2

The Current State of the Air Force’s Acquisition Policies, Processes, and Workforce

From its founding, the United States Air Force (USAF) was based on the premise that gaining and maintaining technological supremacy were essential to its combat success. This technological superiority provided great benefit for both the Air Force and the nation. Comparing its current efforts to its past achievements and successes, the Air Force today finds itself struggling to successfully field new technology in its weapons systems on schedule and within budget. According to a recent independent assessment:

[T]he AF has experienced a number of symptoms that indicate problems with its acquisition system and processes [that bring new technology into operational use]. Some of the most pressing of these symptoms have been: (a) numerous cost-schedule-performance issues; (b) numerous Nunn-McCurdy unit cost breaches; (c) increased time to bring major systems to the field; and (d) successful protests by contractors on major programs.1

This chapter identifies key issues that affect the ability of the Air Force to specify, develop, test, and insert new technology into its major new systems.

CURRENT AND HISTORICAL POLICIES AND PROCESSES RELATED TO TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT

The statement of task for this study required the committee to “examine appropriate current or historical Department of Defense (DoD) policies and processes,

including the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution System, DoD Instruction 5000.02, the Air Force Acquisition Improvement Plan, the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System, and DoD and Air Force competitive prototyping policies to comprehend their impact on the execution of pre-program of record technology development efforts” (for the full statement of task, see Box 1-1 in Chapter 1). The descriptions in the following subsections summarize the above policies and processes. Table 2-1 lists the current policies and processes, as well as their unintended consequences or shortfalls. A more comprehensive discussion of these policies and processes is provided in Appendix C.

Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution System

In the planning phase of the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution System (PPBES), the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and the Joint Staff collaboratively articulate national defense policies and military strategy in the Strategic Planning Guidance (SPG).2 The result is a set of budget-conscious priorities for program development (military force modernization, readiness, and sustainability; and supporting business processes and infrastructure), which is promulgated in the Joint Programming Guidance (JPG).

The next phase of the PPBES, programming, begins with the writing of the Air Force Program Objective Memorandum (POM). The POM balances program budgets as set down in the JPG. The third phase, budgeting, happens concurrently with the programming phase. Each DoD department and agency submits its budget estimate with its POM. The DoD departments and agencies then convert their program budgets into the congressional appropriation structure format and submit them, along with justification. The budget forecasts only the next 2 years, but with more detail than the POM. Execution is the responsibility of the individual services. The Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) process is a very high level strategic process, and as such it addresses preacquisition technology development only indirectly.3

Department of Defense Instruction 5000.02

Although DoD Instruction 5000.02 discusses the preacquisition phase, it provides little “how-to” guidance, nor does it provide any formal direction regarding

|

2 |

Abstracted from the Defense Acquisition Web site. Available at https://dap.dau.mil/aphome/ppbe/Pages/Default.aspx. Accessed August 10, 2010. |

|

3 |

Thomas Thurston, Program Manager, PPBE Processes and Training Programs, Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC). 2010. “PPBE Executive Training.” Presentation to the committee, April 21, 2010. |

TABLE 2-1 Current DoD Policies and Processes and Their Unintended Consequences

the employment of DoD Instruction 5000.02, the training of the acquisition workforce, or the assessment of acquisition workforce skills.4 One significant change incorporated in DoD Instruction 5000.02 is the increased emphasis on technology development and maturation.5 Previously, in DoD Instruction 5000.2, technology development was part of the pre-systems acquisition phase, focused more on concept exploration and Analysis of Alternatives (AoA).6 Many of the technology transition objectives and mechanisms cited in DoD Instruction 5000.2 have been retained in the current DoD Instruction 5000.02, but the pre-systems acquisition phase between Milestone A and Milestone B is now focused on reducing technology risk prior to contracting for Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD).

The entrance criteria for technology development at Milestone A now include the requirement for a technology development strategy (TDS) and full funding for the technology development phase of the acquisition program. The new DoD Instruction 5000.02 includes two additional mandates that need to be addressed in future Air Force acquisition programs. The instruction requires the acquisition authority to fund two or more competing prototypes of the system or key system elements and, when consistent with technology development phase objectives, to accomplish a Preliminary Design Review prior to Milestone B.7

Prototyping can certainly reduce risk if the prototype is truly representative of the production concept in function, performance characteristics, and emergent properties. Likewise, early design review will bolster confidence if it is accomplished at an appropriate level of detail and analytical rigor. The challenge to the acquisition community going forward is to take on these two mandates in a meaningful way. It may be that in this context “one size can’t fit all.” The funding and schedule allocations required to accomplish meaningful prototypes of more complex systems (e.g., aircraft and spacecraft) or systems of systems (e.g., battlespace management information technology, multiple autonomous systems) are likely to reach a point of diminishing returns.

|

4 |

DoD. 2008. Department of Defense Instruction. Subject: Operation of the Defense Acquisition System. 5000.02. Washington, D.C.: DoD. Available at http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/500002p.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2010. |

|

5 |

Ibid. |

|

6 |

USAF. 2008. Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) Handbook: A Practical Guide to Analysis of Alternatives. Kirtland Air Force Base, N.Mex.: Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) Office of Aerospace Studies. Available at http://www.oas.kirtland.af.mil/AoAHandbook/AoA%20Handbook%20Final.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2010. |

|

7 |

DoD. 2008. Department of Defense Instruction. Subject: Operation of the Defense Acquisition System. 5000.02. Washington, D.C.: DoD. Available at http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/500002p.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2010. |

Air Force Acquisition Improvement Plan

The only mention of technology in the Air Force Acquisition Improvement Plan (AIP) is a caution to warfighters to “resist the temptation to pursue high risk requirements that are too costly and take too long to deliver in favor of an incremental acquisition strategy that delivers most, if not all, requirements in the initial model with improvements added as technology matures….”8 It makes no mention of mechanisms by which technology will be developed and matured in the preacquisition phase, or, for that matter, in any phase of the acquisition life cycle.

Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction (CJCSI) 3170.01G describes the need for requirement support in concert with the resourcing and acquisition processes, to support the preacquisition program phase as well as Milestone B and beyond.9 However, CJCSI 3170.01G describes the need and directs the strong involvement of the requirements community in the preacquisition phase, but the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System (JCIDS) manual written to implement CJCSI 3701.01G provides insufficient “how-to” guidance on integration of the requirement into the acquisition and resource processes.

Competitive Prototyping

Although DoD and Air Force competitive prototyping policies and processes do focus on the preacquisition program phase, the DoD documentation does not provide clear methodologies, is silent on workforce training policies, and offers few metrics for tracking progress. The Air Force competitive prototyping policy, Air Force Instruction (AFI) 63-101, however, does provide processes, methodologies, and some measures for tracking progress.10 One shortcoming of AFI 63-101 is that it lacks a waiver process, whereas the Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009 (WSARA; Public Law 111-23) and DoD policy allow for waivers.

|

8 |

USAF. 2009. Acquisition Improvement Plan. Washington, D.C.: Headquarters United States Air Force. May 4. Available at http://images.dodbuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/acquisition-improvement-plan-4-may-09.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2011. p. 6. |

|

9 |

Joint Chiefs of Staff. 2009. Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction. CJCSI 3170.01G. March 1. Washington, D.C.: Joint Chiefs of Staff. Available at http://www.dtic.mil/cjcs_directives/cdata/unlimit/3170_01.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2010. |

|

10 |

USAF. 2010. Air Force Guidance Memorandum to AFI 63-101: Acquisition and Sustainment Life Cycle Management. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense. Available at http://www.af.mil/shared/media/epubs/AFI63-101.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2010. |

FINDING 2-1

The Air Force competitive prototyping policy, AFI 63-101, lacks a waiver process for competitive prototyping.

HISTORICAL GOVERNANCE RELATED TO TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT

Recently, several high-profile studies11,12,13,14 have discussed, at least tangentially, technology development. In addition, various policies, processes, and laws have been enacted over the years addressing technology development.15,16,17,18,19 Table 2-2 provides a summary of the committee’s assessment of the policies and processes discussed above and highlights specific unintended consequences or shortfalls in the context of technology development.

THE TRUST “DEATH SPIRAL”

As discussed in Chapter 1, in the subsection “The Right People,” forces external and internal to the technology development and acquisition processes have

|

11 |

NRC. 2008. Pre-Milestone A and Early-Phase Systems Engineering: A Retrospective Review and Benefits for Future Air Force Systems Acquisition. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. |

|

12 |

Assessment Panel of the Defense Acquisition Performance Assessment Project. 2006. Defense Acquisition Performance Assessment Report. A Report by the Assessment Panel of the Defense Acquisition Performance Assessment Project for the Deputy Secretary of Defense. Available at https://acc.dau.mil/CommunityBrowser.aspx?id=18554. Accessed June 10, 2010. |

|

13 |

Gary E. Christle, Danny M. Davis, and Gene H. Porter. 2009. CNA Independent Assessment. Air Force Acquisition: Return to Excellence. Alexandria, Va.: CNA Analysis & Solutions. |

|

14 |

Business Executives for National Security. 2009. Getting to Best: Reforming the Defense Acquisition Enterprise. A Business Imperative for Change from the Task Force on Defense Acquisition Law and Oversight. Available at http://www.bens.org/mis_support/Reforming%20the%20Defense.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2010. |

|

15 |

USAF. 2008. Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) Handbook: A Practical Guide to Analysis of Alternatives. Kirtland Air Force Base, N.Mex.: Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) Office of Aerospace Studies. Available at http://www.oas.kirtland.af.mil/AoAHandbook/AoA%20Handbook%20Final.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2010. |

|

16 |

Office of History Headquarters, Air Force Systems Command. 1979. History of the Air Force Systems Command—Calendar Year 1978. October 15. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Air Force. |

|

17 |

The Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (Public Law 101-510). More information is available at http://www.dau.mil/pubscats/PubsCats/acker/garci.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2010. |

|

18 |

The Department of Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund under Title X. More information is available at http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/10/usc_sec_10_00001705----000-.html. Accessed August 13, 2010. |

|

19 |

The Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-23). More information is available at http://www.ndia.org/Advocacy/PolicyPublicationsResources/Documents/WSARA-Public-Law-111-23.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2010. |

TABLE 2-2 Historical DoD Policies and Processes and Their Unintended Consequences

caused a major reduction in the numbers of people at the execution level, and large numbers of experienced, motivated, and skilled acquisition and technology professionals have left the government workforce, either voluntarily or involuntarily. In the words of the Commander of Air Force Materiel Command: “We have lost the ability to grade our contractors’ homework.”20

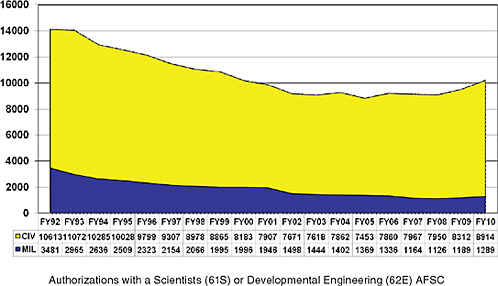

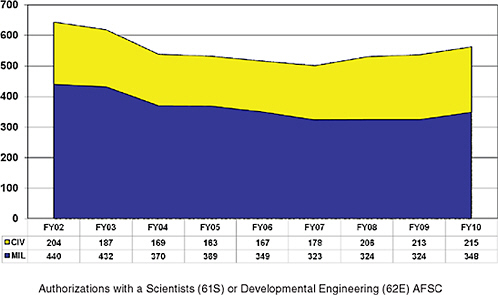

Additionally, the Air Force’s increased use of Total System Performance Responsibility (TSPR) as a contracting strategy resulted in a substantial loss of in-house technical expertise, as well as additional reductions of nontechnical personnel supporting the acquisition process. For example, Figures 2-1 and 2-2 illustrate the significant decline in the engineering workforce at both the Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) and the Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center (SMC).21,22 An additional complicating factor was a congressional cap on supporting Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs) that substantially reduced the outside technical support provided to some, but not all, of the Product Centers.23 During a period of increased programmatic and technical complexity, there has been a significant loss of the most experienced members of the acquisition workforce, without an adequate replacement pipeline. Additionally, without the necessary management emphasis, there has been “a systematic failure to update specifications, standards, and handbooks” that are essential to a successful acquisition system.24,25,26

Such significant personnel losses, combined with the atrophy of relevant guidance and documentation, have contributed to technology development and acqui-

|

20 |

Donald Hoffman, General, Commander, Air Force Materiel Command, USAF. Personal communication to the committee, July 15, 2010. |

|

21 |

Vincent Russo, Executive Director, Aeronautical Systems Center, United States Air Force. 2003. “An Overlooked Asset: The Defense Civilian Workforce.” Statement before the Committee on Governmental Affairs Subcommittee on Oversight of Government Management, United States Senate. |

|

22 |

Dwyer Dennis, Brigadier General, Director, Intelligence and Requirements Directorate, Headquarters Air Force Materiel Command, Wright-Patterson Air Force. |

|

23 |

GAO. 1996. Federally Funded R&D Centers: Issues Relating to the Management of DoD-Sponsored Centers. Washington, D.C.: GAO. Available at http://www.gao.gov/archive/1996/ns96112.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2010. |

|

24 |

Arthur Huber, Colonel, Vice Commander, Aeronautical Systems Center, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base; and Gerald Freisthler, Executive Director, Aeronautical Systems Center, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. 2010. “Aeronautical Systems Center Involvement in Applied Technology Councils.” Presentation to the committee, June 1, 2010. |

|

25 |

GAO. 2005. Information Technology: DoD’s Acquisition Policies and Guidance Need to Incorporate Additional Best Practices and Controls. Washington, D.C.: GAO. Available at http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04722.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2010. |

|

26 |

Information on workforce decline is also found in GAO. 2009. Defense Critical Infrastructure: Actions Needed to Improve the Consistency, Reliability, and Usefulness of DoD’s Tier 1 Task Critical Asset List. Washington, D.C.: GAO. Available at http://www.roa.org/site/DocServer/GAO_Defense_Infrastructure_17_Jul_09.pdf?docID=19801. Accessed July 22, 2010. |

FIGURE 2-1

Summary of Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) science and engineering workforce authorizations. SOURCE: Steven Butler, Former Executive Director, Air Force Materiel Command, USAF. Personal communication with the committee, August 24, 2010.

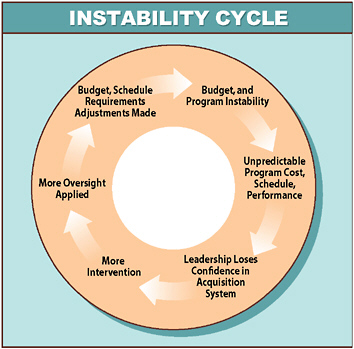

sition failures. Those failures have caused the Congress, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and higher headquarters in the Air Force to lose confidence in the executing organizations, and as a remedy, additional layers of oversight have been added.27,28,29 Although oversight can be value-added when conducted by knowledgeable people in a constructive manner, the very nature of such oversight tends to be based on distrust rather than on trust.

Ever-increasing oversight resulting from this lack of trust has greatly added to the workload of the people at the execution level, further reducing the time

FIGURE 2-2

Summary of Air Force Space Command (AFSPC) science and engineering workforce authorizations. NOTE: The Space and Missile Systems Center (SMC) transitioned from the Air Force Materiel Command to AFSPC (starting in fiscal year 2002). SOURCE: Donald Wussler, Colonel, Director, Development Planning, Space and Missile Systems Center, USAF. Personal communication with the committee, August 27, 2010.

available to them to manage technology development and acquisition programs responsibly.30 One result of this declining trust has been the passage of WSARA, directing independent assessments of Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) at the OSD-level.

A remedy—the reconstitution of an experienced and capable Air Force acquisition workforce that would include program managers, financial and contracting personnel, testers, and evaluators, as well as the technical staff to support program offices—has been initiated, but it will take much time and effort. There has been considerable emphasis placed recently on the reinvigoration of systems engineering; however, organic subject-matter experts within each of the domains are of equal importance. After two decades of atrophy, pipelines for the accession and

development of technically skilled and broadly experienced military and Civil Service personnel must be reestablished. This will require exceptional constancy and consistency of purpose from Air Force leadership.

Similarly, the reestablishment of trust will take time and is dependent on the redevelopment of a capable and experienced workforce, with the wisdom and discipline necessary to avoid the numerous acquisition problems that have plagued the process over the past 20 years. If appropriate and effective corrective action to rebuild the workforce is not taken, the result will be worsening levels of performance and an ever-more-hostile environment in which technology development and acquisition are conducted. Such a cycle can result in an ever-worsening “Death Spiral,” in which lack of trust and the resultant excessive independent oversight exacerbate programmatic instability, as shown in Figure 2-3.

FIGURE 2-3

The management and oversight systems of the Department of Defense generate significant program instability. SOURCE: Reprinted from Assessment Panel of the Defense Acquisition Performance Assessment Project. 2006. Defense Acquisition Performance Assessment Report. A Report by the Assessment Panel of the Defense Acquisition Performance Assessment Project for the Deputy Secretary of Defense. Available at https://acc.dau.mil/CommunityBrowser.aspx?id=18554. Accessed June 10, 2010.

FINDING 2-2

Lack of trust and increasing oversight of Air Force technology development and acquisition by the Congress, OSD, and Air Staff are making successful program execution ever more difficult.

THE “THREE R” FRAMEWORK

Building on Chapter 1, this chapter uses the “Three R” framework—that is, (1) Requirements, (2) Resources, and (3) the Right People—to track the Air Force’s preacquisition state in general and its experience with technology development specifically. Under “Requirements,” there are three focus areas: namely, the loss of Development Planning (DP), the decline in the effectiveness of Applied Technology Councils (ATCs), and the need to ensure that technology is mature enough to be incorporated in acquisition programs. Under “Resources,” the discussion emphasizes the lack of an Air Force-level science and technology (S&T) strategy. And under “The Right People,” the point is made that the workforce within the Air Force responsible for acquisition and technology development has atrophied to the point that it is now insufficient in both quality—that is, meaningful and relevant experience—and quantity.

Requirements

Previous studies suggest that the Air Force needs to do more effective planning in the earliest stages of programs, when ultimate cost, schedule, and technical performance are most malleable and thus most readily influenced. Recently, the report from the National Research Council referred to as the Kaminski report addressed this aspect directly, highlighting the need for systems engineering and the importance of the role that systems engineering plays in the major systems acquisition process.31 It also persuasively made the case for a return to the days of Development Planning, describing how prior to 1990 the Air Force used Development Planning to assess and integrate the various acquisition stakeholder communities, including especially combat commands, the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), and acquisition Product Centers. According to the Kaminski report, the use of Development Planning, coupled with systems engineering, resulted in the delivery of needed capability to the warfighter in a timely and affordable manner.32

In addition to Development Planning, there exist two other significant tools in the quest for clear, realistic, trade-off-tolerant, stable, and universally understood requirements. The first of these other tools consists of the once-effective ATCs, in

which warfighting commands, acquisition and logistics organizations, and laboratories managed the linkages between operational requirements, technology development, and systems acquisition—with the added benefit of the interpersonal relationships that developed, as well as the face-to-face communications which ensued. The second tool is the establishment and disciplined use of measures of technological readiness—that is, Technology Readiness Assessments (TRAs)—so that only when a technology is well defined and demonstrated does it make the transition from the laboratory world to become part of a major system acquisition program. Each of these—Development Planning, Applied Technology Councils, and Technology Readiness Assessments—is discussed below.

The Fall—and Rise—of Development Planning

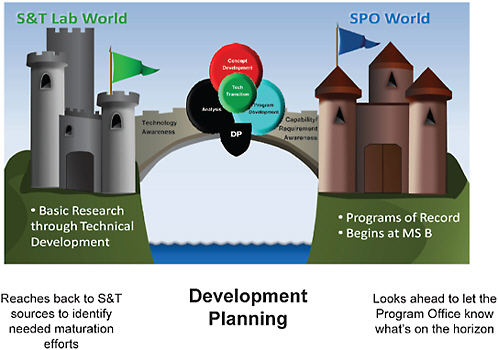

The need for clear, realistic, and stable requirements has long been understood. Shifting requirements are key drivers of program instability, causing late design changes that drive cost increases and schedule slippage, which in turn can lead to an erosion of political support for a program. To avoid these sources of program turbulence, there needs to be a clear understanding of requirements on the part of all stakeholders. This was in fact the role of Development Planning, in which an experienced cadre of Product Center acquisitions experts, knowledgeable of both warfighter requirements and the state of relevant technologies, facilitated this clear and mutual understanding of what was needed, and—equally important—what was possible (as illustrated in Figure 2-4).

Development Planning served the Air Force well. Until its demise a decade ago, many major weapons system acquisition programs were conceptualized, their requirements developed and refined, their technologies selected and matured, and their life-cycle costs accurately projected. Funding for Development Planning under Program Element 65808 fluctuated with the times, until it was eventually eliminated by Congress in 2001, with much of the DP expertise being scattered and eventually lost.33 The resulting absence of experienced staff members and mature processes did great damage to the understanding and development of requirements, while the past successes of Development Planning soon became mere memories in the minds of retirees and historians. It took only a brief time for the elimination of Development Planning to show up in major acquisition program failures, and numerous presenters to the committee pointed to the abandonment of Development Planning as a major contributing factor in the decline of Air Force acquisition excellence. One example of this decline is the E-10A Multisensor Command and Control aircraft that became a full-fledged program of record without any real AoA

FIGURE 2-4

The role of the Development Planning organization is to reach back into the science and technology (S&T) world to identify and assess the maturity level of technology necessary to meet operational requirements and to inform a System Program Office (SPO) about new technologies on the horizon. SOURCE: Dwyer Dennis, Brigadier General, Director, Intelligence and Requirements Directorate, Headquarters Air Force Materiel Command, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio. 2010. “Development Planning.” Presentation to the committee, March 31, 2010.

and that was also eventually canceled. The Kaminski report also addressed Development Planning and its important relationship to systems engineering, stating that the role of Development Planning was as follows:

[T]o employ various tools and techniques to define defense strategies, identify gaps in accomplishing those strategies, define concepts to address the gaps, use modeling and simulations or prototyping as ways to refine and test concepts, and provide early systems requirements to the systems developers for specific programs. Inherent in this role was the ability to understand the state of the art of the technical possibilities available from technology centers (laboratories, universities, industry, and so on), as well as to understand the needs of the user community (warfighters). These are all key attributes of a good pre-Milestone A systems engineering process. Successful programs discussed in Chapter 2 as “best practices” (e.g., C-5 and B-2) were originated during the “development planning” era.34

It is clear that in order to provide capability to the warfighter more effectively and affordably, the Air Force needs to revive Development Planning, and actions are being taken to do that (as shown in Figure 2-5). Still, there are reasons for concern. Although current efforts may be a good start, it became apparent to the committee that the Air Force would benefit from having a better understanding of previous DP processes that had been successful for so long. Some presenters to the committee appeared unaware of the Kaminski report’s recommendations regarding Development Planning. In addition, all presentations from Product Center DP chiefs indicated that their organizations suffered from high workload, limited personnel, and inadequate funding.

The Air Force is developing and reinvigorating its DP process. However, as in all organizations, Air Force decision makers would profit from a clearer understanding of their own past. There is very little new in the management of technology development: Indeed, the important lessons of technology development and acquisition management have been learned previously by the Air Force and, regrettably, many seem to have been forgotten. One such example involves an earlier Air Force DP process called Vanguard. The struggles—and the successes—of Vanguard 30 years ago closely parallel the challenges facing the Air Force today. Appendix D provides background information on the Vanguard process.

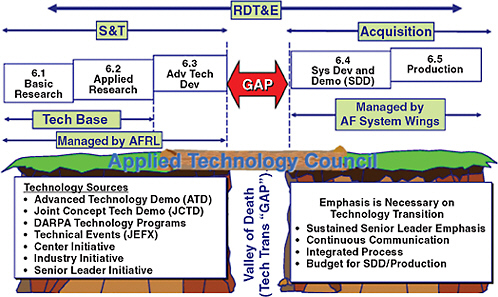

The Decline of Applied Technology Councils

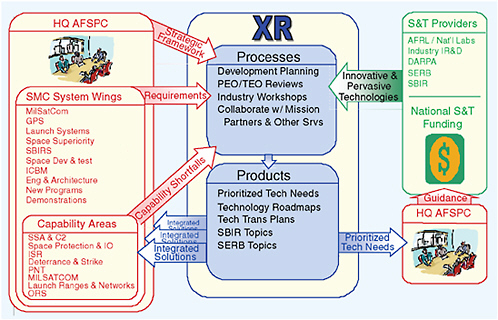

At one time, Applied Technology Councils were an effective tool for integrating warfighter requirements with acquisition priorities and technology maturation efforts. Hosted by Product Center commanders, ATCs were held quarterly and were attended by senior-level warfighters, top laboratory management, and high-level acquisition leaders. Combat commanders made clear their operational requirements, laboratory leaders explained what was feasible technologically, and the acquisition community set forth programmatic plans for matching requirements with new systems or subsystems. Priorities were established, funding was committed, and plans were made to transition technologies from the S&T world, across the Valley of Death, to operational success (as shown in Figure 2-6).

In some cases, ATCs remain important tools for managing the requirements-technology-acquisition interface. Through the research of the committee it became clear, however, that ATCs have, in some arenas, been allowed to deteriorate past the point of usefulness. The causes were many: New commanders sometimes had other priorities, while other, overtasked acquisition leaders began to let the intervals between ATCs grow, first to semiannual intervals, then to annual intervals, and then beyond that. When asked how often ATCs were held, one respondent told the committee, “Annually…. But sometimes we cancel them.” The staffs of some participating organizations soon required multiple pre-briefings, adding bureaucracy to the process and arguably watering down the frank dialogue. Eventually,

FIGURE 2-5

In the Air Force Space Command (AFSPC), Development Planning—called XR—links the needs of warfighters with the capabilities of the world of science and technology (S&T). NOTE: Operational input to the Space and Missile Systems Center (SMC) will come primarily through Headquarters AFSPC in its role as the SMC’s Major Command. For the purposes of this figure, nonmilitary S&T inputs would be grouped in the upper right with the other S&T input providers. SOURCE: Donald E. Wussler, Colonel, Director, Development Planning, Space and Missile Systems Center, USAF. 2010. “SMC/XR Function Brief.” Presentation to the committee, April 22, 2010.

the rank—and the perspective and the influence—of some ATC attendees declined: What had at one time been a three-star-level meeting became, in some situations, a conference between colonels, or lieutenant colonels.35,36

As with Development Planning, the decline of ATCs represents a significant setback in the pursuit of clear, stable, and realistic requirements. But unlike with the slow recovery of Development Planning, the reinvigoration of ATCs, where necessary, could be done quickly, and the benefits would be felt almost immediately.

FIGURE 2-6

Applied Technology Councils (ATCs) serve to bridge the Valley of Death technology transition gap between Budget Activities 6.3 and 6.4. SOURCE: Arthur Huber, Colonel, Vice Commander, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base; and Gerald Freisthler, Executive Director, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. 2010. “Aeronautical Systems Center Involvement in Applied Technology Councils.” Presentation to the committee, June 1, 2010.

FINDING 2-3

The decline of Development Planning and, in some quarters, the deterioration in the effectiveness of ATCs have greatly reduced the ability to integrate successfully the interests of warfighters, the S&T community, and acquisition leadership.

Assessing the Maturity of Technology

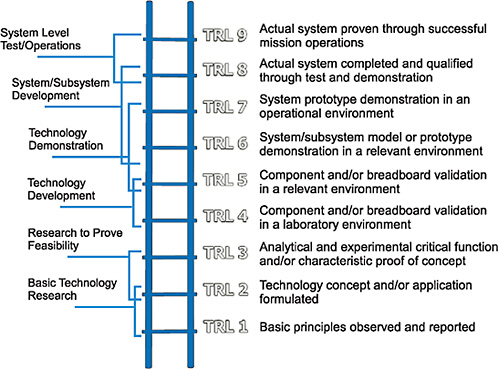

Technology maturity is a central factor in program risk.37 Objective measurement of Technology Readiness Level (TRL) assesses a technology’s maturity relative to its stage in the development cycle, whereas Manufacturing Readiness Level (MRL) is an analogous measure of manufacturing risk. Integration Readiness Level

evaluates the capability of a component or technology to be integrated into a larger system.38 An accurate appraisal of program risk requires considering all three of these factors, as all will ultimately affect a program’s likelihood of success or failure.

Industry has adopted technology development practices that are distinct from those used in the DoD. One particularly crucial feature is that successful technology developers separate technology development from product development. Technology is developed and matured first, and that is followed by the development of a product incorporating the new technology. These steps are not done concurrently.39 What industry has learned—and the Air Force is seemingly having to relearn—is that simultaneously developing new technology within an acquisition program is a recipe for disaster.

To avoid these problems, TRLs are used by industry and government agencies to assess systemic developmental risk by evaluating the maturity of technologies, and then, using that information, to determine readiness to progress from one development phase to the next.

Basic TRL definitions currently used by the DoD for hardware are shown in Figure 2-7. The Technology Readiness Assessment (TRA) Deskbook contains more complete descriptions and supporting information for hardware and software TRL definitions, along with descriptions and supporting information.40 The early application of TRL assessment was quite subjective, but the development of the TRA Deskbook41 makes significant advances toward the application of a uniform and objective assessment process. It will be instructive to observe the extent to which future assessments yield consistent programmatic results.

The requirement for Technology Readiness Assessments is contained in DoD Instruction 5000.02;42 the Office of the Director, Defense Research and Engineering (DDR&E), plays a key role in technology development and technology maturity assessments. The term “Technology Readiness Level” is often used as a proxy for technology maturity assessments; however, there is a full set of technology maturity metrics that go beyond TRL and include MRL and System Readiness Level (SRL).

|

38 |

James Bilbro and Kyle Yang. 2009. “A Comprehensive Overview of Techniques for Measuring System Readiness.” Proceedings of the 12th Annual Systems Engineering Conference, San Diego, Calif., October 26-29, 2009. Arlington, Va.: National Defense Industrial Association. |

|

39 |

Thomas Gehring, Program Manager, 3M Industrial and Transportation Business. 2010. “Technology Development and Innovation at 3M Company.” Presentation to the committee, June 7, 2010. |

|

40 |

DoD. 2009. Technology Readiness Assessment (TRA) Deskbook. Prepared by the Director, Research Directorate, Office of the Director, Defense Research and Engineering (DDR&E). Washington, D.C.: DoD. Available at http://www.dod.mil/ddre/doc/DoD_TRA_July_2009_Read_Version.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2010. |

|

41 |

Ibid. |

|

42 |

DoD. 2008. Department of Defense Instruction 5000.02. December 8. Available at http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/500002p.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2011. |

FIGURE 2-7

Department of Defense (DoD) hardware Technology Readiness Levels. SOURCE: Based on information derived from the Department of Defense and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The current DDR&E is placing strong emphasis on Development Planning and prototyping, as well as on the role of systems engineering in the developmental process, to include risk assessment.43

The Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009 established several new requirements relating to technological maturity that are summarized below. Among its other provisions, WSARA requires the following:

-

Periodic review and assessment of the technological maturity and integration risk of critical technologies of Major Defense Acquisition Programs

-

(MDAPs), and development of knowledge-based standards against which to measure technological maturity and integration risk;

-

An annual report to Congress on technological maturity and integration risk; and

-

A report to Congress on additional resources required to implement the legislation.44

The first annual DDR&E report45 to Congress on the technological maturity and integration risk of major DoD acquisition programs was submitted in April 2010. During 2009, DDR&E completed 11 Technology Readiness Assessments of MDAPs and 1 special assessment. The more robust technology readiness oversight role required by the legislation should serve to reinforce the initiatives taken recently by the Air Force to improve the technology maturation process.

A number of Government Accountability Office (GAO) studies in recent years have addressed technology development practices and the importance of technological maturity.46 A recent article states:

[A]lthough the Defense Department and the GAO remain at odds over the right technology readiness level (TRL) for new systems, the debate is unlikely to escalate. The Pentagon states that the two organizations continue to disagree on the meaning of mature technology before launching into system development. GAO advocates TRL 7, while the DoD prefers TRL 6. The DoD has taken the position that TRL 6 is adequate at milestone B.47

A Case Study on the Importance of Ensuring Technological Readiness: The Joint Strike Fighter

Overly optimistic Technology Readiness Assessments have been a root cause of cost and schedule performance problems on complex programs in the past. The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program, for example, has embraced many new technologies to provide the specified operational performance in a stealthy, multi-role fighter, producible at high production rates. Some notable technologies include a digital “thread” that controls the engineering, tooling, fabrication, assembly, and support systems for the aircraft and also controls several advanced subsystems and components. Although a large majority of the individual technologies incorporated into the F-35 have proven to be sufficiently mature, some of the Engineering and

|

44 |

Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-23, May 22, 2009). |

|

45 |

DoD. Department of Defense Report: Technology Maturity and Integration Risk of Critical Technologies for CY 2009. Washington, D.C.: DoD. |

|

46 |

GAO. 2006. Best Practices: Stronger Practices Needed to Improve DoD Technology Transition Processes. GAO-06-883. Washington, D.C.: GAO. Available at http://www.zyn.com/sbir/reference/GAO-d06883.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2010. |

|

47 |

Inside Defense News. 2010. “GAO, Pentagon Disagreement on TRLs Unlikely to Escalate.” Inside the Pentagon, April 22. |

Manufacturing Development cost increase has resulted from an unanticipated need for additional technology maturation. Although the increased cost for the EMD program cannot be attributed solely to the shortfalls in TRL, several technologies in retrospect were not at the required TRL 6, and those have contributed to the JSF’s delayed development and cost growth.

Public reports indicate that some of the cost increase for the EMD phase of the program has resulted from unanticipated technology maturation during full-scale development of the production configuration.48 The F-35 EMD program was structured to develop three variants with a high degree of commonality, and cost and schedule were based on assessments of Technology Readiness Levels above TRL 6. For example, one critical technology adopted for the JSF is the electro-hydrostatic actuation system used to power the flight controls. The contractor focused on developing this new technology and demonstrated a prototype subsystem in an F-16 before proposing to use it, but significant problems have been encountered nonetheless. In retrospect, more rigorous maturation of the high-power electronics and the specialized actuators in a representative environment was required for an appropriate level of confidence in the TRL for this complex subsystem.

FINDING 2-4

The absence of independent, rigorous, analytically-based assessments of Technology, Manufacturing, and Integration Readiness Levels will reduce the likelihood of successful program outcomes. Furthermore, despite the existence of clear and compelling examples to the contrary, the Air Force continues to initiate system acquisition prior to completing the required technology development.

Although expert opinions differ about when requirements should be baselined and about the appropriate assessment level to be used as a threshold for entry into EMD, concurrent evolution of technology and requirements should be the norm up to System Requirements Review (SRR.) At SRR, the capabilities of the selected technologies should be clear and the limitations that the technologies place on the operational requirements must be accepted, and either the technology development phase must be extended or the program terminated. One key SRR success criterion to be evaluated is whether the operational requirements can be met given the technology maturation achieved.

FINDING 2-5

After System Requirements Review, stable requirements and a well-defined operational environment are essential to successful technology insertion.

|

48 |

More information on the F-35 is available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lockheed_Martin_F-35_Lightning_II. Accessed September 2, 2010. |

FINDING 2-6

Some important technology insertion efforts have failed to mature due to the lack of (or subsequent loss of) a specific targeted program of record—for example, a new engine technology being developed for a proposed aircraft. Thus, a successful and useful technology may go dormant until a new program can be identified to host it. In this manner, even valuable technology advancements that cannot be inserted in a timely way into a program of record can be relegated to the “Valley of Death.”

FINDING 2-7

The array of technology possibilities always exceeds the resources available to pursue them. One result is that the technology planning process tends to over-commit available resources and does not always ensure that every technology investment has an executable plan (with a corresponding budget) that enables near-term production readiness.

Resources

Stable, clear, feasible and well-understood requirements are essential to the success of acquisition programs. Equally important are stable funding and robust processes that can reliably create satisfactory programmatic outcomes. As seen above, some of these processes are problematic. Some current processes are inadequately implemented, and others—like the ATCs—work for a time and then slide into disuse. Other processes do work—like the TRL system successfully used in industry and elsewhere in government (NASA, for example)—but for a variety of reasons fail to be used in a disciplined way, with risky and insufficiently proven technology comprising important parts of major programs. But the most significant—and surprising—process shortfall was the lack of an articulate and formal Air Force-level S&T strategy. To the contrary, a number of Air Force stakeholders asserted that there is no such overarching strategy, often unfavorably comparing the Air Force’s failure in this area to what they considered the more successful Future Naval Capabilities process of the U.S. Navy.49,50

Even a successfully resuscitated DP capability is not a substitute for an Air Force-level S&T strategy. The developmental planners at each Product Center strive to identify and prioritize technology development activities to match the require-

ments of their particular Major Command (MAJCOM) customers; nevertheless, the committee heard from multiple presenters that the Air Force does not attempt in any disciplined way to set technology priorities across the entire service.

A telling example of this need for an Air Force-level technology prioritization strategy can be found in the Technology Horizons study recently conducted by the Air Force Chief Scientist.51 Technology Horizons is the most recent in a succession of major S&T vision studies conducted at the Headquarters Air Force level. The study is an effort long overdue to help define key, priority S&T investments to provide the Air Force with the capabilities that it will need over the next 10 to 20 years. However, the study is focused on and written from the perspective of the S&T world. Although it identifies potential capability areas that might benefit from Air Force S&T activities, it does not answer the operationally oriented question of what future capabilities the Air Force needs to acquire. In other words, the technology opportunities described in the study need to be matched to the requirements established by operational Air Force organizations in order to optimize the Air Force’s S&T investments.

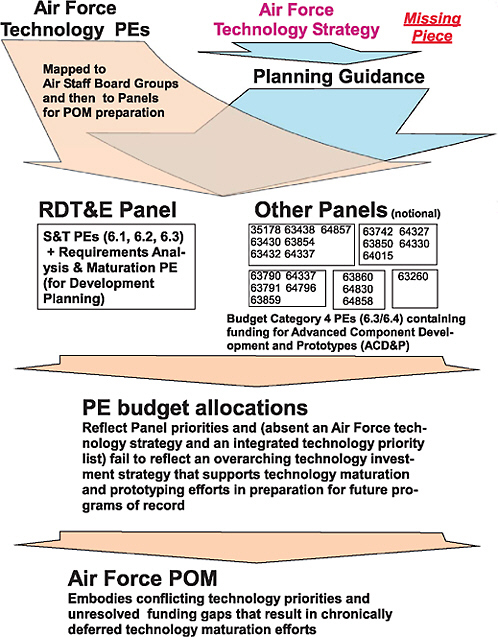

Similarly, ongoing efforts to reinvigorate ATCs that have fallen into decline will not substitute for an Air Force-level technology strategy. Balancing modernization needs and existing program support with available resources is a constant challenge. Pressures from oversubscribed Air Force budgets repeatedly drive short-suspense reprogramming actions on research and development funding, often with little in the way of rational analysis.52 Absent a technology strategy and prioritized list of technology maturation needs, the Air Force POM and budget process will not provide a solid foundation for future acquisition program success, as illustrated in Figure 2-8.

FINDING 2-8

The Air Force lacks an effective process for determining which technology transitions to fund.

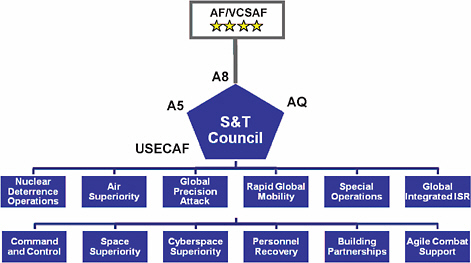

Nonetheless, a revived and rechartered ATC process could provide a forum for integrating MAJCOM capability needs with technology opportunities and technology maturation funding priorities. Consequently, the Air Force might consider means to link ATCs with MAJCOM representation to an Air Force-level S&T council, as shown in Figure 2-9, that provides top leadership consideration of all

|

51 |

Air Force Chief Scientist. 2010. Report on Technology Horizons: A Vision for Air Force Science and Technology During 2010-2030. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense. Available at http://www.airforce-magazine.com/SiteCollectionDocuments/TheDocumentFile/Strategy%20and%20Concepts/TechnologyHorizonsVol1_2010.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2010. |

|

52 |

Donald Hoffman, General, Commander, Air Force Materiel Command, USAF. Personal communication to the committee, July 15, 2010. |

FIGURE 2-9

A possible Air Force-level science and technology (S&T) council organization structure under consideration by an Air Force Tiger Team chartered to examine S&T strategy governance and strategic planning processes. The S&T council would potentially review and approve all S&T guidance and oversee technology transition progress. SOURCE: Michael Kuliasha, Chief Technologist, Air Force Research Laboratory. 2010. “AFRL Perspective on Improving Technology Development and Transition.” Presentation to the committee, May 13, 2010.

MAJCOM priorities, all laboratory S&T contributions, and all appropriate (6.3 and 6.4) funding. Such a process is needed if the Air Force is ever to have a strategic technology planning process.

Air Force leadership, after watching the number of funded Advanced Technology Demonstrations dwindle from 65 in 2000 to just 2 in 2009, recently chartered a Tiger Team to examine options for strengthening the S&T strategy planning process.53 The Tiger Team will identify opportunities for improvement in communication and governance that can lead to consistent S&T and transition priorities across all organization levels and to improved visibility and accountability of S&T needs and solutions. Tiger Team members are drawn from organizations across the Air Force and DoD and are assessing a range of possible S&T strategy governance options.

FINDING 2-9

Although the Air Force Chief Scientist has developed an “art of the possible” science and technology strategic plan for the 2010 to 2030 time frame, there exists no Air Force-level unifying strategy, inextricably linked to operational requirements, to guide decision making for science and technology investments.

FINDING 2-10

Successful technology development and technology transition require (1) integration of warfighter requirements with science and technology investments and systems acquisition strategies, and (2) close collaboration among all government and industry partners.

FINDING 2-11

MAJCOM ownership of Budget Category 4 Program Elements and the current Air Force Budget formulation process do not provide development planners with sufficient priorities for execution of maturation funding. At a higher level, the Air Force lacks an overarching strategy for technology development, or a process that involves key decision makers. As a result, there is no integrated view of warfighter needs and technological possibilities, and there is inadequate guidance for determining what technology transitions to fund.54

The Right People

The third of the “Three Rs”—the right people—is the most important. Without the right people, programs are more likely to fail, even when requirements and resources are addressed successfully. The phrase “right people” implies that there are enough people with the necessary knowledge and experience, in both government and industry, who are educated, trained, mentored, experienced, credible, empowered, and trusted to do the job at hand—that is, people who can, with the resources, meet the requirements and deliver needed capability to the warfighter.

Losses suffered by the Air Force acquisition workforce over the past two decades have been significant. Highlighted in the Kaminski report as well as in other reports were the ramifications of mandated reductions in acquisition personnel in the 1990s.55 Further, the Air Force Acquisition Improvement Plan states:

The Air Force acquisition workforce is staffed with outstanding men and women dedicated to their mission and their country…. However, while they perform top quality work, we have failed to adequately manage their professional development and maintain sufficient numbers of these experienced professionals. The result is an acquisition workforce eager and willing to take on any challenge, but in many cases one that is inadequately prepared for the task at hand. In some cases, the workforce lacks the necessary training or education to accomplish the mission. In others, the workforce simply does not have the depth of experience or specific skill sets necessary to accomplish the critical tasks.

As we better develop our workforce, we must also ensure it is appropriately sized to perform essential, inherently governmental functions and is flexible enough to meet continuously evolving demands. The size of the Air Force acquisition workforce, as currently defined, was decreased from a total of 43,100 in 1989 to approximately 25,000 in 2001 where it has remained since.56

The cumulative impact of all of the reductions and changes to the workforce can best be summarized in the following statements from a 2009 report of Business Executives for National Security (BENS):

Today the government too often finds itself with minimally experienced and transient individuals leading major acquisition programs, able to attract new people only after long delays, unable to couple rewards to performance, and with many senior positions simply unoccupied. Talented and dedicated people can often overcome a poor organizational structure, but a good organizational structure cannot overcome inadequate performance. When qualified people are combined with sound organizations and practices, success is virtually assured. The acquisition process, unlike most government pursuits, is a business function. It demands skills and talents that are far more common to the business world than to government and military operations.57

In building Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works, Kelly Johnson learned the importance of having good people and that quantity was no substitute for quality and

|

55 |

NRC. 2008. Pre-Milestone A and Early-Phase Systems Engineering: A Retrospective Review and Benefits for Future Air Force Systems Acquisition. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. |

|

56 |

USAF. 2009. Acquisition Improvement Plan. Washington, D.C.: Headquarters USAF. May 4, p. 4. Available at http://www.dodbuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/acquisition-improvement-plan-4-may-09.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2010. |

|

57 |

Business Executives for National Security. 2009. Getting to Best: Reforming the Defense Acquisition Enterprise. A Business Imperative for Change from the Task Force on Defense Acquisition Law and Oversight, p. 7. Available at http://www.bens.org/mis_support/Reforming%20the%20Defense.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2010. |

experience. To paraphrase Johnson: “You can’t stack enough average people high enough to equal one good person.” But that is exactly the situation facing the Air Force today. The loss of quality and experience over the past 20 years means that with few experienced people left to mentor newer hires, the Air Force must rely on large numbers of inexperienced and unproven acquisition professionals. One presenter to the committee spoke of a program to which the contractor had assigned 80 engineers, who stood stunned as a government review team arrived with 137 participants, most of them junior military and civilian employees.58 When the number of “checkers” nearly doubles the number of “doers,” it is hard to see that as a path to recapturing acquisition excellence.

Strong and innovative hiring efforts are under way and are aimed not only at encouraging new entrants to join the workforce, but also at capturing mid-career professionals from other agencies and industries. Those efforts are necessary and will pay off years down the road, but right now and for the foreseeable future, the Air Force is learning a hard lesson, similar to the lesson from the demise of Development Planning: An asset can be lost in the blink of an eye, but rebuilding it is the work of decades.

FINDING 2-12

The size and experience of the Air Force technology and development planning workforces are inadequate. Despite concerted efforts to fulfill the vision of a revitalized Development Planning function, recovery in this area will take a substantial period of time and a constancy and consistency of purpose from Air Force leadership.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Historically, successful acquisition programs have followed a dedicated period of technology development and maturation. In the late 1990s, Congress eliminated funding for key organizations and processes that enabled that technology development and maturation (e.g., the Product Center Development Planning Organizations, known as XRs). This resulted in the dispersal of the DP workforce, as resources were reassigned to other activities. The resultant technology development and maturation vacuum was, to some extent, filled by aerospace industry firms, advisory and assistance support contractors, and other ad hoc efforts, many of which lacked the focus and coherence of previous DP organizations and processes. Product Centers recognized the risk to program success caused by this situation

and began homegrown efforts to restore the XRs, but the resultant organizations have remained chronically underfunded, understaffed, and underequipped.59,60,61 Other efforts, such as the ATCs, at one time fostered timely and effective decision making regarding scarce technology maturation and funding. However, in some areas, ATCs and similar initiatives have been allowed to wither.

Meanwhile, poorly performing and failed programs have caused great frustration in the Congress and the OSD, leading to a serious erosion of trust of the Air Force’s stewardship of force modernization efforts. This distrust has resulted in statute- and policy-driven increases in program oversight during all phases of the acquisition cycle. This increased oversight is moving earlier in the process, being applied to preacquisition technology development activities (e.g., Material Development Decisions to Milestone B). One result is an increase in the number of “checkers” at the expense of the “doers”—an overemphasis on people performing review and oversight rather than executing the basics of technology development and program management. The “right people” means the right numbers of people, with the right experience and skills, doing the right things.

Increased oversight also has led, at times, to unrealistic program goals prior to Milestone B. Recently passed legislation and resultant DoD policy initiatives—for example, Section 852 of the 2008 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), competitive prototyping, DoD Instruction 5000.02, AIP, and WSARA—appear to address some of the negative impacts of the dissolution of DP organization and processes. However, sufficient funding levels are not yet evident, and the growing oversight environment, particularly pre-Milestone B, does not bode well for the full restoration of a robust preacquisition technology development capability.