CHAPTER SEVEN

Multilevel Response Strategies

The primary focus of this report is on national-scale strategies for limiting the magnitude of future climate change. Successfully addressing climate change in the long run, however, requires encouraging simultaneous actions at many scales and capitalizing on the unique benefits to be found at each different scale of action (as discussed by Sovacool and Brown [2009] and Ostrom [2010]). National policy goals will be implemented through the actions of the private sector, state and local governments, and individuals and households. Federal policy needs to provide a framework within which all of these actors can work effectively toward a shared national goal. Similarly, national policy provides a crucial foundation for the role that the United States needs to play internationally in the global effort to limit climate change. This chapter first discusses how U.S. domestic policies can foster strong emissions-reduction efforts by other countries. It then considers how to devise a division of responsibility between federal and state authorities that will promote experimentation within a consistent national policy framework.

INTERNATIONAL STRATEGIES

As discussed in Chapter 2, controlling U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will not by itself have a decisive impact on global atmospheric GHG concentrations. However, what the United States does about its own GHG emissions is likely to have a major impact on how other countries respond to climate change. Many countries around the world are already taking strong steps toward lowering their GHG emissions. Lack of action by the United States, however, can serve as an excuse for inaction by others; conversely, if the United States acts vigorously, more countries are likely to follow. U.S. action on climate change, therefore, is as important (if not more important) in regard to its impacts on other countries’ behavior as its impact on actual U.S. emissions.

Because climate change is a global issue, many aspects of U.S. climate policy have international implications. Chapter 4 discussed the role of international offsets in domestic climate change policy and how a domestic cap-and-trade system could be linked to international climate agreements. Chapter 6 discussed the ancillary benefits for international relations of effective climate change response measures. This section focuses on strategies for engaging effective international participation in efforts to limit the magnitude of climate change. We discuss U.S. policies in relation to interna-

tional incentives and the institutions needed to achieve climate change objectives. We then consider specific U.S. policies that could be directed toward low- and middle-income countries where emissions are rising most rapidly, and we illustrate the strategic and contingent nature of the policy problem with three scenarios for future action among these countries. Finally, we examine the roles of both competition and cooperation in encouraging international action to limit climate change.

U.S. Policies and International Incentives

The outcome of efforts to limit climate change will depend on other countries’ decisions, but the United States has considerable ability to affect other countries’ behavior. As a result, the situation involves strategic interaction; that is, nations’ policies and ability to cooperate with one another depend not only on their own preferences and resources, but on leaders’ beliefs about others’ preferences, resources, and strategies (Schelling, 1960; Waltz, 1979). For the United States to engage with other countries most effectively, it needs a strategy for crafting policies that affect the incentives faced by other governments.

The incentive problem is profoundly affected by the fact that climate change policy relates to a common pool resource (or “global commons”): a resource that it is difficult or impossible to exclude others from enjoying but that is degraded by use. In this case, the desired global commons is an atmosphere with a lower concentration of GHGs than would otherwise be the case. Common pool resources are not self-managing; promoting sustained cooperation requires formal institutions involving rules and social norms (Ostrom, 1990).

International institutions (such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [UNFCCC] and the Kyoto Protocol) provide principles, rules, and practices around which expectations converge. When credible, they affect beliefs about others’ behavior, provide focal points for action, and therefore can affect incentives and outcomes even without having coercive power over states. They can facilitate cooperation by reducing the costs of making and enforcing agreements, providing information, enhancing the credibility of statements by governments and other actors, and providing for the delegation of authority (Hawkins et al., 2006; Ikenberry, 2000; Keohane, 1984). Since these institutions rarely have coercive power, however, they depend on favorable configurations of state preferences and are subject to change when prevailing preferences change.1

|

1 |

Empirical support for the essential role of international institutions in global environmental policy is provided by data from the International Energy Agency (IEA) Database Project (http://iea.uoregon.edu/): |

Within international institutions, strategies of reciprocity (making benefits conditional on contributions to the common good) are often the most effective way to generate cooperation, as is generally the case in the international trade system (Barton et al., 2007). It is conceivable that trade-related reciprocity could be employed to provide incentives for other countries to pursue effective climate-change policies. Over-reliance on such a strategy, however, could lead to acrimony and open opportunities for self-interested protectionism by import-competing firms and labor in wealthy countries. Other strategies must be employed to provide incentives for action.

Among these other key strategies for international engagement, it remains crucial to continue to push for strong domestic GHG reduction policies. Without clear, transparent U.S. leadership on this issue, any attempts at fostering greater international engagement are likely to be unsuccessful. A sustainable U.S. domestic strategy must be based on broad public consensus about the importance of limiting climate change, and on policies crafted to meet the interests of key stakeholders in both the public and private sectors. In general, “environmental regulations work most effectively when systems of regulation confer tangible benefits upon the regulated” (Oye and Maxwell, 1995).

The Role of Multilateral Institutions

Climate change policy faces an institutional dilemma. High-income countries have the capacity to take strong action to reduce GHG emissions, and they have growing incentives to do so as understanding of the potential damages from climate change grows. But such efforts will be insufficient to limit the extent of global climate change without effective action by the low- and middle-income countries with rapidly growing emissions—countries that numerically dominate multilateral institutions including the United Nations (UN) and the UNFCCC.

The largest of these countries, such as China, India, and Brazil, likewise have incentives to act, as they are major contributors to the problem and may be highly vulnerable to climate change impacts. But having secured exemptions from obligations in the Kyoto Protocol, they are now disinclined to sacrifice those bargaining advantages. The smaller low- and middle-income countries, meanwhile, lack incentives to act vigorously, since climate change is a common-pool resource issue, subject to dilemmas of collective action (that is, small contributors to a common-pool resource problem are strongly tempted to free-ride on the efforts of others).

Low- and middle-income countries find some protection in the procedures of majority-run international organizations in which they are numerically preponderant. In contrast, in bilateral negotiations with the United States and other high-income countries, or with international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, low- and middle- income countries (except for China and India) are at a profound disadvantage. The implication of this for international engagement is that the formal UN-centered process cannot be abandoned, as this would alienate scores of countries and give strong rhetorical ammunition to voices opposing any action by low- and middle-income countries. Yet, in a huge unwieldy international negotiation with many diverse interests, deadlock can set in. For instance, a decade of active negotiation was required for the Law of the Sea Treaty, an issue that was neither as complex nor as important for economic growth as is climate change. Roughly 20 countries are responsible for 75 percent of global emissions (WRI, 2010). The institutional dilemma of climate change policy is how to combine continued adherence to a UN-centered framework with assurance that agreements among the major emitters are not prevented or undermined by countries whose emissions are small.

The need for global governance institutions is indicated by the fact that governments repeatedly resort to them. But sovereignty and conflicting state interests ensure that most such institutions will lack simple coherent structures. Many international institutions and networks have some bearing on climate change, but none are comprehensive or authoritative. The complex range of existing global governance institutions reflects the large variety of interests, bureaucratic organizations, and capacities in and among states. This is an inherent characteristic of world politics, not a problem to be solved. Different problems generate different solutions, and different solutions generate different governance arrangements. Since a single, comprehensive, binding global climate change agreement is unlikely, a multiplicity of mechanisms, linked but not characterized by a single coherent architecture, should be expected to persist. This might include, for example, sectoral-based agreements, discussed in Box 7.1.

Even when agreements are reached, however, they will not be implemented automatically. Commitments by governments at international meetings may or may not lead to real action, since such commitments are made in the context of a political process that is often decoupled from implementation. Likewise, even elaborate plans made at the international level do not necessarily mean very much in terms of practical implementation, and they are often vague on metrics for assessment. In general, plans are a lot easier to produce than to implement, as experience with the Kyoto Protocol shows.

In the context of international negotiations, credibility is at a premium. The history of relationships between high- and low-income countries is replete with unfulfilled

|

BOX 7.1 Sectoral Agreements As discussed in Chapter 4, in the absence of a comprehensive global climate agreement, measures to limit GHG emissions imposed only in high-income economies raise the prospect that a GHG-emitting industry could simply relocate to an emerging-economy country. As a consequence, the international competitiveness of industry in high-income countries could be damaged, and the emissions leakage involved in shifting the location of emissions would reduce the ultimate effectiveness of the policy (see Chapter 4 for further discussion of emissions leakage). Anticipation of such effects would generate political opposition to effective regulation in the high-income countries. One way to respond to such concerns is to establish global agreements governing relatively well-defined industrial sectors, such as steel and aluminum production, auto manufacturing, and air transport. Such agreements could involve all countries, particularly emerging economies, and would therefore help address issues of competitiveness and leakage. Unlike a comprehensive carbon-pricing system, however, a complex of sectoral agreements would not equalize the marginal costs of emissions control within a jurisdiction. Sectoral agreements should therefore be seen as a potentially useful interim supplementary practice to limit emissions, rather than as a viable long-term substitute for agreements based on economy-wide caps. Nevertheless, as long as a deep comprehensive agreement involving all countries remains unattainable, sectoral agreements could play a useful role in limiting emissions. The opportunities and challenges of expanding such efforts into more widespread mandatory agreements have been explored in a number of recent analyses (Pew Center, 2007; WBCSD, 2009; WRI, 2007; IEA series at http://www.iea.org/subjectqueries/sectoralapproaches.asp [accessed September 17, 2010]). |

promises. Independent assessment is essential for credibility. As emphasized in ACC: Informing an Effective Response to Climate Change (NRC, 2010b), such assessment requires valid standardized methodologies for GHG emissions reporting and verification. Measurement and verification at the international level are particularly difficult due to the absence of institutions with legal powers to inspect sites and sovereignty concerns that limit expansion of such powers. Agreement on valid verification methodologies does not necessarily ensure compliance, if states selling emissions allowances have incentives to cheat on the rules. Since centralized enforcement is difficult or impossible in world politics, constructing a system of buyer liability—modeled on bond markets in which securities of varying quality sell at varying prices—could generate decentralized monitoring and market-generated incentives for compliance (Keohane and Raustiala, 2009). The essential point is that, because enforcement of any

international agreement is not likely to be centralized, states must have incentives to implement their own commitments.

Varying perspectives and institutional fragmentation suggest that reaching a meaningful comprehensive agreement on climate change is likely to be a long-term process. Binding global GHG emissions limits cannot be imposed by high-income countries. In the near term, some combination of incomplete international agreements and more specific limited-membership or bilateral agreements is likely. The United States should therefore seek to use the UN process to generate multilateral agreements insofar as feasible but, failing effective global action, should rely also on agreements among major emitters and bilateral accords. In some cases, two countries, or a small set of countries, may have common interests and expertise not shared by others; for example, China and the United States both have interests in developing carbon capture and storage technology. In other cases, if a small group of states forms a “club” that generates benefits exclusive to members, as the European Union has, other states may develop interest in joining rather than holding out for a more favorable deal (Downs et al., 2000).

The United States is already a party to numerous bilateral and multilateral arrangements focused on limiting climate change, including, for instance, the Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate, the Asia-Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate, the G-8 + 5 Climate Change Dialogue, the Methane to Markets Partnership, the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership, the U.S.–China Partnership on Climate Change, the U.S.–India Nuclear Partnership, and many other activities focused on advancing specific low-carbon energy technologies (e.g., CCS, hydrogen, Gen IV Nuclear, fusion energy). The panel supports continued U.S. involvement and leadership in such efforts, in conjunction with attempts to negotiate appropriate global agreements under the UN.

As discussed in Chapter 3, there is also strong motivation for forging an international agreement to control hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), greenhouse gases which are the main class of chlorofluorocarbon replacement compounds. Controlling HFCs through the Montreal Protocol may be the best strategy, because the expertise and support structures already existing within that framework could easily be adopted for the applications in which HFCs are used. This also makes sense because HFCs (except by-product HFC-23) are ozone-depleting substance substitutes and, thus, logically fall under the Montreal Protocol’s mandate.

In the long run, reaching a meaningful, binding global accord for addressing climate change will depend both on U.S. actions at home and on effective U.S. diplomacy that takes account of the perspectives of other countries. Imagination and resolve will be

required, both to identify effective incentives for widespread participation and to ensure rigorous assessment and enforcement of national commitments. All are requisite elements of a credible global solution.

Distinctive Perspectives of Low- and Middle-Income Countries

As discussed earlier, a significant fraction of the emissions reductions required to stabilize global atmospheric GHG concentrations must take place in low- and middle-income countries whose emissions are rapidly increasing. U.S. policy makers will need to understand the positions of leaders and publics in these countries. Some key points to consider include the following:

-

Low- and middle-income countries are focused on the need for economic growth, and governments currently in power are unlikely to survive if they fail to produce acceptable rates of growth for their own economies. Hence, these governments have strong incentives not to accept any measures—such as emissions taxes or binding caps on emissions—that could significantly reduce their rates of economic growth. For them to agree to binding targets there would have to be “substantial evidence both that low-carbon growth is feasible and that there will be substantial external technological and financial assistance along the way” (Stern, 2009).

-

Low- and middle-income countries often have low and uneven administrative capacity, which makes it difficult to implement complex policies. For a detailed discussion of this issue as applied to India, for example, see Rai and Victor (2009).

-

Low- and middle-income countries, by definition, have large numbers of people living below the poverty line (as defined by the World Bank), and their GHG emissions per capita are much lower than that of high-income countries. Historically (between 1850 and 2000), the high-income countries emitted more than three times as much CO2 (from fossil fuels and cement) than the low- and middle-income countries. Equity considerations thus underlie the common demand that high-income countries take the first serious measures to deal with climate change, and that low- and middle-income countries receive compensation in return for their own actions.

-

The leaders and publics in some low- and middle-income countries are profoundly suspicious of the motivations and actions of the high-income countries, and they are worried that the burdens of adjusting to climate change will be imposed on them, as reflected in financial and trade policies.

-

As discussed in Chapter 6, certain actions that would be beneficial from a climate standpoint—such as limiting black carbon emissions from domestic stoves and diesel engines—would also create substantial health benefits for the countries concerned. Low- and middle-income countries have self-interest incentives to reduce these pollutants.

-

Most low- and middle-income countries want to avoid being considered outliers in world politics by failing to join open international institutions. The concept of “common but differentiated responsibilities” embodied in the Kyoto Protocol grew from this interest in belonging to legitimate international institutions but not having to accept onerous obligations. It is likely that most low- and middle-income countries will seek to keep this concept as the defining principle of a global climate strategy.

-

From the perspective of the low- and middle-income countries, the United States and other high-income countries will be credible in their demands for action only if they take effective action to limit their own GHG emissions, and if they use international institutions for addressing the problem rather than relying solely on bilateral negotiations or ad hoc groupings.

The different experiences and perspectives between low- and middle-income countries and most high-income countries mean that irreconcilable frameworks for analysis and rhetoric persist. For example, framing climate change as a global commons problem conflicts with framing it in terms of equity. Future-oriented problem-solving perspectives conflict with orientations that seek compensation for past injustices.

Although it is important to appreciate the distinctive common perspectives that exist among low- and middle-income countries, one should not lose sight of the substantial economic, political, and institutional differences among these countries. Some are democracies; some are not. Some have substantial administrative competence to regulate GHGs; others have difficulty implementing any complex regulations. Hence, specific U.S. policies directed toward low- and middle-income countries will have to be carefully differentiated.

The Montreal Protocol and its successor agreements for addressing the problem of stratospheric ozone depletion illustrate that strategies can sometimes be found to overcome the types of problems discussed above; for instance, by setting delayed deadlines for developing countries and establishing a multilateral fund to help them make the transition (Parson, 2003). Yet the cost and complexity of climate change are much greater than for ozone depletion, and forging global cooperation on climate change is a far more difficult problem than the one faced by drafters of the Montreal Protocol.

Contingent Strategies: Three Scenarios

Effective action is always contingent on political realities, and U.S. international strategy must therefore be adaptable to different political configurations evolving over time. The negotiating situation on climate change, as on other international issues, is a “two-level game” (Putnam, 1988): strategies in domestic politics and international politics interact in both directions and must be coordinated. Note, for instance, the useful example provided by Great Britain, which has unconditionally promised a certain level of domestic effort on climate change but also promised further efforts that are conditional on greater action by others (Committee on Climate Change, 2008).

Because it is not possible to predict future developments in global politics, it is instructive to consider a variety of scenarios of the positions that may be taken by key players in a global climate agreement and to evaluate what each scenario might mean for U.S. response strategy. Three scenarios, presented below, all assume willingness by high-income countries to enact vigorous policies to limit the magnitude of climate change, because nothing of consequence can be achieved internationally unless this condition is met. Hence, there is no “business-as-usual” scenario.

Scenario 1:

Independent but Coordinated Action

Under the first scenario, all major governments would commit independently to action on climate change, which they would self-finance. Under these conditions, the major task would be coordination: reaching agreement in a situation in which all states had fundamentally compatible interests (Martin, 1992). The issue of carbon pricing could be dealt with through a harmonized set of taxes or (more likely in view of contemporary policies in the European Union and the United States) through either a global cap-and-trade program (Frankel, 2009) or linked national cap-and-trade programs (Jaffe and Stavins, 2009). Large-scale financial transfers would not be required, but joint technology development and transfers would be needed (Newell, 2009). Implementation would be chiefly a national problem, because all countries would be committed to effective action. There would probably need to be an international institution to assess and monitor implementation, providing reassurance to everyone that the burdens were actually being shared. Trade competitiveness issues would not be salient because all countries would undertake comparable obligations.

One could argue that independent action would be beneficial for low- and middle-income countries. For instance, it is noted in Chapter 6 that measures to limit climate change can have substantial agricultural and health co-benefits for these countries.

This scenario, however, seems unlikely to be politically realistic within the next few decades. It would require costly efforts by low- and middle-income countries that many are disinclined even to consider, and such efforts would have to be undertaken by governments that are short of material and administrative resources. In the long run, however, if low- and middle-income countries eventually become more prosperous, independent action could become more realistic.

Scenario 2:

A Global Regime with Financial Transfers

To reach a serious international agreement under the UNFCCC, with meaningful action by low- and middle-income countries, some financial transfers from richer to poorer countries seem essential. Indeed, contemporary proposals from some developing countries demand that burdens of funding climate change response (both limiting and adaptation) must be undertaken almost exclusively by high-income countries. There is little evidence, however, to suggest that publics and legislatures in high-income countries are willing to directly provide resources at levels that have been demanded, which could involve hundreds of billions of dollars of financial transfers annually. Such demands contrast sharply with the politics of climate change legislation in the U.S. Congress, which has focused on compensating domestic firms and individual voters and on appealing to an interest in long-term national energy security and job growth. It seems particularly unlikely that the United States would send very large financial resources to China without compensation of some kind, given the fact that China is a major holder of U.S. government securities and a principal economic rival.

Financial transfers could take place in a cap-and-trade regime involving offsets, or in which the caps applied to low- and middle-income countries are arranged to provide substantial headroom (or “hot air”). International offsets could thereby play a positive role by encouraging other countries to adopt sectoral or economy-wide caps in order to have access to the U.S. market. Under these circumstances, the high-income countries would benefit by having to undertake less domestic effort to reach a particular target, and low- and middle-income countries would benefit financially. (Note that the potential pitfalls of international offsets are discussed in earlier chapters.)

Any major financial transfers to low- and middle-income countries would surely have to be tied to technology transfer and other specific measures that help assure the public that their funding is actually contributing to genuine, additional emissions reductions. Whether this international regime involved some sort of new global institution or was built upon established organizations such as the World Bank, the institu-

tional demands would be substantial. Creating a system that could generate effective incentives for compliance and continued commitment would require considerable institutional ingenuity (Kingsbury et al., 2009).

Scenario 3:

A Partial Regime Without Financial Transfers

In a third scenario, the high-income countries would go ahead with vigorous programs to limit emissions but would refuse to make large international financial transfers; low- and middle-income countries would refuse to take vigorous action that they would have to finance themselves. This sort of global regime would be very unsatisfactory in terms of emissions limitation worldwide, and it would raise serious issues of competitiveness insofar as producers in low-income countries were exempted from the costs of emissions control measures. (Similar issues would arise in scenario 2 as a result of financial transfers that relieved producers in low-income countries of the full costs of emissions reductions.) Issues of emissions leakage would be particularly serious.

In this scenario, it would be important to identify “win-win” technological advances (for example, improved agricultural methods that reduce emissions without sacrificing yields, or efficient, low-emissions coal-fired power plants) that help low- and middle-income countries to reduce emissions through measures that promote their economic development. In the absence of financial transfers, creative technological solutions and institutions to facilitate technology transfer would be especially important.

Of great value in this regard are international cooperative efforts such as the International Partnership for Energy Efficiency Cooperation (which helps governments identify and implement policies and programs for promoting energy efficiency) and international cooperative research and development (R&D) activities, such as those listed earlier in this section. A few studies have explored optimal policy strategies for fostering this type of international cooperation (e.g., Golombek and Hoel, 2009; Qiu and Tao, 1998).

Competition and Climate Change

Although explicit cooperation is one way to induce effective action, competition can also generate measures to help limit the magnitude of climate change. Governments are increasingly coming to understand the opportunities for economic growth that can result from playing a leadership role in the transition to a new “green” industrial era. Private-sector and government actions can change rapidly when climate change

response is seen as essential for economic competitiveness. China, for example, is actively seeking to maintain growth, create jobs, and increase the competitiveness of its industries by becoming a leader in technologies to conserve energy and reduce GHG emissions. Japan and many EU countries have aggressively moved in this direction as well. Active U.S. engagement in this “race to the top” will both enhance our own future economic growth and motivate other countries to continue moving ahead.

Border Tax Adjustments (BTAs) provide one strategy for inducing more action by reluctant countries and for strengthening the position of negotiators for countries with large potential markets. On the other hand, BTAs are potentially dangerous because (if applied unilaterally) they would be subject to interest-group pressures. And if such measures become protectionist, other countries could retaliate, damaging the international trading system.

A joint report from the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP and WTO, 2009) suggests that such border adjustments could be legal under WTO rules if two conditions are met: (1) there is a close connection between the means employed and a climate change policy that is either necessary for the protection of human, plant, or animal life or health or relating to the preservation of exhaustible natural resources; and (2) the measure is applied in nondiscriminatory ways that do not serve as “a disguised restriction on international trade.” A WTO Appellate Body also insisted that administrative due process be respected: Countries that are the target of environmentally related trade measures must be consulted. Measures to address climate change would meet the first criterion and, if properly applied, could meet the second as well.

The implication is that BTAs could be a valuable part of a climate change policy portfolio, but only if they are firmly established within the WTO-centered international trade regime. Establishing nondiscriminatory BTAs could help to reassure domestic producers about competitiveness, prevent emissions leakage, and at the same time encourage more vigorous action by other countries. They could strengthen the positions of negotiators for countries seeking to take global leadership on climate change. But these policies must conform to WTO law, both substantively and in terms of due process.

As a general strategy then, the United States should strive to promote cooperative measures to limit the magnitude of climate change but should also be alert to ways in which competition can sometimes foster desirable results. A judicious combination of cooperation and competition can generate strong incentives for effective action.

KEY CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Even substantial U.S. emissions reductions will not, by themselves, substantially alter the rate of climate change. Although the United States is responsible for the largest share of historic contributions to global GHG concentrations, all major emitters will need to ultimately reduce emissions substantially. However, the indirect effects of U.S. action or inaction are likely to be very large. That is, what this nation does about its own GHG emissions will have a major impact on how other countries respond to the climate change challenge; without domestic climate change limiting policies that are credible to the rest of the world, no U.S. strategy to achieve global cooperation is likely to succeed. Continuing efforts to inform the U.S. public of the dangers of climate change and to devise cost-effective response options will therefore be essential for both global cooperation and effective national action.

The U.S. climate change strategy will need to be multidimensional, operating at multiple levels. Continuing attempts to negotiate a comprehensive climate agreement under the UN Climate Change Convention are essential to establish good faith and to maximize the legitimacy of policy. At the same time, intensive negotiations must continue with the European Union, Japan, and other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, and with low- and middle-income countries that are major emitters of, or sinks for, GHGs (especially China, India, Brazil, and the former Soviet Union countries). These multiple tracks need to be pursued in ways that reinforce rather than undermine one another. It may be worthwhile to negotiate sectoral agreements as well, and GHGs other than CO2 should be subjects for international consideration. In such negotiations, the United States should press for institutional arrangements that provide credible assessment and verification of national policies around the world, and that help low- and middle- income countries attain their broader goals of sustainable development.

Competition among countries to take the lead in low-GHG technology industries will play an important role in stimulating emissions-reduction efforts, but strong cooperative efforts will be needed as well. Sustaining large direct government-to-government financial transfers to low-income countries may pose substantial challenges of political feasibility, but large financial transfers via the private sector could be facilitated via a carbon pricing system that allows international purchases of allowances or offsets. There is a clear need for innovative, cooperative scientific and technological efforts to help low- and middle-income countries limit their emissions. To provide leadership in these efforts, the United States needs to develop and share technologies that not only reduce GHG emissions but also help advance economic development and reduce local environmental stresses.

BALANCING FEDERAL WITH STATE AND LOCAL ACTION

Congress faces complex questions about how to harness the current interest and efforts of state and local authorities while striking an appropriate balance between national policy and state/local regulatory autonomy. This section analyzes how to approach these issues and provides key examples of policy areas that are likely to raise significant questions about overlaps between federal and state policies.

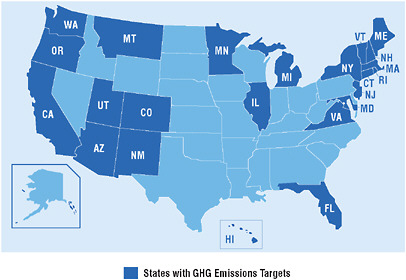

Many states and localities have enacted far-reaching climate policies over the past several years. Researchers estimate that over 50 percent of Americans live in a jurisdiction that has enacted a GHG emissions cap (Lutsey and Sperling, 2008). Figure 7.1 shows the states that have adopted emissions caps and targets, many of which are more aggressive than those being proposed in recent national legislation (i.e., H.R. 2454). In addition, 29 states that contain more than half of the U.S. population have enacted renewable portfolio standards (http://www.pewclimate.org/). Fifteen states, representing 30 percent of the country, have indicated their intent to follow California GHG emissions standards for automobiles.2 The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is already up and running among many northeastern states. California has adopted an ambitious plan to implement its economy-wide emissions cap, passed legislation requiring its localities to incorporate GHG emissions targets into land-use planning, and prohibited importation into the state of electricity that is more GHG-intensive than efficient natural gas facilities. Several states have adopted performance emissions standards for large GHG emitters.

The scope and magnitude of these state programs is potentially enormous, although significant questions remain about whether many of the state programs are more aspirational than real. Nevertheless, if states with emissions caps are successful in achieving their most ambitious targets (and assuming no emissions leakage), the cumulative emissions reductions would approach the 2020 national emissions-reduction targets proposed in H.R. 2454.

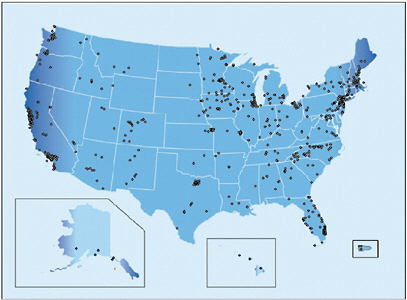

Significant growth has also occurred in the scope of climate change response actions occurring at the local/urban level. More than 1,000 mayors have joined the U.S. Conference of Mayor’s Climate Protection Agreement, vowing to reduce GHG emissions in their cities below 1990 levels (Figure 7.2). We cannot assess the progress these cities are making in meeting their proposed goals, but there is clearly a great interest and capacity for municipal-scale action to influence many activities and planning deci-

FIGURE 7.1 States that have adopted emissions caps and targets. SOURCE: Pew Center for Global Climate Change.

FIGURE 7.2 Cities participating in the U.S. Mayor’s Climate Protection Agreement (http://www.usmayors.org/climateprotection/ClimateChange.asp, accessed September 17, 2010).

sions that affect GHG emissions (e.g., land-use and zoning decisions, infrastructure investment, municipal service delivery, and management of schools, recreation areas, municipal buildings, etc.).

The role of states and localities will also be very important in the implementation and enforcement of many national policies. In most states, for example, cities and counties are responsible for enacting and enforcing building standards. If Congress chooses to enact national building standards, it will still need to rely on localities to ensure that the standards are actually implemented and enforced. If Congress mandates performance standards for certain GHG sources (such as new coal-fired power plants), state-level environmental agencies will be responsible for issuing permits consistent with those standards. Most energy-efficiency building programs are administered at the state and local levels, so if Congress funds large energy-efficiency programs, it will need to rely on subnational jurisdictions to implement those programs.

Encouraging regulatory flexibility across jurisdictional boundaries increases our nation’s opportunities to gain valuable experience from state-level experimentation. A key way to ensure this flexibility is for Congress to avoid preempting state and local authority to regulate GHG emissions more stringently than federal law unless there is a strong policy justification for doing so. As a general rule of thumb, we suggest that state action should be preempted only if it is likely to shift significant externalities onto out-of-state residents and consumers—for instance, through leakage of emissions outside the state’s borders. Another preemption consideration is the potential burden multiple state and local standards can place on business interests that operate in multiple states with overlapping and/or inconsistent regulations.

Rather than using its preemptive powers to limit state and local regulatory policy, Congress could require states and localities to regulate through the establishment of minimum national standards in areas such as renewable portfolio standards and building standards. This is a commonplace approach in many federal environmental statutes, including the Clean Air Act (CAA) and the Clean Water Act. Minimum national standards may be particularly appropriate for policies traditionally within the purview of states and localities that promise large, cost-effective emissions reductions—such as building efficiency standards.

In considering the appropriate roles that states and localities should play in climate policy, it is also important to consider the way in which various judicial doctrines can preempt state and local action, even where Congress has not passed legislation expressly intended to preempt. When adopting GHG emissions-reduction policies, Congress should make it clear when it intends states and localities to retain independent regulatory authority. Finally, unless there is strong reason, states that have taken early

action to reduce GHG emissions should not be penalized by the adoption of federal climate policy.

Below are some examples of policy areas that are likely to raise significant questions about overlapping federal and state policy.

Example: Cap and Trade

Chapter 4 contains a detailed discussion of the policy design challenges associated with a cap-and-trade system. In that discussion, it is noted that one major regional cap-and-trade program (RGGI) is already up and running; other areas of the country are cooperating to possibly establish additional programs (e.g., the Western Climate Initiative). These programs vary in their coverage, with RGGI limited to CO2 emissions from the power sector, while the Western Climate Initiative has at least initially recommended multisector coverage. Two important questions about the relationship between state and regional programs and federal law arise if the federal government adopts a cap-and-trade program.

First is the question of preemption. State cap-and-trade programs may cover more sources or impose a tighter cap than a comparable federal program. If federal legislation contains provisions that significantly undermine its effectiveness (e.g., overly generous safety valves or borrowing provisions), then a more stringent state program could compensate through additional emissions reductions within the state. With a federal cap in place, however, more stringent state caps may not actually produce any net decrease in U.S. emissions. Rather, this may simply help the rest of the country meet the federal cap more easily, because fewer reductions will be required outside of those states with stringent caps. Thus, state cap-and-trade programs may simply redistribute the allocation of emissions reductions and limit the freedom of a carbon market to distribute reductions efficiently (McGuinness and Ellerman, 2008).

Congress could allow states to effectively lower the federal emissions cap by permitting them to influence the overall number of allowances in the market. For example, a state with a cap-and-trade program could be allowed to prohibit its sources from selling unused allowances on the open market. Similarly, a state could auction allowances and then use revenue from the auction to purchase and retire federal allowances.

If state cap-and-trade programs are not preempted (i.e., are allowed to continue), and in-state sources are restricted more stringently than out-of-state sources, this may increase the overall costs of emissions reductions within the state. And if fewer sources are subject to a cap-and-trade program, this may increase volatility in the market for

allowances (McGuinness and Ellerman, 2008). It may also increase compliance costs for companies that operate nationwide, if they are required to meet multiple state program requirements. Conversely, if state or regional cap-and-trade programs are preempted, states may have difficulty meeting their own stated emissions targets (if they are more stringent than the targets proposed in recent federal legislation).

Another incentive for states to enact cap-and-trade programs more stringent than a federal program is to maintain funding streams for supporting state-level programs, for instance, related to energy efficiency, renewable energy, and R&D. By shifting costs onto in-state sources, more stringent state programs can lower allowance prices for the rest of the country, conceivably making adoption of a national cap-and-trade program more politically feasible.

Whether Congress should preempt state cap-and-trade programs is, therefore, a matter of debate. On the one hand, there is good reason for Congress to avoid preempting if states with more stringent policies will themselves incur the costs of those policies rather than exporting them. On the other hand, a principal objective of a cap-and-trade scheme is to allow market forces to encourage the cheapest emissions reductions. If state programs coexist with a federal program, they risk making emissions reductions more expensive and increasing compliance costs for companies operating in multiple states.

An additional consideration is how to avoid punishing states that have taken early action to reduce GHG emissions. If a federal program preempts state or regional cap-and-trade programs already in existence and does not provide credit for state program allowances, the value of those allowances will decline to zero (a decline that could occur as soon as federal legislation passes but well before the federal program takes effect). Emissions sources with banked allowances would begin to use those allowances, driving allowance prices down. To avoid this scenario, Congress could either permit state allowances to be transferred into the federal program, and reduce the number of federal allowances by an equal amount, or it could permit state allowances in addition to the federal allowances that are allocated. The latter will, however, expand the federal cap by the total amount of the state allowances, which could compromise efforts to reach national emissions-reduction goals (McGuinness and Ellerman, 2008).

Another significant issue arises for states operating under the RGGI program. Several RGGI states auction off their allowances and use the revenues for energy efficiency and renewable resource promotion. If RGGI is preempted and no accommodation is made for the revenue loss, these programs will suffer a serious setback. Congress may thus wish to ensure that the revenues from RGGI energy efficiency and renewable resource programs are replaced by federal revenue.

Example: Clean Air Act and Preemption

The U.S. Supreme Court, in Massachusetts v. EPA, made clear that GHG emissions are “pollutants” under the Clean Air Act and that the EPA must determine whether these pollutants endanger public health and welfare. The EPA has now made such a determination (in its so-called endangerment finding). If Congress adopts GHG emissions legislation, it must clarify the extent to which the CAA will continue to cover the regulation of GHG emissions. Even if Congress amends the CAA to remove GHG emissions regulation from the statute, open questions related to the states remain.

First, for instance, is the question of whether California’s special authority to regulate mobile source emissions under the CAA should continue to cover GHG emissions. For 40 years, the state has played a pioneering role in mobile source regulation, including adopting the GHG emissions standards that form the basis of the Obama Administration’s establishment of a national Corporate Average Fuel Economy standard. The history of the exercise of California’s authority has generally followed a consistent pattern: California first adopts mobile source standards that are more stringent than federal standards, and then, if the standards are successful, the federal government follows suit. Researchers have concluded that this pattern has significant national benefits. California can engage in regulatory experimentation; other states can follow California’s lead but are not required to do so. Frequently, the California experience has demonstrated that more stringent regulations can accomplish significant pollution reductions at much lower cost than the auto industry predicted. For instance, the current “Tier II” federal auto standards are a direct result of California’s experience in adopting stringent fleet standards at far lower cost than initially predicted (Carlson, 2008), resulting in impressive pollution reductions (e.g., NOX emissions have dropped more than 99 percent below 1970 levels).

The special status granted to California also has the benefit that it limits the number of regulatory standards manufacturers must meet to two, as opposed to the potential for 50 separate state standards, thus balancing the benefits of regulatory experimentation with the advantages of a uniform regulatory standard. For all these reasons, it seems justified to argue that, as long as California’s special regulatory authority does not interfere with advancing federal efforts, it should be allowed to continue. For instance, California’s authority to enact more stringent GHG emissions standards after 2016 (when the newly announced national standards are in full effect) should be made clear in any national climate change legislation.

Second is the question of whether states should be allowed to adopt performance standards for stationary sources of GHG emissions. Currently California, Montana,

Oregon, and Washington have standards that in various forms essentially prohibit the construction and/or purchase of electricity generated from coal absent some form of sequestration. (Similar standards established in Massachusetts and New Hampshire were superseded by RGGI.) The CAA makes clear that, in regulating pollutants from stationary sources, states have the authority to exceed federal standards. So if the CAA is amended to limit the regulation of GHG emissions, Congress should be clear about whether states will retain independent authority to regulate.

A few reasons have been proposed for why states should be allowed to impose their own stationary source standards. First, states regulating in excess of federal standards would likely shift abatement costs from out of state to in-state sources In other words, the regulating state will bear the costs of its regulatory decision (McGuinness and Ellerman, 2008). Second, performance standards can have technology-forcing effects, as occurred with California’s mobile source standards for conventional pollutants. Although performance standards may reduce economic efficiency (by forcing GHG reductions in particular places rather than allowing market forces to determine the cheapest reductions), this is offset by the innovations that can result from regulatory experimentation and flexibility.

The strategy of not preempting state programs has precedents. In enacting the national cap-and-trade program for SO2 emissions, Congress did not preempt more stringent state regulation; to this day, several states continue to regulate SO2 emissions more stringently than federal standards. Similarly, when the Bush Administration adopted a cap-and-trade program for mercury (known as the Clean Air Mercury Rule, subsequently struck down by a federal appellate court), states retained the authority to regulate mercury more stringently than federal law; again, several did so.

Example: Building Standards

Building standards have traditionally remained within the purview of local governments and states. Adoption of new and more stringent standards (such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) has been uneven across jurisdictions. Given the substantial benefits of energy efficiency savings, Congress may wish to engage in “floor preemption,” in which states are required to adopt minimum energy-efficiency standards for buildings but are also allowed to exceed those minimums. This is a commonplace approach in federal environmental statutes, including the CAA and the Clean Water Act.

If Congress does enact minimal national building codes, however, it should ensure that states and/or localities responsible for implementing standards have sufficient

resources and personnel to rigorously enforce standards. These resources could potentially be funded by allowance revenue (if allowances are auctioned). Absent effective enforcement, national building standards could be significantly undermined just as recent evidence has suggested uneven-to-nonexistent enforcement by some states under the Clean Water Act. Enforcement issues are addressed in more detail in Chapter 8.

KEY CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Given the important role that state and local actions are currently playing in U.S. efforts to reduce GHG emissions, the many ways in which states and localities will be needed for implementing new federal initiatives, and the value of learning from policy experimentation at subnational levels, Congress should carefully balance federal and state/local authority and promote regulatory flexibility across jurisdictional boundaries, with consideration of factors such as the following:

-

The need to avoid preempting state/local authority to regulate GHG emissions more stringently than federal law (“ceiling preemption”) without a strong policy justification;

-

The need for any new GHG emissions-reduction policies to clearly indicate whether a state retains regulatory authority (given various judicial doctrines that can preempt state and local action even without express preemption language from Congress);

-

The need to ensure that states and localities have sufficient resources to implement and enforce any significant new regulatory burdens placed on them by Congress (e.g., national building standards); and

-

The importance of not penalizing or disadvantaging states (or entities within the states) that have taken early action to reduce GHG emissions.