partnerships at the state and local level.

Recommendation 5: Consumer messages should be tested to determine if there are spillover effects for segments of the population not targeted by the message. There is suggestive evidence that risk-avoidance advice for sensitive subpopulations may be construed by other groups or the general population as appropriate precautionary action for themselves. While emphasizing trade-offs may reduce the risk of spillover effects, consumer testing of messages should address the potential for spillover effects explicitly.

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 1: Research is needed to develop and evaluate more effective communication tools for use when conveying the health benefits and risks of seafood consumption as well as current and emerging information to the public. These tools should be tested among different communities and subgroups within the population and evaluated with pre- and post-test activities.

Recommendation 2: Among federal agencies there is a need to design and distribute better consumer advice to understand and acknowledge the context in which the information will be used by consumers. Understanding consumer decision making is a prerequisite. The information provided to consumers should be developed with recognition of the individual, environmental, social, and economic consequences of the advice. In addition, it is important that consistency between agencies be maintained, particularly with regard to communication information using serving sizes.

SUMMARY

Mass communication has inarguably changed the world, using a one-size-fits-all model. There are health messages that everyone of a certain generation has heard (“Just Say No”). But like shoes, advice is more helpful if it is sized appropriately and designed appropriately for the intended use. As communications technologies have advanced, the communicator’s ability to tailor communications to reach large audiences rapidly, and interact with them, has also advanced.

REFERENCES

Achterberg C, Trenkner LL. 1990. Developing a working philosophy of nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education 22(4):189–193.

Anderson HA, Hanrahan LP, Smith A, Draheim L, Kanarek M, Olsen J. 2004. The role of sport-fish consumption advisories in mercury risk communication: A 1998–1999 12-state survey of women age 18–45. Environmental Research 95(3):315–24.

Argo JJ, Main KJ. 2004. Meta-analyses of the effectiveness of warning labels. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 23(2):193–208.

Athearn PN, Kendall PA, Hillers VV, Schroeder M, Bergmann V, Chen G, Medeiros LC. 2004. Awareness and acceptance of current food safety recommendations during pregnancy. Maternal and Child Health Journal 8(3):149–162.

Atman CJ, Bostrom A, Fischhoff B, Morgan MG. 1994. Designing risk communication: Completing and correcting mental models of hazardous processes, Part I. Risk Analysis 14(5):779–788.

Balintfy JL. 1964. Menu planning by computer. Communications of the ACM 7(4):255–259.

Bech-Larsen T, Grunert KG. 2003. The perceived wholesomeness of functional foods: A conjoint study of Danish, Finnish, and American consumers’ perception of functional foods. Appetite 40:9–14.

Birch LL. 1998. Development of food acceptance patterns in the first years of life. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 57(4):617–624.

Birch LL. 1999. Development of food preferences. Annual Review of Nutrition 19(1): 41–62.

Birch LL, Fisher JO. 1998. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics 101(3 Part 2):539–549.

Bisogni CA, Connors M, Devine CM, Sobal J. 2002. Who we are and how we eat: A qualitative study of identities in food choice. Journal of Nutrition and Education Behavior 34(3):128–139.

Blisard N, Lin B-H, Cromartie J, Ballenger N. 2002. America’s changing appetite: Food consumption and spending to 2020. FoodReview 25(1):2–9.

Blisard, Noel, Hayden Stewart, and Dean Jolliffe. 2004 (May). Low-Income Households’ Expenditures on Fruits and Vegetables. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Agricultural Economic Report Number 833.

Booth SL, Sallis JF, Ritenbaugh C, Hill JO, Birch LL, Frank LD, Glanz K, Himmelgreen DA, Mudd M, Popkin BM, Rickard KA, St Jeor S, Hays NP. 2001. Environmental and societal factors affect food choice and physical activity: Rationale, influences, and leverage points. Nutrition Reviews 59(3 Part 2):S21–S39.

Borra S, Kelly L, Tuttle M, Neville K. 2001. Developing actionable dietary guidance messages: Dietary fat as a case study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 101(6):678–684.

Bostrom A, Lofstedt RE. 2003. Communicating risk: Wireless and hardwired. Risk Analysis 23(2):241–248.

Bostrom A, Atman CJ, Fischhoff B, Morgan MG. 1994. Evaluating risk communication: completing and correcting mental models of hazardous processes, Part II. Risk Analysis 14(5):789–798.

Bouwman LI, Hiddink GJ, Koelen MA, Korthals M, van’t Veer P, van Woerkum C. 2005. Personalized nutrition communication through ICT application: How to overcome the gap between potential effectiveness and reality. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 59(Suppl 1):S108–S115.

Burger J, Waishwell L. 2001. Are we reaching the target audience? Evaluation of a fish fact sheet. Science of the Total Environment 277(1–3):77–86.

Burger J, Pflugh KK, Lurig L, Von Hagen LA, Von Hagen S. 1999a. Fishing in urban New Jersey: Ethnicity affects information sources, perception, and compliance. Risk Analysis 19(2):217–229.

Burger J, Stephens WL Jr, Boring CS, Kuklinski M, Gibbons JW, Gochfeld M. 1999b. Factors in exposure assessment: Ethnic and socioeconomic differences in fishing and consumption of fish caught along the Savannah River. Risk Analysis 19(3):427–438.

Burger J, Stern AH, Dixon C, Jeitner C, Shukla S, Burke S, Gochfeld M. 2004. Fish availability in supermarket and fish markets in New Jersey. Science of the Total Environment 333(1):89–97.

Burros M. 2005 (April 10). Stores say wild salmon but tests say farm bred. New York Times. [Online]. Available: http://www.rawfoodinfo.com/articles/art_wildsalmonfraud.html [accessed October 17, 2005].

CFSAN (Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition). 2003. Guidance for Industry and FDA: Interim Procedures for Qualified Health Claims in the Labeling of Conventional Human Food and Human Dietary Supplements. Rockville, MD: Food and Drug Administration. [Online]. Available: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/hclmgui3.html [accessed October 17, 2005].

CFSAN. 2005. Methylmercury in Fish—Summary of Key Findings from Focus Groups about the Methylmercury Advisory. [Online]. Available: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/admehg3g.html [accessed August 28, 2006].

CFSAN. 2006a. Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish. [Online]. Available: http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~frf/sea-mehg.html [accessed August 28, 2006].

CFSAN (Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition). 2006. Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish. [Online]. Available: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~frf/sea-mehg.html [accessed August 28, 2006].

Cohen et al. 2005. A quantitative risk-benefit analysis of changes in population fish consumption. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 29(4):325–334.

Cowburn G, Stockley L. 2003. A Systematic Review of the Research on Consumer Understanding of Nutrition Labelling. Brussels, Belgium: European Heart Network.

Davidson M. 2004 (January 25–28). Presentation for the National Forum on Contaminants in Fish. San Diego, CA. [Online]. Available: http://www.epa.gov/waterscience/fish/forum/2004/presentations/monday/davidson.pdf [accessed May 11, 2006].

de Vries H, Brug J. 1999. Computer-tailored interventions motivating people to adopt health promoting behaviours: Introduction to a new approach. Patient Education Counseling 36(2):99–105.

Derby BM, Levy AS. 2005. Working Paper: Effects of Strength of Science Disclaimers on the Communication Impacts of Health Claims. [Online]. Available: http://www.fda.gov/OHRMS/dockets/dockets/03N0496/03N-0496-rpt0001.pdf [accessed August 29,2006].

Devine CM. 2005. A life course perspective: Understanding food choices in time, social location, and history. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 37(3):121–128.

Drewnowski A. 1997. Taste preferences and food intake. Annual Review of Nutrition 17:237–253.

Eckstein EF. 1967. Menu planning by computer: The random approach. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 51(6):529–533.

Eng TR, Gustafson DH, Henderson J, Jimison H, Patrick K. 1999. Introduction to evaluation of interactive health communication applications. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 16(1):10–15.

EWG (Environmental Working Group). 2006. EWG Tuna Calculator. [Online]. Available: http://www.ewg.org/issues/mercury/20031209/calculator.php [accessed August 28, 2006].

Eysenbach G, Kummervold PE. 2005. Is cybermedicine killing you? The story of a cochrane disaster. Journal of Medical Internet Research 7(2):e21. [Online]. Available: http://www.jmir.org/2005/2/e21/ [accessed September 7, 2006].

FDA. 2004a. Food Labeling, Title 21. Federal Register 2:20–52. [Online]. Available: http://a257.g.akamaitech.net/7/257/2422/12feb20041500/edocket.access.gpo.gov/cfr_2004/aprqtr/21cfr101.9.htm [accessed March 22, 2006].

FDA. 2004b. FDA Implements Enhanced Regulatory Process to Encourage Science-Based Labeling and Competition for Healthier Dietary Choices. [Online]. Available: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/nuttfbg.html [accessed March 22, 2006].

Finucane ML, Peters E, Slovic P. 2003. Chapter 10: Judgment and decision making: The dance of affect and reason. In: Schneider SL, Shanteau J, eds. Emerging Perspectives on Judgment and Decision Research. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 327–364.

Fischhoff B, Slovic P, Lichtenstein S. (1978). Fault trees: Sensitivity of assessed failure probabilities to problem representation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 4:330–344.

FishScam.com. Mercury Calculator. [Online]. Available: http://www.fishscam.com/mercury-Calculator.cfm [accessed August 28, 2006].

Focus Groups about the Methylmercury Advisory. [Online]. Available: http://0-www.cfsan.fda.gov.lilac.une.edu/~dms/admehg3g.html [accessed May 11, 2006].

Fox S. 2005. Health Information Online. Pew Internet and American Life Project, Washington DC, May 17, 2005. [Online]. Available: http://www.pewInternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Healthtopics_May05.pdf [accessed April 10, 2006].

FSA (Food Standards Agency). 2005. Signpost Labelling: Creative Development of Concepts Research Report. UK: Food Standards Agency. [Online]. Available: http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/signpostingnavigatorreport.pdf [accessed April 13, 2006].

Galef BG Jr. 1996. Food selection: Problems in understanding how we choose foods to eat. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 20(1):67–73.

Gempesaw CM, Bacon JR, Wessels CR, Manalo A. 1995. Consumer perceptions of aquaculture products. American Journal of Agriculture Economics 77:1306–1312.

Golding D, Krimsky S, Plough A. 1992. Evaluationg risk communication: Narrative versus technical presentations of information about radon. Risk Analysis 12(1):27–35.

Got Mercury? Eating Lots of Seafood? Use This Advanced Mercury Calculator to See Your Exposure. [Online]. Available: http://gotmercury.org/english/advanced.htm [accessed August 28, 2006].

Griffiths F, Lindenmeyer A, Powell J, Lowe P, Thorogood M. 2006. Why are health care interventions delivered other the Internet? A systematic review of the public literature. Journal of Medical Internet Research 8(2):e10. [Online]. Available: http://www.jmir.org/2006/2/e10/ [accessed September 7, 2006].

Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Boberg E, Pingree S, Serlin RE, Granziano F, Chan CL. 1999. Impact of a patient-centered, computer-based health information/support system. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 16(1):1–9.

Hanson GD, Herrmann RO, Dunn JW. 1995. Determinants of seafood purchase behavior: Consumers, restaurants, and grocery stores. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 77(5):1301–1305.

Honkanen P, Olsen SO, Verplanken B. 2005. Intention to consume seafood—the importance of habit. Appetite 45(2):161–168.

Huang KS, Lin B-H. 2000. Estimation of Food Demand and Nutrient Elasticities from Household Survey Data. Economic Research Service Technical Bulletin No. 1887. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture.

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Northern Contaminants Program. [Online]. Available: http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/ncp/ [accessed September 7, 2006].

Is Our Fish Fit to Eat. 1992. Consumer Reports 57(2):103.

Johnson BB, Sandman PM, Miller P. 1992. Testing the Role of Technical Information in Public Risk Preception. [Online]. Available: http://www.piercelaw.edu/risk/vol3/fall/johnson.htm [accessed August 27, 2006].

Kasperson JX, Kasperson RE, Pidgeon N, Slovic P. 2003. Chapter 1: The social amplification of risk: Assessing fifteen years of research and theory. In: Pidgeon N, Kasperson RE, Slovic P, eds. The Social Amplification of Risk. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 13–46.

Keeney RL. 2002. Common mistakes in making value trade-offs. Operations Research 50(6):935–945.

Knobeloch L, Anderson HA, Imm P, Peters D, Smith A. 2005. Fish consumption, advisory awareness, and hair mercury levels among women of childbearing age. Environmental Research 97(2):220–227.

Knuth BA, A Connelly N, Sheeshka J, Patterson J. 2003. Weighing health benefit and health risk information when consuming sport-caught fish. Risk Analysis 23(6):1185–1197.

Kuhnlein HV, Receveur O, Chan HM, Loring E. 2000. Centre for Indigenous People’s Nutrition and Environment (CINE). Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue, QC: CINE.

Lancaster T, Stead L. 2005. Self-help interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3):CD001118.

Levy AS, Derby B. 2000. Report Submitted to Interagency Working Group on Mercury Communications. Findings from focus group testing of mercury-in-fish messages. [Online]. Available: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~acrobat/hgfoc10.pdf [accessed May 11, 2006].

Lutz SM, Smallwood DM, Blaylock JR. 1995. Limited financial resources constrain food choices. FoodReview 18(1):13–17.

Marshall E. 1991. A is for apple, Alar, and—alarmist. Science 254(5028):20–22.

Mennella JA, Pepino MY, Reed DR. 2005a. Genetic and environmental determinants of bitter perception and sweet preferences. Pediatrics 115(2):e216–e222.

Mennella JA, Turnbull B, Ziegler PJ, Martinez H. 2005b. Infant feeding practices and early flavor experiences in Mexican infants: An intra-cultural study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 105(6):908–915.

Monterey Bay Aquarium. 1999–2006. Seafood Watch: Make Choices for Healthy Oceans. [Online]. Available: http://www.mbayaq.org/cr/seafoodwatch.asp [accessed August 28, 2006].

Morgan MG, Fischhoff B, Bostrom A, Atman CJ. 2001. Risk Communication: A Mental Models Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mos L, Jack J, Cullon D, Montour L, Alleyne C, Ross PS. 2004. The importance of imarine foods to a near-urban first nation community in coastal British Columbia, Canada: Toward a benefit-risk assessment. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 67(8–10):791–808.

Ness AR, Hughes J, Elwood PC, Whitley E, Smith GD, Burr ML. 2002. The long-term effect of dietary advice in men with coronary disease: Follow-up of the Diet and Reinfarction trial (DART). European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 56(6):512–518.

Ness AR, Ashfield-Watt PA, Whiting JM, Smith GD, Hughes J, Burr ML. 2004. The long-term effect of dietary advice on the diet of men with angina: The diet and angina randomized trial. Journal of Human Nutrition and Diet 17(2):117–119.

Nestle M, Wing R, Birch L, DiSogra L, Drewnowski A, Middleton S, Sigman-Grant M, Sobal J, Winston M, Economos C. 1998. Behavioral and social influences on food choice. Nutrition Review 56(5 Pt 2):S50-S64; discussion S64–S74.

NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council). 2006. Mercury Contamination in Fish. A Guide to Staying Healthy and Fighting Back. [Online]. Available: http://www.nrdc.org/health/effects/mercury/index.asp [accessed December 8, 2006].

The Ocean Conservancy. 2001–2006. Mercury Calculator. [Online]. Available: http://www.oceanconservancy.org/site/PageServer?pagename=mercuryCalculator [accessed August 28, 2006].

Oceans Alive. 2005. Buying Guide: Becoming a Smarter Seafood Shopper. [Online]. Available: www.oceansalive.org/eat.cfm?subnav=buy [accessed October 17, 2005].

Office of the Attorney General. 2001. Attorney General Lockyer Announces Court Approval of Settlement Requiring Major Restaurant Chains to Post Warnings About Mercury in Fish. [Online]. Available: http://ag.ca.gov/newsalerts/2005/05-011.htm [accessed May 11, 2006].

Oken E, Kleinman KP, Berland WE, Simon SR, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. 2003. Decline in fish consumption among pregnant women after a national mercury advisory. Obstetrics and Gynecology 102(2):346–351.

109th Congress, 2D Session. 2006. H.R. 4167: An Act. [Online]. Available: http://www.gov-track.us/data/us/bills.text/109/h/h4167.pdf [accessed August 28, 2006].

Park H, Thurman WN, Easley JE Jr. 2004. Modeling inverse demands for fish: Empirical welfare measurement in Gulf and South Atlantic Fisheries. Marine Resource Economics 19:333–351.

Raine K. 2005. Determinants of healthy eating in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 96(Supplement 3):S8–S14.

Riley DM, Fischhoff B, Small M, Fischbeck P. 2001. Evaluating the effectiveness of risk-reduction strategies for consumer chemical products. Risk Analysis 21(2):357–369.

Rimer, BK, Glassman B. 1999. Is there a use for tailored print communications in cancer risk communication? Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Monographs 25:140–148.

Salvanes KG, DeVoretz DJ. 1997. Household demand for fish and meat products: Separability and demographic effects. Marine Resource Economics 12(1):37–55.

Sattler B, Lippy B, Jordan TG. 1997. Hazard Communication: A Review of the Science Underpinning the Art of Communication for Health and Safety. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor.

Schriver K. 1989. Evaluating text quality: The continuum from text-focused to reader-focused methods. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 32(4):238–255.

Schriver KA. 1997. Dynamics in Document Design: Creating Text for Readers. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Science Panel on Interactive Communication and Health. 1999. Wired for Health and Well-Being: The Emergence of Interactive Health Communication. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. [Online]. Available: http://www.health.gov/scipich/pubs/finalreport.htm [accessed September 6, 2006].

Seale J Jr, Regmi A, Bernstein J. 2003 (October). International Evidence on Food Consumption Patterns. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Technical Bulletin Number 1904.

Shepard R. 2005. Influences on food choice and dietary behavior. Elmadfa I editor. Diet Diversifications and Health Promotion. Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger AG. Pp. 36–43.

Shimshack JP, Ward MB, Beatty TKM. 2005. Working paper: Are mercury advisories effective? Information, education, and fish consumption.

Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, MacGregor DG. 2004. Risk as analysis and risk as feeling: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis 24(2):311–322.

Stewart-Knox B, Hamilton J, Parr H, Bunting B. 2005. Dietary strategies and uptake of reduced fat foods. Journal of Human Nutrition and Diet 18(2):121–128.

Story M, French S. 2004. Food advertising and marketing directed at children and adolescents in the US. International Journal of Behavior, Nutrition, and Physical Activity. Published online February 10 at http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=416565.