Panel IV

Building U.S.–Indian Research and Development Cooperation

Moderator:

Mary Good

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Dr. Good observed that the members of the fourth panel, drawn from the top echelons of research and development (R&D), were in an excellent position to articulate how U.S.–Indian cooperation in R&D could be further strengthened. She then turned to introduce the first speaker, Dr. Swati Piramal, the director of Strategic Alliances and Communications of Nicholas Piramal Indian Limited (NPIL), a major Indian pharmaceutical firm. Dr. Good also noted that Dr. Piramal had been named to the Indian prime minister’s board of advisers, and thus had a perspective on discussions of these issues taking place at the highest level in India.

Swati Piramal

Nicholas Piramal India Ltd.

Dr. Piramal said that her talk, titled “Partnerships That Prosper,” would present a model for transformation and explain why partnering with Indian companies was good strategy. A few case studies would illustrate the challenges and opportunities arising from the renaissance of science under way in India.

In the quest for the force that reshapes the world, she said, there is always a battlefield; the term she used to refer to it, Kurukshetra, signified a battle without which there is no progress. This battlefield was to be found along a pathway

or journey to the elixir, which constituted a gift that, in India’s case, was the country’s science renaissance.

A Transformative Model: “Leadership in Action”

To illustrate, Dr. Piramal laid out a model for “Leadership in Action”: After stage 1, a Call to Adventure, one would Cross the Threshold in stage 2 to arrive at a supreme ordeal on the battlefield, the Kurukshetra of which she had spoken. The Hero’s Journey, stage 3, leads to stage 4, The Elixir or Gift. The fundamental transformation depicted by this model would be the object of her focus.

Stage 1:

Prepare to Journey

This was synonymous with the Call to Adventure. It is important here to see the world as full of possibilities, to shift one’s view of the world from one of resignation to one of possibility. The speakers of that morning who had pointed to the many things wrong with India might have been correct to do so, but one needs to leave behind the conviction that these things could not change for the belief that they could.

Stage 2:

Cross the Threshold

How is this step to be taken? Julius Caesar decided on the 11th of January in 49 B.C. to lead his army across the river separating Gaul, of which he was governor, from the Roman heartland and to undertake a civil war against Pompey, then ruling in Rome. Approaching the Rubicon, Caesar declared: “Once we pass over this little bridge, there will be no business but by the force of arms and dint of sword.” Sounding the trumpet, he continued: “Let us march on and go wherever the tokens of the gods and the provocations of our enemies call us.” Then he uttered a third and, Dr. Piramal signaled, “very important” sentence: “The die is cast.”

Stage 3:

The Hero’s Journey

“All of us, whether or not we are warriors in the Roman Empire, have this cubic centimeter of chance that pops out in front of our eyes from time to time,” she stated. “The difference between an average person and a warrior is that the warrior is aware of this,” its being one of the latter’s tasks to remain alert to the moment and to act swiftly and powerfully when it arrives.

Stage 4:

The Gift

This is the warrior’s reward.

“You are what your deep, driving desire is.

As your desire is, so is your will.

As your will is, so is your deed.

As your deed is, so is your destiny,”

said Dr. Primal, quoting from the Upanishads. Features of the new reality include the globalization of markets and the intensification of competition that accompanies it and the search for capabilities as technology blurs national boundaries and redefines the value of resources. For India, she added, this new reality includes its own rapidly expanding capability.

President Kalam, an aeronautical engineer, had once urged on India’s scientists with the help of this metaphor: “The bumble bee, according to aeronautical design—or models, or mathematics—cannot fly,” he said. “But fly it does.”

Turning to her own field, Dr. Piramal cited a Cambridge Healthtech report on Globalization of Drug Development published in June 2006 that, surveying 235 executives in the pharmaceutical industry, found that three-quarters of their firms were engaged in drug development in India. Leaving behind its days as a destination for clinical trials, “low IP sensitive discovery outsourcing,” and custom synthesis, India now offers high-value services and partnering opportunities. The skill gap is contracting quickly, and technology is helping India leapfrog its competition and create strategic alliances and other linkages based on either equity or core capabilities. The report held that India currently presents a greater opportunity for improving Western R&D productivity than did China.

Partnerships: Many Objectives, Multiple Models

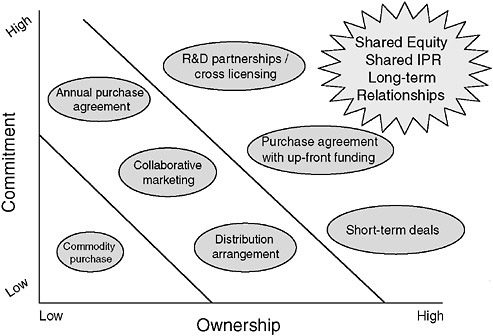

Partnership objectives are many: risk sharing, economies of scale, market-segment access, technology access, and, as Minister Sibal had noted earlier, geographic access. There are multiple partnership models as well; Dr. Piramal posted a chart on which possibilities were arranged in function of the partners’ degrees of commitment and ownership (see Figure 5). She stressed that the only true partnership was a “win-win partnership” in which all parties share both risk and reward equally.

Illustrating the Benefits of Partnerships

Dr. Piramal then offered as an illustration her own company, NPIL, a “practitioner of Indo–U.S. cooperation” that on the strength of partnerships with many American firms had risen from its 1988 ranking of forty-eighth in the formulations area of India’s pharmaceutical sector to fourth in 2005. NPIL’s pursuit of growth through strategic acquisitions, alliances, and joint ventures had brought it into partnership with many foreign firms, among them Allergan, Aventis, and

FIGURE 5 Partnership Models.

Roche. NPIL had put into practice its stated mission—“making a difference to the quality of life by reducing the burden of disease”—on the Indian subcontinent, adding value across the drug-discovery and development processes, whether via R&D, contract manufacturing, or clinical research.

Meanwhile, it had acquired a global footprint by extending its reach into the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and parts of China. Passing through U.S. Customs that very morning, Dr. Piramal told the agent she had come to look after the affairs of her company and added that it employed around 1,000 Americans, who made glass vials at three manufacturing facilities. Remarking that the company’s research scientists were of 22 nationalities, she said: “This is not only about a reverse brain drain, it is not only about outsourcing, it is really about acquisition of global talent.”

Just the day before, NPIL had signed an agreement to acquire from Pfizer a 450-employee facility at Morpeth in the United Kingdom in a transaction carrying a supply agreement that was good through October 2011 and could potentially yield upward of $350 million in revenues. This, Dr. Piramal said, amounts to changing the game: Involved were patented products, not low-value generics, and the company would be supplying them to over 100 countries. Since entering the custom-synthesis market in 2003, NPIL had already taken its place among the world’s top 10 companies, having described “a trajectory of change from nothing

to becoming a global powerhouse of talent, particularly in the areas of chemistry and custom synthesis.”

Scientific “Horsepower” at Lower Cost

In 2005 the company had opened an R&D facility, and Robert Armstrong of Eli Lilly, the next speaker, had recently brought a team of more than 30 to visit it and discuss partnering. Even if NPIL spends what some considered too little on research, Dr. Piramal said, it is able to buy “a lot of scientific horsepower” for its money and so far in 2006 had filed 14 New Chemical Entity (NCE) patents, granted on compounds that are entirely new rather than variants of previous patents. Of these, one was already in clinical trials and three others were about to enter that phase.

NPIL had become the first of India’s private firms to participate in an expedition to Antarctica as part of an effort to mine both Antarctic and oceanic microbial diversity for biotechnological applications.

The company’s pipeline is rich, and its dream is to develop a new drug for $50 million with the potential to go global—an effort that, she said, could cost up to $1 billion in the United States. Even if her cost estimate proves to be off by 100 percent, she said, the gap between $100 million and $1 billion is still significant.

President Clinton had visited NPIL in 2000, and one of the things Dr. Piramal told him was that India lacked good patent attorneys and patent examiners. Since then, India’s backlog of patents has shrunk from 22,000 to 6,000, the result of efforts by both the government and private sector to stimulate change.

Best Practices for Building Partnerships

She then offered a rundown of best practices for building partnerships:

-

anticipating business risk, which includes making a good business plan internally and fostering openness so that it can be refined through interaction;

-

understanding rights and obligations, under which she placed reducing complexity, “playing for the long run,” and eschewing short cuts;

-

preparing realistic feasibility studies rather than overpromising and paying for it later, an important point for Indians, who “always like to promise a lot”;

-

defining expectations clearly;

-

rewarding performance;

-

finding the best talent; and

-

creating planning to bridge management styles.

Elaborating on the last point, Dr. Piramal noted that U.S. firms evince a greater desire for order than did their Indian partners. Because of India’s chaotic

infrastructure, people there rely on “a very quick way of thinking” to achieve “excellence in chaos.” She quoted the famed Sam Pitroda to the effect that in India, “if you drive a car, you will find cars coming at you in all directions—but, somehow, we get there.” At ease operating in these conditions, Indians find that, in contrast, Americans like structure, plans, and systems—and this difference needs to be managed.

A List of Partnering Mistakes

Complementing the list of best practices for partnership was a list of partnering mistakes:

-

being a “possessive child,” Dr. Piramal’s label for an attitude characterized by everything from excessive protection of one’s own technology to erratic communication with one’s partner;

-

lacking trust;

-

failing to attract the best people;

-

picking the wrong “spouse”;

-

being vague about objectives and goals; and

-

stifling of an alliance’s growth by its “parents.”

Dr. Piramal then put forward a “Formula for Success” tailored specifically to undertaking partnerships in India. “Look before you leap” was a watchword: Indians’ aversion to the legal process, and their consequent adherence to the spirit as well as the letter of the law, underscored the importance of due diligence. “When you sign the agreement, you throw it away and really live for the spirit of it,” she explained. “We believe that legal fights are long and unpleasant and that business, like everything else in life, should be a joy.” Once a relationship is formed, it should be built gradually, with the partners focusing on common ground and shared goals. And since relationships can be reshaped over time, whether due to the exit of an original partner or a change in thinking that arrives with a new manager, structural adaptability is very helpful. “Being a farmer, not a hunter-gatherer,” an apparent recommendation to take the longer view, was the final element in her formula.

Allergan India: A Case of Indo–U.S. Collaboration

For a case study, Dr. Piramal turned to Allergan India, a 10-year-old joint venture of NPIL and the Orange County, California, company Allergan Inc. that had been nominated for the 2006 “Best Partnership Alliance” award by Scrip Magazine. This arrangement, which features “the leading Indian player working with the leading U.S. player” in ophthalmic eye care, has a strong foundation: The partners selected each other for values, purpose, and complementary

strengths. Even while taking advantage of mutual trust and credibility and of each other’s capacities—in technology and research, among others—to build, the partners “reinvented” their relationship every year through exchanging managers and expanding the joint venture’s agenda. The chairman of Allergan Inc., David Pyott, had called Allergan India “an excellent model demonstrating the benefits of collaboration between a global MNC and a strong Indian company.”

But was this success replicable? Could such alliances be the source of more earnings, and could they be depended upon for more growth? Dr. Piramal saw the keys as knowledge sharing, establishment of knowledge management, capture and dissemination of best practices, and alliance training. NPIL itself repeated its Allergan success with a second California-based company, Advanced Medical Optics, to build one of the largest custom-manufacturing relationships in India, as well as with two firms in the biotechnology sector, Gilead and Biogen-Idec.

Returning to her “Leadership in Action” model, Dr. Piramal said that what made the Call to Adventure of Indo–U.S. partnerships so interesting was the transformations they would further in both nations. Calling partnerships, particularly in joint development, a “strategic imperative for most firms” in the United States, she predicted that Indo–U.S. cooperation in the life sciences would increase.

To conclude, she screened a short video called “The Science Anthem” reflecting the renaissance of science in India.

Dr. Good thanked Dr. Piramal and praised her video both for its beauty and its potential for use in other venues. She then introduced Robert Armstrong, Senior Vice President for Discovery Chemistry Research and Technologies and Global External Research and Technologies at Eli Lilly and Co.—a firm that, she noted, has extensive interactions with India.

Robert Armstrong

Eli Lilly and Company

Thanking Drs. Wessner and Good for inviting him to speak, Dr. Armstrong said he would guide the audience through Eli Lilly’s approach to the strategic challenges facing U.S. business in recent years as it operated in the innovation space in Asia. Before taking this up, however, he declared his wish to warn against underestimating a company’s need to develop collaboration and understanding of its business internally as a prelude to reaching out and setting up external collaborations.

Being There: The Need for Acquaintanceship

To begin, Dr. Armstrong addressed under the rubric of “Communication in a Rapidly Changing Environment” the importance of comprehending the current dynamics of movement in Asia and, specifically, in India. He was, he said, forever

asking himself: “How often should I be on the ground in India?” There were new buildings and new products and new companies appearing all the time in this “very, very entrepreneurial environment”—an environment that, he believed, many in the pharmaceutical industry has not yet fully understood.

He recalled as a turning point for Eli Lilly a meeting of the company’s R&D executives that had taken place around two-and-a-half years earlier. Having been asked to give a presentation on Asia strategy, Dr. Armstrong arrived with a deck of 20 to 25 slides. The group made it no further than slide No. 1, however, owing to its lack of knowledge of issues ranging from the state of Indian science and the country’s intellectual-property regime to government funding for its labs and graduation rates for the scientists who would be feeding personnel pools for some innovation activities. Drawing what he felt to be the obvious conclusion, Dr. Armstrong turned himself into a travel agent and, for the next six months, worked to get his colleagues on the ground in India. That allowed Lilly’s executives not only to arrive at a degree of internal alignment—which was transferred to some actionable items in ways that he would explain—but also to speak with a single voice as they started to visit potential Indian partners.

The benefit was apparent at an R&D evening Eli Lilly held for pharmaceutical industry executives in 2005 that was attended by Dr. Piramal along with representatives of a number of other Indian firms. For the first time, according to Dr. Armstrong, the two sides began to see paths to innovation they could go down together that might allow them to leapfrog the more linear, traditional way of doing R&D. He would go into some of the details later on, then conclude by explaining how to put the “R” into “R&D.”

Vaulting Barriers to Productivity Growth

Displaying an April 2002 article from the Wall Street Journal with the headline “Why Drug Makers Are Failing in Search for New Blockbusters,” Dr. Armstrong remarked on how frequently one saw a version of the accompanying chart, which showed drug development costs increasing as the number of NCEs remained fairly flat. To prove the point,he posted a New york Times article, this one from January 2006, with a similar illustration.

Eli Lilly’s efforts to dissect and solve this problem had yielded a productivity equation that the company is using internally in which P represents “pipeline”; WIP, “work in progress ”; p(TS), “probability of technical success”; and CT, “cycle time”:

The equation, Dr. Armstrong explained, was a mechanism enabling a company to look at its “very large” pipeline and to achieve an understanding of whether it was full in accordance with historical expectations for delivery and

flow or instead contained gaps—and, in case gaps existed, to figure out what might be needed to fill them. Embedded in the numerator, along with the probability of technical success, was a Value component attached to the disease state and modality in question: The latter could be aimed either at ameliorating some of the side effects of the former or at going after its fundamental causes. The denominator, in addition to cycle time, contained a component reflecting the Cost of running the entire drill.

India’s Role in Improving Productivity

Although every term of the equation has relevance for increasing productivity, Dr. Armstrong chose to focus on those that might elucidate Eli Lilly’s thinking on the issue and, in particular, on the role it saw India playing. All the activities of the pharmaceutical industry’s R&D sector can be broken down into two components and placed on two axes—the x-axis representing technical difficulty on a continuum from hard to easy, the y-axis ownership on a continuum from proprietary to nonproprietary—so that the origin of the axes marked the confluence of the highest difficulty with the greatest ownership (see Figure 6).

Among the factors determining the position of research activity along the x-axis might be coordination of multiple scientific and medical backgrounds, level of experience in a particular area, and the status of activities that might

FIGURE 6 Implications of project difficulty and know-how on external partnering arrangements.

have been very innovative at one time but had become industrialized to the point of having converted to standard operating procedures. Dr. Armstrong’s comment regarding the y-axis was that India’s embrace of intellectual property rights protection both enables multinationals to consider undertaking innovative activity there and created value for local industry. As evidence of the latter point he offered the investment in innovation that is beginning to be made by such companies as NPIL to target diseases that affect India’s region and thereby meet the medical needs of its population.

Running through Eli Lilly’s analysis, Dr. Armstrong noted that pharmaceutical industry R&D activities tended to be judgment-based at their debut but evolve over time so that they became rule-based. The question before the company was which levers in a productivity equation could be affected so as to ameliorate such factors as cost and cycle time. The industry, motivated largely by a desire to drive down the former, has so far considered outsourcing for what it perceives as rules-based activities and, in his opinion, has been successful in so doing. However, what has been eye-opening for the Western pharmaceutical industry—even if it was hardly surprising to the companies providing the services—is that a “huge” component of cycle-time reduction has also been involved. “Embedded in that cost reduction is a lot of innovation in processes and focus in delivering products,” he explained, “so that outsourcing or outlicensing activities previously occurring inside the company has changed the equation on cycle time for many of them.”

Spreading Knowledge Within the Company

The degree of appreciation for this relationship varied even within Eli Lilly, as some who attended the meeting of R&D executives previously mentioned had already engaged in collaborations with India. Like all global pharmaceutical majors, Lilly had been active in India for years, teaming with a number of companies there both on the manufacture of many legacy products that still carried its own brand and on the launch of global clinical studies. So, some groups within the company were quite familiar with the concept of outsourcing to increase productivity and had seen it validated in India. But others, especially those involved in early development, remained hesitant about a global model that called for transferring next-generation activity abroad and, in general, embracing innovation wherever it might occur. The company was, however, making substantial inroads in that direction.

Alliances: Not Only Cost-Cutting Vehicles

Over the previous decade, in fact, research alliances had been Eli Lilly’s primary mechanism for addressing cycle times, and the company had benefited from process changes and technology achievements made by some of its partners. But

in addition, Dr. Armstrong stressed, alliances are becoming vehicles for improving the probability of technical success.

In quest of the latter, Eli Lilly has invested in the firms with which it is allied, not only in the area of manufacturing innovation but also, as he put it, “in true innovation, at the front end of the pipeline feeding the R&D engine.” To date, these research alliances have been with biotech companies in the Boston, Seattle, and San Francisco areas; around Cambridge and Oxford in the United Kingdom; and in Germany.

But on their continuing visits to Asia, and in particular to India, Eli Lilly officials were being reminded by the numerous start-ups they were seeing of what they had observed a decade before in San Diego and five years before that in San Francisco and Boston. Beyond mirroring the entrepreneurial achievements of those areas, where the risk taking of start-up companies was often quite well financed, Indian start-ups were taking on problems that lent themselves to “leapfrog solutions.”

A saying current at Eli Lilly—“we do discovery and development without walls”—is intended to convey that the company could not expect to do everything on its own. Finding partners it could work with is therefore regarded as key, and Dr. Armstrong and his colleagues see India as providing global pharmaceutical companies in the coming years with “very fertile ground” for true collaboration, particularly in the innovation space.

Simultaneously with a trend in the sector toward moving activity out when that might get it done in a more time-efficient fashion or at a lower cost, an opposite and perhaps more important trend is emerging: Partnerships are increasingly in evidence at the early stages of innovation. Not only are companies in the R&D services or materials procurement sectors “moving their way into the discovery component,” but stand-alone biotechnology firms whose mission at start-up has been to operate in highly proprietary and technically difficult areas are also forming alliances. Eli Lilly is spending a great deal of time assessing companies worldwide in an effort to identify those it might want to collaborate with on pilots or experiments, and Dr. Armstrong predicted that, as the sphere of partnership activities develops and matures, Lilly would be able to pursue productivity improvement by tapping into these partnerships more effectively.

A “Mosaic of Innovators” in Pharma’s Future

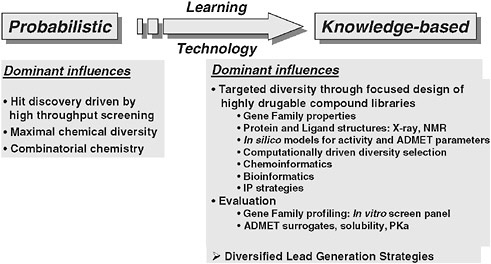

To help illustrate how the changing distribution of skill around the world is affecting the way the industry does business, Dr. Armstrong displayed a chart (Figure 7) highlighting a number of chemical starting points and some of the issues surrounding them.

There were many companies in Asia, including in India, “that map very nicely to a large number of components of how we think the next generation of chemical starting points is going to occur in the pharmaceutical industry,” he said.

FIGURE 7 Example: Identification of chemical starting points.

In keeping with the evolution of drug discovery at Eli Lilly, the company intends to put together a “mosaic of different innovators” that would allow it to address productivity improvement throughout the process of innovation.

To conclude, Dr. Armstrong stressed how fortunate Eli Lilly has been in having conversations at a very high level with a large segment of India’s pharmaceutical industry and in achieving a thorough grasp of both the opportunities and the challenges facing the companies that these Indian companies represent. At the same time, he and his colleagues have been grappling with a challenge of their own: trying to achieve an alignment inside Lilly that would better enable it to work in the innovation space on a global basis.

Dr. Good, offering Dr. Armstrong enthusiastic thanks for his presentation, presaged the following introduction with the observation that, while 25 years before the word global was scarcely to be seen in the corporate title of an R&D official, it currently figured in most of them. This was exemplified by the next speaker, Kenneth Herd, who had recently been named Global Technology Leader for the Materials Systems Technologies at GE Global Research.

Kenneth G. Herd

General Electric

Outlining his talk, which would focus on GE’s efforts to nurture cooperative ventures in R&D bridging the United States and India, Dr. Herd said he would begin with a brief overview of GE and of its Global Research organization. He would then turn to GE’s activities in India, both past and present, before specifi

cally reviewing GE’s involvement in R&D there and concluding with a discussion of some of its achievements, opportunities, and challenges.

GE is organized into six businesses serving customers at the industry, market, and national levels, which Dr. Herd listed with their focuses:

-

Health care: diagnostic imaging, clinical systems, information technology, services, biosciences;

-

Infrastructure: aviation, energy, rail, water, oil and gas;

-

Industrial: consumer, plastics, silicones, security and sensing, equipment services;

-

Commercial finance and consumer finance: insurance, leasing, financial services globally; and

-

NBC Universal: TV and radio networks and stations, entertainment, sports.

With operations in more than 100 countries, GE has a workforce exceeding 300,000 and, for 2005, earnings of around $16.6 billion on revenues of $155.4 billion. “We are very proud to be the only one of the Dow Jones Index’s six original companies that is still listed on it,” he said.

The Evolution of Research at GE

GE Global Research has evolved from one of the first industrial research labs in America into a highly centralized R&D organization that is among the world’s most diverse. Begun in 1900 in a barn behind the Schenectady, New York, home of Charles Steinmetz—a brilliant GE electrical engineer who recognized R&D’s critical importance to the development of commercial products—it has since grown steadily into a truly global presence. The John F. Welch Technology Center in Bangalore, to which Dr. Herd would return in a moment, became GE Global Research’s first technology center outside the United States when it opened in 2000. Its China Technology Center, opened in 2003 in Shanghai, currently employed about 1,200; GE Global Research–Europe, which opened the next year in Munich, had around 100 employees.

GE in India: A Long History

GE’s business experience in India began when it installed the country’s first hydropower plant in 1902, and all GE businesses have been present since 1998, representing a wide range of activities in manufacturing, services, and technologies. The company has more than 12,000 full-time employees and $2 billion in assets in India, and, in 2005, posted revenues of $1.4 billion while exporting $1 billion in products and services. Just two weeks previously, on May 30, 2006, GE Chairman Jeff Immelt had announced in a speech to the Bombay Chamber of

Commerce that the company would invest $250 million in infrastructure, health care, and real estate in India. Its current goal was to acquire $8 billion in assets in India and reach an annual level of $8 billion in revenues there by 2010 through activity in health care, cleaner energy, clean water, and aviation.

Today’s Attraction: Intellectual Capital

Most compelling among the reasons for GE to develop R&D capability in India is the country’s strong intellectual capital, as embodied specifically in its talent pool of engineers and scientists. India’s 200-plus national laboratories and 1,300 industrial-sector R&D units employ approximately 200,000, and, owing to India’s more than 300 universities, the student pipeline is very strong as well. An R&D presence enables GE to attract India’s best global talent and apply it to critical technology development in existing and emerging markets. In return, GE is in a position to invest in training and developing world-class talent in India and to offer jobs that would attract great Indian talent back from abroad.

GE’s Bangalore Technology Center

GE’s technology center at Bangalore, an $80 million investment, comprises 500,000 square feet of facilities that are spread across a 50-acre campus. Employing approximately 2,500 engineers and scientists—over 60 percent of them with advanced degrees and 20 percent with global experience—its state-of-the-art laboratories conduct research and development in many disciplines: mechanical engineering, electronic and electrical system technology, ceramics and metallurgy, catalysis and advanced chemistry, chemical engineering and polymer science, new synthetic materials, process modeling and simulation, and power electronics and analysis. Based there in addition to a Global Research technology team are teams from other GE organizations: Healthcare, Plastics, Silicones, Water Technology, Energy, Consumer & Industrial, Aviation, and Rail. These groups of engineers and the technologists work together to transition and deliver technologies out to GE’s businesses.

To date, the Bangalore center had filed over 370 patents, 44 of which had been issued, something the company is very proud to have achieved in less than five years. Among the center’s recent technology successes:

-

GE Healthcare: diagnostic-imaging breakthroughs for computed-tomography and magnetic resonance products;

-

GE sensing: phased-array ultrasound system developments for inspecting critical aircraft components, as well as next-generation pressure sensors; and

-

GE Plastics: high-performance plastics solutions for the automotive sector.

GE Technology in India: Four Phases of Development

The development of GE’s technology efforts in India can be viewed as having gone through four distinct phases:

-

a period of contract engineering during which the predominant activity was the outsourcing of engineering analysis and modeling tasks to non-GE businesses in India;

-

the decision to establish a foothold in India by building a solid technology foundation there, which led to the engagement of senior leadership across the corporation in investing in the John F. Welch Technology Centre as a key resource. Dr. Herd acknowledged the “significant support” GE had received from one of the day’s earlier speakers—R. A. Mashelkar, the director general of the Council on Scientific Industrial Research—in the center’s start-up and launch;

-

the process of recruiting and staffing the center with “the world’s best,” which had begun with identifying the centers of excellence that would reside in Bangalore, progressed to hiring a mix of experienced and recent graduates across a range of disciplines, and continued with significant investment in the training and mentoring of the new teams, which were active along a wide spectrum of global technology programs in vital areas; and

-

reaping the fruit of these collective efforts, the phase that is currently in progress. “Unique intellectual property and design concepts are being generated, and the infrastructure and processes are in place to drive GE’s strategy of growth through technology,” he said, describing the company as also very well positioned to develop technology for the markets emerging in India and the region in aviation, energy, rail, health care, consumer products, and water technology.

As with any new venture, the launch of GE’s global R&D programs has faced challenges. While there was much concern at first about work shifting out of its U.S. labs, Dr. Herd recalled, GE has continued to strengthen them while significantly expanding its collective technical breadth by growing its labs abroad—without whose addition, he maintained, GE would have been unable to keep up with its growing technology needs.

Lessons Learned from GE’s Indian Experience

He concluded with a list of lessons that GE had learned from its involvement in India:

-

that global teaming is not intuitive but requires training, tools, and a cultural shift whereby both sides meet in the middle. “In fact,” said Dr. Herd, “global teaming has added a whole new dimension to our careers—the experi-

-

ence of bridging global divides, exploring new cultures, addressing global challenges—and continues to be a very enriching experience for all involved.”

-

that schedule flexibility is very important to accommodating time-zone differences. Dynamic work hours, global video conferencing, early-morning and late-night teleconferences, and global travel had become an integral part of GE’s routine.

-

that linkages among sites are absolutely critical. GE had found that by first defining core competencies or centers of excellence at its global labs, then linking them to adjacent centers of excellence in the United States, it could avoid redundancy and competition among its labs abroad while leveraging the experience and network of its existing domestic teams.

-

that retention correlates with the vitality of work. When the global teams are energized by their work, they have a direct line of sight to its product applications, and retention is high. In contrast, when work is of lower quality, vitality, and visibility, retention is understandably poor. GE’s highest priority was building high-impact, high-visibility programs at its global sites, an important challenge these sites were in the process of taking on.

-

that start-ups take time. Building and training the teams, making the organizational and cultural shifts, and “hanging in there” have really paid off, said Dr. Herd. Equality of skills, visibility, engagement, and vitality of innovation were becoming reality. As a researcher and technology leader at GE, he had seen personally that the R&D landscape is accelerating rapidly both in India and on a global scale. “We are very fortunate to be a part of this very exciting frontier,” he concluded.

Dr. Good, thanking Dr. Herd, reflected that while each firm had found its own structure for partnership, all were improving their business positions—an indication that the diverse structures were working. “That’s probably as straightforward as we can get,” she remarked, before introducing Ponani Gopalakrishnan, former Director of the IBM India Research Laboratories, as a man with a great many friends in both the New York IBM community and Washington.

Ponani S. Gopalakrishnan

International Business Machines

Dr. Gopalakrishna expressed his gratitude to the audience for staying so late in the afternoon and pledged to do his share by trying to measure up to the level of the brilliant and informative talks that had preceded his. He would offer a brief view of IBM’s experience in running what was probably “one of the only information technology pure research organizations in India,” which was founded in 1998 and pursued technologies for the next generation of the company’s products and services.

Investment to Increase IBM’s Indian Presence

The organization that Dr. Gopalakrishnan’s headed is part of an IBM “fairly strong” presence in India. This presence is likely to grow stronger still as the result of a planned $6 billion investment in the country that IBM made public only 10 days before the day of the National Academies’ conference. In conjunction with that announcement, President A. P. J. Abdul Kalam addressed a gathering of about 10,000 IBM employees in Bangalore, while 20,000 of their coworkers in cities such as New Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, and Calcutta saw him speak via videoconference.

IBM India spans not only these cities but also a spectrum of functions, from software and systems development to the pure, long-term research done by the organization Dr. Gopalakrishnan headed. IBM’s R&D personnel in India number more than a couple of thousand, in addition to whom there was a large contingent of employees delivering information technology services and IT-associated services to a worldwide client population.

Profiling IBM R&D in India

IBM India Research Laboratories itself has a little over 100 very highly skilled researchers working as part of a team of about 3,200 that is spread over the IBM Research Division’s eight labs worldwide. The lab in India has the same mission as many of the others—to advance the state of the art in information technology—while working primarily on software and services-related research, and taking into account local and global priorities alike. Its essential focus, however, is to provide leadership for the future both to the IBM operations in the region and to the company’s clients and partners both in India and globally.

IBM India Research Laboratories has its headquarters in New Delhi and a team in Bangalore conducting research directed toward the company’s services organizations. Dr. Gopalakrishnan named key areas in which the labs are engaged, cautioning that the list is representative rather than exhaustive:

-

Information management. Enterprises increasingly find that internal data are no longer stored exclusively in regular relational databases but in multiple forms that include e-mails, text messages, PowerPoint presentations, and the like. The problem of capturing the information and gathering intelligence from these varied data is being addressed through research into the integration of information from structured and unstructured sources.

-

Software engineering. Tools, methodologies, process optimization, and modeling were among the fields of inquiry.

-

User-interaction technologies. Work is in progress on speech-recognition technology applying to the local languages of India, Hindi, and Indian-accented English—the latter’s being, for this purpose, “a different language,” Dr. Gopalakrishnan said.

-

Services research. Begun in Bangalore late in 2005, this work is being carried on in conjunction with that of IBM’s services delivery teams and was focusing in particular on issues arising in IT-enabled services. He called the activity “pioneering” in that R&D has traditionally been associated with products but a “strong component” of the technology involved in product research could be applied to the services as well, an endeavor whose potential IBM is starting to investigate. Among the areas being looked at by the Bangalore team are process modeling, system resiliency, knowledge-management platforms, and infrastructures for maintaining knowledge-workforce management. A paradigm similar to that applied to a parts supply chain might be applied to human-skills management as long as completely different methodologies and approaches to modeling were taken.

This work is being pursued in close collaboration with what he referred to as IBM’s “global technical ecosystem,” which includes not only the company’s seven other research labs but also its partners elsewhere in industry and in academia.

He then showed a brief video designed to portray the scope of IBM India Research Laboratories’ efforts in these domains. The video focused in part on a current project in which the labs were laying foundations for a very secure network conceived in accordance with the realities of India’s information technology infrastructure. Groundwork for this project began with a “fairly thorough analysis” of the information-sharing needs of India’s health-care entities, which range from large hospitals with very sophisticated IT systems to 10-bed clinics run by a pair of physicians that might have no IT system at all. The network would attempt to take into account such diverse requirements.

IBM’s Four “Secrets of Success”

Reflecting on his experience, Dr. Gopalakrishnan raised the question of whether IBM could expect its technological research and innovation in India to match the level and quality of that conducted in many of the research labs it operated elsewhere. “The answer is a definite ‘yes,’” he declared, imparting four “secrets of success”:

-

Address the right problem. In an industrial research lab, this meant making sure researchers focus on the problems that would eventually generate the broadest business or social impact, a point he would return to in No. 4.

-

Build the right skills. IBM India Research Laboratories works very hard to attract and retain talent with wide international experience—talent equal to that at any other IBM research lab. Fully 50 percent of its researchers had Ph.D.s and, of those, 50 percent had earned them in the United States; Dr. Gopalakrishnan himself was a product of the University of Maryland–College Park. The permanent research staff is supplemented through a regular program of academic

-

visitors who stay for between three months and a year and through internships offered to university students from countries around the world, including the United States, Australia, and India itself.

-

Encourage collaboration. Many of the lab’s projects involve collaboration with researchers, both within IBM and outside, from other parts of the world.

-

Ensure broad impact. The practical significance of their work is what gives researchers the satisfaction that keeps them motivated.

India has certain unique market requirements that make for very interesting design points, Dr. Gopalakrishnan said, one example being seen in the fact that it offers the lowest-cost GSM cellular phone service in the world. Invoking C. K. Prahalad’s book The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits, he noted that there are compelling arguments for designing systems and solutions for consumers at the lower end of the market—not for philanthropic or charitable reasons, but because real money is to be made there. An analysis of affordability and utilization suggests interesting technologies that could be used to develop systems that allow very high volume access at low cost. IBM India Research Laboratories is itself embarking on a project aimed at providing information technology to the lower end of the economic pyramid.

Potential Areas for Expanded Indo–U.S. Collaboration

Considering potential areas for expanded collaboration, Dr. Gopalakrishnan speculated that the extensive technology base embedded in the U.S. universities and in its other research organizations might serve as a source upon which Indian industry could draw as it addressed the challenge of taking on international scope. Great value might also be found, as all tried to deal with what was a growing pool of research, in coming together to focus on some grand challenges. He put forward as an example the aforementioned health care data network: India’s greenfield environment holds the potential for experimenting with technological capabilities and possibilities that could be applied to U.S. systems as well.

In conclusion, Dr. Gopalakrishnan offered his own opinion that there are significant opportunities for collaboration currently available. He also drew attention to the remarks made 10 days earlier in Bangalore by President Abdul Kalam, in which he outlined a compelling vision: “the creation of a World Knowledge Platform for realization of world-class products for commercial applications using the core competencies of partner countries which will meet the needs of many nations…. Initially, the mission of [the] World Knowledge Platform is to connect and network the R&D institutions, Universities and Industries….”

Dr. Good then introduced the day’s last speaker, M. P. Chugh of Tata AutoComp Systems (TACO), who is based currently in Troy, Michigan. She noted that Tata, TACO’s parent, is one of India’s largest diversified companies.

M. P. Chugh

Tata AutoComp Systems

At the risk of disappointing the audience, Mr. Chugh said, he would admit that he was neither a scientist nor an R&D professional but a “simple businessman” preoccupied with return on investment. Then, recalling a statement made earlier in the day by Dr. Kapur about the importance of “return on innovation,” he raised the question of what innovation really is. According to Tom Peters, innovation is never created in institutions, but always by breaking the rules. Offering the examples of Google and Microsoft, which had broken many of their industries’ rules—or had, at least, violated many conventions—Mr. Chugh reiterated his uncertainty about the nature of innovation and of R&D, as well as about the role institutions played in them.

After profiling the 29-company Tata Group and the unit he himself represented, Tata Auto Components (TACO), Mr. Chugh said that he would enumerate the lessons learned from U.S.–Indian cooperation on what he called “development and engineering,” drawing mainly on the group’s involvement in Tata Johnson Controls. He would then touch briefly upon an ongoing U.S.–Indian R&D project with which he had been associated and, to conclude, address the opportunities that Tata believed were offered by cooperation.

The Tata Group: India’s General Electric

Known to some as the “GE of India,” the Tata Group is the source of 5.1 percent of the country’s exports and 2.8 percent of its GDP. One of India’s largest conglomerates with interests in the automotive, steel, power, chemical, information technology, tea, coffee, and hotel sectors, it employs 215,000 workers and posted turnover of $17.8 billion in its 2005 fiscal year. Its total market capitalization of $41.4 billion was accounted for by shares in the hands of 2 million people.

The structure of the Tata Group’s ownership made it what Mr. Chugh called “a great example of innovation in an institution.” All Tata Group companies were held by two “promoter” companies, Tata Sons, which has the group’s main operating companies under it, and Tata Industries, which promoted the group’s entry into new businesses. Ownership of these two entities breaks down as follows:

-

Tata Sons is held 66 percent by two public trusts, the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust and Sir Ratan Tata Trust; 18 percent by external shareholders; 13 percent by other Tata companies; and 3 percent by the Tata family.

-

Tata Industries is held 29 percent by Tata Sons; 52 percent by other Tata companies; and 19 percent by the Jardine Madison Group.

The two public trusts provide endowments for the creation of such national institutions as the Indian Institute of Science, which dates to 1911; the Tata Insti-

tute of Social Sciences, 1936; Tata Memorial Hospital, known for the quality of its cancer research, 1941; the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, 1945; and the National Center for the Performing Arts, 1966. In addition, the trusts funds companies committed to spending nearly $100 million per year on social welfare, sponsoring volunteer programs, and similar activities.

Tata’s Innovativeness in the Auto Sector

Among the group’s industrial innovations is Tata Motors, which has recently made the transition from a specialist in diesel-powered commercial vehicles to a successful automaker. When group Chairman Ratan Tata announced his desire a decade earlier to make passenger vehicles, “everyone laughed,” Mr. Chugh recalled, “telling him: ‘Very few companies can make cars in the same culture and mindset that makes buses and trucks.’” The Tata Group head nonetheless pledged that the firm would do it—and do it on its own—with the result that Tata Motors is currently either second or third on India’s auto market with a 28 percent share. At the heart of this effort was the company’s engineering research center, which either developed or adapted innumerable technologies for use in Tata’s vehicles.

Profile of Tata Auto Components

A second innovation announced by Ratan Tata in defiance of skepticism from “bigwigs” is a $2,000 car, test models of which are already running. Tata Auto Components, which Mr. Chugh represents, is deeply involved in this endeavor, looking at component-level technology around the world. When TACO was formed in 1996, India did not have the cutting-edge technologies required; in fact, its component industry was so fragmented it could not provide products at anywhere near world-class quality. Now, however, TACO has 16 global partners, four engineering centers, and 16 plants; is focused on building exports; and has been referred to as the Delphi to Tata Motors’ GM. He noted that TACO has a fiercely independent structure, being at times obliged to work harder than its competition to sell to Tata Motors because “there is always an internal rivalry.” The secret of its success has been learning diverse technologies and offering complete program management capabilities.

To indicate the extent to which TACO has acquired knowledge and enhanced its research and development—as well as its “innovative spirit”—through joint ventures, Mr. Chugh named a few of the company’s U.S. partners:

-

Johnson Controls Inc. (JCI), for seating systems;

-

Owens Corning, for sheet-molded composites;

-

Visteon, for lighting and engine induction systems; and

-

Hendrikson, for bus and commercial-vehicle suspension systems, in a venture that had yet to go into production.

He also offered a quick panorama of TACO’s product areas: interior plastics, seating systems, exteriors and composites, wiring harnesses, telematics, sheet-metal assemblies, engine cooling, exhaust systems, mirrors, control cables, springs, braking systems, and, new in 2006, batteries, CV suspensions, lighting, and engine induction.

Leveraging Indian Talent to Serve Global Markets

A unique business model runs as a common thread through all of TACO’s endeavors, he said, formulating it thus: “Not only use the engineering talent in India, but leverage the engineering talent in India for a global business market.” The model’s key success factor is engineering competence. TACO currently employs over 800 engineers—a figure expected to rise to 1,500 in 2007 and to 2,500 in 2008—spread over four facilities: its own TACO Engineering Center and three jointly held with partners, Tata Johnson Controls Engineering Center, TACO FAURECIA Engineering Center, and TACO Visteon Engineering Center. Noting that JCI, FAURECIA, and Visteon compete fiercely among one another in some sectors of the auto components business, Mr. Chugh said that TACO is able to manage relationships with all three successfully because of the core strength in engineering and product development that it brings to the table.

A Collaborative Model: Tata Johnson Controls

As an illustration of how the collaborative model has been applied, he chose the engineering division of Tata Johnson Controls (TJC), the first company in which it has been tried and the only one in which it was completely mature. A venture owned 50 percent each by TACO and JCI in keeping with Tata’s “respect for partnerships” and preference for joint contribution over unilateral control, TJC has 400 employees worldwide and 2005 sales of $16 million in engineering services alone. In addition to running one of the largest dedicated automobile product design centers in India, the joint venture has an engineering center colocated with JCI in the United States that employs 55 engineers and is headed by Mr. Chugh himself, as well as some 150 engineers in Europe and 40 to 50 more in Japan. In all parts of the world, the design and development work done by the venture across the fields of automotive seating, interiors, and electronics is determined by JCI’s own requirements.

The key to TJC’s success lies in coordinating the efforts of engineers spread around the globe as they carry on work on a given product development program around the clock—something with which it had had great difficulty in the two years immediately following its establishment in 1995. To overcome this challenge, JCI adapted its business operating system, working with a TJC engineer on site to execute processes that ensured communication between India and other lo-

cations. Although this model is much harder to implement in design engineering than in information technology, it has nonetheless been extremely successful.

Anatomy of a U.S.–India R&D Cooperation

Mr. Chugh then described a cooperative R&D project in the safety and electronics field that TACO has entered into with a U.S. partner. This partner’s current product/service model applies exclusively to high-end market needs in the United States and Europe—he characterized its segment as one that might include Mercedes or BMW—and most of its offerings need to be adapted considerably for regional functionality and regulatory requirements, particularly since the latter differs greatly between the United States and Europe. The project calls for joint development of a low-cost, global platform capable of being:

-

Manufactured in a low-cost country (LCC). “Electronics products can be made in Thailand or China much more cost-effectively than even in India if it’s a mass run,” he said, adding that TACO would “definitely” consider production outside India.

-

Rolled out in most markets with minimal adaptation. “On the hardware side it’s going to be a modular product,” he explained, “and on the software side there’ll be nothing sitting on the hardware.” Using the case of a telematic product as an illustration, he said that suites of services in different price ranges might be available for loading onto the product.

The design phase of this project had just been completed, and the partners expected the rollout to take place soon. To exemplify TACO’s existing R&D work, he provided a few examples of air vents it had designed. Two patents—one on an air vent for MG Rover, the other on universal mechanisms for air vents—dated to October 2005, while a third patent, on an air-vent mechanism for a vehicle yet to be launched, the X1, had been filed in March 2006.

TACO’s Opportunities and Aspirations

TACO sees its opportunities for research and development in interiors, electronics, safety, and emissions. As is the way of the automotive industry, the company takes its cues from its customers rather than doing original research. It inquires as to their problems and goes back to the lab in search of solutions, hitting (in the process) upon patentable discoveries or novel applications. TACO’s aspirations, Mr. Chugh indicated, are global; the company believes it needs to be not only in China, India, and the ASEAN region but also in the markets of the United States and Western Europe, all of which are looking for low-cost country sourcing.

Although low-cost country sourcing might seem to be a “shoot-and-ship kind of idea,” that is not the case, Mr. Chugh said, because at its core is engineering

design. TACO is getting contracts from the U.S. Big Three automakers who say, “Here is a black box,” which means: “I’ll tell you only the space, and you design the part. Give me prototypes that are tested and validated, then manufacture it and send it to us.” While the Chinese are much more cost-effective at doing just the shoot and ship—that is, providing a drawing and design—TACO’s unique selling proposition is its ability to do everything in the same package. In fact, design capability is TACO’s core strength. Its future will be devoted to building a deep engineering and R&D base that can enable it to develop technology and innovative solutions for its customers, which is its constant focus.

Policy Making for Economic Opening: A Personal Account

Having finished his presentation on Tata’s activities, Mr. Chugh asked the audience’s indulgence as he shared a personal experience from around 10 years earlier, when he worked for ICICI Bank, formerly ICICI Ltd. India. He had joined that financial development institution in 1975, when it was engaged in the first export development study, which was funded by the World Bank. ICICI did a second such study several years later, but even then the government’s policy was not ready for it, and it was put on the shelf with its predecessor. The concept entered into play around 1986, when rumblings regarding a liberalization similar to that which was to begin in 1991 were heard in government circles. In 1990, another export development program was drafted, and that one was to run for about 10 years.

Mr. Chugh explained that he was bringing this to the attention of the audience as an interesting example; the World Bank had called it the most successful such program ever involving cooperation among multiple agencies. Its diverse stakeholders ranged from government financial institutions to research and development institutions and from industry to academics and other individuals. The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) had been among the partners, and Dr. Mashelkar had been associated with the program as well.

Mutual Benefit as the Platform for Change

The ICICI initiative owed its success to several elements. Upon the joint initiative of the World Bank and the Government of India, a policy framework was created by the Bank itself. Incentives were set up for all involved: ICICI had no interest in assigning 10 people to an export development program, nor did the government care to put up money, unless there was to be some benefit. Since at that time India had a shortage of foreign exchange, the World Bank provided funding on the condition that the policy initiatives be put in place—which meant that the economy had to be opened up. Ataman Aksoy, a World Bank economist whom he remembered as having done a “fabulous job,” sat with Mr. Chugh and, together, they looked at everything that might be done in pursuit of that goal.

Synchronizing Public and Private Incentives

When implementation began, however, there were innumerable glitches. The approach demanded was simultaneously top-down and bottom-up. As to the former, every project brought to the table required a government initiative at the policy level if change was to occur. Reserve Bank of India (RBI) guidelines might, for instance, prevent a foreign technician from being brought in for a particular R&D project. In response, a steering committee was created on which were represented major institutions: the secretary (commerce), the secretary (finance), RBI, the Ex-Im Bank, and ICICI. The World Bank was extremely helpful in putting pressure on the government.

The bottom-up element consisted of microlevel intervention on a project-by-project basis. As an illustration, nobody at the time wanted to look at ISO-90007; it was hard to get even one company to send people to the lead assessor program being run by CII’s Total Quality Management division. Mr. Chugh recalled doing something “that no banker does: double financing.” CII was financed to set up the program, and companies were given 50 percent matching grants—“ ‘gambling money,’ as Dr. Mashelkar put it”—to send their employees. What this produced was not so much a trickle-down effect as a “blowing-up effect,” in the sense that companies had become so enthusiastic that they were currently willing to pay for the program on their own.

This was not the only sort of intervention to occur. When Hindustan Motors, having built a huge factory in Hallol (since taken over by GM) announced its intention to set up a joint venture with a foreign partner to manufacture trucks, the International Finance Corporation in Washington put its foot down. Hindustan Motors was told it had to fix its Ambassador passenger car business, which was on the skids, before it could get involved in trucks.

Serving Innovation by Breaking the Rules

“We brought in consultants, we brought in experts from overseas, we broke almost every rule in the game,” Mr. Chugh said. “And that is the kind of innovation with which I’m very proud to be associated, earlier with ICICI and now with Tata.” For innovation, he maintained, was not only a matter of organizations, whether smaller or larger; it resided, as Dr. Mashelkar had said, in the leadership, or entrepreneurship, or technopreneurship. “Call it whatever you want,” he concluded. “It’s the people who make the difference.”

Dr. Good, observing that in view of the hour the closing reception would have to double as the question period, expressed her regret that the government ministers attending the symposium had been unable to stay until its end. A pair

of important insights had emerged from the presentations offered by the business people on the final panel: that partnerships will not work if they are one-sided but must be built on mutual advantage; and that when the innovation engine of private enterprise is turned loose, it gets ahead of policy relatively fast. Thanking the speakers for sharing extraordinarily interesting case studies, she turned the microphone over to Dr. Wessner for final comments.