5

Planning for and Regulating Wind-Energy Development

The purpose of this chapter is to describe the current status of planning and regulation for wind energy in the United States, with an emphasis on the Mid-Atlantic Highlands, and then critique current efforts with an eye to where they might be improved. To accomplish this purpose, we reviewed guidelines intended to direct planning and regulation of wind-energy development as well as regulatory frameworks in use at varying geographic scales. To enhance our interpretation of wind-energy planning and regulation in the United States, we drew on the experiences of other countries with longer histories of wind-energy development and different traditions of land-use planning and development regulation. We focused on onshore wind energy, although many elements of planning and regulation that influence onshore wind-energy developments apply to offshore installations as well.

As with other human endeavors that engage both private and public resources, wind-energy development is influenced by an interconnected, but not necessarily well-integrated, suite of policy, planning, and regulatory tools. “Policy” can be broadly defined to encompass a variety of goals, tools, and practices—some codified through laws; some less formally specified. (For a discussion of traditional and new policy tools, see, e.g., NRC 2002.) Policies encompass, but are not limited to, planning and regulation. Policy tools related to wind energy, including national and regional goals, tax incentives, and subsidies, have been discussed in Chapter 2, so we concentrate on planning and regulation here. “Planning”—whether legally mandated or not—is a process that typically involves establishing goals; assessing resources and constraints, as well as likely future conditions; and

then developing and refining options. “Regulation,” as understood within a legal framework, typically consists of methods and standards to implement laws. Regulation is created and carried out by public agencies charged with this responsibility by law. The scope of agency discretion in establishing and administering regulations depends largely upon whether the law is highly detailed or more general.

The chapter begins with a review of guidelines that have been developed to direct wind-energy planning and/or regulation. Some of these have been promulgated by governmental or non-governmental organizations concerned with limited aspects of wind energy, such as the guidelines for reducing wildlife impacts developed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS 2003). Some are more comprehensive in scope, such as those developed by the National Wind Coordinating Committee (NWCC 2002). We also consider guidelines developed by states to direct wind-energy development toward areas judged most suitable and to assist local governments in carrying out their regulatory responsibilities with respect to wind energy. Then we review regulation of wind-energy development via federal laws, including development on federal lands, in situations where there is a federal nexus by reason of federal funding or permitting, and where there is no such nexus. Next we review regulation of wind-energy development at the state and local levels by concentrating on recurring themes: the locus of regulatory authority (state, local, or a combination thereof); the locus of review for environmental effects; information required for review; public participation in the review; and balancing positive and negative effects of wind-energy development. In these sections we also report on the interaction between planning and regulation, although that interaction is generally less well developed in the United States than in some of the other countries we examined. Then we critique what we have learned about regulation of wind energy by examining some of the tensions in regulation, for example between local and broader-level interests and between flexibility and predictability of regulatory processes. Finally, we present a set of recommendations for improving wind-energy planning and regulation in the United States.

GUIDELINES FOR WIND-ENERGY PLANNING AND REGULATION

In the United States and, notably, in other nations with considerable wind-energy experience, governmental and non-governmental organizations working at various geographic scales have adopted guidelines to help those developing wind-energy projects and those regulating wind-energy development to meet a mix of public and private interests in a complex, and often controversial, technical environment. Here we review U.S. guidelines for different jurisdictional levels (e.g., state, local), for different environ-

mental components (e.g., wildlife), and for the different purposes of guiding planning versus guiding regulatory review. We also draw on the experience of other countries where guidelines for wind-energy development have a longer history.

Some guidelines are for proactive planning of wind-energy development. “Planning” is an ambiguous term, however. Within the context of wind-energy development, it can refer to highly structured processes that carry considerable legal weight and result in identifying certain areas as suitable for wind turbines (as in the Denmark example below). Alternatively, it can refer to loosely structured processes that are largely advisory and result in criteria for evaluating the favorable and unfavorable attributes of prospective sites (as in the Berkshire example below). In addition, planning for wind-energy development may take a broad view of the incremental impacts of multiple wind-energy projects in a region, or it may take a narrow view and focus primarily on a single project. And, geographic scales for planning range from the national to the local level.

Other guidelines focus on regulation. They prescribe for regulatory authorities reviewing wind-energy developments what procedures should be followed, what kinds of information should be examined, and what criteria should be used to make permitting decisions. Many guidelines mingle the two functions of planning and project-specific regulatory review. In practice, planning guidelines that suggest where and how wind-energy development should be done may become criteria for regulatory permitting decisions if projects inconsistent with planning guidelines are rejected.

The United States is in the early stages of learning how to plan for and regulate wind energy. The experiences of other countries, where debates over wind energy have been going on for much longer, can be instructive for bringing U.S. frameworks to maturity. For example, Britain and Australia have dealt with controversies about wind-energy development by working with stakeholder groups, including opponents of wind energy, to develop “Best Practice Guidelines” (BWEA 1994; AusWEA 2002). BWEA (British Wind Energy Association) and AusWEA (Australian Wind Energy Association) were convinced that “they needed to become more transparent and more engaged with the public than any other industry” (Gipe 2003). In Ireland, the Minister of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government released an extensive “Planning Guidelines” document on wind energy in June 2006 (DEHLG 2006). This document advises local authorities on planning for wind energy in order to ensure consistency throughout the country in identifying suitable locations and in reviewing applications for wind-energy projects. Not only are these guidelines prescriptive—that is, they express procedures and approaches that should be taken—but they also are linked to other government policies.

A prescriptive national approach is less likely in the United States, where each state is governed by different laws and policies regarding the regulation of wind-energy projects, but the comprehensive approaches used in other countries could be adopted at the state level. The highly structured approach of Denmark, for example (see Box 5-1), could be informative for states wishing to develop integrated frameworks to plan for and regulate wind-energy development. We note, however, that Denmark is smaller and more homogeneous than many U.S. states, has a much stronger tradition of central planning of land use, and has many wind projects owned by local cooperatives, rather than private developers.

National Wind Coordinating Committee Guidelines

The NWCC was established in 1994 as a collaboration among representatives of wind equipment suppliers and developers, green power marketers, electric utilities, state utility commissions, federal agencies, and environmental organizations. Its permitting handbooks propose guidelines for how wind-energy developments should be reviewed. In 2002, the Siting Subcommittee of the NWCC revised its Permitting of Wind Energy Facilities: A Handbook, originally issued in 1998 (NWCC 2002). Intended for those involved in evaluating wind-energy projects, the handbook describes the five typical phases of permitting processes for energy facilities, including wind turbines and transmission facilities:

-

Pre-Application: This phase occurs before the permit application is filed, during which the developer meets with the permitting agency(ies) and others immediately affected, such as nearby landowners, and local agencies. This phase may be mandatory or voluntary, and it may involve public notice and/or public meetings.

-

Application review: This phase begins when the permit application is filed. Its activities, required documents, and public involvement requirements depend upon the application review process, as does its duration. In some cases, agencies may be required to reach a decision within a specified period.

-

Decision making: In this phase, the lead agency determines not only whether to allow the project but also whether to impose measures constraining the project’s construction, operation, monitoring, and decommissioning. During this phase, public hearings are likely to be required.

-

Administrative appeals and judicial review: Appeals of permit decisions may be made to the decision maker, to the administrative review board, or to the courts.

-

Permit compliance: This phase extends through the project’s life-

-

BOX 5-1

Planning for Wind-Energy Development in Denmark

Until the beginning of the 1990s, the approach in Denmark (like the U.S. approach today) was: “Find yourself a site, and then apply for permission to erect your wind turbine(s)” (DWEA 2004). This laissez-faire approach changed in the early 1990s, when Denmark’s third energy plan—Energy 2000—was put forward. It included the goal of 1,500 MW of installed wind energy by 2005. In 1994, an executive order, the “Wind Turbine Circular,” made cities responsible for planning for wind turbines, including looking for appropriate sites. In 1999, with a new Wind Turbine Circular, the planning responsibility was redirected to county (amt) authorities. These county-level efforts, and corresponding local efforts, target areas considered suitable for wind farms. The original goal of 1,500 MW nationally was met several years before the 2005 deadline.In 2002, the Danish government indicated that further onshore wind-energy development would not be encouraged but that offshore wind-energy development would be allowed. Denmark’s success in installing so much wind-energy capacity has been attributed to numerous factors including (1) the relatively small size of wind projects (1-30 turbines), (2) cooperative ownership of many wind projects with direct benefits to local citizens, and (3) comprehensive planning and review in which localities directly participate (J. Lemming, RISØ, personal communication 2006; Nielsen 2002).

Regulatory Review Within a Planning Context

In Denmark, planning for land-based wind development is linked to the regulatory review process. The centerpiece of the review process is a mandatory environmental impact assessment (EIA) (if a project involves more than three wind turbines or wind turbines over 80 meters in height). The regional planning authority—typically, the county—is responsible for initiating the EIA and ensuring its quality. The EIA is a joint effort of the developer, the developer’s consultants, and the county. The EIA must describe the project and establish that the site is appropriate from a wind resource standpoint.The site is further described, including working areas and roads to be used during construction. Alternative sites must be investigated, as well as the no-build alternative, and the developer must substantiate why the proposed site is preferred.

time. It may include monitoring, inspection, addressing local complaints during the project’s operation, as well as following up on requirements for closure and decommissioning.

These five phases are included in the handbook as descriptions of what typically happens (given a great deal of variation among states), not as recommendations of what should happen. However, the authors of the handbook suggest eight principles that should be followed when structuring a permit review process:

|

The EIA must describe the landscape surrounding the site, with emphasis on anything that may be affected during the construction or operation phases of the project. Protected species of flora and fauna require special consideration, as do birds protected under international agreements. Any adverse effects on water reserves must be noted. If the project is to be located outside areas previously designated for wind farms, conflicts over the use of land (e.g., because of protected species, arable land, scenic resources) must be given special attention. The EIA also should assess the project’s positive environmental impacts (e.g., reduced CO2,NOx, and SO2. Standards have been set for evaluating impacts on the human environment. No turbine may be sited closer to the nearest residence than a distance of four times the height of the turbine.The EIA must address adverse noise and visual impacts, including cumulative impacts from multiple turbines within a radius of 1 to 2 km. The noise level from the wind turbine(s) must be estimated, using a protocol described in the Noise Declaration (a national-level regulation).The EIA must describe how far shadows from the turbines will reach at all times of year, and the layout of the turbines in relation to major landscape features must be described. Possible adverse effects on property values, tourism, and other commercial activities in the vicinity should be described. Prior to preparation of the EIA and the planning documents, the project must be publicized for at least four weeks, with opportunities for private citizens and organizations to submit suggestions and comments.These submissions must be included when preparing the EIA. Following completion of the EIA and the planning documents (or their amendments), this material must be publicized for at least eight weeks, after which a public hearing is held where suggestions or objections are again gathered. Following the final decision on the project, anyone who has submitted objections to the project must receive a written answer to the objections. When the EIA is completed, authorities at the county and local levels formulate amendments to their wind-energy plans, using the EIA as a common point of reference. During the subsequent public comment period, the state can veto the project (this is a national-level decision) but must substantiate why it is exercising its veto power. After public hearings, the plans are presented to county and local political bodies (the county council and the city council). The county council or city council may approve or reject the project.Construction begins only if the project has been approved (Ringkøbing Amt, Møller og Grønborg, and Carl Bro 2002). |

-

Significant public involvement: Including early and meaningful information and opportunities for involvement.

-

An issue-oriented process: One which focuses the decision on issues that can be dealt with “in a factual and logical manner” (NWCC 2002, p. 16).

-

Clear decision criteria: As well as clear specification of factors that must be considered and minimum requirements that must be met.

-

Coordinated permitting process: Including both horizontal coordination among various agencies and vertical coordination between state and local decision makers.

-

Reasonable time frames: In part to provide the developer with known points for providing information, making changes, and receiving a decision.

-

Advance planning: In particular, early communication on the part of the developers and the permitting agencies.

-

Timely administrative and judicial review: Including addressing issues such as who has standing to initiate a review and time limits within which reviews must be initiated.

-

Active compliance monitoring: Including specifying reports that must be submitted and establishing site inspection timetables, non-compliance penalties, a complaint resolution process, etc.

Federal Government Guidelines

Concerns about the effects of wind-energy projects on bird and bat mortality, in combination with federal laws protecting some wildlife species, led the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to provide interim guidelines for evaluating wildlife impacts (technical aspects of which are reviewed in Chapter 3). We know of no other federal-level guidelines addressing the review of wind-energy projects on private land. However, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) reviews all structures 200 feet or taller for compliance with aviation-safety guidelines. There have not been uniform standards until fairly recently (see Box 5-2). Both the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) provide guidance for the review of wind-energy projects on lands under their jurisdictions. These are described below under federal regulatory approaches to wind energy.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Interim Guidelines

On May 13, 2003, the USFWS released “Interim Guidance on Avoiding and Minimizing Wildlife Impacts from Wind Turbines” (USFWS 2003). Adherence to the guidelines is voluntary, as the guidelines note:

. . . the wind industry is rapidly expanding into habitats and regions that have not been well studied. The Service therefore suggests a precautionary approach to site selection and development and will employ this approach in making recommendations and assessing impacts of windenergy developments. We encourage the wind-energy industry to follow these guidelines and, in cooperation with the Service, to conduct scientific research to provide additional information on the impacts of wind-energy development on wildlife. We further encourage the industry to look for opportunities to promote bird and other wildlife conservation when planning wind-energy facilities (e.g., voluntary habitat acquisition or conservation easements) (USFWS 2003, emphasis added).

|

BOX 5-2 Federal Aviation Agency (FAA) Obstruction Lighting Guidelines To determine lighting requirements, each site and obstruction is reviewed by the FAA for particular safety concerns, such as distance from nearby airports. Negative effects of required lighting on night-flying birds and bats, and sometimes also on people near wind-energy projects, have prompted revisions of initial lighting standards for wind turbines. A recent study conducted by the FAA Office of Aviation Research resulted in recommendations for obstruction lighting that considerably reduced earlier lighting guidelines (Patterson 2005). The following chart summarizes the former and current guidelines, though individual site requirements may vary. Source of current guidelines: FAA (2007).

|

The guidelines include recommendations regarding:

-

A two-step site evaluation protocol (first, identify and evaluate reference sites—i.e., high-quality wildlife areas; second, evaluate potential development sites to determine risk to wildlife and rank sites against each other using the highest-ranking reference site as a standard).

-

Site development (e.g., placement and configuration of turbines, development of infrastructure, planning for habitat restoration); and turbine design and operation (USFWS 2003).

The guidelines direct wind-energy development away from concentrations of birds and bats and toward fragmented or degraded habitat (rather than areas of intact and healthy wildlife habitat). The guidelines also address some desirable features of regulatory review processes, such as recommending multiyear, multiseason pre-construction studies of wildlife use at proposed project sites; multiyear, multiseason post-construction studies to monitor wind-project impacts; and involvement of independent wildlife agency specialists in development and implementation of pre- and post-construction studies. The guidelines were circulated to the public with a request for review and the Service recently announced the development of a Federal Advisory Committee Act-compliant collaborative effort to revise the guidelines based on public comment.

State and Regional Guidelines

Several states with wind resources have developed guidelines for siting and/or permitting wind-energy projects. This has been particularly true for states where review occurs at the local level, since the projects may be complex and very different from the kinds of projects most local governing bodies are used to addressing. The NWCC Guidelines (NWCC 2002) appear to have provided a useful template for states, with basic information that can be adapted to the particular needs and conditions of states that have wind potential. Below we describe a few of these to illustrate the types of provisions that state guidelines may include.

Kansas’s wind-energy guidelines were adapted from the NWCC Guidelines and are intended to assist local communities in regulating land use for wind-energy projects. The guidelines recognize landscape features that are important in Kansas. Under “Land Use Guidelines,” (KSREWG 2003, p. 3) native tallgrass prairie landscapes are singled out as having particular value, especially where they remain unfragmented. Cumulative impacts are noted because there is intense interest in wind-energy development in certain areas of the state. Kansas includes guidelines on “Socioeconomic, Public Service and Infrastructure,” as well as on public interaction (KSREWG 2003, p. 6).

South Dakota also adapted NWCC permitting guidelines (SDGFP 2005). In sections concerning “natural and biological resources,” South Dakota’s guidelines call attention to areas of the state that have been identified as potential sites for wind-energy development, but are considered “unique/rare in South Dakota” (SDGFP 2005, p. 1). Developers are urged to use environmental experts to make an early evaluation of the biological setting and to communicate with agency, university, and environmental organizations. They are warned that “if a proposed turbine site has a large

potential for biological conflicts and an alternative site is eventually deemed appropriate, the time and expense of detailed wind resource evaluation work may be lost” (SDGFP 2005, p. 3). In sections on “visual resources,” developers are told to inform stakeholders about what to expect from a wind-energy project, target areas already modified by human activities, and be prepared to make tradeoffs and coordinate planning across jurisdictions and with all stakeholders. Under “socioeconomic, public services, and infrastructure,” developers are admonished not to take advantage of municipalities that lack zoning or permitting processes for wind-energy development.

Wisconsin’s guidelines (WIDNR 2004) focus on natural resource issues with minimal guidance in other areas. The guidelines direct wind-energy development away from wildlife areas, migration corridors, current or proposed major state ecosystem acquisition and restoration projects, state and local parks and recreation areas, active landfills (because they attract birds), wetlands, wooded corridors, major tourist/scenic areas, and airports and landing strips clear zones. USFWS guidelines are cited as models for pre-construction studies, with two years of post-construction monitoring recommended for the first wind-energy projects in a particular area.

In contrast with guidelines focused exclusively on wildlife issues, some guidelines reflect a much more comprehensive approach. As illustrated in the accompanying box (Box 5-3), the wind-energy siting guidelines developed by the Berkshire Regional Planning Commission in Massachusetts are multifaceted and proactive, as is an assessment methodology prepared by the Appalachian Mountain Club for wind energy in the Berkshires (BRPC 2004; Publicover 2004).

Regulatory review processes could possibly use such a method to evaluate proposed wind-energy projects to see if they met a threshold for suitability. Similar procedures have been proposed for other states, such as Virginia, where Boone et al. (2005) proposed a land-classification database for use in screening out sites that are likely to be deemed unsuitable for wind-energy development, such as designated wilderness areas or concentrations of birds or bats.

Guidelines Directed Toward Local Regulation

In some cases, the guidelines that states have developed are intended to serve as models for local ordinances and local-level review processes. The “Michigan Siting Guidelines for Wind Energy Systems” (MIDLEG 2005) is a model zoning ordinance for local governments, although it notes that “the Energy Office, DLEG (Department of Labor and Economic Growth) has no authority to issue regulations related to siting wind energy systems”

|

BOX 5-3 Guidelines for Planning and Regulatory Review of Wind Energy in the Berkshires, Massachusetts Perhaps as a result of interest in wind-energy project development in the Massachusetts Berkshire region, the Berkshire Regional Planning Commission developed “Wind Power Siting Guidelines” (BRPC 2004). Most of these guidelines refer to desired features of application and regulatory review procedures. For example, the guidelines direct that viewshed analyses should be done “with the most accurate elevation data available from the state using a GIS such as ArcGIS Spatial Analyst or 3D Analyst” (BRPC 2004, p.1) and that “important cultural locations, Shakespeare & Company, and Hancock Shaker Village should be located on the map to determine if they will be impacted by the visibility of the turbine development” (pp. 1-2).There are also safety guidelines, such as “Existing homes are not within potential safety impact areas from ice or blade throw or tower failure” (p. 2). The commission also asked the state of Massachusetts to become involved in wind-energy development to provide “state-wide siting guidelines for the development of wind power facilities” (p. 3) and “financial assistance to municipalities with areas conducive to wind-energy development to develop adequate local land use regulations for wind energy facilities” (p. 4).The commission suggested that communities hosting wind-energy projects should require that applicants pay for consultants to assist the municipality in evaluating the possible and negative impacts of a proposed project and in establishing beneficial agreements for municipal revenue generation. Also working in the Berkshires, the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC) developed “A Methodology for Assessing Conflicts Between Windpower Development and Other Land Uses” (Publicover 2004). This document considers various ecological and sociocultural characteristics that make sites appropriate or inappropriate for wind-energy projects, beyond engineering or economic considerations. Beginning with Geographic Information System (GIS) layers identifying wind sites of Class 4 and above, the AMC methodology overlaid known ecological, recreational, and scenic resources onto the wind map. Resource data were assigned “conflict ratings” that included importance of a resource (local, state, federal significance), proximity to the site, and size of the area.These data can be examined with different subjective weightings on ecological and social factors to see how they might affect an overall site suitability rating. A trial application of this method of analysis suggested that certain sites had far fewer conflicts than others, but the authors cautioned that many variables that could be important to siting decisions were not included in the study. |

(MIDLEG 2005, p. 1). Pennsylvania also has produced a model zoning ordinance for local communities (Lycoming County 2005), discussed below in the analysis of state and local regulatory review. Both the Michigan and Pennsylvania models are very basic in their requirements, with little detail about information required or how it will be judged.

REGULATION OF WIND-ENERGY DEVELOPMENT

In this section we move from guidelines for planning and regulating wind-energy development to a review of regulatory frameworks that have been put in place at different jurisdictional levels and for different land ownerships. First, we review federal regulation of wind energy: most narrowly, federal regulation of wind-energy development on federal lands; then federal regulation of wind-energy development that has a federal “nexus” via federal funding or permitting; then, most broadly, federal regulation of wind-energy development regardless of land ownership.

To better understand regulation of wind-energy development, we review regulatory frameworks for a number of states. Because the focus of this document is the Mid-Atlantic Highlands, we include all four states in this region (Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia). These four states vary in the intensity of their review processes, thus giving a picture of the range of regulatory oversight in the United States today. We also review wind-energy regulation for states outside the Mid-Atlantic Highlands, choosing some from northeastern states that share many landscape, social, and wind-energy characteristics with the Mid-Atlantic Highlands, and some from contrasting landscapes.

In reviewing regulatory frameworks at all levels, we emphasize regulations that are likely to be particularly salient for wind-energy projects, and especially regulations that are likely to affect wind development in the Mid-Atlantic Highlands region. We give rather little attention to regulations that apply equally to any type of construction or industrial operation, wind energy or other.

Federal Regulation of Wind Energy

Federal Regulation of Wind-Energy Development on Federal Lands

As of mid-2005, all of the wind-energy facilities erected on federal lands were in the western United States on land managed by the BLM; they included about 500 MW of installed wind-energy capacity under right-of-way authorizations (GAO 2005). At that time, the BLM developed its Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement on Wind Energy Development (BLM 2005a) in order to expedite wind-energy development in response to National Energy Policy recommendations. The Wind Energy Development Program, which is to be implemented on BLM land in 11 western states, establishes policies and best-management practices addressing impacts to natural and cultural resources (BLM 2005b).

As of mid-2006, other federal land management agencies such as the USFS had not developed general policies regarding wind-energy develop-

ment and were reviewing proposals on a case-by-case basis. No windenergy projects currently exist on USFS lands but two were under review as of mid-2006,1 one in southern Vermont in the Green Mountain National Forest and another in Michigan in the Huron Manistee National Forest. National Forests operate under the guidance of Land and Resource Management Plans, which form the basis for review of all proposed actions. Recent updates of Forest Land and Resource Management Plans address wind-energy projects. In most cases a project would require a “special use authorization” (Patton-Mallory 2006). If an application is accepted, the project undergoes National Environmental Policy Act (1969) (NEPA) review (see next section), but the process will vary depending on the agencies and states involved.

Section 388 of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 gave the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Minerals Management Service (MMS) responsibility for reviewing offshore wind-energy development proposals that occur on the outer continental shelf. As of the fall of 2006, the MMS was drafting a programmatic environmental impact statement (EIS) for renewable energies on the outer continental shelf. No offshore wind-energy project was operational or even under construction in the United States at the end of 2006.

Federal Regulation of Wind-Energy Projects with a Federal “Nexus”

Wind-energy developments are subject to the NEPA if they are considered “federal actions” because a federal agency is conducting an activity, permitting it, or providing funds for it. (Another potential federal “nexus” for wind energy—the federal production-tax credit for renewable energy facilities [see Chapter 2]—does not trigger review under the NEPA.) The Council on Environmental Quality has promulgated regulations that include provisions for establishing categorical exclusions from NEPA requirements (NEPA Task Force 2003). Otherwise, the NEPA requires that federal agencies prepare an environmental assessment or, if significant impacts are anticipated, the much more extensive EIS. An EIS must describe the proposed action and provide an analysis of its impacts as well as alternatives to that action, and it must include public involvement in the EIS process. If an EIS is undertaken, socioeconomic impacts must be analyzed as part of the EIS. Otherwise, socioeconomic/cultural impacts of wind-energy projects are given little explicit attention at the federal level. Wind-energy projects on BLM land are under a programmatic EIS, as described above (BLM 2005a).

Federal Regulation of Wind-Energy Development in General

Federal regulation of wind-energy facilities is minimal if the facility does not receive federal funding or require a federal permit; this is the situation for most energy development in the United States. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) regulates the interstate transmission of electricity, oil, and natural gas, but it does not regulate the construction of individual electricity-generation (except for non-federal hydropower), transmission, or distribution facilities (FERC 2005).

Apart from the FAA guidelines, the threat of enforcement of environmental laws protecting birds and bats is the main federal constraint on wind-energy facilities not on federal lands, because—as discussed in Chapter 3—bird and bat fatalities have been observed at a number of existing facilities. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act applies to all migratory birds native to the United States, Canada, and Mexico; this includes many species that use the Mid-Atlantic Highlands, including for migration. The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (16 U.S.C. §§ 668a-d, last amended in 1978) protects two raptor species. Bald eagles nest in isolated parts of the Mid-Atlantic Highlands whereas golden eagles are mainly migrants or winter residents, although a few may nest in the region (Hall 1983). Permits to “take” species protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. §§ 703-712) and to take golden eagles under the Bald and Golden Eagle Act can be issued by the USFWS in very limited circumstances. The Endangered Species Act (ESA) (7 U.S.C. 136; 16 U.S.C. 460 et seq. [1973]), protects species that have been listed as being in imminent danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of their range (endangered) or those that are likely to become endangered without appropriate human intervention (threatened). There are federally listed species from many taxa in the Mid-Atlantic Highlands, some of which may be affected by windenergy projects (Chapter 3). The ESA also protects habitat designated as “critical” to the survival of listed species. Non-critical habitat is protected indirectly in that if habitat destruction would lead to the direct take of an individual of the protected species, destruction of the habitat would be a violation of the ESA. In this situation the species is receiving the protection, not the habitat. Thus, the ESA provisions could affect wind-energy development not only via mortality of birds and bats due to collisions with wind turbines, but also via mortality or habitat loss for endangered or threatened species due to construction and operation of wind-energy facilities. The ESA does allow incidental taking of a protected species (i.e., taking that is incidental to an otherwise legal activity) if a permit has been granted by the USFWS. This provision has been applied to a wind-energy development via incidental take permits that have been approved as part of the Habitat Conservation Plan submitted during the permitting process for the Kaheawa

Pastures Wind Energy Generation Facility on Maui (HIDLNR 2006). The USFWS is responsible for implementation and enforcement of these three laws. Violations are identified in several ways, including receiving citizen complaints and self-reporting by individuals or industry. Although the USFWS investigates the “take” of protected species, the government, as of mid-2005, had not prosecuted industry, including wind-energy companies, for most violations of wildlife laws (GAO 2005).

Like other construction and operation activities, wind-energy projects are subject to federal regulations protecting surface waters and wetlands, such as the Clean Water Act. If a project disturbs one acre or more, or is part of a larger project disturbing one acre or more, the project developer must comply with National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) requirements. Compliance involves preparing a Storm Water Pollution Prevention Plan in order to obtain an NPDES permit, which is issued by the state’s environmental regulatory agency. Section 404 of the Clean Water Act may also apply if the waters of the United States are potentially affected. Before construction begins, the developer also must ensure that the requirements of various federal laws and regulations protecting historic and archeological resources are met. Provisions such as these apply to all types of construction, not just wind energy, and we will not consider them in any detail here.

State and Local Regulation of Wind-Energy Development

Most regulatory review of wind-energy development takes place at the state or local level, or some combination of them, and most energy development has been on private land, although a few states have anticipated that wind-energy projects could be proposed for state-owned land. In reviewing state and local regulatory frameworks, the committee found it difficult to be sure that we understood these frameworks and their implementation accurately. There are several reasons for our uncertainty:

-

The written regulations themselves are often complex and sometimes apparently contradictory.

-

Aspects of their implementation are often discretionary, making it hard to summarize the true effects of the written regulations.

-

Regulation of wind-energy development is new for most jurisdictions, so both the regulations themselves and the procedures for implementing them are evolving and precedents are being set gradually through experience.

Because of the rapidly changing nature of regulation of wind-energy development, the committee examined records from several recent wind-

energy proposals to see how the regulatory process is working in practice, as well as reviewing the regulations themselves.

State-Owned Lands

Some states have developed policies with regard to the use of stateowned lands for wind-energy development. The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources has completed draft criteria for siting wind-energy projects and a GIS screening tool to guide consideration of the appropriateness of commercial-scale wind-energy development on a small portion of state forestlands (PADCNR 2006).

The state of Vermont has decided that commercial wind-energy development is not an appropriate use for state-owned lands, but that smallscale individual turbines would be appropriate for powering state facilities (VTANR 2004).

Privately Owned Lands

All of the federal regulations described in the previous section as applying to wind-energy developments or other construction activities, regardless of ownership or funding, apply in addition to the state and local regulations discussed here. In some cases, there are state and local regulations that parallel federal requirements. Many states have their own regulations for endangered species, water quality, and so forth. In the Mid-Atlantic Highlands, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia have state laws protecting various animals and plants (Musgrave and Stein 1993); West Virginia does not (WVDNR 2003). States assemble their own lists of species protected under these laws and may include species not listed at the federal level.

Also, most wind-energy projects undergo some type of local review through local zoning and related ordinances. These local ordinances will not be discussed in detail, unless they are the only level of review or when the local provisions are particularly salient for wind-energy projects (e.g., noise or height ordinances). State and local regulations that govern construction and development projects typically apply to wind-energy projects as well.

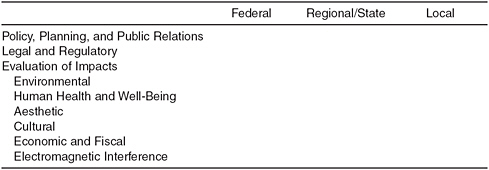

Rather than summarize the regulatory process for particular state or local jurisdictions, we concentrate on several recurring themes, some of which came to our attention during public presentations to our committee and some of which we identified as we examined the regulations for numerous states and municipalities. These themes are: (1) the locus of regulatory review (state, local, or mixed); (2) separation or integration of utility and environmental issues in the review process; (3) the information required for review; (4) the procedures for public participation in the review process;

and (5) balancing the positive and negative effects of wind-energy development. In the following sections, we describe these themes using examples from the Mid-Atlantic Highlands states and elsewhere. Then we critique and interpret some of the same themes, along with some others, in order to identify potential improvements to regulatory processes.

Locus of Regulatory Authority: State, Local, Mixed

Regulatory review of wind-energy development varies considerably. It tends to follow one of three patterns: (1) all projects are handled entirely at the state level, (2) larger projects are handled at the state level and smaller projects at the local level (with the size cutoff varying among states), or (3) all projects are handled primarily at the local level. Many states have some state-level permitting of electrical generation facilities, especially transmission lines. Three of the four states in the Mid-Atlantic Highlands have state utility commissions that oversee proposals for electricity generation and transmission. In Virginia, siting (or expanding) a wind-energy facility falls under State Corporation Commission regulation of electric generation facilities (VASCC 2006a). In Maryland, the Public Service Commission must approve construction of electricity-generating facilities and all overhead electric transmission lines of more than 69 kV (MDPSC 1997). In May 2005, West Virginia finalized specific provisions pertaining to wind-energy facilities in its Public Service Commission procedures (WVPSC 2005). Other states are in the process of incorporating specific language concerning wind-energy projects into regulatory rules and guidelines.

In addition to systems for permitting construction and operation of electricity-generating facilities and transmission lines, approvals are often required to connect wind-generated electricity to regional transmission grids, such as the PJM Interconnect in the Mid-Atlantic Highlands. (The PJM Interconnect covers central and eastern Pennsylvania, virtually all of New Jersey, Delaware, western Maryland, and Washington, D.C. A new control area called PJM West is now covered by PJM Interconnect and covers the northern two-thirds of West Virginia, portions of western and central Pennsylvania, western Maryland, and small areas of southeastern Ohio [Bartholomew et al. 2006]).

In some cases, the developer must obtain a variety of state permits before final review by a local planning or governing body. Sometimes the state regulatory authority coordinates or consolidates these permits. The Oregon Office of Energy encourages developers of smaller wind-energy facilities to obtain permits through the Energy Facility Siting Council rather than dealing separately with the variety of state and local permits otherwise required. They argue that at the state-level siting process there is “a defined set of objective standards,” while “local-level siting is subject to local procedures

and ordinances that vary from county to county and city to city” (White 2002, p. 4). In addition, the Oregon Energy Office states, “Most local land use ordinances address energy facility siting in a superficial way, if they address it at all. It may not be clear what standards the local jurisdiction will apply in deciding whether or to issue a conditional use permit” (p. 4). It notes that “most planning departments around the state have no experience siting large electric generating facilities” (White 2002, p. 5).

Local governments (counties and towns or cities) regulate wind-energy development via local ordinances that apply to any construction proposal. Local regulations, such as zoning of land uses, rights-of-way, building permits, and height restrictions, may constrain wind-energy development. In Virginia, for example, the following local permits were required for the proposed Highlands New Wind Development: (a) a conditional-use permit from the County Board of Supervisors (conditions on height, setback, lighting, color, fencing, screening, signs, operations, erosion control, decommissioning, bonding); (b) a building permit from Highland County; and (c) a site plan approved by the Highland County Technical Review Committee (VASCC 2005).

In Pennsylvania, local regulations constitute the only review, and county governments that issue zoning recommendations and permits for land development and subdivision plans are the regulatory authorities. The Pennsylvania Wind Working Group (which included representatives of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, the Clean Air Council, municipal governments, environmental advocacy organizations, and wind-energy companies) has developed a model ordinance to help local governments carry out this responsibility. The Pennsylvania model ordinance contains no environmental provisions except during decommissioning, when re-seeding after grading is required. It does provide guidance on visual appearance of wind turbines and related infrastructure, sound levels, shadow flicker, minimum property setbacks, interference with communications devices, protection of public roads, liability insurance, decommissioning, and dispute resolution. The model ordinance contains language about waivers of the provisions of the ordinance (PAWWG 2006).

As another example, Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, has developed an ordinance regulating large wind-energy projects, defined as projects with more than 100 kW capacity or a total height of more than 170 feet (Kirby Mountain 2006). This ordinance puts limits on noise (less than or equal to 5 dB(A) above the ambient level at any point on neighboring property). It restricts wind-energy development to areas zoned “agricultural” and puts a one-quarter-mile buffer around any area that is zoned C1-Conservancy or NA-Natural Area or within one-quarter mile of any state or county forest, hunting area, lake access, natural area, or park. It requires setbacks of towers from neighboring properties and from public roads and power

lines. Other requirements include minimum lighting needed to satisfy FAA guidelines, uniform design for towers within one mile, and steps to reduce shadow flicker at occupied structures on neighboring property.

Locus of Review of Environmental Impacts

Another source of variation in wind-energy regulation among different states is how the review of environmental impacts takes place (here, we are treating “environmental” broadly, to include sociocultural effects, as well as effects on the non-human environment). In some states, environmental permitting of wind-energy projects—including their biological, aesthetic, historic, air quality, and water quality considerations—is under the aegis of the public-utility regulatory authority. In other states, this function is performed by another state agency or by a regional or local body. Most wind-energy projects do not have a federal nexus that triggers NEPA review (see above), but some states have their own environmental-review processes that may come into play when wind-energy developments are proposed. New York and California both have State Environmental Quality Review processes (e.g., NYSERDA 2005a) that trigger required EISs in certain circumstances. In New York, for example, the Department of Environmental Conservation classifies actions as Type I (likely to have significant impact, EIS required), or Type II (only local permits required), or Unlisted (may fall into either category). Projects that are 100 feet or taller in an area without zoning regulations that alter an area 10 acres or larger trigger an EIS process; most commercial wind-energy projects would fall in this category.

In many states, the state utilities commission is charged with the authority to weigh environmental impacts, along with other factors, in deciding whether to permit a wind-energy facility to be built and operated, but with provisions for input from other state and federal agencies more knowledgeable about the environment. In Virginia, the Department of Environmental Quality coordinates the environmental review of electricity-generation facilities and may be responsible for issuing certain permits, such as an Erosion and Sedimentation Control Plan or a section 401 permit from the State Water Control Board. It coordinates input from the Departments of Game and Inland Fisheries, Conservation and Recreation, Historic Resources, Transportation and Mines, Minerals and Energy, and the Virginia Marine Resources Commission. However, the Virginia State Corporation Commission (SCC) has the ultimate responsibility for reviewing and issuing construction permits for wind-energy facilities and other electricity-generating units (VASCC 2006a). In West Virginia, the Division of Natural Resources may become involved if permits related to impacts on endangered and threatened species are required (WVPSC 2005). In Maryland, the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Power Plant Research

Program is responsible for coordinating the review of proposed energy facilities and transmission lines with other units within the DNR as well as with other state agencies (MDDNR 2006).

The manner in which environmental information is presented to state regulatory authorities varies as well. In West Virginia, input from the Division of Natural Resources and from the USFWS is presented during the public comment period, which would seem to give it less “weight” than if it were presented in a separate stage of the review process. However, the West Virginia process also requires the applicant to file an affidavit listing any permits required by federal or state wildlife authorities due to anticipated impacts on wildlife (WVPSC 2005). In Vermont, where regulatory review of energy facilities is a quasi-judicial process, the Vermont Agency Natural Resources is automatically a party in the case and makes recommendations during hearings on wildlife studies and other natural resource issues (VTANR 2006).

It is not always clear what roles the environmental agencies will play in permitting decisions. In Virginia, the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (DGIF) coordinates evaluation of effects of proposed projects on wildlife. Although generally supportive of alternative energy sources, including wind, the DGIF voiced substantive concerns about possible effects on birds and bats from the proposed Highland New Wind Development in Highland County to the Virginia SCC. The DGIF asked that the developer provide additional wildlife information and visual analysis, referring to the USFWS guidelines as a standard for wildlife studies that should be provided. The DGIF later wrote to the SCC that the proposed project presents unacceptable risks to wildlife, given that it lacks pre- and post-construction studies of birds, bats, and some other species groups requested by the DGIF, and that it lacks binding requirements for mitigation of adverse effects on wildlife populations. This is strong language from the DGIF, but authority to decide what requirements or conditions to impose on the developer remains with the Virginia SCC (Virginia State Corporation Commission, Case No. PUE-2005-00101, Hearing Examiner’s Ruling, July 11, 2006).

Information Required for Review

Regulatory authorities are charged with weighing a complex mix of environmental, socioeconomic, and cultural factors in deciding whether to permit wind-energy development. Even states that have only local review of wind-energy projects, such as Pennsylvania, prescribe a long list of factors for which the applicant should provide information to the review process (e.g., Lycoming County 2005). Generally, little direction is provided about what and how much information to provide, which leads to a wide variance in the amount and quality of information provided by industry for different

projects. Some states are developing clearer standards through accumulated practice. West Virginia’s recent additions to its utilities review process to address wind-energy development are unusual in prescribing the duration and time of year for studies on birds and bats near proposed wind-energy projects (GAO 2005, p. 31). In some states, pre-hearing conferences are used to identify the types and extent of information that should be provided by the applicant. As illustrated by the Highland New Wind Development case in Virginia (VASCC 2006b), regulatory authorities, other agencies, and parties can request additional information if there appear to be gaps or insufficient information on which to make a decision.

The burden of proof for compliance with regulatory criteria rests almost entirely with the applicant, who usually delegates responsibility for demonstrating compliance to contractors with specialized knowledge. In some cases, regulatory authorities have staff that can provide additional information and review the application for accuracy. In some instances, regulatory authorities may hire independent experts, sometimes at the expense of the developer. In general, it is up to the applicant to provide sufficient information that a decision can be reached, but up to the opposing parties to demonstrate why the standards for acceptance have not been reached.

Public Participation in the Review

It is a well-accepted democratic principle that those whose well-being may be affected by decisions should have a chance to provide input to regulatory processes (see discussion above regarding eight principles for wind-energy regulation, also NWCC 2002). Participation (other than by the applicant and the decision-making authority) is important for securing additional technical expertise, giving a voice to those who might be affected, and conveying information about public values that the decision makers need to carry out the balancing act that the decision procedures require. However, the manner in which input is received varies greatly at all phases of participation. In cases where a proposal for wind-energy development triggers an environmental impact process, whether a NEPA or a state process, as in New York, requirements for public participation may be spelled out as part of the environmental review procedure, although this participation is often late in the process. Elsewhere, requirements for public participation are part of the utilities-review procedure.

The first prerequisite for public participation is that the relevant “publics” should be informed of proposed wind-energy developments. Some state regulations spell out in great detail who should receive notice (and who should give notice) via what media and at what point in the application process. Sometimes the requirements differ according to the size of the proposed project. Some regulatory processes require notification to selected

state, federal, and local government agencies, in addition to adjoining property owners and the general public.

There may be different categories of participation, depending partly on the type of decision process followed in a particular jurisdiction. The most common include an information meeting, in which the developer provides information to the public and answers questions about the project; a site visit, to which both regulators and the public are invited and which may include visits to points from which the project would be visible; a public hearing, during which members of the public can provide comments (usually written comments also are accepted over a designated period of time); and participation in the hearing process. On the less formal end of the spectrum, developers and local and regional governments often organize forums for discussing either specific projects or issues of wind-energy development generally. More formally, in contested cases affected parties can apply for “intervener” status. In Vermont, participants become interveners by demonstrating that they will be materially affected by the project. Interveners often include abutting property owners, town or county governments (e.g., planning commissions), as well as public interest groups, environmental organizations, and business groups that can demonstrate that they have a substantive interest in the outcome, are not adequately represented by another party in the case, and would not unduly delay the proceedings. In states like Vermont where quasi-judicial rules apply to the hearing process, interveners receive all mailings concerning written testimony, design changes, etc. They are entitled to present their own witnesses and to cross-examine witnesses (VTPSB 2006).

In all the processes the committee reviewed, input from participants is advisory to the decision authorities. When agencies or other governing bodies that hold permitting responsibilities could refuse to issue a permit required for construction or operation to begin (e.g., local construction permit), they also function as decision authorities. In other instances, their input to the overall decision authority is advisory and is weighed along with other inputs.

Some jurisdictions, both state and local, have formal processes to receive protests from those who disagree with decisions to permit wind-energy development. Decisions may be appealed to a higher board or the state supreme court. Those who can demonstrate that they have been harmed by wind-energy development may be able to seek damages. Those who are concerned about effects on public resources, such as wildlife or cultural resources, may be able to request modifications of the wind-energy installation or of operating procedures to mitigate harm to these resources, especially if they are in violation of specific provisions of a permit. There may also be processes by which the public can provide notice to public officials if a permit violation has been observed.

Although all the required participation processes we reviewed fall into the more passive, one-way communication end of the participatory spectrum (e.g., officials informing the public or officials receiving input from the public), it appears that both applicants and decision authorities are sometimes taking the initiative to convene more active participatory processes with multiway communication among applicant, decision authorities, other government entities, and affected individuals and organizations. Indeed, the permitting guidelines developed by the NWCC urge proponents of wind energy to begin working with affected communities well before submitting formal applications in order to reduce the likelihood of crippling public opposition later in the process (NWCC 2002). In other countries, such as Britain, Australia, and Denmark, early negotiation with affected communities and likely opponents of wind-energy developments has been identified as essential to eventual success in siting wind-generation facilities (BWEA 1994; AusWEA 2002; Ringkøbing Amt, Møller og Grønborg, and Carl Bro 2002). In Germany a government program designed to provide incentives for public acceptance of wind projects gave residents the right to become investors in local wind-energy projects with direct benefits to their own electric bills (Hoppe-Kilpper and Steinhauser 2002).

In addition to participation as an element of regulatory review, participation in proactive planning for wind-energy development is another part of the public-participation spectrum. At least in theory, comprehensive plans form the basis for zoning ordinances and may inform regulatory processes at the state or local level, especially when there is clear language concerning particular resources and land uses. Some states, such as Oregon, require towns to develop comprehensive plans (White 2002). Wind-energy plans have been critical for siting wind-energy projects in Denmark, as described earlier (Ringkøbing Amt, Møller og Grønborg, and Carl Bro 2002). Public participation at the planning stage helps ensure that the values important to stakeholders and general citizens are reflected in the comprehensive plans that seek to guide wind-energy development.

Balancing Pluses and Minuses

Once regulatory authorities receive information on environmental effects, costs, and technical specifications for proposed wind-energy developments, they are charged to decide whether to allow the development to go forward, and with what, if any, conditions to ameliorate negative effects. Directions for this complex weighing of pluses and minuses of using wind energy are scant and generally limited to general statements about “balancing” interests and acting “in the public good,” resulting in a holistic balancing of positive and negative impacts of the proposed development, rather than a decision based on clearly stated decision criteria. Often, the direction

to regulators appears to presume approval unless serious difficulties with the proposed development become evident. In Virginia, an applicant must show the effects of the facility on the reliability of electric service and the effects on the environment and on economic development, and why the construction and operation of the facility would not be contrary to the public interest (VASCC 2006a). In Vermont, the Public Services Board weighs overall public benefits (need, reliability, economic benefit) against impacts to the natural and cultural environment (VTPSB 2003). In West Virginia, the utilities commission is directed to balance the public interest, the general interest of the state and local economy, and the interests of the applicant (WVPSC 2006a). In some cases the general public good inherent in providing electricity may be judged to outweigh some level of other impacts. This weighing of public good against impacts can be informed by review criteria; by evidence presented; by state energy plans or policy, if they exist; or by precedent. The state may apply conditions to minimize adverse impacts on the environment, including scenic and cultural resources. The applicant can be required to mitigate adverse impacts involving views, noise, traffic, etc.

Some states have articulated standards for making wind-energy regulatory decisions (e.g., State of Oregon 2006). However, specific criteria for different elements of the regulatory review, such as assessment of environmental effects, often are lacking. In Maryland, applicants are required to comply with environmental regulations, and conditions may be imposed to mitigate adverse impacts on environmental and cultural resources, but what constitutes compliance and what may be required for mitigation are open to interpretation in particular cases. Maryland’s Wind Power Technical Advisory Group, a non-regulatory body from the Power Plant Research Program, has recommended standards for siting, operating, and monitoring wind-energy projects to minimize negative effects on birds and bats (MD Windpower TAG 2006). Sometimes more specific criteria are found in case law rather than in statutes. Vermont, for example, developed a much more detailed process known as the “Quechee Analysis” for analyzing visual impacts as part of case history, which has become an integral part of the regulatory criteria (Vissering 2001). Maine has developed guidance for review of development within the Unincorporated Territories (Maine Land Use Regulatory Commission 1997), but it has not been updated to address some of the specific attributes of wind-energy projects. The best processes provide a detailed framework that asks critical questions, along with a framework for determining how the outcome should be judged.

The same lack of definite criteria applies to post-construction operation, although some jurisdictions are working on specific monitoring criteria. In Virginia, the DGIF supports setting a threshold for implementation of mitigation measures if more than 1.8 bats or 3.5 birds are killed per turbine per year. Research is currently being conducted on new technologies

for deterrents or mechanisms that reduce mortality of bats and birds. As these mitigation measures become available, the DGIF recommends their pre- and post-construction implementation in consultation with naturalresources agencies (VADEQ 2006).

A Critique of Planning and Regulatory Review

Wind energy is a recent addition to the energy mix in most areas, and regulation of wind-energy development is evolving rapidly. Our review of current regulatory practices captures only a snapshot of a changing landscape. Regulatory authorities, wind-energy developers, affected citizens, and non-governmental organizations promoting and opposing wind-energy projects are learning as they go. In this section we move beyond simply describing the current status of planning and regulation of wind-energy development to evaluating the merits and deficiencies of current processes and suggesting where and how they might be improved. We call attention to some cross-cutting themes affecting regulatory review of wind-energy development: (1) the interactions among choosing the locus of review, balancing competing goals, and facilitating public participation; (2) the merits of flexible versus more rigidly specified review processes; (3) cumulative effects of wind-energy development; (4) long-term accountability for both positive and negative effects of wind-energy development; and (5) assistance to improve the quality of decisions about wind-energy development.

Interaction of Locus of Review, Balancing of Interests, and Public Participation

In analyzing different types of regulatory processes, the committee found variation ranging from reviews conducted almost entirely at the state level to those conducted almost entirely at the local level. Choosing a level for reviewing wind-energy development is likely to imply some corresponding consequences for the balance of competing interests and for the structure and content of public participation in decisions. These corresponding consequences may not be intentional and the connection to level of review not explicit. Several states seem to be moving toward state-level review, perhaps because of concerns about potentially inequitable decisions in different locations and the inexperience inherent in local review. Oregon, for example, encourages developers to select state rather than local review by offering a more streamlined process at the state level (White 2002). Review at a scale larger than local allows implementation of a rational power-generation network with oversight of potential cumulative impacts.

Putting utility regulation at the state rather than local level implies that there is a public interest that is broader in scale, and greater in importance,

than strictly local interests. If the preceding is true, then environmental and societal costs of wind-energy development, evaluated at site-specific, local, and regional scales, must be weighed against public benefits that might be realized at the state level or beyond. Some states have examined this tension between local and broader interests quite explicitly. For example, Vermont created a Commission on Wind Energy Regulatory Policy in 2004 to recommend changes to the current regulatory process (Vermont Commission on Wind Energy Regulatory Policy 2004). One issue of concern was whether wind-energy projects should be reviewed under the State’s Public Service Board, which reviews all public-utility projects, or whether review should be made under the more localized District Environmental Commissions, which focus on land use. That report represents a thoughtful and deliberate consideration of the implications of level of review for how local versus broader-scale interests are to be weighed in decisions about wind-energy development. The Vermont analysis confirmed the choice of a state-level review process, where public interest on a broad scale is weighed against possibly adverse effects at the local level, but it also recommended increased protection for local interests during the process through aggressive public notification and public participation.

One of those increased protections concerns the manner of public participation in the review process, another arena where choosing the level of review may implicitly determine who has standing as a participant in the review process and how they can participate. Where review is strictly local, broader interests may have less opportunity to be heard. These broader interests may include people beyond the wind-energy development site who would like to receive the benefits of wind energy, and regional or national organizations advocating the protection of wildlife and humans from possibly harmful effects of wind-energy development. Some more-formally constituted participatory processes, such as quasi-judicial hearings, specify how individuals or organizations may petition for an enhanced status. For example, they can be designated “interveners,” which entitles them to privileges such as cross-examining experts and receiving copies of all filings in a contested case. The Vermont Commission on Wind Energy Regulatory Policy made numerous recommendations concerning public participation in the regulatory process, addressing issues such as advance notice to communities and affected individuals prior to filing, the number and timing of public hearings, the definition of “affected communities,” and information and assistance to increase public understanding of and participation in the regulatory process.

Another matter that may be affected by level of review is equity with respect to socioeconomic class, race, or ethnicity of citizens living near wind-energy facilities who are most susceptible to local adverse effects. Environmental-justice issues most often are raised where locally contro-

versial facilities are sited disproportionately in low-income or otherwise politically weak neighborhoods, where citizens may lack educational and political resources to represent their own interests effectively. Here, level of review may cut both ways: developers might take advantage of strictly local review to site facilities where oversight is weak, or state-level review might consistently place the interests of the larger public ahead of the interests of a politically weak local population. These concerns may be less likely to arise for wind-energy facilities than for other types of locally controversial facilities, because the technical requirements for successful wind-energy development constrain the location of facilities so tightly (at least on land).

Both developers and regulatory authorities can take the initiative to foster public participation in wind-energy development, rather than stopping at the minimum needed to satisfy regulatory requirements. Local and state governments can invite public participation in proactive planning for wind-energy development to learn how stakeholder groups and the general citizenry view opportunities and obstacles. Developers could meet with adjoining landowners, community groups, and environmental organizations during the pre-application phase to hear concerns about a proposed project, giving them the opportunity to make changes that decrease the likelihood of public opposition. To prepare for this involvement, developers may benefit from providing descriptions of the proposed project and rationale for selecting the proposed site rather than an alternative for the public to review. Regulatory authorities can solicit public participation beyond required public notices and public hearings to bring local knowledge about environmental and cultural resources into the decision-making process and to satisfy procedural justice concerns for representation of those affected by regulatory decisions.

Optimizing Flexibility, Rigor, and Predictability of Regulatory Review

Processes for reviewing wind-energy proposals vary in the formality of the process and in the degree to which timelines and decision criteria are specified in advance. There are tradeoffs between the predictability and rigor that may be achieved with processes that are more formal and more clearly specified, and the flexibility and adaptability that may be achieved with processes that are less formal and less clearly specified. For example, many review processes specify a timeline for various stages of the review (e.g., submission of technical information, notification to affected publics) or specify a deadline for the regulatory authority to respond to the request for permission to construct a facility. Having specific timelines and deadlines protects developers, regulators, and the public from the extended uncertainty that might accompany a drawn-out review process. However, one notable characteristic of wind-energy proposals is that they vary enor-

mously in the complexity of potential effects. This complexity suggests that a more-flexible timeline would allow both complex and simple projects to meet common standards for quality of information submitted and quality of evaluation of that material by regulators and the public. In Vermont, rather than specifying the same deadline for all utility proposals, state statutes require the utilities board to set timelines for each proposal based on its complexity; once set, all the parties to the review are held to the timelines (Vermont Commission on Wind Energy Regulatory Policy 2004).

In evaluating current regulatory-review processes, the committee was struck by the minimal guidance offered about the kind and amount of information that should be provided for review; the degree of adverse or beneficial effects of proposed developments that should be considered critical for approving or disapproving a proposed project; and how competing costs and benefits of a proposed project should be weighed, either with regard to that single proposal or in comparison with likely alternatives if that project is not built. This lack of guidance leaves a lot to the discretion of regulatory authorities and the other agencies that review elements of the proposed project, making both developers and the public vulnerable to inconsistent requirements among proposed projects and among potential locations. It also has limited our knowledge of the impacts of wind-energy development on human and natural resources. As regulatory authorities accumulate experience with wind-energy proposals, conventions are developing for how much pre-project study of bird and bat activity should be done or what level of bird or bat mortality at operating wind-energy projects will be considered cause for remedial action, as Virginia DGIF has done in recommending limits for bird and bat mortality in comments on the proposed New Highland Wind Development (VADEQ 2006). Nevertheless, there is still something to be said for letting the context of a particular wind-energy proposal set the requirements for information and the thresholds for regulatory decisions, as the Vermont process does for setting the timeline for review. Such flexibility could optimize the expenditure of both private and public resources on information collection and review by focusing on the particular elements most likely to be troublesome for a particular project. However, this degree of flexibility requires a great deal of trust in the judgment of the regulatory authority by developers and the public.

Proactive planning for wind-energy development at state and local levels could give valuable direction to regulatory review by articulating public values that might be affected by projects (e.g., local aesthetic values or socioeconomic concerns, such as effects on tourism). These values, as translated into planning guidelines and local zoning ordinances, help set standards for regulatory review.

There are advantages and disadvantages to giving regulators more direction on how to weigh competing costs and benefits of proposed wind-