12

LONG BEAN

In Asia there is a special vegetable, renown by growers for its productivity, by chefs for its appearance, and by diners for its flavor and tender-crisp texture. Reportedly, it is one of Southeast Asia’s top ten vegetables, grown especially in southern China and Taiwan. That report, however, does it less than justice. In addition, it is the most widely grown legume of the Philippines, where it is known as “poor-man’s meat.” It also is very well known in Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Bangladesh, India, and more.

In recent decades, this popular bean has begun picking up aficionados far beyond Asia. Indeed, there is now a rising regard for it worldwide. Many countries already consider it a leading Oriental vegetable. In Europe, for instance, it is being grown extensively. And the United States has also begun producing it on a large scale for Chinese, Thai, Filipino, Vietnamese, and Indian restaurants. It is now found year-round in America’s Asian markets and in those supermarkets that have specialty produce sections. Yet the demand keeps rising. California growers, for example, can’t seem to produce enough; importers bring in additional supplies from Mexico and the Caribbean to meet the needs of places such as Los Angeles and San Francisco.

This special foodstuff is the pod of an unusual legume. It resembles a snap bean except for one singular fact: it is pencil-thin and as much as a meter long. Often called yardlong bean in English, these green to pale-green pods are tender, stringless, succulent, and sweet. Typically, they are sliced and boiled and served with a little butter, like string beans. Their crisp texture and flavor hold up well when steamed or stir-fried. Most enthusiasts claim they resemble French beans. Some detect a mushroom-like taste. A few note in them a hint of asparagus, a connection reflected in this plant’s other common name, “asparagus bean.” All agree, however, that it is delicious.

A surprising thing about this “Oriental” vegetable is that it is not from the East at all. In the beginning—thousands of years ago—it was unknown to any Asian, or for that matter any European or New World inhabitant. But it was well known to Africans. This historical fact is a fairly new realization. A century ago even botanists were fooled into labeling the plant Vigna sinensis (bean of China). But now we know that it is nothing more than a

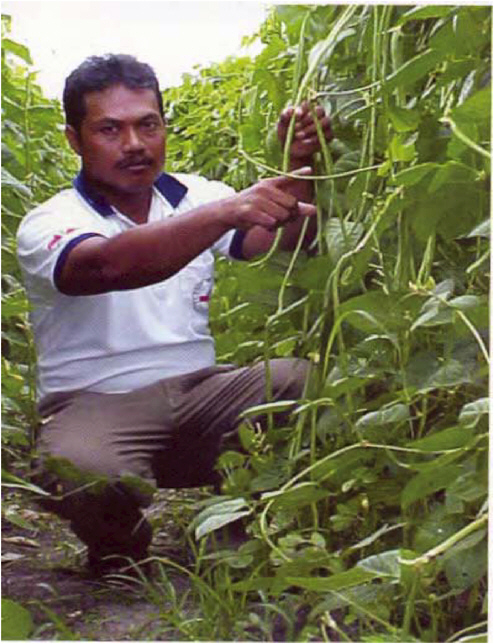

This delightful vegetable resembles a snap bean except for the singular fact that it is pencil-thin and up to a meter long. Often called yardlong bean in English, its green to pale-green pods are tender, stringless, succulent, and sweet. A surprising thing about this universally acclaimed “Oriental vegetable” is that it is a very special form of cowpea—a plant of unquestioned African origin (see Chapter 5). Now is the time to welcome long bean back home and put it to work in Africa. (East West Seeds International)

very special form of cowpea, Vigna unguiculata—a plant that unquestionably arose out of tropical Africa thousands of years ago (see Chapter 5).

This ancient African, which has blossomed to become a modern Queen of Asian Cuisine, is an oddly shaped vegetable, so long as to seem grossly out of proportion. No wonder some people call it snake bean. The strange thing is that this snap-cowpea’s main evolution happened after it left home, so the long, long, long pod is hardly known in the lands that gave the species birth.

Now is the time to welcome back this child of Africa, and to put it to work as in the rest of the world. Indeed, in principle at least, this wanderer from the local genepool should be in virtually every African village. It lends itself to poor people’s needs and conditions. It is productive, yielding a lot of food in a very small space. On worn-out soils it is said to outyield peanuts. A true legume, it is largely independent of fertilizer….enriching soil by trapping atmospheric nitrogen in nodules on its roots. It is not only tasty; it fits into African cuisine, especially the vegetable-laden sauces and relishes.

Long beans thrive in hot humid climates, and produce food very quickly.

Indeed, the succulent leaves can be harvested as soon as 21 days after planting, and some types produce harvestable pods within 60 days. The main varieties continue producing over long periods of time, thus giving rise to an extended harvest that keeps providing fresh pods for months.

That harvest is salable, profitable and, above all, nutritious. Not for nothing do Filipinos call it poor-man’s meat. Both seeds and tender leaves contain 25 percent protein, of high nutritional quality. The US National Aeronautics and Space Administration is so impressed with this plant’s nutritional potential it is considering growing it in space to feed astronauts.

PROSPECTS

There are bright prospects for long bean in the African diet.

Within Africa

Already in certain parts of Africa cowpea pods are eaten. For this reason, the extra-long, highly developed versions now livening cuisines and brightening dinner plates from New Delhi to New Orleans won’t arrive as a foreign food. They are meatier, sweeter, and a paler shade of green than are Africa’s current type. Thus, these foreign counterparts should take on quickly when people find how tasty and tender and attractive they are.

Humid Areas Excellent.

Dry Areas Good. Cowpeas are especially important in regions that are a little too hot and a little too dry for beans and peanuts. Although for top production and pod quality they need water, this is not so difficult to provide in an intensively produced backyard crop. Long bean, however, may be less drought tolerant than cowpea even though it is the same species.

Upland Areas Good. Long beans are said to produce poorly at elevation in the tropics. Nonetheless, there are many pockets where temperatures will prove conducive to this fast-maturing annual.

Beyond Africa

Although the long bean is far better known outside its African homelands, it still has untapped potential in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Yet that potential is likely to be exploited without too much help from public science.

USES

This is another multipurpose plant.

Pods The pods are picked when they are still smooth and immature, before the seeds swell. They are eaten fresh, frozen, or canned. At this young and tender stage, they can be prepared in various ways. Most are sliced and sautéed or stir-fried. Recent suggestions by a cookery consultant include the following: stewed with tomato sauce; boiled and drained, then seasoned with lemon juice and oil; or simmered in butter or oil and garlic. Overcooking is to be avoided: it turns them mushy.

Shoots In many parts of the tropics the young stem tips are steamed or boiled and eaten like asparagus.

Leaves In many areas the leaves of long bean (as well as of cowpea) are also regularly consumed. To make a good spinach the leaves must be young and tender.1 Although they are usually simply boiled and eaten, some are crushed, fried, and boiled. Also, some cowpea leaves are dried and ground into a powder that is stored for use during the time of year when fresh vegetables are scarce. In some areas, the mature leaves are boiled about 15 minutes, drained, dried in the sun, and stored for use as a relish. The rapid boiling (blanching) improves the storage and quality.

Experiments in Uganda and Tanzania have shown that removing all the tender leaves three times at weekly intervals, starting five or seven weeks after sowing, has no adverse effect on cowpea seed yields (although it may delay flowering). Thus, even the growers of the grain type can benefit from these cowpea greens.

Other Uses Long beans can also be used as fodder. In India and some other countries, cowpea is grown as a dual purpose crop: the green pods are harvested for use as a vegetable and the residual plant material, containing about 12 percent protein on a dry matter basis, is used for feeding livestock.

NUTRITION

Long bean pods provide only about 50 calories per 100 g when cooked, and are low in protein (>3 percent2). They also provide modest vitamin C (about 15 mg) and provitamin A (23 g RAE), but have good levels of folate (about 45 g), so critical for growing new cells during pregnancy and infancy. As noted, the tender leaves of the plant are nutritious as well. These contain 25 percent protein as a percentage of dry weight, and the protein is of high quality.

This productive legume yields a lot of food in a very small space. On worn-out soils it is said to out-produce peanuts. A true legume, it is largely independent of fertilizer— enriching soil by trapping atmospheric nitrogen in nodules on its roots. It not only fits into African farming it fits into African cuisine, especially into the vegetable-laden sauces and relishes. These tasty, universally admired treats therefore hold out the prospect of a good income for those who choose to grow them for profit. (East West Seeds International)

HORTICULTURE

Long bean is a vigorous annual that is propagated by seed. Its long, trailing growth requires a trellis or pole for best production. The plant will climb by itself, but still needs some help and a very strong trellis system. Poles are also satisfactory, especially if slanted. Training the vine is said to be no more difficult than training a tomato or pea plant.

Typically, the seeds are planted in rows beside a trellis or in hills beside a pole. In the latter case, it has been recommended that 5-6 seeds be planted together for each pole, and then thinned to leave 3 seedlings. The plant begins producing marketable pods 60 days after sowing. At that stage the pods, hanging in pairs, range from 35 to 60 cm in length. Each pod forms rapidly, growing to marketable length in just 9 days after the flower opens.

The plant thrives in average garden soil that is loose and friable. Soil that is too rich in nitrogen fosters leaf growth over pod production. Since these are legumes, some growers inoculate the seed with nitrogen-fixing bacteria as an alternative to using nitrogen fertilizer. Long bean uses the cowpea (EL strain) rhizobium, which means that it will grow well wherever cowpea does. Thus, in most of Africa no inoculation should be needed. Elsewhere, and especially on barren soils, commercial cowpea inoculum is readily available.

The fact that this versatile crop is a form of cowpea (blackeye pea to Americans) is clear if the plant is let go to seed. In parts of China, long bean is allowed to mature a crop of seeds at the end of the season.

HARVESTING AND HANDLING

The pods keep coming throughout summer and into the fall, and have to be harvested frequently (weekly, if not daily). If they are left unharvested the plants stop producing. They are usually picked when about half the diameter of a pencil, before the seeds have filled out inside, and when they still snap when bent. If that stage is missed, the seeds swell and the pod itself turns tough and inedible.

Yields depend on the site and the grower, but in a field test at Riverside, California researchers measured marketable yields of up to 11,100 kg per hectare with three different cultivars of bush long beans.3

The pods are best when eaten soon after harvesting but they can also be blanched and frozen for storage. If refrigerated, they keep in a plastic bag for up to 5 days. US Department of Agriculture recommendations for commercial dealers are to store them at 4°-7°C and 90-95 percent relative humidity, which provides a storage life of 7 to 10 days.

Marketing long beans is usually not too difficult. However, they must be picked exactly on time and handled with care. As one review noted: “It is easy to make them look bad…old, dry beans look terrible.” The reviewer recommended choosing “slender, crisp, blemish-free beans” and warned that harvested pods quickly develop “rusty patches.”

LIMITATIONS

As with common beans, it is recommended to rotate the planting locations every year and not plant at the same spot within 3-4 years.

In different locations different pests are likely to be encountered. Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne sp.) cause severe problems on cowpea in many areas of the world, including the US. Nematode resistance varieties are the best and most economical solution to this problem. In California the following warning has been given: “Aphids, particularly the cowpea aphid (Aphis craccivora), are drawn to the pods, leaves and stems. Planting the crop near others infested with this aphid, is ‘asking for trouble.’ Thrips tend to be a pest early in the season if temperatures are cool, but the plants will often outgrow them, especially as the weather gets warmer and the plants grow faster. Mites can be a problem, primarily after insecticide applications, which often lead to mite outbreaks.” Lygus bug (Lygus Hesperus) attacks the young floral buds and developing pods of blackeye cowpeas so if potentially a severe problem on long bean as well. In the southeastern United States, cowpea curculio and pod sucking bugs (including the green stink bug Nezara viridula) are major pests of cowpea and will attack long bean as well.

It seems logical to assume that long beans are susceptible to all cowpea diseases. Indeed, the same report from Califonia noted that, “they are damaged by fungi causing rust and mildew as well as by cowpea aphid-borne mosaic virus and cowpea witches’ broom virus. Virus control is aided by destroying infected plant materials and controlling aphids, whiteflies, leafhoppers and beetles that carry the virus from plant to plant. [Long beans] often are relatively pest-free compared to green bean varieties; however, the bean shoot fly and the bean pod fly may hamper growth and pod production. Remove and burn damaged plant materials to prevent spread of pest species.”

NEXT STEPS

Because of global experience with long bean, African nations could mount programs right now to foster its adoption and better use. Anyone involved in vegetable production in Africa could get involved. A continent-wide program to advance and nurture long bean could take advantage of the varying experiences among countries. The best seeds and knowledge exist in Asia, so there could also be an intercontinental swap of germplasm and

expertise. Many varieties unknown in Africa are available, generally identified by the color of mature seed. Examples include the purple-hulled, pink-eyed, dark-brown seeded, white-seeded, and speckle-seeded. There are also purple-podded and knuckle-podded varieties. Asian countries could do much by transferring seeds and horticultural know-how, and could possibly receive much in return from the biodiversity of long bean’s ancestral home.

As noted, cowpea pods have been traditionally eaten in some areas of Africa. Even now, these, together with the plant’s fresh green leaves, are exceptionally important because they are among the earliest foods available at the end of the “hungry time.” Together with long bean, these are equally deserving of support and improved use.

Africans are not used to eating green cowpea pods as a green vegetable, but rather they prefer dry cowpea grain. They need to know that long bean is better consumed as green tender pod, for seed of long bean is lighter than cowpea, and so are not as productive when seed is used compared to green pods.

Food Technology This “new,” elongated cowpea pod should be checked in various African dishes. This would likely turn up many a potential market success. Frozen vegetable processors should try long bean in mixed packages of frozen vegetables.

Horticultural Development The newer bush varieties in Asia also deserve consideration. They have the same meter-long pods but require no trellis or pole and thus are easier to manage. In the Philippines, Bush Sitao (a cross between long bean and common cowpea) reportedly is replacing the viney form in the favor of farmers. It is bush-shaped, needs no trellis, and is less susceptible to wind damage than long bean.

The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture in Nigeria has developed several lines of vegetable cowpea that resemble long bean in some respect (tender pods). The lines were actually developed from the Philippine “bush sitao." Most are determinate plant type.

There is a concern of heavy pesticide use in long bean in Southeast Asian countries. This is an area where research is needed to find ways to produce this crop using reduced or minimum pesticides.

SPECIES INFORMATION

Botanical Name Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis (L.) Verdc.

Synonyms Vigna sinensis subsp. sesquipedalis (L.) Van Eselt.; Vigna sesquipedalis (L.) Fruwirth

Family Leguminosae. Subfamily: Papilionoideae (Faboideae)—Pea family

Common Names

English: yardlong bean, asparagus bean, bodi bean, snake bean, Chinese long bean

French: dolique asperge, dolique géante, haricot kilomètre, haricot asperge

Portuguese : feijão-chicote, feijão-espargo, dólico gigante.

China: dow gauk, dou jiao, chang qing dou jiao, chèuhng chèng dauh gok (Cantonese), ch’eung ts’ing tau kok (Cantonese)

Philippines: sitaw, sitao (Tagalog), hamtak, banor (Visayan), balatong (Ilongo)

Indonesia: kacang belut, kacang tolo

Malaysia: kacang panjang, kachang panjang

Thailand: Tua fak yaow, Tua phnom.

Hmong: taao-hla-chao

Japan: juro-kusasagemae, sasage, juuroku sasage

Vietnam: dau-dau, dâu dûa, dâu giai áo

Description

This is a pole-type bean, growing 3 to 4 m high. The flowers, which are conspicuous and apparently self-pollinated, are borne on short pedicels and may be white, pale-blue, pink, or violet. They commonly open early in the day and close around midday, only to wilt and collapse. The pods can vary greatly in size, shape, color, and texture. They may be linear, curved, or coiled, and normally vary from 8 to 45 cm in length, but can reach 100 cm. They are indehiscent, usually pale green or yellow when ripe, although brown or purple-colored ones can occur. They normally contain 8-20 seeds, which also vary in size, shape, and color. The commonest, however, are white, creamy-white, or black.

These thin, soft beans may grow on delicate stems but they are supported by a tenacious root system. The plant is indeterminate, meaning it continues to grow after flowering and fruiting.

Distribution

Within Africa On the basis of modern evidence, there is no doubt that the cultivated cowpea originated in central Africa from where it spread in early times through Egypt or Arabia to Asia and the Mediterranean. Fifty years ago the British botanist, Burkill, stated that the cowpea reached Sumeria about 2300 B.C. Perhaps that was the first leg of its journey away from Africa. In its new home across the seas, this wandering scion of cowpea took on the new guise of a long, long bean and began masquerading as an Asian food.

Beyond Africa Long bean has been introduced to many lowland tropical countries where often it is a garden vegetable. The plant was taken to the West Indies in the 1500s and reached today’s United States in about 1700. It is popular in the Caribbean and is grown as a summer crop in California, and has become increasingly popular with home-gardeners in the United States. In parts of Europe it is grown especially as a greenhouse vegetable. The crop is produced most widely in the Far East. China and India are both modern centers of long-bean diversity, but unique varieties are to be found in most Southeast Asian nations.

Horticultural Varieties

Dozens, scores, probably hundreds of different types are featured in catalogs of seed companies in worldwide. These are worth trying, although many will differ only in color and other cosmetic features. Varieties from the tropics may be photoperiod sensitive and will not flower under the longer days of summertime in temperate or even subtropical regions.

Environmental Requirements

This warm-season crop can be planted in a wide range of climatic conditions, but is sensitive to temperature and grows relatively slow in mild or cold environments.

Rainfall Long beans easily tolerate drought but the pods shrink and turn fibrous when starved of moisture. All in all, the long-podded varieties require more water than cowpeas grown for seed. Annual rainfall up to 1,500 mm has been recommended.

Altitude Despite claims to the contrary, elevation seems unlikely to limit this crop.

Low Temperature Long beans virtually cease growing when daily maximum temperatures are below 20°C. They must be sown after all danger of frost has passed, and to germinate well the soil should be 20-22°C, otherwise the seeds tend to rot.

High Temperature Long beans prefer high temperature, conditions under which other green beans cannot be produced. Environments with full sunlight attaining daytime temperatures of 25-35° C with nighttime temperatures that stay above 15° C are preferred.

Soil This plant thrives in average garden soil. The plant is a true legume with nitrogen-fixing symbiosis; soil with already too much nitrogen favors leaf growth over pods.