4

The Recommended Path Forward

The preceding chapters provide the analytical foundation for recommendations contained in this chapter. Since the inception of the United States Air Force, its technological edge has been crucial to its success. This edge has been endangered over the past two decades, for the reasons cited in Chapter 2. Chapter 3 discusses characteristics common to organizations that do an exceptional job of specifying, developing, testing, and inserting new technology into their products or systems. These common characteristics, aligned with the “Three Rs”—(1) Requirements, (2) Resources, and (3) the Right People—the framework developed by the committee (see Box 1-2 in Chapter 1), can allow the Air Force to improve its ability to specify, develop, test, and insert new technology into its systems. This framework calls for clear, realistic, stable, trade-off-tolerant, and universally understood requirements; the resources needed to accomplish the job (including funding, together with policy and processes tailored for rapid technology insertion); and the right people (both in the government and as contractors) in the workforce and in charge.

Comparing the best practices exemplified in Chapter 3 with the shortfalls discussed in Chapter 2 leads to the seven key issues that the committee believes the Air Force must address in order to leverage quickly, correctly, and affordably the advanced technologies necessary to maintaining its warfighting edge. Table 4-1 summarizes these seven key issues, categorizes them in terms of the “Three Rs,” and for each issue identifies which specific criteria in this study’s statement of task (see Box 1-1) are addressed by one or more of the recommendations of the committee. The recommendations themselves are presented below in this chapter.

The seven key issues summarized in Table 4-1 are described in more detail

TABLE 4-1 Committee Recommendations Associated with the Seven Key Issues Identified in This Report

below. The description of each issue is followed by relevant findings (numbered in parentheses to match their numbering as presented in Chapter 2 or 3), and a recommendation associated with that issue. The chapter contains 17 of the study’s findings and the 7 recommendations of the study.1

KEY ISSUE 1

Freezing Requirements Too Early or Too Late in the Technology Development Phase Can Lead to a Mismatch Between Technology-Enabled Capabilities and Requirement Expectations That Significantly Reduces the Probability of Successful Technology Transitions

Imposing a large and rigid set of requirements at the outset of the technology development phase can create false expectations among stakeholders, who may assume that technology “miracles” will occur, enabling the desired capabilities. In such cases, rather than reconsidering requirement expectations when technologies do not live up to early promises, stakeholders holding to an inflexible “I-want-what-I-want” position force programs to take on significant cost, schedule, and performance risks in pursuit of technologies that may never mature. Conversely, programs that freeze requirement too late in the technology development phase—for example, after System Requirements Review—fail to provide stable, objective goals for assessing technology maturity and for containing cost and schedule slippage. Successful programs “viciously manage” requirements, beginning technology development with a reasonable and flexible set of commonly understood requirements.2 In these success stories, acquisition executives such as Product Center Commanders and Program Executive Officers ensure that a program’s cost-capability information is correct and current. As the true life-cycle costs and capabilities of new technologies become known, Major Command (MAJCOM) customers are willing to trade off requirement desires against the cost, benefits, and readiness of new technologies in order to achieve an optimum set of capabilities in a reasonable time and at an affordable cost.

|

1 |

The recommendations in this report apply to each of the three operational domains of the Air Force: air, space, and cyberspace. At the same time, each domain is unique due to its particular characteristics and the unique environments in which it operates. Several other findings besides those given here appear separately in Chapters 2 and 3. |

|

2 |

Douglas Shane, President, Scaled Composites. 2010. “Rapid Prototyping at Scaled Composites.” Presentation to the committee, May 13, 2010. |

FINDING (2-5)

After System Requirements Review, stable requirements and a well-defined operational environment are essential to successful technology insertion.

RECOMMENDATION 4-1

To ensure that technologies and operational requirements are well matched, the Air Force should create an environment that allows stakeholders—warfighters, laboratories, acquisition centers, and industry—to trade off technologies with operational requirements prior to Milestone B.

KEY ISSUE 2

The Lack of an Air Force-Level Science and Technology Strategy Leads to AFRL Efforts That May Not Support Desired Strategic Air Force Capabilities, and to the Fragmented Prioritization and Allocation of 6.4 Technology Transition Funds

If Air Force and industry efforts are to be focused on critical technology needs, then a process must exist at the corporate Air Force level to prepare and promulgate an Air Force science and technology (S&T) strategy. Unlike the Navy, whose Future Naval Capabilities process yields a strategic Navy-wide S&T plan overseen by a corporate structure consisting of research and development (R&D), program management, and operational stakeholders, the current Air Force process allows individual stakeholders, such as the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) and the MAJCOMs, to develop and fund their own priorities. Historically, the Air Force relied on mechanisms like Applied Technology Councils (ATCs) to bring together technology developers (i.e., AFRL), the operational community (i.e., MAJCOMs), and the acquisition community (e.g., the Product Centers) to reach agreement on which technology developments were most needed and would therefore be funded and incorporated into programs of record. Unfortunately, the Air Force has in some cases allowed ATCs to atrophy, weakening a viable process responsible for making strategic technology transition funding decisions. In addition, the Air Force Product Center Development Planning Organizations (XRs) have a 6.4 Program Element (PE) for Requirements Analysis and Maturation (RAM). But unlike research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) funding, which is prioritized and allocated by a single PE panel, 6.4 funding is managed by a diverse set of panels. Although this approach increases the likelihood that individual MAJCOM needs are met, it does not necessarily result in a global set of technology transition investments that address strategic Air Force priorities. In addition, once technology transition funds are distributed to the MAJCOMs, they tend to

use the funds to solve near-term problems that may be inconsistent with strategic Air Force priorities.

FINDING (2-8)

The Air Force lacks an effective process for determining which technology transitions to fund.

FINDING (2-9)

Although the Air Force Chief Scientist has developed an “art of the possible” science and technology strategic plan for the 2010 to 2030 time frame, there exists no Air Force-level unifying strategy, inextricably linked to operational requirements, to guide decision making for science and technology investments.

FINDING (2-10)

Successful technology development and technology transition require (1) integration of warfighter requirements with science and technology investments and systems acquisition strategies, and (2) close collaboration among all government and industry partners.

FINDING (2-11)

MAJCOM ownership of Budget Category 4 Program Elements and the current Air Force Budget formulation process do not provide development planners with sufficient priorities for execution of maturation funding. At a higher level, the Air Force lacks an overarching strategy for technology development, or a process that involves key decision makers. As a result, there is no integrated view of warfighter needs and technological possibilities, and there is inadequate guidance for determining what technology transitions to fund.3

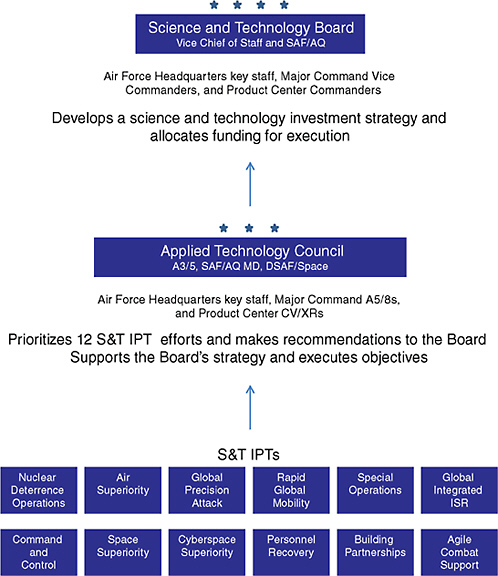

RECOMMENDATION 4-2

To enable (1) a more disciplined decision-making process and (2) a forum in

which all stakeholders—those from the science and technology (S&T), acquisition, and warfighting MAJCOM communities—can focus their attention jointly on critical technology development questions and then make tough strategy and resource calls efficiently at a level where the decisions are most likely to stick, the Air Force should consider adopting a structure similar to the Navy’s S&T Corporate Board and Technology Oversight Group and the Army Technology Objectives Process and Army S&T Advisory Group. A committee-developed notional organization for Air Force consideration (Figure 4-1) addresses this potential and is tailored to Air Force missions and organization. In addition, the Air Force should consider allocating funding for technology development, including funding for 6.4, or advanced component development and prototypes, to the Air Force Materiel Command and Air Force Space Command, unless precluded by law from doing so.

In the opinion of the committee, this recommendation to add another organization to the Headquarters Air Force does not diminish the statutory and mission responsibilities of the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Acquisition) (SAF/AQ)4 and is justified by the seriousness of the need. In the committee’s judgment, no other approach would meet the need to bring together the S&T, acquisition, and warfighting MAJCOM communities at a level that could make the difficult decisions. The fundamental premise of Recommendation 4-2 is the importance of technology to the Air Force, as described in the introductory paragraphs of Chapter 1 and reiterated in the introductory statements in Chapter 2. Findings 2-8 and 2-9 identify significant shortfalls in decision making for Air Force technology development and transition—that is, the lack of a process for technology transition and, at a higher level, the lack of a service-wide unifying S&T strategy to guide investments—which, in the judgment of the committee, need to be addressed. The structure proposed in Recommendation 4-2 would give SAF/AQ greater leverage to ensure that the right technology is being developed, matured, and transitioned. Furthermore, the cross-domain character of technology development, addressed in Chapters 1 through 3 of this report, presents challenges that the recommended S&T Board could address efficiently with a diverse set of stakeholders at the table. Finally, given the ever-increasing complexity and budget implications of new weapons systems, in the opinion of the committee the status quo is not acceptable.

KEY ISSUE 3

Current Air Force Funding and Business Practices for Pre-Milestone B Activities Are Inconsistent with Department of Defense Instruction 5000.02

Department of Defense (DoD) Instruction 5000.02 specifically states that processes, reviews, and milestones should be tailored for different program circumstances.5 However, the committee learned from numerous presenters that the acquisition community often treats DoD Instruction 5000.02 pre-Milestone B guidance as rigid, leading to long and sometimes costly technology insertion campaigns. For example, current policy requires Preliminary Design Reviews prior to Milestone B, even though in some cases (e.g., competitive pre-Milestone B contracts) the Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD) contractor has not been selected, and detailed system design information does not exist. In addition, expensive and lengthy competitive prototyping efforts are sometimes implemented to comply with acquisition directives when the best prototype may be known in advance of the competitive prototyping procurement.

FINDING (2-1)

The Air Force competitive prototyping policy, AFI 63-101, lacks a waiver process for competitive prototyping.

FINDING (3-1)

Tailored processes can enable rapid technology insertion.

FINDING (3-3)

A full understanding of the capabilities and limitations of the technology prior to committing to an acquisition program reduces the inclination to adopt unrealistic requirements.

RECOMMENDATION 4-3

Since DoD Instruction 5000.02 incorporates increased pre-Milestone B work, the Air Force should bring pre-Milestone B work content back into balance with available resources by some combination of (1) DoD Instruction 5000.02 tailoring and/or (2) additional expertise, schedule, and financial resources. Examples of expanded content include competitive prototyping, demonstrating technology in operationally relevant environments, and completing preliminary design prior to Milestone B.

|

5 |

DoD. Department of Defense Instruction 5000.02. December 8. Available at http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/500002p.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2011. |

KEY ISSUE 4

Technology Readiness Levels Must Be Accurately Assessed to Prevent Programs from Entering the Engineering and Manufacturing Development Phase with Immature Technology

The existence and definition of Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) are now commonly understood across the acquisition community. However, methods for assessing TRL maturity are not as well understood. This is a particular problem for the evaluation of technologies at the transition “tipping point,” where TRL guidance requires agreement on the definition of an “operationally relevant” environment. In many cases there can be considerable disagreement among well-intentioned experts on “relevance” criteria. Congress, through the Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act (WSARA) of 2009 (Public Law 111-23) assigned the Director, Defense Research and Engineering (DDR&E), the responsibility of conducting independent TRL assessments for selected Major Defense Acquisition Programs. In addition to concerns over the availability of DDR&E resources to accomplish this tasking, the ability to conduct independent TRL assessments needs to be vested in the Air Force acquisition system, initially to support non-Major Defense Acquisition Programs, and eventually to support all programs with DDR&E and congressional approval.

FINDING (3-6)

Independent, rigorous, and analytically based characterization of Technology, Manufacturing, and Integration Readiness Levels will lead to higher confidence and a greater likelihood of successful outcomes.

RECOMMENDATION 4-4

Knowledgeable, experienced, and independent technical acquisition professionals outside the program office should conduct technology, manufacturing, and integration assessments using consistent, rigorous, and analytically based standards. While WSARA requires this effort to be executed at the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) level, this organic capability needs to be developed and assigned to the Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) and the Air Force Space Command (AFSPC). Once this capability has been effectively demonstrated by the Air Force, legislative relief should be sought.

KEY ISSUE 5

Developing Technologies and Weapon Systems in Parallel Almost Inevitably Causes Cost Overruns, Schedule Slippage, and/or the Eventual Reduction in Planned Capabilities

The committee heard examples from numerous government and industry presenters about the pitfalls of entering the weapons system development phase while continuing to mature underdeveloped technologies. Because technology development often requires sudden moments of inventive inspiration, it is impossible to predict whether a technology will mature in time to meet important programmatic milestones. And even if the inspired moment does occur in time, the technology may not ultimately provide the desired performance or increased capability. It is therefore essential that unproven technologies be given sufficient time and resources to demonstrate their potential before entering into an acquisition effort that relies on that technology to achieve cost or performance goals. If the technology fails to meet expectations in time, the program is on the road to cost overruns and schedule slippage, with the program office needing to work with the operational community to adjust (i.e., reduce) capability expectations, or to seek additional funds and time to mature the technology (e.g., see the subsection “A Case Study on the Importance of Ensuring Technological Readiness: The Joint Strike Fighter” in Chapter 2).

FINDING (2-4)

The absence of independent, rigorous, analytically-based assessments of Technology, Manufacturing, and Integration Readiness Levels will reduce the likelihood of successful program outcomes. Furthermore, despite the existence of clear and compelling examples to the contrary, the Air Force continues to initiate system acquisition prior to completing the required technology development.

FINDING (3-5)

Decoupling technology maturation and system development has been proven to reduce overall risk dramatically.

RECOMMENDATION 4-5

To increase the likelihood of acquisition success, the Air Force should enter Engineering and Manufacturing Development (Milestone B) only with mature technologies—that is, with technologies at TRL 6 or greater.

KEY ISSUE 6

Weak Ties and Lack of Collaboration Within and Between Government and Industry Lead to Lack of Awareness of Government Priorities and of Industry’s Technology Breakthroughs

Laboratory, acquisition, and operational organizations in many cases pursue their own technology development and transition agendas. And nearly all organizations operate with only a modest understanding of industry investments in independent research and development (IR&D). Certainly “technology-push” efforts are always needed to capitalize on or respond to surprise breakthrough technologies, but the government must strive to strike a balance between “blue-sky” research and the “technology-pull” efforts driven by stated capability needs. The industrially funded Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) offers a useful example of tying laboratory technology-pull activities more closely to the acquisition and operational communities by requiring NRL researchers to compete for government funding with their industry counterparts. Collaborative government-industry forums, such as those sponsored by the Space and Missile Systems Center Development Planning organization, the Ground Robotics Consortium, and the National Small Arms Center, also serve to educate government decision makers about industry R&D plans and to motivate industry researchers to focus on technologies required to achieve desired future capabilities. Workforce training and incentives may be needed to establish such forums.

FINDING (2-6)

Some important technology insertion efforts have failed to mature due to the lack of (or subsequent loss of) a specific targeted program of record—for example, a new engine technology being developed for a proposed aircraft. Thus, a successful and useful technology may go dormant until a new program can be identified to host it. In this manner, even valuable technology advancements that cannot be inserted in a timely way into a program of record might be relegated to the “Valley of Death.”

FINDING (2-7)

The array of technology possibilities always exceeds the resources available to pursue them. One result is that the technology planning process tends to over-commit available resources and does not always ensure that every technology investment has an executable plan (with a corresponding budget) that enables near-term production readiness.

FINDING (3-2)

Successful technology transition is achieved by the participation of active senior service leadership, consistent priorities, and strong ties between commands responsible for science and technology, systems development and acquisition, and warfighting operations.

FINDING (3-4)

Collaborative practices between government agencies and industry can lead to successful technology insertion.

RECOMMENDATION 4-6

The Air Force should drive greater collaboration between warfighters (to include joint and coalition partners), laboratories, developers, and industry. One approach is to establish collaboration forums similar to the Ground Robotics Consortium and the Army Armament Research, Development, and Engineering Center’s National Small Arms Center.

KEY ISSUE 7

A Much Reduced and Inexperienced Development Planning Workforce Has Weakened the Technology Transition Bridge Between Laboratories, Product Centers, and Major Commands

Historically, much of the Air Force responsibility for technology development and maturation rested with the Product Center Development Planning Organizations. Processes such as Vanguard linked laboratory, Product Center, and operational stakeholders to manage Air Force technology investments collaboratively. In the past two decades, Development Planning (DP) budgets were significantly reduced and eventually eliminated, leaving no organizations explicitly accountable for technology transition, no concentration of funds to mature and transition technology, and no repository to capture and pass lessons learned on to following generations. In addition, as the experience base dwindled, failures began to rise, spawning a vicious cycle of failure, distrust, and the addition of layer upon layer of expensive DoD and congressional oversight. Fortunately, recent investments in the restoration of Development Planning, including the release of new SAF/AQ policies, reconstitution of the XRs, and restoration of limited technology transition funding by Congress, are continuing. While the Air Force has begun to take steps to repair the damage done to the DP function, more needs to be done, including increasing funding for, and managerial emphasis on, the DP organizations and

processes. Further, review of what was effective when the Air Force had a strong DP function would likely hasten its return.

FINDING (2-2)

Lack of trust and increasing oversight of Air Force technology development and acquisition by the Congress, OSD, and Air Staff are making successful program execution ever more difficult.

FINDING (2-3)

The decline of Development Planning and, in some quarters, the deterioration in the effectiveness of ATCs have greatly reduced the ability to integrate successfully the interests of warfighters, the S&T community, and acquisition leadership.

RECOMMENDATION 4-7

The Air Force should accelerate the re-establishment of the Development Planning organizations and workforce and should endow them with sufficient funds, expertise, and authority to restore trust in their ability to lead and manage the technology transition mission successfully.

CONCLUSION

From its inception, the Air Force has depended on advanced technology for an edge to overcome quantitative shortfalls—a comparative advantage that will likely become ever more important in a world of constrained defense budgets and diversified worldwide threats. Over the past two decades, the ability to specify, develop, test, and insert new technology into major Air Force systems was allowed to atrophy. More recently, the Air Force has recognized this deficiency and has started to reconstitute that capability; however, even more needs to be done. The recommendations in this chapter are intended to support and enhance that reconstitution effort and to help restore the Air Force’s qualitative technical edge. It is crucial to recognize, however, that restoring that technological edge will require a reversal of the lost trust discussed earlier in this report. By breaking that cycle of mistrust and returning to the fundamentals of the “Three Rs”—Requirements, Resources, and the Right People—the Air Force can return to the days when its superb technological leadership set the example for others to follow.