7

Organizing the Research Community for Change

INTRODUCTION

In the context of a compelling, and rapidly growing, need for better approaches to develop and apply evidence about the comparative effectiveness of healthcare choices, the workshop Redesigning the Clinical Effectiveness Research Paradigm: Innovation and Practice-Based Approaches explored opportunities presented by emerging research networks and data resources, innovative study designs, and new methods of analysis and modeling that might help to address the evidence gaps. Participants in the meeting examined broadly the role of innovative research designs and tools that can expedite the development of evidence on clinical effectiveness by streamlining approaches and bringing research and practice closer together.

Comments throughout the workshop also highlighted system fragmentation and misaligned incentives that limit capacity to conduct timely research that addresses practical clinical questions. Cross-discipline and cross-sector work was emphasized as essential to shaping and supporting the development of an efficient and robust clinical effectiveness research enterprise. Ensuring research that focuses on producing evidence for physicians, patients, and policy makers; draws upon expertise from many different disciplines and fields (e.g., clinical trialists, epidemiologists, and health services and outcomes researchers); and functions to capture, extend, and apply learnings throughout an intervention’s lifecycle (e.g., development, approval, postmarket refinement) will require reevaluation and adjustment to many facets of the existing research enterprise (e.g., emphasis on post-

market evaluations in broad populations as well as approval studies, cross-disciplinary education and training, alignment of policy goals with funding, publication and career advancement opportunities, improved linkages with healthcare delivery systems).

The final workshop sessions were dedicated to discussion of how the research community might be organized, mobilized, and supported to effect broad changes needed. Common themes and follow-up opportunities for the Roundtable, noted throughout the discussion are also summarized here.1

INCREASING KNOWLEDGE FROM PRACTICE-BASED RESEARCH

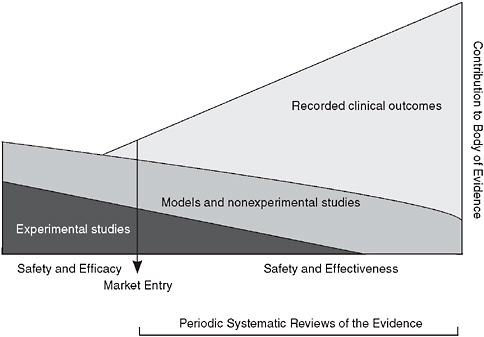

The multifaceted, practice-oriented approach to clinical effectiveness research discussed at the workshop complements and blends with traditional trial-oriented clinical research and may be represented as a continuum in which evidence is continuously produced by a blend of experimental studies with patient assignment (clinical trials); modeling, statistical, and observational studies without patient assignment; and monitored clinical experience (see Figure 7-1).

The ratio of the various approaches will vary with the nature of the intervention, as does the weight given to the available studies. This enhanced flexibility and range of research resources is facilitated by the development of innovative study design and analytic tools, and by the growing potential of electronic health records to allow much broader structure access to the results of the clinical experience. The ability to draw on real-time clinical insights will naturally improve over time.

The research community will play a vital role in developing a clinical effectiveness research enterprise that provides timely, reliable information that can be used in clinical decision making. Discussions throughout the workshop not only highlighted current shortfalls in the quality, quantity, and efficiency of this current research, but also explored many opportunities to develop incentives for the changes needed and to support those changes once they have been implemented. As reviewed in previous chapters, many elements are being developed and used to ensure research can be used more effectively to make evidence-based decisions in a clinical setting. These elements include innovative tools, techniques, and strategies that improve the efficiency and reliability of study methodologies; vastly larger and clinically richer datasets; and advances in information technology that will connect researchers and information, thus enabling studies not possible before. In some respects the largest challenge is engaging the research community

FIGURE 7-1 Evidence development in the learning healthcare system.

in efforts to resolve key technical and policy challenges, including removing barriers to coordination and implementation of research and research results. For example, improved understanding is needed of when and how the various methods are best applied to different research questions and which measures will improve study validation and reporting. Standardization of data and other efforts to improve data utility through coordination and linkage, as well as attention to issues related to data transparency and privacy or proprietary concerns are also priority areas. Because these issues often span disciplines and healthcare sectors, participants in the last session of the workshop were asked to suggest opportunities to foster the collaboration needed across the public and private sectors to drive change.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR ACTION

Mark B. McClellan, Brookings Institution;

Alan M. Krensky, National Institutes of Health;

Garry Neil, Johnson & Johnson;

John Niederhuber, National Cancer Institute;

Lewis Sandy, United Health Care

The five panelists opened the final workshop session by discussing some key needs and opportunities for the future of clinical effectiveness research.

They explored guiding principles for the research community; opportunities to use a lifecycle approach to help clinical research evolve into evidence development; and infrastructure needs and key challenges. To sharpen the focus on immediate opportunities, participants were asked to suggest activities that could be started in the next 12–18 months, in the absence of new legislation, funding, or creation of a central coordinating capacity. Following are summaries of comments from the panel and the subsequent open discussion.

Guiding Principles

Several panelists commented on the dramatic potential of the emerging era of research to accelerate the transfer of knowledge between basic research and clinical practice. Recent advances in genetics and genomics mark the “beginning of the beginning,” with the past decade of research providing a rich catalog of information that potentially can be translated into interventions with clinical use. Taking advantage of such opportunity will require the current system of clinical research—in use for the past 50 years—to evolve into one that makes better use of the power of technology to gather and use data to improve patient care and outcomes. As the pace of research and product development accelerates, the creation of systems to help track the effects of these agents in real time will be especially important. Guiding such dramatic reform will require a clarification of the mission, focus, and approaches to clinical effectiveness research and a greater emphasis on supporting innovation.

Clarify the Mission and Focus of Clinical Effectiveness Research

The fundamental mission of research is to help patients, yet there has been a detectable shift away from this basic tenet, as research organizations focus more on economics and less on impacting health outcomes. The identification of priority areas for research presents the opportunity to force greater focus on key issues, and a clear prioritization approach to identify issues with the greatest impact on the nation’s health and healthcare system would help decision makers to allocate limited resources more effectively (e.g., where limited evidence exists and there is high variability in practice; high costs and growth potential; or large populations are affected).

Along with the development of strategic initiatives to identify and address evidence gaps, consideration is needed on how to establish appropriate evaluation components. Developing metrics not only will help to track progress but also will illustrate the impact of focused research efforts. Demonstrating that research is practical, relevant, and effective enough to have a tangible impact on practice is crucial to organizing the research com-

munity for change. It was stressed that marking such early successes will help to generate additional resources and sustained support for expanded clinical effectiveness research.

Develop a Research Paradigm That Strengthens Research Capacity

The goal of clinical effectiveness research is to provide information on the effects of interventions on treatment outcomes in routine care. From hybrid studies and the mining of large databases to practices such as cluster randomization, pragmatic trials, and practice-based investigations and new study designs (e.g., equipoise stratified randomized designs and adaptive treatment studies) or posthoc data analyses (e.g., moderator analyses), clearly many paths provide answers to clinically important questions. The research paradigm needs to provide a framework that emphasizes best practices in methodologies while strengthening overall research capacity. Research methods should be defined clearly (e.g., strengths, weaknesses, appropriateness), with unmistakable expectations for conduct and reporting of results. The research community must invest more of its talent in the evaluation of methodologies and in the establishment of clear guidelines on the standards of evidence that must be met by research—whether for approval, coverage, or publication.

Greater attention to matching study design to appropriate research questions also will allow a broader use of methods and drive improvements in the approaches and data resources needed to support a new generation of research. For example, as the number of databases and clinical registries has increased, researchers have developed new means to deal with threats to validity—both external validity, as in the development of effectiveness research, and internal validity—including approaches that exploit the concepts of proxy variables using high-dimensional propensity scores and exploiting provider variation in prescribing preference using instrumental variable analysis. New study designs such as adaptive trials and genome-wide association studies are being developed to exploit diverse information sources. A framework that embraces these new tools and techniques and that focuses on understanding the best approach to answering key questions will enable the research community to not only probe questions of clinical effectiveness but also to explore opportunities to extend and improve the overall approach to research.

Likewise, a paradigm that focuses on state-of-the-art design and conduct of methods will drive needed improvements in emerging data resources. Research will continue to benefit more from having large data streams, registries, and billing databases, but only if we contend with important statistical and data aggregation issues. In particular, new methods are needed to pool data from diverse sources. Detailed documentation of sources and

quality control also will be needed to ensure data integrity and use. The structure of these data resources must be considered to minimize false discovery rates.

Supporting Innovation

Several participants stressed the importance of efforts to supply the talent, resources, and opportunities needed for innovation. Faced with the growing diversity and quantity of data available, it was noted that developing approaches to integrating data—that do not depend on tools or specific standards—would truly transform our ability to harness these data. This and other emerging technical challenges underscore the importance of generating a cadre of investigators and innovators who can take on these and other obstacles to matching the capacity for discovery with the astounding rate at which data are generated.

The research community also needs opportunities and incentives to test tools such as hybrid, preference-based, or quasi-experimental designs, statistical tools, and modeling approaches to better understand their appropriate use. Some of these new analytic tools are already adding to our knowledge base, but with sufficient innovation incentives researchers can define a new generation of studies that make even greater gains in efficiency and accuracy. To ensure that these new techniques are fully developed, tested, and appropriately adopted, funding might be redirected to accommodate greater experimentation with methodologies. Traditional approaches to research funding and policy will need to shift to support innovation.

Lifecycle Approach to Evidence Development

The efficacy assessments that lead to a product’s approval traditionally have been considered the end stage of evidence development. However, a lifecycle approach to evidence development begins with efficacy testing in the preapproval stage and continues throughout the postmarket environment. This shows the findings, often significant, that often occur when a product is given to real-world patient populations. Throughout a product’s lifecycle, new questions emerge on efficacy and effectiveness. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide information about efficacy, and hybrid approaches that combine the best attributes of RCTs with complementary methodology have been employed to develop more information on effectiveness. The recently completed National Institute of Mental Health-sponsored comparative effectiveness trials of antipsychotic medications in patients with schizophrenia (the CATIE trials), for example, blended features of efficacy studies and large, simple trials to provide extensive information. Staging or sequencing methods is an opportunity to better integrate

trials and studies for clinical effectiveness evidence development across a product’s lifecycle. Several participants raised the prospects of coverage with evidence development approaches and support of specialty society registries to support these types of postmarket evidence generation.

Infrastructure

The postmarket environment will become increasingly important in clinical research. It was suggested that realizing the potential for personalized medicine is predicated on the development of a system that will support research that is increasingly bidirectional, drawing from and contributing to clinical care. Similarly, other participants noted, in many cases sufficient evidence exists to guide practice, yet that evidence is not applied enough. Identification and exploration of evidence-based “best practices” will improve understanding of barriers to effective application of evidence. Additional knowledge also might inform the research community about the system components needed to capture information at the point of care for continuous refinement of practice guidelines and decision support tools. Drawing research closer to practice will require new approaches to practice and funding as well as to infrastructure improvement.

To turn genetic findings into knowledge that can be applied at the patient level, for example, researchers will need to use information technology to collect, catalog, organize, and analyze data on genotype, biodata, and phenotype. A long-term vision for the infrastructure required is of robust and standardized electronic health records (EHRs) deployed nationwide that are designed for research as well as of patient and provider support. A tool that captures information systematically and aggregates, normalizes, and synthesizes data in ways that enable efficient analyses is still a distant prospect. However, specialty society registries offer opportunities for immediate progress. These clinical data resources have been used to conduct postmarket studies as well as large-scale trials. Considerable progress is being made in the development of tools, strategies, and policies that will enable multiple users from different sites, perhaps even competitors, to access some of the large databases. A key improvement to these resources would be greater linkage and horizontal integration to ensure the focus is on patient care rather than on a single disease.

The need for greater linkage and greater coordination between efforts was also a strong theme in discussions of infrastructure needs. Several examples of networked resources, such as the HMO Research Network (HMORN) and the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSAs) institutions, were suggested as important infrastructures on which to build. Coordination capacity and platforms for collaboration on issues of mutual interest for collaboration also were viewed as needed infrastructure. For

example, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, payers, and manufacturers might be convened to identify priority areas for methods advancement and enhancement. Opportunities to strengthen collaborative efforts of academia, industry, and government, perhaps through public–private partnerships, were also suggested, with several panelists viewing the public sector as critical in providing an enabling platform between academics and the private sector.

There was also an emphasis on supporting and reinforcing existing and planned infrastructure to strengthen research capacity. Collaboration will be needed in efforts to aggregate data from diverse sources, construct measures consistently, and better use existing data resources. Other efforts to move to more integrated data capabilities, including the addition of clinical data to administrative databases will expand research capacity. Another key opportunity for collaboration was around coverage with evidence development. From the private-sector perspective, such efforts are complicated by the approval needed from all impacted states. Although coverage conditional on the development of needed evidence would ideally be supported by all payers, regulatory issues need to be resolved, including those related to collusion. Related areas for collaborative work included developing a common language for contracting and intellectual property issues and addressing privacy and security issues to facilitate more efficient research while protecting the patient. Although broad-scale change on these dimensions may require legislation, in the near term, collaboration between relevant parties could serve to identify and resolve the many inconsistencies and inefficiencies that now present unnecessary obstacles to important research efforts. Clarification of the interpretation of Institutional Review Boards was viewed as a particularly pressing example of an area in need of collaborative work.

Infrastructure currently in development, such as that for postmarket surveillance, was also discussed as a key opportunity. These postmarket, or Phase IV, studies are typically carried out in a fragmented fashion, with multiple organizations conducting separate investigations. If developed and supported carefully and adequately, this infrastructure will enable a more thorough approach to evidence development.

COMMON THEMES2

The presentations and discussions were rich and stimulating and elicited important insights on our evolving clinical research capacity. The following

|

BOX 7-1 Redesigning the Clinical Effectiveness Research Paradigm

|

highlights a number of common themes heard throughout the course of the workshop (Box 7-1), as well as possible multistakeholder activities for consideration by the IOM Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care and its members.

-

Address current limitations in applicability of research results. Because clinical conditions and their interventions have complex and varying circumstances, there are different implications for the evidence needed, study designs, and the ways lessons are applied: the internal and external validity challenge. In particular given our aging population, often people have multiple conditions—co-morbidities—yet study designs generally focus on people with just one condition, limiting their applicability. In addition, although our assessment of candidate interventions is primarily through pre-market studies, the opportunity for discovery extends throughout the lifecycle of an intervention—development, approval, coverage, and the full period of implementation.

-

Counter inefficiencies in timeliness, costs, and volume. Much of current clinical effectiveness research has inherent limits and inefficiencies related to time, cost, and volume. Small studies may have insufficient reliability or follow-up. Large experimental studies may be expensive and lengthy but have limited applicability to practice circumstances. Studies sponsored by product manufacturers have to overcome perceived conflicts and may not be fully used. Each incremental unit of research time and money may bring greater con-

-

fidence but also carries greater opportunity costs. There is a strong need for more systematic approaches to better defying how, when, for whom, and in what setting an intervention is best used.

-

Define a more strategic use to the clinical experimental model. Just as there are limits and challenges to observational data, there are limits to the use of experimental data. Challenges related to the scope of possible inferences, to discrepancies in the ability to detect near-term versus long-term events, to the timeliness of our insights and our ability to keep pace with changes in technology and procedures, all must be managed. Part of the strategy challenge is choosing the right tool at the right time. For the future of clinical effectiveness research, the important issues relate not to whether randomized experimental studies are better than observational studies, or vice versa, but to what’s right for the circumstances (clinical and economic) and how the capacity can be systematically improved.

-

Provide stimulus to new research designs, tools, and analytics. An exciting part of the advancement process has been the development of new tools and resources that may quicken the pace of our learning and add real value by helping to better target, tailor, and refine approaches. Use of innovative research designs, statistical techniques, probability, and other models may accelerate the timeliness and level of research insights. Some interesting approaches using modeling for virtual intervention studies may hold prospects for revolutionary change in certain clinical outcomes research.

-

Encourage innovation in clinical effectiveness research conduct. The kinds of “safe harbor” opportunities that exist in various fields for developing and testing innovative methodologies for addressing complex problems are rarely found in clinical research. Initiative is needed for the research community to challenge and assess its approaches—a sort of meta-experimental strategy—including those related to analyzing large datasets, in order to learn about the purposes best served by different approaches. Innovation is also needed to counter the inefficiencies related to the volume of studies conducted. How might existing research be more systematically summarized or different research methods be organized, phased, or coordinated to add incremental value to existing evidence?

-

Promote the notion of effectiveness research as a routine part of practice. Taking full advantage of each clinical experience is the theoretical goal of a learning healthcare system. But for the theory to move closer to the practice, tools and incentives are needed for caregiver engagement. A starting point is with the anchoring of

-

the focus of clinical effectiveness research planning and priority setting on the point of service—the patient–provider interface—as the source of attention, guidance, and involvement on the key questions to engage. The work with patient registries by many specialty groups is an indication of the promise in this respect, but additional emphasis is necessary in anticipation of the access and use of the technology that opens new possibilities.

-

Improve access and use of clinical data as a knowledge resource. With the development of bigger and more numerous clinical data sets, the potential exists for larger scale data mining for new insights on the effectiveness of interventions. Taking advantage of the prospects will require improvements in data sharing arrangements and platform compatibilities, the addressing of issues related to real and perceived barriers from interpretation of privacy and patient protection rules, enhanced access for secondary analysis to federally sponsored clinical data (e.g., Medicare part D, pharmaceutical, clinical trials), the necessary expertise, and stronger capacity to use clinical data for postmarket surveillance.

-

Foster the transformational research potential of information technology. Broad application and linkage of electronic health records holds the potential to foster movement toward real-time clinical effectiveness research that can generate vastly enhanced insights into the performance of interventions, caregivers, institutions, and systems—and how they vary by patient needs and circumstances. Capturing that potential requires working to better understand and foster the progress possible, through full application of electronic health records, developing and applying standards that facilitate interoperability, agreeing on and adhering to research data collection standards by researchers, developing new search strategies for data mining, and investing patients and caregivers as key supporters in learning.

-

Engage patients as full partners in the learning culture. With the impact of the information age growing daily, access to up-to-date information by both caregiver and patient changes the state of play in several ways. The patient sometimes has greater time and motivation to access relevant information than the caregiver, and a sharing partnership is to the advantage of both. Taking full advantage of clinical records, even with blinded information, requires a strong level of understanding and support for the work and its importance to improving the quality of health care. This support may be the most important element in the development of the learning enterprise. In addition, the more patients understand and communicate with their caregivers about the evolving nature of evidence, the less

-

disruptive will be the frequency and amplitude of public response to research results that find themselves prematurely, or without appropriate interpretative guidance, in the headlines and the short-term consciousness of Americans.

-

Build toward continuous learning in all aspects of care. This foundational principle of a learning healthcare system will depend on system and culture change in each element of the care process with the potential to promote interest, activity, and involvement in the knowledge and evidence development process, from health professions education to care delivery and payment.

ISSUES FOR POSSIBLE ROUNDTABLE FOLLOW-UP

Among the range of issues engaged in the workshop’s discussion were a number that could serve as candidates for the sort of multistakeholder consideration and engagement represented by the Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care, its members, and their colleagues.

Clinical Effectiveness Research

-

Methodologies. How do various research approaches best align to different study circumstances—e.g., nature of the condition, the type of intervention, the existing body of evidence? Should Roundtable participants develop a taxonomy to help identify the priority research advances needed to strengthen and streamline current methodologies and to consider approaches for their advancement and adoption?

-

Priorities. What are the most compelling priorities for comparative effectiveness studies, and how might providers and patients be engaged in helping to identify them and set the stage for research strategies and funding partnerships?

-

Coordination. Given the oft-stated need for stronger coordination in the identification, priority setting, design, and implementation of clinical effectiveness research, what might Roundtable members do to facilitate evolution of the capacity?

-

Clustering. The National Cancer Institute is exploring the clustering of clinical studies to make the process of study consideration and launching quicker and more efficient? Should this be explored as a model for others?

-

Registry collaboration. Since registries offer the most immediate prospects for broader “real-time” learning, can Roundtable participants work with interested organizations on periodic convening

-

of those involved in maintaining clinical registries, exploring additional opportunities for combined efforts and shared learning?

-

Phased intervention with evaluation. How can progress be accelerated in the adoption by public and private payers of approaches to allow phased implementation and reimbursement for promising interventions for which effectiveness and relative advantage has not been firmly established? What sort of neutral venue would work best for a multistakeholder effort through existing research networks (e.g., CTSAs, HMORN)?

-

Patient preferences and perspectives. What approaches might help to refine practical instruments to determine patient preferences—such as the NIH’s PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System)—and apply them as central elements of outcome measurement?

-

Public–private collaboration. What administrative vehicles might enhance opportunities for academic medicine, industry, and government to engage cooperatively in clinical effectiveness research? Would development of common contract language be helpful in facilitating public–private partnerships?

-

Clinician engagement. Should a venue be established for periodic convening of primary care and specialty physician groups to explore clinical effectiveness research priorities, progress in practice-based research, opportunities to engage in registry-related research, and improved approaches to clinical guideline development and application?

-

Academic health center engagement. With academic institutions setting the pattern for the predominant approach to clinical research, drawing prevailing patterns closer to broader practice bases will require increasing the engagement with community-based facilities and private practices for practice-based research. How might Roundtable stakeholders partner with the Association of American Medical Colleges and Association of Academic Health Centers to foster the necessary changes?

-

Incentives for practice-based research. Might an employer–payer working group from the Roundtable be useful in exploring economic incentives to accelerate progress in using clinical data for new insights by rewarding providers and related groups working to improve knowledge generation and application throughout the care process?

-

Condition-specific high-priority effectiveness research targets. Might the Roundtable develop a working group to characterize the gap between current results and what should be expected, based on current treatment knowledge, strategies for closing the

-

gap, and collaborative approaches (e.g., registries) for the following conditions:

-

-

Adult oncology

-

Orthopedic procedures

-

Management of co-occurring chronic diseases?

-

Clinical Data

-

Secondary use of clinical data. Successful use of clinical data as a reliable resource for clinical effectiveness evidence development requires the development of standards and approaches that assure the quality of the work. How might Roundtable members encourage or foster work of this sort?

-

Privacy and security. What can be done within the existing structures and institutions to clarify definitions and reduce the tendencies for unnecessarily restrictive interpretations on clinical data access, in particular related to secondary use of data?

-

Collaborative data mining. Are there ways that Roundtable member initiatives might facilitate the progress of EHR data mining networks working on strategies, statistical expertise, and training needs to improve and accelerate postmarket surveillance and clinical research?

-

Research-related EHR standards. How might EHR standard-setting groups be best engaged to ensure that standards developed are research friendly, developed with the research utility in mind, and have the flexibility to adapt as research tools expand?

-

Transparency and access. What vehicles, approaches, and stewardship structures might best improve the receptivity of the clinical data marketplace to enhanced data sharing, including making federally sponsored clinical data more widely available for secondary analysis (data from federally supported research, as well as Medicare-related data)?

Communication

-

Research results. Since part of the challenge in public misunderstanding of research results is a product of “hyping” by the research community, how might the Roundtable productively explore the options for “self-regulatory guidelines” on announcing and working with media on research results?

-

Patient involvement in the evidence process. If progress in patient outcomes depends on deeper citizen understanding and engagement as full participants in the learning healthcare system—both

-

as partners with caregivers in their own care, and as supporters of the use of protected clinical data to enhance learning—what steps can accelerate?

As interested parties consider these issues, we need to remember that the focus of the research discussed at the workshop is, ultimately, for and about the patient. The goals of the work are fundamentally oriented to bringing the right care to the right person at the right time at the right price. The fundamental questions we seek to answer for any healthcare intervention are straightforward: Can it work? Will it work—for this patient in this setting? Is it worth it? Do the benefits outweigh any harms? Do the benefits justify the costs? Do the possible changes offer important advantages over existing alternatives?

Finally, despite the custom of referring to “our healthcare system,” the research community in practice functions as a diverse set of elements that often seems to connect productively only by happenstance. Because shortfalls in coordination and communication impinge on the funding, effectiveness, and efficiency of the clinical research process—not to mention its progress as a key element of a learning healthcare system—the notion of working productively together is vital for both patients and the healthcare community. Better coordination, collaboration, public–private partnerships, and priority setting are compelling priorities, and the attention and awareness generated in the course of this meeting are important to the Roundtable’s focus on redesigning the clinical effectiveness research paradigm.