6

The Listing of Impairments—Issues

The Social Security Administration (SSA) has asked the committee to make recommendations on how to improve the Listings, specifically addressing:

-

The value and utility of the current Listings for all users (claimants, SSA, health care professionals, state offices, and officials involved in the adjudication process)

-

Conceptual models for organizing the Listings, beyond the current “body systems” model at 20 CFR, Part 404, Subpart P, Appendix I

-

Processes for determining when the Listings require revision and criteria upon which to add new listings or remove old ones

-

Feedback mechanisms to continuously assess and evaluate the Listings for the purpose of improving consistency in application by all adjudicators throughout the country

-

Adaptability of the Listings, including methods to account for variable access to health care services (including diagnostics and pharmaceuticals) in determining whether an individual’s condition meets or equals the Listings

-

Methods to assess and quantify the effects of multiple impairments that may not individually cross the eligibility threshold (i.e., SSA’s “equivalence” concept)

-

Advisability of and methods for integrating functional assessment into the Listings

In subsequent discussions with the committee, SSA made clear that its concerns focus on three major areas:

-

The value and validity of the Listings as a screening tool

-

Use of functional criteria in the Listings

-

The process of updating and revising the Listings

THE LISTINGS AS A SCREENING TOOL

As discussed previously, the Listings are an administrative expedient. They are intended to make the decision-making process more expeditious and more efficient by identifying a portion of the allowance cases early in the process, without engaging in a time-consuming and resource-intensive inquiry into all of the issues that would otherwise be required.

Case-processing time is a major concern for SSA. The agency has made reduction of case-processing time one of its key goals for improved customer service, as reflected in the very first strategic objective in its Strategic Plan for FY 2006-FY 2011: “Make the Right Decision in the Disability Process as Early as Possible.” As SSA explains in the Strategic Plan (SSA, 2006:8-9):

In light of the significant growth in disability claims, the increased complexity of those claims, and the younger age of beneficiaries in recent years, the need to make substantial changes in the Agency’s disability determination process has become urgent. The length of time it now takes to process these claims is unacceptable. It places a significant physical, financial, and emotional burden on applicants and their families. It also leads to recontacts, and rehandling, thus placing an enormous drain on Agency resources.

According to the Agency’s service delivery assessment of the disability process conducted in 2001, persons pursuing their disability claims through all levels of Agency appeal wait an average of 1,153 days for that final decision….

The most significant external factors affecting the Social Security Administration’s ability to improve service to disability applicants are the dramatic growth of workloads and the increasing complexity of those workloads. Receipts will continue to rise as more baby boomers enter their disability-prone and then retirement years. With Disability Insurance rolls projected to grow 35 percent in the ten years ending 2012, the Social Security Administration cannot keep doing things the same way. Moreover, the type of impairments that have formed the basis for disability claims have changed over the years. The percentage of claims involving allegations of mental impairments has increased dramatically, particularly in the Supplemental Security Income program. Claims of disability involving mental impair-

ments raise particular administrative resource issues because they involve complex psychological issues and the evidence for these claims may be difficult to develop. The percentage of disability claims decided on the basis of vocational considerations rather than more readily determinable medical factors have also been increasing steadily. Thus, in addition to the growth in the number of claims, there has been a corresponding increase in the volume of complex claims.

Concerns with claim-processing time have also been an important factor in a major SSA initiative to revise the administrative review process. First announced in testimony before the Subcommittee on Social Security of the House Committee on Ways and Means on September 25, 2003, the plan proposed to implement a new “quick decision step” at the very beginning of the initial claim process, which would sort cases based on the existence of various medical conditions, and promote early identification of individuals who are obviously disabled (Barnhart, 2003). These new procedures are explained more fully in final rules published in the Federal Register on March 31, 2006 (71 FR 16424).

In meetings with the committee, SSA staff discussed the agency’s concerns about the declining utility of the Listings as a quick screening tool and the resulting increase in case-processing time and cost. They said that at one time the Listings were used to identify up to 80 percent of the allowance cases at the initial decision level. However, the Listings currently identify only about 50 percent of allowances (Sklar, 2005a). As a result of this decrease, fewer allowance cases are processed quickly, contributing to larger caseloads, longer average case-processing time, and higher case-processing costs.

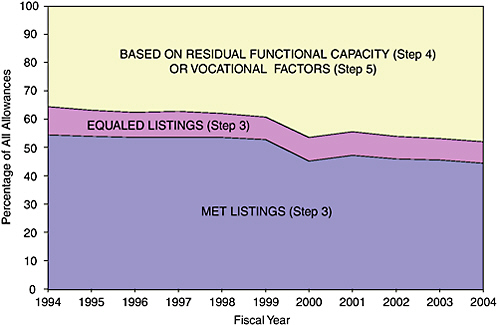

Historically, SSA has based most allowances on meeting or equaling the criteria in the Listings. In the earliest days of the disability program, the Listings accounted for more than 90 percent of the initial allowances (SSAB, 2003:7). As recently as the early 1980s, they were the basis for 70 to 80 percent of the initial allowances. Since then, use of the Listings has declined steadily, accounting for less than 60 percent of allowances in 2000 (SSAB, 2001:5). According to more recent data supplied to the committee by SSA, reliance on the Listings as the basis for allowance at the initial level has continued to decline. In 2004, the Listings accounted for 52 percent of the initial allowances (Figure 6-1).

Validity is another major concern. SSA does not want to expedite the decision process by approving some cases with less scrutiny if the screen is not able to distinguish between claims that meet the SSA definition of disability and those that do not. Neither type of error would be acceptable: either granting benefits to individuals who are not actually disabled or denying benefits to those who are disabled.

FIGURE 6-1 Basis for allowances at initial decision level, FY 1994 - FY 2004.

SOURCE: Data provided by SSA.

SSA began to investigate the validity of the Listings several years ago. In August 2001, researchers from the Disability Research Institute (DRI) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, under contract to SSA, investigated how the Listings might be validated (DRI, 2001). In their project description, they said:

The purpose of this project is to develop, or identify, appropriate criteria for use in validating SSA’s medical listings. Any criteria that are eventually developed must withstand scrutiny by experts representing the medical, functional, vocational, research, legal, and political arenas (DRI, 2001).

As a result of their investigation, the DRI researcher concluded that because the “Listings are not a test, per se, the concepts of test validation require extension to validating a component of a larger disability determination process” (DRI, 2001:1). They suggested a four-part validation strategy relying on:

-

Assessment of face and content validity by evaluating the extent to which the Listings reflect current medical and diagnostic tests to establish actual impairments

-

Assessing predictive validity by comparing the number of people who are able to work among those who meet a listing with the number who are able to work who do not meet the listing

-

Assessment of concurrent validity by examining whether meeting a listing is a significant predictor of not engaging in substantial gainful activity (SGA)

-

Assessment of construct validity by examining the congruence of decisions made at step 3 with decisions that would be made using the medical/ functional criteria at step 5

This investigation was cited approvingly on two occasions by the Government Accountability Office (GAO); first, as an example of SSA’s research efforts to explore how medical advances and social changes require the disability programs to evolve (GAO, 2002:12); and again when adding SSA’s disability programs to its list of high-risk government programs:

While SSA has not fully updated its disability criteria, it has started a number of studies that recognize that medical advances and social changes require the disability program to evolve. SSA has funded a project through its Disability Research Institute (DRI) to design a study assessing the validity of its medical criteria as measures of disability … (GAO, 2003:9).

This effort was not continued after the initial report.

FUNCTIONING IN THE LISTINGS

The first Listings were brief and focused on clinical, diagnostic criteria. However, as the Listings have evolved, they have come to apply to a much more diverse group of applicants. They have become more elaborate and more complex, incorporating additional criteria for observations, specific signs, symptoms and laboratory findings, as well as functional outcomes. SSA has asked the committee to look into the use of functional criteria in the Listings.

SSA staff told the committee that the Listings were originally intended to be based on “medical” criteria, but they now rely more on functional criteria (Sklar, 2005a). The president of the National Council of Disability Determination Directors (representing many of the state agencies that make disability decisions on behalf of SSA) told the committee that using functional criteria in the Listings changed the Listings from “objective and simple” to “complex and subjective,” causing inconsistency in decisions and increased case-processing time. He said that SSA began moving to functionally based Listings in 1985, when it published a major revision to the adult mental disorders listings. Before then, he said, the Listings only

required documentation of a diagnosis, or a diagnosis plus specific clinical findings. He attributed the decline in use of the Listings to allow claims to the addition of more functional criteria that are harder to apply, observing that this creates additional work for the Disability Determination Services. He pointed to the most recent revisions to the musculoskeletal disorders listings (published on November 19, 2001, at 66 FR 58010-58046) as especially problematic (Marioni, 2005).

Although it is true that the earliest Listings (in the 1950s) were based largely on clinical and diagnostic criteria, functional criteria came into widespread usage well before 1985. The July 4, 1967, Listings (the oldest version that is readily available)1 contained a variety of functional criteria. There were explicit measures of functional capability, such as:

-

measurement of breathing capacity (respiratory impairments)

-

measurement of visual acuity, visual efficiency, or visual fields (vision impairments)

-

measurement of speech discrimination or hearing (hearing impairments)

-

measurement of joint function (musculoskeletal impairments)

There were also more subjective functional indicators, such as:

-

“History of joint pain and swelling in two or more major joints, and morning stiffness persistent on activity” (rheumatoid arthritis)

-

“With well developed tremor, rigidity, and impairment of mobility” (Parkinson’s disease)

-

“Advanced limitation of use of hands” (scleroderma)

-

“… nocturnal episodes which show residuals interfering with activity during the day” (epilepsy)

-

“… marked constriction of daily activities and interests, deterioration in personal habits, and seriously impaired ability to relate to other people” (functional nonpsychotic disorders)

The mental disorders listings that were in use prior to the 1985 revision were already largely based on functional indicators of impairment severity.2 For each of the major categories of mental disorders, the impairment listings consisted of a set of criteria that established the existence of the impairment

(i.e., diagnostic criteria), followed by a set of functional criteria to establish impairment severity. To meet the listing, the documented impairment had to result in persistence of “marked restriction of daily activities and constriction of interests and deterioration in personal habits and seriously impaired ability to relate to other people.” (The criterion of deterioration of personal habits was not included for functional psychotic disorders.) Thus, the 1985 change was not a switch from “clinical” to “functional” criteria (or from “objective” to “subjective” standards) but, rather, a change from one set of functional criteria to another. That change was prompted by the Disability Benefits Reform Act of 1984, a law that directed SSA to revise the mental listings to more realistically evaluate the ability to engage in SGA in a competitive workplace (Collins, 1985). The functional criteria that were adopted in 1985 focused on functional outcomes that had a more direct relationship to the workplace, as illustrated in Table 6-1.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the Listings, which were originally based on little more than diagnostic criteria, now include a wide variety of both clinical and functional measures to confirm not only the existence of a particular medical condition (i.e., a diagnosis of pathology), but its degree of severity (i.e., impact of diagnosed condition on function of the claimant). SSA staff told the committee that including functional criteria in the Listings has several advantages over the use of solely clinical criteria (Eigen, 2005). They said the functional Listings criteria:

-

More realistically represent the definition of disability, which is based on functional limitations.

TABLE 6-1 Comparison of Mental Impairment Severity Measures

|

Pre-1985 Functional Indicators |

1985 Functional Indicators |

|

Restriction of daily activities |

Restriction of activities of daily living |

|

Constriction of interests |

Difficulty maintaining social functioning |

|

Deterioration of personal habits |

Deficiencies of concentration, persistence, or pace resulting in failure to complete tasks in a timely manner (in work settings or elsewhere) |

|

Impaired ability to relate to other people |

Episodes of deterioration or decompensation in work or work-like settings that cause the individual to withdraw from that situation or to experience exacerbation of signs and symptoms (which may include deterioration of adaptive behaviors) |

|

SOURCES: POMS DI 34132.003; 50 FR 35038-35070. |

|

-

Allow SSA to devise more listings. Often there are no clinical findings that correlate with impairment severity, and the only way to devise a listing is to base it on functional indicators of severity. The only other alternative is to have no listing at all.

-

Permit more allowance cases to be screened in at the Listings step.

-

Permit greater parity among different listings.

-

Make it possible to give meaningful consideration to an individual’s symptoms and to the medical opinions of there medical treatment sources.

-

Allow better evaluations of combinations of impairments.

LISTINGS REVISION PROCESS

Federal agencies, such as SSA, keep the public informed of their program rules and enable public participation in the rulemaking process under the provisions of the Administrative Procedures Act (APA). Agencies notify the public of substantive rules they propose to adopt by publishing “notices of proposed rule making” (NPRMs) in the Federal Register and allow members of the public an opportunity to present their views before adopting final rules. The Listings, being substantive SSA rules, are established and revised under the provisions of the APA for public notice and comment.

SSA recently began including additional steps in rulemaking for the Listings, beyond the required APA notice and comment process. The agency now publishes “advance notices of proposed rulemaking” in the Federal Register, seeking early input from the public on revisions to the Listings before it proposes any specific new rules. SSA is also conducting outreach meetings across the country, soliciting additional public comment and inviting input from a variety of sources, including physicians and other subject-matter experts, advocacy groups, and patients with the specific diseases or impairments under consideration. It holds these meetings before proposing any new rules (Sklar, 2005b).

SSA described these new procedures in regulations published on March 31, 2006, Administrative Review Process for Adjudicating Initial Disability Claims (71 FR 16425):

As part of this effort, we have implemented a new business process to streamline the updating of our medical listings….

We have taken steps to increase outside participation in the development of our medical listings. As a first step, we now publish an advance NPRM to encourage members of the public to comment on the current medical criteria and to provide suggestions on how the medical criteria could be updated.

In fiscal year 2005, we published advance notices involving impairments related to the respiratory and endocrine systems, growth impairments, and

neurological impairments, as well as portions of the special senses (hearing impairments and disturbances of the labyrinthine-vestibular function). We also proposed the development of a new listing covering language and speech impairments.

Following up on the advance notices, we have held numerous public outreach events. These sessions provide an opportunity for medical experts, claimants, and advocates to comment on our current policies and to advise us on the future content of the medical criteria.

SSA also told the committee that it is making regulatory updates to the Listings more frequently now. Few listings were revised between 1985 and 2005. According to GAO, SSA’s listing update activities had been curtailed in the mid-1990s due to staff shortages, competing priorities, and lack of adequate research (GAO, 2002). However, as of August 2005, SSA had completed final rules updating 3 of 14 body systems, and it intends to finish a complete update of all the Listings by July 2007. SSA has also begun using an expedited internal regulatory development and clearance process, which is intended to reduce the time it takes to develop and publish a final rule by up to three and one-half months. However, the process still requires a minimum of 13 months to complete (Sklar, 2005b).

Like all other substantive agency policy, the specific criteria for all the Listings are published as regulations, using the APA regulatory process. However, SSA publishes additional guidance for its adjudicators in the form of agency rulings, called Social Security Rulings (SSRs). SSRs are agency policy interpretations, as opposed to substantive agency rules. Although they do not have the force and effect of the law or regulations, they are binding on all components of SSA (20 CFR 402.35(b)(1)). Recent examples of SSRs include:

-

SSR 03-2p—Evaluating Cases Involving Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome/Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. This ruling provides guidance on evaluating Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy/Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, for which there is no listing.3

-

SSR 02-1p—Evaluation of Obesity. This ruling provides guidance on evaluation of obesity. Obesity had been deleted from the Listings on October 25, 1999.4

-

SSR 99-2p—Evaluating Cases Involving Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. This ruling provides guidance on evaluating Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, for which there is no listing.5

|

3 |

Available at: www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/01/SSR2003-02-di-01.html. |

|

4 |

Available at: www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/01/SSR2002-01-di-01.html. |

|

5 |

Available at: www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/01/SSR99-02-di-01.html. |

When deciding whether to revise the Listings, SSA considers such things as specific legislation, court decisions, and congressional interest. The most important factor may be advances in medicine. It also considers its own adjudicative experiences and input from the public. To develop appropriate revisions, SSA relies on information from a variety of sources, including inhouse medical experts, individual subject-matter experts from outside the agency, literature reviews, and contracted research. It receives input from agency personnel who use and apply the Listings and through the quality assurance process, and it sometimes conducts internal case reviews. SSA also receives input from the public, other government agencies, professional associations, and advocacy organizations. However, SSA does not use formal advisory committees, which are established under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA), or any similar type of panel or group. In the past, SSA has assembled groups of experts to advise SSA on revisions to the Listings. However, they were not formal advisory committees as required by FACA and they are no longer used (Lively and Sklar, 2006).

REFERENCES

Barnhart, J.A. 2003. Statement of The Honorable Jo Anne B. Barnhart, commissioner, Social Security Administration. Testimony before the Subcommittee on Social Security of the House Committee on Ways and Means, September 25, 2003. Available: waysandmeans.house.gov/hearings.asp?formmode=view&id=761&keywords=Barnhart (accessed May 12, 2006).

Collins, K. 1985. Social Security Disability Benefits Reform Act of 1984: Legislative history and summary of provisions—Includes appendices. Social Security Bulletin. April, 1985. Available: www.findarticles. com/p/articles/mi_m6524/is_n4_48/ai_3716220/print (accessed May 17, 2006).

DRI (Disability Research Institute). 2001. Research approaches to validation of SSA’S medical listings: Medical listings validation criteria. Available: www.dri.uiuc.edu/research/p01-02c/default.htm and www.dri.uiuc.edu/research/p01-02c/related_project_validation_p01-02c.doc (accessed September 30, 2006).

Eigen, B. 2005. Listings issues. Oral presentation to the IOM Committee on Improving the Social Security Disability Decision Process. August 4, 2005. (PowerPoint presentation is in a public access file and available from the IOM on request.)

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2002. Social Security Administration: Fully updating disability criteria has implications for program design. Testimony before the Subcommittee on Social Security, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives. GAO-02-919T. July 11, 2002. Available: www.gao.gov/new.items/d02919t.pdf (accessed November 17, 2005).

GAO. 2003. Major management challenges and program risks. Social Security Administration. Available: http://www.gao.gov/pas12003/d03177.pdf.

Lively, C., and G. Sklar. 2006. How SSA revises the Listings. Presentation to the IOM Committee on Improving the Social Security Disability Decision Process. January 30, 2006. (PowerPoint presentation is in a public access file and available from the IOM on request.)

Marioni, A.J. 2005. Untitled oral presentation to the IOM Committee on Improving the Social Security Disability Process. January 31, 2005.

Sklar, G. 2005a. Medical policy and medical expertise in SSA’s disability programs. Oral presentation to the IOM Committee on Improving the Social Security Disability Decision Process. January 31, 2005. (PowerPoint presentation is in a public access file and available from the IOM on request.)

Sklar, G. 2005b. Committee tasks to improve the Listings. Oral Presentation to the IOM Committee on Improving the Social Security Disability Decision Process. August 4, 2005. (PowerPoint presentation is in a public access file and available from the IOM on request.)

SSA. 2006. Strategic plan FY 2006–FY 2011. January 2006. Washington, DC. SSA Publication 04-002. Available: www.ssa.gov/strategicplan2006.pdf (accessed May 20, 2006).

SSAB (Social Security Advisory Board). 2001. Charting the future of Social Security’s disability programs: The need for fundamental change. Washington, DC: SSAB. Available: www.ssab.gov/Publications/Disability/disabilitywhitepap.pdf (accessed November 17, 2005).

SSAB. 2003. The Social Security definition of disability. Washington, DC: SSAB. Available: www.ssab.gov/documents/SocialSecurityDefinitionOfDisability_002.pdf (accessed November 17, 2005).