2

BAMBARA BEAN

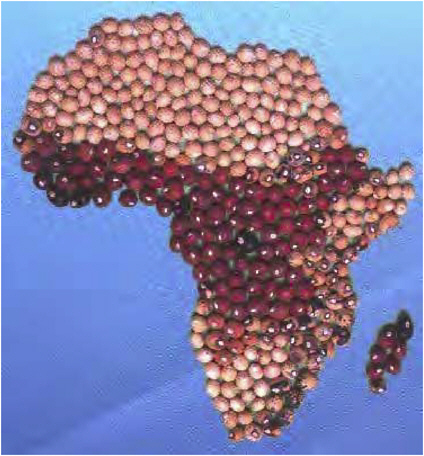

In recent centuries the once-obscure peanut has expanded so dramatically as to become one of the world’s top crops. Of particular importance to Africa, the peanut (there mostly known as groundnut) contributes substantial nutrition to roughly three-dozen nations encompassing two vast belts, one stretching from Senegal to the Central African Republic and the other from Sudan to South Africa. Indeed, considered in continental perspective, peanut is among the largest African food providers—probably coming right after maize, cassava, and sorghum.

What is surprising is that peanut is a Brazilian native that reached Africa’s shores only 400 years ago. And what is even more surprising is that Africa possesses its own counterpart. This local version is similar in virtually every aspect—botanical, agronomic, nutritional, and culinary. Yet while the exotic crop soars to ever-greater heights its stay-at-home cousin languishes almost unknown to agricultural science, food science, economic development, and the world at large.

This African species (Vigna subterranea) is a low-growing legume, not unlike its famous relative in appearance. Often called bambara groundnut, it is conventionally classified a bean, but its seeds are actually dug from the ground like peanuts. To outsiders, only the shape seems unusual: the pods are larger and rounder than peanut shells and the seeds inside are shaped more like peas than peanuts. Those spherical legumes are, however, exceptionally tasty and nutritious. They are also attractive—appearing in varying colors and patterns, characterized by pretty local names such as dove eyes, nightjar, and butterfly.

Like peanut, these native ground beans make a versatile food. Most are boiled in their shells and are offered for sale, ready cooked, on roadsides and in markets. Others are pounded into flour and used in making porridge. Some are boiled with maize meal and used in a relish. A few are also roasted or fried. The flour from the roasted version is especially appetizing and is blended into many traditional dishes.

Although overlooked by the world at large, this is an important resource. Burkina Faso provides a picture of the crop in microcosm. All regions of the

Bambara bean is a low-cost, dependable farm resource that grows in harsh environments where many other crops fail. Production is primarily at subsistence level, and only the surplus is sold. For Africa, the crop offers various benefits, being an ideal subsistence crop, a good rotation crop, a good backstop for hungry times, and a promising commercial resource. (Klaus Fleissner)

country grow bambara bean, producing around 20,000 tons in total.1 Cultivation is exclusively using traditional methods and traditional landraces. Some farmers intersperse the plant among other crops but most grow it in mini-monoculture. Much of the harvest is consumed by the farm family, for whom it is a major source of protein and a lifesaver during the hungry season—the period before the new crops are ready to harvest and the old have been eaten. Beyond this fundamental subsistence use, however, bambara is also a cash crop. Popular with the general public, the fresh beans sell for a premium. There’s never a problem peddling any surplus, and the local sales can constitute the grower’s overall annual cash income.

The question is why does such a valued resource remain largely unknown to agricultural science, food science, humanitarian programs, and economic development policies?

Clearly, the neglect is no reflection of the user’s views. Despite peanut’s spectacular surge, its African counterpart remains a consumer favorite. Indeed, even without the help of science sales are actually edging upward. Today, probably more than 100 million Africans routinely rely on this age-

old resource for at least part of their sustenance during each year. Overall production is around 330,000 tons, about half of which is grown in West Africa; the rest in eastern and southern Africa.2

Clearly, too, the intellectual inattention is not due to any agronomic inferiority. Bambara bean is a dependable food producer, tolerating harsh conditions and growing reliably in challenging locales, including some where other species fail. It is also among the easier legumes to grow: burying its fruits in the soil, it keeps them safe from the myriad flying insects that can devastate or destroy cowpea, common bean, soybean, and other legumes that heedlessly wave their tastiest parts in the air.

Nor is the disregard due to site restrictions. Other than requiring open sunlight and light, loose soil within which to bury its beans, bambara tolerates widely dissimilar substrates, including infertile ones. Indeed, some observers swear it “prefers worn-out soils.”3 Furthermore, this leguminous species fixes nitrogen from the air, thereby insulating itself from Africa’s all-too-common paucity of soil-nitrogen. And beyond all that, the plant thrives in laterite, the reddish acidic soil that is toxic to many crops and is the curse of tropical agriculture.4

Doubts about nutritional performance are not the cause of the neglect either. Ripe or immature, raw or roasted, the seeds pack a load of nutrients. On average, they contain about 60 percent carbohydrate, 20 percent protein, 6 percent oil, and a range of vitamins and minerals. This makes them more like a bean than a peanut. A true quality-protein food, they provide more methionine than other grain legumes, let alone the standard staple cereals.

Despite all these benefits, bambara bean has never been accorded a research program commensurate with its importance or potential. Indeed, it has probably received less than a ten-thousandth the technical support the peanut enjoys worldwide. The neglect is only partly because the plant is stigmatized as a “poor person’s crop”. Rather, it seems largely due to lack of familiarity by those setting the research agenda, especially research donors and agricultural scientists outside Africa.5

Now is the time to open minds and award this native resource a greater chance to catch up with peanut. Given technical support, this resource

certainly can contribute vastly more than it does today. Indeed, the plant has the potential to cut to the heart of Africa’s great humanitarian problems. Consider the following:

Rural development In the lives of the rural poor this low-cost crop is especially important. Many desperate farm families grow it for their own subsistence and also for their annual income. Thus any boost in output or reduction in production costs will disproportionately benefit the group most at risk. Also, commercial food processing is likely to open up buoyant new market outlets. In this regard, it is notable that the canned product seems to have high marketing potential, especially in urban areas. A Zimbabwean company already cans bambara bean, and reports that (except for “baked beans”) it sells as well as any other canned bean—nearly 50,000 cans a year, with sales increasing month after month. Across Africa there is room for many such enterprises, and they will create major markets for farmers and boost income opportunities for rural areas.

Hunger For most of the drier regions bambara bean could contribute to a solid foundation diet. Resilient and reliable, it commonly yields food from sites too hot and too dry for peanuts, maize, or even sorghum. And it produces a food of exceptional nutritional quality, so a little of it goes a long way toward maintaining health.

Malnutrition Compared with peanut, bambara may have a lot less oil and a little less protein, but more carbohydrate and the overall combination nicely balances the food groups. People can live on bambara bean alone, a doubtful proposition even with other legumes. A rare example of a complete food, it could prove a tool for attacking Africa’s chronic malnutrition.

Gender Inequality This bean is mostly produced by women, sold by women, and cooked and served by women. It therefore offers a convenient lever for lifting women up to a better existence. Improve this resource and you improve the lives of millions of mothers, not to mention babies born and unborn. In a related vein, bambara bean offers good opportunities for gender-oriented innovation and commercial development. In the Bida region in central Nigeria, for instance, women make pancakes from the flour and reportedly enjoy a good living selling them. Also in Mali women sell salted bambara nuts, a premium product similar to macadamia nuts and suitable for urban areas and possibly for export as well.

Food Security For much of Africa unpredictable drought is the biggest fear, and this crop might prove an ideal insulator against this periodic shock. Wherever rainfall is unreliable it tends to shine. Bambaras—the people for whom it is named—live in parched, blisteringly hot districts along the

Most seeds pods are picked while still soft and immature; the seeds are eaten fresh or roasted. With a calorific value equal to a quality cereal, this pulse is suitable for use as a staple. As with chickpea and lentil, this legume sustains life. (Werner Schenkel)

Sahara’s southern fringe, and their namesake plant lives up to its etymological heritage.

Sustainable Agriculture Bambara bean epitomizes the current ideal of a “sustainable crop.” Every plot is a mixture of genetic diversity and no plant is fertilized or sprayed. In addition, the species’ nitrogen-fixing capacity helps boost soil fertility, naturally. It can even be used as a soil conditioner. Programs aiming at achieving sustainable farming in Africa could find no better foundation upon which to build their efforts.

Trade Deficits Countries along the southern Sahara have long shipped bambara beans to markets on the Gulf of Guinea coast. Niger is the principal exporter, followed by Chad, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Senegal. Those happen to be among the nations most needful of foreign exchange, and enhancing this particular trade could be part of the answer. Reportedly, the coastal areas have a still unmet demand.6 A similar situation apparently exists in

southern Africa as well. Although Zimbabwe has exported thousands of tons of the dried beans to its neighbors, there is believed to be openings for more.

In sum, bambara bean promises sweeping benefits to the people most in need and hardest to reach through conventional development programs. And despite the almost total scientific neglect, nothing fundamental is stopping this crop from moving on to greater heights.

Of course, technical difficulties deserve attention (as they do with corn and soybean and all crops). These are treated later in the chapter, but it is worth highlighting one example: low yield. Average farm production is now around 400 kg per hectare, yet under improved conditions the crop produces over 4,000 kg per hectare. Farmers today, therefore, achieve merely a tenth of what they could. Clearly, the opportunities for improvement are huge. And the results would be staggering indeed if, in rural areas of hard-pressed countries such as Burkina Faso, ten times more bambara beans could be produced. The effects would in fact be revolutionary.

PROSPECTS

Empirical evidence and preliminary investigations suggest that with attention, bambara could rise to prominence within just the next 20 years. From today’s perspective, that might seem farfetched, but peanut’s stellar performance shows how quickly a newly appreciated resource can ascend.7

Within Africa

Due to its relative resistance to diseases and pests, bambara bean has the potential to improve food security in many rural areas as well as become a stable, low-cost and profitable food crop for Africa’s small-scale farmers. Given the support of good science, conducive government policy, bold investment by food processors, and dedicated local initiative, it could soon be reducing malnutrition and raising both economic levels and human well being.

Humid areas Good. Although details remain sketchy, the plant is capable of growing in rainy areas. However, dampness brings out fungal diseases and means that the plant needs careful handling. Also, the harvest must be made promptly—before the tops have signaled their readiness by turning

|

7 |

Researchers for the FAO, taking bambara as an example of an “underutilized crop,” used weather, soil, and other data to model its potential for growing across Africa and the globe. Their predictions show it widely adaptable to much of the area of peanut and beyond, especially the Mediterranean rim. Azam-Ali, S., J. Aguilar-Manjarrez, and M. Bannayan-Avval. 2001. A Global Mapping System for Bambara Groundnut Production. FAO Agricultural Information Management Series No. 1. FAO, Rome; available online via www.fao.org/documents/. |

yellow. And special provisions are needed to dry the seeds and store them safely.

Dry Areas Excellent. Bambara bean is one of Africa’s most drought-tolerant native legume food crops.

Upland Areas Good. The crop does well in the highlands of Zambia and Zimbabwe. At Gwebi in Zimbabwe, for example, yields of 4,000 kg per hectare have been realized.8

Beyond Africa

Bambara bean is cultivated in Brazil (under the name mandubi d’Angola) as well as in at least two parts of Asia: West Java and southern Thailand. In principle other tropical locations could grow it too. It is said that the crop could produce in the Middle East. FAO studies claim that both Syria and Greece are suitable. Small-scale cultivation trials have been successful in United States, notably in Florida, but no one has yet tried moving it into general production.

USES

Like most legumes bambara bean is used in a variety of ways.

Home Uses As mentioned, in many African countries the pods are boiled and the seeds consumed as snacks. This seems to be the most widespread use. However, in East Africa, the beans are roasted, pulverized, and used as a base for soups that can be either bland or made zesty with added chilies.

Processed Foods Any seeds that reach full maturity turn hard and indigestible, and require boiling and/or grinding into flour to become edible. Such flour is commonly used to thicken and flavor cereal products. In Zambia, it is also made into bread. In Zimbabwe, as we’ve said, bambara bean is canned.9

Another common practice is to crush the dried seeds into a paste. Various fried or steamed products made from this are very popular in Nigeria and neighboring nations. One, called akara,10 is a form of bean fritter that is frequently sold on the street and is especially common at bus stations.

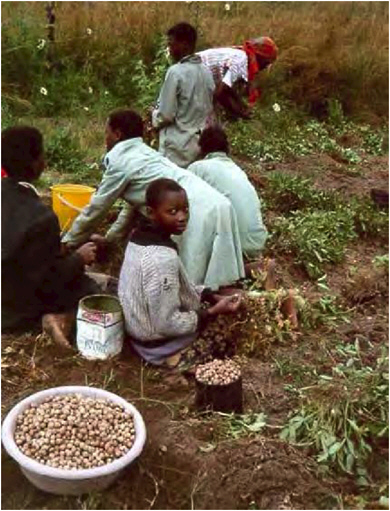

Manzini region, Swaziland. The family of Mrs. Fakudze (at back wearing headscarf) helps harvest the bambara crop. Like peanut, the plant forms pods and seeds underground. Unlike peanuts, the seeds are round, smooth, and very hard when dried. Among the most adaptable of all crops, it tolerates harsh conditions and yields food in droughty sites where peanuts, maize, or sorghum fail. (Karen Hampson)

Another, called moin-moin, is a sort of savory bean pudding. Yet a third, okpa, is a doughy paste that is wrapped in banana leaves and boiled. These age-old favorite “fast-foods” are mainly made with other beans, but those made from bambara are considered the best.

Oilseed With an oil content of only around 6 percent, bambara bean would seem to make for an unlikely oilseed, but reportedly some peoples in Congo pound the roasted nuts and separate the liquid for cooking.

Animal Feed Bambara beans have been fed to chicks with great success. The leaves, which are rich in protein and phosphorus, make useful livestock fodder. The haulm (stems, leaves, and other crop residues) is palatable, rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, and is also highly suitable for grazing animals.

Medicinal Use Among beans this one is said to have the highest concentration of soluble fiber, a non-nutrient famously occurring in oatbran and believed to reduce the incidence of heart disease and to help prevent colon cancer.11 In addition, the crop has medicinal uses in many areas in Africa. In Botswana, for example, the black seeded landraces have the reputation of being a treatment for impotence.

Other Uses By contributing nitrogen to the soil the living plant is a good companion in crop rotations.

NUTRITION

Ripe or immature, the seed averages 63 percent carbohydrate, 19 percent protein, and 6.5 percent oil.12 The protein, as formerly noted, contains more of the nutritionally essential amino acid methionine than that in other beans, making it more complete.

The seed has the reputation of being very filling. And no wonder: its nutritional energy (per 100g) has been measured at 367-414 calories, an amount greater than that of common pulses such as cowpea, lentil, and pigeon pea.13

Although formal infant-feeding studies are unreported, a trial has been conducted of “milks” prepared from bambara bean, cowpea, pigeon pea, and soybean.14 Whereas all were declared acceptable, the scientists ranked bambara-milk first in flavor, nutritional value, and color. The mothers and (seemingly) their babies preferred it too.

HORTICULTURE

The plant comes in two basic shapes: a sprawling, ground-hugging type and a more upright, “bunched” or bush type that stands erect. The former is grown exclusively by smallholders as a subsistence crop; the latter is the one planted in larger-scale farming. Because there are no formal varieties, all

plantings involve mixtures of landraces selected during traditional production.

So far, there are no standard methods for handling the crop. Speaking generally, it is produced like peanut. Most farmers sow early in the rainy season, usually dropping two to four seeds into a hole about 5 cm deep, and covering them with soil. Planting density is normally low, especially when the planting is not organized in rows. The literature gives the optimal spacing as anything from 40x25 cm to 60x60 cm. Given the mixture of seeds emergence is necessarily variable, extending from 7 to 21 days.

The crop is most often sown in the family’s main field (rather than its kitchen garden), frequently being tucked into the corner of the maize or sorghum plot. Some farmers use ridges or mounds. As with peanut, they “hill up” the plants.

Soil is the key to success: It must be loose and loamy enough for the pegs to penetrate. Those fragile flower stems emerge from the base of the pealike yellow blooms, elongating until they meet the soil below. Once they’ve pushed below the surface, the tips swell and the seeds begin forming. As the seeds mature below ground, the aboveground parts gradually lose their vivid-green vitality and turn yellow, a signal that the seeds are ripe for digging.

Given that fertilizer is uncommon in Africa, this crop’s requirements are unrecorded. In West Java, the one place where farmer practice has been detailed, urea is sometimes sprinkled around the young plants. In southern Thailand, where soil fertility is quite low, any available fertilizer is applied as a side dressing along the rows at rates up to 150-300 kg per hectare.

HARVESTING AND HANDLING

Like peanut, bambara bean develops slowly. Depending on climate and cultivar it may take anything from 90 to 180 days to mature. Most of today’s main types are ready to harvest in 130-150 days, or about 2 months after the pods first appeared.

In the dry zones, the timing of the harvest is less critical than with peanuts; bambara beans can be gathered early or late without serious loss. However, if they are to be used as snack, they must be harvested just before the leaves begin yellowing. And in humid areas prompt harvest becomes vital because seeds left in the warm damp soil can rot or germinate.

To harvest the crop, the whole plant is pulled up. With the bunched-type, most pods remain attached to the root crown. The per-hectare yield is generally 300-600 kg of dried seed. As we’ve said, much better production is possible: Six independent trials in several Central African countries recorded yields in excess of 2,000 kg of shelled seeds per hectare.15 A 1969 report from Ukiriguru Experiment Station in Tanzania recorded yields up to

2,600 kg per hectare. Various other documents refer to experimental yields in excess of 3,000 kg per hectare. And in West Java yields of 5,000-6,000 kg per hectare are recorded.

Freshly harvested pods are typically left in the sun several days, during which time they shrink, darken, and dry out. After threshing to separate the vegetable matter, the harvest is marketed either as pods or as seeds.

In storage, shelled bambara beans are susceptible to bruchid beetle. The pods, however, are extremely resistant. Farmers therefore keep their seeds for planting in the unshelled form.

LIMITATIONS

On the agronomic front, the lack of varieties with stable and predictable yield is the main concern. Formal attempts at breeding have so far been unsuccessful. Every planting therefore now employs landrace mixtures, and plants in a single field differ wildly in appearance, performance, and product.

A point that has only recently been recognized is that the crop—or at least some of its types—is photosensitive.16 This could explain why some cultivars mature exceptionally late. Photosensitivity can be a two-edged sword. On the positive side, it can ensure that certain types mature at exactly the right time (usually the end of the rains) for a given location. On the negative side, it can restrict the seeds to that same location and to a single planting time each year.

The plant nodulates freely. Specific Rhizobium strains can boost its growth far above normal (with average strains), but as of now those select strains are poorly characterized and the farmers are not benefiting much from them.

Despite its general robustness, this plant can fall victim to fungal disease (notably fusarium wilt and leaf spot). Usually this occurs only when and where the conditions are unusually damp. On the other hand, viral diseases are widespread across many environments, especially where cowpea and other grain legumes are grown.17 Also, even when hidden below ground the seeds are not entirely beyond danger: Rodents, crickets, and (in especially dry weather) termites can be problematic. In sandy soils nematode infestations can be bad.18

The pegs seldom penetrate far, which is why the farmers “hill” soil over them. Any that stay exposed to sunlight tend to turn green and to develop improperly.

The crop has potential for large-scale production, but under the rigors of

mechanical harvesting the current types tend to “shatter” (drop their pods). A related problem is the lack of a mechanical sheller.19

Although genetic diversity can be a selling point and perhaps an insurance policy, it hinders large-scale operations. Because of its diversity, for instance, bambara bean cannot be processed using a consistent formula and some consumers are put off. When you get right down to it, a bean of variable texture and taste has difficulty competing with the super-consistent Michigan pea bean, for example, all of which are identical in size, color, taste, and texture.

One serious limitation is the time needed to cook the dry seeds. Wherever firewood is scarce, this can pose a problem.

The seeds reportedly contain “flatus factors,” which like their counterparts in common beans reduce, but don’t eliminate, the food’s desirability. A good 24-hour soak is said to reduce the effect.

NEXT STEPS

With a crop as neglected as this, almost everything needs doing. Following is a selection.20

Building a Bigger Market We are confident enough of the bambara bean’s basic qualities to recommend that the first focus be the output end. Opening up opportunities for sales will produce an explosion of grower interest and almost automatically result in greater planting, greater research, and greater recognition all round. Opportunities for increased sales could be in the formal and informal sectors, urban centers, rural centers, exports, and commercial food processing. For farmers the key issue will be price. If they can achieve the same returns they get for other premium beans, this crop will emerge from hiding all across the continent.

The key to higher prices is strengthened demand. And marketing campaigns are one way to strengthen demand. This commodity above all else needs publicity. Even in tropical Africa, millions remain unaware of its existence, let alone its benefits. The information should be aimed especially at urban areas and the younger generation. It should be a typical consumer-awareness venture (not excluding endorsements by local celebrities). Adjuncts in this case might include recipes in various local languages and special dishes served in fancy restaurants and state dinners.

Processing can also help break through mental barriers. According to one

|

19 |

In this regard, a mechanized bambara-groundnut sheller is reportedly under development in South Africa. |

|

20 |

Other research ideas and a comprehensive review of this crop, including bibliography, can be found in Heller, J., F. Begemann, and J. Mushonga, eds. 1997. Bambara groundnut: Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome; available online via www.ipgri.cgiar.org/publications. |

reviewer, Zimbabweans formerly viewed bambara bean as a famine food, fit for eating only as a last resort. However, when it became available in cans all that changed. Suddenly, it was seen as modern.

Any publicity campaign might be extended internationally. To consumers in North America or Europe canned bambara bean will look much like other canned beans. But it will take on a new mystique once they know that: 1) it was grown by impoverished women farmers, 2) it was grown organically, and 3) every purchase helps preserve an ancient heritage of biodiversity. The future could perhaps see a movement not unlike those aimed towards fostering shade-grown coffee or rainforest candies.

International food-relief agencies could help as well. Using local bambara instead of importing foreign beans would stimulate farmer interest, consumer confidence, and overall production.

In a related vein, the publicity programs should aim at broadening the crop’s uses. In eastern and southern Africa, for instance, it is currently viewed as a snack food. Extending its use to include the main-course dishes will see hundreds of thousands of small farmers substantially increase production, profits, and prospects.

In modifying people’s mindsets, it is important to develop better figures on the present production. One of our reviewers urges that governments stop burying bambara bean under “Other Pulses,” and include it separately in their national agricultural statistics. This will, he says, enhance the crop’s reputation and status in policymaking and development programs.

On-Farm Promotion Parallel to the public-awareness promotions, there needs to be farmer-awareness activities. Currently, many farmers don’t plant bambara bean solely through lack of knowledge, confidence, or advice. In parts of its range, the limit is merely a lack of quality seed. Governments and seed suppliers should rectify this by multiplying whatever reasonable landraces are on hand. Also, extension agents should encourage farmers to set aside areas for producing bambara-bean seed for themselves and their neighbors. Although NGOs, commercial organizations, and extension services should assist in seed multiplication, farmer-to-farmer exchange programs could prove especially good mechanisms for upgrading this crop.

Genetic Resources and Breeding The genetic diversity needed to improve bambara bean is already on hand. Collections have been made across Africa, and the resulting seeds remain securely stored in facilities across Africa.21 Therefore, in the long process of improving this crop, one

starting point is this germplasm. Having come from different parts of the continent these seeds should demonstrate the genetic treasures within this species. Then, through judicious selection and breeding, the road to cultivars possessing broad adaptation to Africa’s various environments ought to open up.

The plant’s underground flowers make cross-pollination difficult, but attempts are nonetheless being made to breed in desirable characters, particularly high and stable yield, early maturation, and photo-insensitivity. These are important actions, but more are still needed to ensure that the crop moves forward with a broad-based and reliable genetic underpinning. They plants are self-compatible and largely self-pollinated (though ants may help increase pollination levels), so once a variety is found it should stay reasonably stable.

In part, parallel crop breeding activities are necessary because bambara bean occurs throughout Africa and occupies a vast array of different sites. Though this suggests a highly adaptable plant, there are indications that individual cultivars are site-specific. Tanzanian cultivars, for example, have yielded poorly in Zambia. Indeed, some from northwestern Tanzania failed in the drier climes and different soils of central Tanzania. For starters, the most effective research on improving this crop may be to concentrate on local landraces.

However, it is also important to separately sort out the photoperiod effects, and to create day-neutral types that will grow in different latitudes and seasons. Shuttle breeding could be the key to long-term success, as it was with the wheats that created the Green Revolution in Asian and Latin America. Moving seeds sequentially from location to location and discarding all but the best producers at each site quickly distinguishes the most resilient and adaptable types.

In part, too, parallel crop breeding activities are needed to produce different plants for different farming styles. Types suitable for large-scale mechanized farming are needed on the one hand, and types for small-scale cultivation by subsistence farmers on the other. It has been suggested that the targets be: a bunch ideotype for large-scale mechanized farming and a spreading ideotype for smallholders dependent on cereal-based subsistence systems where the plants are more scattered.

Although we’ve noted that adequate genetic diversity is on hand, more collections are needed on farms in Burkina Faso, Togo, and Nigeria’s middle belt—a zone thought to include the greatest variation. Further, there is a need to collect the ancestral, pre-domestication wild form that is distributed in natural areas from Jos Plateau and Yola in Nigeria, to Garoua in Cameroon, and probably beyond.

Horticultural Development Given the almost complete lack of tested information, the crop’s agronomy deserves intensive study. This doesn’t, however, demand a delay for research investigations: enough expertise already exists to raise the crop’s productivity many-fold and quickly.

Part of that expertise is stored in the minds of Africa’s farmers, and there is a need to assess their practices and adapt the best Africa-wide. On the other hand, part of that expertise is stored in the minds and manuscripts of peanut researchers who have no inkling their crop has an African cousin, let alone that their experience could help it. Peanut research is prominent in the United States, Brazil, Australia, and several African nations. Researchers there should include exploratory studies with the bambara bean. In this way, they will likely see how to quickly lift levels of production and utilization. As a bonus, they might reap powerful insights into the peanut plant.

In particular, the crop’s management on a larger scale needs advancement. Investigations of mechanized cultivation and harvesting, and the overall adaptation of modern peanut-farming methods should be undertaken. Investigations into mechanized shelling and processing (especially canning) are more than justified. A machine to crack open pods could do more than almost anything to advance thie crop.

Although bambara bean is relatively free of pathogens and pests, research to identify cultivars more resistant to the major known threats could be most helpful. Trials should be made in ecological zones rife with the particular disease or pest. It is there that the plant’s ultimate adaptability and resistance can best be determined.

Unconfirmed observations indicate that the crop can suppress striga, a parasitic weed particularly prevalent in Africa’s sandy soils. In addition, as we’ve noted, the plant is said to thrive in laterite, the reddish acidic soil that is rich in soluble aluminum and toxic to many crops. And the crop reportedly does very well in sandy soils. Each of these capabilities deserves rapid assessment and promotion because each would be great value to Africa, just by itself.

Nutrition and Food Technology Nutritionists and food technologists— whether inside Africa or not—should pay close attention to this overlooked food plant. Huge gaps in the knowledge base still remain to be bridged.

For one thing, the micronutrients—both vitamins and minerals—need careful documentation.

For another, the overall digestibility needs checking. Antinutritive factors are likely to be present, and their levels during different stages of seed maturity need assessment. In addition, their fate during various types of cooking should be followed. Finally, their levels in different seed types need measuring.

For a third, aflatoxin levels should be assessed on bambara bean samples.

Given this cancer-causing chemical’s threat to the safety of peanut, this would be a wise precaution.

Beyond those fundamentals, this food needs testing in programs engaged in fighting malnutrition. At least one researcher has suggested it could form the basis for special dietetic foods for children. In as much as the crop grows in some of the most malnourished nations, this should be followed up. Interesting in this regard would be head-to-head comparisons with soyfood counterparts.

As we’ve noted, the crop could find use in food industry. Processing methods such as canning, milling, popping, puffing, and protein extraction might lift it into many new markets. Snack foods are a special possibility. Possibilities for such processed foods in world trade should be considered.22

For such large-scale operations, the option of packaging boiled beans in pouches should be considered, as it might avoid the expense of metal cans. Solar heating and storage under anaerobic conditions (e.g. in sealed metal drums or plastic bags) could be effective ways to reduce post-harvest losses.

As noted, too, at least some seeds contain flatus factors. The levels of poorly digested sugars should be checked in a range of different strains. It’s possibly a long shot, but it might lead to breeding lines with elevated digestibility and greater consumer acceptance.

The fact that the seeds are rich in soluble fiber deserves follow up. Other crops containing such substances are widely touted to reduce the incidence of heart disease and help prevent colon cancer. Psyllium and oats have turned into major international resources solely on the basis of possessing this same non-nutritious nutrient. Might a new bambara bean export line be developed around it too?

SPECIES INFORMATION

Botanical Name Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.

Synonyms Voandzeia subterranea (L.) Thouars.

Family Leguminosae Subfamily: Papilionoideae

Common Names

Afrikaans: dopboontjie

Arabic: gertere, guerte

English: bambaranut, bambara groundnut, Congo goober, earth pea, baffin pea, Njugo bean (South Africa), Madagascar groundnut, ground bean, earth bean, earth nut

French: voandzou, pois d’Angole, haricot pistache, pois arachide, pois

Bambarra, pois Souterrain, vanzon,

Portuguese: mandubi d’Angola (Brazil)

Sierra Leone: agbaroro (in Creole)

Ghana: aboboi, akyii

Nigeria: epi roro, guijiya, gujuya, okboli ede

Hausa: juijiya

Ibo: okpa otuanya

Yoruba: epi roui

Sudan: ful abungawi

Central Africa: njogo bean

Kenya: njugu mawe

Zambia: juga bean, ntoyo

Malawi: nzama, njama

Zimbabwe: nlubu, nyimo, jugo bean

Madagascar: pistache Malagache, voanjobory

Ndebele: indlubu, ditloo

Shona: nyimo

Swahili: njugu, njugu mawe

Tsonga: kochane, nyume, ndlowu

Venda: nduhu, nwa, tzidzimba

Xhosa: jugo

Zulu: indlubu

siSwati (Swaziland): tindlubu

Indonesia: kachang Bogor,

Thailand: thua rang

Malaysia: kachang Manila (Manila bean), kachang tanah, nela-dakalai

Surinam: gobbe

Description

The plant is a herbaceous annual, often spreading or trailing, but also erect and bushy. It has a well-developed taproot with profuse geotropic lateral roots. New roots often appear where nodes contact soil. The fibrous lateral roots form nodules for nitrogen fixation. In association with appropriate rhizobia they usually nodulate well.

The stems are branched and hairy, with short internodes. The leaves are trifoliate and are borne on long slender petioles. The flowers spread out close to ground level on hairy peduncles, each producing one to three flowers. Most flowers are light yellow in color, although some are deep yellow (especially late in the day). After pollination, each small flower sends down a tendril, or peg, like a long root, which continues to burrow even after it has pierced the soil.

Like peanut, the plant then forms pods on, or just beneath, the ground. The pod achieves its mature size about 30 days after fertilization. The seed further develops in the subsequent 10 days. Most varieties have single-

|

BAMBARA BEAN BEYOND AFRICA Bambara bean was known in Brazil as early as the 1600s, and its origin is clear from its name: mandubi d’Angola. Portuguese voyagers—most likely slavers—carried it across the Atlantic. Many crops were carried both ways between Brazil and today’s Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Principe and Sao Tome. Indeed, from those germplasm swaps Africa received peanut, cassava, and maize— the three main foods that now feed the continent. By a historical accident, the first botanical mention of the crop was by Marcgrav de Liebstad, who recorded it as a native Brazilian crop in 1648. Then for another 158 years the crop was lost to the literature. It was only in 1806 that another botanist (Du Petit-Thouars) stumbled across the same species growing in Madagascar, under the name voanjo. Following that rediscovery, it took about another century of botanical sleuthing to finally confirm that the plant was truly African. In addition to Brazil at least two parts of Asia—West Java and southern Thailand—also cultivate the crop. Although produced only on a micro scale, this African legume serves Indonesian and Thai consumers as a soup vegetable, a snack, and a dessert ingredient. How and when it reached Southeast Asia has so far not been explained. In Malaysia, where the plant is known as kacang poi, it is mostly consumed as boiled nut (similar to peanut). Perlis, Kedah, and Kelantan, states bordering Thailand, are apparently the only ones to grow it so far. The crop is produced like peanut, but is said to yield less. It is commonly marketed as raw nuts at farmers and night markets. In addition, small amounts are imported from Thailand. |

seeded pods, but ecotypes collected in Congo frequently had pods with three seeds.23 Mature pods are indehiscent, often wrinkled, ranging from a yellowish to a reddish dark brown color. The seeds are round, 1-1.5 cm in diameter, and come in colors varying from white to creamy yellow, brown, purple, red, and black. Most are a single color, but some are mottled, blotched or striped.

Distribution

Within Africa Although wild types are still to be found in tropical eastern Africa, the crop is believed to have originated in the region encompassing northeastern Nigeria and northern Cameroon. It is today

cultivated throughout tropical Africa’s drier areas, including Madagascar. In southern Africa, Zimbabwe is the center of production.

Beyond Africa Botanists in earlier times identified specimens in a number of tropical locations, including India, Philippines, Fiji; Sri Lanka, New Caledonia, and Surinam. Whether the plants still exist there is unknown; probably they were in botanic gardens and research institutions, rather than farmers’ fields.

The present degree of cultivation outside Africa is basically negligible. However, the crop still grows in Brazil as it has since the 1600s. It is also cultivated in West Java and southern Thailand. Although produced only on a small scale, this African legume serves Indonesian and Thai consumers mainly as a soup vegetable, a snack, and a dessert ingredient.

Horticultural Varieties

Strictly speaking, there are no formal varieties. Every planting now uses mixtures of landraces mainly identified by the size and color of the seed and the shape of the leaf.

Environmental Requirements

The plant grows best in climates used for growing peanuts, maize, millet, or sorghum. It needs abundant sunshine, high temperatures, at least four frost-free months, and frequent rains during the period between sowing and flowering.

Daylength Most cultivars are adapted to short days of the tropical and subtropical latitudes.

Rainfall An evenly distributed rainfall in the range 600-1,000 mm encourages optimum growth, but satisfactory yields can be obtained where the dry season is pronounced. Except during the flowering period, heavy rainfall causes no problems.

Altitude Satisfactory yields can be obtained at elevations up to at least 1,600 m.

Low Temperature For optimal growth the temperature requirement is reported as 20-28°C.

High Temperature The plant seems little fazed by high temperatures. It grows, for instance, where temperatures top 40°C; areas, in other words, unsuitable for many leguminous crops.

Soil The crop must be planted in loose, light soils to facilitate both the nitrogen-fixing bacteria in its root nodules and the development of the buried seeds. It also eases the task of digging up the pods. Any well-drained soil is suitable, but light sandy loam with a pH of 5-6.5 and medium to low fertility is said to produce the most seeds.

Related Species

A closely similar plant, the groundbean or Kersting’s groundnut,24 also deserves attention. Its leaves are broader than those of the bambara bean and the plant is less robust. Though the pods develop underground, the seeds resemble common beans and are usually white, brown, black, or speckled in color. Their protein occurs in good quantity (19-20 percent) and is rich in the essential amino acids lysine (6.2 percent) and methionine (1.4 percent). Grown in both high-rainfall and savanna areas in tropical Africa, this groundbean survives even drier areas and is even more obscure than the bambara bean. Although the seeds are tasty, they are small and yields are poor, disadvantages likely to be correctable with appropriate research. Achieving that could unleash a high-lysine, high-methionine crop of potentially great nutritional significance.

Another virtually unknown relative is found in tropical Africa is Vigna poissoni (synonym Voandzeia poissoni Chev., also a synonym for, at least, some forms of Kersting’s groundnut). Its underground beans are supposedly eaten in Benin, but we are unaware if even one agricultural or food scientist has looked into this species yet.