7

Palliative Care

When people develop cancer, whether they are rich or poor, whether they live in a rich or poor country, and whether they have access to the best that curative medicine can offer or no access, a large proportion will suffer pain and other distressing physical and psychological symptoms. These symptoms worsen as cancer advances and death approaches. Because cancers in low- and middle-income countries (LMCs) are much more likely to go undetected until late stages and curative treatment may not be available even for early stage cancers, an even greater proportion of patients will likely experience severe symptoms than in high-income countries. The appropriate response for all such patients is palliative care to relieve pain and other symptoms and care for the person, whether he or she is on the road to recovery, has completed treatment, or is near the end of life.

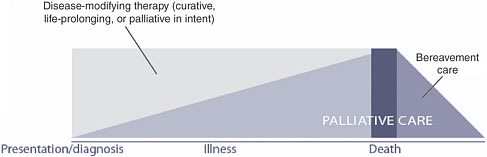

The World Health Organization (WHO) definition of palliative care (Box 7-1) is comprehensive and embodies an ideal situation. Treatment of cancer and palliative care are complementary activities. Figure 7-1 illustrates the shift over time from life-prolonging treatment to palliative care. The shift signifies not only a change in the type of treatment, but a change in the intensity of treatment as the end of life nears.

The availability of primary cancer treatment and the cancer infrastructure are extremely variable in LMCs. In many low-income countries treatment may be almost nonexistent for the large majority. To the extent that cancer care is available, and particularly where governments are developing and implementing programs, they should, of course, include palliative care as an essential component. But palliative care is possible even where little

|

BOX 7-1 The World Health Organization Definition of Palliative Care Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual. Palliative care:

SOURCE: WHO (2002). |

else for cancer exists. It can become the organizing principle for expanding cancer services. In either case, some official recognition of the need for and the requirements of palliative care are almost certain to be essential for progress. Ideally, medical, nursing, and social work students (and other relevant health care workers) will receive training in palliative care and practitioners will incorporate palliative care into routine practice. The starting point in each country for each of these aspects is likely to be somewhat different, depending on existing services and circumstances.

The starting point for this chapter is an overview of palliative care in Africa, the continent with the least developed programs. Because pain control is so central to palliative care, much of the remainder of the chapter is devoted to understanding the role of pain control in palliative care for

FIGURE 7-1 The need for palliative care throughout the course of serious illness.

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from WHO (2002). Copyright 2002 by WHO.

cancer, and to ways in which pain control can be expanded to form the core of expanded palliative care, which is taken up at the end of the chapter.

STATUS OF PALLIATIVE CARE IN AFRICA

The earliest developments in palliative care began about 25 years ago. Given the poverty, political turmoil, and myriad other challenges the African continent has had to face, it would be surprising if much effort had gone toward easing the suffering of those dying from cancer and other diseases. Progress has been slow and only a small fraction of those experiencing pain or other symptoms today receive palliative care. The general picture of a few hospices (organized services specifically for people approaching death in a matter of no more than months) and other foci of palliative care (e.g., places that provide care for symptoms at any time of illness, up to and including the end of life), and the more widespread absence of such care, has been generally acknowledged, but little detail has been attached to it. A recent survey by the Observatory on End-of-Life Care provides the first systematic look at palliative care in a large number of African countries.

Observatory on End-of-Life Care: Africa Assessment

During 2004–2005, representatives from the International Observatory on End-of-Life Care (“the Observatory”) traveled around Africa meeting with contacts knowledgeable about palliative care (Personal communication, D. Clark, Director, International Observatory on End-of-Life Care, 2005). After surveying 47 countries, they developed a typology of 3 categories that captures the state of palliative care development in each country.

-

Capacity-building stage: no services operating yet, but evidence of individuals attending training programs or conferences; oral morphine largely unavailable.

-

Localized service provision: isolated palliative care and hospice services available in local areas; often heavily dependent on outside donors; no significant impact on broader national policy; oral morphine availability extremely limited.

-

Approaching integration: national recognition of the importance of palliative care (e.g., in policy documents); training readily available; reimbursement scheme for hospice/palliative care services in place; greater availability of morphine.

Of the 47 countries assessed, palliative care had no appreciable presence in 21 counties, 11 were at the “capacity-building” stage, 11 were at the stage of “localized service provision,” and 4 were “approaching integration.” The latter four are South Africa, Zimbabwe, Kenya, and Uganda (the most advanced, described below). The history of how services developed in each of these four is quite different, but each involves one or a few leaders without whom progress would not have occurred.

Countries may remain in stage 1 or 2 or they may progress. In countries where the situation remains unchanged for years, new or renewed leadership from within or assistance from the outside may be needed to generate movement. Progress can stop or be lost if the leaders have not been able to make headway, and this can lead to burnout and disillusionment.

The typology may be applicable outside of Africa, particularly in parts of the world where many countries are developing palliative care capacity. The Observatory will be assessing palliative care in the countries of Eastern and Central Europe and the Central Asian republics in the coming years, using this framework.

Palliative Care in Uganda: Hospice Uganda

Uganda has the most advanced hospice program in Africa that provides palliative care to patients nearing the end of life. Hospice Uganda began work out of a Kampala hospital with an old Land Rover, a grant to last 3 months, and a mandate to become the model home-based hospice for Africa for dying cancer and AIDS patients. It was started by Anne Merriman, a transplanted Irish palliative care specialist who had spent much of her career in Africa and Asia. Her experience at the Nairobi Hospice in Kenya—in 1990, only the third hospice in Africa—taught her that when trying to export the western hospice model to another continent, she needed ways that met the needs of poor Africans in their homes.

After systematically considering a number of countries interested in

hosting the model project, Uganda was selected by the parent organization, Hospice Africa. The project has expanded from the original Kampala location, which has served about 4,000 patients living within 20 km of Kampala, to two rural sites. Mobile Hospice Mbarara commenced service in January 1998, using a similar model to the Kampala service. Little Hospice Hoima began one month later as a demonstration of an affordable service to reach the village level, and has treated a few hundred rural patients.

Hospice Uganda reaches farther than the three hospice programs. From the beginning, the aim was to train people from around the country to provide this care. As of February 2003, in Kampala, 20 courses to certify health professionals and 11 courses to certify volunteers had been held. More courses have been given in Mbarara, Hoima, and other districts. In total, nearly 1,000 professionals and 500 nonprofessionals have been trained. As a result, palliative care is being extended throughout the country.

In 1998, an advisory team to the Ministry of Health was formed, resulting in Uganda being the first government in Africa to list palliative care as an essential clinical service incorporated into a 5-year health plan (for 2000–2005). At this time, a senior physician and Chairman of the National Drug Authority was appointed as a senior advisor to Hospice Uganda. In 2000, the advisory team was replaced by a Palliative Care Country Team, which includes all the stakeholders, including the government, funders, and educators, as well as Hospice Uganda.

A barrier to pain relief in rural areas, in particular, was the legal requirement common to many countries that morphine be prescribed by a physician. This effectively barred most of the population from ever having access to effective pain control. Dr. Merriman insisted that oral morphine be available before starting palliative care. The government was persuaded to change the statute governing the prescribing of morphine. Guidelines were published by the Ministry of Health in 2001 to allow specialist palliative care nurses and clinical officers—trained and registered in Uganda—to prescribe morphine. Even the rural police are now aware that nurse practitioners carry morphine. Before Hospice Uganda arrived, these drugs were unavailable in the country.

Another requirement—that the diagnosis of terminal cancer or AIDS be made by a doctor—is recognized as a barrier because most people never see a doctor. In villages, the palliative care team will have to diagnose and treat without referrals, which requires training tailored to the particular area, but likely without much medical technology. As a result of these efforts, morphine is now available, paid for by the government, in about 15 of the 56 districts in the country.

The cost of treatment in Kampala and Mbarara is about $7 per week, including one home visit. About one-third of the cost is for medications (mainly liquid morphine, which is mixed locally, making it relatively inex-

pensive). If patients can come to the hospice center, the cost is less, about $4 per week. To the extent the service is integrated into existing systems, costs are kept low. Even with these low costs, the majority of patients cannot even afford the medicines. Hospice Uganda is funded largely by small contributions and more recently, a few larger grants. Much of the money goes to training and advocacy, but patient care is also largely subsidized.

The following are lessons learned:

-

Using existing health facilities (government, private, and mission) as a base makes hospice care more affordable.

-

For HIV/AIDS, grafting palliative care knowledge onto existing support teams is affordable and effective.

-

Existing expertise in palliative care is very limited, so focused training is essential.

-

Palliative care must be adapted to the cultural and economic needs and resources of patients and families. These vary from country to country, and from tribe to tribe within countries.

-

Government support is essential, both for lowering legal barriers to the use of oral morphine and for support of the concept of palliative care.

Hospice Uganda has successfully begun a long process of assimilating palliative care into the lives of Africans in all types of places. Still, even in Uganda, only a few hundred of the estimated quarter million (out of the total population of 24 million) in pain at any one time currently receive adequate control of their symptoms.

Since 2001, Hospice Uganda has expanded its advocacy and training about innovative and low-cost ways to provide palliative care and morphine to other African countries. Hospice Uganda has introduced needs assessments in the catchment areas of the three hospice programs in the country, but these also serve as models. In 2002, WHO assisted five other countries in Africa with similar assessments as first steps toward establishing hospice programs, and this work continues. In 2006, the new African Palliative Care Association and partners sponsored a special workshop on opioid availability for palliative care for teams from six sub-Saharan African countries, using the template of the guidelines in WHO’s Achieving Balance in National Opioids Control Policy (WHO, 2000) to develop action strategies to improve patient access to oral morphine. In addition, 12 African countries are receiving funding assistance from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the U.S. bilateral program to assist 15 low-income countries with high rates of HIV infection and AIDS. One of PEPFAR’s stated aims is to improve palliative care for people with AIDS. This could be a means for countries to build a palliative care program that would be equally appropriate for people dying from cancer and other diseases.

PAIN AND PALLIATIVE CARE

An essential part of cancer control is palliative care and pain management, which includes patient access to opioid drugs. According to WHO, “A palliative care programme cannot exist unless it is based on a rational national drug policy,” and this includes “regulations that allow ready access of suffering patients to opioids” (WHO, 2002). One reason why pain control has been relatively slow to develop is that opioid pain medicines, while considered by international health authorities to be essential medicines, have been strictly regulated as narcotic drugs by government law enforcement and drug regulatory agencies to prevent diversion and abuse. Consequently, the cancer and palliative care community is faced with a unique challenge: how to develop cooperative relationships with government drug control and law enforcement agencies, leading to reform of overly restrictive opioid control policies at every level—international, national, and state or province.

The Impact of Pain

Unrelieved pain dramatically affects quality of life and sometimes the will to live. Patients with persistent pain rated as 5 or greater on a 10-point scale have clear and significant functional limitations that affect relationships, social activities, and ability to work and care for families (Daut et al., 1983). Increasing pain produces higher rates of depression and anxiety (Rosenfeld et al., 1996).

The suffering of an individual patient radiates throughout households, neighborhoods, and villages. Caregiver distress, anxiety, and depression are clearly associated with inadequate control of a family member’s symptoms. In places where the burden of care falls on the family, the persistence of pain and the suffering of the individual erodes the quality of life of family members. Family caregivers often have to give up their schooling or employment to remain home to care for a family member. In developing countries, the loss of patient or caregiver income may dramatically affect the social status of the family. Families of people dying from cancer who provide care at home—the preferred place for many—must face unrelieved pain and suffering daily with little or no access to the palliative care interventions that could vastly improve the quality of life of all involved (Joranson, 2004; Murray et al., 2003).

Pain in Patients With Cancer

Several well-defined acute and chronic pain syndromes are associated with cancer and its treatment (Table 7-1) (Breitbart, 2003; Foley, 1878, 1994; Hewitt et al., 1997; Portenoy and Lesage, 1999). The prevalence of cancer pain syndromes differs between high- and low-income countries. In

TABLE 7-1 Cancer-Related Chronic Pain Syndromes

|

Tumor-Related Syndromes |

|

|

Bone pain |

Multifocal or generalized bone pain |

|

|

Vertebral syndromes |

|

|

Back pain and epidural compression |

|

|

Pain syndromes of the bony pelvis and hip |

|

Headache and facial pain |

Intracerebral tumor |

|

|

Leptomeningeal metastases |

|

|

Base of skull metastases |

|

|

Orbital syndromeOrbital syndrome |

|

|

Parasellar syndrome |

|

|

Middle cranial fossa syndrome |

|

|

Jugular foramen syndrome |

|

|

Occipital condyle syndrome |

|

|

Clivus syndrome |

|

|

Sphenoid sinus syndrome |

|

Painful cranial neuralgias |

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia |

|

|

Trigeminal neuralgia |

|

Tumor involvement of the peripheral nervous system |

Tumor-related peripheral neuropathy |

|

Cervical plexopathy |

|

|

|

Brachial plexopathy |

|

|

Paraneoplastic painful peripheral neuropathy |

|

Pain syndromes of the viscera and miscellaneous tumor-related syndromes |

Hepatic distention syndrome |

|

Midline retroperitoneal syndrome |

|

|

Chronic intestinal obstruction |

|

|

|

Peritoneal carcinomatosis |

|

|

Malignant perineal pain |

|

|

Malignant pelvic floor myalgia |

|

|

Ureteric obstruction |

|

Cancer Therapy-Related Syndromes |

|

|

Postchemotherapy pain syndromes |

Chronic painful peripheral neuropathy |

|

Avascular necrosis of femoral or humeral head |

|

|

|

Plexopathy associated with intra-arterial infusion |

|

|

Gynecomastia with hormonal therapy for prostate cancer |

|

Chronic postsurgical pain syndromes |

Postmastectomy pain syndrome |

|

Postradical neck dissection pain |

|

|

|

Postthoracotomy pain |

|

|

Postoperative frozen shoulder |

|

|

Phantom pain syndromes |

|

|

Stump pain |

|

|

Postsurgical pelvic floor myalgia |

|

Chronic postradiation pain syndromes |

Radiation-induced peripheral nerve tumor |

|

Radiation-induced brachial and lumbosacral plexopathies |

|

|

Chronic radiation myelopathy |

Chronic radiation enteritis and proctitis |

|

|

Burning perineum syndrome |

|

|

Osteoradionecrosis |

|

SOURCE: Based on Foley (1979; 1994). |

|

low-income countries, where patients often present late in the course of their illness, tumor-related chronic cancer pain syndromes are more common than treatment-related syndromes.

Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer

Studies from around the world consistently report that 60 to 90 percent of patients with advanced cancer, and up to one-third of patients under active cancer treatment, experience moderate to severe pain, across all age groups, among men and women, and among ambulatory and hospitalized patients (Foley, 1979, 1999; Daut and Cleeland, 1982; Cleeland et al., 1988a; Cleeland et al., 1996; Stjernsward and Clark, 2003). Most studies are from Europe and North America, but results are similar in the few studies reported from developing countries, including India, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, and China.

The intensity, degree of pain relief, and effect of pain on quality of life in patients vary according to the type and stage of cancer, treatment, and personal characteristics. Pain syndromes are common. Key studies have found:

-

90 percent of ambulatory lung or colon cancer patients in the United States experienced pain more than one-quarter of the time; for 50 percent, pain interfered with general activity or work. Pain lasted a median of 4 weeks at moderate intensity (Portenoy et al., 1992).

-

60 percent of outpatients in an oncology clinic in the Netherlands were in pain, with 20 percent reporting moderate to severe pain (Schuit et al., 1998).

-

56 percent of patients followed by the U.S. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group reported moderate to severe pain half of the time, and for 36 percent, it interfered with daily functioning (Cleeland et al., 1994).

-

69 percent of cancer patients in France reported pain sufficient to interfere with their function (Larue et al., 1995).

-

Anxiety, depression, and history of previous substance abuse negatively influence the experience of cancer pain (Kelsen et al., 1995).

Most cancer pain is directly related to the tumor itself, including 85 percent of patients referred to an inpatient cancer pain consultation service, and 65 percent of patients seen in an outpatient cancer center pain clinic in the 1970s in the United States (Foley, 1979). Bone pain is the most common tumor-associated pain, followed by tumor infiltration of nerves, and infiltration and obstruction of internal organs. Tumors that commonly metastasize to bone, such as breast or prostate cancer, result in a higher prevalence of pain (80 percent) than do lymphomas and leukemias (Foley, 1979). The

prevalence and severity of pain increase with disease progression; fewer than 15 percent of patients with nonmetastatic disease report pain. Tumors near neurologic structures are more likely to cause pain. Cancer treatment causes pain in approximately 15 to 25 percent of patients receiving chemotherapy, surgery, or radiotherapy.

Burden of Pain in the Final Stages of Cancer

Pain-Days: A Metric for Moderate to Severe Pain

No standard metric describes the pain burden for people at the end of life. Measures used to quantify the effects of disease—disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), years of life lost, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs)— are less appropriate for the severe pain associated with dying. A transparent and direct measure, called pain-days, has been proposed (Foley et al., 2006), defined as the total number of person-days of moderate or severe pain requiring treatment with opioid drugs for adequate relief.

To the extent it is known, the patterns of pain from specific cancers at given stages are similar everywhere: a lung cancer patient dying in the United States and one dying in sub-Saharan Africa have similar pain, if untreated. But different cancers produce different symptoms (from the disease and from the treatment), so the mix of cancers in a country strongly influences the overall pain pattern. The mix is highly variable: The common cancers of many poor countries (e.g., of the liver, stomach, and esophagus) are less common in wealthy countries.

The two elements that determine the number of cancer pain-days in a population are (1) the numbers of people dying painful deaths and (2) the average prevalence and duration of severe pain in those individuals.

Numbers of Deaths from Cancer

About 2.1 million deaths from cancer occur annually in LMCs worldwide, and both the mortality rates and numbers are increasing. In contrast to wealthier countries, in developing countries about 80 percent of cancers are detected very late, when palliation is most needed (Stjernsward and Clark, 2003).

Prevalence and Duration of Severe Pain in Those Dying from Cancer

The extent of severe pain among people dying of cancer is poorly documented. Expert opinion suggests about 80 percent of people dying from cancer experience moderate or severe pain during their final days, and the average duration of severe pain is 90 days (Foley et al., 2006). This varies

by type of cancer and the course of the particular cancer. Each patient is different and each situation requires assessment by a knowledgeable person to determine the degree of pain relief needed. The main point is that most people with cancer would benefit greatly from pain relief, and for most, the need will be greatest during the final days, weeks, or months.

INTERVENTIONS FOR PAIN RELIEF

The goal of pain treatment is not to cure disease, but to improve quality of life: to allow the patient to function as effectively as possible for as long as possible, and to die with as little pain as possible. Pain can occur at any stage of cancer, but is most severe near the end of life, when the strongest drugs—opioids—are needed. Interventions used for pain relief include drug treatment; radiotherapy; and anesthetic, neurosurgical, psychological, and behavioral approaches, each of which is appropriate for certain patients and situations. Analgesic drugs are the mainstay of treatment, however.

For patients with moderate to severe pain, opioids such as morphine that are full agonists, meaning that they bind completely to pain-transmitting receptors, are indispensable and should be easily available in adequate doses to all cancer patients who need them, wherever they are.

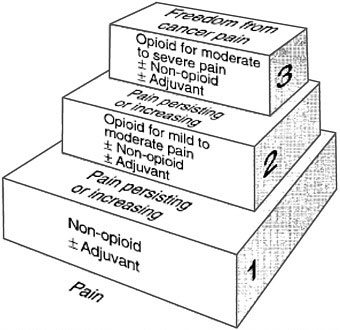

WHO Cancer Pain Relief Guidelines: The Three-Step Analgesic Ladder

The WHO Cancer Unit created a Cancer Pain Relief Program, including guidelines for the treatment of cancer pain (WHO, 1990, 1996). Its “Three-Step Analgesic Ladder” (the ladder) (Figure 7-2) embodies the concept that analgesic drug therapy is the mainstay of treatment for the majority of patients with cancer pain, and that a strong opioid (morphine) is an absolute necessity to control severe pain (Table 7-2). The ladder, which is accepted internationally, is equally appropriate for patients with HIV/AIDS (O’Neill et al., 2003).

The steps in the ladder match increasing pain severity with the appropriate drug treatment. New patients can enter at any step according to the severity of their pain. Step 1 is for mild pain and treatment with non-opioid drugs which, although they are widely available, can be expensive. A patient with mild pain from bone metastases could be helped by paracetamol, aspirin, or one of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). In a patient with mild pain from a peripheral neuropathy, the combination of a non-opioid with a tricyclic antidepressant (e.g., amitriptyline) or an anticonvulsant (e.g., gabapentin) would be appropriate.

Step 2 describes patients with moderate pain or those who fail to achieve adequate relief after a trial of a non-opioid analgesic. They are candidates for a combination of a non-opioid (e.g., aspirin or acetaminophen) with

FIGURE 7-2 The Three-Step Analgesic Ladder.

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from WHO (1996). Copyright 1996 by WHO.

an opioid (e.g., codeine) and also partial agonists such as propoxyphene, buprenorphine, or tramadol.

Step 3 is for patients with moderate to severe pain who require a pure opioid agonist for relief, such as morphine, hydromorphone, methadone, fentanyl, oxycodone, and levorphanol. Morphine is effective and can be less expensive than other strong opioids; however, several opioids should be available for rotation because efficacy and side effects differ between drugs and individuals. There are no recommended standard or maximum doses for opioid drugs—starting doses of oral morphine may be as little as 5 mg and therapeutic doses for severe pain may go up to more than 1,000 mg every 4 hours. The correct dose is the dose that relieves the pain. Non-opioid analgesics are often used in combination to improve efficacy and to spare opioid side effects.

Adjuvant drugs should be available at every step of the ladder to treat side effects of analgesics or provide additive analgesia (Table 7-2). Drugs in the following categories are essential to full use of the ladder: antiemetics, laxatives, antidiarrheal agents, antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, anxiolytics, and psychostimulants.

The practical application of the ladder is summarized in five phrases: by mouth, by the clock, by the ladder, for the individual, and by attention

TABLE 7-2 Basic Drug List for Cancer and AIDS Pain Relief: Analgesics and Adjuvant Drugs

|

Category |

Basic Drugs |

Alternatives |

|

Analgesics |

||

|

Non-opioids |

acetylsalicylic acid (ASA; aspirin) paracetamol ibuprofen indomethacin |

choline magnesium trisalicylate diflunisal naproxen diclofenac celecoxib rofecoxib |

|

Opioids for mild to moderate pain |

codeine |

dihydrocodeine hydrocodone tramadol |

|

Opioids for moderate to severe pain |

morphine |

methadone hydromorphone oxycodone pethidine buprenophine fentanyl |

|

Opioid antagonists |

naloxone |

nalorphine |

|

Adjuvant Drugs for Analgesia and Symptom Control |

||

|

Antiemetics |

prochlorperazine |

metaclopramide ondansetron |

|

Laxatives |

senna sodium docusate mineral oil lactulose magnesium hydroxide |

bisacodyl bran dantron sorbitol |

|

Antidiarrheal agents |

loperamide diphenoxylate HCl/atropine sulfate |

paregoric |

|

Antidepressants (adjuvant analgesics) |

amitriptyline |

imipramine paroxetine |

|

Antipsychotic |

haloperidol |

|

|

Anticonvulsants (adjuvant analgesics) |

gabapentin carbamazepine |

valproic acid |

|

Corticosteroids |

prednisone dexamethasone |

prednisolone |

|

Anxiolytics |

diazepam lorazepam midazolam |

clonazepam |

|

Psychostimulants |

methylphenidate |

pemoline |

|

SOURCE: Foley et al. (2003). |

||

to detail. Drugs given orally are the core treatment; other routes, including sublingual, transdermal, rectal, or subcutaneous may be needed for some patients. Analgesics should be given around the clock at fixed intervals to provide continuous relief. The dose should be titrated against the patient’s pain, increasing gradually until pain is relieved or side effects are not tolerated. Effective doses should be administered on a regular schedule that maintains pain relief. Rescue doses for intermittent breakthrough pain should be readily available and administered as needed.

Effectiveness of Opioids in Pain Relief

Current recommendations for morphine use date from the mid-1980s, when WHO developed the ladder. Morphine has a much longer history, however (Wiffen, 2003). It was first extracted from opium in 1803. The properties of opium itself—a resin derived from the sap of the poppy—had been known for centuries, and noted in Pliny’s Historia Naturalis in 77 A.D. In the 1950s, Brompton’s cocktail, a mixture of morphine, chloroform, cocaine, and sometimes alcohol, was in vogue in England.

Although morphine’s oral efficacy was doubted many years ago, the effectiveness of oral morphine in relieving pain today is unquestioned. The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality sponsored an exhaustive review entitled Management of Cancer Pain (Goudas et al., 2001), which assumed the efficacy of morphine, despite the absence of large clinical trials testing morphine against no treatment or placebo. It concentrated instead on the relative efficacy of analgesics currently used for cancer pain. The evidence rests heavily on seminal studies of the 1960s and 1970s, when a group of investigators conducted a series of clinical trials comparing the analgesic potency of various opioid analgesics for cancer pain. Placebos were used in some studies, providing the only such comparisons of morphine versus no treatment. Most recent clinical trials have compared newer opioid formulations with morphine and other analgesics.

A Cochrane Collaboration systematic review, Oral Morphine for Cancer Pain (Wiffen, 2003), concludes:

This literature review, and many years of use, show that oral morphine is an effective analgesic in patients who suffer pain associated with cancer. It remains the gold standard for moderate or severe pain.

The Cochrane review also affirmed that pain relief could be achieved in most patients by titrating the dose, and that, although sustained-release forms may be more convenient, they are not more effective than the standard immediate-release form of morphine (the least expensive formulation). They noted also that “a small number of patients … do not benefit from morphine or … may develop intolerable side effects.”

Effectiveness of the Three-Step Analgesic Ladder

Field testing—confirmed by broad clinical experience—has demonstrated that 70–90 percent of cancer patients can achieve pain control if the ladder is used appropriately (Goudas et al., 2001). The evidence comes largely from developed countries, including studies using the Brief Pain Inventory (Bernabei et al., 1998), but experience has begun to accumulate in developing countries suggesting similar effectiveness (Cleeland et al., 1988b). Although the ladder has not been validated in formal AIDS studies, recent clinical reports have described its successful application to pain management in AIDS (Anand et al., 1994; Kimball and McCormick, 1996; McCormack et al., 1993; Newshan and Lefkowitz, 2001; Newshan and Wainapel, 1993; Schofferman and Brody, 1990).

Trials validating the specific choice of agents and their sequence within the ladder are limited (Mercadante, 1999), and few studies have examined relative efficacy of different drugs for specific types of pain (Eisenberg et al., 1994). There are commonly held beliefs, for example, that NSAIDs are particularly beneficial for bone pain, and that opioids are of little benefit for neuropathic pain. However, a meta-analysis of NSAIDs for metastatic bone pain suggests that they are no more effective than opioids (Eisenberg et al., 1994). Furthermore, a growing body of clinical trials has documented the effectiveness of opioids for neuropathic pain when titrated to effect (Foley, 2003).

Despite some gaps in knowledge, the ladder—with its associated drugs— is an effective tool for managing pain associated with cancer, from early to late stages. In an ideal world, a physician or other authorized and trained health workers would prescribe appropriately throughout the course of illness. Around the world, however, most patients are likely to self-medicate pain with weak or ineffective analgesics and traditional medicines they buy over the counter, sometimes leading to complications. In the real world, many people with cancer never reach the formal health care system, and if they do, they have late-stage disease and severe pain that requires oral morphine, which is largely unavailable in the health care systems of LMCs as well as some more developed countries.

ADEQUACY OF AND BARRIERS TO PAIN CONTROL IN LMCS

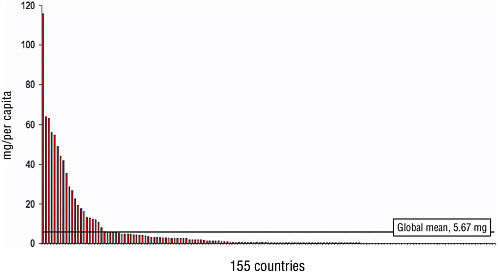

The adequacy of pain control in populations is not easily measured. A useful and available surrogate is the per-capita consumption of morphine (Joranson, 1993), a figure based on mandatory annual reports by national governments to the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB). Of the 27 million kilograms of morphine used legally in 2002, 78 percent went to six countries—Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The rest was consumed by the other 142 countries

that reported. Morphine is largely unavailable in Africa, the eastern Mediterranean, and Southeast Asia (Table 7-3 and Figure 7-3).

Legal Controls on Opioid Drugs

The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, amended by the 1972 Protocol (United Nations, 1961), is an international treaty that aims both to prevent the illicit production of, trafficking in, and nonmedical use of narcotic drugs and also to ensure their availability for medical and scientific needs. The INCB, established in 1968 by the Single Convention, is the independent, quasi-judicial organization that implements the Single Convention.

The Single Convention requires that all governments (even nonsignatories) estimate annually the amounts of opioids needed for medical and scientific purposes and report annually on imports, exports, and distribution to the retail level (consumption). It also sets out the following principles on which countries can base their own policies and regulations:

-

Individuals must be authorized to dispense opioids by virtue of their professional license or be specially licensed to do so.

-

Opioids may only be transferred between authorized parties.

-

Opioids may be dispensed only with a medical prescription.

-

Security and records are required.

Many governments impose tighter restrictions that constitute significant barriers to patient access, such as burdensome licensing and prescription procedures, heavy penalties for mistakes, and limiting the amount or the number of days or the diagnoses for which an opioid prescription can be written (International Narcotics Control Board, 1989; WHO, 1996).

Cost-Effectiveness of Pain Medications

Foley and colleagues (Foley et al., 2006) analyzed the costs and cost-effectiveness of pain medications, including oral morphine, in three LMC countries: Uganda, Romania, and Chile. Based on this analysis, the cost of oral morphine ranged from $216 to $420 (Table 7-4) per year of pain-free life gained in the three sample countries. The next question is whether the pain relief that could be achieved would be worth the cost. We know that pain-free days are valued highly by patients. A day lived with the certainty of experiencing severe pain is of very low value, perhaps even lower than death itself (Furlong et al., 2001; Le Gales et al., 2002). Bryce and colleagues (2004) found that people said they were willing to give up several months of healthy life for access to good end-of-life care. Patients in low-income

TABLE 7-3 Morphine Consumption by Country According to Income Level, per Capita, 2004

|

Morphine mg/capita |

Low |

Lower Middle |

Upper Middle |

High |

|

≤0.01 |

Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Central African Republic Congo, Dem. Rep. Cote d’Ivoire Guinea Mozambique Pakistan Sao Tome and Principe Sierra Leone Yemen, Rep. |

Cameroon |

Estonia |

|

|

>0.01–0.1 |

Benin Bhutan Mali Myanmar Nepal Rwanda Senegal Uzbekistan Vietnam Zambia |

Algeria Bolivia Cape Verde Egypt, Arab Rep. Guatemala Indonesia Marshall Islands |

Libya |

|

|

>0.1–1.0 |

Chad Guinea-Bissau Kenya Mongolia Tanzania Uganda Zimbabwe |

Azerbaijan Belarus Bosnia and Herzegovina China Colombia Dominican Republic Ecuador El Salvador Iran, Islamic Rep. Jordan Kazakhstan Micronesia, Fed. Sts. Moldova Morocco Nicaragua Paraguay Peru Philippines Sri Lanka |

Botswana Dominica Grenada Mauritius Mexico Oman Palau Panama Russian Federation St. Vincent and the Grenadines Turkey Venezuela, RB |

Bahrain Brunei Darussalam Greece Kuwait Qatar Saudi Arabia United Arab Emirates |

|

Morphine mg/capita |

Low |

Lower Middle |

Upper Middle |

High |

|

|

Suriname Swaziland Syrian Arab Republic Thailand Tonga Turkmenistan Vanuatu |

|

|

|

|

>1.0–10.0 |

|

Brazil Bulgaria Georgia Jamaica Macedonia, FYR Namibia Serbia and Montenegro Tunisia Ukraine |

Argentina Barbados Chile Costa Rica Czech Republic Hungary Latvia Lebanon Lithuania Malaysia Poland Romania Seychelles Slovak Republic South Africa Uruguay |

Andorra Bahamas Cyprus Finland French Polynesia Hong Kong Israel Italy Japan Korea, Rep. Macao Malta Netherlands Antilles New Caledonia Portugal Singapore Slovenia |

|

>10.0–20.0 |

|

|

|

Belgium Germany Ireland Netherlands Spain United Kingdom |

|

>20.0 |

|

|

|

Australia Austria Canada Denmark France Iceland New Zealand Norway Sweden Switzerland United States |

|

SOURCE: Pain and Policy Studies Group, University of Wisconsin/WHO Collaborating Center (2006). |

||||

FIGURE 7-3 Global morphine consumption for 155 countries (mg/per capita, 2004).

SOURCE: Pain and Policy Studies Group, University of Wisconsin/WHO Collaborating Center (2006).

countries place as great or even greater value on pain relief as patients in high-income countries (Cleeland et al., 1988; Murray et al., 2003).

IMPROVING PALLIATIVE CARE IN LMCS

Only a handful of LMCs have thus far made significant progress in palliative care, and each case is unique. Although there is no recipe for either initiating or upgrading palliative care services in countries with little or no

TABLE 7-4 Cost Analysis Results (all costs in $US, 2002)

|

|

Uganda |

Chile |

Romania |

|

Total incremental annual cost of oral morphine (US$ millions) |

$4.2 m |

$1.0 m |

$2.2m |

|

Incremental annual cost per capita |

$0.18 |

$0.06 |

$0.10 |

|

Incremental number of pain-days per year avoided with oral morphine |

3.6 m |

0.9 m |

1.9 m |

|

Incremental cost per person-day of pain avoided |

$1.17 |

$1.17 |

$1.17 |

|

Incremental cost per year of pain-free life added |

$420 |

$420 |

$420 |

|

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Foley et al. (2006). Copyright 2006 by the World Bank. |

|||

capacity, common elements suggest some ways forward. At the heart of change invariably is a small core of motivated, dedicated, and charismatic leaders who champion palliative care and hospice services. Often, these are health care professionals who have been burdened with the care of patients dying in unrelieved pain. Progress usually depends on links to expertise and partners from inside and outside the country to assist with a variety of unfamiliar tasks. These include expertise in setting up nongovernmental organizations, creating an inclusive platform for advocacy, and training and mentoring enough people to reach the critical mass needed to begin providing services. Technical, financial, and motivational assistance to local leaders can make these tasks manageable. These same the local leaders also become involved in the advocacy work necessary to obtain opioid pain medications and to address the barriers to patient access.

Improving Pain Control as the Entry Point in Improving Palliative Care

In the many countries that lack adequate pain control and palliative care, the basic reasons tend to be similar: low priority of pain relief and palliative care in the national health care system, lack of knowledge about how to treat pain on the part of health care practitioners, patient fears and misunderstanding of the medications (including opioid analgesics), and regulatory barriers to opioid analgesics. WHO’s position (which is widely accepted) is that a palliative care program cannot exist without patient access to opioid drugs. Creating access where it does not exist invariably requires policy activities at national and local levels within a country, as well as international interactions, e.g., with the INCB. It involves not only the health care sector, but regulators, law enforcement, and others. The centrality of drug availability has made it a cornerstone for the development of palliative care in LMCs. The University of Wisconsin Pain and Policy Studies Group (PPSG) on Policy and Communications in Cancer Care, or WHOCC (a WHO Collaborating Center), is a leading international resource for providing assistance to national efforts to expand access to opioid drugs as a means of improving palliative care. The PPSG has tried different approaches to moving pain control forward in different parts of the world by providing tools and training for professionals in the public and private sectors and fostering collaboration among different sectors within countries.

A major thrust of PPSG’s work has been, in collaboration with WHO and the Open Society Institute, regional workshops, of which four have been held: in Quito for six Latin American countries (in 2000), in Gabarone for five sub-Saharan African countries (2002), in Budapest for six central and Eastern European countries (in 2002), and in Entebbe (in 2006) for six sub-Saharan countries. More recently (October 2006), PPSG hosted leaders in palliative care from 8 LMCs in Wisconsin for one week of training and

discussion. An aim of each of these meetings has been the development of an action plan for each participating country to improve the availability of opioid medications for relief of pain and suffering of cancer and AIDS patients at the end of life.

A weakness of the regional workshops had been lack of resources for follow-up by PPSG and for taking forward the plans developed on the part of the participants. This was possible in only limited cases (e.g., Romania, described in detail below). A change with the October 2006 effort is that each participant is also being supported for a part of his or her time on return to work, and the PPSG will be involved with each one.

PROGRESS IN PAIN CONTROL IN ROMANIA: A CASE EXAMPLE

A team from Romania participated in the Budapest regional workshop and emerged as ready to pursue change more immediately than any other country team. This section recounts their situation and progress.

Prerevolution narcotics policies dating back more than 35 years frequently prevented physicians in Romania from providing pain relief to cancer and AIDS patients even at the end of life. Romania’s annual medical consumption of morphine, at 2.2 mg per capita (2001 data), was well below the global mean and among the lowest in Eastern Europe. After the workshop in Budapest in 2002 (see above), Romania was selected among the participating countries for a follow-up national project. The situation was that palliative care was severely impeded by regulatory barriers, leaders in palliative care wanted to work with the government to address the barriers, and the Ministry of Health appointed a Palliative Care Commission to study the law and regulations and recommend changes, demonstrating that a key ingredient—political will—was present.

The Opioid Regulatory Situation

Just a few years ago, the regulations for prescribing opioids in Romania were so complicated, restrictive, and burdensome that it was sometimes impossible for outpatients to receive oral morphine. The least restrictive option was a single 3-day prescription, even for a dying cancer patient. For certain exceptions, including incurable cancer (but not HIV/AIDS), with governmental permission, an application could be made for “long-term prescribing” for a 3-month period with each prescription lasting a maximum of 10 to 15 days. Many forms, some requiring special stamps, had to move from the hospice physician to the district oncology hospital, to the district health department, and finally to the patient’s family physician, who would write a triplicate prescription for the pharmacy, where all the paperwork came together. Modern cancer pain management was basically precluded.

Process of Change

From 2003 to 2005, the Ministry of Health and its Palliative Care Commission examined and prepared a revision of the national narcotics law and regulations, with review and comment by the PPSG at the University of Wisconsin at Madison (Ryan, 2005). A new law eliminating the regulatory barriers was adopted by the Romanian Parliament in November 2005. Implementing regulations consistent with the new law have been adopted. The study and drafting process took place during a visit from a five-member Romanian team to the PPSG in late 2004.

Under the new law and regulations, the previous special authorization procedure is no longer necessary for opioids to be prescribed. Physicians now have, for the first time, independent ability to prescribe an amount for 30 days with no limit on dose. Patient eligibility based on diagnosis has been removed (Mosoiu et al., 2006).

The example being set by Romania could be a model for Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union countries that lack policy models for improving opioid availability. However, the situation is unique in each country and change will still require country-by-country approaches and outside assistance as the situation requires.

The WHOCC and Development of Pain Control and Palliative Care in India1

For decades, the only morphine available in India was injectable, used for postoperative pain. Enactment of a strict national narcotics law in 1985 caused legal morphine consumption reported by the Government of India to decline even further, from a high of 573 kilograms to 18 kilograms in 1997, among the lowest per-capita consumption in the world. The reporting of morphine consumption has since ceased. Ironically, much of the world’s morphine supply originates in legal poppy cultivation in India, but only a trickle was used domestically. It was during the period of declining consumption that international efforts to promote pain control and palliative care programs began to reach India. The first program, Shanti Avedna Ashram, was established in 1986. In 1992, pain relief and the availability of morphine were designated priorities in the National Cancer Control Programme and WHO provided substantial education in palliative care.

The Ministry of Health convened a series of national workshops from 1992 to 1994 in cooperation with the WHOCC to find out why morphine

was so difficult to obtain. The following experience, recounted by a former Narcotics Commissioner of India, is instructive:

… [Hospital name] is a referral hospital for cancer management. The annual requirement of morphine is approximately 10,000 tablets of 20 mg. But the Institute has not been able to procure a single tablet till date, primarily due to the stringent state laws and multiplicity of licenses. After a lot of effort, the Institute had been able to obtain the licenses in 1994 and had approached [a manufacturer] for a supply of tablets. At the relevant time [the manufacturer] did not have the tablets in stock and by the time the tablets could be arranged, the licenses had expired. The doctors at the Institute and the associated pain clinic have stopped prescribing morphine tablets because they would not be available (Joranson et al., 2002).

The situation was so extreme that in 1999, the INCB called on the Government of India to take measures to make morphine available for medical uses (Joranson et al., 2002).

In 1994, an initiative begun by the WHOCC, the Indian Association of Palliative Care, and the Pain and Palliative Care Society systematically studied the reasons for the lack of morphine. The 1985 national law passed to diminish narcotic trafficking and abuse included stringent punishments for narcotics infractions, which increased doctors’ reluctance to prescribe morphine and pharmacists’ reluctance to stock it. At the state level, palliative care programs had to obtain multiple licenses from two different departments to obtain opioids and to move morphine between different states in India. The result was gridlock.

In 1997, the WHOCC developed a proposal to reduce the number of licenses and extend their period of validity, among other measures. The Revenue Secretary in New Delhi accepted the recommendations and in 1998, sent instructions to all state governments to adopt a model simplified licensing rule developed from the proposal. This request had little initial effect, so the WHOCC and the WHO Demonstration Project at the Pain and Palliative Care Society in Calicut held workshops with officials and cancer and palliative care stakeholders in several states to encourage the needed changes. Gradually, rules have begun to change. By 2002, 7 of 28 states or territories had adopted the model rule, but only in the state of Kerala (population 32 million) has it been implemented successfully, so that community-based palliative care programs can be licensed to order morphine and thus can provide uninterrupted access to it.

Four factors have led to the success in Kerala:

-

The state government simplified the licensing process and agreed that oral morphine could be available to palliative care centers with at least one doctor having at least one month of practical experience in palliative care;

-

The national Drugs Controller exempted palliative care programs from needing a drug license, thereby eliminating the need for a pharmacist and the associated costs;

-

A hospital pharmacy in the state became a local manufacturer and distributor of inexpensive oral morphine tablets, obtaining its supply of morphine powder from the national factory; and

-

A palliative care network has been established, consisting of about 50 small programs, each having a physician licensed to obtain and dispense morphine. Statewide coverage has increased to about 20 percent of those needing palliative care.

Another New Approach in India

While the success in Kerala is remarkable, the overall picture in the rest of India is not. Those who have led in Kerala, through “Pallium India,” a nongovernmental organization, and the WHOCC are beginning to test a new strategy to extend palliative care with oral morphine to other parts of India where cancer hospitals lack palliative care and oral morphine. The plan builds on the fact that palliative care in India (as elsewhere) started and is growing mainly as a result of local interest and leadership, rather than through policy directives from the national government (although the fact that the government has pronounced palliative care a priority enables further development). The new approach is aimed at cancer institutions with little or no palliative care and is based on the “WHO triangle,” which asserts that the three basic ingredients of success are policy, education and training, and drug availability. The approach seeks to integrate the following into cancer institutions: (1) a policy to provide palliative care; (2) staff training about pain control and morphine; and (3) assurance of a continuous supply of oral morphine.

The availability of funds will allow the project to establish palliative care in three cancer centers over a period of 2 years. To begin with, all cancer centers in the country were informed of the project and given the opportunity to apply. The response was more enthusiastic than expected, with 27 cancer institutions applying. Three centers were selected in the states of Manipur, Mizoram, and Uttar Pradesh. The program has two phases: phase 1 involves training two professionals from each center and phase 2 involves education of local health care professionals and the public when the trained professionals return home. Phase 1 has been completed and the teams have returned to their cancer centers. By prior agreement (a Memorandum of Understanding), the home cancer center will be obligated to do the following:

-

Initiate a palliative care service within 3 months.

-

Include the cost of immediate-release morphine in their annual drug budget, take steps to ensure its uninterrupted availability, and ensure its rational use with proper documentation. Pallium India and the WHOCC will assist the centers with these tasks.

-

Contribute the time of the trainees during the training period, and ensure that the trained personnel will be able to devote at least half of their working time to palliative care.

-

Provide the funds to continue palliative care and morphine availability when the project terminates at the end of 2 years.

-

Evaluate outcomes by submitting statistics on patient numbers, morphine prescriptions, and dispensing, according to agreed-on specifications.

Pallium India and the WHOCC will support and assist the trainees back in their home centers through periodic follow-up and e-mail consultations.

Phase 2 involves education of local health care professionals, the public, and institution administrators in each locality. The program will be directed primarily at professionals in the institution, but would be available to other professionals in the area, medical students, the public, and administrators. The acceptance of the community is essential to successful establishment of palliative care. Each 1- to 2-day workshop would take place as soon as possible after the return of the trained professionals, but not later than 6 months.

Experience in Kerala has been that once a proper palliative care program has been developed and its benefits become apparent, it can be sustained by community support. Cancer pain being emotive, support from the community is usually forthcoming. Over the long term, a visible palliative care service in one location should result in more such facilities developing elsewhere. Evaluation by the organizers will, of course, be carried out during and after the program. The external funding cost of the 2-year program for three institutions is estimated at about $40,000, provided by the U.S. National Cancer Institute. This does not include costs incurred by the institutions participating.

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Palliative care is an essential component of cancer control that is lacking or vastly underrepresented in LMCs. Because cancers tend to be recognized only at advanced stages in LMCs (and curative treatment may not be available or at least accessible), palliative care is particularly important in these countries. Among the elements of palliative care, pain control is the most essential. Severe pain is common at the end stages of many cancers, degrading quality of life for the patient and family. Palliative care cannot be adequate without pain control, which requires the use of opioid analgesics such as

morphine. The legal and societal barriers to providing oral morphine to cancer patients (and others) at the community level, where it is needed, are formidable in many or most LMCs (and many high-income countries), even though the actual cost of the intervention is modest. Successes in establishing palliative care with pain control in a few places—such as Romania, India, and Uganda—demonstrate that change is possible, with considerable effort. Building on these experiences as models, it may be possible to accelerate the pace in other countries. The knowledge of how to do this now exists and should be applied more widely.

RECOMMENDATION 7-1. Governments should collaborate with national organizations and leaders to identify and remove barriers to ensure that opioid pain medications, as well as other essential palliative care medications, are available under appropriate control. The INCB and WHO should provide enhanced guidance and support, and assist governments with this task.

RECOMMENDATION 7-2. Palliative care, not limited to pain control, should be provided in the community to the extent possible. This may require developing new models, including training of personnel and innovations in types of personnel who can deliver both psychosocial services and symptom relief interventions.

REFERENCES

Anand A, Carmosino L, Glatt AE. 1994. Evaluation of recalcitrant pain in HIV-infected hospitalized patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 7(1):52–56.

Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, Landi F, Gatsonis C, Dunlop R, Lipsitz L, Steel K, Mor V. 1998. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association 279(23):1877–1882.

Breitbart W. 2003. Pain. In: O’Neill JF, Selwyn P, Schietinger H, eds., A Clinical Guide to Supportive and Palliative Care for HIV/AIDS. Washington, DC: Health Resources and Services Administration. Pp. 85–122.

Bryce CL, Loewenstein GARMSJ, Wax RS, Angus DC. 2004. Quality of death: Assessing the importance placed on end-of-life treatment in the intensive-care unit. Medical Care 42(5):423–431.

Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, Edmonson JH, Blum RH, Stewart JA, Pandya KJ. 1994. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 330(9):592–596.

Cleeland CS, Ladinsky JL, Serlin RC, Thuy NC. 1988. Multidimensional measurement of cancer pain: Comparisons of U.S. and Vietnamese patients. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 3(1):23–27.

Cleeland CS, Nakamura Y, Mendoza TR, Edwards KR, Douglas J, Serlin RC. 1996. Dimensions of the impact of cancer pain in a four country sample: New information from multidimensional scaling. Pain 67(2–3):267–273.

Daut RL, Cleeland CS. 1982. The prevalence and severity of pain in cancer. Cancer 50(9):1913–1918.

Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC. 1983. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain 17(2):197–210.

Eisenberg E, Berkey CS, Carr DB, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. 1994. Efficacy and safety of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for cancer pain: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology 12(12):2756–2765.

Foley KM. 1979. Pain syndromes in patients with cancer. In: Foley KM, Bonica JJ, Ventafridda V, eds. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. New York: Raven Press.

Foley KM. 1994. Cancer pain syndromes. In: Stanley TH, Ashburn MA, eds. Anesthesiology in Pain Management. Amsterdam: Kluwer Academic Publisher. Pp. 287–303.

Foley KM. 1999. Pain assessment and cancer pain syndromes. In: Doyle D, Hank G, MacDonald N, eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Foley KM. 2003. Opioids and chronic neuropathic pain. New England Journal of Medicine 348(13):1279–1281.

Foley KM, Wagner JL, Joranson DE, Gelband H. 2006. Pain control for people with cancer and AIDS. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, eds. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 981–993.

Furlong WJ, Feeny DH, Torrance GW, Barr RD. 2001. The Health Utilities Index (HUI) system for assessing health-related quality of life in clinical studies. Annals of Medicine 33(5):375–384.

Goudas L, Carr DB, Bloch R. 2001. Management of Cancer Pain. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 35. AHRQ Publication No. 02-E002. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Hewitt DJ, McDonald M, Portenoy RK, Rosenfeld B, Passik S, Breitbart W. 1997. Pain syndromes and etiologies in ambulatory AIDS patients. Pain 70(2–3):117–123.

International Narcotics Control Board. 1989. Demand for and Supply of Opiates for Medical and Scientific Needs. New York: United Nations.

Joranson DE. 1993. Availability of opioids for cancer pain: Recent trends, assessment of system barriers. New World Health Organization guidelines, and the risk of diversion. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 8(6):353–360.

Joranson DE. 2004. Regulations for Prescribing Opioids in Europe and Romania. Bucharest, Romania.

Joranson DE, Rajagopal MR, Gilson AM. 2002. Improving access to opioid analgesics for palliative care in India. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 24(2):152–159.

Kelsen DP, Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Niedzwiecki D, Passik SD, Tao Y, Banks W, Brennan MF, Foley KM. 1995. Pain and depression in patients with newly diagnosed pancreas cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 13(3):748–755.

Kimball LR, McCormick WC. 1996. The pharmacologic management of pain and discomfort in persons with AIDS near the end of life: Use of opioid analgesia in the hospice setting. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 11(2):88–94.

Larue F, Colleau SM, Brasseur L, Cleeland CS. 1995. Multicentre study of cancer pain and its treatment in France. British Medical Journal 310(6986):1034–1037.

Le Gales C, Buron C, Costet N, Rosman S, Slama PR. 2002. Development of a preference-weighted health status classification system in France: The Health Utilities Index 3. Health Care Management Science 5(1):41–51.

McCormack JP, Li R, Zarowny D, Singer J. 1993. Inadequate treatment of pain in ambulatory HIV patients. Clinical Journal of Pain 9(4):279–283.

Mercadante S. 1999. World Health Organization guidelines: Problem areas in cancer pain management. Cancer Control 6(2):191–197.

Mosoiu D, Ryan KM, Joranson DE, Garthwaite JP. 2006. Reform of drug control policy for palliative care in Romania. Lancet Online DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68482-1.

Murray SA, Grant E, Grant A, Kendall M. 2003. Dying from cancer in developed and developing countries: Lessons from two qualitative interview studies of patients and their carers. British Medical Journal 326(7385):368–371.

Newshan G, Lefkowitz M. 2001. Transdermal fentanyl for chronic pain in AIDS: A pilot study. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 21(1):69–77.

Newshan GT, Wainapel SF. 1993. Pain characteristics and their management in persons with AIDS. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 4(2):53–59.

O’Neill JF, Selwyn PA, Schietinger H. 2003. A Clinical Guide to Supportive and Palliative Care for HIV/AIDS. Washington, DC: Health Resources and Services Administration.

Pain and Policy Studies Group. 2006. Morphine consumption figures [unpublished].

Portenoy RK, Lesage P. 1999. Management of cancer pain. Lancet 353(9165):1695–1700.

Portenoy RK, Miransky J, Thaler HT, Hornung J, Bianchi C, Cibas-Kong I, Feldhamer E, Lewis F, Matamoros I, Sugar MZ, Olivieri AP, Kemeny NE, Foley KM. 1992. Pain in ambulatory patients with lung or colon cancer: Prevalence, characteristics, and effect. Cancer 70(6):1616–1624.

Rajagopal MR, Joranson DE, Gilson AM. 2001. Medical use, misuse, and diversion of opioids in India. Lancet 358(9276):139–143.

Rajagopal MR, Venkateswaran C. 2003. Palliative care in India: Successes and limitations. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy 17(3–4):121–128.

Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, McDonald MV, Passik SD, Thaler H, Portenoy RK. 1996. Pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. Impact of pain on psychological functioning and quality of life. Pain 68(2–3):323–328.

Ryan K. 2005. Progress to remove regulatory barriers to palliative care in Romania. Palliative Care Newsletter 1(4).

Schofferman J, Brody R. 1990. Pain in far advanced AIDS. In: Foley KM, Bonica JJ, Ventafridda V, eds. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. New York: Raven Press.

Schuit KW, Sleijfer DT, Meijler WJ, Otter R, Schakenraad J, Van den Bergh FCM, Meyboom-De Jong B. 1998. Symptoms and functional status of patients with disseminated cancer visiting outpatient departments. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 16(5): 290–297.

Stjernsward J, Clark D. 2003. Palliative medicine—a global perspective. In: Doyle D, Hanks GWC, Cherny N, Calman K, eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 3nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

United Nations. 1961. Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. [Online] Available: http://www.incb.org/e/conv/1961/incb.org/e/conv/1961/ [accessed 7/12/04].

WHO (World Health Organization). 1990. Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care, Technical Report Series 804. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

WHO. 1996. Cancer Pain Relief. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

WHO. 2000. Achieving Balance in National Opioids Control Policy: Guidelines for Assessment. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

WHO. 2002. National Cancer Control Programmes: Policies and Managerial Guidelines. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2002. Assuring Availability of Opioid Analgesics for Palliative Care: Report of a WHO Workshop Held in Budapest, Hungary; 25–27 February 2002. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Wiffen PJ. 2003. Pain and palliative care in The Cochrane Library: Issue number 4 for 2002. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy 17(2):95–98.