5

THE CURRENT RESPONSE

This chapter briefly describes many of the programs that were in place prior to Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) or that have been developed specifically in response to the many challenges being faced by those returning from OEF and OIF and their families. While previous chapters and Appendix B allude to the many problems related to access to care, this chapter simply catalogues the available programs without any attempt to evaluate them. The chapter is divided into two main sections. The first section provides a structural overview of the Department of Defense (DOD) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health-care and benefits systems. The second section describes a sample of the federal programs and services that are available to meet the readjustment needs of returning OEF and OIF service members, veterans, and their families. The chapter does not present a comprehensive inventory of all available federal programs, nor does it present the numerous state and local programs that have been developed to meet the needs of these populations. Additionally, the committee did not explore services provided by private institutions, nor did it explore the feasibility of public-private partnerships. Those issues might be examined in the committee’s phase 2 report.

OVERVIEW OF FEDERAL BENEFITS AVAILABLE TO SERVICE MEMBERS, VETERANS, AND THEIR FAMILIES

US troops are entitled to various benefits, such as health care, disability benefits, employment assistance, and education. This section describes the systems that are in place in DOD and VA to provide those benefits.

The Department of Defense

Most DOD programs designed to meet the needs of returning OEF and OIF military personnel are overseen by the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness (USD(P&R)). That office is responsible for ensuring the readiness of the total force, including oversight of health affairs, training, morale, welfare, and quality-of-life matters for the active-duty, reserve, and National Guard components and their dependents. Four USD(P&R) offices are responsible for those programs: the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs (ASDHA), the Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Military

Community and Family Policy, the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs, and the Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Military Personnel Policy.

Health Care

The ASDHA oversees the Military Health System (MHS), which encompasses the coordinated efforts of the medical departments of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, Coast Guard, and Joint Chiefs of Staff; the Combatant Command surgeons; and private-sector health-care providers, hospitals, and pharmacies (DOD Directive 5136.01, June 4, 2008). The primary goal of the MHS is to provide emergency and long-term casualty care and to maintain the health readiness of military personnel by promoting physical and mental fitness and healthy behaviors. In addition, the MHS ensures the delivery of health care to all DOD service members, retirees, and their families. To support all those activities, the MHS devotes substantial resources to education of its medical personnel and to research and development to advance military medicine (DOD, 2009; Task Force on the Future of Military Health Care, 2007).

The MHS provides direct care to most active-duty service members through military treatment facilities (MTFs) and clinics. The direct care is supplemented by care purchased from the civilian sector. Retirees and dependent family members (see Box 5.1) of active-duty service members are also eligible to receive care at an MTF on a space-available basis; priority is given to those enrolled in TRICARE Prime.1 Worldwide, the MHS direct-care infrastructure includes 59 military hospitals, 413 medical clinics, and 413 dental clinics (TMA, 2009b), and employs over 44,000 civilians and 89,000 military personnel (Jansen, 2009). Responsibility for delivering health care to garrisoned and deployed troops remains with the health departments of the individual services—Army, Navy,2 and Air Force—which also retain considerable autonomy in the management of their own facilities and personnel. Of some 9.3 million eligible beneficiaries, by 2010, 43% will be active-duty personnel and their dependents, and 57% will be retirees and their dependents (Jansen, 2009). In 2007, 41% of all DOD eligible beneficiaries used direct care, 19% used care purchased through the TRICARE provider network, 25% used Medicare providers, and 14% used other civilian provider networks or VA services. Active-duty personnel and their dependents relied more heavily on direct care and purchased care; 58% used direct care, 32% used purchased care, and 9% used other civilian care (Andrews et al., 2008).

DOD health benefits are delivered through the TRICARE program, which is available to active-duty and reserve-component members, military retirees, and their dependent family members under one of several plans. To enroll in any TRICARE plan, service members, their families, and retirees must first establish eligibility through the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS). Active-duty and retired service members, including National Guard and reserve members activated for at least 30 days, are automatically registered in DEERS, but individual service members are responsible for registering their family members, updating their status, and ensuring that their information is current and correct (TMA, 2009c). Active-duty service members, including members of the reserve components activated for at least 30 days, are required to enroll in TRICARE Prime. Eligible service members may also enroll their dependent family members in TRICARE Prime, but dependents may choose to pay extra to enroll in TRICARE Extra, a preferred provider option–like benefit, or seek coverage through a

civilian health-insurance provider. Members of the selected reserve3 components who are not activated may choose to enroll themselves or their families in TRICARE Reserve Select, a premium-based option (Andrews et al., 2008).

Service members leaving the military and their dependents are usually eligible for transitional TRICARE coverage. Active-duty members leaving the military under other than adverse conditions and their dependent family members can receive 18 months of coverage through the Continued Health Care Benefit Program (CHCBP). Children and spouses who were enrolled in TRICARE and lose eligibility can receive CHCBP coverage for up to 36 months. Deactivated National Guard and reserve members who were called to active duty for at least 30 days and separating active-duty members who do not qualify for the CHCBP are usually eligible to receive health-care coverage for 180 days through the Transitional Assistance Management Program (TMA, 2009d).

|

BOX 5.1 Family in the Military Context Multiple definitions of family operate in the Department of Defense (DOD), each tied to specific regulatory requirements. The most common definition defines eligibility for military identification cards, which are necessary for access to health care, military exchanges, and a variety of supportive services for families. Military identification cards are currently issued to spouses and unmarried children of service members, with exceptions and additional categories defined by children’s ages, student status, or special needs and by whether the marriage ends in divorce or in death of the service member while on active duty. Spouses and unmarried children of reserve-component members are covered while the service member is on active duty for more than 30 consecutive days (TMA, 2006). Stepchildren may or may not qualify for military identification cards, depending on such factors as age, student status, and the circumstances of the biologic parents. Other military programs have adopted more inclusive definitions of family. For example, the Yellow Ribbon Reintegration program permits participation by service members’ spouses, children, parents, grandparents, siblings, and significant others (USD(P&R), 2008). In light of the fact that only about half of military members are married, new rules recently issued for the Family and Medical Leave Act expand previous definitions of family caregivers to include adult children’s parents and other kin (US Department of Labor, 2009a). In practice, some family members do not receive supportive services even when policy permits it. For example, the DOD Task Force on Mental Health (2007) recognized that military family members have difficulty in obtaining treatment for some psychologic health problems because of gaps in provider networks. In addition, families that do not conform to military definitions may have difficulty in obtaining needed services. For example, grandparents who move to military installations to care for children during parents’ deployment may have difficulty in obtaining access to military services, and this can be especially challenging in overseas locations. |

The MHS must meet statutory access standards for its TRICARE beneficiaries. The wait time for an appointment must be less than 4 weeks for a well-patient visit or a specialty-care referral, less than 1 week for a routine visit, and less than 24 hours for an urgent-care visit.4 The MHS tracks access to care metrics for all its beneficiaries and releases monthly reports.5 In addition to frequent periodic performance reports, TRICARE presents annual reports to Congress, in which TRICARE beneficiary access is compared with civilian benchmarks. In general, TRICARE beneficiaries report lower satisfaction with their health care than their civilian counterparts (60.0% versus 72.6% in FY 2008, when respondents were defined as satisfied if they rated their health care at 8 or higher on a 10-point scale) (TMA, 2009a); and active-duty service members and their families report lower satisfaction with their ability to obtain care than their retired counterparts (64% versus 72% reporting that obtaining care is “not a problem”) (Task Force on the Future of Military Health Care, 2007; TMA, 2009a).

Disability-Benefits Process

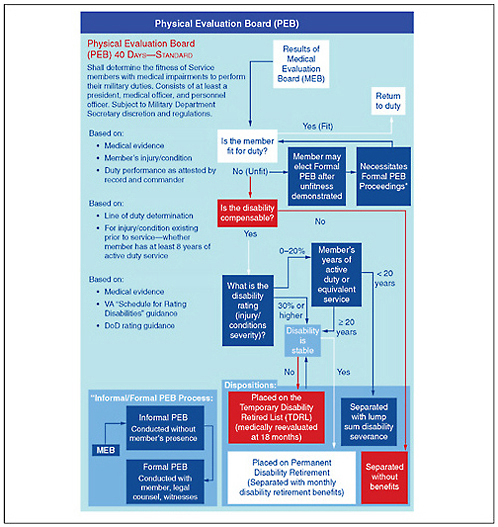

Disability benefits are provided if an injured service member qualifies. If it can be reasonably determined that a service member is not fit to resume normal duty, the service member is referred to the Medical Evaluation Board (MEB) (Task Force on Returning Global War on Terror Heroes, 2007). The MEB, composed of one or more medical officers, decides, on the basis of medical evidence and DOD guidance and regulations, whether the member meets the standards for being retained on active duty. Decisions by the MEB take a standard 30 days. If it decides that the member does not meet retention standards, he or she is referred to the Physical Evaluation Board (PEB), which includes at least one medical officer and one personnel officer. Within 40 days, the PEB decides whether the member is fit for duty, should be placed on temporary disability retired status, or should be separated with or without benefits (Figure 5.1). Military personnel who are discharged without benefits from DOD may still apply for disability benefits through VA (as discussed later in this chapter).

Health-Information System

The success of any health-care system rests not only on its physical infrastructure and care providers but on how it collects, maintains, transfers, and processes health information, especially patient records. Because of the diverse and often adverse environments in which the MHS is responsible for providing care, DOD faces many challenges in tracking and maintaining health records for all its personnel.

|

4 |

CFR §199.17(p)(5)(ii). |

|

5 |

Available on the TRICARE Operations Center Web site, http://mytoc.tma.osd.mil/AccessToCare/TOC/ATC.htm (accessed January 15, 2010). |

FIGURE 5.1 Physical Evaluation Board process.

SOURCE: Reproduced from VA Task Force on Returning Global War on Terror Heroes (2007).

DOD’s heterogeneous mixture of medical records and health-information databases presents a structural challenge in implementing an effective health-information system. Historically, each MTF has maintained its own individual health database; in addition, information on ancillary services—including pharmaceutical, laboratory, and radiology—is usually entered into a system separate from inpatient documentation, so two separate databases must be merged to create a unified patient medical record (Fravell, 2007). Further complicating the system is the difficulty inherent in transferring medical records from combat zones to

stateside providers. The telecommunication infrastructure in combat zones may be insufficient to support a Web-based electronic medical record in those areas, and this requires transfer of records, some of which might be on paper, from database to database. The more often records must be transferred, merged, and reformatted, the greater the risk that patient health information will be lost or not transferred in a timely manner (Fravell, 2007).

In addition to those structural challenges, DOD must ensure compliance with record-keeping requirements. Before the current conflicts began, the FY 1998 National Defense Authorization Act already required that DOD establish a medical tracking system for all service members who were deployed overseas, including predeployment and postdeployment medical examinations. The law also stipulated that records of the medical examinations be stored in a centralized location, and it called for DOD to put in place a quality-assurance program to ensure compliance. Although DOD is required by statute to collect health information through predeployment and postdeployment assessments, it lacks sufficient oversight to ensure full compliance with the requirement. For example, in 2007 the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that “DOD is not well-positioned to determine or assure Congress that active and reserve component service members are medically and mentally fit to deploy and to determine their medical and mental condition upon return” (GAO, 2007a). Compliance with requirements to complete predeployment and postdeployment health assessment is a particular issue in the National Guard and reserve components, which typically do not maintain a cohesive unit structure on return from deployment (GAO, 2007b).

The lack of unified electronic medical records in DOD has impeded record-sharing with VA. Because of incompatibility between the DOD and VA systems, when service members separate from the military and enter VA, their DOD health records do not transfer to VA providers. Several groups have recommended that DOD and VA develop a system that allows for medical record-sharing (GAO, 2008a; Office of the Surgeon Multinational Force–Iraq and Office of the Surgeon General United States Army Medical Command, 2008; Task Force on Returning Global War on Terror Heroes, 2007), and efforts to develop cooperative information-sharing and interoperability of medical records between DOD and VA have been going on for over a decade (GAO, 2008a). GAO finds that coordination between VA and DOD to provide medical information6 in real time is still lacking (GAO, 2008a,b). Although the departments have mounted initiatives to improve coordination (for example, the Bidirectional Health Information Exchange), a true system-wide electronic exchange of patient records remains elusive. DOD and VA are working to create a joint virtual lifetime electronic record that will track administrative and medical information for every service member for life, beginning on the day that the member enters military service (White House Office of the Press Secretary, 2009); it is unclear how long it will take to realize this goal.

The Department of Veterans Affairs

VA is composed of three main branches: the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), and the National Cemetery Administration. As a single entity, VA has the goal of providing health-care services, disability compensation, pensions, education assistance, home-loan assistance, life insurance, vocational rehabilitation and training,

and burial benefits to veterans and their families (VA, 2009g). As of 2008, VA employed a total of 288,658 to serve the 23.8 million veterans in the United States; Vietnam veterans made up the largest fraction: 33%, or 7.9 million veterans (VA, 2009d). Of the 23.8 million, 2.1 million (7.5%) were women. The total number of dependents, including children and spouses of living and deceased veterans, was 37 million.

Health Care

VHA is the largest component of VA and provides medical and rehabilitation services to veterans; it employed about 96,000 health-care professionals in FY 2008. It also provides medical training to medical students, residents, fellows, and other health-care providers. In FY 2009, Congress appropriated $44.5 billion to VHA for health care and research; this was 45% of VA’s total obligations of $98.7 billion. According to data from FY 2008, there were 7.84 million VHA enrollees—about 30% of the veteran population (IOM, 2009; VA, 2009d). As of March 2008, over 868,000 OEF and OIF service members (including National Guard and reserves) had left active duty and became eligible for VA services (GAO, 2008c). From October 2001 to January 2009, 425,538 (49%) OEF and OIF veterans enrolled in the VA system (63% from the Army, 13% Marine Corps, 12% Air Force, and 12% Navy). Of those veterans, 53% were in the active component, and 47% were in the reserve component. About 48% of the veterans are single, 45% married, 5% divorced, and 2% widowed (data provided by VA on request by the committee, September 2009).

Eligibility and Enrollment

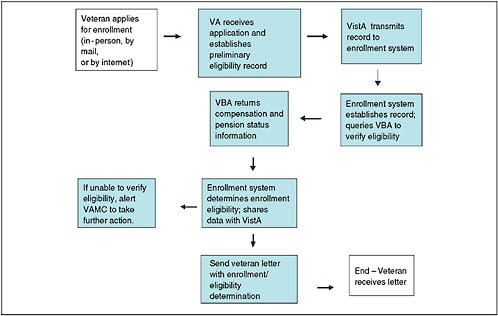

Before January 2008, combat veterans were typically eligible for benefits and health care for only 2 years after discharge. However, with the enactment of the National Defense Authorization Act (PL 110-181), veterans who served in a combat theater (including National Guard and reserves) after November 11, 1998, and were discharged or released for reasons other than dishonorable on or after January 28, 2003, now have 5 years from their date of discharge to enroll in and obtain health-care coverage from VA. That includes all OEF and OIF veterans. Determination of enrollment eligibility is made through an eight-step process (Figure 5.2), which begins when the veteran7 completes and submits the Application for Health Benefits (VA Form 10-10EZ). In 7–10 days, a decision letter is sent to the veteran stating his or her enrollment eligibility (Task Force on Returning Global War on Terror Heroes, 2007). Effective January 28, 2003, OEF and OIF veterans who enroll within the first 5 years after separating from the military are eligible for enhanced enrollment placement into priority group 6 (see Chapter 2, Table 2.5) for 5 years after discharge. Injuries or conditions related to combat service are treated by the VA health-care system free of charge.

FIGURE 5.2 VA health-care enrollment process.

NOTE: VistA = Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture8; VAMC = VA medical center.

SOURCE: VA Task Force on Returning Global War on Terror Heroes (2007).

After the designated 5 years, enrolled veterans are placed in the appropriate priority group (see Table 2.6) on the basis of income and disability; placement determines the extent of coverage and copayment amounts. Each year, VA determines whether appropriations are adequate to cover all priority groups; if not, those in the lowest groups may lose coverage (Panangala, 2007; VA, 2008a).

On July 1, 2009, the VA Health Resource Center began an outreach campaign to increase awareness of VA eligibility, enrollment procedures, and benefits for recently discharged OEF and OIF veterans and their families (VA, 2009h).

In general, VHA does not provide health-care services or coverage to spouses or dependents of veterans (IOM, 2009; VA, 2009d). However, in accordance with the Veterans’ Mental Health and Other Care Improvements Act of 2008 (S. 2162, 110th Congress), if VA services, such as marriage and family counseling or mental health care, are necessary for the proper treatment of a veteran, various family members will have access. Previously, family

members were allowed to take part in such services if they were initiated during a veteran’s hospitalization and continued only if necessary for hospital discharge.

VA may provide health-care benefits to spouses and children of veterans in a few select circumstances through the Civilian Health and Medical Program, in which VA shares the costs of medically or psychologically necessary health-care services with eligible beneficiaries. To use that program, one cannot be eligible for TRICARE and must meet the following criteria: be a spouse or child of a veteran who is rated permanently or entirely disabled because of a service-connected injury or be a surviving spouse or child of a veteran who died from a VA-rated service-connected disability or in the line of duty (most are eligible for and use TRICARE in the latter circumstance) (VA, 2009i).

Veterans Integrated Service Networks

Health care is delivered through the 23 geographically divided veterans integrated service networks (VISNs), which manage 153 VA medical centers (VAMCs), 765 community-based outpatient clinics, and 230 vet centers (see Table 5.1) (VA, 2009d). The various components provide a wide spectrum of medical services, including inpatient and outpatient care, rehabilitation and mental health care, complex specialty care, and pharmaceutical benefits and distribution. They are each managed by a VISN director who reports to the deputy under secretary for health for operations and management (IOM, 2009). Veterans who qualify (see Table 2.5) can get care on a fee-for-service basis.

TABLE 5.1 Veterans Integrated Service Networks and Numbers of Facilitiesa

|

VISN |

Hospitals and Medical Centers |

Community-Based Outpatient Clinics |

Other Outpatient Clinics |

Vet Centers |

Other Facilitiesb |

|

VISN 1: New England |

11 |

18 |

0 |

21 |

0 |

|

VISN 2: Upstate New York |

6 |

29 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

|

VISN 3: New Jersey, New York |

8 |

28 |

0 |

12 |

1 |

|

VISN 4: Stars and Stripes |

12 |

47 |

0 |

13 |

0 |

|

VISN 5: VA Capitol |

5c |

15 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

|

VISN 6: Mid-Atlantic |

8 |

13 |

5 |

10 |

— |

|

VISN 7: Southeast |

9 |

31 |

3 |

9 |

0 |

|

VISN 8: Sunshine |

8c |

39 |

8 |

19 |

2 |

|

VISN 9: Mid-South |

9 |

30 |

6 |

11 |

0 |

|

VISN 10: Ohio |

5 |

29 |

3 |

6 |

0 |

|

VISN 11: Partnership |

8 |

23 |

22 |

9 |

0 |

|

VISN 12: Great Lakes |

7 |

0 |

33 |

9 |

0 |

|

VISN 13 and 14: now 23 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

VISN 15: Heartland |

9 |

42 |

1 |

7 |

0 |

|

VISN 16: South Central |

11 |

32 |

14 |

13 |

0 |

|

VISN 17: Heart of Texas |

7c |

18 |

11 |

9 |

0 |

|

VISN 18: Southwest |

7 |

41 |

1 |

14 |

0 |

|

VISN 19: Rocky Mountain |

6c |

37 |

2 |

14 |

0 |

|

VISN 20: Northwest |

9c |

26 |

1 |

15 |

2 |

|

VISN |

Hospitals and Medical Centers |

Community-Based Outpatient Clinics |

Other Outpatient Clinics |

Vet Centers |

Other Facilitiesb |

|

VISN 21: Sierra Pacific |

8 |

9 |

26 |

20 |

0 |

|

VISN 22: Desert Pacific |

5 |

29 |

5 |

11 |

1 |

|

VISN 23: Midwest |

12 |

40 |

3 |

14 |

0 |

|

Total |

170 |

576 |

144 |

251 |

6 |

|

aAs of April 10, 2009. bIncludes domiciliaries, federal hospitals, rehabilitation facilities, posttraumatic-stress-disorder clinics, and care facilities. cIncludes at least one VA health-care system in addition to the medical centers. SOURCE: IOM (2009). Adapted from VA (2009b). |

|||||

Veterans Affairs Medical Centers

The medical centers, in addition to providing clinical care for acute conditions, provide a variety of other programs specifically tailored to OEF and OIF veterans and their families, including polytrauma treatment, rehabilitation, postdeployment counseling, mental-illness programs, and education sessions (GAO, 2008c). Every medical center uses a care-management team, case managers, and transition patient advocates who help arriving OEF and OIF veterans to navigate through the VA health-care system and coordinate present and long-term care (VA, 2009k).

Vet Centers

The Vet Center Program, known formally as the Readjustment Counseling Service, was established by Congress in 1979 to provide services to Vietnam veterans who were still experiencing substantial readjustment challenges. Since then, vet-center eligibility has been extended to combat veterans of other conflicts, including most recently in 2003 to all OEF and OIF veterans and their family members and federally activated National Guard and reserve personnel. Vet centers are community-based nonmedical VA facilities that offer access to a broad array of social services for veterans and their families. Examples of services offered are individual and group counseling, marital and family counseling, medical referrals, assistance in applying for VA benefits, employment counseling and referral, alcohol and drug assessments, information regarding community resources, military sexual-trauma counseling and referral, and community outreach and education. Bereavement counseling is available for surviving family members of veterans who lost their lives while on active duty (VA, 2009l).

As of April 2009, there were 230 vet centers; they are located in every state, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the US Virgin Islands (VA, 2009d); 23 of the centers were added in 2007 and 20089 (Panangala, 2007), and VA plans to bring the total number to 299 by the end of 2010 (VA, 2009c). Most vet centers are staffed by one or two full-time counselors and are managed by a team leader who reports directly to one of the seven regional counseling-service managers, who in turn reports to the chief readjustment-counseling officer at VA headquarters (Panangala, 2007).

The committee heard anecdotal reports (see Appendix B) that OEF and OIF veterans view vet centers as places for older veterans, particularly from the Vietnam War, that are not equipped to meet the needs of the younger generations. To connect with returning troops better, starting in 2004 the vet centers hired 100 OEF and OIF veterans as outreach workers and have focused efforts on or near active military out-processing stations and at National Guard and reserve sites. Beginning in October 2008, VA also introduced a fleet of 50 mobile vet centers— 38-foot motor coaches that have spaces for confidential counseling—to supplement the existing vet centers and to expand service to veterans in geographically dispersed rural areas (VA, 2008b, 2009c). From the start of hostilities in 2001 through the end of 2008, vet centers received over 85,000 veterans for in-center visits and contacted an additional 260,000 at outreach events (Frame and Batres, 2009).

Disability Compensation and Survivor Benefits

The Disability Compensation Program provides monetary benefits to eligible veterans who were injured or exacerbated an injury during active duty; compensation amounts are based on individual disability ratings (from 10 to 100%) (VA, 2009m). As of March 31, 2009, 3 million veterans were receiving disability compensation, of whom 268,926 had a 100% disability rating; 69% of those who filed claims received service-connected–disability compensation (VA, 2009d). In addition, the Veterans Pension Program is offered to veterans who are over 65 years old or fully and permanently disabled because of active-duty service and whose family income is below a set threshold that is modified each year (VA, 2009n).

In an effort to expedite claims processing and to ensure that veterans are covered at time of discharge, VA offers a predischarge program, which allows service members to apply for disability compensation up to 180 days before discharge or retirement from active duty. In addition, on December 2008, VA began a 1-year program, implemented in 10 regional offices, called the Fully Developed Claim Pilot Program to test the feasibility of processing compensation, burial, and survivor benefits within 90 days of receiving a completed claim. In 2007, the average time for finalizing disability claims for OEF and OIF veterans was 110 days (VA, 2009d).

Surviving spouses and dependents are generally eligible for death pension benefits if family income does not exceed a specified amount. In addition, Dependency and Indemnity Compensation is a tax-free monthly paid benefit based on such factors as income and number of dependents. Numerous state benefits are also available and vary by geographic location. In addition, family members of deceased service members and veterans have access to such programs as the Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment Services, education assistance, Home Loan Guaranty, Vet Center Bereavement Counseling, and a life-insurance settlement (VA, 2009o).

The Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors (www.taps.org), founded in 1994, is the most comprehensive online resource for those dealing with the loss of a service member. Resources are provided in the form of pamphlets and publications, an online support community, seminars and other events, and information on finding regional support groups. Because of its partnership with VA, it also provides information on obtaining bereavement counseling at local vet centers.

Overview of Programs and Services for Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Active-Duty Service Members, Veterans, and Their Families

Since the start of OEF and OIF, the federal government has expanded programs and treatment facilities to focus specifically on the continuing care of service members who are severely wounded or injured or become ill while in theater. For example, the Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (DCoE) was created in 2007 in response to the growing prevalence of traumatic brain injury (TBI), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and other mental health problems in the military and veteran populations (www.dcoe.health.mil). Other centers that have been initiated include the Deployment Health Clinical Center, the National Center for Telehealth and Technology, the National Intrepid Center of Excellence, and the Center for Deployment Psychology. The goals of those centers are, respectively, to improve deployment-related health; to develop new technologies to prevent and treat people for psychologic health problems and TBI; to provide advance care and treatment for military personnel who have PTSD, complex psychologic health issues, or TBI; and to educate military and civilian behavioral health professionals about mental health needs peculiar to deployment. As noted earlier, this section does not provide a comprehensive list of all federally available programs, nor does it provide information on programs that are available at the state and local levels; rather, it highlights programs that are available to OEF and OIF service members, veterans, and their families through DOD, VA, and other federal agencies. It is subdivided by programs that provide long-term care and rehabilitation for physical needs, programs that provide mental health care, and programs for social needs.

Programs for Physical Needs

As described in Chapter 4, an increasing number of seriously wounded service members are returning from OEF and OIF. Those veterans have severe injuries—such as TBI, amputation, spinal-cord injury, and severe burns—and in some cases polytrauma. DOD and VA have expanded on and created programs to provide long-term care to treat and rehabilitate those severely wounded warriors.

In combat zones, medically trained military personnel administer immediate life-saving care to severely wounded service members until they can be evacuated to a forward surgical team, each comprising four surgeons. In Iraq and Afghanistan, the forward surgical teams have been deployed closer to the front lines than in past conflicts, and they provide emergency surgical intervention until casualties can be evacuated to a combat support hospital. From the combat support hospital, patients may be evacuated to one of three regional military hospitals in Kuwait, Spain, or Germany or in some cases evacuated directly to treatment facilities in the United States; MTFs that specialize in treatment of severely wounded service members include the Army’s Walter Reed Army Medical Center10 in Washington, DC, the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, and the Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas, which specializes in treatment for burns (Henning, 2007).

Wounded Warrior Support

Each service, in 2004–2005, has independently established its own Wounded Warrior Support Program. The programs conduct outreach to eligible severely injured and ill service members, who once enrolled are assigned case managers to assist them and their families through all phases of recovery, rehabilitation, and reintegration into active duty or civilian life (details of each program are presented below). A report from the Congressional Research Service has noted that DOD has not issued a directive or instruction to delineate responsibility among the services, coordinate complementary services, set eligibility criteria, or define standardized metrics to evaluate program effectiveness and identify overlaps, excesses, or gaps (Henning, 2007). However, several programs have been introduced to promote coordination or at least to provide other routes through which service members and their families can access care and services. For example, the Military Severely Injured Center (MSIC), established in 2005, staffs a 24-hour toll-free hotline for severely injured service members and their families (Henning, 2007). In addition, in 2008, Military OneSource (see discussion below)—which provides information and referrals to fully confidential nonmedical counseling sessions for individuals, couples, and families—launched the Wounded Warrior Resource Center (WWRC), which is accessible by e-mail, by telephone, and through the Military OneSource Web site. The MSIC and the WWRC do not replace or standardize service-specific wounded-warrior programs but rather serve as additional points of contact to help military families to connect with existing sources of care.

Army Wounded Warrior Program

The Army Wounded Warrior Program was established in 2004 as the Disabled Soldier Support System and has since been included as a component of the Army Family Covenant. The program provides individualized rehabilitation and recovery support to severely injured and ill soldiers and their families. Eligibility requires one of the following conditions: severe injury (such as an amputation) or paralysis; permanent and unsightly disfiguration (for example, of the face or hands); incurable, fatal disease and limited life expectancy; established psychiatric condition or release from service for a psychiatric condition; or another condition requiring extensive treatment or hospitalization (Army Regulation 40-400, March 12, 2001). Each program staff member advocates for about 30 wounded warriors, assisting them to secure benefits; navigate such potentially difficult issues as pay, promotion, and family travel; and deal effectively with the MEB, the PEB, and program offices in VA and the Department of Labor (DOL). The Army Wounded Warrior Program works closely with the Army Career and Alumni Program to encourage soldiers to continue on active duty (DOD Task Force on Mental Health, 2007; Henning, 2007).

Navy and Marine Corps Wounded Warrior Programs

The Navy Safe Harbor program was created in 2005 to provide assistance and support to severely injured sailors and their families, particularly those wounded in OEF and OIF. Eligibility extends to sailors who were seriously injured while shipboard or in accidents while on liberty, and it includes sailors who have serious illnesses, whether physical or psychologic. The program tracks all severely wounded, ill, and injured sailors and reaches out to eligible persons; nonmedical case managers are assigned to seven major MTFs and three VA polytrauma centers. Sailors enroll in the program for life or for as long as they have need of the services. Navy Safe Harbor representatives contact their charges at least once per month and connect enrollees and

their families to resources and services available for their particular needs. In addition, case managers help sailors to maintain contact with their commands and units. For sailors assigned to Marine Corps units, Navy Safe Harbor collaborates with Marine For Life (Task Force on Returning Global War on Terror Heroes, 2007). Enrollees in Safe Harbor average around 5,000–6,000, and about 350 sailors enrolled in 2008 (Watkins, 2008).

The Marine Corps Wounded Warrior Regiment was formed in 2007 through the consolidation of the Wounded Warrior Barracks at Camp Lejeune (created in 2004) and the Marine for Life Ill and Injured Support Section (2005). The Wounded Warrior Regiment provides and facilitates assistance to wounded marines, sailors attached to or in support of Marine Corps units, and their families throughout the recovery process; the stated mission is to ensure that every marine is able to transition back into his or her community successfully. The Wounded Warrior Regiment is headquartered at Quantico, Virginia, and battalions are at Camp Pendleton, California, and Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. The regiment provides non-medical care management, such as chaplains for spiritual support, liaisons to address VA benefit and transition issues, and job-transition support by a DOL professional (Marine Corps Wounded Warrior Regiment, 2009). The regiment Web site (www.woundedwarriorregiment.org) offers news, information, and useful links related to particular injuries, benefits, helpful organizations, and the recovery process, as well as issues that service members and their families may face along the way.

Air Force Wounded Warrior Program

The Air Force Wounded Warrior program (www.woundedwarrior.af.mil) provides information and resources to wounded, ill, and injured airmen and their families. The Wounded, Ill and Injured Compensation and Benefits Handbook (DOD and VA, 2008) is designed to help service members and their families to understand and take advantage of the services available to them. The Air Force Wounded Warrior program works hand-in-hand with the Air Force Survivor Assistance Program and the Airman and Family Readiness Centers to ensure support and care from the point of injury to at least 5 years after separation or retirement. The Air Force Wounded Warrior program also provides professional services—such as transition assistance, employment assistance, moving and financial counseling, and emergency financial assistance—and further coordinates benefit counseling and services provided by DOD and other agencies, such as VA, DOL, the Social Security Administration, and TRICARE.

Polytrauma System of Care

In addition to the medical centers and wounded-warrior programs provided by DOD, VA provides care to severely wounded service members and veterans through the Polytrauma System of Care (Table 5.2), which was created in 2004 (Henning, 2007). The Polytrauma System of Care provides different levels of rehabilitation services that are coordinated through a case manager. The case manager works with each service member and his or her family throughout the various phases of the stay and recovery to coordinate clinical care and consultations with psychologists and neuropsychologists and to create transparency regarding available services. As of April 2007, the system had treated over 350 inpatient OEF and OIF service members (VA, 2009f).

TABLE 5.2 Polytrauma System of Care

|

Level |

|

No. Locations |

|

1 |

Polytrauma rehabilitation centers |

4 |

|

2 |

Polytrauma network sites |

22 |

|

3 |

Polytrauma support clinics |

80 |

|

4 |

Polytrauma point of contact |

N/A |

|

SOURCE: Rehabilitation Outcomes Research Center (2007). |

||

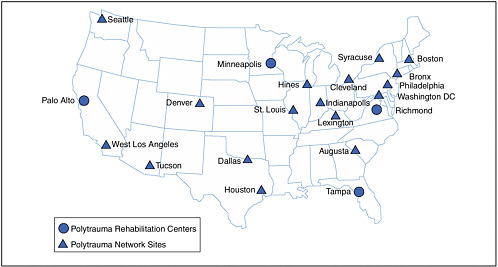

The four level 1 polytrauma rehabilitation centers (PRCs) (Figure 5.3) are in Palo Alto, Minneapolis, Tampa, and Richmond; a fifth is scheduled to open in San Antonio in 2011 (VA, 2009f). The PRCs are designed to coordinate the transfer of polytrauma patients from the MHS to VA and to provide continuing acute, comprehensive, and interdisciplinary inpatient rehabilitative care. VA social workers assigned to MTFs by the Office of Seamless Transition are responsible for maintaining communication between MTF and VA health-care providers during the transfer. Both VA case managers and military liaisons placed at each PRC assist with logistical arrangements for family members, and clinical psychologists are on hand to provide counseling, education, and other support services. The PRCs also have training apartments where rehabilitation staff members are available to prepare and inform family members about the needs and necessary adjustments for the home environment before patient discharge (VA, 2009f).

Since 2004, VHA has added 22 level 2 polytrauma network sites, at least one in each VISN (Rehabilitation Outcomes Research Center, 2007). Case managers at the sites provide continuing postacute care, manage existing and newly emerging conditions, and continue rehabilitation work after discharge from a PRC (VA, 2009f).

The third level of care consists of 80 polytrauma support clinics, which are staffed by teams of rehabilitation providers who manage the long-term effects of polytrauma through outpatient care and consultation; they also attend to followup home visits. The final level is the polytrauma point of contact, which provides continuing support to those who have stable treatment plans (Rehabilitation Outcomes Research Center, 2007).

FIGURE 5.3 Polytrauma facility locations (levels 1 and 2).

SOURCE: VA (2009p).

Programs for Mental Health Needs

As described in Chapter 4, a high prevalence of mental health issues in OEF and OIF service members and veterans is being reported. This section describes the programs and services that respond to that need. In particular, it describes DOD and VA programs directed at prevention and early identification of mental health problems (such as PTSD), substance abuse, and suicide prevention. DOD provides many independent programs and services, which are administered through multiple agencies and funding sources, to provide psychologic services to the military community. The result is a system in which military personnel can access help through multiple channels that are different but that often overlap. As the DOD Task Force on Mental Health (2007) noted, “non-centralization is in many ways a good thing: it promotes higher participation and awareness of mental health needs across DOD, and offers indirect avenues to care for those who may find more direct routes impractical or unpalatable.” The task force also notes, however, that “while the multiplicity of programs, policies, and funding streams provides many points of access to support for psychological health, they may also lead to confusion about benefits and services, fragmented delivery of care, and gaps in service provision” (DOD Task Force on Mental Health, 2007). To protect against those potential gaps in care, the task force reinforced the notion that maintaining psychologic readiness for the US fighting force requires DOD to provide mental health services across the full continuum of military life. To encompass that continuum, the task force envisioned a three-tier system of care (DOD Task Force on Mental Health, 2007): prevention, identification and intervention, and treatment and reintegration.

According to the task force, such a system would be more compassionate and economical than focusing solely on treatment for serious mental diseases after they have developed. However, to implement such a comprehensive mental health–care system successfully, DOD

must address two major barriers: wide geographic dispersion and frequent transitions make it difficult for many service members and their families, especially in the National Guard and reserve components, not only to learn about and access care but to complete treatment that requires many clinical visits over an extended period; and the stigma commonly associated with accessing mental health care continues to prevent many service members from seeking help (DOD Task Force on Mental Health, 2007).

In response to the increasing need for and to overcome those obstacles to care, DOD has expanded its capacity and introduced new programs. To address the growing prevalence of TBI, PTSD, depression, and other psychologic problems, DOD created the DCoE in 2007. Nine directorates and six centers are under the umbrella of DCoE, encompassing clinical care, education and training, prevention, research, and outreach to military personnel, veterans, and their families and communities (www.dcoe.health.mil). Through the DCoE and other offices, DOD is pursuing several strategies, including integrating mental health services into primary care, embedding mental health professionals in units in theater, raising awareness about mental health disorders in the military community, and running marketing campaigns to promote a healthier, more accepting attitude toward mental health problems and treatment.

Combating Stigma

The Deployment Health Clinical Center in the DCoE oversees the RESPECT-Mil program—Re-Engineering Systems of Primary Care Treatment in the Military. The program targets the primary-care setting as an opportunity to bring access to mental health care to a larger proportion of service members (Engel et al., 2008). For example, Army soldiers visit their primary-care provider an average of 3.4 times per year, and about 90% have at least one visit per year (Engel, 2009).

RESPECT-Mil uses the Three Component Model of care (Engel, 2009; Engel et al., 2008; Oxman et al., 2002), which provides the infrastructure for coordination among each service member’s primary-care provider and mental health specialist through a facilitating care manager. The care managers are responsible for facilitating communication between the service member and all care providers, problem-solving barriers to care, encouraging adherence to treatment guidelines, measuring treatment response, and monitoring the service member for remission. In addition, primary-care providers undergo a 2-hour Web-based training session in which they learn brief screening techniques for PTSD and depression and how to use tools provided by RESPECT-Mil to facilitate communication with care managers and mental health specialists and ensure a higher rate of followup.

The Army has implemented RESPECT-Mil in over 30 Army clinics and has plans to staff a total of 43 (provided by the Department of the Army in response to committee request, August 31, 2009). From the start of the program in February 2007 to May 2009, primary-care providers in participating Army clinics screened 62% of over 400,000 total visits compared with 5% or less in nonparticipating teaching clinics. About 14% of patients screened positive, and 60% of the positively screened received a diagnosis of depression or possible PTSD. In total, the Army Medical Command estimates that nearly 3% of all visits resulted in recognition of and assistance for previously unrecognized behavioral health needs (Department of the Army, 2007). The program is limited to Army facilities, but expansion to the other services is in the planning stages (RESPECT-Mil, 2010). The program operates on the premise that merging mental health care

with primary care will increase the use of mental health services and help to reduce stigma (Department of the Army, 2007).

Parallel to the Army’s efforts to integrate mental health into primary care, the Air Force’s Behavioral Health Optimization Project (BHOP), which began in 1999 and expanded substantially over the last 2 years, integrates behavioral health providers into primary-care clinics in 53 MTFs. Primary behavioral health care relies on brief appointments that are focused on functional assessments and level-of-care determinations. Through BHOP, behavioral health consultation services are provided to active-duty and retired military personnel and their family members in primary-care clinics, where mental health providers deliver both curbside consultation and direct patient care when indicated. This care typically entails brief, empirically supported interventions, primarily targeting self-management and behavioral prescriptions. Twenty contract BHOP positions were authorized in 2008 to expand the program. Thirty-two providers received BHOP training during 11 site visits in 2009; another nine site visits were scheduled to take place by the end of FY 2009 (provided by the Department of the Air Force in response to committee request, June 10, 2009).

The Marine Corps and Army have also begun to integrate mental health professionals into individual units in theater, with the goal of providing more immediate mental health care and identifying potential mental health issues as early as possible. The goals are to help commanders to build unit strength, resilience, and readiness and to provide prevention, early identification, and intervention services to soldiers, marines, and sailors for stress-related problems. The general assumptions seem to be that troops in the field will be more comfortable in talking with members of their own unit and that this might help to avoid the stigma that deters many service members from seeking help for mental health problems (provided by the Department of the Army in response to committee request, August 31, 2009, and the Department of the Navy, September 10, 2009).

The Operational Stress Control and Readiness (OSCAR) program augments the Marine Corps Combat and Operational Stress Control program by embedding full-time mental health professionals at the infantry regiment level. They deploy with their units in theater and stay with them when they return to garrison. Full staffing of OSCAR teams is in progress, and completion is projected for FY 2011. Until then, the Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery plans to fill OSCAR teams for deploying units with available mental health personnel on an ad hoc basis. The Marine Corps also uses existing medical, chaplain, and fighting personnel in the battalions and companies to function as peer mentors, effectively extending OSCAR functionality to units smaller than the regiment. They are selected and trained to perform OSCAR duties appropriate to their expertise and experience (provided by the Department of the Navy in response to committee request, September 10, 2009). Similarly, the Army has developed the Combat and Operational Stress Control (COSC) program. The Army believes that it has increased stress control in theater since the beginning of the war with the deployment of behavioral health professionals. An additional field manual published in 2009 (FM 6-22.5) provides leader guidance in executing the COSC program, and a course in COSC is now required of all deploying behavioral health providers (provided by the Department of the Army in response to committee request, August 31, 2009).

The Real Warriors Campaign, launched by the DCoE in May 2009, “combats the stigma associated with seeking psychological health care and treatment and encourages service members to increase their awareness and use of these resources” (Real Warriors Campaign,

2009). The Real Warriors Campaign presents profiles and stories, including video, of service members, veterans, and military families that have been through the experience of seeking treatment for mental health problems, including PTSD and depression. By sharing true experiences of service members who have sought and received mental health services, the DCoE hopes to demonstrate to other service members that seeking mental health treatment and accessing the tools and resources available are acceptable and in some cases vital elements of successful recovery and reintegration.

The campaign is run primarily through the Real Warriors Web site (www.realwarriors.net), which links to information for active-duty personnel, National Guard and reserve members, veterans, family members, and health professionals. Service members can enter a live chat with a health-resource consultant either through the Web site or by calling a toll-free telephone number; a link to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, with a telephone number, is also prominently displayed on the site’s home page.

Even with such programs as RESPECT-Mil and OSCAR and campaigns promoting the benefits of mental health care in place to provide some safeguards to service members seeking it, stigma among military personnel remains. The Navy and Marine Corps state that “stigma over seeking help for stress problems is also a significant issue” (provided by the Department of the Navy in response to committee request, September 10, 2009). The committee heard from active-duty military personnel and from OEF and OIF veterans that they are not willing to seek professional help for problems related to mental health. One major reason that has been stated is that it would be a “stripe killer” (see Appendix B). That fear is not limited to enlisted personnel: the committee heard during site visits that officers may be even more reluctant to obtain mental health care because of their concern about obtaining a security clearance if they disclose having ever received such care. However, in May 2008, Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates announced a change in question 21 on the national security clearance questionnaire (SF-86); the question now excludes counseling related to service in combat.

In addition to the programs described above, military chaplains are available to every military unit for nonclinical counseling and serve as the first point of access for many individuals (DOD Task Force on Mental Health, 2007; Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008). Military chaplains serving as noncombatant officers provide spiritual and moral support to service members and their families. Chaplains refer service members to other sources of care and often assist with military health programs, such as those for suicide prevention. Consultation with a chaplain is confidential, and it has been suggested that this type of informal, nonclinical counseling can be viewed as a safe first source of care for service members in distress, especially those who might have mental health issues and are concerned about stigma (DOD Task Force on Mental Health, 2007; Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008).

Mental Health–Disorder Prevention

The Army developed the Battlemind Training System to teach soldiers better mental health skills and to improve their resilience in the presence of combat stress and reduce their vulnerability to PTSD, depression, and other deployment-related mental health problems. The training builds mental health skills through a series of integrated modules timed to the specific phases of the soldiers’ career and deployment cycle. For example, the Battlemind deployment-cycle training consists of predeployment modules to improve health readiness, in-theater Battlemind psychologic debriefings to maintain mental health and identify possible problems

during deployment, and additional modules at reintegration and 3–6 months after deployment. The Army reports that the efficacy of Battlemind training has been validated in large-scale randomized trials (Office of the Surgeon Multinational Force–Iraq and Office of the Surgeon General United States Army Medical Command, 2008).

Because of the perceived success of Battlemind deployment-cycle training, the Army has introduced a version in basic training with the goal of instilling proven stress-management skills in soldiers at the beginning of their careers. Optional Battlemind modules for spouses and couples are also provided before and after deployment with the aim of increasing marital satisfaction and decreasing deployment stress. Additional modules, such as interactive content for military children, are available on the Battlemind Web site (www.battlemind.army.mil) (information provided by the Department of the Army in response to committee request, August 31, 2009).

Substance-Abuse Prevention and Treatment Programs

As described in Chapter 4, although data suggest that alcohol and drug abuse or dependence is probably prevalent in OEF and OIF service members and veterans, it is underreported. Active-duty service members who abuse alcohol or drugs are at risk for dishonorable discharge, so there may be under-reporting of abuse of such substances and minimal treatment-seeking. On the basis of DOD policy, the services can periodically assess the extent of alcohol and drug abuse in active-duty military personnel through their drug-testing programs (DOD Directive 1010.4, September 3, 1997, with Change 1, January 11, 2009); however, it is not clear whether the services monitor the numbers of members who have substance-abuse problems or whether they are referred to treatment programs. According to information available in government documents, each service in DOD manages its own substance-abuse prevention and treatment programs (DOD Task Force on Mental Health, 2007). The Army and Air Force run programs that provide both substance-abuse prevention and treatment services, whereas the Navy and Marine Corps split their substance-abuse services into separate programs for prevention and treatment.

VA provides substance-abuse screening and treatment programs for veterans who are dealing with addiction to or misuse of alcohol, drugs, or tobacco (http://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/substanceabuse.asp). Program options on the state and community levels vary and include inpatient and outpatient services and individual or group therapy and counseling; distribution of such medications as nicotine-replacement therapy, varenicline for nicotine addiction, and methadone for chronic opiate addiction. The focus may be on treatment for comorbid conditions, such as depression and PTSD (VA, 2009e).

Suicide Prevention

Each military service manages its own suicide-awareness and suicide-prevention program. Generally, the programs focus on education and on identifying people who are at high risk. For example, the Air Force Suicide Prevention Program seeks to use policy, programs, and education initiatives to reduce suicide in airmen. The Air Force program uses an integrated system of 11 initiatives that target key policies, programs, and populations considered essential for suicide prevention (Air Force Pamphlet [AFPAM] 44-160, April 2001). It focuses on identifying and intervening with airmen who are at risk for suicide, and all airmen (military and civilian) are trained in risk recognition and intervention techniques.

The Army has also made a concerted effort to improve suicide prevention. The Army Suicide Event Report system continues to offer surveillance and analysis, and the Army Medical Department has created a new Suicide Prevention Office to translate the results into further education and training for mental health practitioners, leaders, soldiers, and their families. One result has been the publication of the Army Campaign Plan for Health Promotion, Risk Reduction and Suicide Prevention (provided by the Department of the Army on request by the committee, August 31, 2009).

Like DOD, VA has established suicide-prevention programs. In November 2004, the Mental Health Strategic Plan called for numerous initiatives to prevent suicide in veterans. As a consequence, VA implemented such prevention programs as the National Suicide Prevention Center of Excellence, appointed a national suicide prevention coordinator, and began flagging patient medical records and establishing suicide-prevention programs in each facility and large community-based outpatient clinics, which have appointed full-time suicide-prevention coordinators. Evaluation of those initiatives in 2009 showed that overall compliance goals were met and program implementation was satisfactory (VA Office of the Inspector General, 2009).

The Joshua Omvig Veterans Suicide Prevention Act (PL 110-110), signed into law in November 2007, called for VA to establish a comprehensive suicide-prevention program with emphasis on decreasing the incidence of suicide in veterans at high risk, such as those who have PTSD or depression. The act requires VA to have 24-hour mental health care available, to establish a 24-hour suicide-prevention hotline, and to place a suicide-prevention coordinator in each VACM; by September 2008, there were 148 suicide-prevention coordinators—at least one in each VAMC (Cross, 2009; Panangala, 2007).

Veteran Chat, launched as a pilot trial in July 2009, is an anonymous on-line suicide-prevention hotline available for veterans, families, and friends; one does not need eligibility or enrollment in VA health care to use this program. If a call is deemed to indicate a crisis, the caller is transferred to the hotline where suicide prevention counselors provide further intervention (VA, 2009q).

Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

In light of the increasing mental health–care needs of OEF and OIF veterans, VA has expanded on and developed numerous screening and treatment programs for PTSD. For example, it has implemented mandatory screening of all veterans for PTSD and TBI on their first visit to any VA facility. In addition, vet centers, which have historically provided counseling for Vietnam veterans, are taking measures to attract the current generation of veterans and their families. In general, the mental health–care and social programs provided vary widely, and the array of services depends on location and facility type.

VA sponsors over 200 outpatient and inpatient PTSD-treatment programs and trauma centers in VAMCs, community-based outpatient clinics, and vet centers that provide a variety of treatment, counseling, and support; below are examples of implemented programs at VAMCs (Box 5.2) (VA, 2009r).

|

BOX 5.2 VA PTSD Programs

SOURCE: Adapted from VA (2009r). |

VA also sponsors the National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; its Web site (www.ncptsd.gov) educates veterans and their family members on PTSD-related issues and offers guidance on how to find local therapists and support groups. Although not particular to OEF and OIF veterans, this additional source provides information on the illness and access points for treatment.

Programs to Meet the Social Needs of Service Members, Veterans, and Their Families

As discussed in Chapter 4, service members returning from Iraq and Afghanistan also face non-health-related challenges and need assistance in readjusting to life outside the war zone, which can include educational, financial, legal, and employment-related support. Although the VBA is designed to meet much of the need for assistance with social readjustment for veterans and to include some benefits for their survivors (such as funeral costs), the individual services also offer support networks that include peer counseling, advising, employment programs, and family-support programs. It is worth noting that numerous states and nongovernment organizations also provide assistance to service members, veterans, and military family

members, but it is beyond the scope of this report to discuss all these efforts; some programs provided by federal agencies are described below.

Family Programs

Military families receive counseling, information, and other support from a broad array of sources. The Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Military Community and Family Policy issues centralized policies that establish broad baselines for how the military should support its families, and further policies are issued at the service level. Implementation occurs largely at the discretion of individual installation commanders. Furthermore, many bases establish close relationships with local communities to augment family support; for example, bases collaborate with local “military-impacted” school systems through liaison officers to arrange education for dependents or to provide additional employment assistance for spouses and separating service members. The effects of commander discretion and the unique collaborations that develop between an installation and its community mean that the systems of support to which military families can turn to for help vary widely, depending on their service branch and geographic location.

Each branch offers programs that provide support to service members and their families, addressing needs that include deployment readiness and reintegration, financial management, new-parent support, employment, education, relocation assistance, counseling, and support in moving back to civilian life. Programs offered through the Air Force family-services office are briefly highlighted below (provided to the committee by the Department of the Air Force, June 10, 2009); it should be noted that these programs are comparable with those offered by the Navy, Marine Corps, and Army. The Air Force program, called the Airman and Family Readiness Flight, is available at each Air Force installation and manages airman and family readiness centers, youth programs, child development centers, and family child-care programs on bases. The services are available to active-duty, Air National Guard, Air Force reserve, and geographically dispersed service members and their families. Final implementation of the programs falls at the discretion of base commanders, but military family-support programs generally include

-

Deployment readiness and sustainment—includes mandatory predeployment briefings and sustainment services for waiting families.

-

Reintegration support—as airmen return from deployment, reintegration briefings are provided to inform them of support services; preparation for families is provided at home station and at followup throughout the reintegration process.

-

Transition-assistance program—preseparation counseling is mandated by law for all separating and retiring military; the Air Force supplements this counseling with a variety of workshops that focus on job-search skills and assistance to families during transition.

-

Military child education—support is provided by senior wing leaders who attend school-board meetings and advocate for the interests of military families; Airman and Family Readiness Flight staff supplement the support with information, referral, and resources for parents.

-

Personal financial-management program—financial-readiness services are delivered through one-on-one counseling, classes, and media; the current focus includes assisting with bankruptcy and foreclosure.

-

Emergency family-assistance control centers and crisis response—at the request of the commander, Airman and Family Readiness Flight centers set up and serve as a staging area where families can obtain disaster-relief and contingency information and services.

-

Personal-life and work-life education services—include prevention/enrichment education and consultation for individuals, couples, and families.

-

The Air Force Aid Society Partnership—assists airmen and families as financial emergencies occur; in addition, community-enhancement programs supplement child care, educational needs, and deployment support of family members.

-

Relocation-assistance program—includes relocation information and education, including predeparture and postarrival services.

-

Employment-assistance services—help to meet the challenges that spouses face in training for and finding suitable positions; the focus is on assisting in training for and continuing in portable careers that can move with the spouse as the family relocates.

-

Volunteer resources—Airman and Family Readiness Flight centers collaborate with other base agencies to recruit, train, place, and recognize volunteers across the installation.

-

Key spouse program—a family-readiness network that recruits family-member volunteers, usually spouses, to serve as peer-to-peer advisers and liaisons with base leadership; first introduced in a test phase in 1996 and standardized across the Air Force in March 2009.

The Military and Family Life Consultant (MFLC) program delivers short-term, situational, problem-solving nonmedical counseling services to active-duty service members, including those in the National Guard and reserves, and their families who are experiencing trouble in coping with concerns and issues of daily military life (MHN Government Services, 2009). MFLCs are subcontracted licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, licensed marriage and family therapists, or psychologists; they provide six free informal and confidential counseling sessions per service member per issue, and no records are kept. The primary role of an MFLC is to provide supplemental support, assessment, and referral service, so the program emphasizes flexible appointment times and locations. Service members can access MFLCs on their installation without a referral, whereas service members and families not on an installation can contact Military OneSource to identify the MFLC that is closest to their location. The program was first piloted in 2004 with a limited population and later extended to all services in the United States, Europe, and the Pacific Rim (provided to the committee by the Department of the Army, August 31, 2009).

In 2008, DOD expanded the MFLC program to include personal financial counseling. Personal financial-counseling services include assistance with money management, credit and debt liquidation, analysis of assets and liabilities, and establishing and building savings plans. Contracted certified personal financial counselors help service members and their families to develop realistic spending plans, reduce debt, and save for their future needs and goals (MHN Government Services, 2009).

DOD oversees 800 child-development centers on military installations worldwide. The centers offer a safe child-care environment for children 6 weeks to 12 years old. The centers are generally open Monday through Friday from 6:00 a.m. to 6:30 p.m., but specific hours are subject to the discretion of the installation commander. DOD also oversees the Family Child Care programs, which offer in-home care by providers that are recruited and certified by the installation. Family Child Care helps to bridge gaps in child care when the child-development centers do not entirely meet the child-care needs of the family. Family-service centers, youth

centers, referral offices, and child-development centers have lists of approved homes and providers (MilitaryHOMEFRONT, 2009).

An additional component of military child care is the School Age Care program. School Age Care meets the needs of children 6–12 years old and provides before and after school care and summer and holiday programs. Additional support for families that have children over 12 years old can be found through the youth and teen programs often sponsored by youth services and community centers (MilitaryHOMEFRONT, 2009).

The services have in many cases set up partnerships with national and local nonprofit organizations, often at the local installation level, to broaden the array of child-care options available to military parents. For example, one Air Force program, Give Parents a Break, was created to provide eligible parents with a break from the stresses of parenting for a few hours each month. Air Force partners with the Air Force Aid Society, a national nonprofit organization, to provide child care at no cost to parents who are subject to unique stresses because of the nature of military life—deployments, remote tours of duty, and extended hours (provided to the committee by the Department of the Air Force, June 10, 2009).

Military parents living off base and in remote locations, especially members of the National Guard and reserves, are often eligible for programs that offer in-home child-care assistance. For example, the Air Force Home Community Care program provides over 57,000 hours of free care to Air National Guard and Air Force reserve families at locations near their duty sites and provides free, in-home child care during drill weekends. Other programs, such as Military Child Care in Your Neighborhood, meets child-care needs for remote active-duty military families by providing a direct subsidy (provided to the committee by the Department of the Air Force, June 10, 2009).

The services also offer a Family Advocacy Program to prevent, identify, report, treat for, and follow up on cases of child and spousal abuse in families of service members (DOD Task Force on Mental Health, 2007). The Family Advocacy Program operates at all stages of the deployment cycle and generally includes early-childhood development education, interactive play groups, parenting education, communication-skills training for couples and families, family-violence prevention training for leaders, consultation with leaders and service providers, and family advocacy strengths-based therapy, which offers professional intervention to families that are in crisis or at risk. Each service manages its own aspect of the Family Advocacy Program. For example, 79 Family Advocacy Programs are on Air Force bases worldwide, and 7,000–10,000 family maltreatment cases are assessed each year. Outreach and prevention services touch an additional 20,000–50,000 airmen and family members (provided to the committee by the Department of the Air Force, June 10, 2009).

Numerous sources of counseling and advice on a wide array of topics—including stress, substance abuse, employment, financial and legal advice, marriage, and child care—are available to family members of military personnel and veterans. National Web-based programs, such as Military OneSource (see below), provide easily accessible and free assistance to any military family that has an Internet connection. In addition, many alternate services available to service members, such as chaplains, provide counseling and advice to family members. For example, chaplains have taken a leadership role in supporting healthy marriages and family life. Such long-run family-enrichment programs as the Army’s Strong Bonds program (www.strongbonds.org)—which has been expanded to include components targeted at couples,

families with children, and even single soldiers—are slowly becoming widespread across the military community; over 160,000 people participated in the Strong Bonds program in 2008.

Education Programs and Benefits11

One of the benefits of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944—commonly known as the GI Bill—is education. Reworked by Congressman Montgomery of Mississippi in 1984, the Montgomery GI Bill Active Duty program provides an education-benefits package that may be used during active duty or after separation. Persons who first entered active duty after June 30, 1985, are generally eligible under the Montgomery GI Bill. Benefits cover 36 months of education and must be used either within 10 years after discharge from active duty or by November 2, 2010 (VA, 2009b). In 2008, Congress passed the Post-9/11 GI Bill (US Code, Title 38, Chapter 33), which provides education benefits for people who served on active duty after September 10, 2001. Beginning August 1, 2009, under that program eligible service members and veterans can receive educational benefits for tuition and fees, a monthly housing allowance, and a yearly stipend for books and supplies. In addition, eligible active-duty members can apply to transfer their education benefits to spouses or dependents through the DOD Transfer of Entitlement option (VA, 2009a). Similarly, the Survivors’ and Dependents’ Educational Assistance Program offers a maximum of 45 months of education benefits to eligible dependents and spouses of veterans who died while on active duty or who have permanent and total disability (http://www.gibill.va.gov/pamphlets/ch35/ch35_pamphlet_general.htm, accessed on September 30, 2009). Vocational-education counseling is available to inform veterans and their families about education options, specifically regarding the details of the recent GI Bill; the program is available for transitioning service members within 6 months to 1 year after discharge (http://www.vba.va.gov/bln/vre/vec.htm; accessed on September 30, 2009). In general, depending on length of active-duty service from 90 days to 36 months, benefit coverage ranges from 40% to 100%; people who served at least 30 days and were discharged with a service-connected disability are also eligible to receive benefits at the 100% level.

VA also administers a benefits package for reserve and National Guard members who signed 6-year commitments with a reserve unit after June 30, 1985, and remain active and in good standing with their units. The Montgomery GI Bill–Selected Reserve (Chapter 1606) is funded and managed by DOD. The benefit covers 36 months of education to be used within 14 years (VA, 2009a). In addition, the Reservists Education Assistance Program was created as part of the Ronald W. Reagan National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2005. The benefits (Chapter 1607) are available for reserve and National Guard members who were activated under federal authority for a contingency operation and served 90 continuous days or more after September 11, 2001.

Employment and Training Services