CHAPTER 5

Mineral Information and Possible Initiatives in Research and Education

INTRODUCTION

Minerals, as noted throughout this report, are important to the basic infrastructure of the nation, its productivity, and its economy. Therefore it is vital to evaluate every mineral’s criticality with some regularity and with appropriate data collection and analysis so that decision making regarding critical minerals can occur in a time frame suitable to alleviate potentially disruptive restrictions on mineral availability. Because criticality is dynamic, the criticality of a mineral is really only a snapshot of a mineral’s applications and of the risks to its supply at a given time; mineral criticality can be effectively evaluated only in the context of a continuous stream of baseline data and information.

This chapter discusses the need for the federal government to collect data on minerals, provide analysis of these data (including mineral criticality), and disseminate the data and analyses in a publicly accessible format. The chapter begins with a historical overview of the federal context for statistical data collection and mineral data collection, and follows with a catalogue of public and private mineral databases that can be used

by policy makers, the public, and industry to make informed decisions about a mineral or group of minerals. With mineral criticality as a primary theme, the committee then suggests the types of information and research that could best enable informed decisions about mineral policies affecting the national economy and infrastructure. Finally, because the production and analysis of this information require trained professionals, the chapter surveys the state of education related to mineral resources.

MINERAL DATA AND THE FEDERAL STATISTICAL PROGRAM

The decision by the federal government to collect mineral data is founded on two themes: (1) public understanding of the importance of collection, analysis, and dissemination of statistical data and information about mineral use and demand, mineral production and supply, and other aspects of mineral markets; and (2) support at the highest levels of government for collection of mineral statistical data that address the full life cycles of minerals to inform and monitor public policy. Box 5.1 discusses more conceptually the justification for federal involvement in collection, analysis, and dissemination of mineral information and in mineral-related research.

Historical Perspective

The nation’s historical commitment to mineral data collection has been robust, with support from both executive and legislative branches. Mineral data collection has been a recognized part of national policy since at least World War II (J. Morgan, Jr., personal communication, January 2007). During the past several decades, numerous pieces of legislation have affirmed the federal commitment to collect mineral information with a foundation in the importance of minerals to the national economy and national security. Among them, the National Materials and Minerals Policy, Research and Development Act of 1980 (P.L. 96-479) suggested that “the Executive Office shall coordinate the responsible departments and agencies to identify material needs and assist in the pursuit of measures that would assure the

availability of materials critical to commerce, the economy, and national security.” A report from the Subcommittee on Mines and Mining of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs of the U.S. House of Representatives (U.S. Congress, 1980, pp. 12-13) the same year emphasized further:

There have been no less than 20 mineral or material policy studies that have been prepared or commissioned by one governmental agency or another, as well as others prepared for groups outside government. Additional studies have examined at least some part of mineral policy questions. Although many studies reflected some particular outlook or condition, all adopted as a universal starting point the national significance of adequate mineral supplies and the importance of a strong domestic industry. All agree, to a greater or lesser extent, that foreign imports provide least-cost benefits to the consumer. At the same time, most see the pitfalls of import dependency and how such dependency forfeits freedom to make political, economic, and defense decisions. All strongly urge better governmental analytical capability and improved means of integrating information into a comprehensive picture portraying the synergistic impacts of governmental policies or actions upon industry and, beyond that, the broad national interest [italics added]. In more recent reports, recycling and conservation receive more attention and a progressively stronger case is made for increased government participation in development of long range technological innovation.

A 1982 presidential report on minerals also noted the need to improve integration of mineral concerns into the policy process, suggesting that mineral information was useful to guide decisions on the strategic stockpile, land use, tax and tariff, trade, investment, research and development, and environmental protection, among others (Shanks, 1983).

Historically, then, a supportive federal view of the need to collect mineral information has been one part of the overall federal responsibility toward collection of various types of data for public use. As presented in previous chapters, the need for mineral data is no less important today than several decades ago. In fact, the need for more frequent and detailed

|

BOX 5.1 Mineral Information and Research: Why a Federal Role? The need for information and research on minerals, by itself, does not automatically justify federal government activities. As noted by the National Research Council (NRC, 2003, p. 24): After all, in market economies there are natural and strong incentives for private entities producing and consuming minerals to carry out scientific research and to collect and disseminate information that is relevant and necessary for informed decision making. Nevertheless, in several specific circumstances, private markets are likely to yield suboptimal outcomes from the perspective of society as a whole. Specific circumstances that are relevant when considering critical minerals include the following:

|

analyses of some critical minerals is at present more acute due to the highly global nature of the mineral market and increased global competition for mineral resources. As part of this commitment to federal collection of mineral data, very competent mineral data collection and public dissemination occur now through the efforts of the Minerals Information Team, overseen by the Mineral Resources Program (MRP) of the U.S. Geological Survey

Mineral information and research are at least partially public goods. Once provided, many people and organizations can benefit without reducing other entities’ benefits, even if they do not pay for the information or research. As a result, there is a crucial role for the federal government to play in facilitating the provision of those types of information and research that are largely public, rather than private, in nature. Such provision can be facilitated directly by public agencies, or by universities, or by other nongovernmental organizations. SOURCE: NRC, 2003, pp. 24-28. |

(USGS). These mineral data are used widely both by a variety of private concerns and throughout the federal government. However, the committee recognizes a difference in federal definitions of “principal statistical agencies,” whose sole task it is to collect data and federal units such as the Minerals Information Team that are not designated principal statistical agencies but are nevertheless tasked to collect and disseminate data as a

part of other mandated duties. The committee suggests that this difference in definition can affect the strength of a given data collection program as a function of resource allocation and overall program visibility and autonomy and discusses these issues below.

Federal Statistical Programs and Data Collection

The policy of the federal government toward the data and statistics it collects and disseminates explicitly acknowledges the role that good statistics play in informed decision making by both public and private sectors. A recent example of the federal policy approach to statistics is excerpted from the 2008 executive budget proposal, under the heading “Strengthening Federal Statistics” (OMB, 2007a, Section 4, p. 37):

Federal statistical programs produce key information to inform public and private decision makers about a range of topics of interest, including the economy, the population, agriculture, crime, education, energy, the environment, health, science, and transportation. The ability of governments, businesses, and citizens to make appropriate decisions about budgets, employment, investments, taxes, and a host of other important matters depends critically on the ready availability of relevant, accurate, and timely Federal statistics.

The U.S. statistical programs are decentralized in nature. Of the more than 70 federal agencies or programs receiving funding to carry out statistical activities, only 13 are considered ‘principal’ federal statistical agencies and are members of the Interagency Council on Statistical Policy (ICSP). The other 60 or so agencies collect data in conjunction with other missions such as providing services or enforcing regulations. The 13 principal agencies follow (OMB, 2007a, Section 4, p. 38):

-

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Department of Commerce

-

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Department of Justice

-

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Department of Labor

-

Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Department of Transportation

-

Census Bureau, Department of Commerce

-

Energy Information Administration (EIA), Department of Energy

-

Economic Research Service, Department of Agriculture

-

National Agricultural Statistics Service, Department of Agriculture

-

National Center for Education Statistics, Department of Education

-

National Center for Health Statistics, Department of Health and Human Services

-

Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics, Social Security Administration

-

Statistics of Income, Internal Revenue Service, Department of the Treasury

-

Science Resources Statistics Division, National Science Foundation

These principal statistical agencies received approximately $2.2 billion in FY 2006, which is about 40 percent of the funding for all agencies collecting statistical data (estimated to be $5.4 billion for FY 2007; OMB, 2007b).

Agencies or programs that are solely and directly responsible for statistical data collection are more likely to be able to develop and maintain an efficient program focused on the types of data necessary to support their missions. This ability is particularly important in order to meet the ICSP performance standards that directly address whether the unit performing the collection of data and distribution of information is effective. Those performance standards are used in completing the administration’s Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART).

Conversely, federal units that have statistical data collection as only one feature of their body of tasks may not be able to maintain consistent resource levels and may lack broader federal program support necessary over the long term to achieve their data collection and dissemination goals or to maintain the important “effective” rating in PART. Furthermore,

when a data collection unit is not designated as principal, its mission may be diluted or made subordinate to the overall mission of the agency or department of which it is a part, particularly in situations of constrained resources. From the standpoint of collecting data and statistics on minerals, the committee finds it significant that none of the 13 principal statistical agencies collects and publishes annual data on minerals and their availability. As previous chapters have demonstrated, minerals are essential natural resources that are intrinsic to the availability and function of an enormous number of consumer goods in the nation and to the general national infrastructure.

Lacking somewhat the direct macroeconomic impact that energy has on the nation, minerals nonetheless factor into the overall function and productivity of the country. Critical minerals, in particular, may play very specific roles in the development of different industry sectors and their products. In this regard, the committee found a potential analogue for the concept of principal mineral statistical data collection through the example of the EIA. Box 5.2 reviews the history, purview, and federal role of the EIA, together with its impact on energy policy, due in part, in the committee’s view, to its status as a principal statistical agency.

Confidentiality of Federal Survey Information

An understanding of the role of data confidentiality in all federal data collection activities is important to acquire a fuller understanding of the basis for federal engagement in collecting data for policy formulation and implementation. Confidentiality of proprietary data by privately and publicly owned companies is considered to be a fundamental right, and for some a necessity, in a world economy subject to intense competition. Recent affirmation of the need to balance federal data collection with respect for privacy was put forward in the language of the 2008 executive budget proposal (OMB, 2007b, Section 4, p. 37):

As the collectors and providers of these basic statistics, the responsible agencies act as data stewards—balancing public and private

decision makers’ needs for information with legal and ethical obligations to minimize reporting burden, respect respondents’ privacy, and protect the confidentiality of the data provided to the Government.

The need to protect the confidentiality of data provided to the federal government and the need to respect respondents’ privacy suggests that the primary mineral data made available to the public (and indeed all fundamental data gathering) be largely conducted in an organized and accountable manner by federal government programs or agencies specifically tasked and qualified to do so; federal programs can collect such data in an unbiased way that ensures the anonymity of the respondents and subsequent use of the data for the public good. Collection of data by the government does not preclude their collection by various nongovernmental entities, including those who do so to satisfy a commercial need for data not collected by government. When nongovernmental entities do collect information, they usually do so in order to satisfy a specific constituency and not necessarily the needs of government to formulate and monitor public policy. Importantly also, even if confidentiality concerns could be guaranteed, the cost of thorough and accurate data collection at a national scale is high and may be excessive for a nongovernmental entity compared to the market value of the data.

The principle of data confidentiality adhered to by federal statistical agencies and programs is based on the belief that individuals and businesses will be more likely to give complete and factual answers to surveys when they are assured that their responses will not be used to bring legal or regulatory actions against them. In some instances, particularly where businesses are in highly competitive markets, respondents may fear that disclosure of certain business data to competitors or even customers will result in damage to their business. It is believed that businesses will be more likely to trust government agencies to maintain confidentiality than an association or other nongovernmental entity.

Finally, in terms of contrasting a strong governmental statistical role in collection of mineral or other data with the role played by nongovernmen-

|

BOX 5.2 Domestic Energy Information: An Analogue for Mineral Information Collection The oil embargo of 1973 and resulting fluctuations in the nation’s supply and price of oil prompted a congressional response in 1974 through passage of the Federal Energy Administration (FEA) Act. FEA was the first federal agency with a primary responsibility for energy issues, and a key FEA function was the collection, analysis, and dissemination of national and international energy information (U.S. Congress, 1974). As part of its energy information collection procedures, FEA was given data collection responsibility with related enforcement authority for its energy surveys of energy suppliers and major energy consumers. Energy data were to be used for statistical and forecasting activities and analyses such as the structure of the energy supply system, including resource consumption; energy resource reserves, exploration, development, production, transportation, and consumption sensitivities to economic factors, environmental constraints, technological improvements, and substitutability of alternate energy sources; and long-term industrial, labor, and regional impacts of changes in patterns of energy supply and consumption. In 1977, the Department of Energy (DOE) replaced the FEA as set forth in Public Law 95-91. The EIA was established as part of DOE to incorporate the information-gathering tasks and functions described for FEA, in addition to the responsibility “… for carrying out a central, comprehensive, and unified energy data and information program which will collect, evaluate, assemble, analyze, and disseminate data and information which is relevant to energy resource reserves, energy production, demand, and technology, and related economic and statistical information, or which is relevant to the adequacy of energy resources to meet the demands in the near and longer term future for the Nation’s economic and social needs” (U.S. Congress, 1977). The security of the nation’s energy supply was thus a concept embedded in this public charter. Although located within and working in close collaboration with DOE, the EIA maintains independence with regard to its work. This concept of independence is embodied in its enabling legislation, mandating that the EIA administrator “shall not be required to obtain the approval of any other officer or employee of the Department [of Energy] in connection with the collection or analysis of any information; nor shall the Administrator be required, prior to publication, to obtain the approval of any other officer or employee of the United States with respect to the substance of any statistical or forecasting technical reports which he [she] has prepared in accordance with law” (U.S. Congress, 1977). With a focus on gathering, analyzing, and forecasting energy information for the |

|

public and private sectors, the EIA’s four program offices cover oil and natural gas; coal, nuclear, electric, and alternate fuels; energy markets and end use; and integrated analysis and forecasting. Four support offices provide the assistance required for effective and efficient dissemination of energy information. EIA works to meet the needs of its congressional clients as well as other important customers including state and local governments, federal agencies, industry, and the general public. Particularly interesting to many clients is the product and service line that incorporates time series data based on EIA’s 65 recurring statistical surveys. Other EIA data sources include international information exchanges with individual countries or agencies such as the International Energy Agency. The relationship between the EIA, industry, and other public and private organizations is symbiotic: industry and other organizations rely on the data, analyses, and forecasts disseminated by EIA, and EIA relies on thorough and accurate information from these entities to amalgamate into its national energy information system. The interrelationships of energy, the economy, the environment, and the quality of life of U.S. citizens have led to significant increases in demands for EIA’s information. For example, since 2000 the need for petroleum information has increased as evidenced by greater public demand and inquiries, as well as congressional requests, for information. As a result, the EIA made a decision to elevate the quantity, frequency, and types of petroleum information available to the public. For example, “This Week in Petroleum,” available online at http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/oog/info/twip/twip.asp, was introduced in 2002 to improve public understanding of EIA’s petroleum data and the many factors affecting petroleum markets. In the committee’s parlance, oil is considered a critical fuel type by the EIA, and the amount and frequency of data collected for this fuel type were increased recently to satisfy public and private demands to plan for and react to potential fluctuations in the petroleum supply. Importantly, although greater need for information may dictate an increase in the frequency of data reporting for distinct fuel types, baseline data collection is always maintained on the other fuel types in EIA’s portfolio. Gaps are difficult or impossible to fill if data collection on a fuel type ceases. Furthermore, while baseline data are important all the time, baseline data collection is most important—yet most difficult—during times of crisis, underscoring the need to maintain good baseline data sources to weather any crisis period. As an independent, federal entity, EIA data are presented in an unbiased manner where statistical and quality standards are followed. Data breakdowns and presentations include full data sets at national levels, by sector or state, and by industry, as well as analyses and forecasts. EIA’s analyses and forecasts are interpretations or models of data, and these interpretations or models are only as credible or defensible as the data upon which |

|

they are based. Errors in any data presented by the EIA may result in inappropriate market responses. Industry cooperation in accurately completing data surveys is thus paramount to maintaining the quality of EIA’s data sets. Although industry has a very high rate of complying with its surveys, EIA benefits from the legally mandated collection enforcement authority it possesses, as well as the provisions it makes with regard to protecting sensitive information. The committee notes that recent legal proceedings surrounding the maintenance of data confidentiality in certain federal investigations have raised doubt about federal agencies’ ability to protect data sources in all situations (Anderson and Seltzer, 2005). Accurate and thorough data collection and analysis are time-consuming and expensive processes, and the EIA must continually demonstrate the benefit to the public of collecting the data. Interesting, useful, and timely data presentation with strong basis in effective dissemination is one of the keys to this public education process. |

tal entities that also collect such data, consideration must be given to the fact that free public data availability is a key feature of making informed policy decisions and of fulfilling a responsibility to the public served by the federal government. Despite comprehensive and often very useful statistical gathering, analysis, forecasting, and publications by nongovernmental entities, usually limited information is available free to the public from such sources simply because these entities must recover the cost of data collection and analysis; thus, more comprehensive data, analyses, forecasts, and publications are often available only on payment of a subscription fee. The federal government can and does purchase these subscriptions for specific purposes, but it must still collate and analyze the data and cannot always document the data sources or the degree of duplication between different data sets. Data purchase from private sources by the federal government is necessary and useful for a variety of purposes, but it is not considered adequate to serve identified public policy needs.

|

Current federal mineral data collection through the USGS Minerals Information Team follows many of the same basic procedures as does the EIA, particularly with regard to attempting to ensure accurate and timely mineral data collection and the general scope of its mandate, but with two important differences: (1) the Minerals Information Team is not a defined, principal statistical agency and as such is not autonomous either in function or in resource allocation from the Department of the Interior and USGS; and (2) though it does largely receive good cooperation from the private sector, the Minerals Information Team does not have collection enforcement authority for its surveys, nor did its predecessor, the U.S. Bureau of Mines. SOURCE: EIA, 2006; DeYoung (2007); M. Kaas, personal communication, June 2007; J. Shore, personal communication, March 2007. |

CRITICAL MINERAL INFORMATION SOURCES

Information about minerals produced and used in the United States is available from a wide variety of public sources and nonprofit or for-profit organizations. These sources are based both in this country and abroad. In this section the committee describes some of these information sources, with the caveat that the list is by no means exhaustive.

Many mineral data sources generate limited information or produce data on an ad hoc basis, rather than as part of a regularly scheduled program. Doctoral and master’s theses and other academic and trade publications can contain valuable data and insightful analysis, but distribution is often limited and may not be timely (too early or too late) to be useful in determining criticality, so these sources are not discussed further here. In addition, numerous organizations have Internet web sites dedicated to providing information either in support of or against mining and its effects on the environment and local communities; despite the potential for bias, these sites often can present valuable information to assist in developing

appropriate policy responses to address critical minerals, but again these sources were not considered in the committee’s analysis because of the difficulty in documenting the background protocol used to collect and collate the data.

The committee examined numerous international government data sources, domestic and international nongovernmental data sources, and U.S. federal data sources of mineral information (see also Table 5.1). Of the international government organizations collecting such data, geological surveys are often rich sources of mineral information. The information is often focused on the survey’s home nation, but very often these databases may provide international data as well. As one example, Box 5.3 provides a description of the Japanese Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) and the role it plays in data gathering, analysis, and information dissemination in a nation that is heavily dependent on imports for its minerals. The committee found that almost all nations, and sometimes associations of nations, have mineral information in one form or another, but the quality and quantity of the data and their presentation and accessibility are highly variable. The committee notes that not all foreign geological surveys allow free public access to their assembled data sets.

Numerous private organizations collect and sell mineral data and related reports targeted to specific business needs. Information from these sources has the potential to fill gaps that exist in government statistical products, analyses, and forecasts. Additional information is available from nongovernmental professional associations and organizations that collect data about their respective industries and make some data available to the public or to subscribers or members on a fee basis. Nearly every major metal and many minerals are represented by one or more dedicated professional associations, all of which seek to provide market information to their constituencies and the public. The committee does note these information sources as potentially very useful supplemental sources of specific information on single minerals or specific groups of minerals. They carry with them, however, the difficulty in documenting data sources, data collection protocol, and potential overlap with other data sets from competing

TABLE 5.1 International and Domestic Sources of Mineral information

|

Classification |

Name |

Internet Sites |

|

International |

British Geological Survey |

|

|

|

Natural Resources Canada |

|

|

|

Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization |

|

|

|

Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières |

|

|

|

Japanese Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation |

|

|

|

Eurostat |

|

|

|

Mineral Resources Forum of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development |

|

Classification |

Name |

Internet Sites |

|

Private and nongovernmental |

Port Import Export Reporting Service |

|

|

Metals Economics Group |

||

|

|

Johnson Matthey |

|

|

|

National Mining Association |

|

|

|

Portland Cement Association |

|

|

|

Aluminum Association, Inc. |

|

|

|

Copper Development Association |

|

|

|

Nickel Institute |

|

|

|

American Iron and Steel Institute |

|

|

|

Great Western Minerals Group, Limited |

|

|

|

Minerals Information Institute |

|

|

|

International Copper Study Group |

|

|

|

International Nickel Study Group |

|

|

|

International Lead And Zinc Study Group |

|

U.S. federal |

Minerals Information Team of the USGS Mineral Resources Program |

|

|

|

Department of Commerce, U.S. Bureau of the Census |

|

|

|

Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) |

|

|

|

Department of Labor, International Trade Administration |

|

|

|

Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) |

|

|

|

Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration |

|

|

|

Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management |

|

|

|

Department of the Interior, Office of Surface Mining |

|

|

|

Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service |

|

|

|

Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service |

|

|

|

Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health |

|

|

|

Department of Defense, National Defense Stockpile |

|

BOX 5.3 Japanese Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation Japanese industry is highly reliant on imported minerals and mineral products. The Japanese government, for a number of years, has undertaken activities to facilitate stable supplies. In 2004, it established the Japanese Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) to undertake these activities, integrating activities previously carried out in the Japan National Oil Corporation (since 1967) and the Metal Mining Agency of Japan (since 1963). JOGMEC is responsible for oil, natural gas, and metals and minerals. For metals and minerals, among JOGMEC’s important activities are providing financial assistance to Japanese companies for mineral exploration and deposit development, gathering and analyzing information on mineral and metal markets to better understand supply risk, and managing Japan’s economic stockpile for rare metals. JOGMEC defines rare metals as those that (1) are essential to Japanese industry—sectors such as iron and steel, automobiles, information technology, and home appliances—and (2) are subject to significant supply instability. JOGMEC gathers, analyzes, and disseminates information to assist Japanese companies and government agencies. Types of data and information include overseas geology and ore deposit descriptions and interpretations, mineral policies and regulations for other nations, market data and analysis (supply, demand, prices, etc.), and information on mining and the environment. JOGMEC manages rare metal stockpiles in cooperation with private companies. The goal is to have stocks equivalent to 60 days of Japanese industrial consumption—42 held by JOGMEC and 18 by private Japanese companies. At present, stocks exist for seven metals: chromium, cobalt, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, tungsten, and vanadium. JOGMEC is closely observing seven other metals or groups of metals: gallium, indium, niobium, platinum, rare earths, strontium, and tantalum. A set of guidelines and rules govern release of metals from stocks. In 2005, the stockpile released nickel and tungsten to the market. NOTE: Chapter 4 evaluates 8 of the 14 metals JOGMEC either stockpiles or is evaluating closely. Stated slightly differently, 8 of the 11 minerals evaluated in Chapter 4 are being stockpiled or monitored by JOGMEC. SOURCE: JOGMEC, available online at http://www.jogmec.go.jp (accessed June 21, 2007); Murakami, 2007. |

associations or private organizations. For many of these data assemblages, a collating and analysis activity is required if the data are to be of maximum utility. This activity is scarce or absent within the federal government at present.

For the federal government, the Bureau of the Census of the Department of Commerce conducts a Census of the Mineral Industries every 5 years, for years ending in 2 and 7. All domestic mining establishments with at least one employee are surveyed. The content of the census includes the kind of business, geographic location, legal form of ownership, total revenue, annual and first-quarter payroll, and number of employees for the pay period including March 12. Receipt of a “long form” requires the establishment to provide added detail on employment, payrolls, worker hours and payroll supplements, value of shipments, inventories, capital expenditures, and quantity and value of products, supplies, and fuels. A short form requests only basic data in the form of capital expenditures and quantity and value of products.

While participation in the census is mandatory, the data collected provide a limited picture of specific minerals due both to reports that withhold information to avoid revealing confidential data and to the aggregation of categories. The data categories are useful for providing input to national income and product accounts, but the types of data collected are insufficient for detailed life-cycle analysis or for determining criticality because information on production and consumption of most mineral products is not collected or reported.

The Department of Commerce BEA and International Trade Administration are important users, rather than collectors, of mineral data in the conduct of their policy discussions and in assessing the effects of trade, tariff, and nontariff barriers, regulation, licensing schemes, and international competition on the function of commerce in the United States (Cammarota, 2007). In the federal structure, these agencies’ policies are supported by the data and information they are able to collate from other sources. For mineral information, the Department of Commerce relies heavily on the USGS Minerals Information Team, but also uses other data sources, including information from federal study groups and industry

associations. Disaggregated mineral data were noted as a preference for the Department of Commerce whenever possible.

Mineral information is also collected by other government agencies on a basis that is usually quite specific to the mission of the agency or a defined, finite project or task. Examples are the Bureau of Land Management, the Mine Safety and Health Administration, the Office of Surface Mining, the Minerals Management Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Department of Defense (DoD) National Defense Stockpile. Because the data are usually collected for a specific purpose, they are often not made easily available to the public and may not be published in a form that allows simple comparison with data from other government sources.

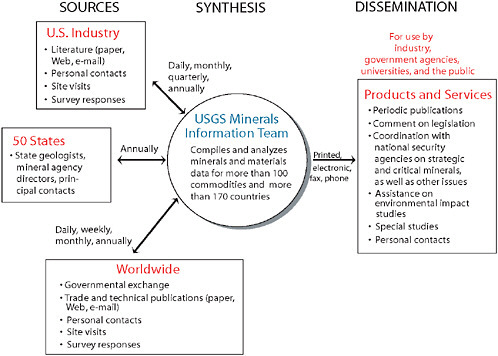

The most comprehensive source of mineral information for the United States is the Minerals Information Team of the USGS MRP (Figure 5.1). The Minerals Information Team is the sole agency within the federal government tasked to “collect, analyze, and disseminate information on the domestic and international supply of and demand for minerals and mineral materials essential to the U.S. economy and national security” (USGS, 2007). In addition to traditional mineral production data, Minerals Information Team analyses include some amount of information and reports on mineral conservation, sustainability, material flows, availability, and the economic health of the U.S. mineral industry.

To produce its assessments and reports, the group requests data on mineral production, consumption, recycling, stocks, and shipments from the mining and mineral processing industries in the United States; more than 140 surveys are conducted annually on commodities. Aggregated U.S. statistics are published to preserve proprietary company data. The Minerals Information Team does not have enforcement authority with these industry surveys (see also Box 5.1). Other data include those collected annually from more than 18,000 voluntary producer and consumer establishments that complete about 40,000 survey forms. The USGS also has cooperative agreements with state governments to exchange data. Data from other federal agencies, primarily the Department of Commerce, are also included in the analyses.

FIGURE 5.1 Diagram showing the main activities, data sources, partnerships, and work flow for the USGS Minerals Information Team. SOURCE: USGS, 2007.

The Minerals Information Team’s customers include the general public, Congress, industry, and other federal agencies, including the Department of Commerce, the DoD National Defense Stockpile, the Federal Reserve Board, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Environmental Protection Agency. The committee was struck by the uniform responses it received from industry, government, and academic participants at its open meeting sessions (Appendix B) and in voluntary written contributions to its work (e.g., Ellis, 2007) that USGS Minerals Information Team data were the primary data to which they turned for immediate information on minerals in their respective fields. Nonetheless, the Minerals Information Team activities are not as comprehensive as is desirable. Reflecting the history and focus of the parent agency, Minerals

Information Team analyses do not regularly address in-use stocks of metals, scrap stock and trade, detailed recycling information, and other aspects of mineral availability and criticality centered on stages of the material life cycle well removed from mineral extraction and processing.

ENHANCING OUR UNDERSTANDING OF CRITICAL MINERALS: FEDERAL INFORMATION AND RESEARCH NEEDS

The Mineral Cycle, Federal Information Exchange, and Research

As previous chapters have demonstrated, minerals are rarely used in their raw form as an end product. They are incorporated into an intermediate or final product that takes advantage of the properties of the particular mineral to improve the performance of the final application. For that reason it is not enough to have information only about the primary production of the mineral. As outlined in Chapter 1, the entire life cycle of the mineral is important because it directly affects the supply-demand relationship. If markets function well, the price mechanism will bring about adjustments in the supply-demand relationship that will restore the balance over time. If the market mechanism is to function properly it is absolutely essential that the market have good information about both sides of the equation. Good information about all stages of the life cycle of the mineral becomes increasingly important if markets are not completely well functioning—for example, if significant environmental damage accompanies production or if innovative research is an important determinant of long-term mineral availability.

The USGS MRP, which has oversight of the Minerals Information Team, is the only federal program that provides resource assessments and research on mineral potential, production, consumption, and environmental impacts. The committee is supportive of the incorporation of critical minerals as a specific piece of this type of mineral life-cycle analysis by the MRP and the Minerals Information Team and by other federal agencies collecting mineral-related data.

The most recent attempt by Congress to ensure that all federal statistical agencies would be able to protect the confidentiality of data collected by them is the 2002 Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act (CIPSEA). In addition to data confidentiality, other provisions in CIPSEA are also important with respect to improvement in all federal data collection. CIPSEA legislation has provisions intended “to promote efficiency in the production of the nation’s statistics by authorizing limited sharing of business data for statistical purposes. The objectives behind the data-sharing component of the legislation are threefold. First, it was hoped that permitting the three agencies (Census Bureau, BEA, and BLS) to share information would improve the comparability and accuracy of federal statistics by allowing timelier updates of sample frames, development of consistent classifications of establishments and industries, and exploitation of administrative data. Second, more integrated use of data should reduce the paperwork burden for surveyed businesses. Finally, through these mechanisms, it was hoped that the sharing of data would lead to improved understanding of the U.S. economy, especially for key industry and regional statistics” (NRC, 2006). The committee agrees that sharing statistics and the survey lists used to collect data will lead to better, more complete information and will minimize duplication of data sets, facilitating overall improvement in federal mineral and economic analysis. At present, the Minerals Information Team is not officially included in the sharing of survey lists, so it is difficult to compare and collate data collected and published by the Census Bureau, the BLS, or the BEA with data collected and published by the Minerals Information Team.

To develop a good understanding of both the criticality and the complete life cycle of one or more minerals, information collected in the following areas, in addition to the standard primary production and demand for each mineral, could be useful:

-

Recycling or scrap generation and inventories of old scrap

-

In-use stocks

-

Reserves and resources

-

Downstream uses

-

Subeconomic resources

-

Material flows

-

International information in all of the above areas

There currently is no source of information that supplies all of the above data on at least an annual basis for all minerals.

In a number of areas relevant to critical materials, the committee found that there was a paucity of information or that appropriate technology had not been developed or pushed very far. The committee relates these deficiencies to a low level of support for research on resource availability and resource technology. In particular, the following topics require substantially increased research effort if critical materials are to be identified reliably in the future, the sources of those materials (from both virgin and recyclable stocks) are to be better quantified, and the technology for extraction and processing is to be substantially enhanced:

-

Theoretical geochemical research to better identify and quantify virgin stocks that are potentially minable;

-

Extraction and processing technology to improve energy efficiency, decrease water use, and enhance material separation;

-

Remanufacturing and recycling technology, which is the key component in increasing the rate and efficiency of material reuse; and

-

The characterization of stocks and flows of materials, especially import and export, as components of products, and losses upon product discard. This lack of information impedes planning on many levels.

A Federal Model to Address Critical Minerals as Part of Public Policy

Once mineral criticality has been established, the question arises as to what public policy actions could circumvent or eliminate the factors that have brought about the critical nature of the mineral. The Industrial College of the Armed Forces (ICAF) National Defense University issued a report on strategic materials in 2006 that addressed the question of what public

policy ought to do toward ensuring the availability of strategic minerals (ICAF, 2006). The public policy issues are similar for both strategic minerals and critical minerals, and the committee finds the ICAF analysis to be a structured and pragmatic way to view critical mineral data collection and organization. A brief review of this analysis is offered here as one potential, published, federally oriented perspective by which a federal mineral information collection and research program could be enhanced and strengthened to address critical minerals. The military is clearly only one of the many customers for mineral information, and its suggested approach has practical merits.

Among the general findings in the analysis, two are especially relevant and applicable to critical minerals. First, the report stated that “more effective collaboration between industry, government and academia could improve the industry’s ability to cope” (ICAF, 2006, p. 20) with the various challenges facing suppliers of strategic materials. As an example, the study refers to the potential for collaboration to streamline legislative, regulatory, and policy issues. Second, the report stated that “increased support for education and research throughout American society would provide for continued innovation in materials science” (ICAF, 2006, p. 20).

The report also contains a number of specific findings organized around strategic materials at different stages in the product life cycle. At the mature stage, the report suggests that materials typically are subject to increased international competition and that companies primarily pursue strategies aimed at operational efficiency and low costs. The report cites steel and aluminum as examples. The report also argues that it is important for governments to avoid inappropriate protection for mature industries, except in exceptionally limited and compelling circumstances.

For materials experiencing significant growth, on the other hand, key challenges are gaining access to raw materials when demand is increasing rapidly and facilitating rapid transfer of new technologies. The report cites advanced composites, superalloys, and specialized materials using rare earth elements as examples (ICAF, 2006). A key role for government here is in facilitating and enabling technology transitions and in monitoring markets for these growth materials for potential supply restrictions. The recom-

mended role of government regarding minerals in growth markets reflects the fact that many materials in new technological applications have come about through government involvement in research and development to achieve higher performance in new applications. Oftentimes military use alone is insufficient to achieve economic viability of a material without commercial applications as well. Government therefore needs to foster applications that will improve the commercial success of the material in order to ensure its availability at reasonable cost for military applications. One focus in this report has been to put into place a framework for determining mineral criticality, some of which are in a growth phase of development according to definitions presented in the ICAF (2006) report.

Finally, the report argues that government’s most significant role relates to breakthrough materials requiring significant research and development that is high risk and has uncertain rewards. As examples of breakthrough technologies and materials, it cites nanotechnologies, micro-electromechanical systems, and biometrics. The “ventures in breakthrough technologies face development difficulties that require substantial R&D and engineering. Within the materials industry, specific problems include long development cycles, low levels of funding, stakeholder concerns, and foreign competition. Overcoming these challenges merits greater government attention than typically required for more mature materials markets” (ICAF, 2006, p. 10).

The ICAF report recommended that the role of government regarding minerals in breakthrough markets should be to provide active support for the development of the next generation of materials. Experts in the materials field view DoD as a key federal organization to coordinate and fund materials research, recommending additional research into the discovery and characterization of materials with unique or substantially improved properties (NRC, 2003). Defense leaders acknowledge this key role because “many emerging defense suppliers find it difficult to raise funds for military R&D and project opportunities” (DUSD(IP), 2003, p. B-8). While many stakeholders would welcome increased funding for advanced materials research, a fiscally responsible initial step could prioritize

materials research endeavors to ensure that the nation’s most important requirements are met.

Many government efforts specifically focus on innovative research in materials specialties. These efforts support a variety of worthwhile research in materials science. However, individual agencies award many of these grants on an individual or somewhat ad hoc basis that is not the product of a coordinated research strategy. In particular, they rarely address mineral information needs or consider mineral supply and demand data or criticality, either short or long term.

The ICAF (2006) study is silent about the important question regarding the source or sources from which the information will come to conduct the recommended analysis and support the resulting mineral cycle categorization. Studies going back many years have repeatedly made the case for a federally supported and funded program to collect and disseminate the mineral data necessary to make good policy decisions. The committee views materials research as an integrated part of the support for and use of high-quality mineral information and research; indeed, materials and mineral research complement one another, with mineral research and data collection providing information for breakthroughs in new materials; these breakthroughs provide new paths along which to view the dynamics of mineral criticality.

THE PROFESSIONAL PIPELINE

Highlighting the need for an innovative and educated workforce to ensure the nation’s continued growth and prosperity, the NRC (2007) report Rising Above the Gathering Storm drew attention to the decreasing number of students being educated in all science and engineering fields in the United States and raised questions about the potential detrimental effect of this trend on future domestic technological innovation, manufacturing productivity, and general economic well-being. Coupled with demographic trends that show a large, aging workforce and a disproportionately smaller number of younger persons able to replace these professionals as they retire (The Economist, 2006), the ability of the nation to respond to surges in demand

for qualified workers in industry, the federal government, and educational fields is suggested to be hampered if changes are not enacted in the national approach toward science and engineering education at all levels.

While the demographic issue is a global phenomenon, mineral availability over the longer term—in terms of both quantity and quality of resources—as discussed in this report depends importantly on specific types of resource professionals. More specifically, well-educated resource professionals are essential in industry, the federal government, and academic institutions for fostering the innovation that is necessary to ensure the availability of critical mineral resources at acceptable costs and with minimal environmental damage. These professionals include persons trained in what may be considered the more traditional fields of economic geology, mining engineering, and mineral processing engineering as well as persons in related specialties of resource analysis, resource economics, and environmental engineering. In the most recent decade, realization of the existence and magnitude of secondary resources in potentially recycled materials has added a need for two types of specialists not heretofore recognized or supported: product design engineers specializing in “design for recycling” and recycling technology engineers. By and large, only a handful of these “end-of-life” specialists exist worldwide, and those who exist were trained on the job rather than in dedicated academic programs.

With the collapse of the job market for undergraduate and graduate students in the 1980s and 1990s in fields related to the mineral engineering disciplines, schools and programs in these fields have disappeared relatively quickly. In addition to the lack of mineral and mining engineers in training at universities and colleges, very few formal training programs exist in materials recycling technology. While a number of highly qualified graduates in the general engineering disciplines, including environmental engineering, are being employed and making strong contributions to the mineral and mining industry, the skills and training for specific types of work in mining engineering, mineral economics, metallurgy, and recycling, for example, are not necessarily easily transferred, and on-the-job retraining between disciplines can be very demanding in terms of resources and time.

The private sector has underscored the need now for new graduates and midcareer persons with mining, geoscience, and/or engineering backgrounds to fill open positions in its organizations in all areas of research, exploration, production, health and safety, and environmental regulation and compliance (e.g., LeVier, 2007). Implicit in this report with regard to critical minerals is the added need to maintain adequate, accurate, and timely information and analysis on minerals at a national level in the federal government with additional, not fewer, professionals having appropriate backgrounds to perform the work. The committee did not conduct a formal survey of numbers of professionals with mineral- or material-related expertise in all federal agencies. Statistics available from the National Science Foundation (NSF, 2005) on the general employment trends in science and engineering in the federal government between the years 1998 and 2002 indicate that in the fields of geology, geophysics, mining engineering, metallurgy, or more generally natural resource operations, the number of federal employees stayed roughly the same in all fields except metallurgy and mining engineering. In the latter two fields, a slight decrease was recorded across the entire federal government. These statistics did not provide, and were not designed to provide, a detailed breakdown within specific departments or offices of each agency, nor did they provide an indication of the types of work the individuals in these fields perform or their age demographic. The committee thus acknowledges and views with concern the lack of supply of persons with appropriate backgrounds in mineral- and material-related fields noted during the course of this study in discussions with the DoD, Department of Commerce, and Department of the Interior.

For example, several years ago the Department of Commerce standardized all of its position descriptions within its industry offices. The department made a concerted effort to hire “generalists” who could easily be assigned to several industries or reassigned between industries. As a result, specific industry experience or expertise was eliminated. In addition, specific industry coverage was reduced: during the past 20 years the Department of Commerce eliminated the Copper, Lead/Zinc, Aluminum, Steel, and Miscellaneous Metals Divisions. These divisions were combined

into one Metals Division. Currently only four individuals are responsible for issues affecting metallic raw materials.

Historically also, the U.S. Bureau of Mines (USBM), because of its mandate, had the highest concentration of mining-related professionals in the federal government. At one point, more than 1000 individuals, including project and support staff, were employed at the USBM. The closing of USBM in 1995 curtailed or terminated much of the government’s research activities related to mineral resources (M. Kaas, personal communication, March 2007), although data acquisition and dissemination remains as a high-quality but (the committee believes) underfunded program now at the Minerals Information Team within the USGS. Natural attrition and funding issues such as these, as well as administrative decisions on the part of the U.S. government, have compounded the existing demographic trend for groups like the Minerals Information Team. The organization has seen a decrease in staff levels of 29 percent since 1996, including a variety of mineral specialists, some of whom also contribute language interpretation skills for international mineral data in their global analyses. Thus, while the U.S. government is itself, to a large degree, responsible for its current staffing situation regarding mineral-related professionals, the fact that numerous federal agencies collect, use, and analyze mineral and mineral economic data, conduct mineral-related leasing or regulatory activities, work in mining engineering and mine safety projects, or perform mineral- and material-related research and analysis suggests that the number of professionals in these fields has to be maintained or increased, not reduced, as natural attrition through retirement begins to take place given the demographics at these agencies.

Although it is tempting to extrapolate these observations to private industry and academic sectors, as outlined more generally in the National Research Council report (2007), the committee did not have the time or purview to establish labor and training statistics in all mineral-related fields across the private, public, and academic sectors to make a broader statement, and that work is left for another study to assess in detail. However, the committee would urge that implementing the conclusions and recommendations of this study occur simultaneously with examination

of the workforce situation, including the appropriate number and skills of professionals needed and available to conduct effective work related to information gathering and research on critical minerals in a global, material-flow framework.

The committee’s opinion is that present student levels and retirement trends at universities in several key mineral-related fields question the capacity to meet future workforce requirements. Market responses may eventually cover some of the apparent gap between demand for workers, and the supply of new hires to fill open positions in mineral-related fields, but the time lag between the beginning of the market response and the actual entry of educated and trained persons into these positions entails larger commitments than the market alone is able to address.

SUMMARY AND FINDINGS

This chapter has provided past legislative and executive references that have demonstrated support for comprehensive federal data collection as an integral part of both national policy and, specifically, national mineral policy. In its examination of federal statistical programs, the committee has found that while the total federal commitment to data collection is evident, the detail and depth to which a statistical agency or program can collect and disseminate accurate and timely data may depend on the agency or program’s autonomy, the resources it is allocated as a function of that autonomy, and the authority with which it is allowed to enforce collection of survey data. Federal mineral data collection does not currently have the same authority given to designated federal statistical agencies and, by that omission, may lack some of the authority this committee finds to be appropriate for the important task of collecting mineral information and its incorporation in decision making that affects the U.S. economy. In its functions and legislated authority, the EIA is provided as a potential example by which current federal minerals information collection could be strengthened and made more effective; this includes enforcement authority for mineral survey responses and the autonomy to make professional decisions regarding publication style and frequency for critical minerals.

In terms of sources for mineral data, information, and analysis, a large range of international, private, nongovernmental, and federal organizations or programs currently collect and disseminate such information at various levels. Both domestically and internationally, the committee did not find a more comprehensive source for mineral information today than the Minerals Information Team of the USGS. In view of the need to examine and determine mineral criticality within the framework of the complete mineral life cycle, the committee also suggests several additional types of mineral information that could be collected by the federal government and some research avenues that would be helpful to pursue in support of this type of data collection.

The committee found further:

-

Fully federally supported mineral information collection and research is needed by the public and private sectors to ensure unbiased and thorough reporting of available data.

-

Accurate and timely mineral information with regard to factors affecting mineral availability in the short, medium, and long term is important to guide policy.

-

Mineral information collection and research in the federal government is less robust than it could be, in part because the minerals data collection program of the Minerals Information Team does not have the status of a principal statistical agency.

-

Many similarities exist between the function and form of the EIA and the Minerals Information Team, with the exception of the status of the EIA as a principal statistical agency with survey enforcement authority and organizational autonomy.

-

Many international, private, nongovernmental, and federal government organizations, associations, and agencies supply various types of mineral information to the public, some for a fee. In the United States, the committee found unanimous agreement from private, academic, and federal professionals that the USGS Minerals Information Team is the premier source of mineral information, but that the quantity and depth of data have been reduced in recent years.

-

Full information on the mineral life cycle, and the critical mineral cycle particularly, requires information on recycling and scrap generation and inventories of old scrap; in-use stocks; reserves and resources; downstream uses; subeconomic resources; material flows; and international information in each of these areas. Federal mineral information collection presently does not include these factors.

-

Support of critical mineral information collection includes enhanced research in such areas as theoretical geochemical research, extraction and processing technology, remanufacturing and recycling technology, and stocks and flows of materials.

-

Formal coordination and data exchange between federal agencies collecting mineral information is an objective to reduce redundancy and ensure transparency but is not currently fully effective.

-

A potential model for the collection of mineral information is described in the ICAF report, which suggests a mineral “life-cycle” approach that offers specific challenges to the mineral sector and requires flexible federal approaches to mineral policy at various stages of the cycle, based on consistent mineral data collection.

-

With respect to the professional pipeline of training to carry out the data gathering, analysis, research, and exploration needed to evaluate minerals and their criticality, industry, the government, and educational institutions face an existing and growing shortage of resource professionals entering the system.

REFERENCES

Anderson, M., and W. Seltzer, 2005. Federal statistical confidentiality and business data: Twentieth century challenges and continuing issues. Paper prepared for the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, New York, March 30.

Cammarota, D., 2007. Presentation to the Committee on Critical Mineral Impacts on the U.S. Economy. Washington, D.C., March 8.

DeYoung, J. 2007. Presentation to the Committee on Critical Mineral Impacts on the U.S. Economy. Washington, D.C., March 8.

DUSD(IP) (Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Industrial Policy), 2003. Transforming the Defense Industrial Base: A Roadmap. Available online at http://www.acq.osd.mil/ip/docs/transforming_the_defense_ind_base-report_only.pdf (accessed May 22, 2006).

The Economist, 2006. Special Report: The ageing workforce. February 18:65-67.

EIA (Energy Information Administration), 2006. Overview of the Energy Information Administration’s National Energy Information System. Prepared in support of “Challenges, Choices, Changes: An External Study of the Energy Information Administration,” unpublished final report. Washington, D.C.

Ellis, M., 2007. Comment from the Industrial Minerals Association—North America, submitted to the committee, May 11. On file at the National Academies Public Access Records Office.

ICAF (Industrial College of the Armed Forces), 2006. AY 2005-2006 Industry Study Final Report: Strategic Materials. Washington D.C.: National Defense University. 30 pp. Available online at http://www.ndu.edu/icaf/industry/reports/2006/pdf/2006_STRATEGIC_MATERIALS.pdf (accessed June 27, 2007).

LeVier, M., 2007. Presentation to the Committee on Critical Mineral Impacts on the U.S. Economy (teleconference). Washington, D.C., March 8.

Murakami, S., 2007. Presentation to the Committee on Critical Mineral Impacts on the U.S. Economy. Washington, D.C., March 8.

NRC (National Research Council), 2003. Future Challenges for the U.S. Geological Survey’s Mineral Resources Program. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 139 pp.

NRC, 2006. Improving Business Statistics Through Interagency Data Sharing: Summary of a Workshop. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 156 pp.

NRC, 2007. Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 592 pp.

NSF (National Science Foundation), 2005. Federal Scientists and Engineers 1998-2002: Detailed Statistical Tables. Available online at http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf05304/pdf/nsf05304.pdf (accessed September 2007).

OMB (Office of Management and Budget), 2007a. Strengthening Federal Statistics. Available online at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/inforeg/statpolicy/strengthening_fed_stats_fy2008.pdf (accessed November 14, 2007).

OMB, 2007b. Statistical Programs of the United States Government Fiscal Year 2007. Washington, D.C.: Executive Office of the President. Available online at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/inforeg/07statprog.pdf (accessed July 18, 2007).

Shanks, W., 1983. Cameron Volume on Unconventional Mineral Deposits. Society of Economic Geologists, Society of Mining Engineers, American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers, 246 pp.

U.S. Congress, House, 1974. Federal Energy Administration (FEA) Act. H.R. 11793. 93rd Congress. Public Law 93-275. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Congress, Senate, 1977. Department of Energy Organization Act. S.Doc. 826. 95th Congress. Public Law 95-91. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Congress, House, 1980. U.S. Minerals Vulnerability: National Policy Implications, A Report of the Subcommittee on Mines and Mining of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. 96th Congress, 2nd Session.

USGS (U.S. Geological Survey), 2007. Mineral Information Team Information Handout. Available online at http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/mit/mit.pdf (accessed July 3, 2007).