5

Preventing Cancers (and Other Diseases) by Reducing Tobacco Use

Cigarette smoking and other forms of tobacco use impose a large and growing global public health burden. Worldwide, tobacco use kills nearly 5 million people annually—about one third from cancer and two thirds from other diseases—accounting for 1 in every 5 male deaths, and 1 in 20 female deaths, over age 30. On current smoking patterns, annual tobacco deaths will rise to 10 million by 2030, about 3 million of which will be from cancer. If current smoking patterns persist, with about 30 percent of all young adults (50 percent of men and 10 percent of women) becoming smokers and most not giving it up, then the 21st century is likely to see 1 billion tobacco deaths, most of them in today’s developing countries. In contrast, the 20th century saw 100 million deaths caused by tobacco, most of them in developed countries.

This report is about cancer control. In the case of tobacco, however, cancer is just one of the ways in which tobacco kills, and interventions to reduce tobacco use will have much broader benefits than just in terms of cancer. In this chapter the health effects of tobacco—overwhelmingly cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and respiratory diseases—and the benefits of stopping tobacco use are considered together, not separately.

Before discussing the interventions that can reduce tobacco use, the landmark Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) is introduced. Global tobacco control efforts have been unified by the FCTC, an international treaty negotiated by the World Health Organization (WHO). The treaty calls for tobacco control measures that are firmly rooted in evidence, and creates an organization of all parties to monitor its progress and promote its implementation. This report recommends that all countries

TABLE 5-1 Estimated Smoking Prevalence (by gender) and Number of Smokers, 15 Years of Age and Over, by World Bank Region, 2000

|

|

Smoking Prevalence (percentage) |

Total Smokers |

|||

|

World Bank Region |

Males |

Females |

Overall |

Millions |

Percentage of All Smokers |

|

East Asia and Pacific |

63 |

5 |

34 |

429 |

38 |

|

Europe and Central Asia |

56 |

17 |

35 |

122 |

11 |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

40 |

24 |

32 |

98 |

9 |

|

Middle East and North Africa |

36 |

5 |

21 |

37 |

3 |

|

South Asia |

32 |

6 |

20 |

178 |

15 |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

29 |

8 |

18 |

56 |

6 |

|

Low and middle income |

49 |

8 |

29 |

920 |

82 |

|

High income |

37 |

21 |

29 |

202 |

18 |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Jha et al. (2006). Copyright 2006 by the World Bank. |

|||||

ratify the FCTC, which requires them to implement its provisions. The evidence supporting the interventions recommended by the FCTC are reviewed later in this chapter. One caveat for this chapter is that the evidence on the effectiveness of interventions is largely from studies and programs in high-income countries. In recent years, some more research has been conducted in LMCs, but overall, the body of this evidence is relatively small. The assumption is made that behavior will be similar in LMCs and high-income countries, but clearly, direct observation and study in those countries is needed to ensure that interventions are working and, if not, new approaches are developed to respond to local conditions.

PREVALENCE AND EFFECTS OF SMOKING1

Smoking Prevalence

More than 1.1 billion people worldwide smoke tobacco. Smoking prevalence is highest in Europe and Central Asia (35 percent of adults), but overall, about 82 percent of smokers are in LMCs (Table 5-1) (Jha et al., 2006). Globally, male smoking far exceeds female smoking; the gender difference is smallest in high-income countries.

While overall smoking prevalence continues to increase in many LMCs, many high-income countries have witnessed decreases, most clearly in men. A study in 36 mostly western countries, from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, suggested that the decrease in smoking prevalence among men was due both to the lower prevalence of starting smoking in younger age groups, as well as adults quitting smoking. Among women, there was little overall change in smoking prevalence because the increasing prevalence of smokers in younger age cohorts counterbalanced increasing cessation in older age groups (Molarius et al., 2001).

Health Consequences of Smoking

It is often taken for granted that the harm done by tobacco is well understood. But the magnitude of tobacco’s harm is widely underestimated. More than 50 years of epidemiologic study of smoking-related diseases have led to three key messages for individual smokers and for policy makers (Doll et al., 2004; Peto et al., 2003). They are:

-

The eventual risk of death from smoking is high, with about one-half of long-term smokers eventually dying from their addiction.

-

About half of all tobacco deaths occur between ages 35 and 69—in middle age—about 20 to 25 years sooner than the deaths of nonsmokers.

-

Cessation works: Adults who quit before middle age avoid almost all the excess hazards of continued smoking.

The evidence is heavily weighted toward high-income countries, so it is not surprising that governments and individuals in LMCs have found it less relevant. However, as more studies are undertaken in those countries, a similar picture emerges, with somewhat different local details, depending on the other major risk factors and patterns of death. Studies in a wide range of countries, preferably long-term prospective studies (see Chapter 3), are needed to increase our understanding of these details and to tailor tobacco control interventions and messages.

Current Mortality from Smoking and Future Projections

An estimated 5 million deaths were caused by tobacco in 2000 (Ezzati and Lopez, 2003), about half (2.6 million) in low-income countries. Males accounted for 3.7 million deaths, three quarters of the total. About 60 percent of male and 40 percent of female tobacco deaths occurred in middle age (ages 35 to 69).

The patterns of causes of these deaths differ between high- and low-income countries. In high-income countries and former socialist economies,

nearly half (450,000) of the 1 million middle-aged male tobacco deaths were from cardiovascular disease, and about half that number (210,000) from lung cancer. In contrast, in low-income countries, the leading causes of death among the 1.3 million male tobacco deaths were cardiovascular disease (400,000), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (200,000), other respiratory disease (chiefly tuberculosis, 200,000) and lung cancer (180,000).

Future increases in tobacco deaths worldwide are expected to arise from increased smoking by men in developing countries, and by women worldwide. The increases will be a product of population growth and increased age-specific tobacco mortality rates, the latter relating to both smoking duration and the amount of tobacco smoked. Peto and others (Peto et al., 1994) have made the following calculation: If the proportion of young people taking up smoking continues to be about half of men and 10 percent of women, then there will be about 30 million new long-term smokers each year. Half of these smokers will eventually die from smoking. However, conservatively assuming that “only” about one-third of smokers die as a result of smoking, then smoking will eventually kill about 10 million people a year. Thus, for the 25-year period from 2000 to 2025, there will be about 150 million tobacco deaths or about 6 million deaths per year on average; from 2025 to 2050, there will be about 300 million tobacco deaths, or about 12 million deaths per year.

Further estimations are more uncertain, but based on current smoking trends and projected population growth, from 2050 to 2100 there will be an additional 500 million tobacco deaths. These projections for the next three to four decades are comparable to retrospective and early prospective epidemiological studies in China (Liu et al., 1998; Niu et al., 1998), which suggest that annual tobacco deaths will rise to 1 million before 2010 and 2 million by 2025, when the young adult smokers of today reach old age. Similarly, results from a large retrospective study in India suggest that 1 million annual deaths are expected from male smokers by 2025 (Gajalakshmi et al., 2003). With other populations in Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and, less certainly, sub-Saharan Africa showing similar growth in population- and age-specific tobacco death rates, the estimate of some 450 million tobacco deaths over the next five decades appears to be plausible.

Benefits of Smoking Cessation

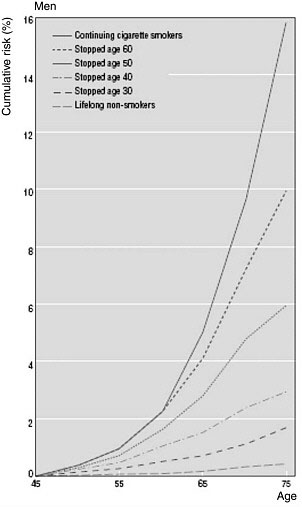

Smoking cessation reduces the risk of death from all tobacco-related diseases. The study of smoking habits, including cessation, with the longest follow-up is of doctors in the United Kingdom. Of those doctors who stopped smoking, the risk of lung cancer fell steeply over time (Doll et al., 2004; Peto et al., 2000) (Figure 5-1). These results are mirrored in a recent multicenter study of men in four European countries, which found that

FIGURE 5-1 Stopping works: Cumulative risk of lung cancer mortality in U.K. males, 1990 rates.

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Peto et al., 2000. Copyright 2000 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

quitting smoking at age 40 avoided 80 to 85 percent of the excess risk of lung cancer (Crispo et al., 2004). Smoking cessation is uncommon in most developing countries, but there is some evidence that, among Chinese men, quitting also reduces the risks of dying from all causes together and at least from vascular disease specifically (Lam et al., 2002). Among doctors in the United Kingdom, the benefits of quitting were greatest in those who quit

before middle age, but were still significant in those who quit later (Doll et al., 2004).

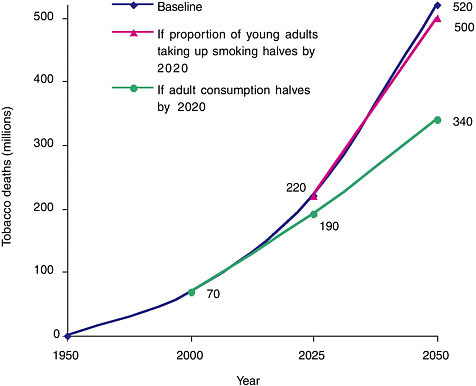

Current tobacco mortality statistics reflect past smoking behavior, given the long delay between the onset of smoking and the development of disease. The only way to prevent a substantial proportion of tobacco deaths before 2050 is for adult smokers to stop. For example, if the per-capita adult consumption of tobacco (mainly from people quitting entirely) could be cut in half by 2020 (akin to the declines in adult smoking in the United Kingdom), about 180 million premature tobacco deaths would be averted. Continuing to reduce the percentage of children who start to smoke will prevent many deaths, but its main effect will be on mortality rates in 2050 and beyond (Figure 5-2) (Jha and Chaloupka, 2000a; Peto and Lopez, 2002).

FIGURE 5-2 Tobacco deaths in the next 50 years under current smoking patterns.

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Jha and Chaloupka, 2000a. Copyright 2000 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON TOBACCO CONTROL

The FCTC is a pillar in tobacco control. The FCTC, adopted by the World Health Assembly (WHA), the WHO governing body, in May 2003, is the world’s first global health treaty (WHO, 2003). The idea for an international instrument for tobacco control first arose at the annual WHA in 1995, in response to the globalization of tobacco and the increases in tobacco use, particularly among women and in LMCs. The following year, the WHA adopted a resolution calling for the WHO Director-General to initiate development of a Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Work did not begin in earnest until 1999, and was adopted by the WHA and then opened for signatures in June 2003 and remained open until June 29, 2004.

The treaty came into force in February 2005, 90 days after the 40th country (Peru) had signed and ratified it. Countries that have ratified the FCTC are obligated, under international law, to enact its provisions. Countries that did not sign the treaty can still join by “accession,” a one-step process equivalent to ratification. As of July 2006, 134 countries, including 108 LMCs, had become parties to it by ratification or the legal equivalent (accession, acceptance, approval, or formal confirmation). A total of 52 countries (including the United States) have signed but not ratified the FCTC (WHO, 2006).

Entering into force triggered another provision of the FCTC, which was the first meeting of the “Conference of the Parties,” a formal body on which all signatories are represented, to be held within one year. The 2-week meeting took place in February 2006. The conference will meet regularly to review national reports and generally promote the FCTC, including promoting the financial aspects of treaty activities.

The FCTC includes provisions for both demand reduction and supply reduction, based on sound evidence that they are effective in reducing tobacco use. Key provisions are the following:

-

Advertising, sponsorship, and promotion

Parties to the treaty must ban tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship, as far as permitted by their constitutions. Where constitutions do not allow this, restrictions on all advertising, promotion, and sponsorship must be adopted.

-

Packaging and labeling of tobacco products

The treaty obligates parties to adopt and implement large, clear, visible, legible, and rotating health warnings and messages on tobacco products and their outside packaging, occupying at least 30 percent of the principal display areas.

-

Protection from exposure to tobacco smoke

Parties must adopt and implement (in areas of national jurisdiction)

or promote (at other jurisdictional levels) effective measures to prevent exposure to tobacco smoke in indoor workplaces, public transport, indoor public places, and, as appropriate, other public places.

-

Illicit trade in tobacco products

Parties must adopt and implement effective measures to eliminate illicit trade, illicit manufacturing, and counterfeiting of tobacco products.

INTERVENTIONS TO PREVENT SMOKING

Hundreds of millions of premature tobacco deaths could be avoided if effective interventions were applied widely in LMCs. The measures that have proven effective in reducing tobacco use, mainly in high-income countries thus far, are: tobacco tax increases, timely dissemination of information about health risks from smoking, restrictions on smoking in public places and workplaces, comprehensive bans on advertising and promotion, and increased access to cessation therapies. Price and nonprice interventions are, for the most part, highly cost-effective in high-income countries, with less evidence available from LMCs. The interventions discussed here are divided into those aimed at reducing the demand for tobacco and those aimed at reducing tobacco supply.

Interventions to Reduce Demand for Tobacco

The following sections review the evidence on the impact of interventions to reduce demand for tobacco, including a discussion of each intervention’s effect on initiation of smoking and smoking cessation. As has been stated, much of the evidence is from high-income countries.

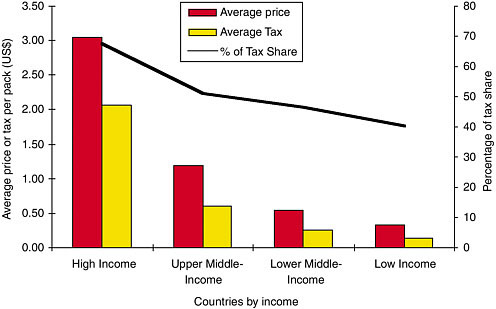

Tobacco Taxation

Nearly all governments tax tobacco products, but at widely varying levels. In some places, taxes are specific or per unit, and elsewhere, they are expressed as a percentage of wholesale or retail prices (ad valorem taxes). Taxes tend to be absolutely higher and account for a greater share of the retail price (two-thirds or more) in high-income countries (Figure 5-3). Tobacco taxes are much lower, and account for less than half of the final price of cigarettes, in most LMCs.

More than 100 studies from high-income countries clearly demonstrate that increases in taxes on cigarettes and other tobacco products lead to significant reductions in cigarette smoking and other tobacco use (Chaloupka et al., 2000). The reductions in tobacco use that result from higher taxes and prices reflect the combination of increased smoking cessation, reduced relapse, lower smoking initiation, and decreased consumption among

FIGURE 5-3 Average cigarette price, tax, and percentage of tax share per pack, by income group, 1996.

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Jha et al. (2006). Copyright 2006 by the World Bank.

continuing tobacco users. Studies of price elasticity of demand (i.e., how sensitive sales volume is to price) from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and other high-income countries have generally produced estimates that range from –0.25 up to an upper limit of –0.50, indicating that a 10 percent increase in cigarette prices could reduce overall cigarette smoking by 2.5 percent to 5 percent (Chaloupka et al., 2000; Gallus et al., 2006; U.S. DHHS, 2000).

Studies from LMCs have produced mixed results, however, some suggesting a greater price elasticity in such countries (Jha et al., 2006) while others suggest a smaller effect in some LMCs. A study in China and Russia, for example, using longitudinal data (as opposed to most studies, which have used aggregate data) found price elasticity estimates ranging from 0 to –0.15 (i.e., including a possibility of no effect) (Lance et al., 2004). Laxminarayan and Deolalikar (2004) examined the impact of tobacco prices on decisions to begin or quit smoking in Vietnam, using household survey data from the early and late 1990s. They found that decisions may be more complex than in high-income countries because a larger array of tobacco products—including nonmanufactured, local products—enlarges the choices people may

make. Higher cigarette prices might divert smokers to products that are less expensive, but potentially equally detrimental to health.

Studies using survey data have concluded that half or more of the effect of price on overall cigarette demand results from reducing the number of current smokers (U.S. DHHS, 1994; Wasserman et al., 1991). Higher taxes increase both the number of attempts at quitting smoking and the success of those attempts (Tauras and Chaloupka, 2003). A study in the United States (Tauras, 1999) suggested that a 10 percent increase in price would result in an 11 to 13 percent shorter smoking duration or a 3.4 percent higher probability of cessation.

According to recent studies, there is an inverse relationship between price elasticity and age, with estimates for youth price elasticity of demand up to three times those of adults (Gruber, 2003; Ross et al., 2001). Several recent studies have begun to explore the differential impact of cigarette prices on youth smoking uptake, concluding that higher cigarette prices are particularly effective in preventing young smokers from moving beyond experimentation into regular, addicted smoking (Emery et al., 2001; Ross et al., 2001).

In the United States and the United Kingdom, increases in the price of cigarettes have had the greatest impact on smoking among the lowest income and least educated populations (Townsend et al., 1994; U.S. DHHS, 1994). Furthermore, it was estimated that smokers in U.S. households below median income level are four times more responsive to price increases than smokers in households above median income level.

Overall, the evidence strongly supports the premise that price affects behavior, in many cases very strongly. However, the evidence is still largely from high-income countries. It cannot be assumed that the impacts will be the same in LMCs, where so many aspects of life differ from those in high-income countries. As more evidence directly relevant to LMCs accumulates, patterns may emerge that reflect differences from the effects seen in high-income countries. Policy decisions should improve as more such information becomes available. The current recommendation of the FCTC, to increase tobacco taxes, is still well supported, but the magnitude of the impact and the specifics of effects appear likely to vary from place to place, possibly very considerably.

Restrictions on Smoking

Over the past three decades, as the quantity and quality of information about the health consequences of exposure to passive smoking has increased, many governments, especially in high-income countries, have restricted smoking in a variety of public places and private worksites. Increased concern about the consequences of passive smoking exposure,

particularly to children, has led many workplaces to adopt voluntary restrictions on smoking. These restrictions reduce nonsmokers’ exposure to passive tobacco smoke, but also reduce smokers’ opportunities to smoke. Additional reductions in smoking, especially among youth, will result from the changes in social norms that are introduced by adopting these policies (U.S. DHHS, 1994).

In high-income populations, comprehensive restrictions on cigarette smoking reduced population smoking rates, possibly by as much as 5 to 15 percent (see Woolery et al. [2000] for a review of the effects of indoor smoking bans on youth smoking rates; see Levy et al. [2001]) for the results of simulation modeling of the impacts of smoking bans). As with higher taxes, both the prevalence of smoking and cigarette consumption among current smokers are reduced. According to Levy and colleagues (2001), no-smoking policies are most effective when strong social norms against smoking help to make smoking restrictions self-enforcing. The evidence is not entirely consistent with overall smoking declines as a result of smoking bans, however. A recent systematic review of workplace interventions for smoking cessation (Moher et al., 2005) included a subset of studies of indoor smoking bans that confirmed the decrease in smoking at work by smokers, and a corresponding decrease of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. The evidence was less clear, however, about an overall decrease in smoking.

The applicability of findings related to smoking restrictions in high-income countries to conditions in LMCs is, as for other aspects, somewhat uncertain. Smoking bans are still rare in LMCs, so little to no direct evidence is yet available. To the extent that workplaces themselves differ between high-income countries and LMCs, different results might be expected. Nonetheless, the existing evidence should be sufficient to support the FCTC recommendation of smoking bans wherever feasible, with the caveat that impacts should be evaluated.

Health Information and Counteradvertising

The 1962 report by the British Royal College of Physicians and the 1964 U.S. Surgeon General’s Report were landmark tobacco control events. These publications resulted in the first widespread press coverage of the scientific links between smoking and lung cancer. The reports were followed, in many high-income countries, by policies requiring health warning labels on tobacco products, which were later extended to tobacco advertising. The message did reach some LMCs as well, such as Malaysia (Box 5-1), with little delay.

Research from high-income countries indicates that these initial reports and the publicity that followed about the health consequences of smoking led to significant reductions in consumption, with initial declines of between

|

BOX 5-1 Tobacco Control in Malaysia Malaysia has a long history of tobacco control campaigns, beginning in the 1970s. The Cancer and Tobacco unit in the Ministry of Health (MOH) is the government focal point for tobacco control. The vision of this unit is that by the year 2020, tobacco will no longer be a major public health concern in Malaysia, where decreasing national prevalence of tobacco use will be halved and tobacco-attributed illnesses and mortality will continuously decline. In 1972, the MOH and the Malaysian Medical Association jointly established the Action on Smoking on Health Committee (ASH). In 1992, cigarette taxes were increased by 100 percent. Import and excise duties were doubled in 1993 to $11.44 per kg. All direct advertising of tobacco is prohibited, but brand name stretching (the use of tobacco brand names on non-tobacco merchandise or services) is still allowed, and advertising is permissible in any imported print media. Cigarette packets bear a single fixed health warning. Tobacco sales to any person under 18 years are prohibited, as are vending machines. Smoking is banned in government offices, prisons, amusement centers, theaters, hospitals and clinics, public elevators, air-conditioned restaurants (with some exceptions), and public transportation. Antismoking Campaigns Since 1970, regular antismoking campaigns have been organized by schools, the Ministry of Health, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as the Malaysian Medical Association and consumer associations. Information on the dangers of smoking to pregnant women is distributed through pamphlets, posters, and health talks. Articles on smoking and health appear regularly in the media. A national antismoking campaign—“Tak Nak Merokok” or “No to Tobacco”—was launched with fanfare by the Prime Minister in February 2004, funded by government at 20 million Malaysian Ringgits (about $5.4 million) per year for 5 years. Despite huge banners and screaming television coverage of the antismoking campaign, results have not yet been seen. While other antismoking campaigns have tried to sell the idea that smoking was unhealthy and “uncool,” the “Tak Nak” campaign is about the need to look good, which is even more important to today’s young people (e.g., by displaying posters of people with smoking-damaged teeth). NGOs are also active in antismoking campaigns. In June 2004, the Malaysian Association of Youth Clubs launched the Youth Smoking Prevention Media Campaign, building on a previous government campaign. It is designed to address the misconceptions among the younger generation that smoking is hip, cool, and trendy. This campaign was sponsored by two major tobacco companies, the British-American Tobacco Company |

|

and JT International, as part of a trend in tobacco company sponsorship of antismoking campaigns. There is no evidence that youth smoking prevention campaigns sponsored by the tobacco industry have been effective. However, the 2004 campaign was used by the tobacco companies to strengthen their waning public credibility and to influence the government. Tobacco transnationals have been notorious for using aggressive advertising and promotional tactics not allowed at home. Malaysia, for example, has come to be known as the world capital for indirect advertising used by the transnationals. Brand-stretching activities and sponsorship of sports and entertainment events has remained legal and extremely widespread. With more aggressive control on advertising by tobacco companies, Malaysia should no longer be known for such tactics. Smoking Prevalence Despite antismoking activities, smoking prevalence continued to increase from 1986 through 2000, according to surveys in those years and in 1996. In 2000, just about half of all adult males smoked, as did about 5 percent of females. Peak age groups for smoking were 25–29 and 60–64. The age when their smoking began was lower among younger than older smokers, and younger among males (average age 19.5 years) than females (average age 24.7 years). Indigenous groups (29.1 percent) and the Malays (27.9 percent) had the highest smoking prevalence, while the Indians (16.2 percent) and the Chinese |

4 and 9 percent, and longer term cumulative declines of 15 to 30 percent (Kenkel and Chen, 2000; Townsend, 1993). Efforts to disseminate information about the risks of smoking and of other tobacco use in LMCs have led to similar declines in tobacco use in these countries (Kenkel and Chen, 2000). In addition, mass media antismoking campaigns, in many cases funded by earmarked tobacco taxes, have generated reductions in cigarette smoking and other tobacco usage (Kenkel and Chen, 2000; Saffer, 2000). Decreases in smoking prevalence are greatest in countries where the public is constantly and consistently reminded of the dangers of smoking by coverage of issues related to tobacco in the news media (Molarius et al., 2001).

In many LMCs, the public has not been well informed about the health risks of smoking. A national survey in China in 1996 found that 61 percent of smokers thought tobacco did them “little or no harm” (Chinese Academy of Preventive Medicine, 1997). In high-income countries, smokers are aware of the risks, but a recent review of psychological studies found that few smokers judge the size of these risks to be higher and more established

|

(19.2 percent) were less likely to smoke. Smoking was highest among those with only primary-level education (35.1 percent) and lowest in the highest educated group (23.1 percent). Smoking was also higher in lower income households. The professional and clerical occupational groups had the lowest rates (25.5 percent and 21 percent respectively), while the highest rates were in the agricultural occupations (56.4 percent). Legislation In 2005, the Cabinet approved a stand-alone Tobacco Control Act to take effect in the next 2 years. The Act will replace the Control of Tobacco Products Regulation 1993 (CTPR93) as the comprehensive tobacco control legislation in Malaysia, incorporating all relevant provisions and country obligations stated in the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, which was signed by Malaysia in 2003. Until then, CTPR93 will remain the most important antismoking legislation. Among its provisions (which have been strengthened since passage) are:

SOURCE: Hamzah (2005). |

than do nonsmokers, and that smokers minimize the personal relevance of these risks (Weinstein, 1998).

Bans on Advertising and Promotion

Cigarettes are among the most heavily advertised and promoted products in the world. In 2001, cigarette companies spent $11.2 billion on advertising and promotion in the United States alone, the highest spending level reported to date (Federal Trade Commission, 2003). Tobacco advertising efforts worldwide include traditional forms of advertising through television, radio, billboards, magazines, and newspapers; favorable product placement; price-related promotions, such as coupons and multipack discounts; and sponsorship of highly visible sporting and cultural events.

The evidence is somewhat mixed about the effect of cigarette advertising and promotion on demand for cigarettes. Survey research and experiments that assess reactions to and recall of cigarette advertising find that increases

in cigarette advertising and promotion directly and indirectly increase demand and smoking initiation (U.K. Department of Health, 1992; U.S. DHHS, 1994). Others have concluded that “the weight of the evidence from the academic literature suggests that advertising does not play a significant role in smoking initiation” (Taylor and Bonner, 2003). At least in part, the uncertainties arise from the difficulty of measuring the effects of advertising. One analyst points out that controlled, randomized experiments where some youth are exposed to cigarette advertising and others are not, are not possible, nor is it possible it isolate changes in advertising from other factors (e.g., societal attitudes) that are changing simultaneously (Goldberg, 2003). The types of studies that can be done, e.g., correlations between smoking behaviors and advertisement recall and awareness, are subject to different sorts of potential biases that arise from self-reported opinions and recall.

Econometric studies, mostly from the United States and the United Kingdom, have studied the effect of marginal changes in expenditures for advertising, concluding that at most, they have a small a small impact on demand (Chaloupka et al., 2000; Federal Trade Commission, 2003; Townsend, 1993).

Further studies of advertising and promotion bans should provide more direct evidence on the effect of these measures (Saffer, 2000). One study using data from 22 high-income countries for the period 1970 through 1992 provides some evidence that comprehensive bans on cigarette advertising and promotion led to significant reductions in cigarette smoking. The study predicted that a comprehensive set of tobacco advertising bans in high-income countries could reduce tobacco consumption by more than 6 percent, taking into account price and nonprice control interventions (Saffer and Chaloupka, 2000). The study concludes, however, that partial bans have little impact on smoking behavior, given that the tobacco industry can shift its resources from banned media to other media that are not banned.

Smoking Cessation Treatments

Near-term reductions in smoking-related mortality depend heavily on smoking cessation. There are many approaches to smoking cessation, including self-help manuals, community-based programs, and minimal or intensive clinical interventions (U.S. DHHS, 2000). In clinical settings, pharmacological treatments, including nicotine replacement therapies (NRT) and bupropion, have become much more widely available in recent years in high-income countries through deregulation of some NRTs from prescription to over-the-counter status (Curry et al., 2003; Novotny et al., 2000; U.S. DHHS, 2000). The evidence is strong and consistent that pharmacological treatments significantly improve the likelihood of quitting, with success rates two to three times better than without pharmaceutical treatments (Novotny

et al., 2000; Raw et al., 1999; U.S. DHHS, 2000). The effectiveness of all commercially available NRTs seems to be largely independent of the duration of therapy, the setting in which the NRT is provided, regulatory status (over-the-counter versus prescribed), and the type of provider (Novotny et al., 2000). Over-the-counter NRTs without physician oversight have been used in many countries for a number of years with good success.

Ironically, the markets for NRT and other antismoking pharmacological therapies are more highly regulated and less affordable than are cigarettes and other forms of tobacco. Recent evidence indicates that the demand for NRT is related to economic factors, including price (Tauras and Chaloupka, 2003). A systematic review of the few studies of policies to cover (or decrease) the cost of NRT to the consumer—such as mandating private health insurance coverage of NRT, including NRT coverage in public health insurance programs, and subsidizing NRT for uninsured or underinsured individuals—does conclude that these policies increase the (self-reported) rate of quitting and sustained abstinence, but the evidence base is small (Kaper et al., 2005).

Interventions to Reduce the Supply of Tobacco

The key intervention on the supply side is the control of smuggling. Recent estimates suggest that 6 to 8 percent of cigarettes consumed globally are smuggled (Merriman et al., 2000). Of note, the tobacco industry itself has an economic incentive to smuggle, in part to increase market share and decrease tax rates (Joossens et al., 2000; Merriman et al., 2000). While differences in taxes and prices across countries create a motive for smuggling, a recent analysis comparing the degree of corruption in individual countries with price and tax levels found that corruption within countries is a stronger predictor of smuggling than is price (Merriman et al., 2000). Several governments are adopting policies aimed at controlling smuggling. In addition to harmonizing price differentials between countries, effective measures include prominent tax stamps and warning labels in local languages, better methods for tracking cigarettes through the distribution chain, aggressive enforcement of antismuggling laws, and stronger penalties for those caught violating these laws (Joossens et al., 2000). Recent analysis suggests that even in the presence of smuggling, tax increases will reduce consumption and increase revenue (Merriman et al., 2000).

The evidence that interventions aimed at reducing the supply of tobacco products are effective in reducing cigarette smoking is much weaker than it is for demand-side interventions (Jha and Chaloupka, 1999, 2000b). The U.S. experience provides mixed evidence about the effectiveness of limiting youth access to tobacco products in reducing tobacco use (U.S. DHHS, 2000; Woolery et al., 2000). In addition, the effective implementation and

enforcement of these policies may require infrastructure and resources that do not exist in many LMCs. A preliminary discussion is occurring in Canada about reducing the number of retail outlets for tobacco from its current 65,000. The potential effect of such a move, and its enforcement costs, are not yet known. Crop substitution and diversification programs are often proposed as a means to reduce the supply of tobacco. However, there is little evidence that such programs would significantly reduce the supply of tobacco, given that the incentives for growing tobacco tend to attract new farmers who would replace those who abandon tobacco farming (Jacobs et al., 2000). Similarly, direct prohibition of tobacco production is not likely to be politically feasible, effective, or economically optimal. Finally, while trade liberalization has contributed to increases in tobacco use, particularly in LMCs, restrictions on trade in tobacco and tobacco products that violate international trade agreements or draw retaliatory measures (or both) may be more harmful.

Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Tobacco Control Interventions: Projections from a Model

Jha and colleagues (2006) estimated the effect that various interventions to reduce tobacco supply and demand would have on deaths due to smoking, with separate estimates for low- and for middle-income countries. The details of this model have been published previously (Ranson et al., 2002). Based on a cohort of smokers alive in 2000, they estimated the number of smoking-attributable deaths over the next few decades that could be averted by (1) price increases, (2) NRT, and (3) a package of nonprice interventions other than NRT (e.g., advertising and promotion bans, mass information, and warning labels). The data available for use in this model (and other such models) are from high-income countries. The model takes a public policy perspective in that the costs included are only those incurred by the public sector. Costs to individuals (e.g., out-of-pocket costs for such things as NRT, or the time costs of accessing interventions) are not included. The model does not take a “societal” perspective, which would include costs to all others affected. Effectiveness was estimated as years of healthy life saved, measured in disability adjusted life years (DALYs). The analysis is conservative in its assumptions about effectiveness (i.e., may underestimate effectiveness) and generous in its assumptions about the costs of tobacco control (i.e., may overestimate costs). This model is the most comprehensive of its type available, and the only one that attempts to make estimates separately for low- and middle-income countries for a range of interventions. It should be kept in mind that these are just estimates. The inputs to the model are, as stated, largely from high-income countries, where relationships may

be somewhat different, so the results should be taken only as approximate indicators of what might be expected.

Potential Impact of Price Increases

The effect of increasing cigarette prices by 33 percent, 50 percent, and 70 percent were estimated. With a 33 percent increase, the model predicts that 22 million to 65 million smoking-attributable deaths would be averted worldwide, approximately 5 to 15 percent of all smoking-attributable deaths expected among those who smoke in 2000 (Table 5-2). Ninety percent of the deaths averted would be in low- and middle-income countries. Roughly 40 percent of the averted deaths would be in East Asia and the Pacific. For a 50 percent increase, worldwide smoking-attributable deaths averted range from 33 million to 92 million, and for a 70 percent price increase, 46 million to 114 million deaths (10 to 26 percent of all smoking-attributable deaths) would be averted.

Of the tobacco-related deaths that would be averted by a price increase, 80 percent would be male, reflecting the higher overall prevalence of smoking in men. The greatest relative impact of a price increase on deaths averted is among younger age cohorts. The price increases used in the model are achievable, and may even be conservative. In certain countries, such as South Africa and Poland, recent tax increases have doubled the real price of cigarettes (Guindon et al., 2002) (Box 5-2).

Potential Impact of Nicotine Replacement Therapy

The provision of NRT with an effectiveness of 1 percent is predicted to result in the avoidance of about 3.5 million smoking-attributable deaths (Table 5-3). NRT of 5 percent effectiveness will have about five times the impact. Again, LMCs would account for roughly 80 percent of the averted deaths. The relative impact of NRT (of 2.5 percent effectiveness) on deaths averted is 2 to 3 percent among individuals ages 15 to 59, and lower among those ages 60 and older (results not shown). Clearly, NRT is more expensive than interventions such as tax increases, and will not be affordable everywhere, despite being relatively cost effective.

Potential Impact of Nonprice Interventions Other Than NRT

A package of nonprice interventions other than NRT that decrease the prevalence of smoking by 2 percent is predicted to prevent about 7 million smoking-attributable deaths (more than 1.6 percent of all smoking-attributable deaths among those who smoked in 2000; see Table 5-4). A package of interventions that decreases the prevalence of smoking by 10

TABLE 5-2 Potential Impact of Price Increases of 10 Percent, 33 Percent, 50 Percent, and 70 Percent on Tobacco Mortality by World Bank Region, 2000

|

|

Smoking attributable deaths in millions |

Change in number of deaths in millions |

|||||||

|

|

10% price increase |

33% price increase |

50% price increase |

70% price increase |

|||||

|

World Bank Region |

Low |

High |

Low |

High |

Low |

High |

Low |

High |

|

|

East Asia and Pacific (percent) |

173 |

–2.9 (–1.7) |

–8.7 (–5.0) |

–9.6 (–5.5) |

–27.5 (–15.9) |

–14.5 (–8.4) |

–37.5 (–21.7) |

–20.3 (–11.7) |

–46.2 (–26.8) |

|

Europe and Central Asia (percent) |

51 |

–0.9 (–1.7) |

–2.6 (–5.1) |

–2.8 (–5.6) |

–8.1 (–16.0) |

–4.3 (–8.5) |

–11.2 (–22.0) |

–6.0 (–11.8) |

–13.8 (–27.2) |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean (percent) |

40 |

–0.7 (–1.8) |

–2.1 (–5.3) |

–2.3 (–5.8) |

–6.7 (–16.8) |

–3.5 (–8.8) |

–9.5 (–23.7) |

–4.9 (–12.3) |

–11.6 (–29.1) |

|

Middle East and North Africa (percent) |

13 |

–0.2 (–1.7) |

–0.7 (–5.2) |

–0.8 (–5.8) |

–2.2 (–16.6) |

–1.2 (–8.7) |

–3.1 (–23.2) |

–1.6 (–12.2) |

–3.8 (–28.5) |

|

South Asia (percent) |

62 |

–0.9 (–2.4) |

–2.6 (–8.6) |

–2.9 (–9.5) |

–8.5 (–27.7) |

–4.4 (–14.3) |

–12.5 (–40.6) |

–6.2 (–20.1) |

–16 (–52) |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa (percent) |

23 |

–0.4 (–1.6) |

–1.1 (–4.9) |

–1.3 (–5.4) |

–3.7 (–15.9) |

–1.9 (–8.2) |

–5.5 (–23.6) |

–2.7 (–11.5) |

–6.6 (–28.5) |

|

Low- and middle-income (percent) |

362 |

–6.0 (–1.6) |

–17.9 (–4.9) |

–19.7 (–5.4) |

–56.8 (–15.7) |

–29.8 (–8.2) |

–79.2 (–21.9) |

–41.7 (–11.5) |

–98.2 (–27.1) |

|

High-income (percent) |

81 |

–0.6 (–0.8) |

–2.6 (–3.2) |

–2.1 (–2.6) |

–8.5 (–10.6) |

–3.2 (–4.0) |

–12.2 (–15.1) |

–4.5 (–5.6) |

–16.2 (–20.0) |

|

World (percent) |

443 |

–6.6 (–1.5) |

–20.5 (–4.6) |

–21.8 (–4.9) |

–65.3 (–14.7) |

–33.0 (–7.5) |

–91.5 (–20.7) |

–46.2 (–10.4) |

–114.3 (–25.8) |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Jha et al. (2006). Copyright 2006 by the World Bank. |

|||||||||

|

BOX 5-2 Tobacco Control in Poland Through the 1980s Poland had among the highest smoking rates in the world and higher lung cancer rates than any other country in Europe, save Hungary. Nearly three-quarters of men and 30 percent of women were regular smokers. An estimated 42 percent of cardiovascular deaths and 71 percent of deaths from respiratory diseases among middle-aged men were caused by smoking. Members of the Polish public were ill informed about the hazards of smoking, so few perceived a reason to stop. Cigarettes in Poland were produced by a government-run enterprise and were a significant source of revenue, particularly important in lean economic times. The fall of communism in Poland led to increases in smoking, not only among adults, but among adolescents and teenagers. By the mid-1990s, the tobacco industry was almost completely in private hands, with multinational tobacco corporations playing an ever larger role. Prices were kept low as a result of agreements between the government and the tobacco companies. Cigarettes became the most heavily advertised product in the country, as companies vied for market share and a bigger smoker population, with a goal of increasing cigarette consumption by 10 percent per year. The success of these efforts was seen in increased smoking rates, particularly among adolescents and young teens (Zatonski, 1998). The Tobacco Control Movement Anti-tobacco forces began to organize during the 1980s as part of the first initiatives of Poland’s emerging civil society. The Polish Anti-Tobacco Society and other groups formed and began to reach out domestically and internationally. The Polish mass media were increasingly active in reporting on health issues, including the dangers of tobacco. In the 1990s, when Polish society opened up, the movement took hold. A conference called “A Tobacco-Free New Europe,” with health advocates from Eastern and Western Europe, was held in Kazimierz, Poland, in 1990. The policy recommendations that emerged from that meeting became the basis for legislation proposed to the Polish Senate beginning in 1991. Several years of intense, heavily funded opposition by the tobacco industry and public debate ensued. Public opinion eventually swung toward the health advocates, and in 1995 the Senate passed—with 90 percent of the vote—the “Law for the Protection of Public Health Against the Effects of Tobacco Use.” Provisions included a ban on smoking and cigarette sales in health care centers, schools, and enclosed workplaces; a ban on tobacco sales to those under 18 years; a ban on smokeless tobacco; a ban on radio and television advertising and limits on other media; large health warnings on cigarette packages; and free smoking |

|

cessation treatment. Later measures raised taxes on cigarettes by 30 percent each year in 1999 and 2000. The Health Promotion Foundation led the legislative effort, accompanied by public education and action campaigns, including annual “smokeouts” credited with helping 2.5 million smokers to quit over a decade. The Results During the 1990s, cigarette consumption fell 10 percent, smoking among adult men fell from 62 to 40 percent, and among adult women, from 30 to 20 percent. The health benefits were almost immediate: overall mortality fell by 10 percent over the same period, and about one-third of the decline is attributed to smoking reductions. Lung cancer rates also had begun to decrease, falling 30 percent in younger men (ages 20–44) and 19 percent in men ages 45–64. Positive effects on cardiovascular disease and low-birthweight babies is also attributable to the decline in smoking. Poland and its neighbor Hungary had similar lung cancer rates in the 1980s, but Hungary did not take measures to control tobacco when Poland did. While lung cancer rates fell in Poland, they continued to rise through the 1990s in Hungary, and are now substantially higher. SOURCE: Levine and Kinder (2004). |

percent would have an impact five times greater. LMCs would account for approximately four-fifths of quitters and averted deaths. The greatest relative impact of nonprice interventions on deaths averted would be among younger age cohorts.

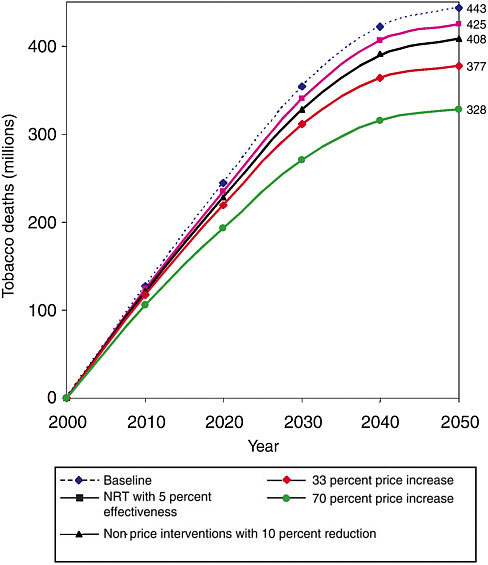

Figure 5-4 summarizes the potential impact of a set of independent tobacco control interventions, using 33 percent and 70 percent price increases (employing a high elasticity of –1.2 for low- and middle-income regions and –0.8 for high-income regions), a 5 percent effectiveness of NRT, and a 10 percent reduction from nonprice interventions other than NRT. In this cohort of smokers alive in 2000, approximately 443 million are expected to die in the next 50 years in the absence of interventions. A substantial fraction of these tobacco deaths are avoidable with interventions. Price increases have the greatest impact on tobacco mortality, with the most aggressive price increase of 70 percent having the potential to avert nearly one-quarter of all tobacco deaths. Even a modest price increase of 33 percent could potentially prevent 66 million tobacco deaths over the course of the next 50 years. While NRTs and other nonprice interventions are less effective than price increases, they can still avert a substantial number of tobacco deaths (18 million and 35 million deaths, respectively). The greatest impact of these

TABLE 5-3 Potential Impact of Price Increase of 33 Percent, Increased NRT Use, and a Package of Nonprice Measures, 2000

|

|

|

Change in number of deaths in millions |

|||||

|

|

Smoking attributable deaths in millions |

33% price increase |

NRT effectiveness |

Nonprice intervention effectiveness |

|||

|

World Bank Region |

Low elasticity |

High elasticity |

1.0% |

5.0% |

2% |

10% |

|

|

East Asia and Pacific (percent) |

173 |

–9.6 (–5.5) |

–27.5 (–15.9) |

–1.4 (–0.8) |

–6.9 (–4.0) |

–2.8 (–1.6) |

–13.8 (–8.0) |

|

Europe and Central Asia (percent) |

51 |

–2.8 (–5.6) |

–8.1 (–16.0) |

–0.4 (–0.8) |

–2.1 (–4.0) |

–0.8 (–1.6) |

–4.1 (–8.1) |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean (percent) |

40 |

–2.3 (–5.8) |

–6.7 (–16.8) |

–0.3 (–0.8) |

–1.7 (–4.2) |

–0.7 (–1.7) |

–3.4 (–8.5) |

|

Middle East and North Africa (percent) |

13 |

–0.8 (–5.8) |

–2.2 (–16.6) |

–0.11 (–0.8) |

–0.6 (–4.2) |

–0.2 (–1.7) |

–1.1 (–8.4) |

|

South Asia (percent) |

62 |

–2.9 (–9.5) |

–8.5 (–27.7) |

–0.4 (–1.4) |

–2.2 (–7.2) |

–0.9 (–2.8) |

–4.3 (–13.9) |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa (percent) |

23 |

–1.3 (–5.4) |

–3.7 (–15.9) |

–0.2 (–0.8) |

–0.9 (–4.0) |

–0.4 (–1.6) |

–1.8 (–7.9) |

|

Low- and middle-income (percent) |

362 |

–19.7 (–5.4) |

–56.8 (–15.7) |

–2.9 (–0.8) |

–14.3 (–4.0) |

–5.7 (–1.6) |

–28.6 (–7.9) |

|

High-income (percent) |

81 |

–2.1 (–2.6) |

–8.5 (–10.6) |

–0.6 (–0.8) |

–3.1 (–3.8) |

–1.2 (–1.5) |

–6.1 (–7.6) |

|

World (percent) |

443 |

–21.8 (–4.9) |

–65.3 (–14.8) |

–3.5 (–0.8) |

–17.4 (–3.9) |

–6.9 (–1.6) |

–34.7 (–7.8) |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Jha et al. (2006). Copyright 2006 by the World Bank. |

|||||||

tobacco control interventions would occur after 2010, but a substantial number of deaths could be avoided even before then.

No attempt has been made in this analysis to examine the impact of combining the various packages of interventions (e.g., price increases with NRT, or NRT and other nonprice interventions). A number of studies have compared the impact of price and nonprice interventions, but few empirical attempts have been made to assess how these interventions might interact. While price increases may be the most cost-effective antismoking intervention, policy makers should use all the tools at their disposal to counter smoking. Nonprice measures may be required to reach the most heavily dependent smokers, for whom medical and social support in stopping will

TABLE 5-4 Range of Cost-Effectiveness Values for Price Increase, Nicotine Replacement Therapies, and Nonprice Interventions (2002 US dollars per DALY Saved), by World Bank Region, 2000

|

|

Smoking attributable deaths in millions |

33% price increase |

NRTs with effectiveness of 1% to 5% |

Nonprice interventions with effectiveness of 2% to 10% |

|||

|

World Bank Region |

Low-end estimate |

High-end estimate |

Low-end estimate |

High-end estimate |

Low-end estimate |

High-end estimate |

|

|

East Asia and Pacific |

173 |

2 |

30 |

65 |

864 |

40 |

498 |

|

Europe and Central Asia |

51 |

3 |

42 |

45 |

633 |

55 |

685 |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

40 |

6 |

85 |

53 |

812 |

109 |

1,361 |

|

Middle East and North Africa |

13 |

6 |

89 |

47 |

750 |

115 |

1,432 |

|

South Asia |

62 |

2 |

27 |

54 |

716 |

34 |

431 |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

23 |

2 |

26 |

42 |

570 |

33 |

417 |

|

Low- and middle-income |

362 |

3 |

42 |

55 |

761 |

54 |

674 |

|

High-income |

81 |

85 |

1,773 |

175 |

3,781 |

1,166 |

14,572 |

|

World |

443 |

13 |

195 |

75 |

1,250 |

233 |

2,916 |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Jha et al. (2006). Copyright 2006 by the World Bank. |

|||||||

be necessary. Furthermore, these nonprice measures may be effective in increasing social acceptance and support of tobacco price increases.

Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs

In recent years, several governments, mostly in high-income countries, have adopted comprehensive programs to reduce tobacco use, often funded by earmarked tobacco tax revenues. These programs have similar goals for reducing tobacco use, including preventing initiation among youth and young adults, promoting cessation among all smokers, reducing exposure to passive tobacco smoke, and identifying and eliminating disparities among population subgroups (U.S. DHHS, 1994). These programs have one or more of four key components: (1) community interventions engag-

FIGURE 5-4 Potential impact of tax increases, nicotine reduction therapies, and nonprice interventions on tobacco mortality, 2000–2050, among the world’s smokers in 2000.

NOTE: Price increases assume a high price elasticity (–1.2 for low- and middle-income countries and –0.8 for high-income countries).

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Jha et al. (2006). Copyright 2006 by the World Bank.

ing a diverse set of local organizations; (2) countermarketing and health information campaigns; (3) program policies and regulations (e.g., taxes, restrictions on smoking, bans on tobacco advertising, and access to better cessation treatments); and (4) surveillance and evaluation of potential issues, such as smuggling (U.S. DHHS, 1994). Programs have placed differing emphasis on these four components, with substantial diversity among the types of activities supported within each component. Recent analyses from the United States and United Kingdom clearly indicate that these comprehensive efforts have been successful in reducing tobacco use and in improving public health (Farrelly et al., 2003; Townsend et al., 1994; U.S. DHHS, 1994). In California, for example, the state’s comprehensive tobacco control program has produced a rate of decline in tobacco use double that seen in the rest of the United States. As with other aspects of tobacco control, the impacts of comprehensive tobacco control may be different in LMCs than they are in high-income countries, which differ in much more than simply economic status. The following discussion is presented with the understanding that efforts to develop comprehensive tobacco control in LMCs should be accompanied by adequate monitoring and evaluation to ensure that the efforts are worthwhile.

The cost of implementing control programs is relatively low and certainly affordable for high-income countries. Table 5-5 provides the estimated total costs of implementing price and NRT interventions by World Bank region. Current estimates of the costs of implementing a comprehensive tobacco control program range from $2.50 to $10 per capita in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends spending $6 to $16 per capita for a comprehensive tobacco control program in the United States (CDC, 1999). Canadian spending on tobacco control programs was approximately $1.65 per capita in 1996 (Pechmann et al., 1998). At the highest recommending spending level ($16 per capita) in the United States, annual funding for a comprehensive tobacco program would equal 0.9 percent of U.S. public spending, per capita, on health.

Constraints to Effective Tobacco Control Policies

Use of the effective interventions described here is uneven and limited (see a more formal analysis in Chaloupka et al., 2001). World Bank data reveal that there is ample room to increase tobacco taxes: In 1995 the average percentage of all government revenue derived from tobacco tax was 0.63. Middle-income countries averaged 0.51 percent of government revenue from tobacco taxes, while lower income countries averaged 0.42 percent. An increase in cigarette taxes of 10 percent globally would raise cigarette tax revenues by nearly 7 percent, with relatively larger increases in revenues in high-income countries, and smaller increases in revenues in LMCs (Sunley

TABLE 5-5 Estimated Cost of Price Intervention and Nicotine Replacement Therapy Programs by World Bank Region

|

|

|

Cost for price increase (millions 2002 US$) |

Cost of NRTs ($25 to $150) (millions 2002 US$) |

||||||

|

|

GDP (billions 2002 US$ ) |

Low-end estimate |

High-end estimate |

To treat 1% of current smokers |

To treat 5% of current smokers |

||||

|

World Bank Region |

$25 |

$50 |

$150 |

$25 |

$50 |

$150 |

|||

|

East Asia and Pacific |

1,802 |

360 |

901 |

1,079 |

2,158 |

6,474 |

5,395 |

10,791 |

32,372 |

|

Europe and Central Asia |

1,136 |

227 |

568 |

318 |

635 |

1,906 |

1,588 |

3,176 |

9,529 |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

1,673 |

335 |

836 |

250 |

500 |

1,500 |

1,250 |

2,500 |

7,499 |

|

Middle East and North Africa |

694 |

139 |

347 |

84 |

169 |

506 |

422 |

843 |

2,530 |

|

South Asia |

655 |

131 |

327 |

2,312 |

1,926 |

3,853 |

11,558 |

2,312 |

1,926 |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

319 |

64 |

159 |

868 |

723 |

1,447 |

4,340 |

868 |

723 |

|

Low- and middle-income |

6,256 |

1,251 |

3,128 |

13,565 |

11,305 |

22,609 |

67,827 |

13,565 |

11,305 |

|

High-income |

25,992 |

5,198 |

12,996 |

3,034 |

2,529 |

10,114 |

15,172 |

3,034 |

2,529 |

|

World |

32,253 |

6,451 |

16,126 |

16,600 |

13,833 |

32,723 |

82,999 |

16,600 |

13,833 |

|

GDP = Gross domestic product. SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Jha et al. (2006). Copyright 2006 by the World Bank. |

|||||||||

et al., 2000). Despite this, price increases have been underused. Guindon and colleagues (2002) studied 80 countries and found that the real price of tobacco, adjusted for purchasing power, fell in most developing countries from 1990 to 2000.

Why is there so much variation in tobacco control policies? The political economy of tobacco control has been inadequately studied. A few plausible areas of interest are outlined here. First, the recognition of tobacco as a major health hazard appears to be the impetus for most of the tobacco control policies in many high-income countries. There is some evidence that improved national capacity and local needs assessment could increase the likelihood that tobacco control measures will be adopted. For example, econometric analyses in South Africa geared to local policy needs substantially increased the willingness of the country to implement tobacco control policies (Abedian et al., 1998). Second, tobacco control budgets are only a fraction of what is required. Funding is needed not so much to implement programs, but to counter tobacco industry tactics and to build popular support for control. Third, the most obvious constraint to tobacco control is political opposition, but this is difficult to quantify. Opposition from the tobacco industry is well organized and well funded (Pollock, 1996).

A key political tool for addressing political opposition is earmarking tobacco taxes. Earmarking has been successful in several countries, including Australia, Finland, Nepal, and Thailand. Of the 48 countries currently in the WHO European Region, 12 earmark taxes for tobacco control and other public health measures. The average level of allocation is less than 1 percent of total tax revenue (WHO, 2002). Earmarking does introduce clear restrictions and inefficiencies on public finance, and for this reason alone most macroeconomists do not favor earmarking, no matter how worthy the cause. However, earmarking tobacco taxes can be justified if governments use these funds to benefit those who pay for tobacco control policies and programs, and secure public support for new or higher tobacco taxes.

Earmarked taxes also have a political function in that they help to concentrate political winners of tobacco control, and thus influence policy. Earmarked funds that support broad health and social services (e.g., other disease programs) broaden the political and civil society support base for tobacco control. In Australia, broad political support among the Ministries of Sports and Education helped to convince the Ministry of Finance that raising tobacco taxes was possible. Indeed, once an earmarked tax was passed, the Ministry of Finance went on to raise tobacco taxes further without earmarking (Galbally, 1997). Additionally, targeting revenue from tobacco taxes to other health programs for the poorest socioeconomic groups could produce double health gains—reduced tobacco consumption combined with increased access to and use of health services. In China, a 10 percent increase in cigarette taxes would decrease consumption by 5 percent and increase

government revenue by 5 percent. These increased earnings could finance a package of essential health services for one-third of China’s poorest 100 million citizens in 1990 (Saxenian and McGreevey, 1996).

Monitoring the Effects of Tobacco (and Other Important Risk Factors)

Understanding trends in the use of tobacco and its consequences is important to understanding population health generally, and to determining how well interventions are working to reduce tobacco use. It is possible to do this through economical long-term studies of large samples of the population. Such prospective studies (described in Chapter 3) should be considered an integral part of cancer (and other chronic disease) control.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

There is no real disagreement about the health effects of tobacco: At least half of all long-term smokers eventually die from tobacco-related disease, including, but not limited to, cancer. Also incontrovertible, but not as well appreciated, is that stopping smoking reduces the risk of tobacco-related death enormously. The question is how to get current smokers to stop (most important) and how to discourage nonsmokers (young people and adults) from taking up smoking. A relatively large body of evidence, most from high-income countries, supports both “demand-” and, to a lesser extent, “supply-” side interventions. These are the interventions that are included in the FCTC, and endorsed by this report. The most important step is ratification of the FCTC by as many countries as possible, at which time they will be obligated to adopt its provisions.

RECOMMENDATION 5-1. Every country should sign and ratify the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and implement its provisions, most importantly:

-

Substantial increases in taxation to raise the prices of tobacco products (goal is to have taxes at 80 percent or higher of retail price)

-

Complete advertising and promotion bans on tobacco products

-

Mandating that public spaces be smoke free

-

Large, explicit cigarette packet warnings in local languages (which also helps to reduce smuggling)

-

Support of counteradvertising to publicize the health damage from tobacco and the benefits of stopping tobacco use

REFERENCES

Abedian I, van der Merwe R, Wilkins N, Jha P. 1998. The Economics of Tobacco Control: Towards an Optimal Policy Mix. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs. Atlanta: GA: Department of Health and Human Services.

Chaloupka FJ, Hu TH, Warner KE, Jacobs R, Yurekli A. 2000. The taxation of tobacco products. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Pp. 238–272.

Chaloupka FJ, Jha P, Corrao MA, Costa e Silva V, Ross H, Czart C, Yach D. 2001. The Evidence Base for Reducing Mortality From Smoking in Low and Middle Income Countries. Commission on Macroeconomics and Health Working Paper Series. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Chinese Academy of Preventive Medicine. 1997. Smoking in China: 1996 National Prevalence Survey of Smoking Pattern. Beijing, China: China Science and Technology Press.

Crispo A, Brennan P, Jockel KH, Schaffrath-Rosario A, Wichmann HE, Nyberg F, Simonato L, Merletti F, Forastiere F, Boffetta P, Darby S. 2004. The cumulative risk of lung cancer among current, ex- and never-smokers in European men. British Journal of Cancer 91(7):1280–1286.

Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. 2004. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. British Medical Journal 328(7455):1519–1528.

Emery S, White MM, Pierce JP. 2001. Does cigarette price influence adolescent experimentation? Journal of Health Economics 20(2):261–270.

Ezzati M, Lopez AD. 2003. Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. Lancet 362(9387):847–852.

Farrelly MC, Pechacek TF, Chaloupka FJ. 2003. The impact of tobacco control program expenditures on aggregate cigarette sales: 1981–2000. Journal of Health Economics 22(5):843–859.

Federal Trade Commission. 2003. Cigarette Report for 2001. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission.

Gajalakshmi CK, Jha P, Ranson K, Nguyen S. 2000. Global patterns of smoking and smoking attributable mortality. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Pp. 11–39.

Gajalakshmi V, Peto R, Kanaka TS, Jha P. 2003. Smoking and mortality from tuberculosis and other diseases in India: Retrospective study of 43,000 adult male deaths and 35,000 controls. Lancet 362(9383):507–515.

Galbally RL. 1997. Health-promoting environments: Who will miss out? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 21(4 Spec. No.):429–430.

Gallus S, Schiaffino A, La Vecchia C, Townsend J, Fernandez E. 2006. Price and cigarette consumption in Europe. Tobacco Control 15(2):114–119.

Goldberg ME. 2003. Correlation, causation, and smoking initiation among youths. Journal of Advertising Research 43(1):431–440.

Gruber J. 2003. Government Policy Toward Smoking: A New View From Economics. Paper presented at the Disease Control Priorities Project Nicotine Addiction Workshop, Mumbai, India. DCPP Working Paper Series.

Guindon GE, Tobin S, Yach D. 2002. Trends and affordability of cigarette prices: Ample room for tax increases and related health gains. Tobacco Control 11(1):35–43.

Hamzah E. 2005. Malaysian Case Study of Cancer Control. Unpublished.

Hu TW, Xu X, Keeler T. 1998. Earmarked tobacco taxes: Lessons learned. In: Abedian I, van der Merwe R, Wilkins N, Jha P. The Economics of Tobacco Control. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town, Applied Fiscal Research Centre.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection. Curry, SJ, Byers, T, Hewitt, M, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jacobs R, Gale HF, Capehart TC, Zhang P, Jha P. 2000. The supply-side effects of tobacco control policies. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Pp. 312–341.

Jha P, Chaloupka F. 2000a. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Jha P, Chaloupka FJ. 2000b. The economics of global tobacco control. BMJ 321(7257): 358–361.

Jha P, Chaloupka FJ. 1999. Curbing the Epidemic: Governments and the Economics of Tobacco Control. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, Moore J, Gajalakshmi V, Gupta PC, Peck R, Asma S, Zatonski W. 2006. Tobacco addiction. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, eds. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jha P, Musgrove P, Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A.2000. The economic rationale for intervention in the tobacco market. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Pp. 154–174.

Joossens L, Chaloupka FJ, Merriman D, Yurekli A. 2000. Issues in the smuggling of tobacco products. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Pp. 394–406.

Kaper J, Wagena EJ, Severens JL, Van Schayck CP. 2005. Healthcare financing systems for increasing the use of tobacco dependence treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1):CD004305.

Kenkel D, Chen L. 2000. Consumer information and tobacco use. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Pp. 154–174.

Lam TH, He Y, Shi QL, Huang JY, Zhang F, Wan ZH, Sun CS, Li LS. 2002. Smoking, quitting, and mortality in a Chinese cohort of retired men. Annals of Epidemiology 12(5):316–320.

Lance PM, Akin JS, Dow WH, Loh CP. 2004. Is cigarette smoking in poorer nations highly sensitive to price? Evidence from Russia and China. Journal of Health Economics 23(1):173–189.

Levine R, Kinder M. 2004. Millions Saved: Proven Successes in Global Health. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Levy DT, Friend K, Polishchuk E. 2001. Effect of clean indoor air laws on smokers: The clean air module of the SimSmoke computer simulation model. Tobacco Control 10(4):345–351.

Lightwood J, Collins D, Lapsley H, Novotny TE. 2000. Estimating the costs of tobacco use. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Pp. 63–103.

Liu BQ, Peto R, Chen ZM, Boreham J, Wu YP, Li JY, Campbell TC, Chen JS. 1998. Emerging tobacco hazards in China: Retrospective proportional mortality study of one million deaths. BMJ 317(7170):1411–1422.

Merriman D, Yurekli A, Chaloupka FJ. 2000. How big is the worldwide cigarette smuggling problem? In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Molarius A, Parsons RW, Dobson AJ, Evans A, Fortmann SP, Jamrozik K, Kuulasmaa K, Moltchanov V, Sans S, Tuomilehto J, Puska P, WHO MONICA Project. 2001. Trends in cigarette smoking in 36 populations from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s: Findings from the WHO MONICA Project. American Journal of Public Health 91(2):206–212.

Niu SR, Yang GH, Chen ZM, Wang JL, Wang GH, He XZ, Schoepff H, Boreham J, Pan HC, Peto R. 1998. Emerging tobacco hazards in China: Early mortality results from a prospective study. BMJ 317(7170):1423–1424.

Novotny TE, Cohen JC, Yurekli A, Sweaner D, de Beyer J. 2000. Smoking cessation and nicotine-replacement therapies. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Pechmann C, Dixon P, Layne N. 1998. An assessment of U.S. and Canadian smoking reduction objectives for the year 2000. American Journal of Public Health 88(9):1362–1367.

Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. 2000. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: Combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. BMJ 321(7257):323–329.

Peto R, Lopez A, Boreham J, Thun M. 1994. Mortality from Smoking in Developed Countries, 1950–2000. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Peto R, Lopez A, Boreham J, Thun M. 2003. Mortality from Smoking in Developed Countries. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Peto R, Lopez AD. 2002. Future worldwide health effects of current smoking patterns. In: Koop EC, Pearson CE, Schwarz MR, eds. Critical Issues in Global Health. New York: Jossey-Bass.

Pollock D. 1996. Forty years on: A war to recognise and win. How the tobacco industry has survived the revelations on smoking and health. British Medical Bulletin 52(1):174–182.

Ranson MK, Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, Nguyen SN. 2002. Global and regional estimates of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of price increases and other tobacco control policies. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 4(3):311–319.

Raw M, McNeill A, West R. 1999. Smoking cessation: Evidence based recommendations for the healthcare system. BMJ 318(7177):182–185.

Ross H, Chaloupka FJ, Wakefield M. 2001. Youth Smoking Uptake Progress: Price and Public Policy Effects. Research Paper No. 11. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois at Chicago, Health Research and Policy Centers, ImpacTeen.

Saffer H. 2000. Tobacco advertising and promotion. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Saffer H, Chaloupka F. 2000. The effect of tobacco advertising bans on tobacco consumption. Journal of Health Economics 19(6):1117–1137.

Saxenian H, McGreevey B. 1996. China: Issues and Options in Health Financing. World Bank Report No. 15278-CHA. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Sloan FA, Ostermann J, Conover C, Taylor DH Jr., Picone G. 2004. The Price of Smoking. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sunley EM, Yurekli A, Chaloupka FJ. 2000. The design, administration, and potential revenue of tobacco excises. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Pp. 410–426.

Tauras JA. 1999. The Transition to Smoking Cessation: Evidence From Multiple Failure Duration Analysis. NBER Working Paper No. 7412. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Tauras JA, Chaloupka FJ. 2003. The demand for nicotine replacement therapies. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 5(2):237–243.

Tauras JA, Chaloupka FJ, Farrelly MC, Giovino GA, Wakefield M, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Kloska DD, Pechacek TF. 2005. State tobacco control spending and youth smoking. American Journal of Public Health 95(2):338–344.

Taylor CR, and Bonner PG. 2003. Comment on “American media and the smoking-related behavior of Asian adolescents.” Journal of Advertising Research 43:419–430.

Taylor A, Chaloupka FJ, Guindon E, Corbett M. 2000. The impact of trade liberalization on tobacco consumption. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Pp. 344–364.

Townsend J. 1993. Policies to halve smoking deaths. Addiction 88(1):37–46.

Townsend J, Roderick P, Cooper J. 1994. Cigarette smoking by socioeconomic group, sex, and age: Effects of price, income, and health publicity. BMJ 309(6959):923–927.

UK Department of Health. 1992. Effect of Tobacco Advertising on Tobacco Consumption: A Discussion Document Reviewing the Evidence. London, England: UK Department of Health, Economics and Operational Research Division.

U.S. DHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 1994. Preventing Tobacco Use Amongst Young People. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

U.S. DHHS. 2000. Reducing Tobacco Use. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Wasserman J, Manning WG, Newhouse JP, Winkler JD. 1991. The effects of excise taxes and regulations on cigarette smoking. Journal of Health Economics 10(1):43–64.

Weinstein ND. 1998. Accuracy of smokers’ risk perceptions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 20(2):135–140.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2002. The European Report on Tobacco Control Policy. WHO European Ministerial Conference for a Tobacco-Free Europe. Warsaw, Poland. Document EUR/01/5020906/8. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

WHO. 2003. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. [Online] Available: http://www. who.int/tobacco/framework/WHO_FCTC_english.pdf [accessed 1/2/06].