2

Changing the Adversarial Culture of the Construction Industry

Summary of a Presentation by Thomas J. Stipanowich, President and CEO

International Institute for Conflict Prevention and Resolution (CPR Institute)

The construction industry continues to function as a laboratory and proving ground for approaches aimed at avoiding and resolving conflict. Arbitration, once touted as the “end-all, be-all” replacement for litigation, has not fulfilled its promise. Ultimately, like litigation, arbitration is a last resort. Mediation has proven itself to be a much more appropriate and flexible tool for resolution of a wide range of issues and relational dysfunction, and processes such as the dispute resolution board offer the possibility of “real time” dispute resolution. The ongoing quest for more effective methods of managing conflict continues as we focus increasingly on the root causes of conflict and early intervention.

EVOLUTION OF ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION PRACTICES

Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) continues to gain ground in the business sector, although the picture is very mixed. The 1997 Cornell University/Prevention and Early Resolution of Conflict (PERC) survey of Fortune 1000 Companies was the first major efforts to capture any information about dispute resolution in the business sector. Of the more than 600 survey respondents, the great majority claimed experiences with mediation and arbitration; 87 percent used mediation. However, four out of five respondents said they mediated “only occasionally.”

A follow-up study of a small number of companies suggests that major businesses tend to fall into one of three categories when it comes to conflict resolution. A small percentage of businesses tend to rely rather heavily on litigation and reflect a particular propensity to go to court. A minority purport to manage conflict proactively and rely on ADR. The great majority, however, pursue ad-hoc methods of dispute resolution. Many of these companies used dispute resolution tools, but they were doing so with a “litigation mentality.”

VARIABLES ENCOURAGING CORPORATE USE OF ADR

A number of external and internal variables encourage corporate use of ADR techniques. External factors include perceived liability risks, the cost of judicial resolution, the regulatory environment, and judicial or administrative encouragement of ADR. Internal factors include supportive leadership, ADR champions, and a corporate culture that espouses experimentation and innovation.

Numerous perceived obstacles to constructive conflict management in companies exist. These include: contentious or competitive corporate cultures; the personal or emotional investment of business managers in disputes; business managers who abdicate their problem-solving responsibilities and pass the problems to their lawyers; lack of supportive leadership; a corporate culture that discourages new solutions; the misalignment of incentives within companies and law firms, including traditional hourly billing arrangements; and a professional legal culture that seeks “perfect” information before deciding how to dispose of a case.

CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY CHALLENGES

Use of ADR is critical in the construction industry, which is a “crucible of conflict.” Construction, which produces long-term, unique, and complex projects, is a high stakes endeavor. Stakeholders have limited control over the job environment and bring varying, and sometimes conflicting, perspectives to each project. Aggressive scheduling further opens the door to problems and disputes.

Traditional principles for managing conflict are to resolve conflicts quickly and informally, get technical input if necessary, keep the job moving, and avoid the court system. Prior to the 1990s, disputing parties would deal face-to-face to resolve a conflict and seek opinions from experts such as design professionals. Binding arbitration was the usual next step.

BINDING ARBITRATION: POSSIBILITIES AND PROBLEMS

According to the Cornell/PERC survey, companies used binding arbitration with the expectation that it would save time, would be more satisfactory than litigation, would involve expert decision makers, and would allow for privacy. It was also perceived that binding arbitration placed limits on liability. However, several concerns act as barriers to the use of arbitration: (1) limited appeal, (2) a perceived propensity of arbitrators to “split the difference,” and (3) costs and inefficiencies. Also, disputing parties tend to lack confidence in arbitration because of a lack of qualified arbitrators and uneven administration of the arbitration process. In a 2002 survey of experienced arbitrators in the United States, 31 out of 42 respondents indicated that “arbitration is becoming too much like court litigation and thereby losing its promise of providing an expedited and efficient means of resolving commercial disputes….” On the other hand, a 2004 Corporate Legal Times Survey found that 59 percent of respondents thought that arbitration was less expensive than litigation and 70 percent thought that arbitration was faster than litigation.

According to the Conflict Prevention and Resolution (CPR) Institute Commission on the Future of Arbitration, “choice is the key benefit of arbitration.” Arbitration affords the disputing parties flexibility and autonomy in making process choices because the business needs and goals in dispute management vary and arbitration can be tailored to specific needs and goals. However, arbitration, like litigation, should be a last, not first, resort. There are other, better options beginning with face-to-face negotiation. Other options include evaluation, dispute review boards, mediation, and mini-trials.

There is also concern about over-regulation of arbitration processes spreading to the construction industry. For example, a recent modification of the California Arbitration Act (aimed primarily at consumer and employment arbitration) establishes stringent requirements for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest by arbitrators in commercial cases and permits parties to disqualify the arbitrators based on such disclosures within 15 days after receiving the statement of disclosures. A recent court decision states that statutory requirements trump provisions of commercial arbitration rules, which purports to give the California Arbitration Act, or other administering institutions, authority to decide issues relating to arbitrator challenges. Such determinations are making arbitration more problematic for business people in California.

MEDIATION: NON-BINDING SETTLEMENT-ORIENTED APPROACHES

General dissatisfaction with arbitration has spurred a movement to address the root causes of conflict and promote culture change in organizations. The use of mediation as an ADR approach has increased by 10 to 50 percent over the last 3 years, whereas the use of arbitration is static or decreasing.

Mediation is now the most widely used third-party intervention strategy for business conflict resolution because it offers:

-

Control,

-

Customization,

-

Confidentiality,

-

Communications,

-

Cost savings,

-

Creativity in results,

-

Continuing relationships, and

-

Cultural change.

In the past, companies feared that mediation would be interpreted as a sign of weakness or that it would reveal too much information to the other side. Other fears were that mediation would set a floor on damages, would waste time and money, and could open the floodgates on lawsuits. Finally, there were concerns that if mediation failed once, it would fail again.

Corporate experience with mediation has undermined these myths and fears. According to the 2002 CPR Corporate Survey, most respondents cited settlement rates for mediation in the 80 to 90 percent range. They also reported being highly satisfied with mediation under private auspices, with cost savings averaging $500,000 or more. In contrast, few companies reported more than moderate satisfaction with arbitration and litigation and negligible, if any, savings.

Mediation is most well developed in common law countries including the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Mediation is beginning to receive attention and some use by businesses in many other places, including the European Union, Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, Latin America, the Far East, China, Japan, and India. China, one of the fastest growing economies in the world, has developed a mediation center because it recognizes mediation as an absolute necessity in the modern business world and sees an opportunity to promote international trade and growth; however, it may be some time before mediation in a form recognizable to westerners is a widely used to resolve business disputes.

ELEMENTS OF CORPORATE CONFLICT MANAGEMENT PROGRAMS

In addition to arbitration and mediation, ADR encompasses other innovative strategies, outlined in the 2002 CPR survey of corporate conflict management programs:

-

ADR point person and ADR counsel in the organization,

-

Participation in the CPR Institute’s coalition,

-

Negotiation and mediation advocacy training for inside counsel,

-

Incentives such as annual performance reviews to encourage attorneys to seek ADR whenever possible,

-

Incorporation of ADR in the company’s Total Quality Management or Six Sigma Program,

-

Early conflict assessment procedures and standardized analysis to guide fact/case investigations,

-

Formal decision analysis tools (decision tree),

-

Use of ADR Suitability Screen: guidelines in choosing mediation, early evaluation, arbitration, and so forth,

-

Pre-dispute contractual provisions for ADR, including carefully drafted provisions for stepped conflict management,

-

ADR expectations stated in agreements with outside counsel,

-

Alternative billing arrangements,

-

Written settlement guidelines for counsel,

-

Early settlement or mediation as presumptive processes, and

-

Full-scale discovery only with justification.

The CPR Pledge is yet another innovative way to curb litigation. This practice, developed by the CPR Institute, encourages participants to resolve disputes simply and efficiently. More than 800 companies and thousands of subsidiaries, as well as law firms, are parties to some version of this pledge to resolve conflicts out of court when possible.

CHANGING THE CULTURE OF RELATIONAL CONFLICT AVOIDANCE/MANAGEMENT

Businesses have several other options for avoiding and managing conflict on the job. They can allocate risk sensibly and fairly and provide appropriate incentives. They can also tailor a conflict management program to each job.

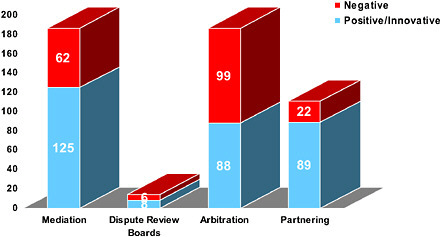

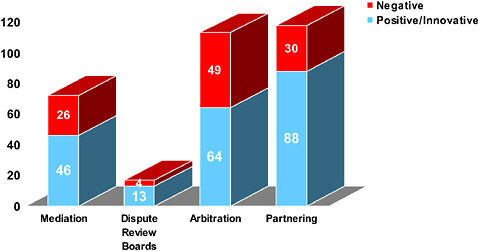

Partnering and team building are particularly effective for developing successful working relationships. According to an ABA/AGC/DPIC survey from the mid-1990s, contractors and architect-engineering (AE) professionals report more positive experiences with partnering than with mediation, dispute review boards or arbitration (see Figures 2.1 and 2.2).

Successful partnering addresses myriad project concerns:

-

Job roles and responsibilities,

-

Scheduling and document control,

-

Design issues,

-

Procurement,

-

Construction process,

-

Risk allocation and incentives,

-

Changes and modifications occurring after project completion, and

-

Groundwork for managing conflict through a tailored conflict resolution system.

TEN-STEP MODEL FOR BUSINESSES AND COUNSEL

The CPR 10-step model for avoiding conflicts and managing them is one of the most important tools any organization can use to manage conflict and achieve project goals. It is as follows:

-

Develop corporate policy strategies on avoiding conflict and conflict management, with leadership from the top.

-

Use a collaborative team approach.

-

Demand working knowledge of the full range of conflict resolution tools.

-

Pursue continued collaboration between business managers and house counsel so as not to lose control of projects. House counsel plays a stronger team leadership role with outside counsel.

-

Implement early conflict assessment.

-

Make ADR approaches an integral part of broader company policy.

-

Ensure considered use of mediation, evaluation, arbitration, and so forth.

-

Insist that outside law firms align their practices with corporate goals.

-

Use benchmarking and cost measurements to avoid repeating mistakes and ensure that ADR strategies are working.

-

Emphasize lessons learned and provide feedback to the legal team and to clients.

Benchmarking and feedback are important elements of the 10-point model because they enable organizations to measure results, improve processes and performance, and build an atmosphere of trust with project partners and clients.

FUTURE OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION AND ADR

Dispute resolution is about getting to the root causes of conflict. We can achieve this goal through multidisciplinary approaches and changes in the prevalent culture.

We have not yet achieved our goals because we lack leadership from business and from the legal profession in taking on responsibility for dispute management. There is also fear of change or of taking risks without support from decision makers, and often a lack of time and imagination to break down boundaries between business and law.

The construction industry can be a model for any sector with complex multiparty projects and relationships. A revolution began 20 years ago, but that revolution is still in progress. Businesses must take the lead, but we all have a part to play.

ABOUT THE INSTITUTE

The International Institute for Conflict Prevention and Resolution (CPR), created 25 years ago, is a nonprofit alliance of global corporations, law firms, scholars, and public institutions dedicated to the principles of conflict prevention and “appropriate dispute resolution.” CPR helps companies manage conflict and avoid litigation, arbitration, and related risks and high costs. It also seeks to empower the business sector, including the construction industry, to control dispute resolution rather than rely solely on attorneys. CPR, which is gradually expanding its work into Europe, Asia and other parts of the globe, provides three primary services: conferences, workshops and other convening activities; dissemination of information in print, electronic and other forms; and dispute resolution through panels of distinguished neutrals and facilitated negotiation.

RESOURCES

CPR Institute for Dispute Resolution. Available online at www.cpradr.org.

Folberg, J., D. Golann, L. Kloppenberg, and T. Stipanowich, Resolving Disputes: Theory, Practice and Law, Aspen Publishers, New York, N.Y., 2005.

Institute on Conflict Resolution. Available online at www.ilr.cornell.edu/icr.

LexisNexis Martindale-Hubbell 15th Annual Survey of General Counsel. Corporate Legal Times, Volume 14, No. 152, July 2004. Available online at www.martindale.com/pdf/c2c/clt_2004_survey.pdf.

Lipsky, D.B., and R.L. Seeber, The Appropriate Resolution of Corporate Disputes: A Report on the Growing Use of ADR by U.S. Corporations, Cornell University Institute on Conflict Resolution, Ithaca, N.Y., 1998.

Scanlon, K.M., CPR Drafter’s Deskbook for Dispute Resolution Clauses, CPR Institute (International Institute for Conflict Prevention and Resolution), New York, N.Y., 2002.

Stipanowich, T.J., and P. Kaskell, eds. Commercial Arbitration at Its Best: Successful Strategies for Business Users, CPR Institute (International Institute for Conflict Prevention and Resolution), New York, N.Y., 2000.