5

The Evaluation of PTSD Disability Claims

This chapter addresses the evaluation of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compensation and pension (C&P) claims by the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). It contains a brief summary of the means by which veterans may obtain compensation for service-related disabilities, background on the claims evaluation process, and the committee’s response to elements of the charge related to these evaluations.

VETERANS’ DISABILITY COMPENSATION

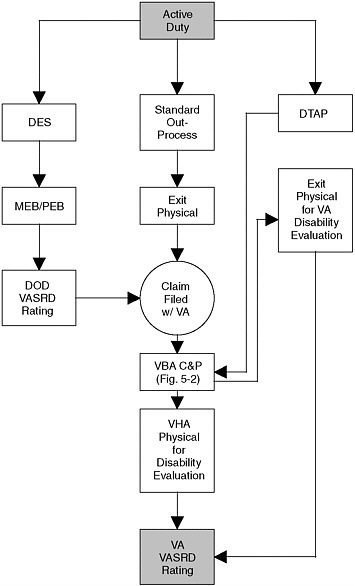

Veterans receive disability compensation related to their military service via three basic processes: (1) through the Department of Defense (DOD) Disability Evaluation System (DES); (2) through the federal Transition Assistance Program; and (3) by filing a claim with the VA subsequent to separation from service. Figure 5-1 illustrates the pathways to disability compensation afforded by the programs.

The Department of Defense Disability Evaluation System

The core functions of the DOD DES are to ensure that the military force remains fit and to provide compensation for those service members on regular active duty, in the Reserve, or in the National Guard whose military careers are cut short by illness or injury before they meet time-in-service requirements for retirement benefits eligibility. DOD disability benefits are

FIGURE 5-1 Military disability compensation pathways.

NOTE: The TAP is left out of this flowchart but is part of all three pathways.

granted to “compensate for the loss of a military career” (DOD, 2006). To qualify for DOD disability compensation, a service-incurred or service-aggravated illness or injury must render a service member permanently unfit to perform the “duties of office, grade, rank, or rating” and must not be the result of “misconduct or willful neglect” (Howard, 2006). Disability is determined according to the effects that a condition has on a service member’s ability to perform according to military occupational specialty.

As a rule,1 a disability rating is based solely on the “unfitting” condition (DOD, 1996).

DOD compensation awards are based both on disability ratings and on time in service. The compensation may be awarded as a lump-sum severance payment or as monthly payments2 (GAO, 2006). The standard for the determination of DOD disability ratings—DOD Instruction 1332.39; Title 10, United States Code Chapter 61—is the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Schedule for Rating Disabilities (VASRD) (DOD, 1996). But while the VASRD, as described in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 38, Part 4 (38 CFR, Part 4), provides the standard for DOD disability ratings, the DOD considers absolute application of VASRD provisions incompatible with its mission. Thus, the DOD differs from the VA both in how it views the purpose of disability compensation and in how it implements the VASRD. Furthermore, within the DOD variation exists among service branch DESs. DOD regulations are consistent across the different branches, in that they require each DES to have a medical evaluation boardand a physical evaluation board, but both the boards and the appeals processes are constituted differently from branch to branch (GAO, 2006).

Concurrent Receipt

When a service member is granted monthly DOD disability compensation, officially referred to as permanent disability retirement, he or she is also entitled to be considered for disability compensation through the VA. Until January 2004 permanent disability retirement pay was, by statute, reduced by the dollar amount of VA disability compensation received (Henning, 2006). But Public Law 108-136, in addition to altering other DOD retirement payment policies,3 authorized a 10-year phase-out of the reduction of military retirement due to VA compensation and allowed concurrent receipt of VA and DOD compensation for those veterans with a combined disability rating at or above 50 percent (DOD, 2006). As part of the military retirement offset phase-out, on January 1, 2005 veterans rated

at 100 percent by the VA became entitled to their full military retirement pay without any offset of VA disability compensation. Those who are not rated at 100 percent according to the schedule of ratings but who receive 100 percent VA compensation under the provision of individual unemployability (IU) are slated to have their full military retirement entitlement restored beginning in October 2009 (DOD, 2006; Henning, 2006).

Transition Assistance Program

TAP is a joint federal program of the DOD, VA, and the Department of Labor designed to help service members make the initial transition from military service to the civilian workforce. It was first implemented in 1990. Military members who have served at least 180 days on active duty are eligible to participate in TAP. Disabled service members are eligible regardless of time served (GAO, 2005). TAP has four core elements that are intended to help service members adjust successfully to civilian life. Of the four components, VA administers two: the Disabled Transition Assistance Program (DTAP), which offers briefings about the VA’s vocational rehabilitation programs, and Benefits Delivery at Discharge (BDD), where VA representatives start processing disability claims before the service member leaves active service.

TAP and DTAP briefings

All service members who attend a TAP briefing receive a general overview of VA benefits and services. Benefits briefings cover education, insurance, and home loan guaranty entitlements—generally, GI Bill-related items4—and are offered to active-duty members at 215 military installations worldwide.5 The majority of active-duty members can participate in TAP as early as one year before leaving service as a standard component of military out-processing. Retiring service members are eligible for TAP two years before separation (GAO, 2005). Active-duty service members are usually offered TAP at their assigned duty stations. It is less clear how activated Reserve personnel and National Guard personnel access TAP, as demobilization of these personnel takes place in a few days and occurs in areas remote from places of employment or residence (GAO, 2005).

DTAP briefings are provided to service members who are separating from active duty with a disability that may be related to their service.

They are focused on the VA’s Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment Program. While briefings are typically held in a group setting, special provisions can be made for service members who are hospitalized, convalescing, or receiving outpatient treatment (U.S. Army, 2006). Representatives from veterans services organizations can also conduct TAP and DTAP briefings (VBA, 1999).

Disabled Transition Assistance Program and Benefits Delivery at Discharge

The VA has two separate programs that allow personnel to initiate disability claims while still on active duty. The first program, DTAP, “offers [to disabled service members] personalized vocational rehabilitation and employment assistance at major military medical centers where such separations occur and at other military installations” (DVA, 2005a). The second program, BDD,6 offers assistance to “service members at participating military bases with development of VA disability compensation claims prior to their discharge” (DVA, 2005a). Personnel with access to BDD have the opportunity to have their predischarge or exit physicals conducted according to VA protocols by DOD examiners, VA examiners, or contracted examiners (DVA, 2005a). There is an official Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the DOD and the VA for the BDD examination process. MOUs are also developed at the local level. These agreements discuss the exchange of information and resources between the DOD and the VA and also seek to ensure that examining clinicians have access to both service medical records and VA examination protocols. It is unclear if BDD replaces DTAP in certain circumstances and how DBB and DTAP eligibility, access, and participation vary.

Ideally, when service members attend TAP briefings, they receive an overview of the vocational rehabilitation program and its eligibility requirements. If they believe that they may be eligible for vocational rehabilitation and express an interest in that program, they can “self-select” into DTAP. They are then given the more in-depth briefings on vocational rehabilitation and can begin the evaluation process.

Barriers to participation in these transition-assistance programs do exist. Members of the Reserves and National Guard, for example, often participate in more than a dozen demobilization activities, including a physical examination, in the matter of just a few days (GAO, 2005), and this gives them little opportunity to participate in a transition-assistance program as well. Furthermore, members of the Reserves and National Guard were

found to be less likely to have been briefed in transition on “certain education benefits and medical coverage requir[ing] service members to apply while they are still on active duty,” and some of those who had received briefings remained unaware of the limited application window for these benefits (GAO, 2005). Reserve and National Guard personnel on medical holdover status do not have the same access to TAP/DTAP programs that active duty personnel on holdover status do because of variation in the processing of military orders (VDBC, 2006). According to the GAO, no “data are available regarding participation in the VA components of TAP,” and “[r]egarding DTAP, no data are available to determine the number of eligible individuals, and VA’s records do not distinguish the number who participate in the component from the total of all recipients of VA outreach briefings” (GAO, 2005).

No matter what disability rating has been determined by the DOD, if a veteran desires compensation from VA, he or she must submit a separate application for disability benefits and have the VA rate their condition all over again. It is possible for a service member found fit for duty by the DOD with respect to a particular condition to be awarded disability compensation by the VA for the same condition. It is even possible to go “from 100 percent fit [for] duty [according to DOD] to 100 percent disabled” according to the VA for the same condition (Howard, 2006).

VA Disability Claims Adjudication

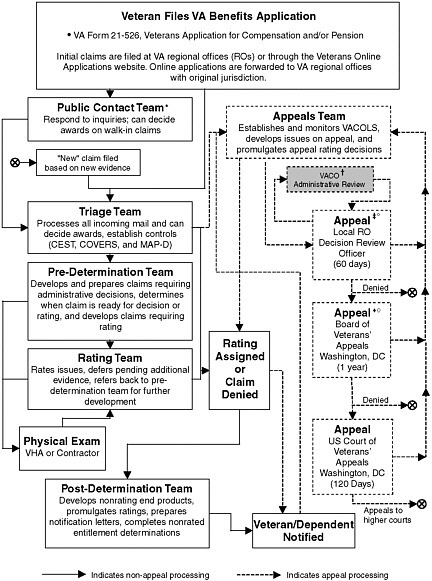

Veterans’ disability benefits claims may go through many stages of processing and review before a decision is made. Figure 5-2 summarizes this process.

VBA Claims Processing

A veteran initiates the claims process by filing VA Form 21-526 with a VA Regional Office (VARO). An applicant may also file an application for benefits through the Veterans’ Online Applications website. Online applications are automatically forwarded to the VARO with original jurisdiction. By law (codified in 38 CFR §3.159), VA must provide claimants certain support in the development of these claims. Assisting with the acquisition of evidence, including requests for evidence from pertinent sources, is a major part of VA’s duty to assist the veteran (DVA, 2004).

Claims are processed at VARO Veteran Service Centers (VSCs). According to the Veterans Benefits Administration Adjudication Procedure Manual M21-1MR (VBA, 2005), each VSC using the Claims Process Improvement (CPI) model is composed of six teams. The composition and function of these teams is summarized in Table 5-1.

FIGURE 5-2 Veterans Benefits Administration Claims Process (CPI model).

*Team also makes post-rating contacts; †Not the only type of special review, but the only one that can be initiated by the claimant’s representative; ‡DRO may not reduce existing rating; ° VA Form 9; ♦May affirm, modify, reverse or remand; ◊VA Form 8.

Although regional offices have some discretion in assignments to the teams, a triage team will generally consist of about eight members and will include the following of employees: coach, assistant coach, rating veteran service representatives (RVSRs), veterans service representatives (VSRs),

TABLE 5-1 Veteran Service Center Teams

|

Team |

Functions |

|

Triage |

|

|

Predetermination |

|

|

Rating |

|

|

Postdetermination |

|

|

Appeals |

|

|

Public Contact |

|

|

SOURCE: VBA manual M21-1MR, part III, subpart I, chapter 1 (2005). |

|

senior VSR, claims assistant, file bank coach, and file clerk/program clerk (VBA, 2005).7 Beyond the management of incoming mail and related files, the triage team is authorized to process those claims requiring only minimal review of the evidence. The VBA M21-1MR does not provide details on what is considered to be a “minimal review.”

The predetermination team manages claims requiring administrative decisions and determines when a claim is ready for a decision or rating. If a clinical examination8 is required to adjudicate a claim, the team can order one to be performed. Examinations can be requested by more than one team/team member.

VSRs in the Predetermination Team have primary responsibility for requesting examinations. A RVSR may provide guidance on examination requests as necessary. RVSRs also have authority to directly request examinations. The Veterans Service Center Manager (VSCM) can authorize an examination in any case in which s/he believes it is warranted (VBA, 2005).

The committee was unable to determine the percentage of disability claims adjudicated without a clinical evaluation, as VBA does not track these data. The predetermination team has as many as eight team members, with the same titles and pay grades as triage team members.

|

7 |

Details of the federal classification and job grades listed in parentheses can be found on the U.S. Office of Personnel Management website at http://www.opm.gov/fedclass/. |

|

8 |

Information on C&P clinical examinations is presented in Chapter 4. |

A rating team consists of a coach, assistant coach, rating VSRs, and a claims assistant (VBA, 2005). The rating team is responsible for rating claims that have been deemed “ready to rate” by the predetermination team. The rating team may also receive claims directly from the triage, appeals, or public contact teams.

The membership of the postdetermination team has the same general composition as the rating team, with fewer RVSRs and more VSRs. This team receives developed claims from which it promulgates ratings and prepares notification letters. A veteran or a representative acting on her or his behalf can file an appeal to a disability determination or rating by requesting a reevaluation. The appeals team—coach, decision review officer, senior VSR, RVSR, VSR, claims assistant, and file clerk/program clerk—oversees this process, which consists of several stages.9 Initially, if a claim is denied or a veteran disagrees with the level of the disability level awarded, she or he files a notice of disagreement. The claimant is then contacted by a Decision Review Officer (DRO) and is given the choice to have that person conduct a de novo (new) review. If the claimant is not satisfied with the DRO’s decision or chooses otherwise, then s/he can file a substantive appeal to the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). If the BVA’s decision fails to resolve the claimant’s concerns, s/he can file a lawsuit in the U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims. A veteran can also reopen a claim based on new and material evidence and begin the process anew.

In theory, a claim that has been processed and then appealed at the local regional office level could have 40 VBA rating-team members and a U.S. Army and Joint Services Records Research Center (JSRRC)10 representative involved in the rating decision, assuming the VARO was fully staffed according to the CPI model.

While detailed requirements of knowledge, skills, and abilities are published for each rating-related position, VA regulations allow for the delegation of responsibility for nearly all of these positions. It is not known how staffing varies by VSC or whether the CPI model is the norm or the gold standard.

Complete tracking of the VBA personnel chain involved in the adjudication process is complicated by the repeated use of titles across teams, by the flexible assignment of responsibilities within and among teams, and by the many variations in local VARO policies and procedures. An additional factor that makes review difficult is that understaffed VAROs are

authorized to “broker” claims to other regions for processing. Therefore, this summary has been provided as a general reference and not an absolute accounting of the VBA claims adjudication process.

The benefits application process is intended to be nonadversarial and supportive to claimants. As noted elsewhere, VA’s duty to assist includes helping veterans to gather evidence to support their claims, including provision of VA records and facilitation of requests for information from DOD and other sources. If a veteran disputes a determination, the initial stages of appeals process are conducted without anyone representing an opposing viewpoint and with consideration of all possible theories of entitlement (Violante, 2004). In addition, “[w]hen, after careful consideration of all procurable and assembled data, a reasonable doubt arises regarding service origin, the degree of disability, or any other point, such doubt will be resolved in favor of the claimant” (38 CFR §3.102). It is only when an action reaches the U.S. Court of Veterans’ Appeals that it takes on the characteristics of a formal legal proceeding, with the potential for presentation of evidence contrary to the claimant’s assertions or interest.

Nonetheless, the process has been described as “complex, legalistic, and protracted” and as particularly difficult for veterans with PTSD to manage because of the stresses and uncertainties involved (Sayer et al., 2005). The situation may be exacerbated in some circumstances by skeptical and cynical attitudes toward PTSD compensation-seeking veterans among certain VA staff (Sayer and Thuras, 2002; Van Dyke et al., 1985).

The VASRD Rating Process11

The primary task of a rater is to assign one more ratings of disability based on the input received from the veteran, the clinician, and other members of the rating team. The VA disability rating depends on a complex assessment of many factors, and numerous variables play a role in determining the amount of the disability awarded. The VASRD does not take into account military rank, tenure, sex, or wartime cohort. The VA Office of the Inspector General did, however, find that variations in award ratings were correlated with certain factors, including (DVA, 2005b):

-

enlisted (higher award) versus officer status;

-

military retiree (higher award) versus nonmilitary retiree;

-

attorney representation (higher award);

-

number of veterans applying for benefits (higher number, higher award);

-

period of service (Vietnam veterans receive highest awards);

-

branch of service (Marine Corps veterans receive highest award); and

-

rater experience (more experience, higher award).

The same report also found that a lack of time to develop claims often leads to inadequate development of claims or to determinations that could support two different ratings for the same case (DVA, 2005b).

In addition, there are aspects of how disabilities are rated that may influence the amount of an award. For example, some disabilities, especially those based on self-reports, are more difficult to rate, and this may create a lack of reliability in the award decisions. The validity of currently employed instruments has also been called into question, as there have been substantial advances in fields related to disability assessment in the context of disease, illness, function, impairment, and rehabilitation since the establishment of the VASRD. These issues were recognized by a 2005 VA review (DVA, 2005b):

Our analysis of rating decisions shows that some disabilities are inherently more susceptible to variations in rating determinations. This is attributed to a combination of factors, including a disability rating schedule that is based on a 60-year-old model and some diagnostic conditions that lend themselves to more subjective decision making…. The VA disability compensation program is based on a 1945 model that does not reflect modern concepts of disability. Over the past 5 decades, various commissions and studies have repeatedly reported concerns about whether the rating schedule and its governing concept of average impairment adequately reflects medical and technological advancements and changes in workplace opportunities and earning capacity for disabled veterans. Although some updates have occurred, proponents for improving the accuracy and consistency of ratings advocate that a major restructuring of the rating schedule is long overdue (p. vi).

The assessment of psychiatric illness is particularly challenging. The VA Inspector General’s 2005 review of state variances in disability compensation payments found that mental disorders—including PTSD—had the fourth highest variability in disability rating of the 15 body systems (DVA, 2005b). In contrast, ratings that can be independently validated (amputation, for example) were highly reliable and consistent.

The 2005 VA report also found that the number of PTSD cases receiving disability awards and the amounts of the awards given in these cases are both growing. From fiscal year (FY) 1999 to FY 2004 the number and

percentage of PTSD cases increased significantly. While the total number of all veterans receiving disability compensation grew by 12.2 percent, the number of PTSD cases grew by 79.5 percent, from 120,265 cases in FY 1999 to 215,871 cases in FY 2004. During the same period, PTSD benefits payments increased 148.8 percent, from $1.7 billion to $4.3 billion. By contrast, compensation for all other disability categories increased by 41.7 percent. While veterans being compensated for PTSD represented 8.7 percent of all compensation recipients, they received 20.5 percent of all compensation payments (DVA, 2005b).

Rater Training

VBA manages and executes a national training program for VSRs and RVSRs called Challenge. The program involves a combination of on-the-job training, regional classroom training, and computer-assisted learning. It is administrated on a VSC level and, while variations exist, it generally follows the schedule summarized below.

When a VSR (or RVSR) is hired, the person is expected to undergo an orientation to his or her new job and to the regional office, learning the basics of the position, such as the workflow, rules of law, operational tools, and the like. This initial phase is intended to last about six months. Then the trainee is scheduled to attend three weeks of centralized classroom instruction on all major components of the job. Instructors include both C&P service experts and experienced technicians from the field. When trainees return from the classroom, they are given additional on-the-job training, and they work through a series of video-based structured learning modules that constitute the Training Performance and Support Systems (TPSS) program.12 Initial rater training lasts approximately two years and includes a rotation on the postdetermination team. After mastering the tasks on the predetermination and postdetermination teams, the rater may work on a public contact team. The next level in the training hierarchy is rotation to the triage and appeals teams (DVA, 2005b; R.J. Epley, personal communication, 2006; Walcoff, 2006).

In 2001 the GAO cited “lack of time for training due to workload pressures” (p. 8) as the greatest barrier to field-wide use of TPSS training. A 2005 survey of VBA rating-team members by the VA Office of the Inspector General found that the two greatest issues in the rating process were, in order, the “perceived emphasis on production at the expense of quality” and “the need for more and better training” (OIG, 2005, p. 61). Regional office employees said that because of the complexity and variation in individual

claims, on-the-job training is the most effective means of training members of rating teams (GAO, 2001).

ISSUES REGARDING PTSD DISABILITY RATING CRITERIA

VA asked the committee to address several issues related to the rating criteria currently used to rate disability for veterans with service-connected PTSD. These included whether the current rating schedule regulation, which applies to all mental disorders, is appropriate for evaluating PTSD, what criteria should be included in any revised schedule, and whether there are other evaluation methods in existence that would be more appropriate than the one VA currently uses. In addition to addressing these issues, the committee also offers some comments on the training of raters.

The section begins with discussions of three topics—the rating criteria for PTSD and other conditions, trends in disability compensation, and the considerations underlying how other disability-benefits systems evaluate mental disorders—that lay the groundwork for the committee’s findings and conclusions.

The VASRD Rating Criteria for PTSD and Other Conditions

Table 5-2 summarizes the VASRD rating criteria for several dozen conditions, with a particular focus on those that, like PTSD, are symptom-based or have a relapsing/remitting course. As the table illustrates, there is considerable variability among the conditions in how percentage ratings are determined. The variability is manifested in several ways, including:

-

The full range of disability ratings percentages (e.g., 10 percent, 20 percent, 30 percent, … , 100 percent) is seldom used. Instead, it is typical to employ somewhere between one13 and three to five categories.

-

Within a specific disorder, equivalent increases in percentage ratings do not necessarily correspond to equivalent increases in disease severity (that is, going from 10 to 30 percent may represent a very different change in disease severity than going from 30 to 50 percent or from 70 to 90 percent).

-

The degree of disability represented by a particular rating level (30 percent, for example) does not appear to be consistent across different disorders.

These issues may be traced to several factors. First and most important,

TABLE 5-2 VASRD Disability Percentage Ratings for Selected Conditions

|

Condition |

10% |

|

20-30% |

|

40-50% |

|

60-70% |

100% |

|

Mental disorders |

OSIa due to mild or transient symptoms which decrease work efficiency and ability to perform occupational tasks only during periods of significant stress; or symptoms controlled by continuous medication |

30 |

OSI with decrease in work efficiency and intermittent occupational impairment due to such symptoms as depressed mood; anxiety; suspiciousness; panic attacks (weekly or less often); chronic sleep impairment; mild memory loss |

50 |

OSI with reduced productivity due to such symptoms as: flattened affect; disordered speech; panic attacks ≥ once a week; impaired memory and judgment; disturbed motivation and mood; difficulty in establishing and maintaining relationships |

70 |

OSI, with major deficiencies in most areas, such as work, school, family, judgment, thinking, or mood, due to such symptoms as suicidal ideation; obsessional rituals; disordered speech; near-continuous panic or depression affecting ability to function; impaired impulse control; neglect of personal appearance; etc. |

Total OSI, due to such symptoms as: gross impairment in thought; persistent delusions or hallucinations; grossly inappropriate behavior; persistent danger of hurting self or others; intermittent inability to perform ADL; disorientation to person/time/place |

|

Fibromyalgia |

Requires continuous medication for control |

20 |

Episodic, but present more than one-third of the time |

40 |

Constant, or nearly so, and refractory to therapy |

|

|

|

|

Arthritis, degenerative (in absence of limitations in motion) |

X-ray evidence in ≥ 2 joints |

20 |

X-ray evidence in ≥ 2 joints; occasional incapacitating exacerbations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intervertebral disc syndrome (based upon incapacitating episodes past 12 months)b |

≥ 1 wk (< 2 wk) |

20 |

≥ 2 wk (< 4 wk) |

40 |

≥ 4 wk (< 6 wk) |

60 |

≥ 6 wk |

|

|

Peripheral vestibular disorders (requires objective vestibular findings) |

Occasional dizziness |

30 |

Dizziness, with occasional staggering |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meniere’s syndrome |

|

30 |

Hearing impairment with vertigo < once a month |

|

|

60 |

Hearing impairment with attacks of vertigo and cerebellar gait 1-4 times/mo. |

Hearing impairment with attacks of vertigo and cerebellar gait ≥ once a week |

|

Loss of auricle |

Deformity of one, with loss of ≥ 1/3 |

30 |

Complete loss of one |

50 |

Complete loss of both |

|

|

|

|

Chronic fatigue syndromeb |

Waxes and wanes, resulting in periods of incapacitation of ≥ 1 (< 2) wk/yr |

20 |

Nearly constant and restricts routine daily activities by < 25% of pre-illness level; or which waxes and wanes, resulting in periods of incapacitation of ≥ 2 (< 4) wks/yr |

40 |

Nearly constant and restricts routine daily activities to 50 to 75% of pre-illness level; or which waxes and wanes, resulting in periods of incapacitation of ≥ 4 (< 6) wks/yr |

60 |

Nearly constant and restricts routine daily activities to < 50% of pre-illness level, or; which waxes and wanes, resulting in periods of incapacitation of ≥ 6 weeks/yr |

Nearly constant and so severe as to restrict routine daily activities almost completely and which may occasionally preclude self-care |

|

Condition |

10% |

|

20-30% |

|

40-50% |

|

60-70% |

100% |

|

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

Exacerbations once or twice a year or symptomatic during the past 2 years |

|

|

|

|

60 |

Exacerbations lasting a week or more, 2 or 3 times per year |

Acute, with frequent exacerbations and severe impairment of health |

|

HIV-related illness |

Symptomatic, T4 cell = 200-499, and on approved medication(s); or with depression or memory loss & employment limitations |

30 |

Recurrent constitutional symptoms, intermittent diarrhea, and on approved medication(s); or minimum rating with T4 < 200, or hairy cell leukoplakia, or oral candidiasis |

|

|

60 |

Refractory constitutional symptoms, diarrhea, and pathological weight loss; or minimum rating with AIDS |

AIDS with recurrent opportunistic infections or with secondary diseases in multiple body systems; HIV illness with debility and progressive weight loss, with few or no remissions |

|

Sinusitisb |

1-2 incapacitating episodes/yr requiring prolonged (4-6 wks) antibiotics; or > 6 non-incapacitating episodes/yr |

30 |

≥ 3 incapacitating episodes per year requiring prolonged (4-6 wks) antibiotics; or > 6 non-incapacitating episodes/yr |

50 |

Following radical surgery with chronic osteomyelitis; or near-constant symptoms after repeated surgeries |

|

|

|

|

Laryngeal disorders |

Hoarseness, with cord inflammation |

30 |

Hoarseness, with nodules, polyps, or premalignant biopsy changes |

60 |

Constant inability to speak above whisper |

Total laryngectomy; or constant inability to speak |

|

Asthma |

FEV-1 71-80% or FEV-1/FVC 71-80%; or intermittent bronchodilators |

30 |

FEV-1 56-70% or FEV-1/FVC 56-70%; or daily bronchodilators or inhalational anti-inflammatory medication |

60 |

FEV-1 40-55% or FEV-1/FVC 40-55%; or at least monthly physician visits for exacerbations; or ≥ 3/yr courses of corticosteroids |

FEV-1 < 40 %; or FEV-1/FVC <40%; or > 1 attack/wk with episodes of respiratory failure; or requires daily use of high dose corticosteroids or immunosuppressive medications |

|

Allergic rhinitis |

Without polyps but > 50% bilateral or 100% unilateral obstruction |

30 |

With polyps |

|

|

|

|

Congestive heart failure (CHF)c |

Symptoms with 7-10 METs workload; or continuous medication required. |

30 |

Symptoms with 5-7 METs workload; or cardiac enlargement on ECG, echo, or X-ray |

60 |

> 1 episode acute CHF in past year; or symptoms with 3-5 METs workload; or left ventricular ejection fraction of 30-50% |

Chronic CHF; or symptoms with ≤ 3 METs work-oad; orleft ventricular ejection fraction of < 30% |

|

Condition |

10% |

|

20-30% |

|

40-50% |

|

60-70% |

100% |

|

Supraventricular arrhythmias |

Permanent atrial fibrillation; or 1-4 episodes/yr of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or other supra-ventricular tachycardia |

30 |

Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or other supraventricular tachycardia, with > 4 four episodes/yr |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hypertensiond |

Diastolic pressure predominantly 100 or more, or systolic pressure predominantly 160 or more, or requires continuous medication for control |

20 |

Diastolic pressure predominantly 110 or more, or systolic pressure predominantly 200 or more |

40 |

Diastolic pressure predominantly 120 or more |

60 |

Diastolic pressure predominantly 130 or more |

|

|

Varicose veins |

Intermittent edema/symptom relief via elevation or compression hose |

20 |

Chronic edema, incompletely relieved by elevation of legs |

40 |

Chronic edema and stasis changes |

60 |

Chronic edema or stasis change and persistent ulceration |

Massive board-like edema with constant rest pain |

|

Irritable bowel syndrome |

Moderate: frequent episodes of bowel disturbance with abdominal distress |

30 |

Severe: diarrhea, or alternating diarrhea and constipation, with fairly constant abdominal distress |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ulcerative colitis |

Moderate, with infrequent exacerbations |

30 |

Moderately severe, with frequent exacerbations |

|

|

60 |

Severe: numerous attacks a year and malnutrition; health only fair during remissions |

Pronounced: marked malnu-trition, anemia, and debility, or with serious complication as liver abscess |

|

Ulcer, duodenal |

Mild, with recurring symptoms 1-2 times/yr |

20 |

Moderate: recurring episodes of severe symptoms 2-3 times/yr averaging 10 days; orwith continuous moderate manifestations |

40 |

Moderately severe: impaired health manifested by anemia and weight loss; or recurrent incapacitating episodes ≥ 10 days for ≥ 4 times/yr |

60 |

Severe: pain only partially relieved by therapy, periodic vomiting, recurrent hematemesis or melena, with anemia and weight loss producing impaired health |

|

|

Hiatal hernia |

Two or more of the symptoms from the 30% evaluation, but of less severity |

30 |

Recurrent epigastric distress with dysphagia, pyrosis, and regurgitation, accompanied by substernal or arm or shoulder pain; with con-siderable health impairment |

|

|

60 |

Pain, vomiting, weight loss and hematemesis or melena with moderate anemia; or other symptom combinations producing severe health impairment |

|

|

Condition |

10% |

|

20-30% |

|

40-50% |

|

60-70% |

100% |

|

Inguinal hernia |

Postoperative recurrent, readily reducible, and well supported by truss or belt |

30 |

Small, post-operative recurrent, or unoperated irremediable not well supported by truss, or not readily reducible |

|

|

60 |

Large, post-operative, recurrent, or inoperable and not readily supported or reducible |

|

|

Renal dysfunctione |

|

30 |

Constant or recurring albuminuria with casts or red blood cells; or transient/slight edema or hypertension ≥ 10% disabling under diagnostic code 7101 |

|

|

60 |

Constant albuminuria with some edema; or definite decrease in kidney function; or hypertension ≥ 40% disablingunder code 7101 |

Chronic dialysis; or sedentary because of: persistent edema and albuminuria; or BUN > 80; or creatinine > 8; or marked organ dysfunction, especially cardiovascular |

|

Voiding dysfunction |

|

20 |

Requires wearing of absorbent materials which must be changed < 2 times/day |

40 |

Requires wearing of absorbent materials which must be changed 2-4 times/day |

60 |

Requires use of appliance or absorbents which must be changed > 4 times/day |

|

|

Urinary frequency |

Daytime voiding interval 2-3 hr; or nocturia 2 times per night |

20 |

Daytime voiding interval 1-2 hr; or nocturia 3-4 times per night |

40 |

Daytime voiding interval < 1 hr; or nocturia ≥ 5 times per night |

|

|

|

|

Disease, injury or adhesions of female reproductive organs |

Symptoms that require continuous treatment |

30 |

Symptoms not controlled by continuous treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Uterus and ovaries, removal |

|

30 |

Uterus only or both ovaries |

50 |

Uterus and both ovaries |

|

|

|

|

Breast surgerye |

|

30 |

Unilateral breast surgery with significant alterations in size or focus |

40 |

Unilateral modified radical mastectomy |

60 |

Bilateral modified radical mastectomy |

|

|

50 |

Unilateral radical mastectomy; or bilateral breast surgery with significant alterations |

|||||||

|

Anemia |

Hemoglobin ≤ 10 with symptoms like weakness, fatigue, or headaches |

30 |

Hemoglobin ≤ 8 with symptoms like weakness, fatigue, dyspnea, headaches, or lightheadedness |

|

|

70 |

Hemoglobin ≤ 7 with dyspnea on mild exertion, or tachycardia (100-120), or cardiomegaly or syncope (≥ 3 in past 6 months) |

Hemoglobin ≤ 5, with high output CHF or dyspnea at rest |

|

Condition |

10% |

|

20-30% |

40-50% |

|

60-70% |

100% |

|

Dermatitis or eczema |

5-19% of body; or systemic corticosteroid or immunosuppressive drugs required for < 6 wks in past 12 months |

30 |

20-40% of body; or systemic corticosteroid or immunosuppressive drugs required for ≥ 6 wks in past 12 months |

|

60 |

> 40% of body; or constant systemic corticosteroid or immunosuppressive drugs required in past 12 months |

|

|

Urticaria |

Episodes ≥ 4 times in past 12 months; and responding to antihistamines or sympathomimetics |

30 |

Debilitating episodes ≥ 4 times in past 12 months, requiring intermittent systemic immunosuppresive therapy |

|

60 |

Debilitating episodes ≥ 4 times in past 12 months, despite continuous systemic immunosuppresive therapy |

|

|

Acne |

Deep acne < 40% face/neck or elsewhere |

30 |

Deep acne ≥ 40% face/neck |

|

|

|

|

|

Hypothyroidism |

Fatigability, or continuous medication required for control |

30 |

Fatigability, constipation, and mental sluggishness |

|

60 |

Muscular weakness, mental disturbance, and weight gain |

Cold intolerance, muscular weakness, cardiovascular involvement, mental changes (e.g., dementia, depression), bradycardia (< 60 beats/min), and sleepiness |

|

Addison’s disease |

|

20 |

1-2 crises or 2-4 episodes in past 12 months; or weakness and fatigability; or corticosteroids required for control |

40 |

3 crises or ≥ 5 episodes in past 12 months |

60 |

≥ 4 crises in past 12 months |

|

|

Diabetes mellitus |

Manageable by restricted diet only |

20 |

Requiring insulin or oral hypoglycemics and restricted diet |

40 |

Requiring insulin, restricted diet, and regulation of activities |

60 |

Requiring insulin, with ketoacidosis or hypoglycemia requiring ≥ 1-2 hospitalizations /yr or twice-a-month clinic visits, plus complications that would be not be compensable if separately rated |

Requiring > 1 daily injection of insulin, with ketoacidosis or hypoglycemia requiring ≥ 3 hospitalizations/yror weekly clinic visits, plus either progressive loss of weight/strength or complications that would be compensable if separately rated |

|

Migraine |

Prostrating attacks on average of one in 2 months over last several months |

30 |

Prostrating attacks on average of once a month over last several months |

50 |

Very frequentcompletely prostrating and prolonged attacks, with economic inadaptablity |

|

|

|

|

Condition |

10% |

|

20-30% |

|

40-50% |

|

60-70% |

100% |

|

Epileptic seizurese |

Confirmed diagnosis of epilepsy |

20 |

≥ 1 major seizurein last 2 years; or ≥ 2 minor seizures in past 6 months |

40 |

≥ 1 majorseizure in last 6 months or 2 in past year; or averaging 5-10 minor seizures per week |

60 |

Averaging ≥ 1 major seizure in 4 months in past year; or 9-10 minor seizures per wk |

Averaging ≥ 1 major seizure per month in past year |

|

aOSI = occupational and social impairment. ADL = activities of daily living. bIncapacitating means requiring bed rest prescribed by a physician and treatment by a physician. cThese rules are also used as a major determinant of disability for other cardiac diseases, such as coronary artery disease (post MI or post CABG), valvular heart disease, hypertensive heart disease, etc. dHypertension or isolated systolic hypertension must be confirmed by readings taken 2 times on at least three different days. eThere is also an 80 percent disability level for these conditions, defined as follows: • renal dysfunction that is characterized by persistent edema and albuminuria with BUN 40-80; or creatinine 4-8; or poor health with lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, or limitation of exertion (renal dysfunction). • bilateral radical mastectomy (breast surgery). • averaging ≥ 1 major seizure in 3 mo in past year; or > 10 minor seizures per week (epileptic seizures). SOURCE: Summarized from 38 CFR §4 Subpart B. |

||||||||

the committee did not identify a strong evidence basis for assigning any percentages to any particular disorder. Second, because each disorder has a unique set of symptoms, complications, objective findings, prognostic features, and treatment options and efficacy, there may be little or no common basis on which to make a comparison among disorders. Third, it is apparent that the ratings for each category of disease were derived by the specialists responsible for that disease (endocrinologists for diabetes and hypothyroidism, neurologists for epilepsy and migraine, gastroenterologists for irritable bowel and ulcerative colitis, and so forth). Not only may different specialists view their particular sets of diseases differently, it is not clear that any cross-communication took place among different specialists in an effort to calibrate percentage ratings across diseases.

Notably, there are some “intra-specialty” ratings where two diseases affecting a similar organ have seemingly divergent criteria for the same percentage rating. For example, allergic rhinitis is rated at 30 percent simply if polyps are present—which are not only often minimally symptomatic but are also readily treatable. In contrast, sinusitis achieves a rating of 30 percent only if there are three or more incapacitating episodes per year requiring prolonged (4-6 weeks) use of antibiotics or else at least six non-incapacitating episodes per year.

Furthermore, there are seemingly similar conditions that have widely disparate ratings. Evidence suggests that chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and fibromyalgia share much in common with one another and with other functional somatic syndromes (Aaron and Buchwald, 2001; Gardner et al., 2003). However, while CFS can be rated as high as 100 percent, the maximal rating for fibromyalgia is 40 percent even when symptoms are “constant and refractory to therapy.”

Two important rating thresholds for a disorder are 40 and 60 percent. This is because total disability may be assigned, when the rating according to the schedule is less than 100 percent,

when the disabled person is … unable to secure or follow a substantially gainful occupation as a result of service-connected disabilities: Provided That, if there is only one such disability, this disability shall be ratable at 60 percent or more, and that, if there are two or more disabilities, there shall be at least one disability ratable at 40 percent or more, and sufficient additional disability to bring the combined rating to 70 percent or more (38 CFR §4.16; emphasis and capitalization in original).

According to 38 CFR §4.1, “the percentage ratings represent as far as can practicably be determined the average impairment in earning capacity resulting from such diseases and injuries and their residual conditions in civil occupations.” Thus, the overriding consideration in setting the VASRD ratings does not seem to be providing compensation for pain and suffering

or offering a lower threshold for paying disability to individuals who have risked their lives as public servants. Instead, the VASRD ratings are more akin to factors influencing civilian worker compensation.

Conditions with No or Minimal Disability

Partly because the primary explicit factor in VASRD ratings is the effect on earnings capacity, the presence of a disorder itself—even if it is service-connected—may result in no (0 percent) or minimal (10 percent) disability ratings. Features that may result in a condition being rated as 0 percent disability (Table 5-3) include it being asymptomatic (for example, sinus disease detected only by radiographic imaging, mild anemia, or asymptomatic HIV disease), very mild (vitiligo in body areas normally covered by clothing, superficial acne, small patches of eczema, small reducible hernias), or infrequent (occasional irritable bowel symptoms, migraine headaches less than once a month). Features that result in ratings at the minimum of 10 percent (Table 5-4 as well as Table 5-2) include mildly deforming conditions (vitiligo in exposed body parts, partial loss of the auricle of the ear) or functional deficits, such as complete loss of smell or taste, that do not impair the ability to work in most occupations. Other features leading to low levels of disability include symptoms being mild and episodic, the disease being minimal according to laboratory parameters, and the ability to control the disease well with simple treatments.

Factors that Influence Disability Ratings

While the overarching consideration in VASRD ratings is a disorder’s effect on earnings capacity, Table 5-5 summarizes a number of secondary factors that also influence percentage ratings. These include symptom severity and frequency; objective, independently verifiable findings on physical examination or diagnostic testing; deformities; permanence (that is, not likely to improve over time); functional impairment (occupational and, secondarily, social); treatment intensity and responsiveness; extent of outpatient or inpatient health use required for the condition; features of the condition that adversely affect the long-term prognosis; and disease complications.

Symptom-Based Disorders (Including Pain)

Some disorders are characterized exclusively by patient-reported symptoms and lack objective findings on physical examination, laboratory testing, radiographic imaging, or other diagnostic tests. These include conditions such as CFS, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, migraine, most

TABLE 5-3 Examples of Disorders with a No (0%) Disability Rating Level

|

Code[s] |

Disorder |

Severity level |

|

9200s–9400s |

Mental disorders |

Symptoms neither cause occupational and social impairment nor require continuous medication |

|

6510 |

Sinusitis |

Detected by X-ray only |

|

6315 |

HIV-related illness |

Asymptomatic, with or without lymphadenopathy or low T4 count |

|

7319 |

Irritable bowel syndrome |

Mild disturbances of bowel function; occasional abdominal distress |

|

7338 |

Hernia, inguinal |

Not operated but remediable; or small, reducible, no true protrusion |

|

7500s |

Renal dysfunction |

Albuminuria and casts with history of acute nephritis |

|

7610–7615 |

Diseases of female reproductive organs |

Symptoms that do not require continuous treatment |

|

7619 |

Ovary |

Removal of one ovary with or without partial removal of the other |

|

7626 |

Breast surgery |

Wide local excision, without significant alteration of size or focus |

|

7700 |

Anemia |

Hemoglobin < 10 gm/100 ml, but asymptomatic |

|

7806 |

Dermatitis or eczema |

< 5% of body and only topical therapy required during past year |

|

7823 |

Vitiligo |

With no exposed areas affected |

|

7828 |

Acne |

Only superficial (comedones, papules, pustules), not deep acne |

|

8100 |

Migraine |

Attacks less than once in two months in last several months. |

|

SOURCE: 38 CFR §4 Subpart B. |

||

TABLE 5-4 Examples of Disorders (excluding those in Table 5-2) with a Minor (10%) Disability Rating Level

|

Code |

Disorder |

Severity level |

|

6210 |

Chronic otitis externa |

Swelling, dry and scaly or serous discharge, and itching, requiring frequent and prolonged treatment |

|

6275 |

Sense of smell |

Complete loss |

|

6276 |

Sense of taste |

Complete loss |

|

7823 |

Vitiligo |

With exposed areas affected |

|

SOURCE: 38 CFR §4 Subpart B. |

||

TABLE 5-5 Factors that Influence VASRD Percentage Disability Ratings

|

Factor |

Example Conditions |

|

Primary |

|

|

Average impairment in earning capacity expected in civil occupations |

All conditions |

|

Secondary |

|

|

Severity and frequency of symptoms (e.g., number of exacerbations, number of weeks or months, “incapacitating” episodes) |

Seizures Migraine Fibromyalgia Arthritis Back conditions |

|

Objective findings (e.g., on physical examination, laboratory tests, X-rays) |

Dizziness (vestibular findings) |

|

Deformity (e.g., loss or mutilation of body part) |

Amputations Surgical resection Acne (deep, worse than superficial) |

|

Permanence (clear evidence that “time will not heal”) |

HIV disease (progression to AIDS) |

|

Functional impairment (especially work; secondarily social) |

Chronic fatigue syndrome CHF Laryngeal (level of speech impairment) |

|

Treatment response (e.g., refractory to medications, failed surgery) |

Sinusitis Inguinal hernia Fibromyalgia |

|

Treatment intensity (e.g., continuous, more complicated or toxic therapies) |

Diabetes (insulin) Asthma (steroids) Renal function (dialysis) Urinary voiding (frequency, number of diapers) |

|

Health care use (e.g., number of hospitalizations or clinic visits) |

Diabetes (frequency of clinic visits) |

|

Severity of condition which may affect future prognosis |

Hypertension (level of blood pressure) Renal function (level of creatinine) |

|

Complications of condition |

Duodenal ulcer (anemia, weight loss) Ulcerative colitis (abscess) Hypothyroidism (mental, cardiac) |

cases of low back pain, and mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Table 5-2 offers a number of examples of how disability ratings are assigned for these disorders. One of the most prevalent physical symptoms in disorders of this sort is pain, which is a cardinal symptom in musculoskeletal disorders. It is informative to examine how the VASRD rating system deals with an entirely self-reported symptom like pain.

Pain can be considered in rating the disability associated with musculoskeletal disorders if the pain is associated with “functional loss” and “supported by adequate pathology and evidenced by the visible behavior of the claimant undertaking the motion.” (38 CFR §4.40). This would suggest that objective findings are to be sought by the examiner before using pain alone as a basis for disability. However, this paragraph in 38 CFR goes on to say that “a part which becomes painful on use must be regarded as seriously disabled.” Painful motion is further elaborated upon in 38 CFR §4.59, which states, “With any form of arthritis, painful motion is an important factor of disability; the facial expression, wincing, etc., on pressure or manipulation, should be carefully noted and definitely related to affected joints.” The examiner is also encouraged to identify the presence of more objective findings such as muscle spasm, crepitus, joint instability, malalignment, or other evidence of articular or periarticular pathology. Taken together, these paragraphs imply some leeway for the examiner to incorporate pain and its functional consequences in assessing musculoskeletal disorder disability. Nonetheless, the context of both paragraphs seems to caution raters against using pain as the sole or even predominant determinant in the absence of concomitant objective findings.

Disorders with a Relapsing/Remitting Course

Certain disorders listed in the VASRD exhibit a relapsing and remitting course, that is, there are some periods of time when symptoms are manifest or exacerbated and others when they are latent or subclinical. Among the conditions with these characteristics are multiple sclerosis (MS), lupus, and many mental disorders, including PTSD and depression. These disorders present a challenge for raters: It can be difficult to assign a level of disability to them because the absence of disabling symptoms does not mean that the subject is free from the effects of the disorder. As Table 5-2 illustrates, the statutory criteria for remitting/relapsing conditions do not use a consistent approach to managing this issue, varying in how the frequency and effect of symptoms are factored, whether response to treatment is considered, and whether nonoccupational impacts are addressed.

The VASRD listing for MS does not specify particular symptoms or levels of symptom severity and corresponding ratings. Instead, the regulation simply states that disability be rated “in proportion to the impairment” (38 CFR §4.124a). A minimum rating of 30 percent is assigned to claimants with a diagnosis of MS.

As noted above, PTSD is managed differently than other conditions in that it is governed by the general mental-disorders ratings schedule rather than by a PTSD-specific set of criteria.

Comparing VASRD Ratings for Mental and Physical Disorders

Table 5-2 allows one to compare how ratings of mental disorders (the first entry in the table) compare to physical disorders (the rest of the entries in the table). Several overall observations can be made:

-

There is one general rating scheme that is applied to all types of mental disorders, which makes it necessary to lump together a very heterogeneous set of symptoms and signs from multiple conditions into a single spectrum of problems. Furthermore, the rating scheme particularly focuses on symptoms from schizophrenia, mood, and anxiety disorders. Although there are other examples of groups of disorders that are handled with one general rating scheme—disorders of the spine, disorders of the female reproductive system, renal disease, and certain other physical conditions—this “lumping” is carried to an extreme in the case of mental disorders, allowing very little differentiation across specific conditions.

-

Some of the secondary factors shown in Table 5-6 (objective findings, deformity, physical complications) that may influence percentage ratings cannot be met for mental disorders. This could theoretically put mental disorders at a relative disadvantage compared to physical disorders in terms of achieving higher percentage ratings.

-

Two important threshold levels for increases in disability benefits—40 and 60 percent—cannot be assigned to mental disorders. However, there are also a number of physical disorders that do not have the 40 and 60 percent options, and raters always have the option of using 50 and 70 percent ratings for mental disorders, which may serve to mitigate what would otherwise be a major disadvantage.

-

Occupational and social impairment (OSI) is the central factor used in determining each level of disability for mental disorders. However, little guidance is given about how to measure either OSI or its differential impairment across different percentage ratings. Furthermore, the various secondary factors that are used in rating physical disorders (Table 5-6) are not applied to mental disorder ratings, which gives the primary factor—OSI—a value in determining the ratings that is disproportionately high compared to other symptoms.

Summary Observations

PTSD and other conditions that are patient-reported or have relapsing and remitting symptoms present a challenge for raters. The rating criteria for such conditions use an inconsistent approach, which varies in how the frequency and effect of symptoms are factored, whether response to treatment is considered, and whether nonoccupational effects are addressed.

TABLE 5-6 Numbers of Veterans Receiving Disability Compensation on September 30, 1999–2006, by Selected Diagnostic Categories, Primary Rated Service-Connected Disability Only*

|

Condition (Diagnostic Category/ies) |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

% Increase 1999–2006 |

% of Total 2006 |

|

Other mood disorders (9431–9433, 9435) |

4,376 |

5,874 |

7,052 |

8,698 |

10,706 |

12,344 |

14,222 |

15,946 |

264.4% |

0.6% |

|

Psychotic disorders (9201–9211) |

90,334 |

87,209 |

84,344 |

81,657 |

79,210 |

76,804 |

74,387 |

72,064 |

−20.2% |

2.6% |

|

All anxiety disorders |

194,671 |

199,660 |

204,340 |

216,326 |

235,168 |

251,195 |

269,825 |

286,625 |

47.2% |

10.5% |

|

—PTSD (9411) |

98,839 |

109,598 |

119,685 |

137,113 |

160,537 |

181,000 |

203,377 |

223,099 |

125.7% |

8.2% |

|

—Other anxiety disorders (9400–9410, 9412–9413) |

95,832 |

90,062 |

84,655 |

79,213 |

74,631 |

70,195 |

66,448 |

63,526 |

−33.7% |

2.3% |

|

Fibromyalgia (5025) |

796 |

1,013 |

1,235 |

1,521 |

1,887 |

2,156 |

2,493 |

2,766 |

247.5% |

0.1% |

|

Colitis (7323) |

6,255 |

6,299 |

6,312 |

6,440 |

6,501 |

6,612 |

6,691 |

6,783 |

8.4% |

0.2% |

|

Irritable bowel syndrome (7319) |

3,406 |

3,515 |

3,622 |

3,787 |

3,987 |

4,189 |

4,359 |

4,607 |

35.3% |

0.2% |

|

Major depression (9434) |

4,570 |

6,458 |

8,173 |

10,609 |

14,212 |

17,848 |

22,024 |

26,226 |

473.9% |

1.0% |

|

All other mental disorders (9300–9327, 9416–9425, 9440, 9520, 9521) |

13,775 |

13,819 |

13,887 |

14,035 |

14,366 |

14,645 |

15,093 |

15,591 |

13.2% |

0.6% |

Moreover, the absence of disabling symptoms does not mean that the subject is free from the effects of the disorder. PTSD is managed differently than almost all other conditions in that it is subject to the general mental disorders ratings schedule, which is not focused on its particular symptomatology, rather than being subject to a set of criteria that is specific to the disorder.

Trends in Disability Compensation

Numbers of Veterans Receiving Disability Compensation

In response to a request, VA provided the committee with data regarding the numbers of veterans receiving disability benefits for the years 1999– 2006. Table 5-6 categorizes these data by the primary rated disability that is either the condition rated as most disabling or equal to the highest rated condition. Table 5-7 lists the same conditions but reports the total number of veterans who have each disability, whether or not it is their primary rated disability. Note that a veteran may be counted more than once in Table 5-7 because he or she may be rated for multiple listed conditions.

The bottom row of Table 5-6 shows that the total number of veterans receiving disability benefits increased by approximately 18.8 percent over the seven years shown. The rate of increase varied widely by disability category, however. The primary disability diagnosis categories with the largest percentage increase over that seven-year period were major depression (474 percent increase), diabetes (388 percent), other mood disorders (264 percent), and fibromyalgia (247 percent). PTSD showed the next largest percentage increase—126 percent—which is particularly noteworthy because more veterans had PTSD as their primary disability than any of the other conditions.

The trend for PTSD in comparison with other mental disorders is of interest. The number of beneficiaries whose primary disability was “other anxiety disorders” actually declined by 34 percent at the same time that the PTSD numbers were rising sharply. The only other mental disorder category for which a decline occurred was psychotic disorders. By contrast, the numbers for affective disorders—major depression and other mood disorders— and for all other mental disorders increased. It is thus possible that some of the growth in PTSD was actually a change in diagnostic labeling with, for example, fewer veterans being classified with other anxiety disorders than in the past because these veterans were now being diagnosed with PTSD. It is of note that the percentage increase in the number of beneficiaries for all anxiety disorders was approximately 47 percent.

The changes in the numbers in Table 5-7—that is, the changes in the totals of all veterans with a particular disability, whether it was their pri-

TABLE 5-7 Numbers of Veterans Receiving Disability Compensation on September 30, 1999–2006, by Selected Diagnostic Categories, Any Rated Service-Connected Disability

|

Condition (Diagnostic Category/ies) |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

% Increase 1999–2006 |

% of Total 2006 |

|

Other mood disorders (9431–9433, 9435) |

6,799 |

8,981 |

10,681 |

13,299 |

16,352 |

18,893 |

21,837 |

24,624 |

262.2% |

0.9% |

|

Psychotic disorders (9201–9211) |

93,646 |

90,397 |

87,425 |

84,648 |

82,101 |

79,616 |

77,117 |

74,755 |

−20.2% |

2.7% |

|

All anxiety disorders |

257,156 |

261,113 |

265,218 |

279,406 |

301,607 |

320,304 |

343,098 |

364,445 |

41.7% |

13.4% |

|

—PTSD (9411) |

122,034 |

133,745 |

144,920 |

165,898 |

193,791 |

217,855 |

244,846 |

269,331 |

120.7% |

9.9% |

|

—Other anxiety disorders (9400–9410, 9412–9413) |

135,122 |

127,368 |

120,298 |

113,508 |

107,816 |

102,449 |

98,252 |

95,114 |

–29.6% |

3.5% |

|

Fibromyalgia (5025) |

1,561 |

2,059 |

2,548 |

3,218 |

4,070 |

4,810 |

5,630 |

6,351 |

306.9% |

0.2% |

|

Colitis (7323) |

7,843 |

7,953 |

8,031 |

8,273 |

8,515 |

8,746 |

8,963 |

9,205 |

17.4% |

0.3% |

|

Irritable bowel syndrome (7319) |

11,809 |

12,612 |

13,453 |

14,647 |

15,979 |

17,206 |

18,555 |

19,908 |

68.6% |

0.7% |

|

Major depression (9434) |

7,533 |

10,697 |

13,731 |

18,225 |

24,350 |

30,593 |

37,810 |

45,235 |

500.5% |

1.7% |

|

All other mental disorders (9300–9327, 9416-9425, 9440, 9520, 9521) |

23,243 |

23,631 |

23,996 |

24,851 |

25,965 |

27,028 |

28,490 |

30,087 |

29.4% |

1.1% |

|

Multiple sclerosis (8018) |

7,564 |

7,598 |

7,532 |

7,565 |

7,630 |

7,699 |

7,674 |

7,717 |

2.0% |

0.3% |

|

Lumbosacral or cervical strain (5237, 5295) |

163,123 |

168,797 |

173,840 |

180,893 |

188,918 |

199,306 |

218,474 |

239,463 |

46.8% |

8.8% |

|

Diabetes (7913) |

36,789 |

36,796 |

44,845 |

105,895 |

149,684 |

176,322 |

201,962 |

226,896 |

516.7% |

8.3% |

|

Asthma (6602) |

42,545 |

44,070 |

45,523 |

47,696 |

50,014 |

52,355 |

55,419 |

58,593 |

37.7% |

2.1% |

|

SOURCE: Data provided to the committee by VA. |

||||||||||

mary rated disability or not—are generally quite similar to the changes in Table 5-6. The percentage increase for PTSD was similar to the percentage increase in all anxiety disorders, which suggests that the number of veterans with a secondary diagnosis of anxiety disorder or PTSD has grown at about the same rate as the number of veterans with a primary diagnosis for those disorders. In contrast, for most of categories listed (fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, major depression, all other mental disorders, multiple sclerosis, lumbarsacral or cervical strain, diabetes, and asthma), the number of all veterans with a particular disorder has increased at a faster rate than the number of veterans with that disorder as their primary disability.

The information in these tables is consistent with the suggestion that the growth in PTSD awards is due to a greater willingness on the part of veterans to apply for PTSD compensation. It may also, though, reflect in part an increasing tendency for VA to recognize a diagnosis of PTSD and, more generally, to recognize disability resulting from any mental disorder. Unlike most other categories, PTSD as a secondary diagnosis has not increased more rapidly than the number of primary PTSD diagnoses.

Demographic Characteristics of Beneficiaries

Table 5-8 illustrates two well-known trends: an increasing percentage of females in the beneficiary population, and a decrease in the average age in the beneficiary population. These trends presumably reflect trends in the general population of veterans. There are several distinctive features that can be discerned in the characteristics and trends for PTSD beneficiaries. First, the percentage of males among PTSD beneficiaries is slightly higher than the percentage of males among all beneficiaries, and it declined by a very small amount between 1999 and 2006. Second, the age of PTSD beneficiaries has also declined by a very small amount (especially for PTSD as a primary disability14). In short, while the major demographic trends affecting most beneficiaries are also visible among PTSD beneficiaries, they are less pronounced.

Trends in Combined Ratings, Future Exams, and IU Designations

Table 5-9 describes changes between 1999 and 2006, by diagnostic category, in the mean combined rating of a disorder, in the percentages of beneficiaries classified as IU, and in the percentage of beneficiaries for whom a future exam is scheduled. The data on combined ratings show that the ratings had a modest upward trend in almost all diagnostic categories

TABLE 5-8 Demographic Characteristics of Beneficiaries on September 30, 1999, and September 30, 2006

TABLE 5-9 Trends in Combined Ratings, Future Exams, and IU Designations of Beneficiaries on September 30, 1999, and September 30, 2006

and that the mean rating for PTSD is and has been relatively high compared to most other diagnostic categories.

The percentage of beneficiaries classified as IU nearly doubled between 1999 and 2006. Corresponding changes in this percentage for PTSD and for other mental disorders were generally similar. The absolute magnitude of the percentage changes, however, were generally larger for mental disorders, including PTSD, because these percentages were already somewhat higher in 1999 than the IU percentages for other diagnostic categories. For PTSD in particular, almost 30 percent of beneficiaries with a PTSD primary diagnosis were classified as IU in 2006, and more than one-third of all beneficiaries with an IU classification had either a primary or secondary diagnosis of PTSD.

The explanations for the high rate of IU among PTSD beneficiaries, as well as for the large differential between mental disorders in general and other diagnostic categories, may be important. One possible explanation is that the ratings for mental disorders incorporate information on occupational functioning (e.g., in the GAF), and the use of this information in the ratings process may provide a stronger basis for the IU classification than occurs with disorders for which information on occupational funding is not incorporated. A second possibility is that it is more difficult to get access to psychiatric care than it is to get access to care for somatic disorders, so those with psychiatric disorders would have a stronger incentive to seek increased access based on an IU classification. A third possible explanation is that the rigidity in the current rating schedule for PTSD, which focuses on occupational impairment, may lead rating technicians to use IU as a means to account for individualized circumstances that can otherwise not be accounted for under the schedule.

The practice of beneficiaries scheduling future exams became relatively less frequent over the 1999–2006 period, and the total number of beneficiaries scheduled for such exams rose almost imperceptibly from 1999 to 2006 (from 57,938 to 58,879; data not shown in Table 5-9). In 1999, the percentage of beneficiaries who scheduled future exams varied widely among the various diagnostic categories, but such scheduling was clearly most frequent for those with depression and other mood disorders, PTSD, and fibromyalgia. Veterans with mental disorders as their primary diagnoses accounted for 37 percent of all future exams scheduled in 1999, and those with mental disorders as a primary or secondary diagnosis accounted for 48 percent of all future exams. By 2006, while the future exams continued to be concentrated among beneficiaries with primary or secondary mental disorders, the percentage of beneficiaries who scheduled these exams dropped sharply. For PTSD primary beneficiaries, the decline was from 14.2 to 5.6 percent. The reasons for the decline in rates of future exams is unclear, but it appears at this point that if those reasons are making veterans less likely

to seek care for PTSD—as some have suggested—the overall magnitude of this effect must be quite small.

Availability of PTSD Disability Compensation Data

Tables 5-6 through 5-9 summarize some basic data on the characteristics of PTSD beneficiaries and the details of their compensation over time. However, other information that would have helped inform the committee’s evaluations were not available. The committee has the following recommendations for addressing gaps they identified:

-

Data fields recording the application and reevaluation of benefits should be preserved over time, rather than being overwritten when final determinations are made, so that better analyses of the PTSD disability application and review process can be performed.

-

Data should be gathered and coded at two points in the process where there is currently little information available: before claims are made, and after compensation decisions are rendered.

Data such as these will facilitate more informed future analyses of PTSD disability compensation issues.

Other Disability Rating Systems for Mental Disorders

The committee was asked to address other methods of evaluating disability from mental impairments. The approaches taken in the American Medical Association (AMA) Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment (2001), the “Psychological Impairment” chapter of AMA’s Disability Evaluation (Eliashof and Streltzer, 2003), and the Social Security Administration’s (SSA’s) Blue Book (2005) are summarized.

AMA Guides to Assessment of Permanent Impairment

Following the lead of the American Psychiatric Association, the AMA expresses skepticism about assigning percentage ratings to the level of impairment from mental disorders:

Unlike cases with some organ systems, there are no precise measures of impairment in mental disorders. The use of percentages implies a certainty that does not exist. Percentages are likely to be used inflexibly by adjudicators, who then are less likely to take into account the many factors that influence mental and behavioral impairment. In addition, the authors are unaware of data that show the reliability of the impairment percentages. After considering this difficult matter, the Committee on Disability and

Rehabilitation of the American Psychiatric Association advised Guides contributors against the use of percentages in the chapter on mental and behavioral disorders of the fourth edition, and that remains the opinion of the authors of the present chapter (AMA, 2001, §14.3).

The AMA publication offers guidance on several aspects of assessing mental disorders, including the variability of function over time, information sources, claimant motivation, persistence of functional impairment, the dimensions of a functional assessment, determination of social functioning, and the role of treatment response. This guidance is briefly summarized below.

Impairment related to mental disorders can fluctuate considerably over time. Thus, as noted in §14.1a, “it is important to obtain evidence over a sufficiently long period of time…. This evidence should include treatment notes, hospital discharge summaries, work evaluations, and rehabilitation progress notes if they are available.” Multiple sources of information (both medical and nonmedical) may be used to make a determination about the individual’s daily living, social functioning, concentration, persistence, pace, and ability to tolerate increased mental demands, such as stress (AMA, 2001).

The AMA Guides notes that lack of motivation on the part of the person claiming disability is difficult to assess since it may be due to a number of factors, including: the mental illness itself, e.g., depression or schizophrenia; fear of losing entitlements or other benefits of being ill; a side effect of some psychotropic medications; conscious malingering; the natural demoralization that can be associated with any chronic illness; and inadequate social network support. Thus, as stated in §14.2b, “the determination of motivation is often nonempirical, and conclusions are all too often drawn on the basis of prejudice. Many times, an individual’s motivation is not well understood even after careful assessment.”

The determination of the persistence of functional impairment is inevitably accompanied by some degree of uncertainty. The Guides indicates that it is important to acknowledge the tension that exists between labeling the disability as permanent, which can make improvement less likely, and being overoptimistic about recovery, since mental disorders are often chronic or relapsing. As stated in §14.2c, “The use of the impairment label can be seen as pessimistic, providing an adverse prediction that may be self-fulfilling. However, the tendency for physicians and others to minimize psychiatric impairments must also be considered; this … may lead to failure to refer individuals for potentially helpful rehabilitative measures.”

Section 14.3 outlines a multidimensional functional assessment comprising four main categories: (a) activities of daily living; (b) social functioning; (c) concentration, persistence, and pace; and (d) work functioning.

The section indicates that independence and sustainability of activities should also be considered and that the evaluating clinician should ascertain whether limitations in activities are due to the mental disorder or to other factors, such as lack of money or transportation. It notes that social functioning may be more difficult to assess than occupational functioning, since the latter can be gauged by employment history, absenteeism, and other outcomes that are more easily measured. Advice is provided in §14.3b: