Panel II

Synergies and Gaps in National and Regional Development Strategies

Moderator:

Praful Patel

The World Bank

Dr. Wessner welcomed the panel and its chairman, Praful Patel, the World Bank’s vice president for South Asia. Before ceding the podium to Dr. Patel, Dr. Wessner praised him for devoting his life not only to studying the questions before the panelists but, “even better, to doing something about advancing the development agenda in India and elsewhere.”

Dr. Patel greeted the audience with the observation that the opening panel, in its focus on the bigger picture, had provided extremely good background for subsequent sessions. He observed that the theme of this panel, “Synergies and Gaps in National and Regional Development Strategies” is very closely aligned to the ongoing work of the World Bank and the government of India. Given the exciting progress on this topic, he said that he was pleased with the prospect that this panel would add to his knowledge.

Dr. Patel pointed to the presence among the panelists of Carl Dahlman, the lead author of India and the Knowledge Economy, a report published by the World Bank in 2005 that was of consequence for the day’s discussions,5 and to the presence in the audience of R. A. Mashelkar, who was to speak on a later panel. A workshop to be hosted on July 4 by India’s Council of Scientific and

Industrial Research (CSIR) under Dr. Mashelkar’s leadership was to take up the initial findings of the Bank’s report.

Introducing all three members of the panel in order of appearance, he started with T. S. R. Subramanian, who has retired following a distinguished, 37-year career with the government of India during which he had held its highest civil-service position, Cabinet Secretary to the government of India. Then would come Dr. Dahlman, currently Luce Professor of International Affairs and Information Technology at Georgetown University, who had distinguished himself during more than 25 years at the World Bank, where he and Dr. Patel had been colleagues. The final presenter was to be Surinder Kapur, who was participating in the capacities of both chairman of the Confederation of Indian Industry’s Mission for Innovation in Manufacturing and of founder chairman and managing director of the Sona Group. Dr. Patel assured the audience that what Dr. Kapur had to say about the group’s activities would be very exciting and especially germane to the topic of how innovative technology’s impact can be scaled up to reach large numbers of people on the ground.

Dr. Patel suggested that each of the speakers take no more than 15 to 20 minutes, so that time was certain to remain for questions from the floor. With that, he invited Mr. Subramanian to the podium.

BUILDING REGIONAL GROWTH: ELEMENTS OF SUCCESSFUL STATE STRATEGIES

T. S. R. Subramanian

Government of India (retired)

Thanking Dr. Patel and greeting his fellow presenters and the audience, Mr. Subramanian said he would begin where Mr. Ahluwalia had left off by addressing areas for further action. The broad theme for the present panel could be the subject of numerous separate presentations, each of which might approach it from a different direction: by considering questions of national versus state government; urban versus rural; industrial, service, or agrarian policy; even regional and subregional development. Additionally, it could be addressed from the point of view of the entire framework of government policy, comprising policies of the central and state governments alike, or by asking whether the policies of the state governments were in conformity with those of the central government. He proposed to touch, however briefly, on some of these areas.

For the benefit of those lacking familiarity with the Indian system of governance, Mr. Subramanian noted that, as in the United States, the Indian Constitution clearly demarcates the powers and responsibilities of the central government from those of the state governments. Most of what touches the average citizen, including law and order, education, public health, and rural development, is in the purview of the states. Much of the reform to date had related to areas

within the purview of the central government, such as monetary and fiscal policies.

Given that Mr. Ahluwalia had evoked India’s successes, as exemplified by the high average annual growth rate achieved since the introduction of liberalization reforms, and because these very real successes are well documented, Mr. Subramanian said that he would not dwell on them. Instead, he would “zero in straightaway on the dark side not generally highlighted in the euphoria of India’s great progress”: the arena of human development, where the numbers, he asserted, were “terrible, to say the least.”

After nearly 60 years of self-rule, more Indians are now below the poverty line—which Mr. Subramanian called “a euphemism for saying they’re desperately poor, they don’t know where the next meal is coming from”—than at independence. The divide between urban rich and rural poor has dramatically increased. The majority of the population in most urban areas, including metropolitan areas, consist of slum dwellers, the average being about 55 percent for the country as a whole—“slum dwellers,” as he characterized them, “in the glittering cities.”

That urban areas act as magnets despite the harsh conditions they offer the poor is indicative of the lack of job creation in the rural context, Mr. Subramanian suggested. Whereas primary education is universal and compulsory, only 16 percent of the population complete high school; just doubling that number would have a significant impact on the base for information technology (IT) development. Meanwhile, public health is in bad shape, with rural facilities “abysmal.” The micronutrient level in the human diet is the same in India as in sub-Saharan Africa. Even at its current rate of growth, India would not catch up with Africa’s current average until 2025. “I could go on,” he told the audience.

Mr. Subramanian said his point was this: “Two vastly different Indias cannot coexist peacefully as a democracy for long.” Everything relating to public health, education, and other “soft” areas falls within the purview of state governments. The winds of change have not yet reached these sectors, not because of lack of awareness but because of a lack of will arising from local political compulsions. The culture of corruption in state and local governance means that, as Rajiv Gandhi had not so jocularly estimated, only 15 percent of the funds earmarked for development actually reach their intended beneficiary.

Although every party to hold power has promised to reach out to the poor that comprise three-fourths of India’s population, there has been no concerted, meaningful effort by the central or the state governments to change this picture. The unspoken presumption has been that all boats would be lifted according to “the trickle-down theory,” but the efficacy of this “strategy” has not become evident—on the contrary. “In an era when information is easily transmitted to the remotest area, and awareness levels have grown, this contrast” between rich and poor, Mr. Subramanian warned, “is not sustainable for long.”

But many state governments, which clearly would have to drive the next series of steps, are now reorienting their approach to rural development strategy.

With two-thirds of the population drawing their livelihood from agriculture, rapid agricultural growth remains the key to poverty alleviation. In the 1950s and 1960s, he recalled, few observers gave India any chance of becoming self-sufficient in agriculture. Indeed, the Club of Rome called the country a “basket case.” The Green Revolution proved the pundits wrong. Though the work was driven locally, led by such people as C. Subramanian and M. S. Swaminathan, there was seminal technical assistance from the United States, and through the World Bank’s intervention.

Cause for concern of late, however, is the deceleration in both production and factor productivity growth recorded in some of the major irrigated production systems, and many areas still do not have access to seasonal irrigation. Although public research and extension programs have played a major role in bringing about the Green Revolution, old methods relying on government servants to transfer technology clearly have severe limitations. The old extension systems are no longer relevant, and no effective new system is yet in place. The state agricultural universities and rural engineering colleges that were designed to support the agrarian sector are hopelessly out of date. New methods, practices, and techniques of delivering technology assistance via the private sector and voluntary agencies are urgently needed. A number of states are already working on these areas, with experiments under way.

Strong Indo–U.S. collaboration, if appropriately designed, could clearly foster a Second Green Revolution, in Mr. Subramanian’s judgment. Strong commitment at the state level in India would also be necessary, however.

Until three years before, when Monsanto had introduced Bt cotton on 45,000 hectares, that variety had been unknown in India. Now Bt cotton is sown on 1.2 million hectares, accounting for 15 percent of the country’s cotton cultivation, and it is expected to account for as much as 50 percent within two to three years. It is imperative to acknowledge, however, that both the pricing policies for Bt cotton and its environmental impact are the subject of “furious” debate in India. The astonishing support enjoyed by the new cotton varieties should be seen side by side with the fact that over 500 farmers commit suicide every year in each of the cotton-growing states. “This, of course, also relates to other aspects of rural reforms,” he said, “like ushering in proper lending policies coupled with crop insurance systems.”

So, there is a major and urgent potential in India for practical and meaningful reform. Although the main effort has to be made within the country, assistance of a critical nature—technical and technological—could be provided by appropriate U.S. agencies. America’s principal gain from the first Green Revolution, which took place during the Cold War, related to the advancement of its geopolitical interests: entry into the Indian political, official, academic, and media zones, which had over time yielded benefit to the United States. With India’s vast rural market potential, partnership in the agricultural sector today can yield rich economic dividends for all.

Interventions in that sector have to be carried out with caution, however. Contract farming is still a bad word in many rural circles, owing to local political sensibilities. “Similarly,” Mr. Subramanian said, “it would be naïve to think that the mere entry of large retail produce-marketing chains from abroad would automatically bring joy to India’s rural areas.” Severe physical infrastructure bottlenecks have to be addressed before the entry of large corporations could add significant value through improving products or generating employment. There is no magic formula in such things.

Among the most pressing requirements for rural development are those found in the fields of energy and education, while those in the field of public health are likewise enormous. Power generation—and especially transmission and distribution to rural areas—is a realm in which the United States and other countries could clearly play an important role. Solar energy is another field offering potential. Opportunity is also ripe in rural India in computer learning, particularly at the lower levels, as new and improved systems for delivering primary and secondary education are of high priority. Significant experiments, some receiving technical and financial support from the United States, are already in progress.

Higher education requires urgent attention as well. Of the more than 500 engineering schools and 600 management institutes in India, only the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and the Indian Institutes of Management are world class, while the rest—a majority—were greatly in need of improvement. According to the assessment by Sam Pitroda, a noted futurologist, India’s requirement for high-quality institutions of higher learning in the coming decade stands at around 200. Most of such institutions were in the purview of state governments, many of which support the upgrading of existing institutions and the initiation of greenfield projects. This is clearly an area offering mutual benefit to India and the United States through the interchange of faculty at all levels.

Prerequisite for the successful implantation of the desired new processes, Mr. Subramanian declared, would be both a major drive to eradicate corruption at all levels and assurance of significant judicial recourse. “No doubt, India has an extremely well-developed and mature judicial structure,” he commented, “but ‘justice delayed is justice denied’ is not currently the guiding principle.”

The week before the conference, Mr. Subramanian had passed a brief holiday at a remote Himalayan village with a total population of about 1,000 living in 10 or so hamlets. In the central marketplace, international telephony and Internet were available and working well. There was even a tiny computer school with all of two computers teaching C++ and graphics. In fact, a high-speed multipurpose underground coaxial cable was being laid in that remote mountain area during his stay. However, while a few new service-sector jobs had been created, there had been no significant job creation in the diversified agrarian sector.

This small hamlet, in Mr. Subramanian’s view, represents the opportunity and the challenge facing India. “The winds of change have come and can no more be resisted,” he said. “Changes of one sort or the other will, willy-nilly,

take place.” In the absence of rapid economic development in India’s rural areas, renewed questioning of the democratic process would take place, a fact well known to the nation’s political decision makers. Therefore, the opportunity for rapid development was not to be missed.

The leadership at the state level has not only to recognize this, but to act. It is imperative to introduce new players, including the private sector and voluntary agencies, which could take on major responsibilities under appropriate safeguards. The bright side was that significant groundwork has already been laid and the remaining work could be accomplished with relative ease in a relatively short time. “All it needs,” Mr. Subramanian concluded, “is a small dose of political will driven by the poor and uneducated Indian.”

INDIA’S KNOWLEDGE ECONOMY IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT

Carl J. Dahlman

Georgetown University

Observing that much was at stake in the day’s discussions, as they concerned two very large and important countries whose further collaboration would be of mutual benefit, Dr. Dahlman called it an honor and a pleasure to participate. He advised the audience that he had so many slides to present that he would go through a number of them quite quickly, emphasizing the key points.

He began by positing that the world was in the middle of what could be called a knowledge revolution. Much new technology was being created, some of it so rapidly that it was very important for countries to develop effective strategies to deal with it. In the case of India, with its “tremendous potential,” this was particularly applicable.

To situate India on the global stage, Dr. Dahlman noted that it is home to 17 percent of the world’s population and has the eleventh largest economy as measured by nominal exchange rates but the fourth largest in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP). Substituting PPP for nominal exchange rates as the yardstick causes India’s share of world GDP to rise from 2 percent to 5.6 percent and thus reveals it as much larger than it might seem. India’s economy is still relatively closed, however, accounting for only 1 percent of world trade, and it faces strong competition from other countries, China in particular.

Comparing innovation indicators for India and China, he stated that the latter has integrated much more rapidly into the global market: Trade in manufactures accounts for 51.3 percent of China’s GDP in 2004 against 13.5 percent of India’s, a “very stark” difference. Similarly, 27.1 percent of China’s manufactured exports fall into the high-tech category, with India’s corresponding figure reaching only 4.8 percent.

Other indicators point in the same direction. China has more than seven times India’s foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP—5 percent vs.

0.7 percent—and a like margin, 810,525 to 111,528, in number of researchers engaged in R&D in 2002. Additionally, China is acquiring $2.75 worth of technology through formal transfer for each member of its population versus India’s 40 cents per person, said Dr. Dahlman. And China spends 1.4 percent of GDP on research and development, whereas India’s share remains at around 0.8 percent. Finally, China is producing about twice the number of scientific and technological journal articles as India, 16.5 vs. 10.73 per million population in 2001, and it was granted 597 U.S. patents in 2004 to India’s 374.

In producing India and the Knowledge Economy for the World Bank, Dr. Dahlman and his coauthor developed a method for assessing how national economies are faring in this new environment based on four of their components, or “pillars”: economic and institutional regime (EIR), education, information infrastructure, and innovation. A country’s EIR governs its “incentives for the efficient creation, dissemination, and use of existing knowledge,” thereby determining the degree to which its economy can restructure itself to take advantage of new opportunities. Education and skills constitute an extremely important topic and one to which Dr. Dahlman would return. The information infrastructure reduces transaction costs, allowing much to be done far more efficiently, and takes knowledge out to the rural sectors, an issue raised by Mr. Ahluwalia and Mr. Subramanian. However, the main focus of his talk was innovation, which covers not only a country’s domestic R&D, as important as that is, but also—and equally important—the ways in which an economy taps into existing global knowledge: via foreign investment, trade, technology transfer, education abroad, the Internet, and technical publications.

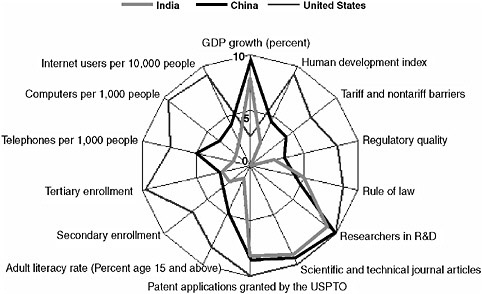

The report’s authors also developed a scoring methodology based on about 20 indicators for each of the four pillars, which he demonstrated by projecting a graphical comparison of India, China, and the United States that used a reduced number of variables (Figure 1).

A country’s place in the rank ordering is indicated by its distance from the circumference of a circle, and, as might have been expected, the United States is closest to the circle in the chart shown. Running through the variables clockwise from the top of the circle, Dr. Dahlman broke them into five categories:

-

Performance—GDP growth and the Human Development Index;

-

Economic and Institutional Regime—tariff and nontariff barriers (which he designated a measure of competition), regulatory quality, and the rule of law;

-

Innovation—researchers in R&D, scientific and technical journal articles, and patent applications granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office;

-

Education—adult literacy rate, secondary enrollment rate, and tertiary enrollment rate;

-

Information Infrastructure—fixed and mobile telephone lines per 1,000 people, computers per 1,000 people, and Internet users per 10,000 people.

FIGURE 1 Comparison of China, India, and the United States.

SOURCE: World Bank Institute, KAM 2006, <http://www.worldbank.org/kam>.

A similar chart depicting the status of this “very serious competition” 25 years before, he said, would have shown India ahead of China in just about every variable, whereas China has now surpassed India in everything but democracy and some aspects of the rule of law.

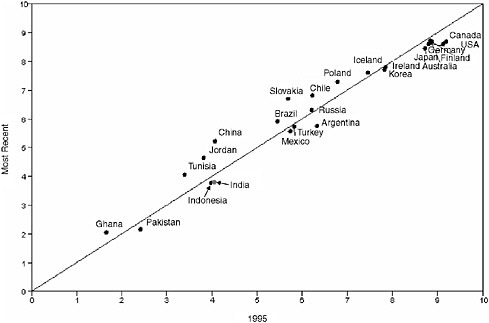

He then projected a graph representing spatially the relative positions of numerous countries in the global knowledge economy (Figure 2).

Plotted according to the horizontal axis was a country’s 1995 position on all the indicators used in the circular chart in Figure 1 minus GDP growth and the Human Development Index; the vertical axis represents its position in 2003– 2004. Position along the diagonal indicated level of development, with the more developed countries situated in the upper-right quadrant, the developing countries toward the middle or in the lower left; India was to be found in the sixth decile. Position relative to the diagonal indicated whether a country’s performance had been better in 1995 or in 2003–2004, with those whose performance had improved rising above the line and those whose performance had deteriorated falling below it. India has fallen back a little, which he said should probably be seen as cause for concern. The main reasons for its decline are related to two of the four “pillars,” EIR and education; when it came to information infrastructure and innovation, India had shown improvement.

This was not to deny that India has registered tremendous accomplishments over the previous two decades, as Mr. Ahluwalia had outlined. The increase in its

FIGURE 2 India in the global knowledge economy.

SOURCE: World Bank Institute, KAM 2006, <http://www.worldbank.org/kam>.

annual average rate of GDP growth—from 6 percent over the 1990s to 6.2 percent from 2000 to 2004 and then 8 percent over the previous three years—is extremely impressive. Moreover, the country has potential for continued acceleration, which in any case is needed to provide opportunities for its fast-growing population and even faster-growing workforce.

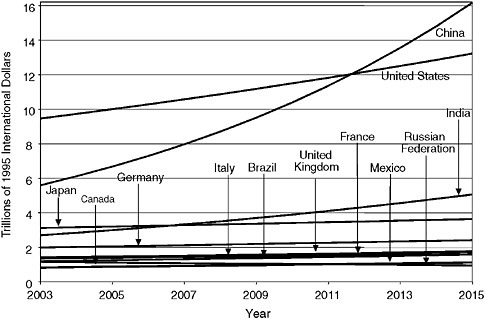

Dr. Dahlman showed a graph (Figure 3) with projections of a dozen major economies’ real per capita GDP growth between 2004 and 2015 in terms of purchasing power parity; these projections were based on the economies’ records of growth over the previous decade.

Plotted according to the vertical axis was GDP in trillions of dollars, with the horizontal access representing time. The chart shows China surpassing the United States by around 2013, while India, already the world’s fourth-largest economy in PPP, is to move past Japan into third place by around 2008. The actual and projected speed of growth of China and India, about three times the world average, is evidence that both economies will become increasingly powerful. For this reason, it is extremely important to keep track of what India is doing, but it also bore remembering that India faces significant competition, particularly from China.

He then recited India’s many fundamental strengths: its very large domestic market, young and growing population, critical mass of educated people, very strong R&D infrastructure, and strong science and engineering capabilities cen-

FIGURE 3 Real GDP projections for 2004–2015.

SOURCE: Projections based on data in the WDI database. World Bank, World Development Indicators 2006, Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 2006.

tered in areas such as chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and software. In addition, India:

-

is becoming the world center for many digital services, a location where “anything that can be offshored” can be done very cost-effectively;

-

is becoming a center for contract innovation for multinational companies, which have established around 400 R&D centers in India to tap its most valuable human resource, its scientists and engineers;

-

enjoys a network based in the worldwide Indian diaspora, strongly represented in the United States, which could prove an excellent source of everything from information and advice to access to markets, technology, and financing as India’s activities increased in sophistication;

-

boasts very deep financial markets, far better than China’s; and

-

is beginning to strengthen its export orientation and to seek strategic alliances.

As for the challenges India faced, Dr. Dahlman said that its very large population—nearly 1.1 billion at present and estimated to grow at an annual rate of 1.4 percent in the period 2004–2020—needs to be “skilled up.” India’s adult population averages 4.8 years of schooling, and its illiteracy rates are 52 percent

for women and 27 percent for men. This very low average level of educational attainment is India’s “biggest Achilles heel” in a world economy where the capacity to absorb and use modern knowledge is so important. China, beginning at a lower level 15 years before, has improved its average education level to eight years, whereas for India this remains a gigantic challenge. Other challenges stem from the fact that India’s economy is overregulated, that it has very poor physical infrastructure, and that it is competing in a very fast-paced, global environment where speed is of the essence.

Dr. Dahlman acknowledged Mr. Subramanian’s contention that there are two Indias: the high-tech India with which many abroad were familiar and that many in the audience represented, and a very poor India. “It’s an extreme dual economy,” he said, “and it is very important to see how we can leverage traditional knowledge and modern knowledge to address the needs of a very large population that is still far behind.” For, at about $620, India’s per capita income remains low.

Nonetheless, India now has a very special window of opportunity during which it could undertake key reforms and leverage its strengths to improve its competitiveness and the well-being of its people. However, even if all the critical ingredients were present, the country has to marshal them well, and time is of the essence. Policy choices would matter: Dr. Dahlman and his World Bank coauthor had made four projections of India’s per capita income through 2020, assuming a constant rate of investment but varying the level of total factor productivity (TFP) growth. They discovered that TFP could make a difference of over 50 percent in per capita income within 10 years. In what might serve as a guide for Indian decision makers, he offered what he called “key areas for action,” organized according to the four pillars of the knowledge economy cited in the report.

Improving the Economic and Institutional Regime

Dr. Dahlman called this step a fundamental one in that it would set the entire context for change. This involves:

-

reducing bureaucracy for the entry and exit of firms;

-

upgrading physical infrastructure, with a focus on power reliability and the efficiency of roads, seaports, and airports;

-

easing restrictions on the hiring and firing of workers;

-

reducing tariff and nontariff barriers, because the Indian economy remains among the world’s most closed, whereas China, having reduced nontariff barriers since joining the World Trade Organization, has become globally very integrated in pure trade structure;

-

encouraging more foreign direct investment and increasing linkages with the rest of the economy;

-

strengthening intellectual property rights and their enforcement; and

-

improving governance and using information and communication technology to improve transparency, something in which India was making considerable progress, although more remains to be done.

Strengthening Education

This would eliminate a basic constraint on India’s advancement. The country provides a small elite with excellent education, but it has quality problems, even in higher education, outside the Indian Institutes of Technology and Science. Important measures would include:

-

expanding the quality of primary and secondary education;

-

raising both the quality of higher education and the number of teachers, the latter being held down by regulatory obstacles even though salaries were beginning to go up very rapidly;

-

embracing the contribution of private providers of education and training by lowering bureaucratic hurdles, among which is an accreditation system that has frustrated many large private universities;

-

developing partnerships between academia and industry to increase the universities’ awareness of the skills required to create the knowledge workers necessary for economic progress;

-

using information and communications technologies to meet the double goal of expanding access to education and improving its quality—which would involve little more than realizing the tremendous potential India has, given its lead in the sector, to reach out to its very large population; and

-

investing in flexible, cost-effective job training programs that can adapt quickly to new skill demands. With the half-life of knowledge growing ever shorter, a massive lifelong learning system allowing those who had left the formal education sector to upgrade their skills was critical. High-tech firms in India, one-third of whose employees are getting more education at any given time, are leading the way, but their efforts have to be expanded in the interest of increased competitiveness.

Leveraging Information and Communications Technologies (ICT)

This step begins with boosting ICT penetration throughout the country, which would require:

-

resolving some regulatory issues, as well as lowering some import costs, the latter by reducing or rationalizing tariffs on hardware and software;

-

massively enhancing ICT literacy, perhaps through programs such as those South Korea had undertaken to build skills enabling its people to use the Internet and other information and communication technologies;

-

exploiting ICT as a competitive tool by using it to increase the efficiency of production and marketing through enhancing supply-chain management and logistics, as well as to improve the delivery of government services—a promising area because India has firms capable of producing important innovations;

-

moving up the value chain in information technology; and

-

providing suitable incentives to promote information-technology applications for the domestic economy, including local language content and applications.

Strengthening Innovation

The “pillar” he had saved for last was the one Dr. Dahlman most wanted to emphasize. He pinpointed areas in which India should make a greater effort:

-

Tapping global knowledge: Its current low share of total world spending on R&D—less than 1 percent or, in PPP terms, about 2.5 percent—indicates that India needs to tap more effectively into the knowledge available beyond its borders. China, in contrast, is doing this very well by bringing in foreign investment, a source not only of capital and capital goods but also of management skills, technology, and access to markets.

-

Attracting foreign direct investment: As indicated, India has a long way to go here despite its liberalization, as many sectors remain closed. Furthermore, many foreign investors are being discouraged by the country’s cumbersome bureaucratic structures, corruption, and poor physical infrastructure. It is because of the constraints involved in the physical movement of products in and out that the country’s biggest growth has been in products and services that can be transported digitally.

-

Making use of its diaspora: Taiwan, Korea, and China have developed effective networks to take advantage of the expertise, skills, and market information of its nationals living outside the country. India is just beginning to do the same, and, Dr. Dahlman observed, many in his audience would likely be able to increase their contribution to its progress.

-

Improving the efficiency of public R&D: India’s total R&D spending comes to only 0.8 percent of GDP, of which around 70 percent is in the government sector. In turn, around 70 percent of that goes to big, mission-oriented programs in defense, oceans, and space, leaving projects more oriented toward the basic needs of the economy—in agriculture, industry, and health—with quite a small share. Dr. Dahlman raised the possibility of redeploying resources to those areas, as well as of increasing the efficiency with which resources were used. Praising Dr. Mashelkar for having done “a remarkable job” in changing the incentive structure of the CSIR laboratories to orient them more toward such needs, he suggested that Dr. Mashelkar’s approach be generalized so that it reached more of the public infrastructure. Also important was moni-

-

toring how effectively resources are used, and once monitoring systems have been improved, looking at the government’s share of R&D spending would be critical.

-

Motivating private R&D investment: The private sector accounts for only 23 percent of India’s total R&D spending, about one-third the level of traditionally industrialized countries. In China, the corresponding figure has reached 65 percent. And, much of this R&D is being done by foreign multinationals, which are performing R&D at 400 labs located in India, proof of the presence in India of a critical mass of scientists and engineers. Why are domestic firms not doing more? Thought should be given to the kinds of programs that might be put into place to encourage them.

-

Shoring up university–industry programs: Matching grants might be one way of fostering interaction between the public and productive sectors.

-

Developing supporting institutions: Dr. Dahlman named as very important to a competitive economy, and thus worthy of support, science and technology parks and incubators; early-stage financing and venture capital; and metrology, standards, and quality control.

-

Enforcing intellectual property rights: Taking steps to protect the fruits of innovation would create confidence among both domestic and foreign researchers.

-

Nurturing grassroots innovation: In need of stronger support was India’s already very extensive program of grassroots innovation, which addressed many of the needs of those left out of the modern economy.

-

Bolstering formal innovation systems: The advanced technology coming out of both public and private innovation systems could help improve broad social and economic conditions, an example being Mr. Ahluwalia’s account of the application of remote-sensing satellites in fishing. “More could be done to find ways of harnessing modern knowledge to meet the very pressing needs of a very large poor population,” Dr. Dahlman said.

-

Broadening science and engineering education: India’s handful of elite institutions, seven IITs plus the Indian Institute of Science, produced only 7,000 science and engineering graduates annually for an economy of more than 1 billion people. This supply shortage needed urgent attention.

Dr. Dahlman concluded by addressing what he called the “tremendous” opportunities that existed for U.S.–India cooperation. Increases are to be envisioned for foreign direct investment going in both directions, for trade in goods and services, and for strategic alliances—notably in pharmaceuticals, software, auto parts, and chemicals, but in many other sectors as well. Cooperation in education and training also holds out great promise, particularly for unleashing India’s high human capital potential. Finally, ample occasion will arise for the two countries to collaborate within the framework of international programs in such areas as

energy and environment. There will be great mutual benefit in increased cooperation, he concluded.

MANUFACTURING INNOVATION AS AN ENGINE FOR INDIA’S GROWTH

Surinder Kapur

Sona Group

Expressing appreciation for the invitation to speak and greeting Minister Sibal and Dr. Mashelkar, who were in the audience, Dr. Kapur announced that he would devote his attention less to India’s achievements than to gaps that remained and the ways in which they are being addressed.

Dr. Kapur introduced himself as chairman of the Mission for Innovation in Manufacturing of the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). CII is a 110-year-old body that represents over 5,000 members organizations; it is, he said, truly the voice of Indian industry. Earlier in 2006, CII established the Innovation in Manufacturing Mission in the belief that it would fall to manufacturing to create the employment required for India’s further economic growth. With India famous the world over for information technology (IT) and IT-enabled services, few recognize that manufactures account for 75 percent of the country’s exports even though the sector represents only 20 percent of its GDP. Because of the manufacturing sector’s role in providing jobs, examining it closely to see how its performance might be improved is vital.

Dr. Kapur noted with contentment that, only days before, IBM had announced a commitment to invest $4 billion in India. Similarly, General Electric had announced its intention to increase its Indian revenue from $1 billion to $8 billion. “India is, in my view, rocking,” he exclaimed. “I think there are great opportunities.”

Beginning his discussion of innovation, Dr. Kapur recalled a statement by S. Ramadorai of Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), whom he described as India’s leading CEO. Ramadorai had said of TCS’s IT-enabled services: “Cost helped us get a foot in the door, quality opened it a little bit more, and now we need innovation to open it all the way.”

CII recognizes, according to Dr. Kapur, that the people-cost arbitrage upon which India has been relying can keep it competitive in the international environment only in the short term. While contract manufacturing currently provides some growth, India needs to reposition itself from low-cost manufacturer and service provider to creative product developer. The Mission for Innovation in Manufacturing is CII’s contribution to this effort.

The mission’s objective is to serve as a facilitator to help 100 Indian companies develop as leaders in innovation and product development over the next three

years. Although this target might not seem very ambitious, CII believes, he said, that these leader companies can create a much-needed ripple effect throughout the country. To help promote the concept of innovation and its associated processes among Indian manufacturers, the organization has proposed to open institutional framework cooperation with such global authorities on innovation processes as Clayton Christensen of Harvard University, Deming Prize winner Shoji Shiba, and Patrick Whitney, director of the Institute of Design at Chicago’s Illinois Institute of Technology. It is also partnering with India’s own National Manufacturing Competitiveness Council (NMCC), formed by the prime minister in 2005 to develop a strategy for enhancing the country’s manufacturing.

CII’s main goal is to catalyze the desired transformation through changing the attitudes of those at the top of manufacturing companies. To find the 100 companies that will emerge as its leaders, the mission is identifying 500 companies with which to begin working. These firms would be introduced to the mission’s roadmap and have their processes benchmarked to help them adopt innovation as their strategy for growth.

As evidence of the prevalence of advanced skills’ in India, Dr. Kapur posted a list of familiar names in U.S. research that are operating R&D centers in India: Bell Labs, Cognizant Technologies, Enercon, Exxon, GE Industrial Systems, GE Medical Systems, IBM, Intel, Lucent, Microsoft, Motorola, National Instruments, Oracle, SeaGate, Texas Instruments, and Xytel. “We believe there is a lot of culture that Indian manufacturing companies need to take advantage of,” he observed.

To demonstrate that innovation is indeed appropriate as the next phase in the country’s development, he provided an outline of the quality movement in which CII has been engaged for decades. Beginning in the 1960s, the organization trained manufacturers in the same process control of associated with Edwards Deming and that had led Japanese manufacturers to such great heights. Practices associated with it—among them gap analysis, corrective countermeasures, and preventive countermeasures—are now in use throughout the world.

From teaching process control, CII had gone on to imparting the tools for continuous improvement. He stated proudly that a strong culture of continuous improvement is developing within Indian manufacturing companies. Not long before, Dr. Kapur had the privilege, as an NMCC member, of presenting India’s prime minister with two CD-ROMs on which were recorded 1,000 kaizens, or improvements, accomplished by Indian companies. He was currently in the process of putting together 100,000 kaizens for the prime minister to deliver to the nation as a way of emphasizing that the CII’s unique method of teaching improvement represented knowledge that belonged to the nation rather than being contained in one particular organization.

Behind CII’s claim of uniqueness lies the fact that India is the first country in the world to have used clustering in pursuit of quality. Formed into 32 clusters were some 270 noncompeting companies too small to afford the high-cost con-

sultants that Dr. Kapur called “really necessary” to learning quality-improvement methods and that the CII itself invited from the United States, Japan, or Europe. He characterized the attitude within the clusters as “one of give and take: ‘I learn from you and you learn from me so that we don’t have to relearn the same things over and over again.’” Clustering had turned into movement that was upgrading quality across India, not only in advanced manufacturing but also in the leather and tea industries.

The CII had also made efforts in policy deployment with management for objectives, a powerful tool for improving results by ensuring that everyone within an organization is in alignment. Dr. Kapur proposed to share the experience of his own firm, the automotive component manufacturer Sona Group, a 16-year-old “boutique global company” with seven plants in India and minority investments in France, Brazil, and the Czech Republic that was posting about $200 million in sales annually. The firm had been able to make “quantum” changes within a short time, which he attributed to its being part of a cluster and to the particular set of tools it employed.

Sona’s focus in its Total Quality Management activities, which began around 1998, is on skill building. In the three years ending in 2003, on a per-million basis the company has reduced its in-house rejections from 23,000 to 876, its supplier rejections from 49,500 to 996, and its customer returns from 1,579 to 112—and it is currently showing far better numbers than it had three years earlier. One illustration is its inventory turnover ratio: After jumping from 7.5 to 32 in the three years ending in 2003, it is running at close to 55, a number that included imported inventory, which in Sona’s case was very high.

Productivity improved over the same three-year period, with gross sales per employee rising from 1.6 million rupees to 5.9 million rupees; currently, the firm was operating at the level of 7 million rupees. Indices of morale are his favorite, Dr. Kapur said, because they demonstrate “the people involvement we were able to generate within three years in this cluster program”: Accidents have been all but eliminated, and absenteeism has dropped from 11.3 to 6 percent over the three years as training on a per-employee per-year basis has grown from 20 hours to 57 hours, with another 12 hours per employee per year added since 2003. Moreover, suggestions per employee per year has climbed from 2 to 20 in the three-year period and subsequently increased to 27.

Breaking through to innovation would be, in CII’s view, the next step for India’s manufacturing industry. In 2004, it established a new cluster under the guidance of Professor Shiba, who came every three months to spend three weeks working with all of the CII companies together in what was termed a “learning community.” Dr. Kapur outlined the results that the program’s four original participants have been able to obtain in six months with the use of Professor Shiba’s methodology—which he calls “Swim with the Fish”—for creating an ambidextrous organization and an organizational architecture in which ideas are not killed:

-

TechNova, holder of 85 percent of India’s market for printing plates despite competition from Kodak and others, was able within half a year to create and roll out a new process, PolyJet BT, for wide-format inkjet printer imaging.

-

Sona Koyo, a steering-systems company in Dr. Kapur’s group, focused on skill development and improved productivity on a particular line by 30 percent within 20 days. It was also able to develop a new electronic power-steering product for the agricultural sector whose implementation it was currently discussing with a number of U.S. companies.

-

UCAL, which manufactures fuel injection equipment in the south of India, developed a concept of “factories within the factory” in which even production workers deal with the customer. It currently had four factories within its main plant.

-

Brakes India Foundry scored a breakthrough in environmental management, becoming a zero-discharge company—and, in the process, bringing a 4 percent saving down to its bottom line.

As a result of these innovation experiences, the four companies were themselves expanding, and more and more companies are signing up to work with Professor Shiba through CII’s program.

There were, in fact, numerous signs that India is approaching world-class status in manufacturing as it prepares to ramp up job creation in the sector. Among them, it boasts (at last count) 16 Deming Award winners, 95 Total Productive Maintenance Awards from the Japan Institute of Plant Maintenance, and a Japan Gold Medal. Although, according to Dr. Kapur, the country is “in a great situation” demographically, poised to become the world’s youngest nation over the next decade, it needs to accommodate between 8 million and 10 million new job seekers every year. Moreover, he acknowledged, its manufacturing and innovation strategy, geared of necessity to the goal of employment generation, faces a number of challenges. At the same time that India expands production capacity, both through foreign direct investment and domestic companies’ enlarging their manufacturing base, it is also saddled with archaic labor laws that could not be changed overnight. These labor laws, pending reform, might prove an obstacle to cooperation with U.S. institutions.

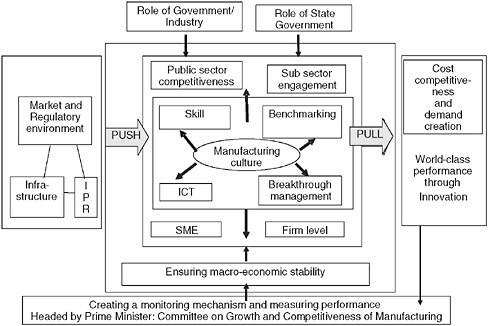

For this reason, the CII was very pleased at both the formation of the National Manufacturing Competitiveness Council and its development of a strategy for increasing manufacturing’s share of GDP to 25 percent from the current 17 percent. Posting a schematic representation of the strategy (Figure 4), he called attention to the fact that the prime minister was personally heading a mechanism for monitoring and measuring performance, the Committee on Growth and Competitiveness of Manufacturing. This was significant not only in demonstrating high-level commitment but also in making certain that, in cases where an intervention by the prime minister’s office was required, it would cut across the bureaucracy from ministry to ministry. Because India needs to create demand

FIGURE 4 NMCC’s manufacturing strategy

through cost competitiveness and to achieve world-class performance through innovation, both the national and the state governments have an important role to play: making the changes that support the environment required. “I’m certain that the manufacturing culture which is at the core of this will come about with the programs that we have put together and the strategies that the National Manufacturing Competitiveness Council has developed,” he declared.

CII’s contribution to this endeavor is to mount an awareness campaign to be kicked off by a visit to India of Christensen, Whitney, and others the following month. Dr. Kapur appealed to the audience for its support at a moment when Indian companies need training in the tools and techniques of innovation, since innovation, he observed, “doesn’t just happen.” In its initial year, the CII’s Innovation Mission Plan would target 10 to 20 companies in each of five focus sectors: machine tools, automobiles and auto components, electrical equipment, chemicals, and leather. A number of skill-building tools would be employed in training the companies: Christensen’s Disruptive Technologies, concept engineering, TRIZ, the Strategy Canvas as put forward in Blue Ocean Strategy, Whitney’s technique for creating concepts, and breakthrough management techniques.

CII plans to continue forming high-tech clusters, in view of their effectiveness to date, and to bundle its programs to work systematically as part of a comprehensive approach. Coming in for particular attention would be small

and mid-sized enterprises (SMEs), which, since they constitute “the real base of manufacturing,” are needed to contribute to the sector’s growth. CII, he said, is in the final stages of setting up an institute in India that, with the participation of Professor Christensen, would work with its SMEs; because small firms could seldom afford such prominent consultants, thought was being given to devising e-learning tools to assist them. “These learning communities are really the ones that are going to diffuse the competencies required for the country,” Dr. Kapur said.

Noting that there were various kinds of cooperation that the CII might forge with institutions in the United States, Dr. Kapur expressed particular regard for U.S. institutions of higher learning: “I am so glad that so many people from academia are here,” he said, “because that is really what is required.” In light of India’s strong motivation to generate jobs in manufacturing and of the increased attention paid the sector’s problems and opportunities in recent years, he predicted: “We will create winners.”

DISCUSSION

Thanking all three speakers for making rich presentations in such a short time, Dr. Patel remarked that their discussion of innovation had taken place in the larger context of India’s development agenda. Mr. Subramanian’s observation that some farmers were resorting to “the extreme measure of suicide,” as Dr. Patel put it, serves as a reminder of the importance of delivering the results of innovation to all levels of India’s diverse population; he had also mentioned the need to address corruption and judicial reform. Dr. Dahlman had talked about how to implement the agenda for India’s near future in the context of what he had referred to as “two Indias.” And CII’s mission, as related by Dr. Kapur, which would allow the scaling up of manufacturing thanks to the ideas about innovation that he had described, also had a larger relevance for India. So, even though the talks had to a certain degree gone over familiar ground, they had been very interesting and had contained some new ideas.

Dr. Patel, opening the floor to the audience, said that he would take three questions at a time, and then ask members of the panel to address them.

Charles Wessner of the STEP Board complimented Dr. Kapur on his exposition of the importance to India of improving manufacturing, but he sounded a note of caution regarding the speaker’s focus on collaborating with U.S. institutions of higher learning. The involvement of academics in the work of the National Academies, to which they frequently contribute, sometimes poses obstacles to obtaining policy-oriented results. Dr. Patel’s colleagues at the World Bank, suggested Dr. Wessner, have excellent experience in providing practical policy advice.

Dr. Wessner then observed that, although Dr. Kapur had made reference to the importance of SMEs, he had spoken neither about how to encourage them nor about linkages between universities and small business. He noted the treatment

that SMEs receive from the U.S. Council on Competitiveness: That organization speaks a great deal about the importance of small business but focuses most of its recommendations on the corporations and universities that are its main stakeholders. Common to many countries is an attitude that Dr. Wessner summed up thusly: “Small business is important; now let’s talk about big business and universities.” His question was whether India had programs at either the national or state level designed to encourage technology transfer from universities to SMEs or to provide the early-stage financing for entrepreneurs.

Dr. Sinha of Penn State, also addressing Dr. Kapur, noted the existence of a report on manufacturing by the National Academy of Engineering in which the term “customerization” is used.6 This appeared to be the manufacturing-sector equivalent of tailoring products to the needs of individual customers and thus to suggest an economy or a manufacturing industry without mass production. He wished to know whether CII had taken such a concept into account in its manufacturing strategy.

Ajay Kalotra said the company he directed, International Business & Technical Consultants, Inc. (IBTCI), is active in the area of development and therefore serves as a consultant to the World Bank and other institutions. He noted that throughout the world, the biggest challenge is trying to figure out how to work on macroeconomic, microeconomic, and enterprise reforms all at once. Given what India is facing, there is no doubt that these reforms need to be implemented simultaneously, and quickly as well. Although Indians have every right to be proud of what they have achieved, the remaining challenges are such that all the progress CII might make within 100 companies would not amount a drop in the ocean for India, nor would bringing in three professors change the course of its history.

Mr. Kalotra had found two further causes for surprise in Dr. Kapur’s remarks: that CII was addressing manufacturing exclusively when service industries were so important and that clustering was being fostered among noncompeting firms for the purpose of regional economic development rather than among competing firms so that they could combine to take on international markets. Noting that he had been away from India for 25 years after having worked there for 21, he asked Dr. Kapur to provide him guidance in general and, specifically, to tell him whether a way had been found to institute microeconomic reforms in millions of enterprises.

Dr. Kapur stated his full agreement with Mr. Kalotra’s assessment that 100 companies constituted a modest initial step, but he suggested that leadership is the most important element when embarking upon change. IT had, after all, started off in India with only two or three companies. CII believed that creating 100 leader companies, which might in turn have hundreds of suppliers, would get

change under way: that if a few hundred companies were created, thousands more might come about. However, “it would be very pompous of me to say that we’re going to have thousands of companies involved in this change movement overnight,” he remarked, adding: “It’s not going to happen.” Just changing people’s mindset is difficult, and CII, being cognizant of the Indian context, needs to take a very realistic view.

In response to Mr. Kalotra’s question about clustering, Dr. Kapur said that the Indian government has begun sponsoring programs in which rival firms collaborate on precompetitive research. New technologies developed by the companies—with the participation of Indian research institutions and, in some cases, U.S. academics or other outside resources—would result in common intellectual property rights in a generic area. The firms could then find applications on their own and compete at the product level. India’s Core Group of Automotive Research, or CAR, was one such collaborative program. Dr. Kapur added that the clustering program he had referred to is aimed at helping noncompeting companies learn the processes of change rather than at specific industrial applications.

He then turned to Dr. Sinha’s reference to the NAE report regarding “customerization.” Changeover times are extremely important for going from mass customization to one-off production without loss of efficiency. Indian firms are learning, through programs already under way, manufacturing-cycle efficiency needed for success in handling “design of one” or “production of one.”

Turning to Dr. Wessner’s question about SMEs, Dr. Kapur stated that the real challenge was motivating SMEs to do R&D. CII is finding that as companies’ internal processes and managements improve, they begin to move in the direction of doing R&D and being involved in innovation. It was here that the clustering approach comes in. One illustration is CII’s Chennai cluster of six companies in the leather industry, which—undoubtedly to the surprise of many—is a larger exporter than the auto components sector. Dr. Kapur termed the benefits beginning to accrue to these six companies, which had agreed to work together in the cluster even though they were competitors, to be “just amazing.” As he had said in conversation with Dr. Patel earlier, where help from the World Bank and similar institutions was really needed was in funding programs for SMEs; establishing such programs would represent a major step forward.

Before taking a final question, Dr. Patel wished to note that the question Mr. Kalotra had raised regarding the role and timing of macroeconomic, microeconomic, and enterprise reforms was not susceptible of a clear-cut answer. Even if a discussion could be focused on one specific subject, such as the day’s theme of innovation, it was always the reality on the ground that many things had to take place in tandem and at the same time. Deputy Chairman Alhuwalia, who had dealt with this issue from 1991 onward, might have had a better answer, allowed Dr. Patel. His own view, however, was that India’s macroeconomic reform program had to continue and that it had to take into account all the issues regarding the overall economic environment in India so far raised at the symposium.

He then listed a number of binding constraints that had been mentioned:

-

the low level of education, which has implications for what macro policy needs to do to create the kind of skilled labor and skilled human resources that India needs to grow at 10 percent per year;

-

the challenge of achieving results in the context of the “two Indias,” a phenomenon that has macroeconomic implications because, if it were not addressed, the people or regions or states left behind would become a source of instability.

-

the lack of infrastructure, which refers not simply to building more roads but to creating a macroeconomic framework that would allow investment from the private sector to fill the strategic infrastructural gaps that existed.

The answer to the question, therefore, was that owing to the complexity of actual conditions, India’s macroeconomic managers had to continuously create the kind of space and environment that would allow the scale-up of the programs that had been described. He then asked for one more question.

Sujai Shivakumar of the STEP Board, referring to Dr. Dahlman’s statement that the level of private-sector R&D in India was relatively low, asked whether Dr. Kapur had an explanation for this and whether anything was being done about it. In addition, he asked Mr. Subramanian whether there were lessons to be learned from those among the Indian states that appeared to be doing better than the others.

Mr. Subramanian acknowledged that some states were indeed doing better than others, ascribing this in part to the history of the Mogul and British periods and specifically mentioning the contrasting development of the coastal and interior regions during the latter. Additionally, many of India’s southern states had far better systems of basic education and nutrition, a fact related to these states’ response to public developmental issues under democracy. But this was also linked to broad macroeconomic development and came back to fundamentals: Without concentration on public health and primary education, nothing else will flow. Playing a role as well was the fact that, while some states are still absorbed with issues of caste and other local concerns, others have moved into developmental issues on a slightly higher plane. Dr. Shivakumar’s question was an important one, he said, because most of the themes affecting the average citizen are within the authority of the states, with the central government doing only so much to direct traffic in those areas.

Dr. Kapur, in response to Dr. Shivakumar’s inquiry about research spending by the private sector, noted that R&D is a recent phenomenon in India. Before reform took hold in 1991, restrictions on investment had been significant. Even today, most manufacturers there are involved in one form or another of contract manufacturing and thus have no real need to do R&D. In view of this, current R&D spending could be considered fairly good. Secondly, a company such as

Sona, which is in the metal-forming business, does all its design, analytical work, and simulation in virtual space, where costs were very low. He therefore expressed doubt that India’s private sector needs to spend a much higher percentage of its revenue on R&D.

However, the real issue, he stressed, is that R&D is required by companies creating their own products and processes, their own intellectual property, rather than by contract manufacturers. He noted that Swati Piramal was to speak later in the day about the R&D efforts that Nicholas Piramal India Limited is making because such efforts are now required of pharmaceutical companies whereas they had not been in the past. A change was taking place, everyone had begun doing R&D, and this would be reflected in spending growth.

Dr. Kapur then turned to the issue of skill development, which, he predicted, would impel great movement in public–private partnerships. India possesses a phenomenal physical infrastructure in its Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs), but owing to a lack of state funding they have unfortunately been allowed to decay over the years. A shift is under way, however: The previous year, India’s Finance Minister challenged industry to create partnerships with ITIs, and many firms are beginning to work with their local institutes. His own state, Haryana, has relinquished exclusive ownership of its ITIs, giving industry a much larger role in them. The private sector will assume increasing responsibility for skill development because, as Dr. Kapur put it, “this is our requirement and we need to do it for ourselves.”

Dr. Dahlman said that if India could leverage the resources it had within its own national economy, it would make tremendous progress. Critical to this was Indo–U.S. collaboration, which has the potential to become “a very nice, symbiotic strategic alliance.” This prospect, he stated, lent excitement to the day’s meeting, and it would, he hoped, provide the impetus for nailing down specific opportunities for partnership.

Dr. Patel concluded by thanking the presenters and questioners alike for a very interesting session.