4

SSA’s Disability Programs

The subject of disability insurance was discussed and debated extensively from the very beginnings of Social Security, although in the end, the original 1935 Social Security Act did not contain a provision for the payment of disability benefits. Many people thought that the program should include wage replacement for individuals who became unable to work before age 65 due to disability. However, there was much debate about the potential costs of such a program and about the complexity of administering it. “There was concern about the dynamic nature of the disability program, and the administrative difficulty in making disability determinations, i.e., the subjectivity of determining whether a person was truly disabled or out of work for other reasons such as age, obsolete skills or experience, etc.” (SSA, 1996:1).

Between 1935 and passage of the Disability Freeze in 1954 (followed shortly by the Disability Insurance program in 1956), the Social Security Board (which became the Social Security Administration [SSA] in 1946) and Congress worked extensively on the design of a disability benefit program. However, “the administrative problems of separating those truly unable to work from those merely out of work colored the debate over disability insurance and delayed its passage” (Berkowitz, 1987:41).

As the political debate about whether to establish a disability program continued, officials within SSA were working on the difficult problem of how to implement such a program if it eventually passed. They recognized the complexity of making disability determinations, and they knew that they had a great deal of preparatory work to do. As later recalled by one of the key figures in the development of the disability program:

… as we approached the 1950s, it looked like disability insurance was coming—and we had to study how it would be administered. I found that there was little or no appreciation and no detailed work being done on how Social Security would go about administering various conceivable provisions (Hess, 1993:6, 7).

Early on, officials at the Social Security Board decided that the definition of disability for any disability benefit program had to be a strict one to be politically acceptable and financially feasible. They also recognized that the concept of disability was highly elastic and that determining disability was likely to be quite imprecise. They thought that too strict a definition might result in pressure to “swing in the opposite direction” (Berkowitz, 1987:44). The definition they chose, which became the model for the definition that was eventually adopted in the legislation establishing the disability freeze and disability insurance benefit programs many years later, was borrowed from the War Risk Insurance Act (administered by the Veterans Administration), which defined disability as:

Any impairment of mind or body which continuously renders it impossible for the disabled person to follow any substantial gainful occupations, and which is founded on conditions which render it reasonably certain that the total disability will continue throughout the life of the disabled person (cited in Berkowitz, 1987:44).

The definition of disability eventually adopted in the Social Security Amendments of 1954 was:

Inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or to be of long-continued and indefinite duration (cited in SSA, 1996:2).

The Social Security definition of disability has evolved over the last 50 years, especially in the 1960s. In 1965, the definition was changed, easing the strictness of the duration requirement. Impairments were no longer required to “be of long-continued and indefinite duration.” Rather, the impairment only had to last or be expected to last for 12 months. In 1967, the law was again amended in response to a series of judicial decisions that placed an increasing burden on the SSA to establish the existence of jobs that denied applicants might reasonably obtain. The change in the definition was intended to emphasize its medical focus by providing that an individual would be found disabled “only if his physical or mental impairment or impairments are of such severity that he is not only unable to do his previous work but cannot, considering his age, education, and work

experience, engage in any other kind of substantial gainful work which exists in the national economy, regardless of whether such work exists in the immediate area in which he lives, or whether a specific job vacancy exists for him, or whether he would be hired if he applied for work.” In order to further emphasize the importance of medical factors, the 1967 law changed the definition to state that a physical or mental impairment is “an impairment that results from anatomical, physiological, or psychological abnormalities which are demonstrable by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques” (Kollmann, 2000; SSA, 1996).

Initially, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) covered insured workers between 50 and 65 and dependent children 18 or over of deceased or retired workers who had become disabled before age 18. It was subsequently expanded to provide benefits to nondisabled dependents of workers. The Social Security Amendments of 1960 eliminated the minimum age requirement of 50, which increased the range of disability benefits to workers between 18 and 65. Supplemental Security Income (SSI), launched in 1974, provided benefits to disabled children through age 17 as well as adults 18-65.

INITIAL DISABILITY CLAIMS PROCESS

In order to apply this definition of disability in 2.6 million disability claims per year, SSA has established a fairly complex disability claim process. Generally, an individual claiming entitlement to disability benefits (referred to as the “claimant”) files the initial application with one of SSA’s 1,138 field offices or 35 teleservice centers distributed across the country, either in person, by telephone, by mail, or over the Internet.1 Field office personnel gather information about:

-

the nature of the claimant’s disability and how it limits the ability to work

-

the claimant’s medical treatment sources, medications, and tests

-

the claimant’s work history, education, and training

-

any other matters that relate to the alleged disability

The field office also gathers information about nondisability issues. Depending on the type of claim and the specific case circumstances, these might include the claimant’s age, employment history, marital status, or financial resources. The field office then determines if the nondisability eligibility requirements are met (for example, whether the claimant is insured

for SSDI benefits). If so, the field office sends the case to a state Disability Determination Service (DDS) agency to determine whether the claimant is “disabled” according to SSA law.

With the exception of a single federal unit that is located in SSA’s central office, all DDSs are state agencies fully funded by SSA. The 54 state and territorial DDSs are responsible for making the initial decision about whether an individual is disabled. Upon receiving a new claim from an SSA field office, a DDS obtains medical records from the claimant’s own medical sources. If necessary, the DDS may also obtain additional medical evidence on a consultative basis from independent medical sources. Based on all the medical and other information, the DDS makes the initial disability decision and then returns the case to the field office. If the DDS finds the claimant to be disabled, the field office then completes the paperwork and initiates the benefit payments. If the DDS finds the claimant not disabled, the field office retains the file in case the claimant requests an appeal.

THE ADMINISTRATIVE REVIEW (APPEAL) PROCESS

A claimant who is dissatisfied with the initial disability determination may appeal the determination, making use of SSA’s administrative review process, often referred to as the appeal process.2 SSA’s appeal process consists of four levels, which usually must be followed in order and within specific time limits. Generally, an individual who wishes to appeal the decision made at any level must make the appeal within 60 days of the decision or lose the right to further review.

The administrative review process is informal and nonadversarial. Claimants may present any information they believe to be relevant, and may be represented by someone, including (but not limited to) an attorney. The four levels of the administrative review process are:3

-

Initial Determination—For disability decisions, the initial determination is generally made in a state DDS by a two-person adjudicative team

|

2 |

SSA’s administrative review process is described in the Code of Federal Regulations in title 20, part 404, subpart J, and title 20, part 416, subpart N (20 CFR §§ 404.900-999 and 416.1400-1499). See also, The Appeals Process. SSA Publication No. 05-10041, January 2006. Available: www.ssa.gov/pubs/10041.html (accessed October 5, 2006). |

|

3 |

SSA has been testing modifications to its disability determination procedures under the authority of 20 CFR §§ 404.906, 404.966, 416.1406, and 416.1066, and some of these tests involve changes to the appeal process. For example, certain states are testing a prototype process that eliminates the second step of the appeal process, the reconsideration step. In addition, SSA recently published new rules (71 FR 16424, March 31, 2006) describing a gradual roll out of several substantive changes to the current administrative review process. These changes, which are discussed later in this chapter, were implemented in the Boston region in August 2006. |

-

consisting of a medical or psychological consultant and a lay disability examiner.

-

Reconsideration—Reconsiderations of initial disability determinations are also processed by the state DDS, but by a different adjudicative team than the one that made the initial decision.

-

Hearing—Hearings on disability cases are conducted by administrative law judges (ALJs), who are appointed by the associate commissioner for hearings and appeals. There are about 1,100 ALJs located in 144 hearings offices distributed around the country. The claimant may personally appear at the hearing and can bring witnesses. He or she may also submit new evidence and review the evidence used in the decision. The ALJ may also ask other witnesses to appear. For example, the ALJ may ask for testimony from a medical or vocational expert, and does so in about 12 and 46 percent of the hearings, respectively (SSA, 2005b). The ALJ makes the hearing decision based on the evidence and testimony presented.

-

Appeals Council Review—A claimant may request review of an ALJ disability decision by SSA’s Appeals Council. Administrative appeals judges (AAJs) on the appeals council will grant such a request for review only in specific circumstances. Otherwise, the ALJ’s hearing decision becomes SSA’s final administrative decision in the case.

After completing all steps of the administrative review process, if a claimant is still dissatisfied with SSA’s final decision, he or she may ask for judicial review by filing a civil lawsuit in federal district court.

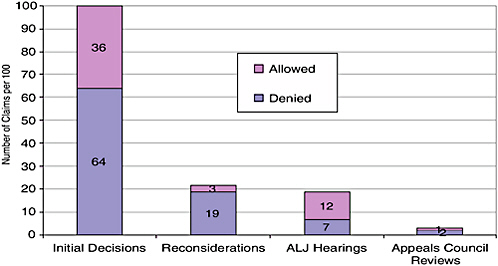

For every 100 disability claims decided in FY 2005, DDSs allowed about 36 at the initial decision step. Of the remaining 64, about 22 appealed for reconsideration. DDSs approved about 3 of the 22 reconsiderations and denied about 19, almost all of whom filed a second appeal requesting a hearing before an ALJ. ALJs approved about 12 and denied about 7, 3 of whom filed a third appeal requesting review by the appeals council. The appeals council approved 1 and denied 2 (see Figure 4-1).

THE DISABILITY DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

The process used for making a disability decision is the same, regardless of the level at which the decision is made in the administrative review process (initial, reconsideration, hearing, or appeals council review), and regardless of the specific personnel or components involved (a disability examiner/medical consultant team in a DDS, ALJ in a hearing office, or AAJ at the appeals council).

Under the Social Security Act, an individual is considered to be “disabled” for Social Security purposes if he or she is unable “to engage in

FIGURE 4-1 Percentages of allowances and denials at each stage of the claims process.

NOTE: Data based on decisions made during FY 2005, not on longitudinal tracking of a cohort of claims made in FY 2005.

SOURCE: Based on SSA data accessed April 20, 2007, at: www.ssa.gov/disability/disability_process_welcome_2005.htm.

any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.”4 Further, “[a]n individual shall be determined to be under a disability only if his physical or mental impairment or impairments are of such severity that he is not only unable to do his previous work but cannot, considering his age, education, and work experience, engage in any other kind of substantial gainful work which exists in the national economy …”

This definition of disability is complex, and it has medical, functional, and vocational components. A complete and comprehensive assessment of all aspects of the definition would require a detailed clinical evaluation of the underlying medical cause(s) for the impairment; analysis of the expected duration of the impairment (prognosis); a comprehensive assessment of the work-related functional limitations attributable to the impairment as well as the individual’s remaining functional capacity; a detailed vocational analysis of the individual’s work history and acquired work skills, educational

background, and age; and a thorough analysis of the individual’s current vocational prospects. However, SSA does not have the resources to perform such an extensive assessment for each of the approximately 2.6 million disability applicants who will come through its doors each year.

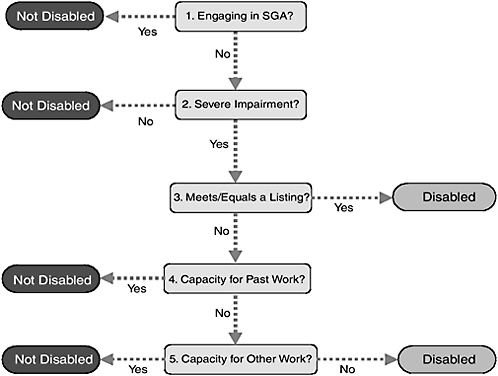

To apply the statutory definition in a way that allows it to manage its caseload, SSA uses a five-step sequential evaluation process when deciding whether an individual is disabled. The five-step process is used by the DDS at the initial and reconsideration decision levels and in the quick disability determination process being piloted in Region 1. Only the last step of the process requires a complete, comprehensive assessment of all aspects of the definition of disability. Each of the four steps that precede it is, to some degree, intended to enable the DDS to reach a faster decision by looking only at selected aspects of the case. The first, second, and fourth steps identify cases that will be denied without performing a complete assessment of all aspects of the case. The third step identifies cases that will be allowed without a complete assessment (Figure 4-2).

FIGURE 4-2 SSA’s five-step sequential disability evaluation process.

SOURCE: 20 CFR §§ 404.1520 and 416.920.

The five-step sequential evaluation process is as follows:

Step 1. Is the individual working and engaging in “substantial gainful activity”?

-

If so, the individual is not disabled. The claim is denied and there is no further evaluation.

-

If not, no decision is made and the evaluation proceeds to step 2.

Step 2. Does the individual have an impairment or combination of impairments that significantly limits his or her physical or mental ability to do basic work activities?

-

If not, the individual is not disabled. The claim is denied and there is no further evaluation.

-

If so, no decision is made and the evaluation proceeds to step 3.

Step 3. Does the individual have an impairment(s) that meets or equals the severity of an impairment listed in the Listings (Appendix 1 of subpart P of part 404 of SSA’s regulations)?

-

If so, the individual is disabled. The claim is allowed and there is no further evaluation. If not, no decision is made and the evaluation proceeds to step 4.

Step 4. Considering the individual’s residual functional capacity (RFC) and the physical and mental demands of the work he or she did in the past, does the individual’s impairment(s) prevent him or her from doing past relevant work?

-

If not, the individual is not disabled. The claim is denied and there is no further evaluation.

-

If so, no decision is made and the evaluation proceeds to step 5.

Step 5. Considering the individual’s RFC, age, education, and past work experience, is he or she able to do any other work?

-

If so, the individual is not disabled. The claim is denied.

-

If not, the individual is disabled. The claim is allowed.

The third step of the five-step sequential evaluation relies on the Listing of Impairments (the Listings) to identify cases that will be allowed. The Listings describe impairments that SSA considers severe enough to prevent an individual from doing “any gainful activity.”5 The “any gainful activity” standard is a stricter standard (i.e., a higher degree of impairment severity)

than the “any substantial gainful activity” standard in the definition of disability.

DISABILITY DECISIONS OUTCOMES AND THE SEQUENTIAL EVALUATION PROCESS

In 2003 (the most recent year for which complete data for both programs are available), SSA made favorable medical decisions on 37 percent of the initial claims filed under either SSDI or SSDI/SSI concurrently and on 38 percent of the SSI-only claims. After the appeals process, in which additional allowances were made, the favorable medical decision rates were 53 and 46 percent for SSDI and SSI, respectively. However, because a substantial percentage of claims were pending, the allowance rates on appeal are probably understated and will rise as the remaining 2003 claims complete all appeals. In recent years, the eventual overall allowance rate has been more than 60 percent for SSDI cases and more than 50 percent for SSI cases (SSA, 2006b:Tables 53, 54; 2005a:Table 53, 54).

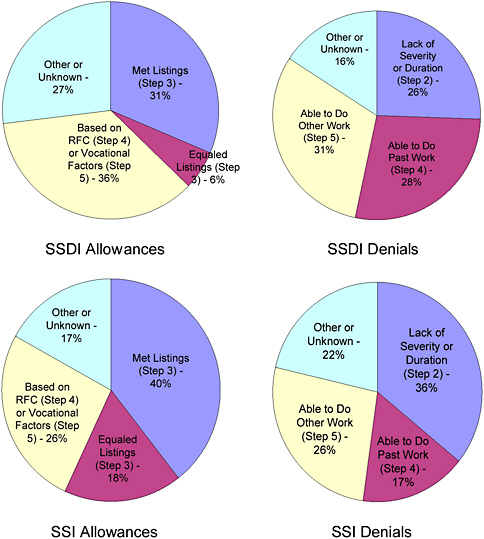

For the same year, SSA allowed benefits for SSDI and SSDI/SSI concurrent cases on the basis of the Listings in 44 percent of allowances and on the basis of medical/vocational factors in 42 percent of allowances. For adult SSI claims, 46 percent of the allowances were based on the Listings and 36 percent on the basis of medical/vocational factors. (The remaining allowances—14 percent of SSDI and 19 percent of adult SSI—were applications for which the disability was previously established or the basis for the determination unknown. The majority of “unknown” cases were allowed at or above the hearing level.)

SSA denied benefits for SSDI cases for insufficient impairment severity or duration in 17 percent of the denials, for capacity to do usual past work in 28 percent of denials, and for capacity to do other type of work in 31 percent of denials. For adult SSI cases, 12 percent of the denials were based on insufficient impairment severity or duration, 22 percent on ability to do past work, and 35 percent on ability to other work. (The remaining denials—24 percent of SSDI and 31 percent of adult SSI—were based on a variety of other causes, such as insufficient evidence, failure to cooperate, and cases at or above the hearing level in which the basis of the denial is unknown; SSA, 2006b:Tables 57, 58; 2005a:57, 58). See Figure 4-3.

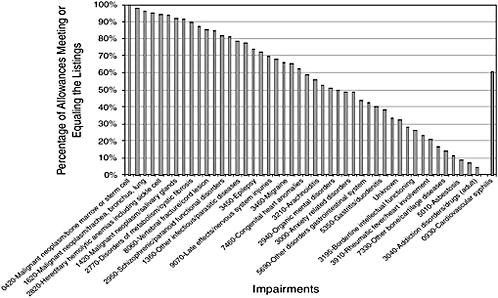

The percentage of allowances based on meeting or equaling the Listings varied widely from condition to condition (Figure 4-4). Conditions in which allowances are based mostly on the Listings (i.e., on the left side of Figure 4-4) include malignancies, such as melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and lung cancer; ALS; Down syndrome; deafness; blindness; chronic renal failure; and spinal cord injury. Conditions in which about half the allowances are based on the Listings include Parkinson’s disease; congenital

FIGURE 4-3 Bases for allowances and denials, by program segment, 2003.

NOTE: Totals may not equal 100 percent because of rounding.

SOURCE: SSA, 2005a:124-126, 2006b:131-132.

heart anomalies; and many of the mental disorders, such as organic mental, somatoform, personality, and anxiety-related disorders. Conditions on the right side of the figure, such as back and other musculoskeletal disorders, osteoarthritis, diabetes mellitus, and chronic ischemic heart disease are not usually allowed at the Listings step (6, 8, 13, and 18 percent of the time, respectively).

FIGURE 4-4 Percentage of allowances made on the basis of meeting or equaling the Listings, by selected impairment codes, 2004.

NOTE: The bar on the right denotes the median allowance rate, 61 percent.

SOURCE: Data provided by SSA.

PROBLEMS WITH THE DISABILITY DECISION PROCESS

Problems with SSA’s current system for determining eligibility for disability benefits include:

-

the length of time it takes to process a claim to completion

-

the variability in decision outcomes among different state DDSs, among different Office of Hearings and Appeals (OHA) offices, and between DDSs and OHA

-

the high rate at which decisions are reversed on appeal

In recent years, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has conducted many reviews of SSA’s disability programs. Because of SSA’s management difficulties—particularly the long disability claim-processing times and inconsistencies in disability decisions across adjudication levels and locations—as well as similar problems experienced by other disability programs, such as those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, GAO added federal disability programs to its list of high-risk government programs in 2003. GAO concluded that concerns about claim-processing time and inconsistency in decisions “raise questions about the fairness, integrity, and

cost of these programs” (GAO, 2006:3-4). In addition, the rate at which unfavorable disability decisions are reversed on appeal is higher than comparable reversal rates for other programs providing benefits to disabled persons. For example, at the Veterans Administration between 22 and 26 percent of initial decisions are reversed upon appeal (Lewin, 2001).

Claim-Processing Time

In FY 2006, it took an average of three months (88 days) for DDSs to process initial disability determinations. Processing time for reconsiderations averaged another three months. On average, it took more than a year (483 days) to process requests for hearings and about seven months (203 days) to process requests for appeals council review (SSA, 2005c:71-72). Although these processing times represent a small recent improvement, the process remains lengthy. In 2002, SSA completed an in-depth examination of disability claim-processing time in FY 2001. It found that, if an applicant went through every step of the SSA appeals process, it averaged 1,153 days for a claim to get through the appeals council level of review and receive a decision (SSA, 2002).6 An update of the study for FY 2004 found that total time in this worst-case situation had been cut by 10 percent to 1,049 days. In actual practice, however, the majority of cases are decided at the initial level and only about 4 percent of initial claims make it all the way to the appeals council (SSA, 2004:17).

In addition to long claim-processing time, there has been an overall upward trend in disability claim filings since 1989 (SSAB, 2006:17) and a corresponding increase in case backlogs. At the DDS initial claim level, case backlogs that totaled less than 300,000 in the late 1980s were nearly 625,000 by 2004. At the ALJ hearing level, the increase has been even more dramatic—from less than 200,000 to more than 700,000 (SSAB, 2006:84-85). By the end of FY 2006, the initial backlog had fallen by 11 percent to 555,000 but the queue for ALJ hearings had grown by 13 percent to 715,000.

Variability in Decision Making

All DDSs throughout the country operate under the same federal procedures for making disability decisions for SSA, yet there is considerable variation among states in decision outcomes. In 2004, the percentage of initial claims allowed by individual state DDSs varied widely, from around 25 percent in low-allowance-rate states such as Tennessee and Mississippi

to more than 50 percent in high-allowance-rate states such as Hawaii, New Jersey, and New Hampshire. There is also wide variation in the bases for allowances. In 2003, initial claims were allowed based on meeting the Listings in less than 35 percent of the initial favorable decisions in New York, Vermont, and Minnesota. But the same basis was used for allowance in more than 55 percent of the initial favorable decisions in Illinois, South Dakota, Indiana, and Oklahoma. In North Dakota, the figure was almost 65 percent. States like Indiana and Washington found impairments equivalent to the Listings in only 2-3 percent of the allowances. In contrast, Vermont found impairments equivalent to the Listings in more than 21 percent of its allowances.

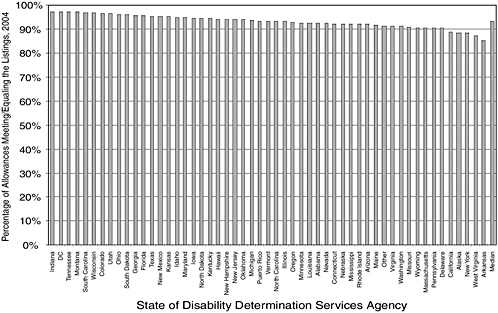

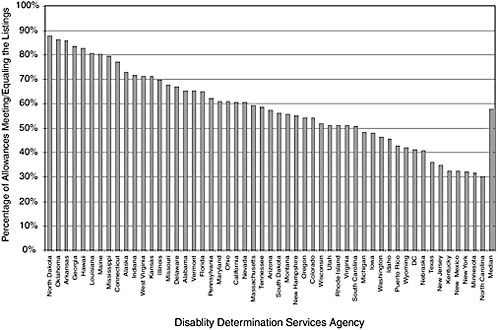

The percentage of allowances based on the Listings varies less across states in some conditions than in others. The percentage of allowances made for malignant neoplastic disease ranges between 85 and 98 percent across DDSs (Figure 4-5). The range is much wider for mental disorders. The percentage of allowances for mental disorders based on the Listings varies between 36 and 86 percent (Figure 4-6).

Variability in decision making is not limited to allowances. North Carolina denied claims because the claimant had no “severe” impairment in

FIGURE 4-5 Percentages of allowances for malignant neoplasms meeting or equaling the Listings, 2004.

SOURCE: Data provided by SSA.

FIGURE 4-6 Percentages of allowances for mental disorders meeting or equaling the Listings, 2004.

SOURCE: Data provided by SSA.

about 5 percent of the initial denials, while Mississippi used the same basis for denial about 32 percent of the time (SSAB, 2006:61-63).

There are also significant state-to-state variations in procedures and administrative arrangements. In 2004, the Vermont DDSs obtained consultative examinations in less than 14 percent of its initial claims, but Tennessee, New York, and Indiana obtained them in more than 60 percent of their initial claims. DDSs “follow State established personnel policies with respect to salaries, benefits and educational requirements; and they do their own hiring, provide most of the training for adjudicators, and establish their own internal quality assurance procedures. Also, reimbursement rates for purchasing medical evidence and diagnostic tests vary from State to State” (SSAB, 2006:7).

ALJs, who decide disability appeals throughout the country, also operate under the same federal rules in making disability decisions. However, data about hearing decision outcomes on a state-by-state basis show considerable variation in outcomes. In 2004, ALJs in Alaska and Louisiana allowed approximately 50 percent of cases, while ALJs in New Hampshire and Connecticut allowed over 80 percent. In addition, there is wide variation in individual ALJ allowance rates (SSAB, 2006:74, 76).

A claimant cannot be awarded disability benefits unless there is a medical basis for his or her impairment. Therefore, SSA relies heavily on medical expertise for claims adjudication. However, not all DDSs or regional appeals offices have access to a full range of medical expertise. For example, according to data supplied to the committee by SSA, in 2004, 29 of 52 DDSs had no medical consultants specializing in cardiology, 28 had no neurologists, and 25 had no orthopedic surgeons or orthopedic specialists.7 There is also variation in expertise available to provide expert testimony at ALJ hearings. In 2005, for instance, ALJs in the Atlanta region had access to expertise within 41 specialties while ALJs in the Denver region had access to 12.

In 2002, the average salary for a DDS examiner was $40,464, compared with $49,684 for examiners working for the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA). The average DDS examiner salary was lower than the average VBA examiner salary in 47 states (GAO, 2004:21). A 2004 GAO study reports that two-thirds of interviewed DDS directors felt that noncompetitive pay was contributing to examiner turnover at their agency (GAO, 2004:20). In 2004, minimum salary levels for initial-level DDS examiners varied significantly among the states, with examiners in low-paying states such as Wyoming, North Dakota, and Tennessee making about half that of examiners in high-paying states such as Connecticut and New York (SSAB, 2006:70).

At the field office level, states do not have formal or systematic quality assurance procedures for evaluation of medical information collected on applications for disability. Occasionally, particularly in complex cases or cases being handled by new field office personnel, claims are reviewed by field office management (Lewin, 2001:25). At the DDS level, states are also not required to have internal quality assurance departments or formal quality assurance procedures in place. At minimum, most DDSs perform an end-of-line review of cases, often to measure disability examiner performance. Beyond that, however, there is wide variability in the quality assurance practices among states, and such activities often change in response to specific quality or workload issues (Lewin, 2001:25).

As summarized by the Social Security Advisory Board (SSAB, 2006:7-8):

Over the years policy makers and administrators have identified many factors, in addition to the inherent subjectivity of the statutory definition of disability, that may affect the consistency of disability decision making. These include:

-

economic differences among the States;

-

demographic differences among the States;

-

differences in health status and access to care;

-

State public policy actions (e.g., eliminating general assistance programs; requiring individuals to file for SSA’s disability programs as a condition of eligibility for State benefits);

-

differences in assessing the accuracy of State decision making among SSA’s regional Offices of Quality Assurance;

-

differences in quality assurance procedures applied to ALJs and State agencies;

-

hearing office differences in administrative practices (e.g., variation in use of and training of vocational and medical experts at ALJ hearings);

-

differences in the training given to ALJs and State adjudicators;

-

differences in State agency training practices;

-

the fact that most claimants are never seen by an adjudicator until they have an ALJ hearing;

-

involvement of attorneys and other claimant representatives at the ALJ hearing;

-

changes in the adjudicative climate (the “message” sent by SSA, the Congress, or others to those who adjudicate claims);

-

rules that allow claimants to introduce new evidence and allegations at each stage of the appeals process;

-

lack of clear and unified policy guidance from SSA;

-

insufficient funding and staffing for the State agencies and for hearing offices; and

-

SSA pressures on State agencies and on ALJs to meet productivity goals.

DISABILITY SERVICE IMPROVEMENT PLAN

In March 2006, SSA issued a final rule implementing a Disability Service Improvement plan. The plan, which SSA began to roll out in August 2006, is intended to “improve the accuracy, consistency, and fairness of [SSA’s] disability determination process and to make the right decision as early in the process as possible” (71 FR 16423-16462). Major features of the plan include:

-

creating quick disability determination (QDD) units within DDSs to identify individuals who are clearly disabled and to make a favorable determination within 20 days

-

establishing a Medical and Vocational Expert System (MVES) to enhance the quality and availability of medical and vocational expertise available to adjudicators

-

creating a new federal reviewing official (FRO) position to review DDS initial determinations at the claimant’s request

-

creating a new decision review board (DRB) to identify and correct errors in decisions and to identify issues that may impede consistent adjudication at all levels of the process

The plan preserves the claimant’s right to request and be provided a de novo hearing conducted by an ALJ, but it closes the case record after the ALJ issues a decision. In addition, the plan eliminates the current appeals council review step.

Quick Disability Determination (QDD) Units

Under the plan, SSA will use a predictive model to screen incoming claims for cases that have a greater likelihood of allowance. Cases received in the state DDSs that are identified by the predictive model will be sent to the QDD unit within the DDS. The files will then be reviewed by a team consisting of a disability examiner and a medical expert. Although both members of the team will decide the case, the medical expert will verify that medical evidence is sufficient to establish that the claimant meets the standards to be established by SSA. If the evidence is insufficient to make a QDD decision, the case will be returned to the DDS.

Medical and Vocational Expert System (MVES)

The plan also calls for establishing a national network of medical, psychological, and vocational experts who meet qualification standards to be set by SSA. A medical and vocational expert unit (MVEU) will help adjudicators at all levels both find and arrange for expert assistance when needed. The MVEU will maintain a registry of medical, psychological, and vocational experts who meet SSA qualifications. Because SSA is currently transitioning to electronic medical records, adjudicators will be able to use experts from across the country, not just experts available within their region.

Federal Reviewing Officials (FROs)

Instead of the current reconsideration process (in which adjudicative teams within the DDSs reconsider the claims of applicants unsatisfied with their initial determinations), the plan calls for establishing a new FRO position to handle the first level of administrative review. FROs will be attorneys who review initial determinations at the request of claimants. Claimants will be able to submit new evidence at this stage, and the FROs will be able to request more evidence from a state DDS (including clarification of the initial determination), consult with medical experts, and request consultative examinations. FROs will affirm, reverse, or modify DDS decisions, but will

not be able to remand cases to DDSs. After a case is developed, an FRO will affirm, deny, or modify the initial determination and notify both the applicant and, for quality assurance purposes, the state DDS of the decision. If an FRO disagrees with the DDS decision, or if new evidence is submitted, he or she will consult with an expert through the MVES.

Decision Review Board (DRB)

The appeals council and its review process will be abolished, and the DRB will be established, composed of experienced ALJs and AAJs appointed by the SSA commissioner. Claimants denied after an ALJ hearing will not be able to initiate appeals to the DRB. Rather, the DRB will select cases for review using a new sampling procedure to identify error-prone or complex ALJ decisions—both allowances and denials.

Claimants will receive notifications that their claims will be reviewed by the DRB along with the ALJ’s decision letters. Claimants will be able to submit written statements to the board within 10 days explaining why they agree or disagree with the ALJ’s decision. The DRB may affirm, modify, or reject an ALJ’s decision, or it may remand a claim back to an ALJ for further review. To improve consistency in disability decision making, a copy of any DRB decision that is in disagreement with the ALJ hearing decision will be sent to the ALJ.

The DRB will have 90 days from the date the claimant was notified that his or case would be reviewed by the DRB to make a decision (this compares with the average time the appeals council takes to complete a case—242 days in FY 2004). If the DRB takes longer, the ALJ’s decision will become the final decision, unless there is the possibility of a decision favorable to the claimant. Applicants whose claims are denied by the DRB will be able to seek judicial review. When a claimant disagrees with an ALJ’s decision and the case is not selected to go to the DRB, the next level of appeal will be to federal district court.

The DRB will also serve several other functions, including review of claims rejected for hearings, handling cases remanded back to SSA from a federal court for further administrative review, and study of claims post-effectuation for understanding and improvement of the disability decision process.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, E.D. 1987. Disabled policy: America’s programs for the handicapped. New York: Cambridge University Press.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2004. Strategic workforce planning needed to address human capital challenges facing the Disability Determination Services. Washington, DC: GAO. Available: www.gao.gov/new.items/d04121.pdf (accessed April 12, 2006).

GAO. 2006. Statement of Robert E. Robertson, Director, Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues. Social Security Administration: Agency is positioning itself to implement its new disability determination process, but key facets are still in development. Washington, DC: GAO. Available: www.gao.gov/new.items/d06779t.pdf (accessed September 28, 2006).

Hess, A. Comments at the January 21, 1993 Disability Forum, the Disability Program: Its origins—our heritage. Its future—our challenge. Available: www.ssa.gov/history/ dibforum93.html (accessed November 3, 2005).

Kollmann, G. 2000. Social Security: Summary of major changes in the cash benefits program. CRS report RL30565. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. May 18, 2000. Available: www.ssa.gov/history/reports/crsleghist2.html (accessed October 6, 2006).

Lewin (The Lewin Group, Pugh Ettinger McCarthy Associations, and Cornell University). 2001. Evaluation of SSA’s disablity quality assurance (QA) processes and development of QA options that will support the long-term management of the disability program. Final Report Prepared for the Social Security Administration. March 31, 2001. Available: www.lewin.com/NR/rdonlyres/ekhzi4f6bl2iwvway5ibsoerh7acjf6lpnwh3etwt6jd246bw5cdaymmastvdiojiljc7jt3cozp3nosoj56dr2k2zf/1325.pdf (accessed April 6, 2006).

SSA (Social Security Administration). 1996. A history of the Social Security disability programs. SSA staff paper produced in 1986. Available: www.ssa.gov/history/1986dibhistory.html (accessed November 3, 2005).

SSA. 2002. Flow of cases through the disability process. Available: www.ssa.gov/disability/disability_process_welcome.htm (accessed September 28, 2006).

SSA. 2004. SSA’s FY 2004 performance and accountability report. Available: www.ssa.gov/finance/2004/Full_FY04_PAR.pdf (accessed April 28, 2006).

SSA. 2005a. SSI annual statistical report, 2004. Released September 2005. Available: www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_asr/2004/index.html (accessed May 22, 2006).

SSA. 2005b. Findings of the disability hearings quality review process. SSA Pub. No. 30-013. Baltimore, MD: Office of Quality Assurance and Performance Assessment, SSA.

SSA. 2005c. SSA’s performance and accountability report for fiscal year 2005. Available: www.ssa.gov/finance/2005/FY_05_PAR.pdf (accessed September 29, 2006).

SSA. 2006a. SSA’s performance and accountability report for fiscal year 2006. Available: www.ssa.gov/finance/2006/FY06_PAR.pdf (accessed December 4, 2006).

SSA. 2006b. Annual statistical report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program, 2004. SSA Publication 13-11826. Released March 2006. Available: www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/di_asr/2004/index.html (accessed May 22, 2006).

SSAB (Social Security Advisory Board). 2006. Disability decisionmaking: Data and materials. Available: www.ssab.gov/documents/chartbook.pdf (accessed September 28, 2006).