Summary

From the days of biplanes and open cockpits, the air forces of the United States have relied on the mastery of technology to ensure what, in 1921, Giulio Douhet called “the command of the air.”1 And while the weapons of air warfare have changed, the vital importance of technological superiority to the United States Air Force has not.

Although evidence exists—for example, Government Accountability Office (GAO)2 reports, failed programs, and programmatic breaches in cost, schedule, and technical performance—that the Air Force is currently struggling to incorporate technology in its major systems acquisitions successfully, it is important to note that the path toward technological supremacy has never been a smooth one.3,4,5 Describing the technological travails that he faced 75 years ago while building the

early Army Air Corps, General of the Air Force Henry H. (“Hap”) Arnold told of a reality not unlike that of today:

Planes became obsolescent as they were being built. It sometimes took five years to evolve a new combat airplane, and meanwhile a vacuum could not be afforded…. I also had trouble convincing people of the time it took to get the “bugs” out of all the airplanes. Between the time they were designed and the time they could be flown away from the factory stretched several years. For example … the B-17 was designed in 1934, but it was 1936 before the first test article was delivered. The first production article was not received by the Air Corps until 1939. You can’t build an Air Force overnight.6

Yet the 5 years from design to operation that General Arnold described have now stretched in some cases to 20 years and more, and cost has increased similarly. Much of the delay and cost growth afflicting modern Air Force programs is rooted in the same area that plagued General Arnold: the incorporation of advanced technology into major systems acquisition.

STUDY APPROACH

In response to a request from the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Science, Technology, and Engineering, the National Research Council (NRC) formed the Committee on Evaluation of U.S. Air Force Preacquisition Technology Development.7 The statement of task for this study is as follows:

-

Examine appropriate current or historical DoD [Department of Defense] policies and processes, including the PPBES [Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution System], DoD Instruction 5000.02, the Air Force Acquisition Improvement Plan, JCIDS [Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System], and DoD and Air Force competitive prototyping policies to comprehend their impact on the execution of pre-program of record technology development efforts.

-

Propose any changes to the Air Force workforce, organization, policies, processes and resources, if any, to better perform preacquisition technology development. Specific issues to consider include:

-

Resourcing alternatives for Pre-Milestone B activities

-

The role of technology demonstrations

-

-

Study and report on industry/Government best practices to address both evolutionary (deliberate) and revolutionary (rapid) technology development.

-

Identify potential legislative initiatives, if any, to improve technology development and transition into operational use.

With the task in mind, the committee began a process of evidence gathering in which efforts were focused on gaining a current and accurate picture of the situation in the air, space, and cyberspace domains, through documentary research and through interactions with a large number of government agencies and offices. The committee conducted four data-gathering meetings at which input to the study was provided by the following: senior Air Force leaders, including representatives of several Air Force Major Commands; representatives from the other military departments; senior officials in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD); professional staff members from key congressional oversight committees; and senior industry executives. This effort was followed by an exploration of best practices in which the lessons of technological success stories from academia, government, and industry were studied.

Early in the study, the committee developed a framework, the “Three Rs,” for organizing its findings and recommendations. The framework describes characteristics that, in the committee’s judgment, need to be addressed fully in order for successful technology development to occur. That framework is composed of the following:

-

Requirements—clear, realistic, stable, trade-off tolerant, and universally understood;

-

Resources—adequate and stable, and including robust processes, policies, and budgets; and

-

The Right People—skilled, experienced, and in sufficient numbers, with stable leadership.

On the basis of this framework, the committee developed a number of findings and recommendations that are presented in Chapters 2 through 4; the full set of recommendations is provided below.8 In keeping with its statement of task, the committee studied the current state of Air Force technology development and the environment in which technology is acquired, and then it looked at best practices from both government and industry. Because the resulting recommendations are in all cases within the power of the Air Force to implement, the committee chose

|

8 |

The findings and recommendations retain their original numbering regardless of where they appear in the text: for example, Recommendation 4-1 is the first recommendation in Chapter 4. |

not to specify any near-term legislative initiatives, the possibility of which was envisioned in the statement of task.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Requirements

There is very little new in the management of technology development. Important lessons have been learned before by the Air Force, and, regrettably, many seem to have been forgotten. At the same time, industry has learned—and the Air Force is seemingly having to relearn—that simultaneously developing new technology within an acquisition program is a recipe for disaster. Just as in Hap Arnold’s day, requirements that are unclear, unrealistic, or unstable inhibit successful technology insertion. In 1922, General Arnold studied the biplane pursuit craft that represented the technology of the day, and he came to understand fully the dangers of shifting requirements in an acquisition program:

[O]nce production had begun, the line must be allowed to run undisturbed. Any new improvements should wait until a specified point…. Mass production requires certain sacrifices in technological advancement, [Arnold] reported; the trick was to be aware of what was needed before production began, “and then to stick to it for a certain period even though it can be improved, until such time as the improvement can be incorporated without materially affecting production.”9

Although the dangers posed by shifting requirements are well known, the temptation to improve systems in development can be hard to resist. This temptation only increases as product development cycles lengthen from years to decades.10

RECOMMENDATION 4-1

To ensure that technologies and operational requirements are well matched, the Air Force should create an environment that allows stakeholders—warfighters, laboratories, acquisition centers, and industry—to trade off technologies with operational requirements prior to Milestone B.

RECOMMENDATION 4-2

To enable (1) a more disciplined decision-making process and (2) a forum in

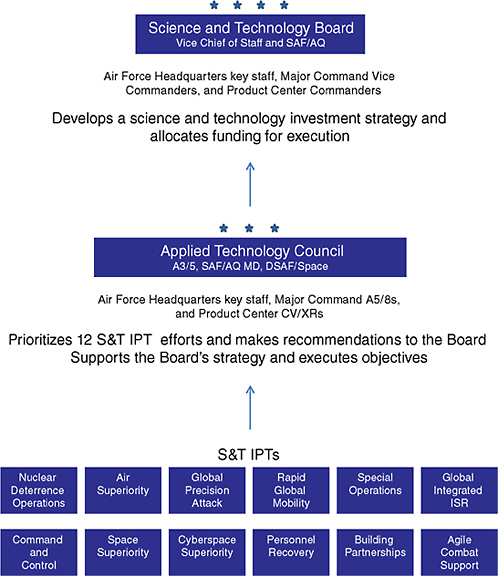

which all stakeholders—those from the science and technology (S&T), acquisition, and warfighting Major Command (MAJCOM) communities—can focus their attention jointly on critical technology development questions and then make tough strategy and resource calls efficiently at a level where the decisions are most likely to stick, the Air Force should consider adopting a structure similar to the Navy’s S&T Corporate Board and Technology Oversight Group and the Army Technology Objectives Process and Army S&T Advisory Group. A committee-developed notional organization for Air Force consideration (Figure S-1) addresses this potential and is tailored to Air Force missions and organization. In addition, the Air Force should consider allocating funding for technology development, including funding for 6.4, or advanced component development and prototypes, to the Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) and Air Force Space Command (AFSPC), unless precluded by law from doing so.

In the opinion of the committee, this recommendation to add another organization to the Headquarters Air Force does not diminish the statutory and mission responsibilities of the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Acquisition) (SAF/AQ)11 and is justified by the seriousness of the need. In the committee’s judgment, no other approach would meet the need to bring together the S&T, acquisition, and warfighting MAJCOM communities at a level that could make the difficult decisions. The fundamental premise of Recommendation 4-2 is the importance of technology to the Air Force, as described in the introductory paragraphs of Chapter 1 and reiterated in introductory statements in Chapter 2. Findings 2-8 and 2-9 (first presented in Chapter 2 and then repeated in the context of the associated recommendation in Chapter 4) identify significant shortfalls in decision making for Air Force technology development and transition—that is, the lack of a process for technology transition and, at a higher level, the lack of a service-wide unifying S&T strategy to guide investments—which, in the judgment of the committee, need to be addressed. The structure proposed in Recommendation 4-2 would give SAF/AQ greater leverage to ensure that the right technology is being developed, matured, and transitioned. Furthermore, the cross-domain character of technology development, addressed in Chapters 1 through 3 of this report, presents challenges that the recommended S&T Board could address efficiently with a diverse set of stakeholders at the table. Finally, given the ever-increasing complexity and budget implications of new weapon systems, in the opinion of the committee the status quo is not acceptable.

Resources

None of the many Air Force presenters who briefed the committee was able to articulate an Air Force-level, integrated S&T strategy, nor could any identify a single office with authority, resources, and responsibility for all S&T initiatives across the Air Force. Instead, there appears to be an assortment of technology “sandboxes,” in which various players work to maximize their organizational self-interest, as they perceive it. In such a system, optimization will always take place at the subunit level, with less regard for the health of the overarching organization.

Processes and procedures to facilitate the successful integration of technology into major system acquisitions were developed by the Air Force long ago, and some were in existence within relatively recent memory. But for various reasons, many of these were ended or allowed to atrophy. Chief among these were initiatives such as the historical Air Force Systems Command’s Vanguard process and the acquisition Product Centers’ Development Planning Organizations (XRs), which for decades formed a crucial link between warfighter requirements on the one hand and laboratory and industry capabilities on the other. Funding for Development Planning was zeroed out a decade ago, and the negative impacts of that decision are now clear. Other such activities, like systems engineering and Applied Technology Councils, also declined in importance in some arenas, with similar harmful results.

Other processes that do exist elsewhere need to be adopted more accurately, effectively, and consistently by the Air Force.12 For example, Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) are a process created by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in which technology is incorporated in operational environments only after it is proven to be mature. The committee observed many examples from industry, NASA, and the AFSPC in which disciplined and objective adherence to rigorous technology readiness principles led to the successful incorporation of new technology into major systems. The Air Force as a whole, however, has yet to demonstrate full commitment to TRL principles.

RECOMMENDATION 4-3

Since DoD Instruction 5000.02 incorporates increased pre-Milestone B work, the Air Force should bring Pre-Milestone B work content back into balance with available resources by some combination of (1) DoD Instruction 5000.02 tailoring and/or (2) additional expertise, schedule, and financial resources. Examples of expanded content include competitive prototyping, demonstrating

|

12 |

DoD. 2010. Quadrennial Defense Review Report. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense. Available at http://www.defense.gov/qdr/images/QDR_as_of_12Feb10_1000.pdf. Accessed August 12, 2010. |

technology in operationally relevant environments, and completing preliminary design prior to Milestone B.

RECOMMENDATION 4-4

Knowledgeable, experienced, and independent technical acquisition professionals outside the program office should conduct technology, manufacturing, and integration assessments using consistent, rigorous, and analytically based standards. While the Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-23) requires this effort to be executed at the OSD level, this organic capability needs to be developed and assigned to the AFMC and the AFSPC. Once this capability has been effectively demonstrated by the Air Force, legislative relief should be sought.

RECOMMENDATION 4-5

To increase the likelihood of acquisition success, the Air Force should enter Engineering and Manufacturing Development (Milestone B) only with mature technologies—that is, with technologies at TRL 6 or greater.

RECOMMENDATION 4-6

The Air Force should drive greater collaboration between warfighters (to include joint and coalition partners), laboratories, developers, and industry. One approach is to establish collaboration forums similar to the Ground Robotics Consortium and the Army Armament Research, Development, and Engineering Center’s National Small Arms Center.

The Right People

The literal decimation of the Air Force acquisition workforce over the past two decades is well known. Although a workforce can be slashed in a very short time, rebuilding it in terms of knowledge, skills, and experience can take decades. The Air Force seems to have recognized the damage done in this regard and is moving to reverse course, with substantial hiring of acquisition specialists at both the trainee and the journeyman level.

Importantly, the present study is focused not on acquisition broadly, but rather on the specific intersection between technology and major systems acquisition. With this in mind, the recommendation in the area of the “Third R” is focused on continuing the reinvigoration of Development Planning. The Air Force has recognized the tremendous cost imposed by the elimination of the XRs, and it has moved to begin to recoup its losses by restoring funding and people to the vital Development Planning function. This is a good start, but as with rebuilding the general acquisition force, more needs to be done, and progress will occur slowly.

RECOMMENDATION 4-7

The Air Force should accelerate the re-establishment of the Development Planning organizations and workforce and should endow them with sufficient funds, expertise, and authority to restore trust in their ability to lead and manage the technology transition mission successfully.

A FINAL COMMENT: “THE DEATH SPIRAL,” AND THE CASE OF THE 137-PERSON REVIEW TEAM

Over the months of this study, the committee found substantial evidence of a condition that, although perhaps beyond the strict limits of the statement of task, was tightly interwoven with the issues of technology and major systems acquisition. That condition is the pervasive lack of trust apparent in the entire DoD systems acquisition process. This lack of trust is both cause and effect, in some ways being created by ineffective technology insertion and in other ways creating its own inefficiencies throughout the process.

Exactly where the Death Spiral began is open to debate, a chicken-or-egg type of argument. Did technological failure and acquisition disappointments create the massive growth of oversight at every level, which slows the acquisition process and saps its energy? Or is it equally plausible that the growth of oversight in fact creates the very failures in cost, schedule, and performance that it is designed to prevent?

What is certain is that an unhealthy and self-perpetuating spiral involving the loss of trust and the growth of oversight does in fact exist. One presenter to the committee spoke of a program to which the contractor had assigned 80 engineers, who stood stunned as a government review team arrived with 137 participants, most of them junior military and civilian employees.13 As was described in the 2008 NRC report Pre-Milestone A and Early-Phase Systems Engineering: A Retrospective Review and Benefits for Future Air Force Systems Acquisition:

The DoD management model is based on a lack of trust. Quantity of oversight has replaced quality. There is no clear line of responsibility, authority, or accountability. Oversight is preferred to accountability…. The complexity of the acquisition process increases cost and draws out the schedule.14

The interaction of technology and acquisition management described in the remainder of this report is a complex subject, and as such it is resistant to easy fixes. Nevertheless, beginning in some way to rebuild the sense of trust that was once present among the participants in these processes would seem a logical place to begin.