3

Containing the Tobacco Problem

The trends in cigarette smoking charted in Chapter 1 reflect the push and pull of social forces that tend to promote tobacco use and those that tend to reduce it. Tobacco use in the United States dates back to before colonization, and it has probably had its detractors almost as long. This chapter reviews public health efforts to contain tobacco use over the past four decades. It is not meant to present a nuanced account of the economic, political, and social forces that have shaped the nation’s response to tobacco use over this period. Fortunately, interested readers can find the full story in recent books by Richard Kluger and Allan Brandt (Brandt 2007; Kluger 1997). The brief review presented below is designed to highlight key features of the story as seen through the lens of public health.

The introduction of mass-produced, finished cigarettes in the 1880s was followed by mass marketing campaigns that have made cigarettes one of the most highly promoted products in the nation’s history. As the appeal of cigarette smoking grew, however, so did the strength and vehemence of the antitobacco activists. Some opponents had moral or religious objections to smoking, and they and others decried its presumed health dangers in the context of a contemporary populist health and hygiene movement. Cigarettes were called a “poison” and even “coffin nails” during those anti-tobacco campaigns (Burnham 1989; DHHS 2000; Tate 1999).

The antitobacco activists claimed some victories in the early 20th century, including the passage of laws in several states that prohibited tobacco use by both adults and minors (DHHS 2000; Outlook 1901). Their gains, however, were short-lived. Smoking was becoming embedded in the American culture. Cigarette use among soldiers in the Civil War—as in

wars to follow—helped promote its popularity and respectability (DHHS 2000). There was no medical consensus regarding health dangers; in fact, many physicians openly smoked and sometimes even promoted the product (DHHS 2000; Walsh 1937). The anti-tobacco forces were unable to stem the growing popularity of cigarettes over the first half of the next century (DHHS 2000; Schudson 1984).

By the middle of the 20th century, researchers were studying the health effects of smoking. In 1952, an article in Reader’s Digest reporting on the emerging evidence linking smoking and cancer aroused public concern (Norr 1952). More than 10 years later, publication of the 1964 Surgeon General’s report (HEW 1964) was widely regarded as a turning point in the history of smoking in the United States and the point of departure for the modern tobacco control movement (DHHS 2000).

The 1964 report consolidated the growing body of research that linked smoking to lung cancer, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema, disseminating the emerging data on tobacco’s adverse effects to a wide audience (HEW 1964). The report’s authoritative voice—the Surgeon General is the country’s top health officer—and compelling documentation were impossible to ignore. The steady growth in smoking prevalence that had begun in 1920s came to a halt.

After publication of the report, public debate over smoking could never again be divorced from its documented adverse health effects. Smoking could no longer be viewed exclusively as a matter of consumer choice based on the idea that tobacco is an ordinary consumer good. Smoking had officially become a medical problem and a public health challenge. As the 1964 report stated, “cigarette smoking is a health hazard of sufficient importance in the United States to warrant appropriate remedial action” (HEW 1964).

The Surgeon General’s report stimulated a significant change in public attitudes about smoking and new public health and public policy responses. The story of the past four decades, however, is not one of unmitigated public health success. The decades following the report’s release can be divided into two periods. The first phase, which lasted through the late 1980s, was characterized by largely unsuccessful efforts by those involved in the antismoking movement to gain political footing against the tobacco industry, a commercial giant with many tools at its disposal. Beginning in the mid-1980s, however, the understanding of the tobacco problem and the tools used to combat it underwent dramatic transformations. Smoking came to be recognized as a form of drug addiction, one that typically begins by the age of 18 years and that is fostered by the marketing and other actions of cigarette companies. In addition, the harms that smoking causes to nonsmokers, as well as smokers, also changed the political landscape of tobacco control efforts.

PUBLIC HEALTH TAKES ON THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY: 1964–1988

The initial declines in smoking following the release of the 1964 Surgeon General’s report came largely from motivated smokers quitting in response to the highly publicized and frightening findings about tobacco’s dangers. With some 70 million tobacco users in the country and with so many Americans—from farmers, factory workers, and cigarette manufacturers to retailers, advertising agencies, and the media—tied economically to smoking, however, dramatic political change did not occur overnight. Moreover, in the turbulent 1960s, the country’s attention was focused on such pressing political issues as civil rights, Vietnam, and the War on Poverty (Kluger 1996).

Educational Initiatives

Public education was the first line “remedial action” taken in response to the Surgeon General’s call. The American Cancer Society was an early leader. Other voluntary health groups, such as the American Lung Association and the American Heart Association, with their core missions of public education, were also well positioned to take early leadership roles. The three groups worked independently of one another until 1981, when they formed the Coalition on Smoking OR Health. State and local leaders of these organizations began to form similar coalitions in their areas, extending the antismoking effort in states and local communities (DHHS 2000). The American Medical Association (AMA) did not become an advocate for tobacco control until the mid-1980s, when Board of Trustees member Ronald Davis urged the AMA to testify before Congress (Kluger 1996).

New programs to aid in smoking cessation and prevention were developed and implemented. The 1960s saw a rapid introduction of new behavioral approaches to smoking cessation, with novel ideas appearing almost every year. By the 1980s, pharmacological approaches were attracting attention. The National Cancer Institute’s Smoking and Tobacco Control Program was a major source of research funding (Shiffman 1993).

School-based prevention programs were also developed and introduced in the 1970s and 1980s, sometimes as a part of alcohol or other substance abuse programs. These programs used a variety of approaches, which varied on the basis of local preferences. Later, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued its Guidelines for School Health Programs to Prevent Tobacco Use and Addiction to provide a national framework and impetus for these programs (CDC 1994).

It took time for antismoking coalitions to coalesce, but anti-tobacco advocacy and grassroots efforts came to play a key role in containing the

tobacco problem. A notable early development came in 1966 when John F. Banzhaf successfully petitioned the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to invoke the Fairness Doctrine and mandate reply time on television and radio for the cigarette commercials glamorizing smoking. This action ultimately led to an FCC requirement, beginning in 1967, that stations run one free counter advertisement from health groups for every three cigarette commercials that they aired. The American Cancer Society, working with top advertising agencies that donated their time, took the lead in producing graphic and compelling counter advertisements. Banzhaf went on to form Action on Smoking and Health, a national antismoking consumer organization that was reported to have 60,000 members by 1979 (Kluger 1996).

Congressional initiatives gave some support to the public education efforts, giving what seemed to be at least a symbolic win to the nascent tobacco control movement. Within a year of the publication of the Surgeon General’s report, the U.S. Congress passed the Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1965, which required cigarettes packages to contain the message “Warning: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous To Your Health” (CDC 2005).

As additional scientific evidence documenting the dangers of smoking continued to emerge, the 1969 Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act upgraded the warning to read “Warning: The Surgeon General Has Determined That Cigarette Smoking Is Dangerous To Your Health” (CDC 2005). The law also banned all cigarette advertising on television and radio, effective January 1, 1971 (Borio 1993).

By 1981 a Federal Trade Commission (FTC) staff report had concluded that the health warning on packages was “worn out” and was having little impact on public knowledge and attitudes about smoking. The warning was too abstract and difficult to remember, and it was not seen as personally relevant (Hinds 1982). Congress responded with the Comprehensive Smoking Education Act of 1984, which required the use of four, more specific, labels on cigarette packages and cigarette advertisements that would be rotated on a regular basis (CDC 2005).

The new warnings reflected the steady flow of research findings tying smoking to increasing numbers of serious conditions. By the time that the 1989 Surgeon General’s report was released, the list of conditions that scientific studies had linked to smoking included various cancers—including lung, laryngeal, oral, and esophageal cancers—as well as pulmonary disease, heart disease, and fetal growth retardation. This growing body of research helped power the tobacco control movement.

The Tobacco Industry’s Response

Even as public health forces were coalescing and making policy inroads, the tobacco industry was fully engaged as a formidable opponent. Tobacco

has been entrenched in American society for so long that it is extremely difficult to sort out the precise roles of various commercial, medical, social, and cultural forces in sustaining the tobacco problem. The tobacco industry’s forceful strategies, however, have provided a powerful counterforce to the public health effort. As the 2000 Surgeon General’s report would later state, in admittedly simplified terms: “The history of tobacco use can be thought of as a conflict between tobacco as an agent of economic gain and tobacco as an agent of human harm” (DHHS 2000).

The medical establishment was initially slow to embrace the imperatives of the growing findings about smoking and heath. The tobacco industry, on the other hand, quickly sprung into action in the early 1950s to counter the studies connecting smoking to higher mortality rates. In the late 1950s, cigarette manufacturers created the Tobacco Institute, which claimed to represent not only cigarette producers and distributors but also hundreds of thousands of farmers and others with economic interests in tobacco (Kluger 1996). The Tobacco Institute was the driver of the industry’s extensive public relations and lobbying campaigns for decades. It sought to underscore the economic importance of tobacco and, together with the industry’s Council for Tobacco Research (initially called the Tobacco Industry Research Council), to undermine the scientific evidence identifying the risks of smoking and documenting its effects on health. By disputing the scientific findings about the dangers of smoking, the industry sought to reassure its customers and to obscure the public’s understanding of the risks.

The industry also assertively sought to counter and displace the message about the dangers of smoking with a message tapping into the American spirit of individualism, freedom, and unease with government paternalism. The industry’s message was simple: Smoking is an individual’s free choice and no one else’s business and certainly not the government’s business.

Although the voluntary health organizations leading the early public education effort tended to avoid controversy and politics, tobacco interests built a powerful presence on Capitol Hill. They sustained their influence by lobbying, making campaign contributions, and building allegiances with members from tobacco growing states, many of whom held key leadership positions (Kluger 1996).

Through their efforts, tobacco industry advocates were able to influence key legislation. For example, Congress denied the Consumer Product Safety Commission jurisdiction over cigarettes, reversing the position taken by the agency’s first chairman, who said that the commission had authority to regulate or even ban cigarettes. Tobacco was also expressly exempted from regulation under the Toxic Substances Control Act (1976), even though the law was intended to regulate chemical substances which present “unreasonable risk of injury to health of the environment.” Although the nicotine in tobacco is highly addictive, tobacco is also explicitly exempted

from regulation under the Controlled Substances Act (1970). Without these congressionally enacted exemptions, tobacco products would have been subject to strong regulation—indeed, they theoretically could have been removed from the market under these statutes if the applicable regulatory agency had been so inclined (Kluger 1996).

As they sought protection from potentially damaging legislation, tobacco companies also spent billions of dollars marketing cigarettes to ensure a steady stream of customers. Their products were killing some 400,000 people a year and causing widespread morbidity, while the public health community scrambled to stem the damage. The major companies, aggressively competing for market share and for new smokers, hired top public relations companies to reshape the image of old brands and draw in new populations of smokers (Kluger 1996).

With women accounting for an increasing proportion of smokers and with the women’s liberation movement advocating for female freedom and independence, women became a ready target for tobacco industry marketing. In 1967, companies rapidly increased their advertising in women’s magazines and Philip Morris launched its Virginia Slims cigarette featuring the memorable slogan “You’ve Come a Long Way Baby.” The rate of smoking initiation among girls younger than age 18 years rose abruptly in 1967, the year that the Virginia Slims campaign began, peaking in 1973 at more than double the rate in 1967 (Pierce et al. 1994).

By the late 1980s, the R.J. Reynolds Company recast its Camel cigarette brand with a cartoon figure, Joe Camel, and initiated a marketing effort that would prove especially popular with young people. Following this image redesign, Camel’s youth market share ballooned. Although the tobacco companies insisted for decades that they were not targeting underage smokers, industry papers that would later become public indicated otherwise (Kluger 1996).

The tobacco companies also competed for smokers who were concerned about the dangers of smoking by marketing a succession of new low-tar and “light” cigarettes that offered smokers an alternative to quitting. These products emit lower levels of tar, carbon monoxide, and nicotine than other cigarettes, as measured by the standard FTC machine testing method. The implication that low-tar cigarettes would therefore reduce the dangers of smoking made these products the choice of increasingly large numbers of customers. Research later showed, however, that the benefits of low-tar products are not what the FTC figures might suggest, because smokers alter their smoking patterns to compensate for the reduced nicotine delivery and because the standard smoking machine used by the FTC does not accurately simulate how smokers smoke. Therefore, people who switched to these brands did not significantly lower their health risks (Harris et al. 2004; IOM 2001; NCI 2001).

Companies also turned their attentions internationally, as free trade agreements and the collapse of communism in the late 1980s opened markets in Asia and Eastern Europe that previously were controlled by local monopolies. The big international tobacco companies introduced marketing campaigns in countries that until then had not seen extravagant cigarette advertisements, due to the state previously controlling all tobacco sales. The introduction of more varied and better-tasting American cigarettes, sometimes cheaper thanks to market competition, exported the tobacco problem to developing countries, even as rates were declining in the United States (Sugarman 2001). As a result, more than 95 percent of the world’s smokers now live outside the United States. According to World Health Organization projections, by the year 2020, 10 million people will die annually from tobacco-related illnesses, and 70 percent of these individuals will be in developing countries (WHO 2005).

Even when Congress passed legislation that seemed to promote the tobacco control effort, the public health gains often turned out to be illusory. The 1965 health warning legislation, for example, actually represented an important success for tobacco interests. Without it, a much tougher FTC proposal would have taken effect, putting in place a stronger warning on packages and also on advertisements. Congress temporarily blocked a warning on advertisements, a requirement that the industry was eager to avoid. Preemption language in the bill also stripped states of the authority to impose tougher requirements on packages or advertisements. The legislation kept regulatory action centered in Congress, where tobacco interests were most powerful (DHHS 2000).

The industry also recognized—though it presented a contrary message to the public—that the mild warnings that Congress required in the 1965 and 1969 acts might prove helpful in suits by smokers who claimed that the companies had not informed them of the dangers of smoking. Indeed, in 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a case brought on behalf of a smoker, Rose Cipollone, that the 1969 act preempts state tort suits based on negligent failure to warn of the dangers of smoking, to the extent that such suits were based on a claim that the manufacturers’ and sellers’ post-1969 advertising ought to have included additional or more clearly stated warnings about the health consequences of cigarette smoking (Rabin 2001a). The trade-offs involved in the labeling legislation, as well as doubts about the impact of the product warnings, have led some public health experts to question whether the legislation was a public health victory (IOM 1994). Surgeon General Luther Terry, who issued the 1964 report, would later go so far as to call the 1965 law, “a hoax on the American people” (DHHS 2000).

The broadcast ban on tobacco advertising was probably also a net benefit to the industry. Between 1967 and 1970, when public health advocates aired counter advertisements as part of the Fairness Doctrine, cigarette

consumption dropped at a much faster rate than either before or after this period (DHHS 1989). Several studies have found that the ads were driving at least some of the downturn in smoking (Farrelly et al. 2003; Hamilton 1972; O’Keefe 1971; Warner 1989). When the congressional broadcast ban took effect (without much industry resistance), those advertisements disappeared from the nation’s living rooms, and the tobacco control movement lost one of its more effective tools for reducing tobacco use. Whatever the public health benefits of banning broadcast tobacco advertising, it was to the industry’s advantage to get the counter advertisements off the air.

After the television advertising ban, tobacco companies vastly increased their marketing budgets, shifting a large portion of advertising dollars into promotional activities aimed at (1) putting cigarettes in the hands of prospective users; (2) positioning cigarettes in prominent and accessible places at points of sale; and (3) creating good will for the companies with the public, community leaders, and politicians (IOM 1994). In 1975, the tobacco industry spent $491 million on all types of cigarette advertising and promotion in the United States. By 1985 that figure had nearly quintupled to $2.48 billon, and it continues to multiply (FTC 2005).

The industry prevailed in the courts as well. Of more than 200 tort claims filed on behalf of individual smokers between the mid-1950s and the early 1990s, not a single lawsuit succeeded. Tort litigation against the tobacco industry seemed to be dead. In a first wave of litigation, which began in the 1950s, the companies successfully argued that, absent a foreseeable risk of harm, consumers must bear the risks of using nondefective products. In the second wave, which began in the early 1980s, the industry successfully argued that smokers continued to smoke even with knowledge of the associated health risks (Rabin 1993).

The industry message that smoking was an individual choice—indeed, a right—and that others had no business depriving smokers of that pleasure resonated powerfully within American society. Even as antismoking forces were gathering steam and public knowledge of the dangers of smoking was high, smoking was widely seen as a personal decision, even if it was a self-destructive one. For those who were not smokers or tied to the tobacco industry, it could be a justification for steering clear of the controversy over smoking. As the remainder of this chapter reveals, however, new and increasing concerns about the health consequences of tobacco use would soon begin to reshape public opinion regarding smoking.

The Campaign Against Secondhand Smoke

Research about the harmful effects of secondhand smoke began to emerge in the 1970s. As nonsmokers sought to assert their right to a smoke-free environment, they introduced a new justification for tobacco control.

Eventually, this movement would weaken the claims of smokers’ rights and transform public perceptions and the tobacco policy debate. In the end, this shift also played a major role in reducing smoking altogether by changing social norms and helping smokers quit or reduce smoking.

Early research on secondhand smoke left many uncertainties about the nature and scope of the risk that tobacco smoke posed to nonsmokers, and specific scientific findings supporting nonsmokers’ rights claims did not emerge until the late 1980s. However, public health officials and grassroots antismoking groups—particularly the Group Against Smokers’ Pollution, or GASP, founded in 1971—did not wait. They embraced the early indications that smoking could harm nonsmokers, while locating their campaign for smoke-free environments in the context of a broader environmental protection movement along with a growing consumer health consciousness (Bayer and Colgrove 2002).

The 1972 Surgeon General’s report (HEW 1972) noted the potential hazards of secondhand smoke. By the mid-1970s, government at all levels and private companies were beginning to respond to calls for smoke-free areas. In 1973, domestic airlines were required to have a no-smoking section, and a year later smoking was restricted on interstate buses. Much of the action was taking place at the state and local levels. In 1973, Arizona became the first state to create smoke-free public places; in 1974, Connecticut became the first state with a law restricting smoking in restaurants; and in 1975, Minnesota became the first state to have a comprehensive workplace smoking ban (DHHS 2000).

The tobacco industry tried to focus attention on the lack of definitive data about the risks of secondhand smoke, but the threat to nonsmokers had caught the attention of the media and the public. By the late 1970s, a Roper poll commissioned by the Tobacco Institute found that almost 60 percent of respondents believed that smoking was probably harmful to nonsmokers, and even 40 percent of smokers agreed that their smoking probably endangered others (The Roper Organization Inc. 1978).

The campaign against secondhand smoke continued to gain momentum in the 1980s, with states and localities passing a variety of restrictions on smoking in public places. By 1986, 41 states and the District of Columbia had statutes restricting smoking (Bayer and Colgrove 2002). That year, reports from the National Academy of Sciences and the Surgeon General contributed to the sense of urgency about secondhand smoke. The report by the National Academy’s National Research Council stated that secondhand tobacco smoke increases the risk of lung cancer in nonsmokers by 30 percent and is harmful to children (NRC 1986). Surgeon General C. Everett Koop’s 1986 report (DHHS 1986), Health Consequences of Involuntary Smoking, acknowledged the limitations of the data but called for immediate measures to protect nonsmokers.

Congress banned smoking on all airline flights of 2 hours or less in 1987, and 3 years later effectively extended that prohibition to all domestic flights. Smoking was also banned in federal buildings and in child care facilities that received federal funds.

The 1992 release of the Environmental Protection Agency’s landmark report, Respiratory Health Effects of Passive Smoking: Lung Cancer and Other Disorders, added to the momentum for smoke-free spaces (EPA 1992). The report concluded that secondhand smoke is a Class A carcinogen, meaning that it is a definite cause of human cancer. According to the Environmental Protection Agency report, secondhand smoke causes some 3,000 deaths from lung cancer a year among nonsmokers.

Secondhand smoke gave new momentum to the efforts of tobacco control advocates, setting the stage for a fundamental shift in the political dynamic of tobacco control and in the public discourse and understanding of tobacco control efforts during the last decade of the 20th century.

ADVANCES IN TOBACCO CONTROL: 1988–2005

The tobacco control movement coalesced around the secondhand smoke issue, which turned out to be only the first of several issues to pose unprecedented challenges to commercial tobacco interests. While the science on the adverse effects of secondhand smoke continued to emerge, a second scientific front opened to counter the industry focus on freedom of choice: advances in neuroscience demonstrated that nicotine is a highly addictive drug. This finding permanently transformed the debate about smoking and reshaped the public policy agenda. The emphasis on addiction also cast smoking among adolescents and youth in a new light and stimulated a third front in the tobacco wars.

Nicotine: An Addictive Drug

Historically, the term addiction has been associated with stereotypical images of compulsive drug use, deviance, and criminality; heroin has been viewed as the prototypical addictive drug in the United States (HEW 1964). Beginning in the mid-1960s, however, scientific criteria for addiction (often labeled “drug dependence”) have emphasized the hallmark behavioral features of drug use, including a loss of control, and experts in the field have attempted to disassociate the clinical condition itself from the social and moral connotations and images traditionally linked with the term addiction. Equally important have been the major advances in neuroscience research that have identified the neurobiological substrates of addiction (IOM 1996) (see Chapter 2).

By the early 1980s, researchers reported that laboratory animals worked to acquire nicotine; this behavior is a hallmark of addiction to a substance.

Studies also demonstrated nicotine’s psychoactive effects, another component of addiction. Brain mechanisms for behavioral reinforcement and compulsive use were characterized (IOM 2001). Epidemiological studies showing that large majorities of smokers had tried and failed to quit added to the evidence of addiction.

The 1988 Surgeon General’s report (DHHS 1988), Health Consequences of Smoking: Nicotine Addiction, detailed how nicotine meets the criteria for an addictive drug, concluding that smokers smoke because they are addicted and that nicotine is the addictive agent. A growing number of scientific and medical organizations, including the World Health Organization, the American Medical Association, and the American Psychiatric Association, declared nicotine addictive or dependence producing.

The medical consensus that nicotine is an addictive drug transformed the concept of smoking from a bad habit of weak-willed people to a patho-physiological process that produces compulsive behavior. Increasingly, scientific studies have documented the pharmacological and structural effects of nicotine on the nervous system, which ultimately leads to specifiable changes in the brain.

The highly addictive nature of nicotine undermines the tobacco industry’s longstanding position that smoking is a “free choice” and, by drawing attention to the similarities between tobacco addiction and addiction to other psychoactive drugs, establishes the empirical and ethical foundation for more aggressive regulation. Although the FDA regulates nicotine patches and other nicotine-containing products used as aids for smoking cessation, FDA commissioners had traditionally declined to assert any jurisdiction over cigarettes. In the late 1980s, Scott Ballin, director of the Coalition on Smoking OR Health, petitioned the FDA to regulate low-tar cigarettes and the new smokeless brand Premier on the basis of their implied health claims that these products are less harmful than ordinary cigarettes (Kessler 2000). In response to the petition, FDA Commissioner David Kessler decided to explore a broader regulatory approach than one based on the “implied health claims” associated with low-tar cigarettes. In 1991, he created a team of FDA lawyers, scientists, and policy makers to study the policy implications of the finding that nicotine is an addictive drug. In particular, they explored whether the FDA could regulate nicotine under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (Kessler 2000).

The statutory definition of drugs under the FDA law refers to “articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body.” Kessler’s team would spend the next several years documenting both that nicotine affects the structure or function of the body and that the tobacco industry intends it to have that effect. The phrase “intended to” required evidence that nicotine was not merely an unavoidable component of tobacco but was also an ingredient that cigarette makers intended to

affect the structure or function of the body. Using internal industry documents that had become available in lawsuits and from industry insiders, FDA policy makers documented in the industry’s own words how tobacco companies manipulate nicotine levels and rely on the addictive qualities of nicotine to hook users (Kessler 2000).

Most Smokers Become Addicted as Adolescents

In the early 1990s, as the FDA tobacco team was exploring policy options, national experts on tobacco use had begun to highlight the importance of smoking among youth. Studies showed that nearly 90 percent of adult smokers began smoking by the time they were 18 years old and that every day some 3,000 young people began to smoke (DHHS 1994; IOM 1994; Pierce et al. 1989). In 1992, Congress passed the so-called Synar Amendment to limit youth access to tobacco by requiring states to control access as a condition of receiving federal substance abuse block grants (IOM 1994).

In 1994, two major reports highlighted the problem of smoking among youth: the Surgeon General issued Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People (DHHS 1994), and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released Growing Up Tobacco Free: Preventing Nicotine Addiction in Children and Youth (IOM 1994). Those reports described the problem of initiation of smoking and nicotine addiction among youth and the factors promoting use of tobacco use among young people. The IOM report recommended specific actions that could be used to address the problem, including proposals to curtail youth access to tobacco products, restrict youth-oriented tobacco marketing, limit advertising to a text-only format, narrow the preemption provision of the 1969 federal cigarette labeling law, and enact comprehensive federal regulation of tobacco products.

The recognition that most smokers become addicted in their teens further undermined the industry arguments against regulation based on free choice. Secondhand smoke findings demonstrated that smoking endangers nonsmokers, evidence of nicotine addiction established that the decision to continue smoking is not always a free choice, and now studies showed that the overwhelming majority of smokers are already on the path toward addiction before they turn 18 years of age (IOM 1994). The public may respond negatively to paternalistic, “Nanny State” policies aimed at changing the behavior of competent adults, but protecting children is a powerful justification for regulating dangerous products. Moreover, industry marketing in the 1990s (epitomized by R.J. Reynolds’ Joe Camel campaign) clearly had special appeal to children and teens and suggested that the industry was actually targeting young people, a suspicion subsequently borne out by internal industry documents.

The focus on youth and the revelations in industry documents caught on with the public. A 1993 Roper poll asked a sample of registered voters whether they mostly agreed or mostly disagreed with the following statement: “Even though tobacco companies say they don’t want kids to smoke, they really do everything they can to get teenagers and young people to take up smoking” (Marttila and Kiley Inc. 1993a). Of those polled, 64 percent said they mostly agreed, while 73 percent of the respondents reported an unfavorable or very unfavorable overall impression of the tobacco industry (Marttila and Kiley Inc. 1993b).

FDA Commissioner Kessler decided to focus the FDA regulatory approach on tobacco use among youth. Kessler, a pediatrician, called nicotine addiction a “pediatric disease” (Hilts 1995). On August 23, 1996, he joined President Bill Clinton in the White House Rose Garden to announce historic regulations that, for the first time, would put cigarettes under FDA control. The regulations declared cigarettes “nicotine-delivery devices” (DHHS 2000). Relying on the scientific foundation laid in the 1994 reports by the Surgeon General and the IOM, the new FDA regulations limited youth access to tobacco and controlled tobacco advertising and promotion targeted at young people. Immediately, tobacco companies challenged the regulations in federal court, initiating litigation that would eventually find its way to the U.S. Supreme Court (DHHS 2000).

States Take the Lead

In the early 1990s, while the FDA was exploring a federal role in regulating tobacco, states and localities had already begun to take action to contain the tobacco problem. Grassroots antitobacco advocacy was a driving force behind the creation of smoke-free spaces, and increasingly activists began to initiate other antismoking programs at the state and local levels. New antitobacco coalitions in the states began to effect important policy changes.

The burst of state action began in 1988, when the people of California passed Proposition 99, a referendum that increased the excise tax on tobacco from 10 to 35 cents per pack and earmarked 20 percent of the new revenues for a statewide antismoking campaign. California designed and put in place a comprehensive program that included mass media counter marketing campaigns, school-based programs, community-based interventions, and a research component. Massachusetts, Arizona, and a succession of other states followed with citizen referenda or legislation increasing tobacco excise taxes to various degrees and designating some of the money for antitobacco activities.

Historically, federal, state, and local governments have taxed cigarettes primarily to generate revenues, especially in response to budget crises. In

recent years, however, many states have viewed tobacco excise tax increases as a tool for reducing demand for tobacco while providing funding for public health measures (Rabin and Sugarman 2001). Many studies have found that the overall consumption of cigarettes declines with increases in the price of cigarettes (DHHS 2000) (see Chapter 5). Although figures on the “price elasticity” of demand for cigarettes vary somewhat, the general rule is that a 10 percent increase in the real price reduces overall consumption by about 4 percent and the rate of smoking among youth by 7 percent.

In addition to tax revenues, in the 1990s states received funds from philanthropic organizations and the federal government to create comprehensive tobacco control programs. The National Cancer Institute’s American Stop Smoking Intervention Study (ASSIST) demonstration program, a partnership with the American Cancer Society, funded 17 state health departments from 1991 to 1999. The program’s goal was to “alter states’ social, cultural, economic, and environmental factors that promote smoking” (NCI 2005). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Initiatives to Mobilize for the Prevention and Control of Tobacco program (IMPACT) funded tobacco control initiatives in the other states (except California).

Also in the early 1990s, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), under President Steven Schroeder, became the first philanthropy in the United States to make a major commitment to tobacco control. Over the next decade, the RWJF invested more than $400 million dollars in research, policy, and communications programs aimed at reducing the harm caused by tobacco (Bornemeier 2005). In 1994, RWJF created the SmokeLess States program, administered by the AMA, to support nongovernmental coalitions to educate the public and policy makers about the risks of tobacco use. The program was meant to augment the federal funding that was going to state governments and expand upon the innovations under way in California.

By the mid-1990s, every state had funds from one or more of these sources to build tobacco control programs. In 1999, the CDC replaced ASSIST and IMPACT with a nationwide program that provided funds to all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The Smokeless States program continued until 2004. Comprehensive state programs contained various initiatives, such as launching counter advertising and public education campaigns, establishing smoke-free workplaces and public spaces, increasing prices through taxation, supporting treatment programs for tobacco dependence, enforcing youth access restrictions, and monitoring performance and evaluating programs (IOM/NRC 2000). Some states, including California, Massachusetts, and Florida, pioneered innovative models that included edgy youth-oriented media campaigns that challenged youth not to let the tobacco industry manipulate them into smoking.

The state-based programs reflected a shift in tobacco control—from a reliance on efforts directed at individual behavioral change to community

approaches designed to change social and environmental influences on smoking behavior. Research suggested that this new emphasis would be beneficial, as studies had shown that interventions directed solely at individuals were not likely to result in large-scale declines in smoking prevalence (NCI 1991).

The tobacco industry recognized the potential of this new approach for reducing tobacco use and sought to defeat local initiatives and limit the scope and impact of the increasing activities of the states. The industry charged that advocacy activities amounted to illegal lobbying by public agencies (Aguinaga-Bialous and Glantz 1999; Gerlach and Larkin 2005). An evaluation of the ASSIST program, based in part on internal industry documents, found that the industry’s strategy was to burden the states with requests for documents under the federal Freedom of Information Act and accuse ASSIST staff and local coalition members with using funds for illegal lobbying, causing confusion over what actions the ASSIST program could legally take (NCI 2005). To stem the movement toward smoke-free spaces, the industry tried, often successfully, to convince state legislatures to enact lax statewide laws while precluding more stringent local ordinances (ANR 2004).

New Litigation Strategies

Commercial tobacco interests were also becoming increasingly engaged on another battleground. From the 1950s until the early 1990s, tobacco companies were consistently victorious against tobacco control efforts in the courts. Litigation had thus shown little promise as a tool for tobacco control (Rabin 1993). However, the findings about nicotine addiction, the revelations that companies had concealed and misrepresented health information, and new opportunities to aggregate cases in so-called class actions transformed the litigation landscape in the 1990s (Rabin 2001a).

Attorneys who had previously not been involved in tobacco litigation began suing tobacco companies on behalf of large groups of smokers (Rabin 2001b). The first tobacco class action was Broin v. Philip Morris, filed in 1991 on behalf of flight attendants who claimed that they were injured by secondhand smoke prior to the airline smoking ban. A $349 million settlement was reached before the trial concluded.

The nationwide class action suit Castano v. American Tobacco, filed in 1994, brought together some of the country’s leading plaintiff attorneys. Nicotine addiction was the centerpiece of the case, which drew on emerging evidence that companies tried to conceal and misrepresent the addictive properties of nicotine and that they knowingly addicted their customers. Although a federal appellate court eventually decertified the class in the Castano case, subsequent individual tort suits and class actions suits

continued to develop the addiction argument. Some suits were successful, although not all rulings were upheld on appeal. Other pending cases accuse tobacco companies of fraud over use of words like “light” and “low-tar” to imply that cigarettes with these characteristics are less hazardous to a person’s health. Potentially the most significant case of this kind, Schwab v. Philip Morris, was certified as a class action in a federal district court in New York in 2006. The “third wave” of tobacco litigation, beginning in 1994, has been summarized by Douglas et al. (2006) and Janofsky (2005). In what proved to be a pivotal legal milestone in the history of tobacco control, in 1994 Mississippi Attorney General Michael Moore filed a suit against the tobacco companies to recover the state’s Medicaid expenditures on residents with tobacco-related illnesses. Because the state was the injured party under Moore’s legal theory, he bypassed the industry’s customary defense in suits filed by smokers that the smokers were responsible for their own injuries (Fisher 2001). Soon every state filed similar suits.

Moore and several other state attorneys general negotiated a so-called global settlement with the major tobacco companies in 1997. The proposed agreement would have bound the industry to various tobacco control efforts, including restrictions on advertising and promotion, and would have accepted FDA jurisdiction over cigarettes. The agreement would also have settled all pending state suits and would have immunized the companies from all class action litigation. According to Stanford law professor (and committee member) Robert Rabin: “Beyond doubt, [the agreement] was a testament to the awesome threat posed by the [states’] litigation strategy” (Rabin 2001b).

Congressional approval was required for the agreement to be binding. Legislation sponsored by Senator John McCain to implement the settlement and put in place other measures favored by tobacco control advocates became a target for aggressive lobbying by both those for and those against the bill. The legislation divided the tobacco control advocates, with some leaders—including David Kessler and former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop—opposing it on the ground that it was too favorable to the tobacco companies. The proposed legislation was caught up in a filibuster and never received a floor vote (Pertschuk 2001).

However, a short time later—on November 23, 1998—the attorneys general of 46 states, the District of Columbia (and American territories such as Guam and Puerto Rico) signed the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) with the major tobacco companies (National Association of Attorneys General 1998).

The MSA required companies to pay an estimated $206 billion to the 46 states between 2000 and 2025. (Four states—Florida, Minnesota, Mississippi, and Texas—had previously reached a settlement that obligated the

companies to pay those states more than $40 billion.) Because the MSA did not envision FDA jurisdiction or other federal action, it did not require congressional approval; the required approval came from state legislatures and the courts.

The MSA also required the companies to support a new charitable foundation—which came to be the American Legacy Foundation—to reduce teenage smoking and substance abuse and to prevent tobacco-related diseases. The MSA placed numerous restrictions on industry marketing and promotion, including the elimination of cartoon characters and billboard advertising and restrictions on tobacco company sponsorships of various events. The MSA also constrained the industry’s political activity, disbanding the Tobacco Institute and the Council for Tobacco Research, and included a number of other provisions (National Association of Attorneys General 1998).

In return for these concessions, the tobacco companies that signed the agreement received protection from lawsuits by state Medicaid programs. The agreement also contained provisions to protect manufacturers from new competitors by providing for reductions in their required payments if the participating companies lost market share to other companies as a result of the agreement.

The MSA did not prohibit suits by or on behalf of smokers or by the federal government. In 1999, the Clinton Administration filed a landmark lawsuit against the major cigarette companies under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) and the Bush Administration continued to prosecute the litigation. On the basis of the evidence introduced at the trial, which began in 2004 in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, the federal government argued that the companies “engaged in and executed—and continue to engage in and execute—a massive 50-year scheme to defraud the public, including consumers of cigarettes, in violation of RICO,” and that the companies’ “past and ongoing conduct indicates a reasonable likelihood of future violations.” Although the government originally sought “disgorgement of Defendants’ ill-gotten gains,” the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled out disgorgement and limited the scope of the remedy to “forward-looking” actions designed to prevent continued RICO violations. District Judge Gladys Kessler subsequently found that the defendants were liable under RICO and imposed a remedial order aimed at preventing future violations including bans on the use of misleading terms such as “light” and requiring corrective statements in a variety of channels to overcome the defendants’ past efforts to deny the addictive character and adverse health effects of smoking. (For further discussion of the RICO remedy, see Chapter 6.)

Momentum Builds

Major advances in tobacco control occurred both in the courts and in legislatures during a short period of time, thereby reversing the political momentum that long seemed to favor the tobacco industry in Congress and state legislatures. Thus, by end of the 1990s, tobacco control advocates were energized and optimistic about further gains in the 50-year effort to end the tobacco problem. At about this time, the architects of Healthy People 2010 (DHHS 2002) set an ambitious goal of reducing the prevalence of smoking among adults (defined as smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetimes and who now report smoking cigarettes every day or on some days) in half—from the 1998 baseline of 24 percent, to 12 percent in 2010. For high school students the target was a 54 percent drop from the 1999 smoking prevalence rate of 35 percent to a rate of 16 percent in 2010 (smokers in high school were defined as those having smoked one or more cigarettes in the previous 30 days).

Despite setbacks and persistent opposition, important milestones in tobacco control were attained in the 1990s and early 2000s. The MSA and the four-state settlement placed some controls on the industry and provided for large payments to the states. The American Legacy Foundation, established and funded pursuant to the MSA, sponsored a nationwide counter advertising campaign, the first in 30 years. The campaign, modeled on the “truth” campaign in Florida, was linked to 22 percent of the decline in the rate of smoking among youth between 1999 and 2002. The overall rate of smoking among students in grades 8, 10, and 12 dropped from 25.3 percent to 18 percent during that period. This translates into approximately 300,000 fewer young smokers (Farrelly et al. 2005) (see Chapter 5 and Slater, Appendix N).

Studies have also linked comprehensive tobacco control activities to decreases in smoking among youth. A recent study of state expenditures on tobacco control found, “clear evidence that tobacco control funding is inversely related to the percentage of youth who smoke and the average number of cigarettes smoked by young smokers” (DHHS 1994; Tauras et al. 2005). The smoking rates in states with the most aggressive programs declined more than the national average. Recently, in Maine, for example, the rates of smoking declined 59 percent among middle schools students and 48 percent among high school students between 1997, when the state began its campaign, and 2003 (Tobacco Free Kids 2004).

Aggressive state antismoking campaigns also contributed to the overall decrease in the prevalence of smoking among adults beginning in the late 1990s. Early evidence of the impact of these programs came from the California Tobacco Control Program, which was associated with nearly twice the rate of decline in smoking prevalence as that in the rest of the United

States between 1989 and 1993 (Gilpin et al. 2001). The National Cancer Policy Board (a joint program of the IOM and the National Research Council) examined the evidence on the effectiveness of state programs and concluded in a 2000 report that, “multi-faceted state tobacco control programs are effective in reducing tobacco use” (IOM/NRC 2000). The evidence on the effects of the state programs is reviewed in Chapter 5.

A growing number of states, localities, and workplaces have become smoke-free. Nine states—California, Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington—have comprehensive, statewide smoke-free laws (ALA 2005, 2006). The laws in Florida, Idaho, and Utah exempt only stand-alone bars. Studies and economic data show that fears that restaurants and bars would suffer economically from smoking bans have not generally been borne out. Some of the strongest evidence of the impact of secondhand smoke policies comes from New York City, where a comprehensive smoking ban took effect on March 30, 2003. In the year after the law took effect, business receipts for restaurants and bars increased, the rate of employment rose, and the number of liquor licenses increased. Virtually all establishments are complying with the law, which has the support of most New Yorkers (Tobacco Free Kids 2006). According to a 2005 report, 18.4 percent of adults in New York City smoke, a decline from 19.2 percent a year earlier and a decline from 21.6 percent from 2 years earlier. These declines are significantly steeper than those for the nation overall (Perez-Pena 2005).

A substantial increase in cigarette prices has also occurred over the past decade. The federal excise taxes on cigarettes rose from 24 cents to 39 cents per pack between 1993 and 2002, many states raised their cigarette taxes, and the major manufacturers increased prices by about a dollar per pack, including 45 cents a pack to cover the cost of the MSA (Capehart 2001). In 1997, premium brands cost about $1.90 per pack, and by 2003 the cost had increased to about $3.60 a pack, with higher prices in states with higher taxes (Derthick 2004).

The exposure of the tobacco companies’ deceptive marketing practices not only resulted in widespread criticism of the industry but also created a new justification for legal action and regulation. A dramatic measure of how much had changed was the new corporate stance of the country’s largest cigarette company, Philip Morris USA. In the fall of 1999, Philip Morris acknowledged in a public statement that smoking causes cancer and that nicotine is addictive (Meier 1999). A few months later, Philip Morris officially took the position that cigarettes should be regulated (AP 2000). Only a few years earlier, the company’s chief executive officer (who had since left the company), along with the chief executive officers of other major tobacco companies, testified before a congressional committee (under oath) that he did not believe that nicotine is addictive (Waxman 1994).

More effective smoking cessation techniques that use pharmacological and behavioral methods recently became available, although many smokers still lack access to quitting services. The federal government released clinical practice guidelines to provide health care professionals with the latest information available on effective treatment strategies to help smokers quit. A subcommittee of the federal government’s Interagency Committee on Smoking and Health developed a National Action Plan for Tobacco Cessation aimed at preventing 3 million premature deaths and helping 5 million smokers quit. In February 2004, the day before the plan was released at a news conference, Secretary of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson announced the establishment of the National Quitline Network with an allocation of $25 million per year. The subcommittee estimated to reach its goals; however, the cost of the quit line would be $3.2 billion a year. Ten months later, Thompson announced the toll-free number for this quit line (1-800-QUITNOW). In early 2005, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced that smoking cessation counseling would become a covered Medicare benefit, the second of the subcommittee’s six recommendations to be addressed (Michael Fiore, personal communication, June 30, 2005).

One important objective of many tobacco control advocates has not been realized, however. In 2000, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act does not give the FDA the authority to regulate tobacco (FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. [98-1152] 529 U.S. 120, 2000). This left in place the incongruous situation in which the FDA and other agencies have authority over products that cause far less harm than cigarettes while cigarettes continue to evade meaningful federal regulation.

After the Supreme Court’s decision, attention turned to Congress. In 2004, a Senate bill giving the FDA the authority to regulate tobacco was attached to a $10 billion buyout of tobacco growers. Although the bill passed by a large margin in the Senate, the provisions related to the FDA were eliminated in conference committee. Comprehensive and bipartisan bills were reintroduced in 2007. Like its predecessors, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (S.625 and HR 1008) would give the FDA wide-ranging authority over the manufacture, distribution, and promotion of tobacco products (Legal Resource Center for Tobacco Regulation 2005).

Among other important provisions, S.625 and HR 1008 would revive the 1996 FDA Tobacco Rule, strengthen cigarette package warnings and authorize the FDA to prescribe stronger warnings in the future, and give the FDA the authority to require cigarettes to meet health-based performance standards. The bill has widespread support among tobacco control advocates as well as the endorsement of Philip Morris USA. Notwithstanding the

broad powers that it would give the FDA, some tobacco control advocates oppose it because it would legitimize tobacco products and might deter the development and marketing of reduced-risk products.

Since the 1980s, tobacco companies have experimented with novel tobacco- and cigarette-like products designed to reduce the toxicity of smoking and the level of secondhand smoke emissions. These products have taken various forms over the years, including cigarette-like devices that heat rather than burn tobacco and, more recently, cigarettes with reduced carcinogen emissions. Harm reduction products, also referred to as PREPs (potential reduced-exposure products), are potentially beneficial, but there is not yet enough scientific evidence to determine their effectiveness in reducing harm from smoking (IOM 2001).

Companies have test marketed PREPs in recent years, but few have been introduced and few are marketed nationally. In 2005, Vermont, joined by several other states, sued the R.J. Reynolds company over the company’s claims that its Eclipse cigarette, which heats tobacco without actually burning it, might reduce the risk of cancer and other health problems (AP 2005).

Although congressional action on tobacco had been stalled since 2004 until recently, important litigation victories have continued to occur. In 2006, U.S. District Judge Gladys Kessler ruled in favor of the federal government in its massive RICO case against the tobacco companies alleging that they had engaged in misleading conduct for decades as part of a broad conspiracy (United States v. Philip Morris USA Inc., et al., 99-CV-2496, 2006). As noted above, Judge Kessler’s remedial order was limited to actions designed to prevent future violations of RICO because earlier rulings had precluded “backward-looking” remedies such as disgorgement of the profits made by the defendant cigarette manufacturers:

[T]he Court is enjoining Defendants from further use of deceptive brand descriptors which implicitly or explicitly convey to the smoker and potential smoker that they are less hazardous to health than full flavor cigarettes, including the popular descriptors “low tar,” “light,” “ultra light,” “mild,” and “natural.” The Court is also ordering Defendants to issue corrective statements in major newspapers, on the three leading television networks, on cigarette “onserts,” and in retail displays, regarding: (1) the adverse health effects of smoking; (2) the addictiveness of smoking and nicotine; (3) the lack of any significant health benefit from smoking “low tar,” “light,” “ultra light,” “mild,” and “natural” cigarettes; (4) Defendants’ manipulation of cigarette design and composition to ensure optimum nicotine delivery; and (5) the adverse health effects of exposure to secondhand smoke.

Judge Kessler’s RICO rulings regarding liability and remedy are now on appeal. In addition, findings similar to those made by Judge Kessler have

provided the factual foundation for substantial punitive damages awards in states courts. Although some of these awards have been reduced on appeal on the grounds that they were unconstitutionally excessive, the courts have rarely questioned the factual basis for the findings or the suitability of some award for punitive damages for the industry’s “reprehensible conduct” (see generally, Guardino and Daynard 2005).

TOBACCO CONTROL IN THE YEARS AHEAD: WILL PROGRESS CONTINUE?

Has Momentum Slowed?

The public health community has made significant progress over the past decade, but there are also worrisome signs that progress may be stalling. It is difficult to sustain public attention on an endemic health problem over an extended period. Other pressing public health concerns, such as obesity and disparities in the provision of health care, have increasingly commanded the attention of both public and private leaders in the health care sector. Budgetary constraints in federal agencies, such as NIH and the CDC have affected tobacco control research. Moreover, in recent years many states have chosen to cut tobacco control funding and to divert MSA payments to needs other than tobacco control (GAO 2006).

Billions of dollars are flowing to the states from the MSA and the accompanying four-state settlement. By the end of 2003, the 46 MSA states had received more than $46 billion. Each state determines how much of that money will be allocated for tobacco control activities, however, and with states experiencing serious budget shortfalls in the early years of the new millenium, many chose to divert substantial portions of those funds to help balance budgets and meet other state needs. Additionally, some states used the stream of money to secure bonds, forfeiting future MSA funds to get money immediately. Even when the states were not experiencing such a deep financial crisis, less than 5 percent of MSA funds to the states were being spent on tobacco control (Gross et al. 2002; Schroeder 2002).

The CDC has recommended minimum levels that states need to spend to achieve successful tobacco prevention and cessation (CDC 1999). As of December 2004, only three states—Delaware, Maine, and Mississippi—met that minimum. The District of Columbia and 37 states fund tobacco control programs at less than half the CDC minimum or provide no funds at all. Some of the states with the most innovative programs, including Minnesota, Florida, and Massachusetts, have substantially reduced their tobacco control budgets. 2005 marked the third straight year that states overall cut their tobacco control expenditures (Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids 2004).

When support for tobacco control wanes, earlier progress in reducing tobacco use can quickly be reversed by the social forces that tend to promote smoking. Industry expenditures on traditional advertising have declined in the wake of the marketing restrictions imposed by the MSA. However, promotional activities remain very strong, as the companies concentrate on direct contact with potential consumers and retail promotions, particularly price discounts. As a result of a heavy emphasis on price promotions, tobacco companies spent a record $15.15 billion on cigarette advertising and promotion in the United States in 2003 (the year for which latest data are available), which represents an increase of 21.5 percent over that in 2002, 35.0 percent over that in 2001, and 58 percent over that in 2000. The amount for the 2003 is more than twice what companies were spending just 5 years earlier (FTC 2005). As marketing to underage smokers has been curtailed, companies have increasingly targeted the 18- to 21-year-old market (Tobacco Free Kids 2005).

Tobacco companies are spending $28 on marketing tobacco products for every dollar that the states spend on tobacco prevention efforts, according to a report by a coalition of public health agencies. Stated in another way, tobacco companies spend more money on marketing in a single day than 46 states and the District of Columbia spend on preventing smoking in a year (Tobacco Free Kids 2004).

The market share of nonparticipating discount cigarettes marketers has increased since the agreement was signed, even though MSA provisions were designed to avoid such an increase. As a result, most funding for the American Legacy Foundation ended after 5 years because continued funding was conditioned on maintenance of at least a 99.05 percent market share among the four companies that signed the agreement (American Legacy Foundation 2003).

Many smokers still lack access to effective cessation services; and physicians do not routinely address tobacco use with patients, despite the dissemination of national clinical guidelines. Several recommendations of the Interagency Committee on Smoking and Health, including investing in research into new tobacco dependence interventions, have not been addressed. Current treatments result in long-term success at quitting among only 10 to 30 percent of smokers (Fiore et al. 2004).

The Consequences of Unchanged or Weakened Tobacco Policies and Programs

In sum, over the last decade considerable progress in building a strong foundation for continued efforts to reduce tobacco use has been made, but the momentum appears to have slowed. Indeed, there are genuine reasons for concern that the infrastructure for tobacco control is eroding while the

tobacco industry’s efforts to promote and maintain demand are continuing to increase. It is these concerns that led the American Legacy Foundation to ask the IOM to evaluate strategies that can be used to continue to reduce tobacco use and to examine barriers to the implementation of those strategies. As a part of this undertaking, the committee believed that it was necessary to consider the likely consequences not only of intensified tobacco control activities but also of standing still or even a weakened investment in tobacco control efforts. Thus the committee decided to explore the available tools for projecting trends in tobacco use under different sets of assumptions. Scientists who do this type of work create mathematical models of the “system” of tobacco use, quantifying the factors that affect the outcomes of interest, such as the prevalence of use, tobacco-related mortality, and health expenditures.

No one can ever be certain what will happen in the future, and predictions in this domain are complicated by the fact that the system of tobacco use is complex in the technical, as well as the everyday, sense of the word. However, certain aspects of future patterns of use, morbidity, and mortality are relatively predictable because they display considerable inertia and lagged behavior. For example, even if, starting today, not one additional person were to begin smoking, the prevalence of tobacco use would still decline relatively slowly over time. Likewise, even if, starting today, every current smoker were to decide to quit and were able to do so permanently, there would still be substantial smoking-related morbidity and premature mortality for many years to come.

The committee’s charge requires it to estimate the consequences of adopting or not adopting particular tobacco control policies and programs on future patterns of use. Making that sort of projection is inevitably somewhat speculative. Careful use of certain technical tools can lead to better-informed projections than mere human intuition can produce, however, particularly for systems with lags and inertia. Accordingly, the committee surveyed the macrolevel tobacco policy simulation literature thoroughly and commissioned analyses based on two macro- or population-level tobacco simulation models: the SimSmoke model (Levy, Appendix J) and the System Dynamic Model (Mendez, Appendix K). Although the committee is confident that these two models represent the state of the art in the domain of tobacco policy, it is important to emphasize that this body of knowledge is rather incomplete compared with the enormous knowledge base concerning the individual-level consequences of smoking and past and current patterns of smoking. The models may also appear to be incomplete compared with the completeness of the policy simulation tools available in other policy domains. (Particular limitations of the state of the art in tobacco policy modeling are outlined in Chapter 7.) The limitations of the

models must be taken into account in deciding how much weight should be given to projections based on them.

Both of the models used in the committee’s analyses are what might be called “compartmental” or “stocks-and-flows” models. They track over time the number of people in various “states,” such as the number of female smokers in the past year between the ages of 25 and 34 years. Levels of these “stocks” change over time because of “flows” in and out because of smoking initiation, cessation, and relapse and underlying demographic changes (aging, death, etc.). For the present purposes, the most important difference between these two models concerns what each takes as inputs. The System Dynamic Model projects the consequences of particular initiation and cessation rates. It answers questions of the form, “Suppose that the rate of smoking initiation fell by 10 percent. What would that imply for smoking prevalence in 15 years?” The SimSmoke model backs up one step and uses policies as inputs. The SimSmoke model’s policy modules translate evidence pertaining to historical policy actions into estimated effects on flow rates, which then, in turn, affect smoking prevalence over time.

The modeling commissioned by the committee is focused on smoking prevalence because the committee believes that prevalence can be projected more reliably than smoking-related morbidity and mortality. (As indicated above, however, that does not mean that model-based projections of future rates of smoking prevalence are necessarily accurate; the accuracy of these projections is limited by the inevitable uncertainty of the future and by the limitations of the models or the data used by the modelers.)

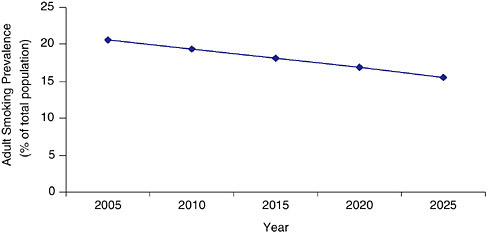

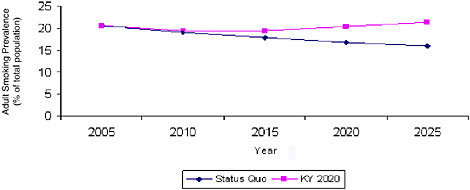

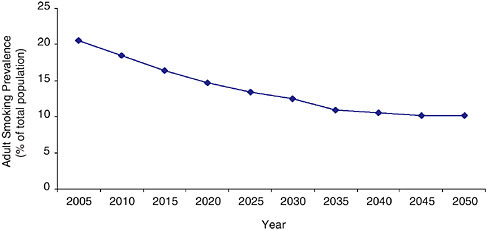

Projections Based on the Status Quo

The first question of interest to the committee in carrying out its charge is what trends can be expected in tobacco use prevalence if the level and intensity of tobacco control remain unchanged. Figures 3-1 and 3-2 give those projections by use of the SimSmoke model and System Dynamic Model, respectively. Specifically, the SimSmoke model projects what would happen if the tobacco control policies of 2005 were maintained with no additions or retrenchments. The System Dynamic Model shows what might occur if the smoking initiation and cessation rates of 2005 were maintained in the future. The models reveal that there is good news and bad news for public health with regard to reducing tobacco use in the future.

The good news is that both models show that, even if tobacco control activities remain at present levels, smoking prevalence will decline from 2006’s estimated 20.9 percent to a little less than 16 percent in 2025. This continued decline will occur because of the system’s inertia: there are currently more middle-aged and older smokers than there would have been

FIGURE 3-1 Estimated adult smoking prevalence from the SimSmoke Model (2005 to 2025) assuming no change in the tobacco control environment (status quo scenario).

had those birth cohorts passed through the ages of tobacco initiation under higher tobacco prices and stronger tobacco controls. Over time, as those birth cohorts are replaced by aging younger cohorts who had lower rates of smoking initiation, the prevalence of smoking will continue to decline.

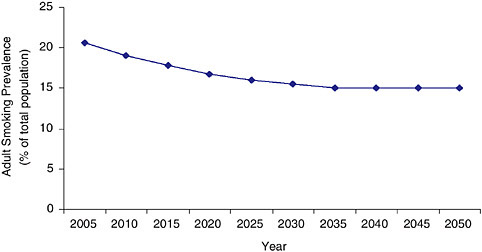

The System Dynamic Model projects further into the future than SimSmoke, in this case, until the year 2050; and this projection gives the

FIGURE 3-2 Estimated adult smoking prevalence from the System Dynamic Model(% of total population) (2005 to 2050) assuming no change in the tobacco control environment (status quo scenario).

bad news. One must keep in mind that the further into the future that one projects, the greater the uncertainty of the projection is; however, the System Dynamic Model shows that shortly after 2025, the decline in prevalence will plateau well above the Healthy People 2010 target of 12 percent, halting at about 15 percent.

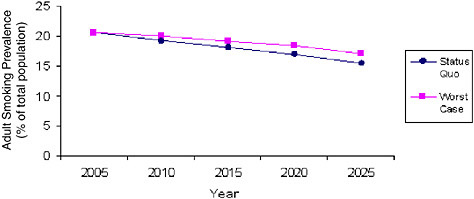

Projections Based on Weakened Tobacco Control

Both of these two, independent models give similar projections under base-case conditions, but future conditions could look quite different. As noted above, the risk of backsliding in tobacco control is considerable. With this in mind, the SimSmoke model was used to project a worst-case scenario based on a weakening of tobacco control policies and programs. Table 3-1 (Table 4 from Levy, Appendix J) shows the SimSmoke model projections of the consequences of various adverse changes in the baseline assumptions about the intensity of various tobacco control policies and programs. Specifically, the envisioned changes are reductions in tobacco prices of 40 and 80 cents per pack (whether these are due to reduced production costs, tax cuts, or price reductions in the face of competition from discount brands and Internet sales); the elimination of enforcement and publicity for clean air laws (but leaving the laws in place), elimination of media campaigns aimed at adults and youth, such as the American Legacy Foundation and Massachusetts state campaigns; elimination of quit lines; and, finally, the effects of all these changes together.

Any of these actions alone would increase the smoking prevalence in 2025 relative to the baseline or status quo projection of 15.5 percent prevalence. If all of these retrenchments occurred, the projected smoking prevalence in 2025 would be 17.1 percent, which would result in approximately 4 million more people smoking than would otherwise be the case (see also

TABLE 3-1 SimSmoke Model Prediction of Trends in Adult Smoking Prevalence (2005 to 2025) Assuming a Decline in Selected Tobacco Control Measures

|

Measure |

Smoking Prevalence (%) |

||||

|

2005 |

2010 |

2015 |

2020 |

2025 |

|

|

40-cent-per-pack price reduction |

20.6 |

19.6 |

18.6 |

17.6 |

16.3 |

|

80-cent-per-pack price reduction |

20.6 |

19.9 |

18.9 |

18.0 |

16.7 |

|

Clean air law reduction |

20.6 |

19.3 |

18.1 |

17.0 |

15.6 |

|

Adult media campaign reduction |

20.6 |

19.4 |

18.2 |

17.0 |

15.7 |

|

Youth media campaign reduction |

20.6 |

19.3 |

18.3 |

17.2 |

15.8 |

|

Cessation program reduction |

20.6 |

19.3 |

18.1 |

17.0 |

15.6 |

|

All |

20.6 |

20.0 |

19.2 |

18.4 |

17.1 |

Figure 3-3). Although the momentum generated by the last four decades of tobacco control is unlikely to be erased altogether, these projections do show that a weakened commitment to tobacco control will affect millions of lives; and the model does not take into account new smoking fads, other changes in demand, or industry innovations.

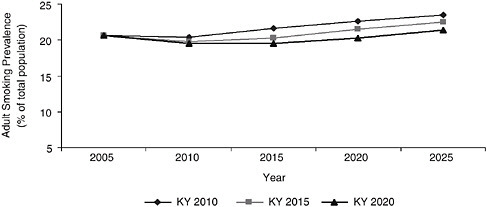

In Chapter 1, the committee observed that the patterns and trends of tobacco use differ substantially in different regions and states and that these differences arise to some extent from differences in the nature and the intensity of tobacco control activities. To depict the range of possible outcomes, the System Dynamic Model was used to project what would happen to smoking prevalence if, over the next 4 years (by 2010), the entire country’s smoking initiation rates rose and smoking cessation rates fell to match those prevailing in Kentucky, the state with highest smoking prevalence, in 2005. If this were to occur, national smoking prevalence could rise—and could rise substantially, to 23.5 percent by 2025, an increase of approximately 11 million smokers. It is unlikely that tobacco control initiatives throughout the country would lose ground so quickly, but this calculation graphically makes the point that the inertial continuation of past trends should not be taken for granted. The committee also used the System Dynamic Model to estimate the changes in smoking prevalence that would occur if the country were to reach Kentucky’s 2005 smoking initiation and smoking cessation levels in 2015 and 2020, scenarios that are more realistic. As shown in Figure 3-4, the results were equally disturbing: even imagining that it would take 15 years for smoking initiation and smoking cessation rates to reach Kentucky’s levels, the model predicts that there would be more than 17 million more smokers by 2025 than under the status quo scenario displayed in Figure 3-5.

FIGURE 3-3 Comparison of SimSmoke Model estimates of adult smoking prevalence (2005 to 2025) under the status quo and worst-case scenarios.

FIGURE 3-4 System Dynamic Model estimated adult smoking prevalence assuming the U.S. matched the 2004 initiation and cessation rates of Kentucky by 2010, 2015, and 2020.

Conversely, the committee wondered what would happen to overall national tobacco use prevalence if, over the next few years, tobacco control efforts intensified to the point that the entire country had initiation and cessation rates by 2010 that matched those of California in 2004. California was selected for this purpose because it is, to some extent, a model state with respect to both tobacco control policies and tobacco use. The projected trajectory is parallel to the national projection, but it plateaus at substantially lower levels, eventually reaching the 10 percent target of Healthy People 2010—albeit in 2050, almost two generations later than the 2010 milestone (Figure 3-6). Accordingly, there would appear to be substantial room for advances in tobacco control efforts to make a positive

FIGURE 3-5 System Dynamic Model estimated adult smoking prevalence comparing Kentucky 2020 scenario with the status quo scenario.

FIGURE 3-6 System Dynamic Model estimated adult smoking prevalence assuming the U.S. reaches California’s 2004 initiation and cessation rates by 2010.

difference. The effects of intensified tobacco control activities are explored in Chapter 5.

SUMMARY

This chapter has documented the progress in building a strong foundation for state tobacco control activities that has been made over the last decade. However, there are genuine reasons for concern that the infrastructure for tobacco control is eroding while the tobacco industry’s efforts to promote and maintain demand are continuing to increase.