Summary

In the legislation calling for an assessment of America’s climate choices, Congress directed the National Research Council (NRC) to “investigate and study the serious and sweeping issues relating to global climate change and make recommendations regarding the steps that must be taken and what strategies must be adopted in response to global climate change.” As part of the response to this request, the America’s Climate Choices Panel on Limiting the Magnitude of Future Climate Change was charged to “describe, analyze, and assess strategies for reducing the net future human influence on climate, including both technology and policy options, focusing on actions to reduce domestic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and other human drivers of climate change, but also considering the international dimensions of climate stabilization” (see Appendix B for the full statement of task).

Our panel responded to this charge by evaluating the choices available for the United States to contribute to the global effort of limiting future climate change. More specifically, the panel focused on strategies to reduce concentrations of GHGs in the atmosphere, including strategies that are technically and economically feasible in the near term, as well as strategies that could potentially play an important role in the longer term.

Because policy that limits climate change is highly complex and involves a wide array of political and ethical considerations, scientific analysis does not always point to unequivocal answers. We offer specific recommendations in cases where research clearly shows that certain strategies and policy options are particularly effective; but in other cases, we simply discuss the range of possible choices available to decision makers. On the broadest level, we conclude that the United States needs the following:

-

Prompt and sustained strategies to reduce GHG emissions. There is a need for policy responses to promote the technological and behavioral changes necessary for making substantial near-term GHG emission reductions. There is also a need to aggressively promote research, development, and deployment of new technologies, both to enhance our chances of making the needed emissions reductions and to reduce the costs of doing so.

-

An inclusive national framework for instituting response strategies and policies. National policies for limiting climate change are implemented through the actions of private industry, governments at all levels, and millions of households

-

and individuals. The essential role of the federal government is to put in place an overarching, national policy framework designed to ensure that all of these actors are furthering the shared national goal of emissions reductions. In addition, a national policy framework that both generates and is underpinned by international cooperation is crucial if the risks of global climate change are to be substantially curtailed.

-

Adaptable means for managing policy responses. It is inevitable that policies put in place now will need to be modified in the future as new scientific information emerges, providing new insights and understanding of the climate problem. Even well-conceived policies may experience unanticipated difficulties, while others may yield unexpectedly high levels of success. Moreover, the degree, rate, and direction of technological innovation will alter the array of response options available and the costs of emissions abatement. Quickly and nimbly responding to new scientific information, the state of technology, and evidence of policy effectiveness will be essential to successfully managing climate risks over the course of decades.

While recognizing that there is ongoing debate about the goals for international efforts to limit climate change, for this analysis we have focused on a range of global atmospheric GHG concentrations between 450 and 550 parts per million (ppm) CO2-equivalent (eq), a range that has been extensively analyzed by the scientific and economic communities and is a focus of international climate policy discussions. In evaluating U.S. climate policy choices, it useful to set goals that are consistent with those in widespread international use, both for policy development and for making quantitative assessments of alternative strategies.

Global temperature and GHG concentration targets are needed to help guide long-term global action. Domestic policy, however, requires goals that are more directly linked to outcomes that can be measured and affected by domestic action. The panel thus recommends that the U.S. policy goal be stated as a quantitative limit on domestic GHG emissions over a specified time period—in other words, a GHG emissions budget.

The panel does not attempt to recommend a specific budget number, because there are many political and ethical judgments involved in determining an “appropriate” U.S. share of global emissions. As a basis for developing and assessing domestic strategies, however, the panel used recent integrated assessment modeling studies1 to suggest

|

1 |

Specifically, we drew upon the Energy Modeling Forum 22 studies (http://emf.stanford.edu/research/emf22/). See Box 2.2 for details about this study and the reasons it was deemed particularly useful for our purposes. |

that a reasonable “representative” range for a domestic emissions budget would be 170 to 200 gigatons (Gt) of CO2-eq for the period 2012 through 2050. This corresponds roughly to a reduction of emissions from 1990 levels by 80 to 50 percent, respectively. We note that this budget range is based on “global least cost” economic efficiency criteria for allocating global emissions among countries. Using other criteria, different budget numbers could be suggested. (For instance, some argue that, based on global “fairness” concerns, a more aggressive U.S. emission-reduction effort is warranted.)

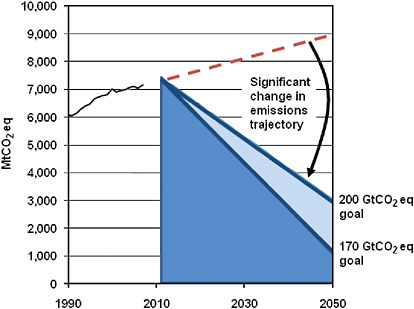

As illustrated in Figure S.1, meeting an emissions budget in the range suggested above, especially the more stringent budget of 170 Gt CO2-eq, will require a major departure from business-as-usual emission trends (in which U.S. emissions have been rising at a rate of ~1 percent per year for the past three decades). The main drivers of GHG emissions are population growth and economic activity, coupled with energy use per capita and per unit of economic output (“energy intensity”). Although the energy intensity of the U.S. economy has been improving for the past two decades, total emis-

FIGURE S.1 Illustration of the representative U.S. cumulative GHG emissions budget targets: 170 and 200 Gt CO2-eq (for Kyoto gases) (Gt, gigatons, or billion tons; Mt, megatons, or million tons). The exact value of the reference budget is uncertain, but nonetheless illustrates a clear need for a major departure from business as usual.

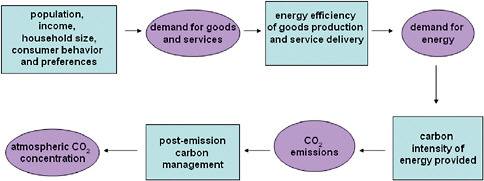

FIGURE S.2 The chain of factors that determine how much CO2 accumulates in the atmosphere. The blue boxes represent factors that can potentially be influenced to affect the outcomes in the purple circles.

sions will continue to rise without a significant change from business as usual. Our analyses thus indicate that, without prompt action, the current rate of GHG emissions from the energy sector would consume the domestic emissions budget well before 2050.2

More than 80 percent of U.S. GHG emissions are in the form of CO2 from combustion of fossil fuels. As illustrated in Figure S.2, there is a range of different opportunities to reduce emissions from the energy system, including reducing demand for goods and services requiring energy, improving the efficiency with which the energy is used to provide these goods and services, and reducing the carbon intensity of this energy supply (e.g., replacing fossil fuels with renewables or nuclear power, or employing carbon capture and storage).

To evaluate the magnitude and feasibility of needed changes in all of these areas, we examined the results of a recent NRC study, America’s Energy Future, which estimated the technical potential for aggressive near-term (i.e., for 2020 and 2035) deployment of key technologies for energy efficiency and low-carbon energy production. We compared this to estimates of the technology deployment levels that might be needed to meet the representative emissions budget. This analysis suggests that limiting domestic GHG emissions to 170 Gt CO2-eq by 2050 by relying only on these near-term opportunities may be technically possible but will be very difficult. Meeting the 200-Gt CO2-eq goal will be somewhat less difficult but also very demanding. In either case, however, falling short of the full technical potential for technology deployment is

likely, as it would require overcoming many existing barriers (e.g., social resistance and institutional and regulatory concerns).

Some important opportunities exist to control non-CO2 GHGs (such as methane, nitrous oxide, and the long-lived fluorinated gases) and to enhance biological uptake of CO2 through afforestation and tillage change on suitable lands. These opportunities are worth pursuing, especially as a near-term strategy, but they are not large enough to make up the needed emissions reductions if the United States falls short in reducing CO2 emissions from energy sources.

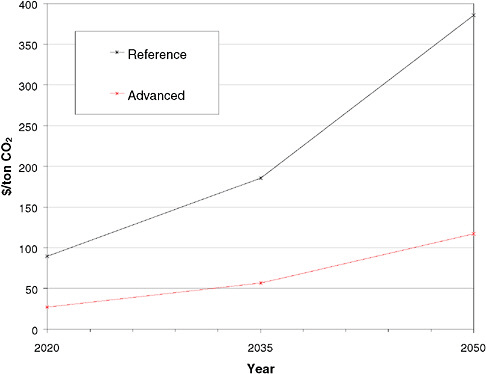

Acting to reduce GHG emissions in any of these areas will entail costs as well as benefits, but it is difficult to estimate overall economic impacts over time frames spanning decades. While different model projections suggest a range of possible impacts, all recent studies indicate that gross domestic product (GDP) continues to increase substantially over time. Studies also clearly indicate that the ultimate cost of GHG emission reduction efforts depends upon successful technology innovation (Figure S.3).

We thus conclude that there is an urgent need for U.S. action to reduce GHG emissions. In response to this need for action, we recommend the following core strategies to U.S. policy makers:

-

Adopt a mechanism for setting an economy-wide carbon-pricing system.

-

Complement the carbon price with a portfolio of policies to

-

realize the practical potential for near-term emissions reductions through energy efficiency and low-emission energy sources in the electric and transportation sectors;

-

establish the technical and economic feasibility of carbon capture and storage and new-generation nuclear technologies; and

-

accelerate the retirement, retrofitting, or replacement of GHG emission-intensive infrastructure.

-

-

Create new technology choices by investing heavily in research and crafting policies to stimulate innovation.

-

Consider potential equity implications when designing and implementing climate change limiting policies, with special attention to disadvantaged populations.

-

Establish the United States as a leader to stimulate other countries to adopt GHG reduction targets.

-

Enable flexibility and experimentation with policies to reduce GHG emissions at regional, state, and local levels.

-

Design policies that balance durability and consistency with flexibility and capacity for modification as we learn from experience.

FIGURE S.3 A model projection of the future price of CO2 emissions under two scenarios: a “reference” case that assumes continuation of historical rates of technological improvements and an “advanced” case with more rapid technological change. The absolute costs are highly uncertain, but studies clearly indicate that costs are reduced dramatically when advanced technologies are available. SOURCE: Adapted from Kyle et al. (2009).

These recommendations are each discussed in greater detail below.

Adopt a mechanism for setting an economy-wide carbon pricing system (see Chapter 4).

A carbon pricing strategy is a critical foundation of the policy portfolio for limiting future climate change. It creates incentives for cost-effective reduction of GHGs and provides the basis for innovation and a sustainable market for renewable resources. An economy-wide carbon-pricing policy would provide the most cost-effective reduc-

tion opportunities, would lower the likelihood of significant emissions leakage,3 and could be designed with a capacity to adapt in response to new knowledge.

Incentives for emissions reduction can be generated either by a taxation system or a cap-and-trade system. Taxation sets prices on emissions and lets quantities of emissions vary; cap-and-trade systems set quantity limits on emissions and let prices vary. There are also options for hybrid approaches that integrate elements of both taxation and cap-and-trade systems.

Any such systems face common design challenges. On the question of how to allocate the financial burden, research strongly suggests that economic efficiency is best served by avoiding free allowances (in cap-and-trade) or tax exemptions. On the question of how to use the revenues created by tax receipts or allowance sales, revenue recycling could play a number of important roles—for instance, by supporting complementary efforts such as research and development (R&D) and energy efficiency programs, by funding domestic or international climate change adaptation efforts, or by reducing the financial burden of a carbon-pricing system on low-income groups.

In concept, both tax and cap-and-trade mechanisms offer unique advantages and could provide effective incentives for emission reductions. In the United States and other countries, however, cap-and-trade has received the greatest attention, and we see no strong reason to argue that this approach should be abandoned in favor of a taxation system. In addition, the cap-and-trade system has features that are particularly compatible with other of our recommendations. For instance, it is easily compatible with the concept of an emissions budget and more transparent with regard to monitoring progress toward budget goals. It is also likely to be more durable over time, since those receiving emissions allowances have a valued asset that they will likely seek to retain.

High-quality domestic and international GHG offsets can play a useful role in lowering the overall costs of achieving a specific emissions reduction, both by expanding the scope of a pricing program to include uncovered emission sources and by offering a financing mechanism for emissions reduction in developing countries (although only for cases where adequate certification, monitoring, and verification are possible, including a demonstration that the reductions are real and additional). Note, however, that using international offsets as a way to meet the domestic GHG emissions budget could ultimately create a more onerous emissions-reduction burden for the countries

selling the offsets; absent some form of compensation to ease this burden, seller countries may resist the use of offsets that are counted against their own emission budget.

Complement the carbon-pricing system with policies to help realize the practical potential of near-term technologies; to accelerate the retrofit, replacement, or retirement of emission-intensive infrastructure; and to create new technology choices (see Chapters 3, 4, and 5).

Pricing GHGs is a crucial but insufficient component of the effort to limit future climate change. Because many market barriers exist and a national carbon pricing system will take time to develop and mature, a strategic, cost-effective portfolio of complementary policies is necessary to encourage early actions that increase the likelihood of meeting the 2050 emissions budget. This policy portfolio should have three major objectives, listed below.

1.

Realize the practical potential for near-term emission reductions.

End-use energy demand and the technologies used for electricity generation and transportation drive the majority of U.S. CO2 emissions. Key near-term opportunities for emission reductions in these areas include the following:

-

Increase energy efficiency. Enhancing efficiency in the production and use of electricity and fuels offers some of the largest near-term opportunities for GHG reductions. These opportunities can be realized at a relatively low marginal cost, thus leading to an overall lowering of the cost of meeting the 2050 emissions budget. Furthermore, achieving greater energy efficiency in the near term can help defer new power plant construction while low-GHG technologies are being developed.

-

Increase the use of low-GHG-emitting electricity generation options, including the following:

-

Accelerate the use of renewable energy sources. Renewable energy sources offer both near-term opportunities for GHG emissions reduction and potential long-term opportunities to meet global energy demand. Some renewable technologies are at and others are approaching economic parity with conventional power sources (even without a carbon-pricing system in place), but continued policy impetus is needed to encourage their development and adoption. This includes, for instance, advancing the development of needed transmission infrastructure, offering long-term stability in financial incentives, and encouraging the mobilization of private capital support for research, development, and deployment.

-

-

-

Address and resolve key barriers to the full-scale testing and commercial-scale demonstration of new-generation nuclear power. Improvements in nuclear technology are commercially available, but power plants using this technology have not yet been built in the United States. Although such plants have a large potential to reduce GHG emissions, the risks of nuclear power such as waste disposal and security and proliferation issues remain significant concerns and must be successfully resolved.

-

Develop and demonstrate power plants equipped with carbon capture and storage technology. Carbon capture and storage4 could be a critically important option for our future energy system. It needs to be commercially demonstrated in a variety of full-scale power plant applications to better understand the costs involved and the technological, social, and regulatory barriers that may arise and require resolution.

-

-

Advance low-GHG-emitting transportation options. Near-term opportunities exist to reduce GHGs from the transportation sector through increasing vehicle efficiency, supporting shifts to energy-efficient modes of passenger and freight transport, and advancing low-GHG fuels (such as cellulosic ethanol).

2.

Accelerate the retirement, retrofitting, or replacement of emissions-intensive infrastructure.

Transitioning to a low-carbon energy system requires clear and credible policies that enable not only the deployment of new technologies but also the retrofitting, retiring, or replacement of existing emissions-intensive infrastructure. However, the turnover of the existing capital stock of the energy system may be very slow. Without immediate action to encourage retirements, retrofitting, or replacement, the existing emissions-intensive capital stock will rapidly consume the U.S. emissions budget.

3.

Create new technology choices.

The United States currently has a wide range of policies available to facilitate technological innovation, but many of these policies need to be strengthened, and in some cases additional measures enacted, to accelerate the needed technology advances. The magnitude of U.S. government spending for (nondefense) energy-related R&D has declined substantially since its peak nearly three decades ago. The United States also

lags behind many other leading industrialized countries in the rate of government spending for energy-related R&D as a share of national GDP. While recommendations for desired levels and priorities for federal energy R&D spending are outside the scope of this study, we do find that the level and stability of current spending do not appear to be consistent with the magnitude of R&D resources needed to address the challenges of limiting climate change. In the private sector as well, compared to other U.S. industries, the U.S. energy sector spends very little on R&D relative to income or sales profits.

Research is a necessary first step in developing many new technologies, but bringing innovations to market requires more than basic research. Policies are also needed to establish and expand markets for low-GHG technologies, to more rapidly bring new technologies to commercial scale (especially support for large-scale demonstrations), to foster workforce development and training, and more generally to improve our understanding of how social and behavioral dynamics interact with technology and how technological changes interact with the broader societal goals of sustainable development.

Consider potential equity implications when designing and implementing policies to limit climate change, with special attention to disadvantaged populations (see Chapter 6).

Low-income groups consume less energy per capita and therefore contribute less to energy-related GHG emissions. Yet, low-income and some disadvantaged minority groups are likely to suffer disproportionately from adverse impacts of climate change and may also be adversely affected by policies to limit climate change. For instance, energy-related goods make up a larger share of expenditures in poor households, so raising the price of energy for consumers may impose the greatest burden on these households. Likewise, limited discretionary income may preclude these households from participating in many energy-efficiency incentives. Because these impacts are likely but not well understood, it will be important to monitor the impacts of climate change limiting policies on poor or disadvantaged communities and to adapt policies in response to unforeseen adverse impacts. Some key strategies to consider include the following:

-

structuring policies to offset adverse impacts to low-income and other disadvantaged households (for instance, structuring carbon pricing policies to provide relief from higher energy prices to low-income households);

-

designing incentive-based climate change limiting policies to be accessible to poor households (such as graduated subsidies for home heating or insulation improvements);

-

ensuring that efforts to reduce energy consumption in the transport sector avoid disadvantaging those with already limited mobility; and

-

actively and consistently engaging representatives of poor and minority communities in policy planning efforts.

Major changes to our nation’s energy system will inevitably result in shifting employment opportunities, with job gains in some sectors and regions but losses in others (i.e., energy-intensive industries and regions most dependent on fossil fuel production). Policy makers could help smooth this transition for the populations that are most vulnerable to job losses through additional, targeted support for educational, training, and retraining programs.

Establish the United States as a leader to stimulate other countries to adopt GHG emissions reduction targets (see Chapter 7).

Even substantial U.S. emissions reductions will not, by themselves, substantially alter the rate of climate change. Although the United States is responsible for the largest share of historic contributions to global GHG concentrations, all major emitters must ultimately reduce emissions substantially. However, the indirect effects of U.S. action or inaction are likely to be very large. That is, what this nation does about its own GHG emissions will have a major impact on how other countries respond to the climate change challenge, and without domestic climate change limiting policies that are credible to the rest of the world, no U.S. strategy to achieve global cooperation is likely to succeed. Continuing efforts to inform the U.S. public of the dangers of climate change and to devise cost-effective response options will therefore be essential for global cooperation as well as for effective, sustained national action.

The U.S. international climate change strategy will need to operate at multiple levels. Continuing attempts to negotiate a comprehensive climate agreement under the United Nations Climate Change Convention are essential to establish good faith and to maximize the legitimacy of policy. At the same time, intensive negotiations must continue with the European Union, Japan, and other Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (i.e., high-income) countries and with low- and middle-income countries that are major emitters of, or sinks for, GHGs (especially China, India, Brazil, and countries of the former Soviet Union). These multiple tracks need to be pursued in ways that reinforce rather than undermine one another. It may be worth-while to negotiate sectoral as well as country-wide agreements, and GHGs other than CO2 should be subjects for international consideration. In such negotiations, the United States should press for institutional arrangements that provide credible assessment and verification of national policies around the world and that help the low- and middle-income countries attain their broader goals of sustainable development.

Competition among countries to take the lead in advancing green technology will play an important role in stimulating emissions-reduction efforts, but strong cooperative efforts will be needed as well. Sustaining large, direct governmental financial transfers to low-income countries may pose substantial challenges of political feasibility; however, large financial transfers via the private sector could be facilitated via a carbon pricing system that allows purchases of allowances or offsets. There is a clear need for support of innovative scientific and technical efforts to help low- and middle-income countries limit their emissions. To provide leadership in these efforts, the United States needs to develop and share technologies that not only reduce GHG emissions but also help advance economic development and reduce local environmental stresses.

Enable flexibility and experimentation with emissions-reduction policies at regional, state, and local levels (see Chapter 7).

State and local action on climate change has already been significant and wide-ranging. For instance, states are operating cap-and-trade programs, imposing performance standards on utilities and auto manufacturers, running renewable portfolio standard programs, and supporting and mandating energy efficiency. Cities across the United States are developing and implementing climate change action plans. Many federal policies to limit climate change will need ongoing cooperation of states and localities in order to be successfully implemented—including, for example, energy-efficiency programs, which are run by localities or state-level programs, and energy-efficiency building standards, which are sometimes enacted statewide and implemented by local authorities. Moreover, states have regulatory capacity (for example, in regulating energy supply and implementing building standards) that may be needed for implementing new federal initiatives.

Subnational programs will thus need to continue playing a major role in meeting U.S. climate change goals. In addition, since climate change limiting policies will continue to evolve, policy experimentation at subnational levels will provide useful experience for national policy makers to draw upon. On the other hand, subnational regulation can pose costs, such as the fact that businesses operating in multiple jurisdictions may face multiple state regulatory programs and therefore increased compliance burdens. Overlap with state cap-and-trade programs can make a federal program less effective by limiting the freedom of the market to distribute reductions efficiently. These costs, however, may be worth the benefits gained from state and local regulatory innovation; regardless, they illustrate the trade-offs Congress will have to consider when deciding whether to preempt state action.

Thus, a balance must be struck to preserve the strengths and dynamism of state and

local actions, while tough choices are made about the extent to which national policies should prevail. In some instances, it may be appropriate to limit state and local authority and instead mandate compliance with minimum national standards. But Congress could promote regulatory flexibility and innovation across jurisdictional boundaries when this is consistent with effective and efficient national policy. To this end, we suggest that Congress avoid punishing or disadvantaging states (or entities within the states) that have taken early action to limit GHG emissions, avoid preempting state and local authority to regulate GHG emissions more stringently than federal law without a strong policy justification, and ensure that subnational jurisdictions have sufficient resources to implement and enforce programs mandated by Congress.

Design policies that balance durability and consistency with flexibility and capacity for modification as we learn from experience (see Chapter 8).

The strategies and policies outlined above are complex efforts with extensive implications for other domestic issues and for international relations. It is therefore crucial that policies be properly implemented and enforced and be designed in ways that are durable and resistant to distortion or undercutting by subsequent pressures. At the same time, policies must be sufficiently flexible to allow for modification as we gain experience and understanding (as discussed earlier in this Summary). Transparent, predictable mechanisms for policy evolution will be needed.

There are inherent tensions between these goals of durability and adaptability, and it will be an ongoing challenge to find a balance between them. Informing such efforts requires processes for ensuring that policy makers regularly receive timely information about scientific, economic, technological, and other relevant developments. One possible mechanism for this process is a periodic (e.g., biennial) collection and analysis of key information related to our nation’s climate change response efforts. This effort could take the form of a “Climate Report of the President” that would provide a focal point for analysis, discussion, and public attention and, ideally, would include requirements for responsible implementing agencies to act upon pertinent new information gained through this reporting mechanism.