5

Evaluating the Department of Health and Human Services Dissemination and Communication Efforts

INTRODUCTION

The committee’s charge included evaluating the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’s) efforts to disseminate the research findings emerging from projects it undertook under its Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Department of Energy (DOE) to affected workers and communities. For the purposes of this report and consistent with its statement of task, the committee drew a distinction between dissemination and communication in the programs of HHS and DOE in pursuit of each objective. This distinction is grounded both in formal definition and in practice. Dissemination is a one-way process—to send information out widely, to publicize or broadcast information. This term was used specifically in the charge to the committee. However, the committee judged that to truly evaluate public understanding of health effects, as described in the MOU, it also had to look closely at the communication efforts of HHS agencies. Communication implies a two-way process—an interchange of knowledge, thoughts, and opinions or—as one dictionary puts it—communication is a back-and-forth process (Webster’s Third New International Dictionary 2003).

In keeping with its charge, the committee’s findings and recommendations are directed primarily at HHS activities. As noted earlier, the committee functioned under the public policy decision, reflected in the MOU, that to facilitate public understanding and acceptance of scientific findings related to health effects of hazardous exposures, responsibilities for operations and monitoring should be separated between two federal agencies, with DOE administering the nation’s nuclear activities and HHS monitoring, measuring, disseminating, and communicating information about worker and community health and safety is-

sues. In describing the events shaping the MOU, this report necessarily addresses previous concerns expressed about DOE’s management of these facilities and its actions in communicating the safety and health effects of radiation releases. This report however is not an assessment of DOE’s activities. The committee’s approach to this evaluation was shaped by a number of considerations, particularly the multiple and diverse ways in which individuals and communities process scientific information related to complex, often adversarial, scientific and technological issues.

COMMUNICATING ABOUT RADIATION RISKS

Communicating effectively about risks such as radiation health effects at DOE facilities to workers and concerned citizens is difficult for a number of reasons. First is the level of public fear about radiation from these sites. Although there is no uniform and consistent perception of radiation risk, research on the general public’s attitudes in the United States, Sweden, and Canada has shown that “public perception and acceptance is determined by the context in which radiation is used” (Slovic 2000). This means that although most people do not fear medical or dental X-rays because of the positive health value of these technologies, they do fear the radiation associated with nuclear weapons, nuclear power, and nuclear waste. Research using risk perception analysis in which different factors reflect how lay persons evaluate health and environmental risks on a number of characteristics has found that nuclear power and nuclear waste were rated as extreme in two dimensions: “dreaded” and “unknown” risks (Slovic 1987). Dreaded risks are catastrophic, deadly, and uncontrollable. Unknown risks are poorly understood, are unknown to those exposed, and have delayed effects. “Validation of these psychometric studies occurred when survey respondents were asked for word associations to a high-level radioactive waste repository. The resulting images were overwhelmingly negative, dominated by thoughts of death, destruction, pain, suffering and environmental damage” (Slovic et al. 1991).

Another finding from this research is that in every context of use, with the exception of nuclear weapons, public perceptions of radiation risk differ from the assessments of the majority of technical experts. In most instances, members of the public see far greater risks associated with a radiation technology than do experts (Slovic 2000). This disconnect between what the public and experts see as risks may lead experts to make little effort to understand what drives public fears and to dismiss these fears as trivial or “irrational.” A consequence of this disconnect is that communication efforts are frequently one-sided or unidirectional, reflecting the perspective of experts who want to communicate specific messages to the public rather than the view of what the public wants to know.

The second reason why communicating about radiation risks at DOE facilities is difficult is the complex documented history of secrecy at these sites (PSR

1992; Ackland 2002; Schneider 1988; NRC 1990). There is a history of hidden intentional and unintentional radiation releases potentially exposing both workers and citizens, producing serious public concerns about the motives and performance of DOE and its contractors and resulting in a loss of public trust and confidence in federal agency operations of these facilities. This loss of trust and confidence undermines acceptance since public confidence in information and in how well managers understand and control hazards and how trustworthy they are in fulfilling their protective duties is needed (Flynn et al. 2001). Again, the events leading to having three HHS agencies replace DOE as the performer of research on health effects and becoming the lead agencies in conducting research and communicating research findings and operations at DOE facilities were attempts to restore public confidence and trust in the operations of the federal government.

However, restoring or even establishing public trust is not easy. Trust in risk management assessments is difficult to achieve and maintain. It is usually created slowly but can be destroyed very quickly even by a single mistake. Once trust is lost, it may take a long time—if ever—to rebuild to its former state. “The fact that trust is easier to destroy than to create reflects certain fundamental mechanisms of human psychology that Slovic called the ‘asymmetry principle’” (Slovic 1993). According to this principle, when it comes to winning trust, the playing field is tilted toward distrust for several reasons. “First, negative (trust-destroying) events are more visible or noticeable than positive (trust-building) events. Negative events often take the form of specific, well-defined incidents such as accidents, lies, discoveries or errors or other mismanagement. Positive events, while sometimes visible, more often are fuzzy or indistinct. Second, negative events have much greater weight on people’s opinions than do positive events. Finally, sources of bad news tend to be seen as more credible than sources of good news by both people and the mass media” (Slovic 1993, cited in Kunreuther and Slovic 2001, p. 342).

A third reason why communicating about radiation risks at DOE sites is difficult is the complexity of the technical language and concepts. Radiation terms are foreign to most lay people and even seem contradictory at times (Friedman 1981; Friedman et al. 1987). In addition, when discussing possible radiation health effects, adding to the mix of rems, rads, and alpha or beta particles in radiation terminology is the language of epidemiology with its discussions of cohorts, case-control studies, and statistical power. Even well-intended glossaries often cannot help effectively translate this complex information or help lay people comprehend the concepts involved. More often than not, more can be accomplished in conveying such highly complex information in face-to-face situations where members of the public have the opportunity to ask questions about things they do not understand. This, however, can be a time-consuming and costly task and requires a special set of communication skills as well as specialized technical knowledge (NRC 1989).

Special Risk Communication Challenges for Federal Agencies

There are challenges beyond radiation risk and language that also have to be considered when trying to evaluate HHS dissemination and communication programs for DOE facilities. A fundamental conundrum for federal science agencies dealing with environmental risk controversies is that scientific and technical information alone seldom serves to resolve issues. The best-intentioned and most effectively considered and implemented communications programs encounter at least two major hurdles. First, environmental controversies are typically amalgams of scientific, political, economic, sociological, and ethical considerations. Second, provision of the “best” possible scientific and medical information may serve to lessen disagreement or forge consensus about “technical” aspects of the issue, but even if these goals are achieved, other dimensions of the issue may remain (Johnson 1999, as cited in Tuler et al. 2005).

More immediately germane to the challenges confronted by HHS agencies and DOE in organizing communication programs is that members of a community can have varying preferences about how they want such programs to be conducted and different criteria for determining the effectiveness or success of such programs. For example, a study of the attitudes and preferences of stakeholders living in the environs of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, California, discerned five different and, in some cases, competing perspectives (Tuler et al. 2005):

-

Evidence-driven process with good communication to the lay public. “This perspective describes a process that is about making recommendations based on a good understanding of the evidence about the nature of the problem and to effectively communicate with the community. In this perspective, the definition of the right problem should be locally determined.”

-

Efficiency and focus in a science-driven process. This perspective emphasizes “addressing the key problem in an efficient and well-run process…. The quality of information is important to those holding this perspective. The best available science should be used for analysis. Data must be evaluated to assess their quality for making public health determinations. Thus, it is important to identify weaknesses and gaps. At the same time, there was no support for exploring uncertainties in the data; doing so can lead the process astray.”

-

Meeting the needs of the community through accessibility and information sharing. This perspective places the concerns and needs of local people at the center while the needs and wishes of the responsible agencies are peripheral. It emphasizes generating and sharing information with the community. It places the highest value on tapping the knowledge of the community, ensuring that participants have equal access to information and that uncertainties are acknowledged and explored.

-

Ensuring accountability with broad involvement. “Those holding this per-

-

spective are interested in addressing and solving problems in a manner that ensures agency accountability and allows full involvement of the community. There is an underlying distrust of the motivations of the responsible agencies (e.g., DOE, ATSDR [Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry]) to redress public health risks that have arisen as a result of contamination released from the Laboratory” (italics added for emphasis).

-

Searching for the truth by thoroughly examining the evidence. This perspective emphasizes broad and informed discussion of the issue. “Information must be validated and it must be fully available for public discussion and consideration…. Those holding this perspective are interested in the truth of the matter.”

In effect, these perspectives point to stakeholder proclivities to employ different subjective frames of reference in responding to closed-ended scales of client satisfaction, thus reducing the value of conventional measures of program effectiveness. As noted by Tuler et al. (2005): “The core of our argument is that while generalized guidance about best practices can be useful, it can also be inadequate (and perhaps misleading) for a particular situation. Decisions about, for example, what risks to consider, how to compare and frame risks, and what are credible channels and sources of communication must be made in a process that meets social expectations about what is an appropriate process for the situation. The effectiveness of the risk communication effort may rest, in part, on meeting social preferences for how the process of planning and decision-making is designed.”

General Risk Communication Guidelines

As described above, each site and different stakeholders involved at that site have their own ideas, preferences, needs, and problems regarding the risks present or anticipated. Developing an environmental or health risk communication program to meet all of these needs is a complex process that requires considerable levels of commitment, time, money, and personnel on the part of government agencies. However, federal agencies do not enter this difficult territory without some general guidelines derived from a more than 30-year history of research and practice in the field of risk communication.

According to leading risk communication researchers, good risk communication is “communication intended to supply laypeople with the information they need to make informed independent judgments about risks to health, safety and the environment” (Morgan et al. 2002). As described in a National Research Council (NRC 1989) report that addressed the challenges of risk communication: “Risk messages should closely reflect the perspectives, technical capacity, and concerns of the target audience. A message should: (1) emphasize information relevant to any practical actions that individuals can take; (2) be couched in clear

and plain language; (3) respect the audience and its concerns; and (4) seek to inform the recipient, unless conditions clearly warrant the use of influencing techniques.”

Effective communication should focus on the issues that recipients most need to understand. Which issues need to be understood should be determined by both the communicator and the recipient. Risk researchers caution that if a communication omits critical information, it leaves the recipients worse off because it could make them believe that the information they have is complete. If it presents irrelevant information, it wastes recipients’ time and diverts their attention from more important tasks (Morgan et al. 2002).

Effective risk communication also requires authoritative and trustworthy sources. If communicators are perceived as having a vested interest, then recipients could doubt the truth of the information communicated. This lack of trust makes the communication process far more complex, spreading confusion and suspicion and thereby eroding relationships.

Finally, for a risk communication effort to succeed, the developers of the communication program must ensure that their messages are being understood as intended. Failing to evaluate whether risk messages have been understood or whether a risk program has been effective is a major problem because everyone involved in the process could be miscommunicating or talking past each other and yet no one knows it. When a message is not understood, the recipients, rather than the message, may be blamed for the communication failure. However, if “technical experts view the public as obtuse, ignorant, or hysterical, the public will pick up on the disrespect, further complicating the communication process” (Morgan et al. 2002). Lack of evaluation wastes both communicators’ and recipients’ valuable time as well as the resources spent in developing and providing the risk communication efforts.

No matter how good a risk communication program looks to its designers, it will be discounted if it is only a one-way dissemination system in which information is given to workers and citizens with no room for their opinions. Using, at the minimum, a two-way risk decision-making process that includes both citizens’ and workers’ concerns has been increasingly recommended and implemented. For example, in its final report, the Presidential/Congressional Commission on Risk Assessment and Risk Management (1997) concluded that a good risk management decision emerges from a process that elicits the views of those affected by the decision, so that differing technical assessments, public values, knowledge, and perceptions are considered. The Presidential/Congressional Commission on Risk Assessment and Risk Management (1997) referred to those affected by a risk or a risk management decision as stakeholders, stating:

“Stakeholders bring to the table important information, knowledge, expertise, and insights for crafting workable solutions. Stakeholders are more likely to accept and implement a risk management decision they have participated in shaping. Stakeholder collaboration is particularly important for risk management

because there are many conflicting interpretations about the nature and significance of risks. Collaboration provides opportunities to bridge gaps in understanding, language, values, and perceptions. It facilitates an exchange of information and ideas that is essential for enabling all parties to make informed decisions about reducing risks” (Presidential/Congressional Commission on Risk Assessment and Risk Management 1997).

An important guideline from an NRC (1989) report also bears directly on the committee’s review of HHS’s communications activities: “Risk communication is successful only to the extent that it raises the level of understanding of relevant issues or actions and satisfies those involved that they are adequately informed within the limits of available knowledge.” All of the guidelines mentioned for effective risk communication in this introduction, taking into consideration the considerable challenges involved, were used to evaluate HHS dissemination and communication efforts to workers and citizens.

COMMITTEE’S APPROACH TO EVALUATING THE HHS EFFORTS

To evaluate HHS’s dissemination and communication efforts under the MOU, the committee reviewed information provided by HHS agencies to the affected communities in terms of relevance, accuracy, accessibility, timeliness, comprehensibility, and credibility. For its evaluation, the committee reviewed a sample of written, electronic, and oral communications of the HHS health study findings and other outreach efforts at three sites: Hanford, Oak Ridge, and Los Alamos. These site-specific reviews are described in detail in Annexes 5A, 5B, and 5C, respectively.

Beyond looking at specific efforts, the committee also contacted selected members of the Hanford Advisory Board and others in that region to get their input about the impact of the dissemination and communications efforts on this community. It also solicited information from social scientists who had studied some of the government-public interactions at DOE sites and sought the views of former members of several site-specific committees as well as other knowledgeable individuals. In addition, the committee ran searches in the Lexis-Nexis academic database to identify key public and worker issues that appeared in newspapers at each of the three sites and whether these had been addressed by HHS risk communication efforts. It also searched the Lexis database specifically to see whether information disseminated by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) to workers and the public about various studies had reached a wider audience through newspaper coverage. Finally, to ensure that it had as complete a picture as possible, the committee reviewed NIOSH media coverage in a large collection of articles in the evidence package presented by the agency.

AGENCY COMMUNICATION EFFORTS

The three HHS agencies involved in this study had a number of dissemination and communication responsibilities. NIOSH, through its Office of Occupational Energy Research Program (OERP) and its Health-Related Energy Research Branch (HERB), was responsible for communicating its study findings to workers, the public, Native American tribes, the scientific community, and other stakeholders. The National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH) provided information about its studies to workers and the public primarily through its contractors. Several NCEH contractors, including the Technical Steering Committee for the Hanford Environmental Dose Reconstruction (HEDR) and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center for the Hanford Thyroid Disease Study (HTDS), undertook considerable public communication efforts. Of the three HHS agencies, the ATSDR is the most heavily involved in conducting communication, outreach, and education efforts for the general public in the communities surrounding DOE facilities. As part of its broad congressional mandate to evaluate public health concerns related to exposures at hazardous waste sites, ATSDR developed and provided information, education, and training concerning hazardous substances to affected communities across the country, including but not limited to DOE facilities.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

NIOSH is responsible for conducting epidemiological studies of workers at DOE facilities and for communicating the findings to workers and their representatives and to the community at large. The OERP has a number of communication goals related to effectively informing workers, scientists, and the public about its work. These goals include the following (NIOSH 2005):

-

“Develop better mechanisms for generating research hypotheses by expanding the involvement of partners and actively seeking their input.”

-

“Conduct research in an open environment with attention to clear and accurate education of workers and the public.”

-

“Provide information that enhances the understanding of risks associated with radiation-induced health effects.”

-

“Solicit and consider worker interests and the public’s concerns.”

-

“Provide relevant occupational exposure and health outcome information for public health research and policy.”

NIOSH communication activities include establishing communication plans and channels for the various sites, providing simultaneous communication to management and labor representatives, distributing one-page Brief Reports of Findings, making final technical reports available, and interacting directly with

workers. NIOSH conducted a needs assessment of what workers wanted to see in summaries of research findings, including simplified definitions of technical terms, other language-level issues, and increased availability of information (Ahrenholz 2001).

According to NIOSH, the main mechanisms for OERP and HERB communication efforts include the following (NIOSH 2005):

-

Regular research meetings. These meetings allow researchers (primarily those funded extramurally) to have an opportunity to communicate about their research.

-

Periodic conference calls and on-site meetings with affected workers to discuss study status and results. Slide shows and other presentations are given at these meetings for workers, providing an update on findings of studies that had been completed, the studies that are currently under way, and occasionally reminding viewers about the MOU, its various governmental links, and the responsibilities of NIOSH under the MOU (NIOSH 2006b). NIOSH made presentations to both the Hanford and the Oak Ridge Health Effects Subcommittees, including slide shows and other briefing materials (NIOSH 2006b).

-

Brief Reports of Findings issued to workers through the mail, electronically, and on-site. These one- or two-page summaries are discussed in more detail below.

-

Public meetings. Occasionally, NIOSH has convened a public meeting such as the one about its epidemiological research program conducted under the MOU in Washington, DC, on October 27, 2005 (NIOSH 2006a). It also has a plan to provide study results to individual workers but has not used it. The 1988 NIOSH Worker Notification Procedures Manual details how these results are to be reported; however, NIOSH has stated that “to date, researchers have not had a study finding that necessitated formal individual worker notification” (NIOSH 2005).

NIOSH Brief Reports of Findings

NIOSH places significant emphasis on the use of short reports of study findings to communicate about research and activities to workers and the general public. These reports have various titles, including “Brief Reports of Findings,” “Announcement of Findings,” or “Summary of Findings.” The Brief Reports typically have included information on the type of study conducted, its purpose, a description of the study population, the study methodology, the main study findings and conclusions, limitations of the study, a glossary of terms, and information about how to obtain a copy of the full study and to reach a contact person for addressing questions (NIOSH 2005). According to NIOSH (NIOSH 2005), these reports were prepared after extensive consultation with workers and management at DOE facilities. The report summaries were converted to a conven-

tional file format (portable document file or pdf) so that they could easily be placed in site newsletters, on bulletin boards, and on web sites. They were also distributed directly to individual workers or to worker representatives as an e-mail attachment. While NIOSH did not require extramural researchers to engage in communications activities, information about a number of their studies was disseminated through these reports.

NIOSH frequently provided the same information to various DOE facilities with these reports, using different “editions,” such as the Hanford or Oak Ridge edition. This was particularly true if the study was one that involved multiple sites. It also occasionally issued NIOSH-HERB updates, which related information about two or three main studies that were being conducted at a particular site and also included very brief descriptions of other studies going on at the site. Several updates were evaluated for Hanford, Oak Ridge, and Los Alamos: these usually contained the same basic information for all sites but were tailored to highlight information from the viewpoint of a particular site.

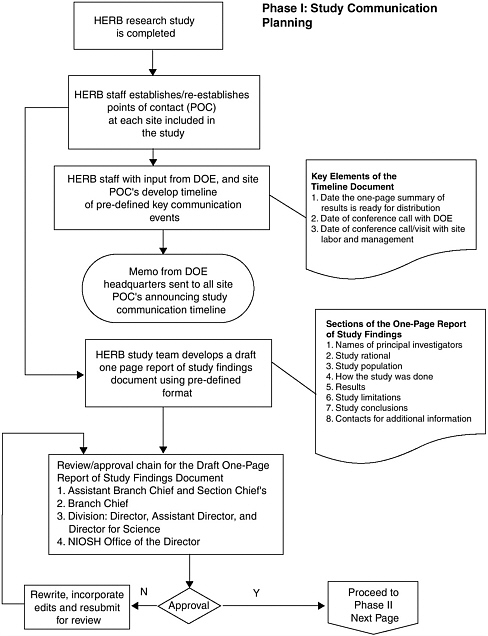

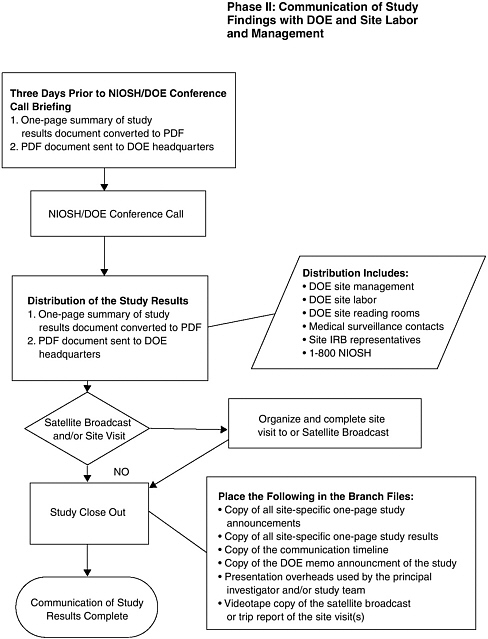

When a study was completed under the OERP, study findings were reported to workers, DOE Headquarters, site managers, and site contractor management. Initially, study results were communicated to workers and worker representatives simultaneously. However, because of concerns expressed by DOE, the procedure was changed and findings were communicated to DOE Headquarters three days before the communication to workers and site management. All of this resulted in a complex communication and clearance procedure, which is diagrammed in Figures 5-1 and 5-2 (see NIOSH 2005).

Agency Communication Evaluation

NIOSH states that these reports have been used to “successfully communicate the findings of approximately thirty internal and external studies to some 300,000 current and former DOE workers” (NIOSH 2005). The basis for this assessment that findings have been “successfully” communicated, however, is not documented in NIOSH reports. It appears to relate to estimates of the number of individuals “reached” by NIOSH activities, rather than to any systematic study or assessment from target audiences about the relevance, quality, and timeliness of the information. NIOSH reports also a lack of evidence about whether or how the information was used or the degree to which this information produced increased agreement within the affected community about any specific scientific or technical aspect of the subject matter under study.

According to NIOSH, there were no external evaluations of its outreach program. Instead, there were internal evaluations by its communications team, which consisted of the assistant branch chief, a health communication specialist, and one or more service fellows. Scientific and technical staff and others at NIOSH with health communications expertise assisted as needed. NIOSH states that “the success of the OERP communication strategies was evaluated periodi-

cally by obtaining feedback (primarily verbal) from workers and management on the effectiveness of the communications channels and instruments (e.g., the ‘Brief Reports of Findings’) and adjustments were continuously made to accommodate this feedback, to make the process and information more useful to the target audience.” All formal communications to worker representatives, including the Brief Reports, were reviewed and edited by the NIOSH public information office, whose personnel also provided feedback to OERP on ways to better involve workers and the public in its activities (NIOSH 2006c).

Committee Evaluation of NIOSH Efforts

Despite these evaluation procedures and NIOSH’s early concern with target audience needs for simple language in these Brief Reports of Findings, the committee judged that much of the language in these reports was quite technical and would not be easily understandable to readers with a high school education, even though the readers might have had some technical training. The glossaries, which were provided to help comprehension, also were technical and difficult to understand. A Ph.D. social scientist with no radiation background, who also is a technical editor, read one Announcement of Findings on “Epidemiological Evaluation of Cancer and Occupational Exposures at the Rocky Flats Environmental Technology Site” (April 2003)1 and verbally told an NRC committee member that he thought the main parts of the report and the glossaries were not well written and would not be understood easily by lay readers. He did not consider the glossaries any help to people who were not familiar with the study or radiation terms.

Based on its own review, the committee concurs with these comments, which apply to almost all of the Brief Reports of Findings. It questions whether many workers, their families, or their representatives such as union officials would be able to understand the information conveyed. Unfortunately, this assessment also extends to many of the slide show presentations viewed in the NIOSH evidence package (although one would expect that the presenters would have made special efforts to describe and explain the material being presented orally) (see NIOSH 2005). These materials appear to be written at a level that was too difficult for easy comprehension by a lay audience. One example of the use of such complex language can be found in a 2002 NIOSH Announcement of Findings— “Lung Fibrosis in Plutonium Workers.” The brief report states the following: “There was a significantly higher proportion of abnormal chest radiographs among plutonium workers (17.5%) as compared to non-plutonium workers (7.2%), p = <0.01. The plutonium workers were significantly older at time of x-ray than were unexposed workers, possibly accounting for the differences. Of those plutonium

|

1 |

See http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/oerp/pdfs/2001-133g26-1.pdf. Last accessed November 2006. |

workers with absorbed lung doses of 10 Sv or greater, 37.5% had an abnormal chest x-ray, compared to other plutonium workers (16.5%). When we controlled for effects of age, smoking, and asbestos exposure we found that plutonium lung dose of 10 Sv or greater conferred a 5.3-fold risk of having an abnormal chest x-ray when compared to employees with no plutonium exposure (95%C.I. = 1.2 to 23.4).” It is not clear to the committee why these language problems did not surface during OERP personnel contacts and meetings with workers and through other internal evaluation procedures.

As documented in more detail later in the Hanford case study, individuals attentive to worker health issues reported that NIOSH did in fact go beyond the dissemination of documents. While those who commented on this issue uniformly reported that NIOSH did not appear to have consulted with workers or their representatives in the selection of research topics on study design, once NIOSH launched a study, in addition to disseminating information in print, it routinely met with labor groups and kept them well informed as to the progress of the study, as well as the final results. Of the 13 individuals who were contacted as a part of the Hanford case study, only a few indicated that they were generally familiar enough with the activities of all three HHS agencies to offer any observations on their comparative effectiveness. However, these few judged NIOSH to be the most effective in its dissemination activities.

The lack of any external evaluation of NIOSH dissemination and communication efforts handicaps an evaluation process by the committee. Written materials and records provided by NIOSH relating the success of meetings and other communication methods such as slide shows employed by NIOSH to communicate with workers and members of the public about its studies are all based on agency activities and perspectives; they do not provide information or data on how stakeholders responded to these activities, and thus do not provide an adequate basis for a third-party assessment.

Other Communication Efforts to Workers

Newspapers The NIOSH Brief Reports were the likely basis for some newspaper articles that appeared about NIOSH studies. In a two-stage communication process, these articles served to disseminate NIOSH reports to workers and members of the public in a more understandable form. Newspaper articles using lay language were written about at least six of these studies. The largest number of newspaper articles found during the committee’s search of Lexis-Nexis covered the Rocky Flats study discussed previously, with slightly different interpretations of the study findings.2 The Associated Press wire service ran a story emphasizing

that the 10-year study “found workers who dealt with plutonium were about two times more likely to develop lung cancer than those who were not employed at the plant” (Long 2003). The Denver Post emphasized that most Rocky Flats workers are typically healthier than the general public, but some types of cancer are higher for workers (Nicholson 2003). It pointed out that the study did find “a significant risk of lung cancer for weapons workers who inhaled radioactive particles.” The Rocky Mountain News emphasized that “people who inhale plutonium have a higher risk of lung cancer than previously believed, according to a study of Rocky Flats workers” (Morson 2003).

The details in these news articles encompassed more than those presented in the Rocky Flats Brief Report of Findings, suggesting that reporters obtained additional information. One such source was the study director, who is quoted in the articles, along with state and NIOSH officials and one worker. One article indicated that the report was released at a public meeting (Nicholson 2003). Neither the technical language nor anything from the glossary in the Brief Report of Findings appeared in the newspaper articles, as one would expect.

Other newspaper or wire articles that appeared about NIOSH studies included the following:

-

Epidemiological Evaluation of Childhood Leukemia and Paternal Exposure to Ionizing Radiation, September 1998.3 This was a very brief article by Associated Press that represented information in the NIOSH report (Associated Press 1998).

-

Multiple Myeloma Case-Control Study at the Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion Plant (K-25), March 2000.4 Noted in a NIOSH-HERB Oak Ridge Update, this study was described by Associated Press as relating specifically to Los Alamos although it did mention that other sites also were involved (Associated Press 2000). An article in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer discussed the implications of the research for Hanford (Paulson 2000). Both articles emphasized the increased deaths from multiple myeloma, but the Associated Press article discussed the increased sensitivity to radiation of older workers in more detail and earlier in the story than did the Seattle article.

-

Mortality Among Female Nuclear Weapons Workers, June 2000;5 Associated Press wire service. This article noted that the study director would discuss his findings from Washington, DC, in a live satellite presentation and that this presentation would be videotaped and made available at sites involved in the

-

study. This article accurately summarized the main points of the NIOSH Brief Report of Findings (Hebert 2000).

-

Epidemiological Study of Mortality and Radiation-Related Risk of Cancer Among Workers at the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory, a DOE Facility, October 2004.6 An article in the Idaho Falls Post Register reflected the main findings of the study but also included other information, including comments from one worker (O’Neil 2004).

-

Cancer Risk Following Low Doses of Ionizing Radiation—A 15-Country study7 (no date). No U.S. articles were found, but one article about the study appeared in the Irish Times and one in the Guardian, both UK publications, on June 29, 2005. The Guardian article represented well the information about the study (Boseley 2005), while the Irish Times article went into areas not covered in the NIOSH Brief Report and summarized only its main points (Ahlstrom 2005).

While these newspaper articles did not cover all of the NIOSH studies done at the sites, the newspapers selected a few important ones to present to their target audiences in an understandable and generally accurate manner. These efforts extended the reach of NIOSH information from some of the Brief Reports of Findings.

DOE Communications In the 1990s, DOE provided information to workers about studies, including some by NIOSH, in several different ways. DOE reported on the following studies in Health Bulletins:

-

Mortality Among Workers Exposed to External Ionizing Radiation at a Nuclear Facility in Ohio. This study was done by Los Alamos scientists and published in a journal in May 1991. This study focused on the Mound Facility near Dayton. There also was a brief discussion of another Mound study for polonium-210 exposure.

-

Epidemiological Study at Oak Ridge. This study followed up a previous mortality study in 1985. This referenced a study by Dr. Steven Wing and presented results in 1991 of an apparent association between very-long-term, low-

-

level radiation exposure and an increased risk of death from all types of cancer combined.

-

Worker Mortality Study at Los Alamos National Laboratory. This study was published in a journal in 1994.

-

Uranium Dust Exposure and Lung Cancer Risk in Four Uranium Processing Operations. This study explored the risk of lung cancer in workers who had inhaled uranium dust at three sites. The study was published in a journal in 1995.

-

Y-12 Worker Mortality Study. This was conducted by the University of North Carolina in 1996.

-

Mallinkrodt Chemical Works Mortality Study. This was also the subject of a newspaper article in the Cincinnati Enquirer. Results were presented to workers at Mallinckrodt in 1998.

-

Multiple Myeloma Study at Four Sites. Results of this study by Steven Wing were presented in 1998 to workers at the four study facilities and published in April 2000 in a journal.

-

NIOSH Study of Parents’ Exposure to Ionizing Radiation and Cancer Among Their Children. This study was presented to workers in 1998 at each of the three DOE facilities involved.

-

Mortality Study of Rocketdyne-Atomics International Workers for Exposure to Both Radiation and Asbestos. These studies were presented to workers and community members soon after completion of each study and portions were published in journals in 1999.

DOE also published two issues of Health Watch in 1993, which discussed various rules and standards for workers, and two issues of Epidemiology News, which summarized various worker studies. It also published a paper called “Description of CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] Studies,” which summarized various NIOSH studies of the health of workers at individual DOE facilities and mentioned other NIOSH studies, including community studies near DOE facilities by NCEH and a study at multiple sites of maternal and paternal pre-conception exposure to ionizing radiation and childhood leukemia. Except for similar headings, no standardized format was used in these DOE documents as was later done with the NIOSH Brief Reports of Findings. There were no glossaries either. A number of the documents noted that results were reported directly to workers with a date, included information about publication of the research findings in journals, and had a standard line that information from the study was “provided to committees that review and make recommendations regarding radiation health protection standards in the United States.” There was always a contact person’s name and phone number on these bulletins. The committee judged that some of the writing in these DOE Health Bulletins was clearer and less technical than that in the NIOSH Brief Reports, although these still might have been difficult for lay persons to understand.

National Center for Environmental Health

NCEH studies the “health effects of environmental radiation exposures from nuclear weapons production facilities in the United States” (NCEH 2006a). It is responsible for conducting research on ionizing radiation in the environment.8 NCEH conducts dose reconstruction and other health studies at DOE facilities. Regarding communication and outreach efforts, NCEH chose to communicate much of its work through the Health Effects Subcommittee (discussed below). “NCEH’s goal was to keep the public informed through meeting notifications (by contractor mail-outs) to interested individuals and organization and by posting meeting announcements in the Federal Register” (NCEH 2006c).

NCEH noted that there were dedicated subgroups of the Health Effects Subcommittees (HESs) at Fernald, Hanford, Idaho National Laboratory, and the Savannah River site that worked to evaluate the agency’s communication and outreach activities. Also, NCEH used the HES and local community meetings to “help develop effective communication of project research and findings” (NCEH 2006c).

NCEH provided a list of documents that were in storage in boxes but in principle available to the committee upon request (NCEH/ATSDR 2006). Due to time constraints, the committee was not able to review many documents that were included in this list. Instead, the committee chose to review the communications efforts related to larger-scale NCEH projects, including HEDR at the Hanford site and the Los Alamos Historical Document Retrieval and Assessment (LAHDRA) at Los Alamos.

Hanford Environmental Dose Reconstruction Project

Two major projects were conducted by NCEH at the Hanford site. The first was the HEDR Project. The HEDR was initiated to estimate the amount and type of radiation releases to which individuals living at or near the Hanford site may have been exposed during the production of nuclear materials. The purpose of the study was to “address community health concerns by estimating the amount and types of radioactive materials that were released to the environment (via air and river pathways) from the Hanford Site and by estimating radiation doses to representative individuals within the communities downwind from Hanford” (NCEH 2005) (see Chapter 4).

Although this project was inherited by NCEH from DOE, it was still funded in part by NCEH under the MOU for several years and is considered within the purview of the committee’s study. Originally, DOE directed Battelle Pacific Northwest Laboratories, one of its contractors, to conduct the HEDR. However, this action did not satisfy a distrustful public, and DOE agreed with Washington

and Oregon that an independent group needed to direct the study and provide a forum for participation and direction by the states, Native American tribes, and the public. In 1988, a Technical Steering Panel (TSP) was selected to direct the work. Its members were chosen by the deans of research at major universities in the two states. The states and involved Indian tribes also had representatives on the TSP (Niles 1996).

Besides handling the scientific aspects of the HEDR Project, the TSP developed important public communication plans. Interestingly, the desire to provide resources for public information caused an early “internal battle”: some members of the TSP were not convinced of the importance of public communication, and some wanted to reserve funds only for scientific research. However, the need for public information eventually was recognized and a subcommittee of the TSP was established to address it. Initial communication efforts focused on dissemination, specifically “establishing and building mailing lists, providing meeting summaries to the public, preparing and sending out meeting notices, drafting a public information plan, and preparing fact sheets that explained the Project work” (Niles 1996). Staff support for the TSP’s communication program came from the Washington State Department of Ecology and the Oregon State Department of Energy (Niles 1996). Meeting monthly, the TSP Communications Subcommittee used information gathered in surveys, focus groups, and comment forms to develop annual communication plans and budgets. The TSP used the following tools to support its public information program (Niles 1996):

-

A quarterly newsletter;

-

Fact sheets written by TSP members on a variety of topics—the TSP produced 18 fact sheets and distributed about 100,000 copies of them;

-

Two informational videos explaining how and when radiation releases occurred at Hanford, among other things—more than 300 copies of each were distributed to libraries, hospitals, schools, and community groups throughout the Northwest;

-

A poster for use in libraries and meeting places to introduce people to HEDR;

-

Public meetings in conjunction with each TSP meeting;

-

A question-and-answer brochure;

-

A speakers’ bureau whose members spoke to civic groups, the medical community, scientific groups, schools, and others;

-

Quarterly and annual reports to keep interested parties updated on TSP work: the Communications Subcommittee provided quarterly reports to ensure that the TSP and the public were aware of ongoing public information activities; according to the TSP, public reaction to this approach was good;

-

Newspaper advertising for TSP and community meetings to encourage public attendance;

-

Reports of major HEDR accomplishments, including short summaries written for the media and the public;

-

Direct mail to keep people informed of ongoing meetings and other activities, sent to more than 6,000 citizens and the region’s media;

-

News releases sent to more than 100 media organizations;

-

A toll-free phone line for free and easy access to project information— about 9,000 calls were received from people requesting information or asking questions; and

-

Document repositories at 13 public libraries throughout the region.

Agency Communication Evaluation

According to the “History of the TSP,” evaluation of its communication materials and program as a whole was a major part of this project (Niles 1996). First, its initial communication plan was developed with input from focus groups on target audience needs for information. Many of its “communication products were reviewed by Downwinder groups and other interested members of the public while still in draft form. This allowed those with a personal interest in the Project to help ensure the written materials were clear and unbiased” (Niles 1996). TSP members believed that these review efforts resulted in better communication products. In 1991, the TSP sponsored a telephone survey by Washington State University to determine citizen attitudes, opinions, and level of knowledge about the project. Overall findings showed that people were interested in the project, that the public information efforts were well targeted, and that the TSP needed to continue to communicate with the public in a variety of ways, including producing fact sheets and newsletters, although the news media proved to be the most effective sources of public information about the project (Niles 1996).

Major efforts also were made to provide clear information for the public when major project announcements were being made. Months of careful planning went into preparing for each announcement at well-attended public meetings in a number of cities in Oregon and Washington, according to the TSP.

The Hanford Thyroid Disease Study Project

The second major NCEH project at Hanford was the HTDS. A similar public information effort was carried out for the HTDS by the Fred Hutchison Cancer Research Center, a CDC contractor in Seattle (see Chapter 4). However, that study is not a topic of this report since it was specifically ordered by Congress. It should be noted that this contractor developed an excellent public information program that ran for 9 years with input from a number of stakeholder groups; many of its elements can be considered best practices. Unfortunately, at the end of the study, some communication problems occurred to mar the record of this otherwise fine program (NRC 2000; Friedman 2001).

Committee Evaluation of NCEH and Contractor Dissemination and Communication Efforts

Details about this public information effort are included in this report not only because the HEDR Project came under NCEH purview in its later stages, but also because it serves as a good example of a concerted effort to communicate with the public. In all, in the committee’s view this serves as one of the best examples of best-practice communication techniques encountered in its review of HHS activities. As reviewed by the committee, communication products distributed to the public through this program were understandable, timely, and informative. Large mailing lists and the use of commercial media helped to ensure that the communication messages reached a large regional audience. Some two-way communication also occurred, according to the TSP History, with early input from focus groups on the initial HEDR communication plan and through consultation about and review of communication products still in draft form by Downwinder groups and other interested parties. Finally, this program used various evaluation techniques to make sure that its messages met the needs of the target audience, were understood, and reached the intended audiences. Such evaluation efforts are laudable and speak well for the HEDR communication program.

Comparing the HEDR and HTDS public communication efforts to those used by NIOSH, NCEH for other sites, and ATSDR indicates that these HHS agencies have followed different models and mechanisms for public and worker communication. Based on the information the committee has reviewed, the models used by both the HEDR and the HTDS contractors worked quite well. This observation brings up the question of what organizational arrangements and levels of commitment are needed for effective communication, which are commented on in the discussion, conclusions, and recommendations at the end of this chapter.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

ATSDR is congressionally mandated to evaluate public health concerns related to exposures at hazardous waste sites. A significant part of these efforts includes “information development and dissemination, and education and training concerning hazardous substances” (ATSDR 2006a).

Of the three HHS agencies, ATSDR is the most heavily involved in conducting communication, outreach, and education efforts for the communities surrounding DOE facilities. In 2000, the MOU between the HHS and DOE cited ATSDR’s responsibilities:

-

Preparing Public Health Assessments (PHAs) and health consultations for the communities. PHAs are “in-depth evaluations of data and information on the release of hazardous substances into the environment.” The public is encour-

-

aged to comment on the PHAs during a 45-day public comment period (ATSDR 2006b). ATSDR also prepared press releases and newspaper advertisements announcing that the PHAs were available for public comment (ATSDR 2006b) (see Chapter 3). The PHAs include information on estimated exposure levels (doses) that may be experienced by individuals in the vicinity of the DOE sites.

-

Engaging in health education and promotion activities by developing and implementing strategies to promote health and reduce potential exposures and disease. Because of its responsibilities under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), ATSDR has often taken the lead in communication and outreach efforts to the affected populations surrounding DOE facilities. Some methods of written communication include news releases, press advisories, letters to the editor, site-specific web pages, public service announcements, and media interviews (ATSDR 2006b).

-

Conducting site-specific health surveillance, health studies, and exposure and disease registries. Health surveillance efforts are used to screen the affected population for biological markers of disease, while health studies use biomarkers to study health effects related to exposure to low levels of toxicants. The National Exposure Registry, which includes data from specific subregistries, is “designed to communicate to individuals the best available information to the long-term health consequences of low-level, long-term exposures to hazardous chemicals identified at hazardous waste sites.”9

-

Developing toxicological profiles at the site. ATSDR is congressionally mandated to develop toxicological profiles for environmental contaminants present at Superfund sites. The profiles are designed to “succinctly characterize the toxicologic and adverse health effects information for the hazardous substance.”10 ATSDR produced seven toxicological profiles on radioisotopes under the MOU for americium, cesium, cobalt, iodine, ionizing radiation, strontium, and uranium. An evaluation of these profiles can be found in the scientific program assessment (Chapter 3).

Public Health Assessments

ATSDR prepared separate PHAs for four areas at Hanford: the 100-, 200-, 300-, and 1100-Areas. The agency also prepared five PHAs for Oak Ridge and one for Los Alamos. Each of these followed a similar format, with brief summaries, followed by sections on background of the site and the area being studied; community and Native American health concerns; environmental contamination and other hazards; pathway analysis; public health implications; conclusions; and

|

9 |

2000 Memorandum of Understanding between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. |

|

10 |

See http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxpro2.html. Last accessed August 2006. |

recommendations. For the Hanford PHA on the 200-Area, a public health plan was also included at the end of the report. In final versions of the PHAs, public comments were included in tabular form with agency responses. The three Hanford documents viewed by the committee were relatively brief and understandable in the summary, conclusions, recommendations, and sections related to community health concerns and public health implications. The scientific discussion sections, as expected, were more difficult for the public to comprehend.

One of the PHAs on the 300-Area at Hanford described how ATSDR attempted to find out about community health concerns by distributing flyers to more than 1,000 Hanford residents. It received 93 replies and made 12 additional telephone calls in response to requests for oral responses. In addition to the flyers, ATSDR staff and scientists exchanged communications with representatives of the nine tribal nations in the area (ATSDR 1997b). Perhaps due to the low response rate to its flyers or other unknown factors, the discussions of community health concerns in the Hanford PHAs appear to be formulaic. For example, similar paragraphs are repeated in different reports. Some of this could be attributed to a conventional “front-end boilerplate” approach, but other aspects involving substantive sections of the reports also appeared forced into a standard pattern that curtailed more explanatory and less technical information about site-specific findings.

A later PHA for the Y-12 uranium releases at Oak Ridge Reservation, issued on July 30, 2004, showed improvement in quantity and quality over the Hanford reports (ATSDR 2004c). All sections of the PHA were more developed, particularly the public health implications and community health concerns. A new section had been added about children’s health considerations; a public health action plan was also part of the PHA. The summary section had several blocks of print that either highlighted the major finding of the PHA or explained technical information to readers. This report had 16 pages of tabular public comments and responses, although many of the responses were not very informative.

Toxicological Profiles and Tox FAQs

When a draft toxicological profile is released, the public has 90 days to comment. After the comment period has ended, ATSDR states that it “considers incorporating all comments into the documents” and finalizes the profiles, which are then available on the Internet and through the National Technical Information Service. Copies also are sent to state health and environmental agencies and other interested parties.11

The first chapter of a toxicological profile is directed at the public. Called the Public Health Statement (PHS), it provides a summary of the toxicological profile in understandable language and is prepared as a series of questions. For example, in the profile on americium, topics include (ATSDR 2004b) the following: What is americium? What happens to americium when it enters the environ-

ment? How might I be exposed to americium? How can americium enter and leave my body? How can americium affect my health? How can americium affect children? How can families reduce the risk of exposure to americium? Is there a medical test to determine whether I have been exposed to americium? What recommendations has the federal government made to protect human health? Where can I get more information? The PHS is available as a stand-alone document in both English and Spanish. The toxicological profiles also include a “Quick Reference for Health Care Providers,” which describes the chapters of the profiles and refers to information that might be relevant to a health care provider, including the sections related to pediatrics and child health issues.

In addition to the toxicological profiles, ATSDR produces ToxFAQs, brief two-page fact sheets with information about a substance, available in both English and Spanish. The sections of the ToxFAQs closely mirror those of the PHS, but the text is reduced and simplified substantially. The documents also include a box of highlights summarizing the main findings in the toxicological profile. For example, the highlights section of the americium document states: “Very low levels of americium occur in air, water, soil, and food, as well as in smoke detectors. Exposure to radioactive americium may result in increased cancer risk. Americium has been found in at least 8 of the 1,636 National Priorities List (NPL) sites identified by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)” (ASTDR 2004b).

Agency Communication Evaluation

To evaluate the communication quality of its documents, in addition to requesting public comment, ATSDR included surveys approved by the Office of Management and Budget with each PHA and health consultation to request public input. Of the 2,214 surveys distributed, 82 completed surveys were returned to ATSDR, resulting in a rate of return of 3.7 percent. ATSDR reported that the “affirmative response rate of community members regarding whether their health concerns were addressed in ATSDR documents increased from 65 percent in FY2003 to 78 percent in FY2004.” Of the responses received on surveys of PHAs and health consultations, the public was generally pleased: the questions were answered 81 percent positively, 13 percent negatively, and 6 percent with no opinion. One question on the survey (Were the customers’ health concerns addressed?) received 78 percent positive replies, 16 percent negative replies, and 6 percent no opinion. ATSDR used three other survey tools in FY 2004 to obtain public feedback including the following: “3,612 community health concerns surveys mailed out to communities resulted in an 11% return; distribution of 298 community meeting surveys at the meetings resulted in a return rate of 46%; and

|

11 |

See http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxpro2.html. Last accessed August 2006. |

distribution of 9,363 fact sheets surveys resulted in a 7.0% return.” (ATSDR/ NCEH 2006). The community meeting survey had the highest response rate and the response rate for the community health concerns and fact sheet surveys were two to three times higher than those for PHAs and the health consultations (ATSDR/NCEH 2006).

Committee Evaluation of ATSDR Efforts

In general, based on its examination of the communications sections of the four PHAs discussed above, the committee believes that ATSDR made an effort to make sections of these reports understandable to interested members of the public and to address their concerns in these reports. Most of the sections of the PHAs that members of the public would be interested in and would have read were written in language that would be understandable for a general audience.

In general, the ToxFAQs were condensed to a reasonable length, were relatively easy to read, and translated the health information into understandable language. Since the documents were not site-specific, they did not include information about potential exposure scenarios at the sites. The format followed that of the PHS and included a number of questions about which those living near the sites might be interested in learning more, including questions about childhood exposures and how families could reduce exposure.

Generally, ATSDR appears to have fulfilled its requirements to disseminate information to citizens living near DOE facilities. Its web site has many items and links, conveying and explaining information to interested readers about health issues at these sites. Although the percentage returns from the public on some of its evaluative efforts were low, it appears that the agency did make a concerted effort to obtain public input and feedback to improve its efforts. Some specific programs and issues related to ATSDR efforts are discussed later in the site-specific sections of the annexes to this chapter.

AGENCY COMMUNICATION EFFORTS WITH ADVISORY COMMITTEES

Advisory committees also played an important role in communicating and disseminating information about health risks to the public at or near the DOE sites. Some such committees are discussed below.

Health Effects Subcommittees

Health Effects Subcommittees were established at some DOE facilities as a major way to establish two-way communication and allow for public input and advice on decision making. These were established under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) “to provide advice to CDC and ATSDR about public

health and research activities conducted by CDC and ATSDR at DOE sites.”12 Originally, subcommittees were formed at four DOE facilities including Hanford, Fernald, Idaho National Laboratory (INL), and the Savannah River site. The Oak Ridge HES was established in 2000. The HESs were used as the primary mechanism for public involvement in NCEH activities at DOE facilities (COSMOS 2001a, 2001b).

These subcommittees were used by NCEH, NIOSH, and ATSDR to facilitate public involvement. Several HESs had subgroups that dealt with and provided advice on public communication issues (NCEH/ATSDR 2006). The general public was informed about meetings through announcements in local papers, flyers sent to area libraries, the DOE facility, direct mailings, and announcements in the Federal Register. At the meetings, the subcommittees often made consensus recommendations to the agencies. More details about recommendations and an evaluation of the Hanford and Oak Ridge HESs are discussed in the case studies of these sites in the annexes to this chapter.

To make sure that the HESs were operating effectively, HHS sponsored an independent evaluation of their activities. The evaluation was conducted by the COSMOS Corporation in 2001 and covered the years 1999-2001. The COSMOS study examined four HES programs: Fernald, Hanford, INL, and the Savannah River site. The committee cites this study extensively because it is the one example that the committee has been able to identify within the scope of its review in which a large-scale independent external evaluation has been conducted of any of HHS’s communication activities.

The evaluation criteria and questions contained in the COSMOS report addressed both process and outcome dimensions of the HES’s communication program. COSMOS gathered its information by (1) conducting interviews with representatives from the agencies (NIOSH, NCEH, ATSDR, DOE), HES chairs, and affected community members; (2) distributing surveys to HES members; and (3) reviewing minutes from HES meetings (COSMOS 2001a, 2001b). The COSMOS evaluation included “findings about the operations, effectiveness, and outcomes of the advisory process” in addition to addressing five evaluation questions (COSMOS 2001a):

-

How effective are the subcommittees in providing relevant and timely advice to the agencies on site-specific public health activities and research?

-

How effective are the agencies in providing feedback on the advice received from the subcommittees; considering this advice in decision making; and creating or changing programs, policies, and practices to reflect advice?

-

To what extent are the advisory systems’ efforts to promote public involvement helping to improve perceptions that the public health activities and research are credible and to improve trust between groups?

-

To what extent is the advisory system helping to deliver the appropriate prevention services?

-

Is the FACA-chartered subcommittee process the most appropriate and effective mechanism for obtaining public involvement in health research and public health activities?

Among the findings from the evaluation were the following:

-

Regarding the public benefits of the subcommittees, these included “providing a formal way of advising the government on public concerns; improving communication with the government; and providing access to information.” In addition, the agencies noted that the process encouraged them to learn more about community concerns (COSMOS 2001a).

-

While outreach by the HESs was not identified as a specific subcommittee function by the FACA charter, implementing outreach activities by the subcommittees could achieve several key objectives of the advisory process. These included broad public participation in public health activities and research, representation of diverse viewpoints on the subcommittee, communication of the findings of public health activities and research, and identification and communication to the federal government of the community’s concerns. The report noted that at the time, confusion existed among some agencies about the appropriateness of subcommittee outreach activities. Also, agencies had allocated “relatively few resources to outreach activities” (COSMOS 2001a).

-

NCEH and ATSDR should evaluate the value of subcommittee’s outreach activities and, if indicated: “1) identify outreach as an expected subcommittee function in the next FACA charter, and 2) allocate resources to support subcommittees’ outreach activities” (COSMOS 2001a).

-

In collaboration with the HES, ATSDR and NCEH should continue to evaluate and assess the effectiveness of the HES.

Further information on this evaluation is continued in the discussion of the Hanford site in the annex; however, it is important to note that in 2000, the director of the Hanford Education and Action League evaluated the HES and concluded that “the Hanford Health Effects Subcommittee stands as a sterling example of what can be accomplished when citizens are included early and often to deal with complex issues” (NCEH/ATSDR 2006). When HES subcommittee members were asked about the impact of NCEH and ATSDR at the sites, they noted that “health care providers are more aware than they used to be about potential health effects of chemical and radiation exposure at the DOE sites because of the work of CDC and ATSDR.” Also, many HES subcommittee

members reported that ATSDR played an important role in improving health education at the sites (COSMOS 2001a, 2001b).

Community and Tribal Subcommittee

In 1997, ATSDR established the Community and Tribal Subcommittee. The subcommittee, whose membership includes people living near Superfund sites as well as individuals representing organizations, was charged with the following: “(1) serv[ing] as an advocate for communities; (2) serv[ing] as a sounding board for ATSDR to develop policies and programs related to communities; (3) serv[ing] as a conduit to provide input, opinions, and feedback from communities to the BSC; and (4) facilitat[ing] outreach for the BSC to communities” (ATSDR/ NCEH 2006). The subcommittee also developed The Community/Tribal Advisory Process: A Citizens’ Guide (ATDSR/NCEH 2006).

ATSDR has reported that as a result of recommendations from the Community and Tribal Subcommittee:

-

“ATSDR worked with EPA to include health-based technical assistant grants in the Superfund Technical Assistance Grant program.

-

ATSDR established a formal Office of Tribal Affairs that coordinates ATSDR activities with tribes impacted by Los Alamos and Hanford.

-

ATSDR produced a video to train agency staff on how to work more sensitively with diverse communities and culture” (ATSDR/NCEH 2006).

Committee Evaluations of Site-Specific Communication Efforts

In addition to reviewing the overall agency dissemination and communication activities, the committee reviewed these activities in detail at three DOE sites: Hanford, Oak Ridge, and Los Alamos. These reviews are described in Annexes 5A, 5B, and 5C, respectively, to this chapter. The committee’s conclusions from these reviews are summarized in the following sections.

Hanford Community

NIOSH and NCEH Many of the dissemination and some communication efforts at Hanford for these two agencies have been evaluated earlier in this chapter under the non-site-specific activities of these agencies. Related to additional communication activities, discussions held by the committee with 13 knowledgeable non-DOE and non-HHS individuals involved with Hanford from 1990 to 2005 revealed some consistent themes regarding both NIOSH and NCEH. First, there was awareness—in some cases, quite detailed—of the information dissemination activities of these two agencies. While value was placed on the techniques

of presentations at many types of public events, press releases, and the printed materials previously described, particular emphasis was placed on NIOSH’s efforts to inform workers and their representatives—and site managers—of both the progress and the results of various NIOSH projects. The Hanford Tanks Vapor Study was specifically mentioned several times as a good, recent example of NIOSH endeavors and also of a study that had a direct effect on policies and practices at Hanford.

There was also general agreement on a less positive feature. With only a few exceptions for both agencies, decisions about what to study, and how to study it, were made seemingly without any advance consultation with any affected workers or the general public or with technical experts affiliated with them. Similarly, while the one-way dissemination of progress and results was often quite satisfactory, there generally was no effective two-way communication back to either agency regarding, for example, midcourse additions or suggestions for the study. This was forcefully expressed by technical experts affiliated with various tribes, who perceived that their suggestions regarding potential exposure pathways were ignored (also, in this case, in their interactions with ATSDR).

ATSDR Based on reported materials from ATSDR, the Hanford Community Health Project (HCHP) appears to be a successful program. Its communication materials are understandable and useful to both the lay and the physician community, and its practice of partnering with various professional societies is commendable. Its web site has useful and understandable information and is easy to use. It is laudable that the agency brought in an outside public relations firm to evaluate its communication efforts and then made adjustments to help bring its important health education information to greater numbers of people in the region.

To its credit, ATSDR appears to have attempted to work with community groups and site-specific subcommittees to alter some of its studies or include within its action plans aspects of research or other actions favored by the community. That the agency was so invested in the medical monitoring issue and then that program was not funded indicated to citizens that a program that had been promised and planned over time was never a sure thing. The loss of the Hanford Health Information Network (HHIN) was a blow to many in the Hanford community who felt that this central information network was a considerable asset for informing individuals of happenings related to cleanup and remediation at the site as well as public health issues and may have detracted from the community’s trust in the agency. Whether the HCHP completely fulfilled the role originally established by the HHIN cannot easily be determined, although it did take on some of the group’s activities.

Advisory Groups According to the COSMOS evaluation, the Hanford HES was an active group that sought interaction and provided advice to NCEH and ATSDR. It appeared to be fully involved in many activities, providing advice that some-

times was used. The DOE site advisory board seemed much more removed from most HHS communication activities, and this was a missed opportunity for the HHS agencies to communicate with site opinion leaders and, through them, the various groups they represent.

Mass Media The newspapers examined provided frequent coverage of activities at Hanford, including relating scientific studies in lay language for workers and citizens. They also covered a number of important issues such as medical monitoring and cleanup concerns. They were actively engaged in relating Hanford information to readers in both Washington and Oregon.

To conclude, Hanford was rich in dissemination and communication opportunities for the HHS agencies, particularly going beyond conventional programs and developing ones that serviced an anxious worker and citizen population.

NIOSH and NCEH appear to have performed only their required communication tasks and not taken advantage of the potential for working with stakeholders in a more meaningful way. The exception to this is the TSP’s activities for HEDR, which were truly comprehensive and impressive as early communication efforts. ATSDR, given its mandate, had more flexibility to work directly with citizens, adjusting some programming and research to meet concerns and needs, in particular by developing the HCHP. Its programs appeared to be effective and, according to the agency, reached large numbers of individuals. However, without independent outside evaluation, the committee cannot estimate the impact of any of these programs on Hanford workers, their families, and other citizens in the region.

Oak Ridge Community

In the absence of any independent professional evaluation, assessment of the effectiveness and impact of all communications efforts with communities at the Oak Ridge Reservation and surrounding area is subjective and anecdotal. Comparing the communication and outreach situation in Oak Ridge in 2004 versus 1990 at the beginning of this program, it is safe to say that progress was made.

ATSDR should be given high grades for its very active and engaged connection with the Oak Ridge communities. It offered opportunities for the workers and the community in general to air their health concerns as well as to provide informative presentations to professionals in the medical community and the general public. The briefs that it published attempted to inform the populace on various issues that had been brought to their attention through community meetings. It is difficult to judge the value of this information to members of the community since there was no independent assessment of the communication effort. The committee feels that the communication efforts stopped short of achieving an open and trusting dialogue at this site, as evidenced by published

letters to the editor in the Oak Ridger, a local newspaper, which indicated a divided option regarding the closing of the ATSDR office in Oak Ridge last year.