6

Changing the Regulatory Landscape

The first prong of the committee’s blueprint for reducing tobacco use, set forth in Chapter 5, envisions strengthening traditional tobacco control measures. If the plan set forth in Chapter 5 is successfully implemented and sustained, it could have a significant impact on tobacco use; but even an optimistic projection leaves prevalence at 10 percent in 2025, and a more realistic projection might be 15 percent. The main argument presented in this chapter is that a more substantial long-term impact requires a change in the current legal framework of tobacco control to a new, innovative regulatory approach that takes into account the unique history and characteristics of tobacco.

Over the past two decades, tobacco control policy has developed incrementally as the nation has moved step-by-step from a laissez-faire legal system embedded in a smoking culture to a system with coherent antismoking policy grounded in public health. Incremental reforms, however, will not end the nation’s tobacco problem. A more fundamental shift must occur. It is time for Congress and other policy makers to change the legal structure of tobacco policy, thereby laying the foundation for a strategic initiative to end the nation’s tobacco problem, that is, reducing tobacco use to a level that is insignificant from a public health standpoint. In this chapter, the committee sets forth the blueprint for a new regulatory approach.

Currently (and under the interventions of the blueprint outlined in Chapter 5), the implicit model of tobacco control is demand reduction combined with reactive efforts to prevent the tobacco industry from impeding demand-reducing policies. This leaves in place the supply side (the product and its existing channels of distribution) as well as all the existing

incentives for attracting more consumers and selling more cigarettes. A more ambitious strategy would ask these questions: Can anything be done to substantially curtail the availability of tobacco products? Can anything be done to change tobacco products to make them less hazardous? Is it possible to bring the industry’s incentives into closer alignment with the public health goals of tobacco control? No existing regulatory statute provides a model for tobacco products because there is no other lawful product for which the declared public goal is to suppress its use altogether. A new legal regime, new models, and new policy paradigms are needed.

The challenge, then, is to craft a policy framework that is aligned with the unique aim of tobacco control policy: to substantially reduce, if not eliminate, the use of this unusually damaging product without replicating the problems associated with the prohibition of alcohol in the 1920s and with the contemporary prohibitions of illegal drugs (e.g., widespread noncompliance, violent black markets, corruption, and high rates of arrest). In this chapter and Chapter 7, the committee offers several ideas for more fundamental change.

FEDERAL REGULATORY AUTHORITY IS NEEDED

It is clear that the U.S. Congress has the constitutional authority to enact national legislation bearing on all domains of tobacco control, including banning the distribution and use of tobacco products, analogous to the authority that it exercises over controlled substances such as peyote and marijuana. The pertinent policy questions are (1) whether Congress should exercise its constitutional authority (by prescribing national rules or by delegating the authority to do so to a federal agency, such as the Food and Drug Administration [FDA]), or, conversely, whether it should allow the states to exercise primary authority to regulate the production, distribution, marketing, and use of tobacco; and (2) if Congress does exercise federal regulatory authority in any of these domains, whether it should leave any room for supplemental state regulation and, if so, within what constraints. The committee believes that the time has come for Congress to exercise its acknowledged authority to regulate the production, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products while freeing the states to supplement federal action with their own measures that aim to suppress tobacco use and that are compatible with federal law.

Relationship Between Federal and State Tobacco Regulation

Setting aside the complexities of a complicated body of federal law, Congress has essentially three options: (1) state control, in which the federal government leaves regulation in a particular domain to the states (and,

depending on state law, to localities); (2) federal preemption, in which the federal government has complete regulatory control and precludes any state regulation in the area; and (3) complementary regulation, in which the federal government establishes regulations on a particular subject but does not exclude the states from also establishing regulations. Under the third approach, the federal action typically establishes minimum requirements for the whole country (the basic requirements) while allowing the states to adopt more stringent regulations. Familiar examples of these three approaches include the state regulation of the retail distribution of alcohol, federal preemption of the state regulation of employee benefit plans under the Employee Retirement and Income Security Act, and complementary regulation of controlled substances.

At present, tobacco regulation in the United States is characterized by plenary state control except in the federally preempted domain of information or warnings “based on smoking and health,” as defined in the 1969 Cigarette Labeling Act. The preemption language adopted by the Congress has been construed broadly by the U.S. Supreme Court to preempt “failure to warn” product liability suits under state tort law and direct state or local regulation of tobacco advertising, as well as the obviously preempted area of mandated warnings on packages or in advertisements (Cipollone v. Liggett Group I1992;505 U.S. 504; Lorillard Tobacco Company v. Reilly 2001;533 U.S. 525).

Whether federal regulation is needed and, if so, whether and to what extent the federal regulatory statute should preempt compatible state regulation are complex inquiries involving highly contextual judgments. However, the general contours of the analysis can be summarized succinctly. On the one hand, a decision to preempt state regulation in favor of exclusive federal authority may impose an overly rigid and inefficient uniform nationwide approach that is contrary to public preferences in many jurisdictions, especially when the benefits and costs from regulation vary considerably across jurisdictions. For example, a state with no tobacco farmers to protect may want to impose stricter regulations than a tobacco-growing state, or a state with a large Hispanic population might want to insist on labels in both English and Spanish. As another example, because the prevalence of smoking varies by as much as threefold among the states, the voters in a state with more smokers may find public smoking regulations more oppressive than the voters in another state with fewer smokers.

Nationwide rules can be especially inefficient when it comes to regulatory matters that fall almost exclusively within a state’s geographic boundaries. Thus the regulation of smoking in public places is primarily a local matter, with individual business establishments and local governments bearing the brunt of the compliance costs. The same might also be said for restrictions on point-of-sale advertising, including the in-store placement of

placards and the proximity of external store window signs to schoolyards. Consider in this respect a hypothetical national ban on certain activity (such as the sale of alcohol) within a certain radius of a school. What seems like a perfectly reasonable distance, say, 1,000 yards, would have a very different impact on lawful access to alcohol in a dense urban area, where the ban might cover an entire city, than it would in a less densely populated suburban or rural area. Finally, the imposition of a nationwide approach can increase the costs of a regulatory error, especially when there is uncertainty over the most appropriate form of regulation and when the scientific evidence and business environment are changing.

As these observations suggest, there are many reasons why regulation of retail distribution, marketing, and use of tobacco should presumptively be left to state regulation and, to the extent that federal regulation is adopted in these domains, that supplementary state regulation should be permitted as long as it is compatible with the federal regulatory objectives.

However, in some contexts, there are strong arguments for a national regulatory approach, and perhaps for national uniformity. One such context is the regulation of commercial products for which there is a national market and where the regulated products are easily transported across state lines. For example, if there are substantial differences in regulatory standards from one state to another, strong incentives would exist for people to purchase less heavily regulated products in one state and sell them in a state with more demanding regulatory requirements, thereby potentially undermining the latter state’s regulatory objectives, creating a black market, and possibly attracting the participation of criminal syndicates. Another concern that sometimes arises in situations involving diverse state regulation of product characteristics is inefficiency attributable to the need for manufacturers to comply with 50 different requirements. A third consideration is the need for continuing oversight and research by experts, as is often the case in environmental protection.

Regulation of pharmaceutical products, where national standards have prevailed since adoption of the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906, is pertinent illustration of a strong national regulatory interest, potentially high costs to state-by-state variations, and need for ongoing regulatory oversight. Over time, the Congress has tended to both increase the scope of federal regulatory authority and precluded additional state regulation in areas in which the FDA has acted. Explicit statutory preemption has been adopted in connection with FDA regulation of medical devices, over-the-counter drugs, and cosmetics.

As will be explained below, the committee favors strong regulation of tobacco product characteristics, packaging, labeling, and promotion and distribution. The colossal failure of the tobacco market to produce accurate information regarding the health effects of tobacco products and

to produce adequate incentives for companies to develop less hazardous products, the national scope of the problem, and the need for creating and sustaining regulatory expertise argue strongly for national regulation. The residual question is whether supplemental, compatible state regulation should be permitted. In the committee’s view, a uniform national approach preempting state regulation altogether makes the most sense in relation to regulations governing tobacco product design and labeling, as well as in relation to marketing through national media. A uniform national approach makes the least sense in relation to the retail distribution, local marketing, and consumption of tobacco. Federal regulation may not be needed in some of these areas at all, but even if federal regulations are adopted, the federal rules should set the floor, and supplemental state regulation should be permitted. In this latter respect, the current federal preemption provision unduly constrains the prerogatives of the states in regulating the local marketing of tobacco products.

Recommendation 23: Congress should repeal the existing statute preempting state tobacco regulation of advertising and promotion “based on smoking and health” and should enact a new provision that precludes all direct state regulation only in relation to tobacco product characteristics and packaging while allowing complementary state regulation in all other domains of tobacco regulation, including marketing and distribution. Under this approach, federal regulation sets a floor while allowing states to be more restrictive.

This approach was embodied in the proposed “Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act” (S. 625 and HR 1008), introduced on February 15, 2007, by Senators Kennedy and Cornyn with 29 other Senators and Congressmen Waxman, Davis, and Palone. This will be referred to as the proposed Tobacco Control legislation in this report.

Any federal statute preempting direct state regulation of the product and its packaging should not preempt any private or public causes of action, in state or federal courts, based on a failure to warn consumers about any risks (of which the company was aware) not covered by the federally prescribed warnings or based on claims of fraud or conspiracy. Congress should make its intentions regarding the narrow scope of preemption clear in the legislative record.

EMPOWERING FDA TO REGULATE TOBACCO

In 1994, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Growing Up Tobacco Free urged Congress to adopt a regulatory framework for tobacco products and to empower a federal regulatory agency to implement it:

Congress should confer upon an administrative agency the authority to regulate the design and constituents of tobacco products whenever it determines that such regulation would reduce the prevalence of dependence or disease associated with use of the product or would otherwise promote the public health. The agency should be specifically authorized to prescribe ceilings on the yields of tar, nicotine, or any other harmful constituent of a tobacco product (IOM 1994, p. 246-247).

Soon after the IOM report was released, the FDA surprised many observers by claiming that Congress had already given the agency the authority to regulate cigarettes as nicotine delivery devices under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and by issuing a rule regulating the marketing and distribution of cigarettes to youth. Eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the FDA’s position, ruling that the FDCA did not authorize the FDA to regulate tobacco products and striking down the 1996 FDA Tobacco Rule (FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 529 U.S. 120, 2000).

Since the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision, proposals have been pending in the Congress to authorize the FDA to regulate tobacco products. The version pending at the time of the final version of the committee’s report is the proposed Tobacco Control legislation, which would give the FDA wide-ranging authority over the manufacture, distribution, and promotion of tobacco products with a few exceptions, which will be described below. The power granted to FDA in the proposed Tobacco Control legislation is even more extensive than that envisioned in Chapter 8 of Growing Up Tobacco Free (IOM 1994).

Under the proposed Tobacco Control legislation:

-

The 1996 FDA Tobacco Rule relating to youth access and marketing to youth would be revived.

-

FDA would have broad authority to promulgate tobacco product standards whenever such a standard is found to be “appropriate for protection of the public health,” taking into consideration “the risks and benefits to the population as a whole, including users and non-users of tobacco products.” (The bill embodies the principles relating to products purporting to reduce exposure to toxins and to reduce disease risk developed by the IOM in Clearing the Smoke [2001].)

-

Legally required package warnings would be strengthened immediately and FDA would have the authority to revise these requirements upon finding “that such a change would promote greater public understanding of the risks associated with tobacco.”

-

FDA would have authority to “restrict … the sale and distribution of a tobacco product if the Secretary [of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services] determines that such regulation would be appropriate for the protection of the public health.”

-

FDA would be empowered to restrict the advertising and promotion of tobacco products “to the full extent permitted by the First Amendment” upon finding “that such regulation would be appropriate for the protection of the public health.”

Each of these topics is discussed below. Overall, however, the committee reiterates the view taken by two previous IOM committees (IOM 1994, 2001): broad federal regulatory authority over the manufacture, distribution, marketing, and use of tobacco products is an essential element of a comprehensive public health approach to tobacco control.1 Congress does not have the institutional capacity to monitor and respond to ongoing innovations in product design (especially those purporting to reduce exposure to tobacco-related toxins), or to changes in marketing or patterns of consumption, whereas FDA personnel are well-positioned to gather the necessary information and to make evidence-based scientific judgments about the likely public health consequences of alternative regulatory approaches. Overall, the potential benefits of agency regulation in this context seem to far outweigh its potential costs. Specifically, the committee does not agree with the view expressed by some tobacco control advocates that empowering FDA to regulate the manufacture, distribution, promotion, and use of tobacco products necessarily “legitimizes” these products or that it will unavoidably lead to the “regulatory capture” of the agency by the tobacco industry. Other objections to the federal regulation and to particular features of the proposed Tobacco Control legislation are discussed below in the specific contexts in which they arise.

Recommendation 24: Congress should confer upon the FDA broad regulatory authority over the manufacture, distribution, marketing, and use of tobacco products.

A REGULATORY PHILOSOPHY

The ultimate regulatory goal is to reduce smoking-related mortality and morbidity to a level that is acceptable to a well-informed American public.

Under the present circumstances, given what is known about the health consequences of tobacco use, reducing the prevalence of smoking and the level of per-capita cigarette consumption are reasonable proxies for reducing harm. In the context of other health and safety regulations, the goal of reducing cigarette consumption to a socially acceptable level might mean reducing it to the lowest feasible level or the level at which the social costs of trying to reduce it further exceed the public health benefits of doing so. Either way, feasibility is a significant constraint on the regulatory measures that can sensibly be adopted. Most importantly, a total prohibition against tobacco manufacture and distribution is not a realistic option at present or for the foreseeable future.

The United States now has 44.5 million adult smokers (CDC 2005), the vast majority of whom are addicted to the nicotine in cigarette smoke. If it were possible to prevent smoking initiation altogether, it might be feasible to embrace a nicotine maintenance approach, under which tobacco products would be lawfully available only by prescription to people who are addicted to nicotine. However, the experience with marijuana and other illegal drugs demonstrates that prohibition does not eliminate initiation even when there is no lawful market for a psychoactive drug, and it is implausible to expect that tobacco products lawfully available to more than 40 million addicts would not spill over into a large “gray” market that would sustain ongoing initiation, especially by young people. Nor is it plausible that the billions of cigarettes produced for the international market would not find their way into the United States.2

The challenge, then, is to frame a policy for tobacco production and distribution within the context of a regulated market. What should be the aims of the regulatory agency over the short term? In the committee’s view, the following aims should guide tobacco policy for the foreseeable future:

-

Undertake significant and sustained efforts to reduce the rate of initiation of smoking

-

Maximize the options available to addicted smokers to help them quit or reduce their risk

-

Prevent people from becoming addicted to tobacco products if they use them

-

Reduce the risks of using tobacco products to the users and to others

|

2 |

Although prohibition accompanied by prescription-only cigarettes for already addicted smokers might reduce smoking initiation, the committee anticipates that the costs of enforcing such an approach would be substantial and would exceed the potential public health gains. However, such an approach may be worthy of consideration at some future time, especially if it is combined with the nicotine reduction concept sketched in Chapter 7. Innovative strategies of this kind should be explored by the tobacco policy research office recommended in that chapter. |

Policies designed to achieve these aims must be formulated and implemented on the basis of a careful consideration of their potential effectiveness and potential costs. A key factor is the need to avoid creating a substantial black market and its associated costs.

The remainder of this chapter sets forth several elements of the comprehensive regulatory strategy that should supplement the traditional tobacco control approaches described in Chapter 5. Specifically:

-

Tobacco product characteristics should be regulated to protect the public health.

-

Messages on tobacco packages should promote health.

-

The retail environment for tobacco sales should be transformed to promote the public health.

-

New models for regulating the retail market should be explored.

-

The federal government should mandate industry payments for tobacco control and should support and coordinate state funding.

-

Tobacco advertising should be further restricted.

-

Targeting of youth by tobacco manufacturers for any purpose should be banned.

-

Youth exposure to smoking in movies and other media should be reduced.

-

Surveillance and evaluation should be enhanced.

TOBACCO PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS SHOULD BE REGULATED

As noted above, the proposed Tobacco Control legislation would grant FDA the authority to regulate tobacco products. FDA was selected because it is the only existing regulatory agency with expertise both in scientific and health issues and in product regulation. The authority that would be conferred on FDA for tobacco regulation in the proposed Tobacco Control Legislation parallels in many ways current FDA authority for the regulation of drugs, although different regulatory criteria are needed. Requiring tobacco products to be “safe” is not an available option, of course, and prohibition of the existing products is not a feasible regulatory strategy. Overall, the regulatory standard should be to “protect the public health” by reducing initiation, promoting cessation, preventing relapse, reducing consumption, and reducing product hazards. This standard incorporates its own limitation because it will require the agency to evaluate the likely consumer responses to any proposed regulation, including the likelihood of product substitution and the creation of black markets that could nullify the anticipated public health benefits of the regulation.

FDA regulates many consumer products, including drugs and foods, and the agency has many tools at its disposal that can be deployed in tobacco regulation. FDA regulation serves to inform consumers about the constituents of the products that they consume and to enhance the safety of these products. FDA can require existing and new products to meet toxicant exposure standards and can promote new standards and make products less hazardous. FDA can also ensure that the claims made about products are truthful and are not misleading. If FDA is authorized to regulate tobacco products, the task should be undertaken in the context of a comprehensive framework that includes the regulation of novel tobacco products and other nicotine delivery products, the delivery of tobacco smoke constituents, and the regulation of medications used to treat tobacco addiction.

The need for a tobacco regulatory authority is illustrated by the history of the low yield cigarette, which has been described in detail in a recent IOM report and in National Cancer Institute (NCI) Monograph 13 (IOM 2001; NCI 2001). In brief, low-yield cigarettes were developed after scientific evidence indicated that cigarette tar contributed to cancer. Low-tar cigarettes were implicitly promoted by the tobacco industry as a way to reduce the health risks of smoking. A large majority of smokers believe that low-yield cigarettes were less harmful, and many have switched to low-yield cigarettes rather than quit smoking (Kozlowski et al. 1998). However, because of the engineering characteristics of the cigarettes and the tendency of the smokers to maintain their desired levels of nicotine in their bodies, smokers easily compensate for low-yield cigarettes by smoking more intensively and by smoking more cigarettes (NCI 2001). One strategy used to decrease cigarette tar delivery was to change tobacco blends. However the tobacco contained higher levels of nitrogenous chemicals that resulted in the generation of larger amounts of NNK, a tobacco-derived substance that is known to be a pulmonary carcinogen. The ultimate result of the shift to low-yield cigarettes was no reduction of toxic exposures and no impact on smoking-related disease risks. Unfortunately, however, low yield cigarettes were promoted for more than 30 years before it was publicly understood that they have no beneficial effect on smoking-related risk (NCI 2001).

Evidence introduced in the U.S. Department of Justice Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organization (RICO) suit against the tobacco manufacturers indicated that for many years company scientists and company officials had internal information indicating that “light” cigarettes might not deliver lower doses of toxicants and that such cigarettes delivered lower dosages to machines than they did to human smokers (NCI 2001). Moreover, tobacco company researchers had information that the tar from a “light” cigarette might be qualitatively more toxic on a milligram-per-milligram basis than the tar from a regular filtered cigarette. However, public health professionals and officials in other government agencies failed to appreciate

the seriousness of the problem for several reasons. First, lacking the information possessed by tobacco manufacturers, they mistakenly assumed that smoking machines could accurately gauge the relative toxicity of cigarettes. They underestimated the complexity of the cigarette product and the ability of manufacturers to change the product in ways not reflected in the machine-based measurements. Second, lacking complete information about smoker compensation possessed by tobacco manufacturers, they underestimated the behavioral inclination of smokers to maintain their desired levels of nicotine intake. As a result of industry deception, there was a massive regulatory failure, as nothing was done to control how these products were marketed.

The best way to prevent such a sequence of events from occurring again is to have a regulatory body that can systematically assess toxic exposures, make judgments about potential risks from tobacco products, regulate industry claims about the products to ensure that they are accurate and not misleading, set minimum standards, and provide relevant surveillance to determine actual human exposures and risks. This is particularly important because a number of tobacco companies are developing and marketing tobacco products that are intended to reduce the harm from smoking and presumably will be promoted as such.

Goals of Tobacco Product Regulation

The regulation of tobacco product characteristics can be seen as having two primary goals (IOM 2001). One is to reduce the harm from the continued use of tobacco products. This might be achieved by reducing the toxic emissions from cigarettes or the toxic constituents of smokeless tobacco. Reducing toxic exposures would potentially lower the risk and severity of disease in people who continue to smoke. It is essential, however, that the federal government assure that consumers are informed about what is and what is not known about the risks of using products that result in reduced toxic exposures (reduced exposure products). Moreover, regulators must take steps to reduce the likelihood that the availability of reduced-exposure products will increase initiation or reduce the number of users who quit. The danger that the marketing of reduced-exposure products could lead to an increase in smoking prevalence by altering risk perceptions about smoking is one of the greatest challenges that the FDA will need to address.

The second goal of regulating tobacco product characteristics is to reduce consumption. The most promising way of reducing consumption through product regulation would be to make cigarettes less addictive, thereby making quitting easier and preventing initiating smokers from becoming addicted. Another promising strategy is the development of new medications for the treatment of nicotine addiction. To the extent that harm

reduction policies are pursued, it would be desirable to bring modified tobacco products and medications for smoking cessation within a common regulatory framework.

Reducing Harm from Continued Use

The regulation of tobacco products could potentially reduce the harm of tobacco use in smokers who continue to use these products. The approaches to and the pitfalls associated with harm reduction have been reviewed extensively in a recent IOM report (IOM 2001). Some of the ways in which the harm of tobacco products might be reduced include (1) setting performance standards to reduce toxic emissions from cigarettes, (2) evaluating novel and potential reduced exposure products (PREPs), (3) educating users about the risks and benefits of novel products, and (4) encouraging the development of medication that can substantially reduce cigarette consumption (for example, maintaining abstinence through the use of medications). In addition, a national regulatory program would conduct ongoing surveillance of the use of novel and traditional tobacco products.

Making Tobacco Products Less Addictive

The manufacture of cigarettes allows for the control of the nicotine content of the tobacco. Nicotine can be extracted from tobacco and then added back to tobacco to achieve any desired level of nicotine. Although nicotine-free cigarettes were marketed in the past, they were not commercially successful.

For people addicted to controlled substances or alcohol, a common approach to reducing their drug use and minimizing withdrawal symptoms is to gradually taper the use of an addictive drug over time. Such gradual tapering allows a gradual reduction of the dose, a decrease in the level of tolerance, and minimization of the severity of withdrawal symptoms. This type of treatment has been used to treat heroin addicts by gradually increasing the doses of methadone that they receive and to treat alcohol and sedative drug addicts by using drugs such as phenobarbital and benzodiazepines.

An analogous approach could be the basis for a regulatory strategy to reduce the addictiveness of cigarettes (Benowitz and Henningfield 1994; Henningfield et al. 1998). The idea would be to reduce the nicotine content of cigarette tobacco gradually over time. This would result in a lowering of the level of nicotine intake and, presumably, a lowering of the level of nicotine dependence. As nicotine levels become very low, cigarettes would become much less addicting. As a consequence, fewer novice smokers would become regular lifelong smokers. For previously addicted smokers,

a reduction of nicotine dependence would be expected to facilitate quitting. This approach is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

Another proposed approach to making tobacco products less addictive includes removing flavorants and additives that enhance the sensory characteristics of cigarettes, as sensory characteristics are thought to contribute to the reinforcing qualities and the addictiveness of cigarettes.

Increasing Medicinal Nicotine Alternatives

Another way to deal with potential compensation would be to make medicinal nicotine more readily available. Currently, nicotine-containing medications are available both over the counter and by prescription, but they tend to be more expensive than cigarettes and are more difficult to obtain. With the ready availability of nicotine-containing medications, smokers could obtain supplemental nicotine to compensate for reduced nicotine intake from low-nicotine–content cigarettes (Henningfield et al. 1998). After complete smoking cessation, the nicotine dose in the medication could be tapered down over time to finally eliminate all dependence on the drug.

The Proposed Tobacco Control Legislation Provisions for FDA Product Regulation

The proposed Tobacco Control legislation would give the FDA authority to “restrict the sale and distribution of a tobacco product if the Secretary determines that such regulation would be appropriate for the protection of the public health.” This broad authority is limited only in the following ways: the FDA (1) may not prohibit the sale of tobacco products altogether, (2) may not require a prescription for tobacco products, (3) may not adopt a minimum purchase age higher than 18 years, and (4) may not ban any particular category of retail outlet from selling tobacco products. As general principles guiding FDA authority, decisions would be based on sound science; the goals would be both to reduce consumption and to reduce the mortality and morbidity caused by tobacco use, and the FDA efforts are expected to complement (and not replace) proven prevention and cessation efforts. The proposed Tobacco Control legislation provisions for FDA product regulation has the key elements described in the following sections.

Disclosure

The bill would require tobacco companies to disclose to the FDA all chemical compounds found in both their tobacco products and the products’ smoke, whether these compounds are added or occur naturally, by quantity. Tobacco companies would be required to disclose the content

and form a delivery based on standards established by the FDA, to disclose research on their product as well as behavioral aspects of its use, and to notify the FDA whenever there is a change in a product.

Testing

The bill would grant the FDA the authority to promulgate regulations on cigarette testing methods, including how the cigarettes are tested and which smoke constituents must be measured. The FDA would also determine what product test data are disclosed to the public to inform consumers, without misleading them, about the risks of tobacco-related disease.

Product Standards

The FDA would be given broad authority to promulgate tobacco product standards whenever such a standard is found to be “appropriate for protection of the public health,” taking into consideration the risks and benefits to the population as a whole, including users and nonusers of tobacco products. The FDA is specifically directed to take into account the increased or decreased likelihood that existing users of tobacco products would stop using such products and the increased or decreased likelihood that those that do not use tobacco products would start using such products. As indicated earlier, the proposed Tobacco Control legislation reflects a statutory formulation of the principles developed by the IOM in Clearing the Smoke. The FDA is specifically authorized to promulgate standards requiring “reduction of nicotine yields of the product” as long as it does not require that nicotine be reduced “to zero.” (The bill stipulates that only an act of Congress can require that nicotine yields be reduced to zero.) The agency is also empowered to promulgate standards “for reduction or elimination of other constituents, including smoke constituents or harmful components of the product.” In short, the FDA is empowered to embrace a harm reduction approach by reducing the toxicity of tobacco products.

Potential Reduced-Exposure Products

The bill would authorize the FDA to develop specific standards for evaluating novel products that companies intend to promote as reducedexposure or reduced-risk products. Such products would be those, as indicated by the manufacturer explicitly or implicitly, that present a lower risk of tobacco-related diseases or that are less harmful than other commercially-marketed tobacco products; tobacco products or their smoke that contain a reduced level of a substance or whose use results in a reduced exposure to a substance; or tobacco products that, when smoked, do not contain or are

free of a particular substance. The FDA would be granted the authority to regulate reduced-exposure and reduced-risk health claims and to ensure that there is a scientific basis for the claims that are permitted.

Public Health Concerns Regarding Federal Tobacco Product Regulation

Proposed FDA regulation has received mixed support from the public health community and from the tobacco industry. Some public health groups, such as the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, have worked with members of Congress in developing the proposed legislation and have been highly supportive of its content. Other public health groups have also endorsed the proposal (Tobacco Free Kids 2007a, 2007b). However, some tobacco control advocates have opposed the bill (AAPHP 2007). They have done so on two quite different grounds. Some opposed the product regulation features of the bill because adoption of a regulatory approach will, in some sense, legitimize a product that should be banned outright. For these opponents, the goal is prohibition, and the most likely political path to prohibition is state-by-state action. Others have argued that the proposed regulatory framework for PREPs, based on the recommendations in Clearing the Smoke, is too demanding and may impede the development of reduced-exposure products by stifling innovation and retarding competition with safer products, especially by small companies and new entrants into the market. For these opponents, the goal is harm reduction, and the federal government should be giving companies incentives to develop PREPs rather than putting regulatory obstacles in their paths.

A third line of objection to federal tobacco product regulation arises out of a deep-seated skepticism about the ultimate utility of federal tobacco regulation. Tobacco control advocates are mindful of the tobacco industry’s past successes in using federal legislation to obstruct tobacco control efforts, and their concerns are reinforced by general skepticism about the natural history of regulation. Under this view, regulatory agencies rarely have as much information as the regulated companies and therefore are prone to regulatory mistakes. Eventually, regulatory agencies tend to be captured by the industry that they are regulating, performance standards tend to be set by the industry itself, and consumers are often worse off than they would have been without regulation.

For some of the critics who hold this perspective, the main problem with the tobacco industry is not under-regulation, but, rather, oligopolistic concentration, which tends to encourage collusion and suppress competition. These critics believe that the industry has engaged in collusive activity throughout the century—even since the political and legal tide turned against it—and there is no reason to think that this will change. As long as this is true, the argument continues, there is a need to be realistic about

the poor prognosis for getting positive results through federal regulation. Rather, ways should be found to break up the industry. From this perspective, competition, not regulation, is the answer.

Committee Response to Public Health Concerns

The committee has given careful consideration to the concerns raised by some public health advocates about the proposed Tobacco Control legislation’s product regulation features. In the end, we think the fears are overstated and that federal tobacco product regulation is an essential element of a long-term strategy for achieving substantial reductions in tobacco use and in tobacco-related morbidity and mortality. One of the major reasons for this conclusion is that active federal monitoring and regulation of the tobacco market is needed to prevent, curtail, and counteract industry efforts to undermine tobacco control policies. A second reason is that the market for reduced-risk products is likely to replicate the “light” cigarette experience in the absence of aggressive regulation of claims about these products.

Reducing use and reducing harm Although harm reduction might be a useful adjunct to a comprehensive tobacco control strategy, it is not at the center of the committee’s charge, which is to propose a blueprint for reducing tobacco use in the United States. Reduced-exposure cigarette products may not reduce the prevalence of tobacco use and may have little public health payoff in the short term; moreover, given the numerous uncertainties identified in Clearing the Smoke, even an optimist would have to be reserved about the long-term payoff. A recent simulation study by Tengs and colleagues reinforces the cautious perspective enunciated in Clearing the Smoke (Tengs et al. 2004). They conclude that even if the new products do reduce harm to smokers by as much as 20 percent, the long-term consequences are highly likely to be negative if the rate of cessation drops by 20 to 40 percent.

Whatever the long-term prospects for harm reduction as a tobacco control strategy, however, industry efforts to develop and market reduced-risk or reduced-exposure products must not be left unattended, because their promotion and use could interfere with efforts to reduce tobacco use. This was the sad lesson of so-called “light” cigarettes. From this standpoint, it is imperative that Congress empower the FDA to regulate the claims that may be made regarding PREPs. In this respect, the FDA’s regulatory jurisdiction over PREPs is an essential component of the blueprint.

Risks and Benefits of Regulation

The general arguments against product regulation enunciated by opponents of the proposed Tobacco Control legislation strike the committee as

overstated in the specific context of tobacco regulation. First, the committee believes that the FDA, a public health agency, is unlikely to become allied with, much less captured by, the tobacco industry. Admittedly, the tobacco industry’s successful efforts to fend off regulatory action in the 1970s and 1980s give one pause. For example, the NCI’s harm reduction program (the Tobacco Working Group [TWG]), which operated from 1968 to 1977, failed because many of its key members were scientists with direct ties to tobacco manufacturers. The NCI did not assemble a working group of independent scientists in great part because there was insufficient expertise in cigarette design and evaluation outside the industry. As documents produced in litigation have revealed, industry scientists, notwithstanding their pronouncements that they were participating solely as individuals rather than as company representatives, repeatedly informed their companies’ legal counsel of any contemplated action by the TWG that might threaten the industry’s interests. Company scientists, acting on instructions from counsel, successfully blocked promising research projects that had been proposed to the TWG. Once the TWG was disbanded, the tobacco companies retained two of its government representatives as consultants. In particular, the director of NCI’s program, Gio Gori, went on to represent the Brown and Williamson Corporation in various regulatory proceedings.

Likewise, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has been criticized for its failure to stand up to the tobacco manufacturers. As documents produced in litigation reveal, the FTC passively allowed the industry to obscure the fact that the machine-tested tar and nicotine testing bore little relationship to human exposure. The FTC had no independent knowledge of cigarette design, and the FTC did not regulate the amounts of tar and nicotine delivered. However, its perpetuation of the testing regime merely served as an instrument for disciplining firms that threatened the industry-wide agreement to stick to machine-measured tar and nicotine numbers and avoid any suggestion that the machines did not accurately gauge human exposure. Moreover, the fact that the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) had to include a variety of restrictions on misleading and youth-oriented advertising provides evidence of regulatory default by the FTC. Finally, the fact that Judge Gladys Kessler, in her final judgment and order in the government’s RICO suit, enjoined the major tobacco manufacturers from using such words as “low tar,” “light,” “ultra-light,” “mild,” and “natural” provides even further evidence that the FTC has failed to carry out its legislative mandate (Tobacco Free Kids 2006).

The committee acknowledges the regrettable history of federal regulatory default. However, the committee believes that the widespread condemnation of the tobacco industry’s deceit during the 1970s and 1980s, most recently documented in Judge Kessler’s opinion in the federal government’s RICO suit, makes it less likely that any federal regulatory agency, especially

an agency charged with protecting the public health such as the FDA, will be captured by the tobacco industry. There is no doubt that the agency could still be misled, but the proposed Tobacco Control legislation’s disclosure requirements are designed to reduce the informational disparity between the industry and the regulators, and the FDA scientists can be expected to be highly skeptical of the data and the interpretations of those data provided by the tobacco industry.

Aside from regulatory capture, the other major criticism of the proposed Tobacco Control legislation is that the agency might retard innovation in the development of PREPs by insisting on high standards of proof regarding the effects of reduced exposure to tobacco toxins. In the committee’s view, however, even if the regulatory criteria for permitting reduced-exposure and reduced-risk claims might be applied too cautiously, the dangers of unregulated competition over safety are greater than the dangers of retarding safety innovation. The underlying question regarding harm reduction is whether it is better to err in one direction or the other. In the committee’s view, the highest priority is to prevent another “light” cigarette disaster.

The committee concludes that product regulation by the FDA will advance tobacco control efforts in the United States and around the world. The proposed Tobacco Control legislation embodies the principles that should govern the regulation of tobacco products in the coming years. The disclosure and testing requirements are needed to correct massive information failures in the tobacco market. The IOM’s approach to reduced-exposure products, which is embodied in the bill, strikes the right balance between encouraging innovation and protecting the public from misleading claims. Empowering FDA to reduce the nicotine content of tobacco products has great potential (see Chapter 7).

Recommendation 25: Congress should empower FDA to regulate the design and characteristics of tobacco products to promote the public health. Specific authority should be conferred

-

to require tobacco manufacturers to disclose to the agency all chemical compounds found in both product and the product’s smoke, whether added or occurring naturally, by quantity; to disclose to the public the amount of nicotine in the product and the amount delivered to the consumer based on standards established by the agency; to disclose to the pubic research on their product, as well as behavioral aspects of its use; and to notify the agency whenever there is a change in a product;

-

to prescribe cigarette testing methods, including how the cigarettes are tested and which smoke constituents must be measured;

-

to promulgate tobacco product standards, including reduction of

-

nicotine yields and reduction or elimination of other constituents, wherever such a standard is found to be appropriate for protection of the public health, taking into consideration the risks and benefits to the population as a whole, including users and non-users of tobacco products; and

-

to develop specific standards for evaluating novel products that companies intend to promote as reduced-exposure or reduced-risk products, and to regulate reduced-exposure and reduced-risk health claims, assuring that there is a scientific basis for claims that are permitted.

These recommendations are generally compatible with Articles 9-11 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO 2003).

MESSAGES ON TOBACCO PACKAGES SHOULD PROMOTE HEALTH

The tobacco industry has long used cigarette packaging to identify and market its products, and governments have long used cigarette packaging to convey messages about tobacco risk and exposure. As legal restrictions have increasingly reduced or eliminated media advertising, the importance of the package as a vehicle for promotion has increased (Slade 1997). The packages carried by smokers serve as mobile advertisements for particular products. Promotional displays of packages in retail outlets are also key marketing tools. In response to the increasing importance of the package in promotion, governments have begun to exert more control over packaging characteristics for the dual purposes of reducing this form of marketing and communicating directly with consumers.

Among the reasons for regulatory interest in tobacco packaging are

-

communicating product information to consumers and potential consumers,

-

warning consumers about hazards and thereby discouraging consumption,

-

communicating other health information (e.g., cessation hotline numbers),

-

preventing smuggling (by requiring documentation of excise tax payment),

-

preventing misleading messages by tobacco companies and providing corrective information to counteract previous deceptions,

-

preventing promotional messages by tobacco companies as other avenues of advertising are curtailed, and

-

“denormalizing” tobacco products.

The use of packages to convey tobacco-related health risks has a number of potential advantages over other forms of communication. The frequency of exposure is high. The messages are delivered at the moment a smoker desires another cigarette. The messages on packages also communicate information to the public at large, and not merely the consumer.

Package Warnings Regarding Tobacco-Related Health Risks

Congress first required health warnings on cigarette packages in 1966 and in advertisements in 1972. By 1985, four rotating warnings were required on both packages and in advertisements. However, U.S. package warnings are still not prominent and are located on the side of the package in small print (see Figure 6-1). In 1994, a previous IOM committee made the following observation about this country’s tobacco health warnings:

The adequacy of the current cigarette warnings has been repeatedly questioned by public health specialists. Moreover, in the committee’s view federal cigarette labeling legislation has reflected an unsatisfactory compromise between the public’s health and the tobacco industry’s desire to avoid concurrent state regulation and to reduce its exposure to tort liability. Negotiations in the legislative process have tended to favor the industry…. The inadequacy of current labeling policy is clearly revealed in the declaration of congressional purpose in the Comprehensive Smoking Education Act of 1984: It is the purpose of this Act to provide a

FIGURE 6-1 An example of U.S. government’s warning on cigarette packages.

new strategy of making Americans more aware of any adverse health effects of smoking, to assure the timely and widespread dissemination of research findings, and to enable individuals to make informed decisions about smoking. It is time to state unequivocally that the primary objective of tobacco regulation is not to promote informed choice but rather to discourage consumption of tobacco products, especially by children and youths, as a means of reducing tobacco-related death and disease. Even though tobacco products are legally available to adults, the paramount public health aim is to reduce the number of people who use and become addicted to these products, through a focus on children and youths. The warnings must be designed to promote this objective. In the committee’s view, the current warnings are inadequate even when measured against an informed choice standard, but they are woefully deficient when evaluated in terms of proper public health criteria” (IOM 1994, p. 236-237).

This committee agrees. Although federal law has remained unchanged for more than 20 years, evidence regarding the ineffectiveness of the prescribed warnings has continued to accumulate. As Krugman and colleagues note, the U.S. package warnings have served the tobacco industry well by reducing their liability exposure while communicating ineffectively with smokers and potential smokers (Krugman et al. 1999). The basic problems with the U.S. warnings are that they are unnoticed and stale, and they fail to convey relevant information in an effective way. In contrast to the messages used in other countries, the United States requires one of four text messages in black and white that occupy only 50 percent of the side of a pack. These messages have not changed in 20 years. They therefore have little effect on decision making or behavior (see Ferrence, Appendix C).

In contrast to the experience with such warnings in the United States, the experiences with these warnings in Canada and other countries have been more promising.

The Canadian Experience

Voluntary health package warnings were introduced in Canada in 1972 but were first imposed by federal law in 1989. Initially, they included four text messages. Five years later, eight stronger messages were introduced, and these messages occupied the top 35 percent of the front and back panels of the pack. These messages clearly specified the diseases and conditions caused by smoking and confirmed that “cigarettes are addictive.” These messages were soon adopted in Australia, Thailand, and Poland.

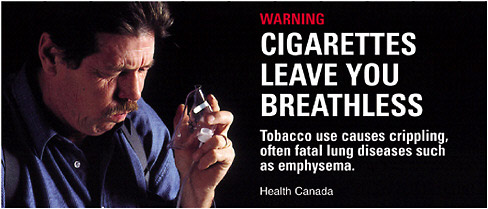

The most important innovation in package regulation is requiring companies to print graphic messages with pictorial content. Graphic warnings were first introduced in Canada in 2001. The manufacturers of cigarettes for sale in Canada are now required to print 1 of 16 health warnings on each pack of

FIGURE 6-2 Example of one of Health Canada’s 16 graphic warnings.

SOURCE: (Health Canada 2005) http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/media/photogal/label-etiquette/img0010_e.html. Licensed under Health Canada copyright.

cigarettes (see Figure 6-2 for an example of such a warning). The new warning system extends to carton wrappers, which now include a warning on each of their six surfaces. The top 50 percent of each main panel on the package (as opposed to the side panel) must be used for the outside warning. These warnings include a photograph or other illustration, a marker word “Warning,” a short summary statement of the warning, and a brief explanation. Inside each pack, there must be 1 of 16 other detailed messages that provide information about quitting or health damage. Warning labels also include information on damage to nonsmokers exposed to smoke from cigarettes. Other tobacco products have similar requirements for warning labels.

Other Countries

Since 2001, several other countries have adopted graphic package warnings including Brazil, Singapore, Thailand, Australia, and Venezuela. Members of the European Union are now permitted, but not required, to prescribe graphic warnings, and the European Union has also developed a standard set of pictorial warnings for consideration by its members. Several other countries (Bangladesh, Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Taiwan) are currently considering graphic warnings. The World Health Organization Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (FCTC) requires that warnings cover 30 percent of the front and the back of the package and recommends package coverage of 50 percent or more. A series of messages must be rotated. Graphic warnings are permitted but are not required.

Package warning size and placement vary considerably by country. The front of the package is considered the most prominent location

(Cunningham 2005), and it is probably important to have some health message on all sides, since retailers may position packages to hide the warnings if all sides are not covered.

There are considerable variations in the types of graphics used and in potential emotional impacts of particular graphics. In Brazil, for example, the warnings are more colorful and more dramatic than the Canadian warnings, most showing smokers with obvious health conditions (see Figure 6-3).

FIGURE 6-3 Examples of Brazil’s graphic warnings.

SOURCE: See www.anvisa.gov.br/eng/informs/news/281003.htm.

Evidence Regarding Effectiveness

Ferrence and colleagues (Appendix C) have reviewed the scientific evidence regarding the effectiveness of tobacco package warnings in getting the attention of consumers and potential consumers (salience), influencing their awareness of tobacco-related health risks (risk perception), and affecting their self-reported smoking intentions and behaviors. In general, the evidence shows that the salience of warnings is affected by their placement, sizes, and other design features, and that salient warnings affect the consumer’s awareness of risks. Although few studies have been able to parse out the effects of warnings on smoking behavior, the available data suggest a beneficial effect on consumption and cessation.

For the committee’s present purposes, the question of greatest importance is what is known about the effects of pictorial warnings. Given that Canada was the first country to introduce pictorial warnings, all of the available evidence derives from Canadian smokers. A study conducted with Canadian smokers in 2001 found that more than half reported that the pictorial warnings have made them more likely to think about the health risks of smoking (Hammond et al. 2004). National surveys conducted on behalf of Health Canada also indicate that approximately 95 percent of youth smokers and 75 percent of adult smokers report that the pictorial warnings have been effective in providing them with important health information (Health Canada 2005a; Health Canada 2005b).

The International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey—a cohort survey of a representative sample of more than 8,000 adult smokers from Canada, Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom—also provides suggestive findings. When smokers were asked to cite the sources of smoking-related health information, approximately two-thirds of all smokers cited cigarette packages; this proportion was more than radio, print, and electronic sources, and cigarette packages were the second most common source after television (Hammond et al. 2005) However, the results varied substantially by country: respondents living in countries with more comprehensive warnings were more likely to cite packages as a source of health information. For example, 85 percent of Canadian respondents cited packages as a source of health information; in contrast, 47 percent of U.S. smokers cited packages as a source of health information. In addition, specific health warnings were associated with knowledge about specific diseases. For example, in Canada, where package warnings include information about the risks of impotence, smokers were more than twice as likely as smokers from the other three countries to agree that smoking causes impotence. Overall, the study found that warnings that are graphic, larger, and more comprehensive in content were associated with greater health knowledge.

Finally, there is evidence that smokers with less education are less likely to recall health information in text-based messages than people with more education (Millar 1996). Given the inverse association between smoking and educational status, pictorial warnings may be particularly important for communicating with those most at risk. Indeed, preliminary evidence suggests that countries with pictorial warnings demonstrate fewer disparities in health knowledge across educational levels (Siahpush et al. 2006). Pictorial warnings may also be particularly effective in educating people who are illiterate, and could have a significant population impact in developing countries with low literacy rates, as well as regions where numerous languages and dialects are used.

In a series of papers, Hammond and colleagues (2004) have examined the impact of Canadian graphic warning labels on smoking behavior. Smokers who had read, thought about, and discussed the new labels were more likely to have quit, tried to quit, or reduced their smoking at the 3-month follow-up, after adjustment for intention to quit and smoking status at baseline (Hammond et al. 2004). One-fifth of Canadian smokers said that they smoked less because of the labels, whereas only 1 percent said that they smoked more and one-third said that they were more likely to quit because of the warnings. In addition, former smokers identified the pictorial warnings as important factors in their quitting and in subsequently maintaining abstinence (Hammond et al. 2004). Results from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey are consistent with these findings: at least one quarter of respondents from Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States reported that package warnings have made them more likely to quit, although Canadian smokers were significantly more likely to report cessation benefits from the warnings than smokers in the other three countries that have text-only warnings (Fong et al. 2004).

As recommended in Growing Up Tobacco Free (IOM 1994) the proposed Tobacco Control legislation would strengthen the required package warnings immediately and would confer authority on the FDA to revise these requirements upon finding “that such a change would promote greater public understanding of the risks associated with tobacco.” (The 1994 committee stated that the agency should also be authorized to modify the warnings upon finding that so doing would reduce consumption, such as by making the risks more salient or strengthening the resolve of smokers to quit, and this committee agrees.) The bill would specifically authorize the agency to increase the required label area up to 50 percent of the package and to require color graphics. On the basis of the evidence accumulated thus far, graphic warnings of the kind required in Canada, Brazil, and Thailand “would promote greater public understanding of the risks” of using tobacco and would help reduce consumption.

Recommendation 26: Congress should strengthen the federally mandated warning labels for tobacco products immediately and should delegate authority to the FDA to update and revise these warnings on a regular basis upon finding that doing so would promote greater public understanding of the risks of using tobacco products or reduce tobacco consumption. Congress should require or authorize the FDA to require rotating color graphic warnings covering 50 percent of the package equivalent to those required in Canada.

Using Packages to Convey Other Health Information

Aside from printed health warnings, regulatory authorities can use the tobacco package to convey health-related information in other ways. For example, so-called package onserts (printed matter that is affixed to the package, and that is equivalent to inserts in drug product packaging) provide an appropriate vehicle for supplementing the health warnings printed on the package with information on ingredients and details regarding specific health hazards. In addition, the package can be used creatively to promote smoking cessation by displaying a quitline number and by including coupons for nicotine replacement products (e.g., patches and gum).

Recommendation 27: Congress should empower the FDA to require manufacturers to include in or on tobacco packages information about the health effects of tobacco use and about products that can be used to help people quit.

Restricting Misleading Messages on Tobacco Packages

Tobacco manufacturers have traditionally used the words and trademarks on the package as a channel for conveying messages about product characteristics. Some of these messages are misleading and are not protected by the First Amendment, because they falsely imply that smoking a particular brand of cigarette is less harmful than smoking other brands.

As Wakefield and colleagues (Wakefield et al. 2004) have noted, package design can help to shape perceptions of a tobacco product’s performance and its sensory attributes, even among experienced smokers. This phenomenon is best illustrated by the use of brand descriptors and colors to promote perceptions that the tobacco product is safer than other tobacco products. Tobacco manufacturers commonly pair brand descriptors such as “light” and “mild” with cigarettes that generate low tar yields under the machine testing protocols. Although the industry has argued that these terms refer only to the “taste” of a product, these descriptors help to promote these brands as “healthier” products (Pollay 2001; Pollay

and Dewhirst 2002). Indeed, surveys of smokers in the United States and Canada indicate that a substantial proportion of “light” cigarette smokers believe that their cigarettes are less hazardous (Kozlowski et al. 1998; Shiffman et al. 2001). Adolescents have also been found to have similar misconceptions that “light” cigarettes are less hazardous (Borland et al. 2004; Kropp and Halpern-Felsher 2004; see also Chapter 2).

Ashley and colleagues (2001) reported that in Ontario, Canada, in 1996, one in five smokers of “light” cigarettes incorrectly believed that smoking “light” and “mild” cigarettes lowered the risk of cancer and heart disease. In 2000, 27 percent of Ontario smokers said that they smoked “light” cigarettes to reduce health risks, 40 percent as a step toward quitting, and 41 percent said that they would be more likely to quit if they knew that “light” cigarettes provided the same amount of tar and nicotine as regular cigarettes (Ashley et al. 2001). In a study of smokers’ responses to advertisements for potentially reduced-exposure tobacco products, “light” cigarettes, and regular cigarettes, Hamilton and colleagues found that the respondents incorrectly perceived “light” cigarettes as having significantly lower health risks and carcinogen levels than regular cigarettes (Hamilton et al. 2004).

Article 11 of the FCTC calls for the removal of brand descriptors that “directly or indirectly create the false impression that a particular tobacco product is less harmful than other tobacco products,” including terms such as “low tar,” “light,” or “mild.” Several jurisdictions have already banned deceptive descriptors. For example, in September 2003, the European Union banned the use of a number of brand descriptors, such as “low-tar,” “light,” “ultra-light,” and “mild,” in accordance with Directive 2001/37/EC. Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey suggest that this ban has been effective in reducing misconceptions about the health benefits of brands labeled “light” and “mild” (Fong 2005). However, as the experience in the United Kingdom has demonstrated, tobacco manufacturers have proven adept at substituting numbers and colors for the banned descriptors. For example, pale blue and the number “one” are now being used to indicate a “light” or “mild” cigarette. In Brazil and the United Kingdom, manufacturers openly provided translation guides for this substitution. Because the evidence clearly shows that terms such as “mild,” “light,” “ultra-light,” and similar words are interpreted by consumers to imply reduced risk, the use of these terms should be barred.

In her recent remedial order in the federal government’s RICO suit against the big U.S. tobacco manufacturers, Judge Kessler permanently enjoined the companies from “conveying any express or implied health message or health descriptor for any cigarette brand either in the brand name or on any packaging, advertising or other promotional, informational or other

material.” She specifically enjoined use of the words “low tar,” “light,” “ultra-light,” “mild,” “natural,” and “any other words which reasonably could be expected to result in a consumer believing that smoking the cigarette brand using that descriptor may result in a lower risk of disease or be less hazardous to health than smoking other brands of cigarettes.” Judge Kessler’s order is very important, but it has two limitations: it does not apply to all manufacturers and it will require continuing interpretation regarding its application to words and images other than the ones specifically banned in the order.

The committee believes that Congress should supplement Judge Kessler’s order with a statutory restriction banning the use of these specific terms and should empower the regulatory agency to ban any other descriptors, signals, or practices that the companies may subsequently use that have the purpose or effect of leading consumers to believe believing that smoking the cigarette brand with that descriptor may result in a lower risk of disease or may be less hazardous to their health than smoking other brands of cigarettes.

Recommendation 28: Congress should ban, or empower the FDA to ban, terms such as “mild,” “lights,” “ultra-lights,” and other misleading terms mistakenly interpreted by consumers to imply reduced risk, as well as other techniques, such as color codes, that have the purpose or effect of conveying false or misleading impressions about the relative harmfulness of the product.

Using Packages to Convey Corrective Communications

Judge Kessler’s remedial order in the RICO suit also requires the defendant manufacturers to make various “corrective communications” on their websites, at the point of sale and on package inserts (Tobacco Free Kids 2006). These messages would address the adverse health effects of smoking, the addictiveness of smoking and nicotine, the effects of so-called low-tar cigarettes, the adverse effects of exposure to secondhand smoke, and the impact of marketing on youth smoking. Some of these proposed messages would be substantially equivalent to the health warnings contained in the proposed Tobacco Control legislation, although they would sometimes be more lengthy than package warnings. Some of the messages embody admissions of past deception by the manufacturers.

Recommendation 29: Whenever a court or administrative agency has found that a tobacco company has made false or misleading communications regarding the effects of tobacco products, or has engaged in conduct promoting tobacco use among youth or discouraging cessation

by tobacco users of any age, the court or agency should consider using its remedial authority to require manufacturers to include corrective communications on or with the tobacco package as well as at the point of sale.

THE RETAIL ENVIRONMENT FOR TOBACCO SALES SHOULD BE TRANSFORMED TO PROMOTE THE PUBLIC HEALTH

At present, tobacco use is actively promoted in retail outlets, with little regard to the public interest in discouraging smoking initiation (aside from the occasional warning sign that sale to a minor is prohibited) or in helping people quit. In the committee’s view, the retail environment for tobacco should be radically transformed. Effective measures of restricting the commercial distribution of tobacco products to youth are only a starting point. Tobacco is not an ordinary consumer product and should not be treated as such. Although the sale of tobacco products to adults is permitted, it is disfavored as a matter of public policy. The retail environment should be designed to effectuate the public health goals of discouraging tobacco use and reducing tobacco-related disease.

Current Retail Promotional Activities

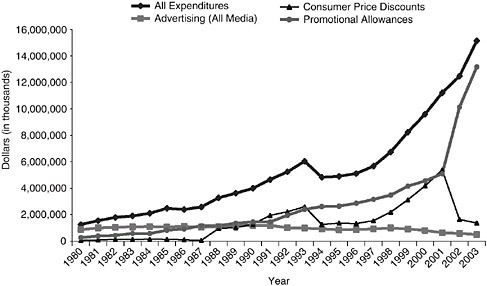

With the adoption of the MSA in 1998, there was a dramatic shift in the tobacco industry’s advertising and promotion budgets, and retail marketing became the dominant strategy (Pierce and Gilpin 2004). The categories of promotional expenditures by tobacco manufacturers since 1980, as reported to the FTC, are presented in Box 6-1 (see also Figure 6-4 and Table 6-1).

Point-of-Sale Advertising

In 2003, tobacco manufacturers spent $165.6 million in payments for the purchase of point-of-sale advertising (FTC 2005). The main venues of such advertising are convenience stores, small grocery stores (often in tandem with the sale of gas), liquor stores, chain supermarkets, and chain pharmacies, with youth exposure especially concentrated at the first two of these locations. The amount spent on point-of-sale advertising in 2003 represents a 41.7 percent decline from that in 2001, when companies spent $284.3 million on point-of-sale advertising, and a decline of 58.6 percent since their peak in 1993 at $400.9 million (FTC 2005). The prime advertising space within most retail stores is the radius around the checkout counter. A study conducted in California found nearly 90 percent of tobacco marketing materials within 4 feet of store checkout counters (Feighery et

|

BOX 6-1 Domestic Cigarette Advertising and Promotional Expenditures for 2003 (Dollars in Thousands)

NOTE: The twenty-four spending categories are listed as they appear in the Federal Trade Commission’s Cigarette Report for 2003. The Committee designated the four main expenditure groups and which spending categories were included in each. |

al. 2001). A similar study found that nearly 50 percent of the California retailers surveyed posted tobacco product advertisements 3 feet or lower in height, which is easy eye-level for young children.

Under current law, state restriction of tobacco advertising (“based on smoking and health”) at the point of sale is preempted by the 1969 Ciga-

FIGURE 6-4 Domestic cigarette advertising and promotional expenditures for 1980–2003.

rette Labeling Act. However, the committee believes that the states should be free to regulate advertising at the point of sale as long as the regulation is no less restrictive than whatever federal regulation may have been adopted. In fact, this is the approach taken in the proposed Tobacco Control legislation, which would allow the states to ban point-of-sale advertising and other restrictions that would have been preempted under the Cigarette Labeling Act.

Retail Promotional Allowances

Promotional allowances paid to retailers now constitute the lion’s share of manufacturers’ marketing expenditures (see Figure 6-4 and Table 6-1). They are broadly defined by the FTC to include all payments or allowances to retailers “in order to facilitate the sale of any cigarette.” So defined, they include so-called slotting fees, which are industry fees paid to retailers—in the form of discounts—linked to advantageous placement and promotion vis-à-vis competing brands. In addition to product placement itself, these merchandising strategies address an array of product accessories: signage (e.g., regarding discount deals), logos, banners, display racks, and window posters. Another type of retail allowance involves pricing policies. So-called buy-downs feature inventory clearance deals, which are time-constrained discounts. To participate in the buy-down, a retailer must agree to erect special product displays and other promotional signs. In addition to buy-

TABLE 6-1 Promotional Expenditures by Tobacco Manufacturers

downs, there is the most basic of pricing strategies: straight volume discounts for retailers.

Although these practices are common marketing practices for other retail goods, such as food and soft drinks, they are problematic from a tobacco control standpoint for two reasons. First, when the manufacturers purchase display space or other promotional services from the retailer, they are promoting smoking as well as the use of the particular brands displayed or advertised. As discussed below, the committee believes that, aside from properly restrained black-and-white–text only price advertising, all promotional displays should be prohibited, including so-called power walls (large displays of packages of a single brand).

Second, the purchase of space through the payment of slotting fees could reduce or even eliminate the space available for smaller manufactur-

ers who are producing PREPs and who cannot afford to pay the same fees or give similar discounts as the major manufacturers. Even if this practice does not amount to an antitrust violation, it certainly tends to reduce the available shelf space for brands with the smallest market share, such as PREPs introduced by new entrant firms. In the committee’s view, the overall public health objective of reducing tobacco use justifies the more aggressive regulation of retail marketing and sales practices. Instead of allowing market forces to give prioritized access to ordinary tobacco products, society should direct retailers who choose to sell tobacco products to give prioritized display space to products that tend to reduce tobacco-related disease, including smoking cessation products and, as they are introduced, to tobacco products that have been found to have genuine potential for reducing tobacco-related disease.

Recommendation 30: Congress and state legislatures should enact legislation regulating the retail point of sale of tobacco products for the purpose of discouraging consumption of these products and encouraging cessation. Specifically:

-

All retail outlets choosing to carry tobacco products should be licensed and monitored (see also youth access section in Chapter 5).

-

Commercial displays or other activity promoting tobacco use by or in retail outlets should be banned, although text-only informational displays (e.g., price or health-related product characteristics) may be permitted within prescribed regulatory constraints.

-