2

OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM AND OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM: DEMOGRAPHICS AND IMPACT

Since the beginning of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001, over 1.9 million US military personnel have been deployed in 3 million tours of duty lasting more than 30 days as part of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) or Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) (Table 2.1). Those wars are fundamentally different from the first Gulf War and other previous wars (see Chapter 3) in their heavy dependence on the National Guard and reserves and in the pace of deployments, the duration of deployments, the number of redeployments, the short dwell time between deployments, the type of warfare, the types of injuries sustained, and the effects on the service members, their families, and their communities. Moreover, OEF and OIF together make up the longest sustained US military operation since the Vietnam War, and they are the first extended conflicts to depend on an all-volunteer military. This background chapter is divided into three sections. The first provides information about the demographics of the all-volunteer military. The second highlights some of the issues faced by the troops who have served in OEF or OIF and their families that are being reported in the popular press, government reports, and the peer-reviewed scientific literature. On the basis of available data, it is not known whether those issues are causally related to deployment, but the challenges confronting the troops and their families appear to be real, and Chapter 4 describes them in greater detail. The third section of this chapter provides a brief summary of the services that are available to meet readjustment needs of OEF and OIF service members, veterans, and their families when they return from theater. Chapter 5 describes in more detail the benefits and services and the programs that have been developed to meet those needs.

TABLE 2.1 Service Members Deployed by Component as of April 30, 2009

|

|

Army |

Navy |

Air Force |

Marine Corps |

Coast Guard |

TOTAL |

|

Active component |

582,733 |

320,140 |

269,220 |

209,175 |

3,539 |

1,384,807 |

|

National Guarda |

239,336 |

N/A |

65,295 |

N/A |

N/A |

304,631 |

|

Reserves |

125,595 |

33,891 |

38,056 |

37,602 |

228 |

235,372 |

|

Total |

947,664 |

354,031 |

372,571 |

246,777 |

3,767 |

1,924,810 |

|

aIn contrast with the Army and Air Force, the Navy and Marine Corps do not have a National Guard component. SOURCE: Defense Manpower Data Center, 2009b. |

||||||

DEMOGRAPHICS OF THE ALL-VOLUNTEER MILITARY

Of the military personnel serving in OEF and OIF, 89% are men and 11% women. Nearly all troops who served in Vietnam were men (only 7,494 women served) compared with over 200,000 women serving in OEF and OIF (Jacobs, 2000; Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008). Today’s service members are also somewhat older1 and more likely to be married than their Vietnam-era counterparts (Jacobs, 2000). The distribution of personnel ages varies among components of the military. According to the 2007 Demographics Report, over 40% of active-component officers are over 35 years old compared to 15% of active-component enlisted personnel (DOD, 2007). The numbers of active-component officers and enlisted members by age and service branch are summarized in Table 2.2. Members of the Marine Corps have the lowest average age, 25.0 years, and the Air Force has the highest, 29.6 years. The reserve-component officers and enlisted members are much older than the active-component officers and enlisted members, respectively (DOD, 2007). Among reserve-component officers, 73.6% are over 35 years old compared with 44.2% of active-component officers. Similarly, 55.3% of the reserve-component enlisted members are 30 years old or younger compared with 72.6% of the active-component enlisted members. Table 2.3 summarizes the numbers of reserve-component officers and enlisted personnel by age group and service branch.

TABLE 2.2 Percentage of Active-Component Members by Age and Service Branch in 2009

|

|

Army (N = 582,733) |

Navy (N = 320,140) |

Air Force (N = 269,220) |

Marine Corps (N = 209,175) |

Total DOD (N = 1,381,268)a |

|||||

|

Age (Years) |

Officers (N = 82,228) |

Enlisted (N = 500,505) |

Officers (N = 38,106) |

Enlisted (N = 282,034) |

Officers (N = 46,615) |

Enlisted (N = 222,605) |

Officers (N = 18,873) |

Enlisted (N = 190,302) |

Officers (N = 262,680) |

Enlisted (N = 1,195,446) |

|

<20 |

0 |

6.7 |

0 |

5.8 |

0 |

2.6 |

0 |

7.0 |

0 |

5.8 |

|

20–24 |

5.8 |

43.9 |

7.0 |

45.9 |

3.5 |

39.1 |

5.9 |

65.6 |

7.6 |

47.0 |

|

25–29 |

21.0 |

23.0 |

25.3 |

19.2 |

26.2 |

24.5 |

29.1 |

15.4 |

26.2 |

21.2 |

|

30–34 |

20.5 |

12.0 |

22.0 |

12.0 |

24.8 |

12.6 |

26.2 |

6.0 |

22.4 |

11.1 |

|

35–39 |

21.5 |

9.2 |

20.4 |

10.9 |

20.1 |

12.5 |

21.4 |

4.0 |

20.4 |

9.4 |

|

40–44 |

17.1 |

3.9 |

15.7 |

4.5 |

15.8 |

7.2 |

11.6 |

1.5 |

14.5 |

4.3 |

|

45–49 |

8.6 |

1.0 |

6.9 |

1.3 |

6.8 |

1.5 |

4.0 |

0.4 |

6.2 |

1.1 |

|

50–54 |

3.7 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

0.1 |

1.4 |

0 |

2.0 |

0.2 |

|

≥55 |

1.8 |

0 |

0.6 |

0 |

0.5 |

0 |

0.4 |

0 |

0.7 |

0 |

|

aTotal numbers do not include the US Coast Guard. The Coast Guard is part of the armed forces but during peacetime is under the authority of the Department of Homeland Security rather than DOD. During wartime, the Coast Guard is under the authority of DOD through the Department of the Navy. About 4,000 members of the Coast Guard have been deployed to OEF or OIF (see Table 2.1). SOURCE: Defense Manpower Data Center, 2009b. |

||||||||||

TABLE 2.3 Percentage of Active-Component Members by Age and Service Branch in 2009

|

|

Army National Guard (N = 239,336) |

Army Reserve (N = 125,595) |

Navy Reserve (N = 33,891) |

Marine Corp Reserve (N = 37,602) |

Air National Guard (N = 65,295) |

Air Force Reserve (N = 38,056) |

Total Reservea (N = 539,775) |

|||||||

|

Age (Years) |

Officers (N = 25,852) |

Enlisted (N = 213,484) |

Officers (N = 23,655) |

Enlisted (N = 101,940) |

Officers (N = 6,811) |

Enlisted (N = 27,080) |

Officers (N = 3,429) |

Enlisted (N = 34,173) |

Officers (N = 8,892) |

Enlisted (N = 56,403) |

Officers (N = 48,8219) |

Enlisted (N = 29,837) |

Officers (N = 76,858) |

Enlisted (N = 462,917) |

|

<20 |

0 |

4.4 |

0 |

4.5 |

0 |

0.5 |

0 |

4.9 |

0 |

0.9 |

0 |

0.4 |

0 |

3.6 |

|

20–24 |

3.4 |

30.0 |

1.0 |

32.1 |

0.1 |

10.6 |

0.1 |

58.1 |

0.1 |

16.6 |

0.1 |

11.5 |

1.5 |

28.6 |

|

25–29 |

12.9 |

19.0 |

7.5 |

20.8 |

3.0 |

13.5 |

6.6 |

24.7 |

5.7 |

16.2 |

5.4 |

14.8 |

8.5 |

18.9 |

|

30–34 |

18.6 |

13.4 |

13.3 |

12.5 |

12.3 |

18.5 |

21.0 |

7.2 |

16.0 |

13.8 |

15.0 |

13.5 |

15.8 |

13.1 |

|

35–39 |

25.6 |

13.4 |

21.0 |

11.6 |

27.8 |

24.3 |

28.7 |

2.9 |

24.8 |

16.6 |

21.3 |

18.0 |

24.0 |

13.5 |

|

40–44 |

20.3 |

10.0 |

23.4 |

9.4 |

27.0 |

19.1 |

23.3 |

1.4 |

26.4 |

15.4 |

26.0 |

18.4 |

23.3 |

11.0 |

|

45–49 |

10.0 |

5.4 |

17.0 |

5.4 |

17.1 |

8.5 |

14.2 |

0.5 |

16.0 |

10.0 |

18.2 |

12.0 |

14.6 |

6.2 |

|

50–54 |

5.5 |

2.8 |

10.0 |

2.5 |

9.0 |

3.6 |

5.0 |

0.1 |

7.5 |

6.6 |

9.9 |

7.6 |

7.9 |

3.3 |

|

≥55 |

3.7 |

1.4 |

6.8 |

1.2 |

3.6 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

0 |

3.4 |

3.8 |

4.2 |

3.9 |

4.5 |

1.7 |

|

aTotal numbers do not include Coast Guard reserve. SOURCE: Defense Manpower Data Center, 2009b. |

||||||||||||||

Of service members serving in OEF and OIF, about 66% are white, 16% black, 10% Hispanic, 4% Asian, and 4% other race (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, 2009) compared with 75% white, 12% black, 4% Asian, 9% other race, and 12.5% Hispanic of any race in the general population (US Census Bureau, 2000). During the Vietnam War, of the roughly 3.4 million service members who were deployed (one-third of them through the draft), close to 90% were white (Summers, 1985).

Marital status also differs somewhat by component and service branch. Of the active-component force, 55.2% are married (DOD, 2007); the Air Force has the highest proportion of married members, 60.6%. Senior enlisted and senior officers are also more likely to be married. In addition, 6.7% of active-component military personnel are reported to be married to other military personnel (dual-military marriages); again, the Air Force has the highest percentage, 12.8% (DOD, 2007). A higher percentage of female military personnel is in dual-military marriages than males: over 26% of female Marine Corps members and 30% of female Air Force members are married to members of the military. In the most recent DOD demographic report, about 3% of those who indicated that they were married in 2006 were divorced in 2007.

Among the reserve-component members, 49% are married. The proportion of members reporting to be married varied by service component: the Air Force reserve reported the highest percentage, 60.6%, and the Marine Corps reserve the lowest, 30.8%. As in the active component, senior enlisted and senior officers were more likely to be married (DOD, 2007).

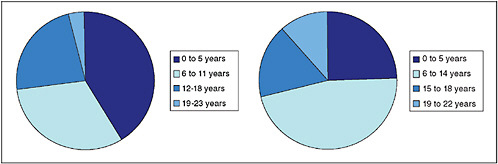

Some 43% of active-component members have children, two on the average.1 Similarly, reserve-component members who have children have an average of two. The breakdowns of active-component and reserve-component members with children by service branch are summarized in Table 2.4. About 5% of active-component members are single and have children. (In comparison, according to the US Census, 17% of US households were single-parent households in 2007.) In addition, another 3% are dual-military with children. The largest percentage of minor dependents of active-component members is 5 years old and younger (41%); in the reserve component, the largest percentage is children 6–14 years old (DOD, 2007). The distributions are shown in Figure 2.1.

TABLE 2.4 Active-Component Members with Children by Service Branch in 2007

|

|

Army |

Navy |

Air Force |

Marine Corps |

Totala |

|

Active component |

241,704 (46.7%) |

141,108 (42.5%) |

150,008 (45.6%) |

55,923 (30.0%) |

588,743 (43.1%) |

|

National Guardb |

140,244 (39.8%) |

N/A |

51,743 (48.7%) |

N/A |

191,987 (41.6%) |

|

Reserves |

75,797 (39.9%) |

35,683 (51.0%) |

36,024 (50.6%) |

7,976 (20.7%) |

155,480 (25.2%) |

|

Total |

457,745 (40.2%) |

176,791 (38.4%) |

237,775 (42.8%) |

63,899 (22.2%) |

936,210 (38.3%) |

|

aTotal numbers do not include the Coast Guard. bIn contrast with the Army and Air Force, the Navy and Marine Corps do not have a National Guard component. SOURCE: DOD, 2007. |

|||||

FIGURE 2.1 (A) Age of children (active component); (B) Age of children (reserve component).

SOURCE: DOD, 2007.

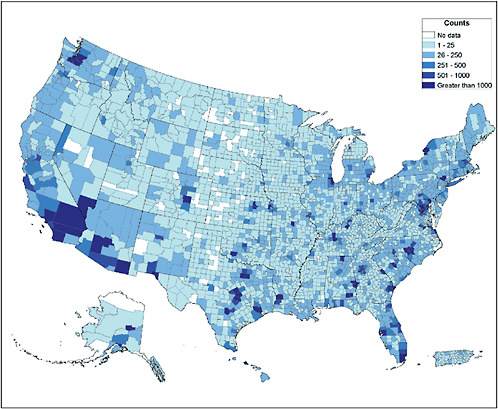

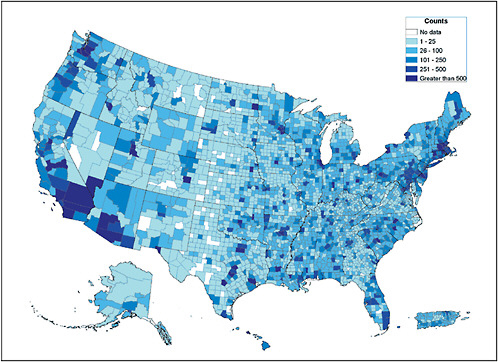

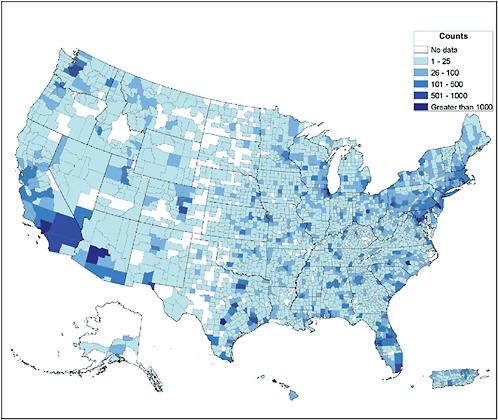

Over 1.1 million active-component members are stationed in the United States. Of them, 54.5% are in six states: California (12.9%), Virginia (11.4%), Texas (10.7%), North Carolina (8.4%), Georgia (6.0%), and Florida (5.1%) (DOD, 2007). Figure 2.2 illustrates the geographic distribution of states to which Army personnel return after deployment to OEF or OIF. The 10 states where the greatest number of reserve-component members reside are California (6.9%), Texas (6.4%), Florida (4.3%), Pennsylvania (4.2%), New York (3.6%), Georgia (3.5%), Ohio (3.4%), Alabama (3.1%), Illinois (3.1%), and Virginia (3.0%) (DOD, 2007). Figures 2.3 and 2.4 show the geographic distribution in the Army National Guard and Army Reserve, respectively.

FIGURE 2.4 Counties of residence of deployed OEF and OIF Army reserve military personnel.

SOURCE: Defense Manpower Data Center, 2009a.

OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM AND OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM: UNIQUE CHARACTERISTICS

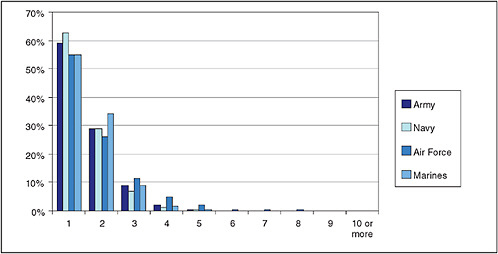

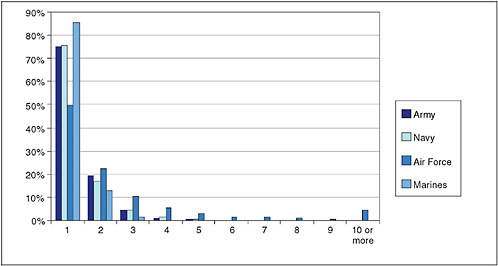

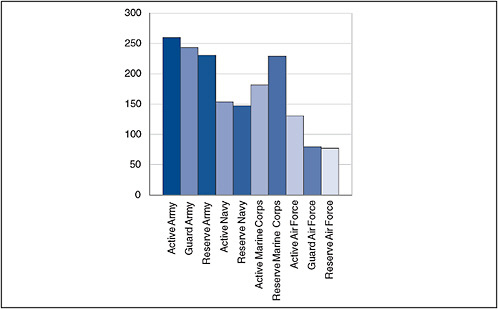

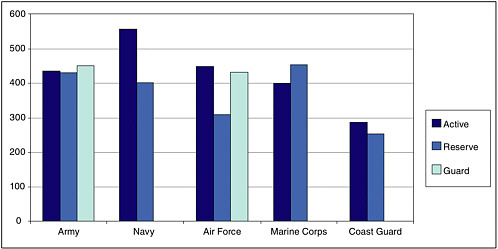

In addition to differences from previous wars in the demographic composition of the current all-volunteer force, deployment to OEF and OIF has some unique characteristics. Because the number of troops in the active component of the military is smaller than in past conflicts, DOD has had to send military personnel on repeat tours in theater to meet the demands of an extended conflict. Overall, about 40% of current military service members have been deployed more than once (Defense Manpower Data Center, 2009b); 263,150 service members have served more than two tours. Figure 2.5 illustrates the number of tours of duty to OEF or OIF of active-component members by branch of military service, and Figure 2.6 shows the number of tours of reservists. The repeat deployments have created more frequent transitions for the service members and their families to navigate, which in turn can create additional stress and

possible gaps in care—the stresses may not be the same for all service members, and there appear to be differences between members of the active component and members of the reserve component. Moreover, pressure on troops needed for deployment has resulted in some combat units spending longer tours and shorter periods at home between tours (referred to as dwell time) than the benchmark set by DOD (CBO, 2005). The stated policy for the active component units is 2 years of dwell time; as of August 1, 2008, service members were not to be deployed for more than 12 months (Davis et al., 2005). For the reserve component, the policy is 1 year deployed and 5 years at home (Davis et al., 2005). Figures 2.7 and 2.8 show the average time deployed and the average dwell time by branch for both components, respectively. The average dwell times are substantially shorter than the established policies. According to a 2007 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, the demands of the conflicts have made implementation of the “new” policy difficult (GAO, 2007).

Another substantial difference in how troops are being used to fight in Iraq and Afghanistan compared with past conflicts has been the growing reliance on the National Guard and reserves (Table 2.1). Since the early 1990s, with the end of the Cold War, there has been a steady reduction in the total number of troops in the US military.2 Although the decline was halted briefly at the time of Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm, thereafter the US military continued to reduce its active and reserve forces.3 Despite the drawdown of military forces, the number of operational deployments increased for frequent peacekeeping missions and humanitarian operations (Jacobs, 2000). For example, the Army National Guard’s combat brigades have been deployed since January 2003 at a rotation ratio4 of 4.3, which is higher than the stated goal of seven Army National Guard units at their home stations for every one deployed (CBO, 2007b). Furthermore, the Army National Guard has long had more personnel slots in its structure than it has been able to fill, and this has led to understaffed units. The pre-existing personnel shortage has been exacerbated by OEF and OIF. When a unit is mobilized and deployed, it must be brought up to at least 100% of its authorized strength; this is accomplished by transferring personnel from other, “donor” units.5 The resulting undermanning of donor units is exacerbated when donor units themselves are deployed (CBO, 2007b).

FIGURE 2.7 Average time deployed in days by branch of military subdivided by active component and reserve component.

SOURCE: Defense Manpower Data Center, 2009b.

FIGURE 2.8 Average dwell time in days by branch of military subdivided by active component and reserve component.

SOURCE: Defense Manpower Data Center, 2009b.

CURRENT IMPACT ON OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM AND OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM SERVICE MEMBERS

Throughout history, service members have faced challenges in readjusting to civilian life. Obstacles in navigating the range of available DOD and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) benefit programs have been consistently reported in connection with each conflict since World War I. In addition, each generation of soldiers has faced challenges specific to its experiences in readjusting to civilian society. The features noted in the previous section—the shift in demographics, the smaller active-duty all-volunteer force, the greater reliance on the reserve component, and the repeated and extended deployments—have also led to issues that did not have to be addressed in previous conflicts. For example, greater reliance on older, married soldiers creates a new array of concerns related to family-life readjustment and the well-being of older children. Repeat deployments can also lead to additional financial and employment-related burdens, although for personnel with skills in great demand special pay and allowances may provide additional compensation beyond the combat- and deployment-related pay (such as imminent-danger pay, hardship-duty pay, and family-separation allowances) (CBO, 2007a). The direct effect of deployment on the service members and their families is not known, but this section briefly summarizes some of the challenges related to readjusting after deployment that have been reported in the popular press, government reports, and the peer-reviewed literature. The issues are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Overview of Health Outcomes

The proportion of service members who have been killed or wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan has been lower than that in past conflicts. As of November 24, 2009, 5,2866 US troops had died and 36,0217 had been wounded (DOD, 2009). Fatality-to-wounded ratios have been 1:5.0 for OEF and 1:7.2 for OIF (DOD, 2009) compared with 1:2.6 in Vietnam and 1:1.7 in World War II (Leland and Oboroceanu, 2009). The lower number of fatalities is attributable to the improved body armor provided to service members and improved emergency medical care in the war zone (such as rapid evacuation to a trauma center). Consequently, more service members survive to return home with severe combat-related injuries that require additional care. For example, a large number of military personnel have survived blasts that resulted in such injuries as hearing loss and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Myles, 2008). An estimated 10–20% of OEF and OIF Army and Marine Corps service members have sustained mild TBI that has been associated with various long-term health outcomes (IOM, 2009b). According to a study by Hoge et al. of 303,905 soldiers and marines, 19.1% of troops returning from Iraq and 11.3% of those returning from Afghanistan reported mental health problems compared with 8.5% of those returning from deployments elsewhere (Hoge et al., 2006).

Repeated deployments themselves have also contributed to mental health issues. About 27% of those who have been deployed three or four times have received diagnoses of depression, anxiety, or acute stress compared with 12% of those deployed once (MHAT-V, 2008).

Another troubling consequence of OEF and OIF deployment is the increase in the number of suicides reported in soldiers serving in Iraq and Afghanistan since the start of the conflicts. Historically, the suicide rate has been lower in military members than in civilians matched by age and sex. In 2003, the suicide rate in the US military was estimated at 10–13 per 100,000 troops, depending on the branch of the military (Allen et al., 2005), compared with 13.5 per 100,000 civilians 20–44 years old and 20.6 per 100,000 civilian men 20–34 years old, the demographic that covers most US soldiers in Iraq (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). However, recent data from the National Violent Death Reporting System indicate that male veterans8 18–29 years old had a suicide rate of 45.0 per 100,000 in 2005 compared with 20.4 in males in that age group in the general population. As of October 2009, there were already 133 reported suicides (90 confirmed and 43 pending), which is the record for a year; in the same period in 2008, there were 115 confirmed suicides of active-duty soldiers (Department of the Army, 2009); hence, 2009 might well see a new record. A new National Institute of Mental Health–sponsored study of suicide in the US armed forces has been started to investigate the risk factors for soldier suicide.

Problems with substance abuse, particularly alcohol, have also been reported in OEF and OIF military personnel and veterans in the peer-reviewed literature and in the popular press. It is unknown whether the alcohol problems differ between the military population and the civilian population. In the United States, about 1 in 12 adults abuses alcohol or is dependent on alcohol; alcohol problems are highest among people 18–29 years old (NIAAH, 2007). On the basis of data from the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, between 1991–1992 and 2001–2002, alcohol abuse9 increased in the US civilian population from 3.03% to 4.65% while the rate of alcohol dependence10 declined from 4.38% to 3.81% (Grant et al., 2004).

A recent study found that 43% of active-component service members reported binge drinking within the preceding month (Stahre et al., 2009). Moreover, on the basis of mass-media reports, diagnoses of alcoholism and alcohol abuse increased from 6.1 per 1,000 soldiers in 2003 to an estimated 11.4 as of March 31, 2009. Another emerging substance-abuse issue is that many of today’s military personnel are more likely to be addicted to prescription medications, such as opiates for pain control (Curley, 2009). However, because of the long-standing policy whereby self-referral for substance abuse can be reported to the chain of command, the numbers being reported are probably underestimates of the true number. The readjustment needs associated with these health outcomes are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Overview of Social Outcomes

Employment, Financial Hardships, and Homelessness

Several non-health-related problems faced by service members have been documented. Gaps in pay and benefits that have resulted in debt and other hardships have been reported. For example, there is evidence that service members have been pursued for repayment of military

debt, such as unpaid expenses for lost or damaged military equipment, medical services, household moves, insurance premiums, and travel advances. Often times, however, they were pursued for collection of military debts that were incurred through no fault of their own; those included overpayment of pay and allowances, pay calculation errors, and erroneous leave payments (GAO, 2006). The service members have also been prevented from obtaining loans (GAO, 2005). Moreover, there have been reports in the popular press that National Guard and reserve members have been unable to return to the civilian jobs that they left before their deployments (60 Minutes, November 2, 2008) despite protective provisions in the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994, a federal law intended to ensure that persons who serve or have served are not disadvantaged in their civilian careers because of their service. According to the Pentagon, over 10% of the National Guard and reserve members report such employment-related problems (60 Minutes, November 2, 2008). The problem is especially common among those employed by small businesses: Veterans for America found that some small businesses avoid hiring citizen soldiers (Veterans for America, 2008). Almost 20% of recent veterans are unemployed, and 25% of those who are employed earn less than $21,000 per year (Myles, 2008).

According to the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans (2009), veterans are more likely to become homeless because their work skills may not be readily transferable to the civilian sector. In addition, although there are no data on the number of homeless OEF and OIF veterans, because of the large number of troops returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with mental health problems or TBI, there is concern that they may be at higher risk for homelessness.

Women

Women have made up a greater percentage of the military force during OIF and OEF than in previous conflicts. Because in most families mothers have primary responsibility for arranging for and providing care for children, large-scale deployments have raised concerns about the effects of mothers’ deployments on their children and about the possible strains on families if both partners must maintain careers to preserve their living standards (McFarlane, 2009). A recent study by Vogt et al. (2008) found that active-component women were more susceptible to stressors of deployment than women in the reserve component. The study also found that the longer a parent is absent, the greater the risk of family dysfunction after deployment, and the risk is greater when the deployed parent is the mother.

Family Relationships

Deployments and frequent relocation are inherent in military life. The physical separation, especially when the deployments are to combat zones, is difficult for families. Often, families have little warning of a deployment, and the deployments extend beyond the originally stated duration. Adjusting to the different roles that each partner plays before and after deployment (for example, going from an interdependent state to an independent state and back to an interdependent state) is one of the challenges that married couples face. Service members are expected to work long and unpredictable hours, especially in preparation for deployment, and this puts additional stresses on couples and families. Moreover, when service members return from deployment with physical injuries or cognitive deficits, these problems may contribute to marital conflict. Although those effects have not been studied extensively in the military population, data on marital satisfaction in civilian populations suggest that depression,

posttraumatic stress disorder, and TBI all adversely affect personal relationships and pose a higher risk of divorce (Davila et al., 2003; Kessler et al., 1998; Kravetz et al., 1995; Kulka et al., 1990). Recent data from the Army show an overall increase in the number of divorces since the start of OEF and OIF, especially in female soldiers. Cotton (2009) reported that in 2008, 8.5% of marriages ended in divorce in women compared with 5.7% in 2000. Similarly, although the rate is lower, 2.9% of men reported marriages ending in divorce in 2008 compared with 2.2% in 2000.

The rate of domestic violence is higher in military couples than in civilian couples. Marshall et al. (2005) reported that wives of Army servicemen reported significantly higher rates of husband-to-wife violence than demographically matched civilian wives. Although it has been reported that spousal abuse has declined over the last few years, domestic violence still affects 20% of military couples in which the service member has been deployed for at least 6 months (Booth et al., 2007).

Children

The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have taken a toll on the children of US troops deployed there. Children of US troops deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan reportedly sought outpatient mental health services 2 million times in 2008 (Andrews et al., 2008). Inpatient visits by military children have increased by 50% since 2003. Additionally, an increase in the rate of child maltreatment has been reported since the start of the conflicts. Rentz et al. (2007) conducted a time-series analysis from 2000 to 2003 to investigate the effect of deployment on the occurrence of child maltreatment in military and nonmilitary families. They reported a statistically significant two-fold increase in substantiated maltreatment in military families in the 1-year period after September 11, 2001, compared with the period before then. A recent study of over 1,700 military families (Gibbs et al., 2007) found that the overall rate of child maltreatment, especially child neglect, was higher when the soldier-parents were deployed than when they were not deployed. Because of the demographics of those who are serving in Iraq and Afghanistan (older service members who are married and have children), the number of children who have been affected by these conflicts is clearly larger than in past conflicts.

Caregivers

Many severely injured service members depend on family members for daily caregiving. The findings of the President’s Commission on Care for America’s Returning Wounded Warriors (in what has been known as the Dole–Shalala report) reported in 2007 that in a random sample of 1,730 OEF and OIF veterans, 21% of active-component, 15% of reserve-component, and 24% of retired service members had a family member or friend who had been forced to leave a job to care for an OIF or OEF veteran full-time (President’s Commission on Care for America’s Returning Wounded Warriors, 2007). In addition, 33% of active-component, 22% of reserve-component, and 37% of retired service members reported that a family member or friend relocated temporarily to spend time with a wounded service member while he or she was in the hospital.

OVERVIEW OF FEDERAL READJUSTMENT RESOURCES

US troops who serve are entitled to benefits, such as health care. Health care is delivered by DOD through the military health system (MHS) to active-component service members and their dependents, to reserve-component members and their dependents when they are on active duty, and to some military retirees and their dependents. The MHS delivers care through 59 hospitals and over 400 clinics (TRICARE, 2009). The system is supplemented through TRICARE (formerly known as the Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services), which provides civilian health benefits for military personnel, military retirees, and their dependents. However, TRICARE services are time-limited after separation.11 Moreover, health-care providers who accept TRICARE may be harder to find in nonmilitary communities where some reserve-component service members and their families live (IOM, 2010; Kudler and Straits-Tröster, 2009) than near military installations.

Service members who separate from the military may be eligible for health care administered by VA, which is organized into 23 veterans-integrated service networks where veterans who qualify (Table 2.5) can get free health care. All veterans with at least 24 months of continuous active-duty service and other than a dishonorable discharge are eligible to receive care from VA. OEF and OIF veterans have 5 years after their military separation to enroll in VA health-care services. Enrollment eligibility is determined through an eight-step process (see Chapter 5) in which the veteran12 completes and submits the Application for Health Benefits (VA Form 10-10EZ). In 7–10 days, a decision letter is sent to the veteran stating his or her enrollment eligibility (Task Force on Returning Global War on Terror Heroes, 2007). Effective January 28, 2003, OEF and OIF veterans who enroll within the first 5 years after separating from the military are eligible for enhanced enrollment placement into priority group 6 for 5 years after discharge. VA provides other benefits to veterans, including home loans, life insurance, vocational counseling, employment assistance, and education and training.

TABLE 2.5 Health-Care Priority Groups

|

Priority Group |

Description |

|

1 |

Veterans with service-connected disabilities (SCDs) rated 50% or more disabling |

|

2 |

Veterans with SCDs rated 30% or 40% disabling |

|

3 |

Veterans who are former prisoners of war, were awarded the Purple Heart, were discharged for an SCD, have SCDs rated 10% or 20% disabling, or were disabled by treatment or vocational rehabilitation |

|

4 |

Veterans who are receiving aid and attendance benefits or are housebound and veterans who have been determined by the VA to be catastrophically disabled |

|

5 |

Veterans without SCDs or with noncompensable SCDs rated 0% disabling who are living below established VA means-test thresholds, veterans who are receiving VA pension benefits, and veterans who are eligible for Medicaid benefits |

|

6 |

Veterans of either World War I or the Mexican Border War; veterans seeking care solely for disorders |

|

Priority Group |

Description |

|

|

associated with exposure to chemical, nuclear, or biologic agents in the line of duty (including Agent Orange, atmospheric testing, and Project 112/Shipboard Hazard and Defense); and veterans with compensable SCDs rated 0% disabling |

|

7 |

Veterans with net worth above the VA means-test threshold and below a geographic index defined by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) |

|

8 |

Veterans with net worth above both the VA means-test threshold and the HUD geographic index |

|

SOURCE: IOM, 2009a. Adapted from VA, 2008. |

|

In addition to the DOD and VA health care available to returning OEF and OIF veterans, numerous informal services are provided by veterans’ service organizations and charities that are funded through federal sources, state programs, and private foundations. Some organizations, such as the Wounded Warrior Project, provide employment support that helps to match returning OEF and OIF veterans with job opportunities. Others, such as Grace After Fire, provide on-line recovery services to female veterans. Because of the great breadth and number of initiatives that are available at the grassroots level, it is beyond the scope of this report to provide a comprehensive review of them; however, Chapter 5 provides more detail on the available federal programs that have been developed in response to OEF and OIF.

CONCLUSION

The current conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq pose unique challenges to DOD and VA. Even as they continue to address the readjustment needs of OEF and OIF service members, veterans, and their families, more work remains. The demands on the forces, the repeated deployments, the shorter dwell times, the activation of parents, and the separation of families have all resulted in unmet needs for many of those who serve. The following chapters provide more detailed information on what those needs are, what programs are available, and what the possible next steps to address the needs might be.

REFERENCES

60 Minutes. 2008. Reservists Rocky Return to Job Market. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/10/30/60minutes/main4558315.shtml?tag=contentMain;contentBody (accessed March 18, 2010).

Allen, J. P., G. Cross, and J. Swanner. 2005. Suicide in the Army: A review of current information. Military Medicine 170(7):580-584.

Andrews, K., K. Bencio, J. Brown, L. Conwell, C. Fahlman, and E. Schone. 2008. Health Care Survey of DOD Beneficiaries 2008 Annual Report. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. 2009. Background Information on Deployments to OEF/OIF, June 11, 2009.

Booth, B., M. W. Segal, and D. B. Bell. 2007. What We Know about Army Families: 2007 Update. Department of the Army, Family and Morale, Welfare and Recreation Command. Accessed online: http://www.army.mil/fmwrc/documents/research/whatweknow2007.pdf (July 17, 2009).

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2005. The Effects of Reserve Call-Ups on Civilian Employers. Washington, DC: The Congress of the United States, Congressional Budget Office. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/63xx/doc6351/05-11-Reserves.pdf (accessed June 18, 2009).

CBO. 2007a. A CBO Study: Evaluating Military Compensation. http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA469762&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf (accessed November 24, 2009).

CBO. 2007b. CBO Testimony: Statement of J. Michael Gilmore, Assistant Director for National Security, on Issues That Affect the Readiness of the Army National Guard and Army Reserve before the Commission on the National Guard and Reserves, May 16, 2007.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html (accessed August 26, 2009).

Cotton, R. D. 2009. Clear, Hold and Build: Strengthening Marriages to Preserve the Force. Carlisle Barracks, PA: US Army War College. http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA498102&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf (accessed July 31, 2009).

Curley, B. 2009. Wounds of War: Drug Problems Among Iraq, Afghan Vets Could Dwarf Vietnam. The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. http://www.jointogether.org/news/features/2009/wounds-of-war-drug-problems.html (accessed October 28, 2009).

Davila, J. B., R. Karney, T. W. Hall, T. N. Bradbury. 2003. Depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction: Within-subject associations and the moderating effects of gender and neuroticism. Journal of Family Psychology 17(4):557-570.

Davis, L. E., J. M. Polich, W. M. Hix, M. D. Greenberg, S. D. Brady, and R. E. Sortor. 2005. Stretched Thin: Army Forces for Sustained Operations. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/2005/RAND_MG362.sum.pdf (accessed October 28, 2009).

Defense Manpower Data Center. 2009a. Distribution of Residence Zip Code, June 29, 2009.

Defense Manpower Data Center. 2009b. Profile of Service Members Ever Deployed, June 29, 2009.

Department of the Army. 2009. Army Releases October Suicide Data. http://www.army.mil/-newsreleases/2009/11/13/30396-army-releases-october-suicide-data/?ref=news-releases-title1 (accessed November 30, 2009).

DOD (Department of Defense). 2007. Demographics 2007: Profile of the Military Community. Washington, DC: Department of Defense.

DOD. 2009. Defenselink Casualty Update. http://www.defenselink.mil/news/casualty.pdf (accessed November 24, 2009).

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2005. More DOD Actions Needed to Address Servicemembers’ Personal Financial Management Issues. Washington, DC: GAO. GAO-05-348.

GAO. 2006. Military Pay: Hundreds of Battle-Injured GWOT Soldiers Have Struggled to Resolve Military Debts. Washington, DC: GAO.

GAO. 2007. Military Personnel: DOD Lacks Reliable Personnel Tempo Data and Needs Quality Controls to Improve Data Accuracy. Washington, DC. GAO-07-780. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d07780.pdf (accessed July 21, 2009).

Gibbs, D. A., S. L. Martin, L. L. Kupper, and R. E. Johnson. 2007. Child maltreatment in enlisted soldiers’ families during combat-related deployments. JAMA 298(5):528-535.

Grant, B. F., D. A. Dawson, F. S. Stinson, S. P. Chou, M. C. Dufour, and R. P. Pickering. 1994. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 74(3):223-234.

Hoge, C. W., J. L. Auchterlonie, and C. S. Milliken. 2006. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 295(9):1023-1032.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009a. Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2009b. Gulf War and Health Volume 7: Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2010. Provision of Mental Health Counseling Services Under TRICARE. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jacobs, T. O. 2000. American Military Culture in the Twenty-First Century: A Report of the CSIS International Security Program. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Jensen, J. A. 2002. The Effect of Operational Deployments on Army Reserve Component Attrition Rates and Its Strategic Implications. http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA403763&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf (accessed August 18, 2009).

Kessler, R. C., E. E. Walters, and M. S. Forthofer. 1998. The social consequences of psychiatric disorders, III: Probability of marital stability. American Journal of Psychiatry 155(8):1092-1096.

Kravetz, S., Y. Gross, B. Weiler, M. Ben-Yakar, M. Tadir, M. J. Stern. 1995. Self-concept, marital vulnerability and brain damage. Brain Injury 9(2):131-139.

Kudler, H., and K. Straits-Tröster. 2009. Partnering in support of war zone veterans and their families. Psychiatric Annals 39(2):64-70.

Kulka, R., W. Schlenger, J. Fairbank, R. Hough, B. Jordan, C. Marmar, and D. Weiss. 1990. Trauma and the Vietnam Generation: Report of Findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Leland, A., and M.-J. Oboroceanu. 2009. American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics, Updated September 15, 2009. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RL32492.pdf (accessed November 24, 2009).

Marshall, A. D., J. Panuzio, and C. T. Taft. 2005. Intimate partner violence among military veterans and active duty servicemen. Clinical Psychology Review 25(7):862-876.

McFarlane, A. C. 2009. Military deployment: The impact on children and family adjustment and the need for care. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 22(4):369-373.

MHAT-V (Mental Health Advisory Team). 2008. Report of the Mental Health Advisory Team (MHAT) V.

Myles, C. 2008. From Combat to Classroom: Transitions of Modern Warriors, Presentation by an OEF/OIF Outreach Coordinator at the Wm S. Middleton Memorial Veterans’ Hospital, Madison, WI. Paper presented at Wisconsin Association on Higher Education and Disability, Madison, WI.

National Coalition for Homeless Veterans. 2009. Statement of the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans before the US Senate Committee on Veterans Affairs Subcommittee on Economic Opportunity, March 4, 2009. http://www.nchv.org/content.cfm?id=78 (accessed August 3, 2009).

NIAAA (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism). 2007. FAQs for the General Public. http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/FAQs/General-English/default.htm#whatis (accessed December 7, 2009).

Panangala, S. V. 2007. Veterans Health Care Issues. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

President’s Commission on Care for America’s Returning Wounded Warriors. 2007. Serve, Support, Simplify: Report of the President’s Commission on Care for America’s Returning Wounded Warriors. Washington, DC.

Rentz, E. D., S. W. Marshall, D. Loomis, C. Casteel, S. L. Martin, and D. A. Gibbs. 2007. Effect of deployment on the occurrence of child maltreatment in military and nonmilitary families. American Journal of Epidemiology 165(10):1199-1206.

Stahre, M. A., R. D. Brewer, V. P. Fonseca, and T. S. Naimi. 2009. Binge drinking among US active-duty military personnel. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36(3):208-217.

Summers, H. G. 1985. The Vietnam War Almanac. New York: Facts on File Publications.

Tanielian, T., and L. H. Jaycox. 2008. Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Arlington, VA: RAND Corporation.

Task Force on Returning Global War on Terror Heroes. 2007. Task Force Report to the President: Returning Global War on Terror Heroes. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs. http://www1.va.gov/taskforce/ (accessed July 9, 2009).

TRICARE. 2009. What is TRICARE? http://www.tricare.mil/mybenefit/home/overview/WhatIsTRICARE (accessed December 1, 2009).

US Census Bureau. 2000. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin. http://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/c2kbr01-1.pdf (accessed August 25, 2009).

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2008. VA Health Care Eligibility and Enrollment. http://www.va.gov/healtheligibility/eligibility/PriorityGroupsAll.asp (accessed April 3, 2009).

Veterans for America. 2008. The Alaska Army National Guard: A “Tremendous Shortfall.” Veterans for America: Washington, DC.

Vogt, D. S., R. E. Samper, D. W. King, L. A. King, and J. A. Martin. 2008. Deployment stressors and posttraumatic stress symptomatology: Comparing active duty and National Guard/Reserve personnel from Gulf War I. Journal of Traumatic Stress 21(1):66-74.