1

Guiding Perspective: The Learning Healthcare System

OVERVIEW

This volume reports on discussions among multiple stakeholders about ways they might help to transform health care in the United States. The U.S. healthcare system is large, multifaceted, unorganized, and influenced by so many commercial forces, interest groups, and myriad decision points that it is sometimes described as a “nonsystem.” This character translates also to the challenges of evidence development and application, with fragmentation and silos of expertise, services, and knowledge, as well as gaps in quality and shortfalls in the ability to translate biomedical research into clinical treatments and improved health outcomes (Institute of Medicine, 2000, 2001, 2007). The various sectors involved in the U.S. healthcare system share an interest in delivering better value for our healthcare investments, and many are working to achieve change. Some efforts have resulted in important movements in specific areas, such as quality improvement and assessment of the clinical evidence, but stronger efforts are needed to coordinate these reforms across the many component sectors of the U.S. healthcare system. In particular, stakeholders in the healthcare system need the opportunity to discuss and collaborate on issues of common concern and to identify areas in which they may work collectively.

The Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine was convened as a forum to facilitate collaborative assessments and actions needed to help improve the way evidence is generated and applied to improve health care. The participants define evidence-based medicine as the notion that “to the greatest extent possible, the decisions that shape the health and health care of

Americans—by patients, providers, payers, and policy makers alike—will be grounded on a reliable evidence base, will account appropriately for individual variation in patient needs, and will support the generation of new insights on clinical effectiveness” (IOM Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine, 2006). As a tangible focus and as a means of charting progress, Roundtable members specified a goal that by 2020, 90 percent of all clinical decisions will be supported by accurate, timely, and up-to-date clinical information and will reflect the best available evidence. In preparation for a workshop to consider the possibilities for collaboration within and between sectors on behalf of better evidence in health care, the Roundtable initiated a sector-by-sector strategy assessment process.

This effort, described below, engaged dozens of participants from multiple sectors in coordinated work to identify opportunities within and among sectors to improve value in health care by making the evidence needed more widely available and used. The content of these discussions was captured in papers authored by participants and presented at the workshop. This publication summarizes the elements of their discussions and presentations at the July 2007 workshop on sectoral strategies, entitled Leadership Commitments to Improve Value in Health Care.

THE LEARNING HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

The context for the work is set by the Roundtable’s commitment to work toward building a learning healthcare system. Rapid advances in scientific understanding of the basis of disease and the quickening pace of technological change present challenges to improving the development and application of evidence common to all healthcare sectors. Although evidence-based medicine sets a basic standard of care that patients should expect, it must be delivered by a system that learns, in which evidence development and application are built into the routine processes of care and results are fed back into the system to improve the entire healthcare system.

To characterize the learning healthcare system and explore the key advances needed, the Roundtable initiated the Learning Healthcare System series of workshops to build on the findings and recommendations of earlier Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports on the need for system reform (Institute of Medicine, 2000, 2001). The inaugural workshop in the series discussed key elements of a learning healthcare system, as summarized in the Annual Report of the Roundtable, Learning Healthcare System Concepts v. 2008 (Institute of Medicine, 2008).

-

Continuous improvement in the value delivered. A learning healthcare system is one that maintains a constant focus on the health

-

and economic value returned by care delivered and continuously improves in its performance.

-

Learning in health care as a partnership enterprise. Broad culture change is needed to enable the evolution of the learning environment as a common partnership of patients, providers, and researchers alike.

-

Developing the point of care as the knowledge engine. Given the rate at which new interventions are developed, along with new insights about individual variation in response to interventions, the point of care must be the central focus for the continuous learning process.

-

Full application of information technology. The rate of learning—both the application and the development of evidence—will depend on the full and strategic application of information technology, including electronic health records central to long-term change.

-

Database linkage and use. The emergence of large, electronically based datasets offers important new sources for quality improvement and evidence development. Progress requires fostering interoperable platforms, linking analyses, establishing networks, and developing new approaches for ongoing searching of the databases for patterns and clinical insights.

-

Advancing clinical data as a public utility. Meeting the potential for using new datasets as central sources of evidence on the effectiveness and efficiency of medical care will require recognition of their qualities as a public good, including assessing issues related to their ownership, availability, and use for real-time clinical insights.

-

Building innovative clinical effectiveness research into practice. Improving the speed and reliability of evidence development requires fostering development of a new clinical research paradigm—one that deploys careful criteria for trial conduct, draws clinical research more closely to the experience of clinical practice, advances new study methodologies adapted to the practice environment, and engages cultural incentives to foster more rapid learning.

-

Patient engagement in the evidence process. Accelerating the potential for better development and application of evidence requires improved communication between patients and healthcare professionals about the nature of the evidence base, and the need for partnership in its development and use.

-

Development of a trusted scientific intermediary. Greater synchrony, consistency, and coordination in the priority setting, development, interpretation, and application of clinical evidence requires a trusted scientific intermediary to broker the perspectives of different parties.

-

Leadership that stems from every quarter. Strong, visible, multifaceted leadership from all involved sectors is necessary to marshal the vision, nurture the strategy, and motivate the actions necessary to create the learning healthcare system we need.

These basic elements of healthcare innovation and progress were revisited throughout the workshop and served as the common point of reference for sectoral perspectives.

THE SECTORAL STRATEGIES PROCESS

The IOM Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine initiated the sectoral strategies process (see Appendix A) in January 2007. Key participants were from sectors represented on the Roundtable: patients, healthcare professionals, healthcare delivery organizations, healthcare product developers, clinical investigators and evaluators, regulators, insurers, employees and employers, and information technology developers. Coordinators were identified by Roundtable members for each sector and were asked to reach out to their sectoral colleagues to help describe that sector’s perspectives on relevant key issues and opportunities, as well as a collaborative program of activities that could be used to address them. The final content and structure of these statements were left to the discretion of each group, but the process was guided by a shared vision for healthcare improvement, a perspective informed by the key characteristics of a learning healthcare system and a focus on three central system elements: patients, providers, and the stewardship of evidence.

The sectoral strategies process was conducted over several months in 2007 and included the following activities:

-

January: the initial formation of nine Roundtable sectoral discussion groups

-

February and March: reaching out to other sectoral participants in preparing background material

-

April: completion of circulation of strategy background paper to sector participants

-

May: circulation of sector review draft to Roundtable members in each sector group

-

June: consolidation of draft sectoral background papers and dissemination to all Roundtable members

-

July: presentation of authored background papers for discussion at an IOM workshop on sectoral strategies

The process culminated in the July 2007 workshop Leadership Commitments to Improve Value in Health Care: Finding Common Ground, which aimed to

-

consider ways in which major healthcare sectors can contribute to transformative progress toward the development of a learning healthcare system and achievement of the Roundtable’s goal for improvements in evidence-driven health care;

-

explore, from the perspective of these major sectors, some immediate opportunities for action both within and among sectors, and discuss approaches to taking those steps; and

-

through focused discussion around specific crosscutting issues, develop suggestions for collective efforts—through the Roundtable and beyond—to support the highest-priority transformational initiatives.

PATIENTS, PROVIDERS, AND STEWARDSHIP OF THE EVIDENCE

The workshop began with presentations from perspectives that are central foci of concern and attention regardless of the sector: patients, providers, and issues in stewardship of the evidence. Primary among these are the patients and providers, whose needs each sector endeavors to support. Also vital to health care is the stewardship of clinical evidence, a responsibility that all stakeholders share. Perspectives on these three components of the healthcare system were presented at the workshop to emphasize their fundamental importance and to orient the discussion toward opportunities for collaborative work. Three individuals were asked to present the ideal healthcare system experience from the perspective of patients, providers, and the stewardship of the clinical evidence. These perspectives, described below, provide a rich set of observations illustrating the myriad issues that must be considered to draw on the best evidence and provide the care most appropriate to each patient.

Patients

Margaret C. Kirk1

To provide a simple illustration of one of the challenges of moving the current patient experience to the ideal, consider the following situation: a

woman has just received a diagnosis that her breast cancer has returned and has metastasized to her spine. She had previously had a mastectomy and 2 years earlier had completed her second course of chemotherapy, which was, of course, intended to be her last. She thought that she was through battling the disease, but, in fact, her cancer has returned and her life is once again thrown into confusion. She has so many questions: “Why did this happen?” “Can I really make it through chemotherapy again?”

In one scenario, imagine that this patient is 38 years old with three children living at home. In another, she is a 65-year-old retiree with a husband of 40 years; both are looking forward to spending more time visiting their two grown children and grandchildren. In yet another scenario, she is an 80-year-old widow with three middle-aged children and eight grandchildren. On the surface, at least, each of these patients has the same medical diagnosis. However, when their backgrounds are considered, it becomes clear that these three patients cannot be thought of in monolithic terms when potential treatment plans are evaluated.

One important challenge in health care is to develop an evidence base that acknowledges that even with identical diagnoses, patients’ life stages, underlying health, social support networks, attitudes about health and illness, faiths, cultures, and many other factors are important considerations in determining the course of treatment appropriate for each patient. The ideal patient experience would have to include the patient and his or her family as respected members of the healthcare delivery team from the outset of treatment decisions, which is equivalent to the National Health Council’s definition of “patient-centered care.” Although various stakeholders have emphasized the central role of patients and the importance of evidence-based medicine, the perspectives of these patients—the group that all other stakeholders in the healthcare system serve—must still be heard. Although it is assumed that all stakeholders work in the patient’s best interest, the competing interests at play create an urgency, from the patient’s perspective, to better understand what it will take to build an evidence base in which his or her unique needs remain at the forefront.

Evidence-based medicine is a powerful tool that can be used to ensure the best possible medical outcome, and when it is used in the context of a strong patient-provider relationship, it is a necessary component of an ideal patient experience. It can help close the quality chasm across geographic regions, treatment settings, and socioeconomic levels. It also channels resources to their most effective use. The challenge, however, is to balance the nation’s urgent need to ensure quality care and to use resources wisely with the understanding that patients react differently to different treatments and have different priorities and personal values with respect to different treatment options. In some cases, patients have reported the use of evidence or a lack of evidence to deny Medicaid coverage for various

treatments for asthma, epilepsy, and depression. Although this shortsighted view may save money for the payer in the near future, it could also result in costly emergency room visits and hospitalizations as well as physical and emotional suffering for the patient, all of which might have been averted if care had been delivered in a timely and an appropriate manner.

For evidence-based medicine to be applied systematically, it must be structured to support the reality that what works for most patients may actually cause harm or be inappropriate for others. In other words, as an epidemiological view is embraced and public health decision-making models are used, providers should also remember and embrace the promise of personalized medicine. In the patient-centered world of personalized medicine, individual patient data in the hands of an individual healthcare professional are given equal standing with aggregated public health data. The pressure to use evidence-based medicine thus sometimes seems counter to the goals of personalized medicine, because it tends to measure outcomes in a population rather than a personal level. Decisions based on evidence that also account appropriately for individual variation in patient needs are, of course, the ideal and the goal of both evidence-based medicine and personalized medicine.

The focus should not be which medicines work the best, the fastest, or the cheapest but, rather, which treatment options are available under different circumstances and how they are best communicated to individual patients. Most of the data currently available tend to be cost based instead of informing best practices or even relative costs. The healthcare system needs to move beyond “one size fits all” to which treatment will work best for the individual patient. Breast cancer is one of the few areas that is building a body of research to allow more individualized treatment plans, but this kind of information has begun to be developed for few other chronic diseases. In research carried out in the future to expand the evidence base, improved transparency of research at the bedside will help patients make better-informed choices.

To facilitate patient-centered care, increased attention around better understanding of patient needs is also warranted. Although many stakeholders in the healthcare system have come together to improve the effectiveness, safety, efficiency, and affordability of health care, these efforts seldom acknowledge that engaging patients more fully in their own care can positively affect medical outcomes. To make progress, communication is key. It is crucial to utilize the higher standards of clear health communication in which the components of the healthcare industry and healthcare professionals engage in useful dialogues with patients. An emphasis on and the utilization of clear health communication principles is essential to avoid patients’ misunderstanding and mistrust of the information they receive.

The National Health Council has done extensive research on communicating with patients on a variety of health topics. The council’s findings consistently show that language, tone, content, and context should not be taken for granted. As a successful example, the Y-ME National Breast Cancer Hotline empowers those touched by breast cancer with ways to communicate with their healthcare providers, encouraging callers to “become the lead player on their healthcare team.” There is also the Partnership for Clear Health Communications and its Ask Me 3 program, which encourages patients to ask and keep asking three critical questions until they get satisfactory answers (National Patient Safety Foundation, 2008): (1) What is my main problem? (2) What do I need to do? (3) Why is it important for me to do this? In addition, the National Breast Cancer Coalition has been successful in creating models for survivors to be more fully informed about their future treatment options and engaged in choosing from among those options, specifically through education, advocacy, and participation in the U.S. Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program; but there is still a need for a more systemic effort to address communications.

If providers truly wish for patients to comply with medical advice or, rather, to mutually agree to share responsibility, then every communication must be carefully planned, tested, and refined to effectively influence the audience. In addition, there should be a clear distinction between health communications and health literacy. Although the onus is largely on providers to communicate health information more clearly, health literacy involves reaching a much larger audience and perhaps a complete overhaul of educational and cultural systems. There have been several proposals for improving the ability of healthcare professionals to communicate more effectively with patients, including financial incentives and additional classes as part of the educational process.

Finally, patients must perceive the problem before they seek a solution. Studies have shown that to patients, quality or a lack of adherence to evidence-based guidelines is not their primary concern. In fact, most patients are unaware that the care they receive may not be the best and, therefore, have little perspective from which to judge the evidence. Demonstrating to patients the current lack of evidence and its impact on improving the health care that they receive will help them better understand the importance of evidence. All stakeholders must be willing to explain the value of evidence to patients and demonstrate how it can be used to improve their health care, health, and well-being. There must also be built into the system a mechanism that informs and educates patients about all options based on good evidence, including securing second opinions, but that allows patients and their caregivers to ultimately decide what is the right treatment for their unique personal circumstances. In this area also, additional research must be done on the best ways to meaningfully involve

patients in these difficult decisions. Such true engagement of the patient and clear and honest communication about evidence-based medicine will help to raise awareness and address the misperception that “the system” is simply using evidence to limit access to care. It only makes sense that the patient who has an understanding of the evidence will make better decisions regarding his or her health care

In short, the key is protecting, honoring, and establishing the patient-provider relationship such that the parties are on equal footing and the relationship carries the same weight as public health and epidemiological evidence when providers and patients make clinical decisions. To do this, communication is essential. It is crucial for all stakeholders to begin the difficult work to achieve this goal. To quote my mother: “If it was easy, everybody would be doing it.” The task is not easy, but we simply must make it happen.

Providers

Terry McGeeney2

Several years ago, the seven family medicine organizations realized the need for a fundamental change in the specialty within the U.S. healthcare system. In response, the Future of Family Medicine Project emerged in 2001 to assess the healthcare and technology needs of patients and providers and to identify the fundamental changes necessary to address these issues and transform family medicine. The final report highlighted existing issues in the practice of family medicine and identified a new model of practice that employs a patient-centered team approach, eliminates barriers to access, advances the use of information systems and electronic health records, operationally redesigns offices to function more efficiently, focuses on quality and outcomes, and improves overall practice finance and cost savings (Martin et al., 2004; Spann, 2004).

The report also called for the creation of a financially self-sustaining national resource to provide practices with ongoing support during the transition to a new model of family medicine, thus inspiring the genesis of TransforMED, a practice redesign initiative affiliated with the American Academy of Family Physicians, which seeks to lead and empower family medicine practices and transform the specialty of family medicine and which is the reference point for the issues discussed here. Several lessons have emerged from the current work that can inform the development of

a learning healthcare system and identify the steps needed to achieve the Roundtable’s goal.

The model of care emphasized in this work is that of the “personal medical home.” The medical home model represents the transformation of the family medicine practice experience in which the principles of patient centeredness, a whole-person orientation, and a continuous relationship between the provider and the patient guide patient care. As of the date of the workshop, four primary care organizations representing 365,000 physicians had signed on to this model, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Family Physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the American Osteopathic Association. Key supporting elements of this model include patient access to care, patient access to information, information systems such as electronic health records with point-of-service reminders of best practices, redesigned offices to increase practice efficiency, an increased focus on quality and safety, efficient practice management, the provision of point-of-care services, and a team approach to providing care within the practice (TransforMED, 2007).

Two components are of particular importance. First, information systems, including those that provide information for patients such as online portals with laboratory results, online appointment scheduling, and electronic (or virtual) visits, hold great promise for improving care. However, emphasis is needed not only on the implementation of such systems but also on ensuring that patients have access to the necessary technology (e.g., computers) to connect with these information technology resources. Second, high-quality point-of-care services, including wellness promotion, disease prevention, and acute and chronic disease management services, depend on the adoption of a team approach to care. To make this work, practices will have to accept greater responsibility for their patients’ care as a whole and work to coordinate their care with other providers. This is not the sole responsibility of the provider. The development and utilization of a multidisciplinary team approach that includes those inside and outside the practice—colleagues in mental health and community health centers, social workers, pharmacists, and physical therapists, as well as nurse practitioners and physician assistants—will be particularly important in the face of emerging healthcare workforce shortfalls to ensure the provision of appropriate and timely care. In addition, the provider is not the sole decision maker but provides information and support to allow the patient to participate in decisions affecting his or her own care and wellness.

To demonstrate the value of this model of care, a 2-year national demonstration project is under way and is funded in part by the American Academy of Family Physicians and in part by the Commonwealth Fund. The purpose of the national demonstration project is to demonstrate that the new medical home model of care enables providers to deliver higher-

quality, patient-centered care that results in improved patient satisfaction and improved practice staff satisfaction while providing a successful business model for the practice. The national demonstration project has been deemed a learning laboratory that has evaluated initiatives addressing various points along the continuum of providing medical homes for patients. For example, the residency-based demonstration project, referred to as Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice, seeks to train family physicians for practice in the twenty-first century with a prominent focus on evidence-based medicine and technology. Since existing residency training methods have not significantly evolved since the 1970s, this project examines new techniques for improving the training of primary care physicians.

Some initial results from previous national demonstration projects mark the potential of this approach. For example, some studies have indicated that at present, most providers either completely lack the ability to use information systems or underuse them. By one estimate, only 10 percent of practices use their information systems to their fullest capacity. Within family medicine practices, 40 percent use electronic health records, which is up from 30 percent just since 2006. However, a national study that focused on improving the use of electronic health records and information systems indicated that that proportion has already risen to as high as 42 percent (Center for Health Information Technology, 2007).

In addition to physician training and the utilization of electronic health records, the current practice experience falls short of the ideal in many areas. Evidence-based medicine is poorly defined and poorly understood; queries for evidence to inform clinical decisions are inefficient and often produce information that is outdated or not useful for decision making. For example, outcomes are typically measured only in the context of payment, with little value placed on outcomes important to patients (patient feedback and information on patient satisfaction are not actively sought). Also, because many practices do not look for opportunities to improve efficiency, acute care is often not available because of scheduling constraints, chronic care is episodic and fragmented, and prevention and wellness services are viewed as afterthoughts and often are not reimbursed.

A key contributing factor endemic to current medical practice is the perception that the doctor is the “captain of the ship,” a view that does not allow coordination in the provision of health care or the use of multidisciplinary team approaches to care. Regular, productive staff meetings are nearly nonexistent and contribute to low staff morale and increased office inefficiencies. Compounded by the lack of an efficient workflow and support systems, these issues result in long delays in patient follow-up, difficulty with information gathering, and problems with appointment scheduling.

To overcome these current problematic patterns, the most difficult challenge may be to change the culture of medicine itself. Most people outside

of medicine do not know or understand that the culture of medicine needs to change, let alone that physicians and practices are not equipped to make the challenging and difficult transition. To illustrate the resistance to change in the medical community, consider a description of the stethoscope from a nineteenth-century London Times editorial that now is obviously quite shortsighted:

That it will ever come into general use, notwithstanding its value, is extremely doubtful because its beneficial application requires much time and gives a good bit of trouble, both to the patient and to the practitioner, because its hue and character are foreign and opposed to our habits and associations.

In addition to a culture of medicine that strongly resists change, other barriers to achieving the ideal exist. Misaligned incentives are present at all levels, greatly adding to the inefficiencies and costs of care. For example, because payments for procedures are often higher, healthcare professionals could be encouraged to perform more procedures than necessary instead of providing other effective services, such as cognitive services. Likewise, healthcare professionals employed by hospitals are usually not paid unless an oftentimes unnecessary patient visit is involved—again, prompting avoidable and costly patient care. Finally, there is a lack of incentives for the next generation of healthcare professionals to practice family medicine, where a great deal of care is delivered. In the United States, specialists are paid 300 percent more than primary care doctors. In comparison, in most countries outside the United States, specialty practitioners are paid 30 percent more than primary care doctors (Gajilan, 2007; Snyder, 2007).

Barriers also exist on a basic practice level. For example, a lack of leadership within a practice can stymie progress before it even gets started. Poor communication, poor understanding of the team concept of care, misaligned financial incentives, the silo mentality of care with its lack of coordination and information sharing, and the proprietary nature and lack of interoperability of electronic health record systems with other systems used in healthcare practices—all can combine into an insurmountable hurdle that needs to be overcome.

Providers must be encouraged to overcome these barriers to provide improved care for their patients, such as using evidence at the point of care to determine the proper course of treatment. When it is used at the payer level, the designation “not medically necessary” often prompts procedural, diagnostic, and pharmaceutical coverage denials that waste time and money, creating a tremendous financial drain and barrier to practice efficiency, not to mention creating tremendous tension among all parties—payers, providers, and patients. In addition, improved communication is needed at

the practice level, for physicians as well as patients, on the importance of evidence in improving health and the health care provided. One notable issue is that many of the current evidence-based guidelines serve specialty care well in the context of a narrow focus on limited organ systems. Physicians should be better engaged in the development of evidence by becoming involved in practice-based, primary care-focused research. The key for primary care is evidence-based decision support (not guidelines) that addresses the complexity of the patient in accordance with a whole-person orientation of care.

Care is often inappropriate or delivered without consideration of the available alternatives, as a result of patient pressure or because of narrow information provided by pharmaceutical company representatives. A better understanding of the importance of evidence and the use of evidence-based guidelines by patients and providers alike would help to reduce requests for unnecessary therapies as well as the perception of some physicians that it is more time-efficient to carry out patient wishes than to follow evidence-based guidelines. Physician-patient communication will also be improved by the increased availability of comparative effectiveness information, which will provide physicians with the evidence they need to appropriately tailor a patient’s course of treatment. Furthermore, improved provider and staff satisfaction can lead to a lower level of staff turnover, greater office efficiency, and improved team communication. These improvements lend a greater opportunity to provide patients with a continuity of care—a practice that studies have shown to be important. Patients who have access to comprehensive primary care experience both better health outcomes and lower medical costs (Schoen et al., 2007).

These barriers to progress also have effects on the healthcare system as a whole. All of the barriers listed above, in addition to misaligned and disproportionate financial incentives, result in a continued decrease in interest among medical students to pursue a primary care specialty, contributing to a significant shortage of primary care physicians in the foreseeable future. One of the motivating issues of the demonstration project described above is that transforming medical practices to meet the needs of today’s patients and healthcare system, while improving the chance of financial viability of primary care practices, will also increase interest in the specialty.

All parties in the healthcare system—physicians, patients, payers, vendors, and suppliers—are part of the solution in moving clinical practice to the ideal. Cross-sector meetings and collaboration are needed to align incentives and determine how best to provide physicians with the information and flexibility they need for evidence-based decision making. Some opportunities for achieving this transformation include making practices more patient centered by working to communicate better with patients and facilitate shared decision making, rewarding processes and practices that

are based on evidence, and increasing the focus on developing actionable information (for example, diagnostics should provide results that physicians can act on to better treat their patients).

Development of the electronic health data infrastructure will be necessary to bring about the needed transformation, although that action alone is not sufficient to bring about the transformation. Some advances of particular help to providers will be the development of electronic health records that meet the needs of both the provider and the patient. These records should be interoperable with other systems used in healthcare practices so that patient data can be accessed from all sites at which a patient receives care; they should contain evidence-based guidelines that can be accessed easily at the time of care; and they should be linked to population-based registries. These aims could be supported by the development of a national health data repository and the capacity to self-populate electronic health records with patient data. A narrowing of the number of vendors (currently, more than 220 vendors maintain and sell proprietary electronic health record data) might allow the market shift needed to allow greater electronic health record flexibility and data entry. Patient portals should also be supported, particularly if they are based out of the patient’s medical home, to ensure physician access and use to support the continuity of care.

From a coverage and reimbursement standpoint, instead of labeling procedures as not medically necessary, which creates office inefficiency, perhaps the designation “not supported by the evidence” should be used. As opposed to physicians relying on representatives from healthcare product manufacturers to accurately represent their drugs and devices, comparative effectiveness studies must be undertaken regularly. Finally, the medical legal system must be reworked to better support evidence-based medicine: specialists often advise the use of additional tests and local standards of care that take precedence over what is based on evidence.

To make progress toward the Roundtable’s goal, stakeholders must collectively discuss current barriers and take collaborative action to resolve these key issues. The new reality that healthcare providers and all stakeholders should collectively seek is an evidence-based, patient-centered, personal medical home for all. Milestones should be developed to provide practice steps that gauge progress toward a learning healthcare system, including the establishment of a national data repository on quality outcomes, self-populating population-based registries that provide recommendations, and proactive evidence-based patient management. Primary care practices must be encouraged to participate in office-based research that allows the development of meaningful evidence-based decision support at the point of care. This research should also incorporate a proactive means of managing populations of patients with open sharing and adoption of results to maintain a focus on the totality of the patient, not simply a disease or an organ system.

Stewardship of the Evidence

Sean Tunis3

The ideal in health care might be characterized by the utilization of efficient and reliable methods for the development, dissemination, and application of evidence. In focusing on improving the development of evidence and, in particular, on how to move from theory to practice, examples from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Center for Medical Technology Policy (CMTP) illustrate some of the challenges of implementation and offer some lessons and recommendations for future work.

Evidence-based medicine is commonly defined as an approach that “de-emphasizes intuition, unsystematic clinical experience, and pathophysiologic rationale as sufficient grounds for clinical decision-making and stresses the examination of evidence from clinical research” (Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, 1992). In this definition, evidence-based medicine has a function in clinical decision making rather than policy decision making. However, the same definition currently has been adopted for policy making. Therefore, in today’s context, the term “clinical research” might be expanded to encompass broader notions such as “comparative effectiveness research” or “knowledge about what works.”

Evidence is derived through four main methods: (1) systematic reviews of the literature, (2) decision modeling on the basis of literature reviews, (3) retrospective analyses of administrative claims data or electronic health record data, and (4) experimental or observational prospective studies. These four methods vary in terms of the level of confidence in the knowledge generated, as generally reflected in the hierarchy of evidence. For decision making, the evidence gathered by these methods is weighted according to the levels of confidence in and the reliability and rigorousness of the methods.

The issue that emerges, however, is determining when the evidence is adequate to demonstrate that an item or service can improve net health outcomes or can be labeled by Medicare’s standards as medically necessary. The quality of evidence is continuous, with confidence in the evidence ranging from low to high, and a clear inflection point at which the evidence changes from insufficient to sufficient is lacking. Adequacy is a judgment about the evidence rather than a characteristic of the evidence itself.

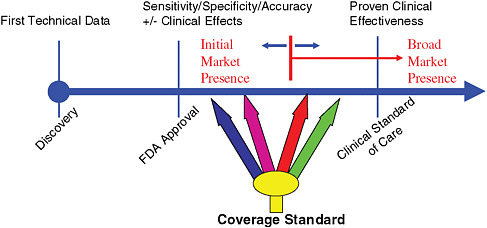

As an example of this dilemma, consider the natural history of a hypothetical imaging technology from the initial development phases through Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and entry into the market-place (Figure 1-1). For a diagnostic method, FDA approval might be granted

FIGURE 1-1 The natural history of imaging technology.

on the basis of initial studies of sensitivity and specificity, and FDA would allow an initial, limited presence in the marketplace. Somewhere between the time of FDA approval and the time of generation of incontrovertible evidence of clinical effectiveness, there is, at least for many payers, a point at which evidence becomes adequate for coverage. However, considerations related to cost, a willingness to support innovation, or the importance of personal choice vary significantly between individual payers. These variations define a range rather than a precise point at which an intervention can be deemed as having adequate evidence to support its use. In terms of evidence-based medicine, it is important to keep in mind that it is not a binary question of whether evidence exists or not but, rather, a question of how a clinical or policy decision is superimposed on the available evidence.

Because many critical healthcare decisions are dichotomous, one approach to coverage policy is to provide some options that meter decision making more precisely to the quality of the evidence. Medicare’s coverage with evidence development policy, for example, provides additional coverage options that are linked to requirements such as patient participation in registries or clinical trials. Instead of a “yes” or a “no” decision, the coverage with evidence development policy allows decisions to be made conditionally on the basis of further data collection and evidence development. Coverage decisions are then revisited when a larger body of evidence is available.

A second example, value-based insurance design (VBID), varies the amount of copayment that patients provide on the basis of the level of evidence or cost-effectiveness of an intervention. VBID is the alignment of clinical and financial incentives to encourage the use of high-value interven-

tions and services that are based on a more solid foundation of evidence. Thus, the more clinically beneficial the evidence suggests that a therapy is, the more out-of-pocket cost savings will a specified patient population receive for using that intervention.

A third approach is the risk sharing on price model, which allows payers to pay a certain price for a newer drug, contingent upon demonstration of long-term benefits and effectiveness. For example, Johnson & Johnson recently reached a deal with the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Clinical Excellence regarding use of the company’s drug for multiple myeloma, bortezomib (Velcade). The drug is made available in the United Kingdom and is paid for by the National Health Service (NHS) based on the expectation that it effectively shrinks a patient’s tumors. Johnson & Johnson has agreed to reimburse the NHS for the full cost of the treatment ($48,000 per patient) if these results are not demonstrated.

The coverage with evidence development, VBID, and risk-sharing price model approaches acknowledge that all of the information needed about a technology or a treatment is not always available at the time of FDA approval. They provide ways to make decisions and postpone further decision making until sufficient evidence is generated, essentially allowing the reimbursement process to move forward and promoting the generation of additional evidence rather than creating a barrier to its generation.

These approaches have not always yielded the desired results, and some useful examples illustrate the many challenges that have emerged upon policy implementation. After years of disputes with the positron emission tomography (PET) scanning community over coverage issues, Medicare adopted a coverage with evidence development approach, paying for the use of this technology only in the context of a prospective registry. Additionally, Medicare agreed to cover PET scans for suspected dementia only in the context of a pragmatic clinical trial. However, although the trial for suspected dementia was designed, it was never funded, and as a result, no coverage for PET scans exists for patients with suspected dementia. In May 2006, the National Oncologic PET registry was initiated under the coverage with evidence development approach and requires self-reporting of changes in patient management by physicians in response to PET scan results. The lack of data on diagnostic utility makes this registry of questionable immediate value. However, 80 percent of PET imaging sites now participate in the registry, making it arguably the largest practice-based research network in the world. By using this approach, an infrastructure for the collection of data from PET imaging sites has been created and could be used for real-world simple trials of diagnostic utility, if funding for such studies were made available.

Encouraged by the potential of these approaches, CMTP has been active in encouraging similar types of work in the private sector. Recent

work by CMTP on a study related to coronary computed tomography (CT) angiography illustrates many of the challenges and issues that an ideal evidence-based healthcare system will have to confront. In April 2006, the Medicare Coverage Advisory Committee reviewed a Duke University evidence-based practice report on CT angiography that found that only 10 studies had been performed at single centers, all with sample sizes of less than 100 subjects, and requested that more research on this intervention be conducted. In the meantime, Medicare coverage for CT angiography will be provided at the local level by use of consensus-based American College of Cardiology appropriateness guidelines rather than research-based guidelines.

To address these issues, a workgroup was convened at CMTP that included all the major vendors of CT angiographs (Siemans, Phillips, General Electric, and Toshiba), key payers (Aetna, Kaiser Permanente, United Healthcare, and BlueCross/BlueShield Association), healthcare professional groups (the American College of Cardiology and the American College of Radiology), and the patient perspective (the American Heart Association). Initially, the group agreed that a potential future use of CT angiography would be for asymptomatic, intermediate-risk patients, and it considered conducting a registry study. However, it was decided that a prospective controlled study was needed, and as discussion progressed, the various perspectives at the table became evident. For example, although the vendors sought to include asymptomatic intermediate-risk patients and intermediate outcomes, the payers thought that such patients should be excluded and sought clinical end points such as cardiac death and myocardial infarction instead. Other questions emerged around the type of coverage policy to be used, specifically whether coverage with evidence development should be applied, because this would effectively constrain use of the technology to those in the trial until initial results became available in 4 to 5 years. The discussion is ongoing and illustrates the point that because perspectives on when the evidence is adequate for decision making differ among stakeholders, arriving at a clear consensus on the additional evidence needed and the methods to be used to obtain that evidence will be a continuous challenge.

In terms of the methodologies used to generate evidence, there is much discussion and certainly some promise in the improved utilization of alternatives to randomized controlled trials as well as the potential data from improved electronic health records. Along with these discussions, the notion has emerged that when the electronic health record is perfected, there will be a substantially reduced need for prospective controlled studies. This belief is bolstered by common negative views of randomized controlled trials: that they are expensive, are slow, and need to enroll very large numbers of subjects; that they often raise more questions than answers and

cannot evaluate effects on typical patients treated by average clinicians; and that they encounter great difficulty both in securing physician participation and in recruiting and retaining subjects. These drawbacks have fueled increased interest in observational methods, claims data, electronic health records, and pragmatic studies or controlled studies in real-world settings and with real patient populations. However, prospective clinical trials will continue to be an important source of information because there are many questions for which it is difficult to control for the baseline differences in patient selection. Therefore, work is needed to better understand the appropriate use of all research activities available. Work should aim to facilitate more pragmatic clinical trials, promote the use of observational methods, and improve the data from electronic health records. The advances needed for these various methods are very different and will entail confronting distinct challenges. Therefore, a real effort should be made to promote all these types of research activities in concert.

Finally, the creation of a central agency for comparative effectiveness studies or a substantial increase in funding for this type of research has recently been proposed as a way to develop the comparative effectiveness information needed. However, a large capacity to support comparative effectiveness research in the form of systematic reviews, clinical trials, and cost-effectiveness modeling already exists, and numerous organizations have undertaken similar activities but have not been successful. Therefore, it is important to consider how these proposals differ and what will allow true progress to be made. Perhaps there will be more funding, greater political insulation through the use of an independent board, greater participation from all stakeholders in the healthcare system, more access to health information technology, more transparency and credibility in the process, increased interest in developing cost-effectiveness or comparative value information, or a larger support base formed on the basis of a greater consensus of the need for comparative effectiveness research. The case has not yet been made clear as to which, if any, of these elements are key to developing the needed information or leading to the improvements in health care that are sought. The worst outcome would be to add millions or billions of dollars to work that has already been done without clarifying why those past efforts have not met the perceived need.

The ideal approach for comparative effectiveness research or evidence generation is not known; however, the important technologies and the priority issues that have to be tackled are well recognized. Rather than priority setting, what is now needed is the willingness to support and try various approaches, including reviewing claims data and using data from electronic health records. All methods and strategies should be advanced and used so that through trial and error, the healthcare system can begin to learn what works. It will be critical to engage stakeholders meaningfully in this process

and maintain patients and clinicians as an organizing focus. Ultimately, all stakeholders seek simply to provide information that helps clinicians and patients make decisions. Therefore, as the creation of an evidence-based healthcare system proceeds, the notion that evidence-based medicine is itself a subjective notion must be remembered.

REFERENCES

Center for Health Information Technology. 2007. EHR adoption. http://www.centerforhit.org/ (accessed May 19, 2008).

Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. 1992. Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 268(17):2420-2425.

Gajilan, A. C. 2007. Analysis: “Sicko” numbers mostly accurate; more context needed. CNN Medical News. http://www.cnn.com/2007/HEALTH/06/28/sicko.fact.check/index.html (accessed June 30, 2007).

Institute of Medicine. 2000. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

———. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

———. 2007. The learning healthcare system. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. 2008. Learning healthcare system concepts, v. 2008. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. 2006. Charter and vision statement: Roundtable on evidence-based medicine. Washington, DC.

Martin, J. C., R. F. Avant, M. A. Bowman, J. R. Bucholtz, J. R. Dickinson, K. L. Evans, L. A. Green, D. E. Henley, W. A. Jones, S. C. Matheny, J. E. Nevin, S. L. Panther, J. C. Puffer, R. G. Roberts, D. V. Rodgers, R. A. Sherwood, K. C. Stange, and C. W. Weber. 2004. The future of family medicine: A collaborative project of the family medicine community. Annals of Family Medicine 2(Suppl 1):S3-S32.

National Patient Safety Foundation. 2008. AskMe3 Patient Brochure. www.npsf.org/askme3/PCHC/download.php (accessed November 2007).

Schoen, C., R. Osborn, M. M. Doty, M. Bishop, J. Peugh, and N. Murukutla. 2007. Toward higher-performance health systems: Adults’ health care experiences in seven countries, 2007. Health Affairs 26(6):w717-w734.

Snyder, D. 2007. Vanishing breed: What happened to the family doctor? Fox News online. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,306439,00.html (accessed October 30, 2007).

Spann, S. J. 2004. Report on financing the new model of family medicine. Annals of Family Medicine 2(Suppl 3):S1-S21.

TransforMED. 2007. The new model. http://www.transformed.com/newModel.cfm (accessed May 19, 2008).