1

Challenges for the Intelligence Community

Measures to improve intelligence analysis have to adapt lessons from the behavioral and social sciences to the unique circumstances of analysts and their national security customers.

The primary missions of the intelligence community (IC) are to reduce uncertainty and provide warning about potential threats to the national security of the United States, the safety of its citizens, and its interests around the world. Decision makers—from the White House and Capitol Hill to battlefields and local jurisdictions around the globe—demand and depend on information and insights from IC analysts. The list of individual and agency customers is long, diverse, and growing. So, too, is the array of issues that analysts are expected to monitor: see Box 1-1; also see Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2009a, 2009b, 2009c).

STRUCTURE OF THE INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY

The IC is a complex enterprise with approximately 100,000 military and civilian U.S. government personnel (Sanders, 2008). Of this number, roughly 20,000 work as analysts, a category that includes both intelligence analysts who work primarily with information obtained from a single type of source, such as imagery, intercepted signals, clandestine human intelligence, diplomatic and attaché reporting, and “open source” or unclassified information and analysts who routinely work with information obtained from many sources (all-source analysts) (for a review, see Fingar, 2011). The distinction between these two types of analyst was once seen as fundamental. Today, it is widely understood that all analysts must use information and insight from multiple sources. For example, imagery analysts must use signals intelligence (SIGINT) and human intelligence (HUMINT) to clarify what they observe in imagery intelligence (IMINT).

|

BOX 1-1 2009 National Intelligence Strategy Objectives Summary MISSION OBJECTIVES (MO) MO1: Combat Violent Extremism Understand, monitor, and disrupt violent extremist groups that actively plot to inflict grave damage or harm to the United States, its people, interests, and allies. MO2: Counter Weapons of Mass Destruction Proliferation Counter the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and their means of delivery by state and non-state actors. MO3: Provide Strategic Intelligence and Warning Warn of strategic trends and events so that policymakers, military officials, and civil authorities can effectively deter, prevent, or respond to threats and take advantage of opportunities. MO4: Integrate Counterintelligence Provide a counterintelligence capability that is integrated with all aspects of the intelligence process to inform policy and operations. MO5: Enhance Cybersecurity Understand, detect, and counter adversary cyber threats to enable protection of the Nation’s information infrastructure. MO6: Support Current Operations Support ongoing diplomatic, military, and law enforcement operations, especially counterinsurgency; security, stabilization, transition, and reconstruction; international counternarcotics; and border security. ENTERPRISE OBJECTIVES (EO) EO1: Enhance Community Mission Management Adopt a mission approach as the expected construct for organizing and delivering intelligence support on high-priority challenges. |

As an integral part of the intelligence collection cycle, analysts both drive collection of and receive huge—and rapidly increasing—amounts of information. The collectors include both technical systems and human intelligence officers who obtain, process, and disseminate “raw” intelligence. The National Security Agency (NSA), for example, intercepts millions of

|

EO2: Strengthen Partnerships Strengthen existing and establish new partnerships with foreign and domestic, public and private entities to improve access to sources of information and intelligence, and ensure appropriate dissemination of Intelligence Community products and services. EO3: Streamline Business Processes Streamline IC business operations and employ common business services to deliver improved mission support capabilities and use taxpayer dollars more efficiently and effectively. EO4: Improve Information Integration and Sharing Radically improve the application of information technology—to include information management, integration and sharing practices, systems and architectures (both across the IC and with an expanded set of users and partners)—meeting the responsibility to provide information and intelligence, while at the same time protecting against the risk of compromise. EO5: Advance Science and Technology/Research and Development Discover, develop, and deploy Science and Technology/Research and Development advances in sufficient scale, scope, and pace for the IC to maintain, and in some cases gain, advantages over current and emerging adversaries. EO6: Develop the Workforce Attract, develop, and retain a diverse, results-focused, and high-performing workforce capable of providing the technical expertise and exceptional leadership necessary to address our Nation’s security challenges. EO7: Improve Acquisition Improve cost, schedule, performance, planning, execution, and transparency in major system acquisitions, while promoting innovation and agility. SOURCE: Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2009c). |

signals every hour (Bamford, 2002), and the National Counterterrorism Center processes thousands of names of potential terrorists every day (Blair and Leiter, 2010). In recent years, the collection, information processing, storage, and retrieval capabilities of the IC have improved dramatically, but the ultimate value of all this information still depends on the capabilities

of the analysts who receive it. They must consider new information against previous analyses, interpret and evaluate evidence, imagine hypotheses, identify anomalies, and communicate their findings to decision makers in ways that help them to fulfill their missions.

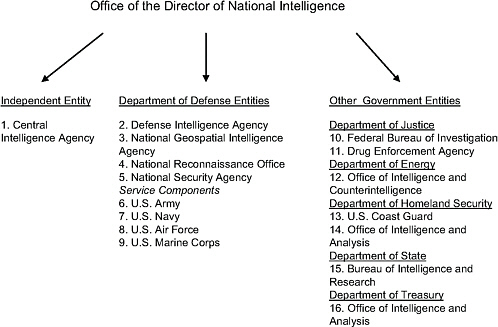

Most of the roughly 20,000 analysts in the IC work for one of 16 offices and agencies scattered across the federal government and overseen by the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). In addition, IC analysts work for three entities—the National Intelligence Council, the National Counter-terrorism Center, and the National Counterintelligence Executive—that are part of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI). One of the 16 agencies overseen by the DNI, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), is an independent agency. The other 15 entities are parts of different departments, agencies, and military branches: see Figure 1-1. IC member agencies range in size from the very small (e.g., the analytic component of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Office of National Security Intelligence) to the very large (e.g., the National Security Agency [NSA], the CIA, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Security Branch). The expertise required of analysts in each entity depends on their customers’ missions and priorities. For example, the Air Force and the Defense Intelligence Agency require more missile expertise than does the Department of Energy’s Office of Intelligence and Counterintelligence. Similarly, the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research and the CIA’s analytic component, the Directorate of Intelligence, require more country-specific political expertise than do the military services’ intelligence components.

These entities differ in missions and the desire for analysts trained and directly accountable to meet the agencies’ needs. The (literal and figurative) proximity of analysts and customers improves communication and trust between them, but having so many specialized intelligence units also creates problems. Chief among the problems are bureaucratic divisions that can isolate intelligence in “stovepipes” and lead to inconsistent standards, practices, and even terminology, which complicates interagency cooperation and confuses customers.

Broadly speaking, the nation’s confederated intelligence system has produced specialization at the expense of integration and collaboration. The IC’s inability to function as a unified team has been the subject of more than 40 major studies since the CIA’s establishment in 1947 (Zegart, 2007). The creation of the ODNI, after 9/11, was the latest and most serious effort in a long line of initiatives to transform the IC from a collection of semiautonomous agencies into an integrated intelligence system.

Both the strengths and the weaknesses of today’s IC structure must be recognized when considering ways to improve analysis. For example, efforts to reduce stovepiping should not undermine analysts’ ability to address the specific needs of their customers. The need for tailored intelligence is so

FIGURE 1-1 Members of the U.S. intelligence community.

SOURCE: Data from Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2009a, 2009b).

strong that no agency has advocated abolishing its dedicated unit, and some agencies that do not have such units continue to want them, despite recognizing the price paid for compartmentalization. The unsuccessful bombing attempt of a Northwest Airlines flight on Christmas Day 2009 showed that the IC is still struggling to solve the collaboration and integration problems (Blair and Leiter, 2010).

MISSION-RELATED CHALLENGES

The challenges facing the IC today are of two types: those specifically related to its mission and those facing virtually all complex organizations. Both types have to be considered when seeking to improve intelligence analysis.

The IC is still adjusting to the dramatic shift from the Cold War era to the very different demands of the 21st century. This shift requires moving from one core “target” (the Soviet Union and its allies) to many diverse targets, from existential threats to national survival to threats to specific U.S. targets, and from demands for general information (e.g., country A is providing certain types of weapons to country B or to insurgent group C)

to demands for “actionable intelligence” relevant to interdicting a specific ship, aircraft, or person. Discovering that the Soviet Union had nuclear weapons aimed at every U.S. city greater than a certain size created very different collection and analytic requirements than those needed to discover that a terrorist group plans to explode an improvised radiological device in a city, shopping mall, or school. The United States did not evacuate its cities in response to the nationwide threat of nuclear annihilation, but officials might choose to evacuate a shopping center if the IC reported a 10 percent chance of a terrorist attack during a specified period. Each of these changes in the world has implications for what IC analysts are expected to know and for how they do their jobs.

The Military and Other Customers

The military has long been the IC’s dominant customer, with intelligence needs for a wide variety of missions and officials, including the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, commanders of tactical operations, and designers of equipment and tactics. As a result, much of the IC has evolved to meet military requirements. This focus has, among other things, created a predisposition for the worst-case analyses needed by those designing equipment or preparing for battle (Powell, 2004). It has also created high tolerance for false alarms.

There has, however, been a steady increase in other U.S. government customers seeking the IC’s analytic support (Fingar, 2009), extending far beyond the military and other traditional users. The new customers range from the 18,000 state, local, and tribal law enforcement units that now may want terrorism-related intelligence (Perrelli, 2009); to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which wants disease-related intelligence; to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and others involved in emergency relief around the world. These customers ask different questions, require different intelligence support, and have different tolerance levels for false alarms and ability to plan for worst-case scenarios than the IC’s traditional military customers. Their questions require analyses on complex, interrelated domestic and foreign issues; with players from multiple countries and nongovernmental entities; and with a wide range of political, economic, social, and technical dimensions. These questions may need different perspectives than the more traditional transnational and country-specific perspectives (e.g., whether North Korea’s nuclear weapons program is viewed as a proliferation problem based in North Korea or as a North Korea problem with a nuclear dimension). In addition to meeting the needs of these new customers, the IC must simultaneously continue to meet the mission support needs of the Department of Defense (to which 8

of the 16 IC agencies belong), wherever and whatever they may be (e.g., from counterterrorism to disaster relief anywhere on the globe).

How well the IC meets these needs depends on the human capital embodied in its people and processes. The IC must recruit, select, train, motivate, and retain the right workforce, whose members must be adept at locating information, identifying potential collaborators, tapping expertise (inside and outside the IC), and using good analytic tradecraft. In order to support these needs, the IC has created such innovations as Intellipedia, A-Space, the Analytic Resources Catalog, and the Library of National Intelligence.1 In addition to these tools, internal deliberations on the best analytic techniques for different classes of problems, as well as deliberations about the individuals and procedures needed to apply them, are necessary to cultivate analytic skill.

These are all human activities, requiring expertise that resides in the behavioral and social sciences.2 These sciences include the scientific study of understanding, judgment, and collaboration and communication, within and across organizations. The remainder of this report deals with the opportunity to take advantage of this scientific knowledge to review current IC practices and develop improved ones. The committee is grateful for the invitation to apply the accumulated expertise of these sciences to the IC’s challenges and initiatives.

Open Sources

The role of open sources in intelligence analysis demonstrates the analytical changes that the behavioral and social sciences can inform. The IC has long recognized the value of open source intelligence (OSINT). From 1941 to 2004, the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) provided near real-time translations and republication of articles, speeches, and writings from foreign sources, giving information to intelligence officers, others in the U.S. government, reporters, and scholars. Since 1957, the U.S. Joint Publication Research Service has translated and published unclassified writ-

ings from around the world into English. In 2005, ODNI’s Open Source Center (OSC) absorbed and expanded FBIS’ capabilities distributed through its online World News Connection.

These services position the IC to benefit from the explosion of open-source information, especially for access to networked and cell-based threats. Nonetheless, there is still an ongoing debate about its value relative to clandestine information. Skeptics argue that “the intelligence community’s principal mission is to discover and steal secrets; relying on open sources runs counter to that mission” (Best and Cumming, 2007, p. 4; also Lowenthal, 2009; Mercado, 2005; Sands, 2005; Steele, 2000; Thompson, 2006). This position may reflect both experience and the intuitive tendency to place greater value on narrowly held information (Spellman, 2011).

Contrary to this skepticism, multiple government commissions have uniformly advocated greater use of OSINT (e.g., Commission on the Roles and Capabilities of the United States Intelligence Community, 1996; National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, 2004). In its call for sweeping changes in the IC, the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 described open information as “a valuable source that must be integrated into the intelligence cycle to ensure that United States policymakers are fully and completely informed” (Section 1052.a.2.). A few years later, the DNI Open Source Conference 2008: Decision Advantage convened participants from across the open source community to look at the spectrum of open source issues and best practices.3 Box 1-2 provides four noteworthy quotations from the debate over the use of clandestine versus open sources.

All these claims embody assumptions about analysts’ ability to extract and evaluate information from different sources. Open sources can be particularly useful when analyzing human behavior, such as economic, political, religious, and cultural developments. Moreover, open sources can strengthen the analytical process itself by providing cross-checks on information from clandestine sources and testing the soundness of common wisdom or emerging consensuses. The behavioral and social sciences provide a disciplined way of evaluating such assessments, complementing the intuitions and personal experience that inform them, as well as empirically evaluating their actual performance. The need for such science arises from the inevitable fallibility of human judgment and organizations.

|

3 |

See http://www.dniopensource.org/ [August 2010] for more information on the agenda of the 2008 conference. |

CHALLENGES FOR COMPLEX ORGANIZATIONS

Any organization that operates in a complex, fast-paced, high-stakes environment must find ways to learn and adapt, by shaping its personnel, organizational structure, and institutional culture to that changing reality. The IC shares many of the characteristics, strengths, and pathologies of other complex organizations. As a result, despite its unique mission and constraints, the IC stands to learn from research conducted in other settings on how to learn from experience, encourage collaboration, and improve communication with its customers.

Learning from Experience

The IC’s quickly changing, complex world makes it vitally important that it be able to learn from experience. However, as psychologists know (e.g., Brehmer, 1980), learning from experience is much harder than it seems.

One barrier is securing systematic feedback regarding analytical performance. Research has shown that outcome feedback is vital to correcting errors and reinforcing accurate performance (e.g., Kluger and DeNisi, 1996). However, IC analysts make predictions for events far in the future without the opportunity for feedback on how well they did and what factors account for their successes and failures. A second barrier arises from changes in world conditions that occur after analyses are made, some of which may be prompted by the analyses themselves (e.g., when national leaders take warnings seriously and act on them). Both the analysts and their customers must evaluate the analyses based on what they would have been if change in the world had been considered. Such counterfactual judgments face obvious challenges.

The behavioral and social sciences have developed ways to address these problems through statistical analyses of multiple forecasts. Such evaluations are common in medicine, which faces similar difficulties with long time frames and changed conditions. Done well, they can provide a picture not available with individual analyses. Sometimes, they show surprising results. For example, although weather forecasters are often criticized, their probability forecasts in the aggregate are accurate (for a review, see Murphy and Winkler, 1984). Decision makers who know about that accuracy (e.g., farmers, military planners) use them as a valuable input to their decision making. The forecasters’ accuracy reflects both their knowledge about the weather and their working in organizations that provide them with useful feedback and evaluate them fairly. The need to quantify confidence has been faced by members of other high-stakes professions, including medicine and

|

BOX 1-2 The Value of Open Source Information In support of the creation of the Central Intelligence Agency, Allen Dulles, who would become the agency’s first director, wrote (Dulles, 1947, p. 525): Because of its glamour and mystery, overemphasis is generally placed on what is called secret intelligence, namely the intelligence that is obtained by secret means and by secret agents. During war this form of intelligence takes on added importance but in time of peace the bulk of intelligence can be obtained through overt channels, through our diplomatic and consular missions, and our military, naval, and air attachés in the normal and proper course of their work. It can also be obtained through the world press, the radio, and through the many thousands of Americans, business and professional men and American residents of foreign countries, who are naturally and normally brought in touch with what is going on in those countries. A proper analysis of the intelligence obtainable by overt, normal, and aboveboard means would supply us with over 80 percent, I should estimate, of the information required for the guidance of our national policy. An important balance must be supplied by secret intelligence which includes what we now often refer to as “Magic.” A few years later, Sherman Kent (1951, p. 220) described the essential role of publicly available data: An overt intelligence organization … cannot hope to acquire all that it needs through its own open methods; there will always be the missing pieces which the clandestine people must produce. But on the other hand, the clandestine people will not know what to look for unless they themselves use a great deal of intelligence which they or some other outfit has acquired overtly. Their identification of a suitable target, their |

finance. This report examines the implications of this research for the seemingly similar problems faced by the IC’s analysts and customers.

One impediment to such learning is people’s unwarranted confidence in their own judgment and decision making (Slovic et al., 1972; Wilson, 2002). A large body of research also documents gaps between how people explain their decisions and statistical analyses of the processes that drive them. Quite often, as a result, people neither see the need for change (because they exaggerate how well they are doing) nor are able to make good use of experience. Thus, exhorting analysts to rely more on one factor and less on another means little if they misunderstand how much they are currently relying on those factors. Research with other high-stakes professionals finds troubling tendencies for experience to increase confidence faster than it increases performance (Dawson et al., 1993) and for people to exaggerate how well they can overcome conflicts of interest (Moore et al., 2005).

Scientific studies have identified other impediments to learning from

|

hitting of it, their reporting of their hit—all these activities exist in an atmosphere of free and open intelligence. A good clandestine intelligence report may have a heavy ingredient of overt intelligence. More recently, and 50 years after Dulles’s estimate that more than 80 percent of the nation’s needed intelligence would come from open sources, George Kennan, the architect of the U.S. policy of containment during the Cold War, offered an even larger percentage (Kennan, 1997, p. E17): It is my conviction, based on some 70 years of experience, first as a Government official and then in the past 45 years as an historian, that the need by our government for secret intelligence about affairs elsewhere in the world has been vastly overrated. I would say that something upward of 95 percent of what we need to know could be very well obtained by the careful and competent study of perfectly legitimate sources of information open and available to us in the rich library and archival holdings of this country. Much of the remainder, if it could not be found here (and there is very little of it that could not), could easily be nonsecretively elicited from similar sources abroad. In 2005, the Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction (2005, p. 365) concluded: Clandestine sources … constitute only a tiny sliver of the information available on many topics of interest to the Intelligence Community. Other sources, such as traditional media, the Internet, and individuals in academia, nongovernmental organizations, and business, offer vast intelligence possibilities. Regrettably, all too frequently these “nonsecret” sources are undervalued and underused by the Intelligence Community. |

experience (many detailed in subsequent chapters and in the committee’s companion volume, National Research Council, 2011). One prominent example is hindsight bias, the exaggerated belief after an event has occurred that one could have predicted it beforehand (Arkes et al., 1981; Dawson et al., 1988; Fischhoff, 1975; Wohlstetter, 1962). Analyses following Pearl Harbor, the 9/11 attacks, and other prominent events often lead to the conclusion that they should have easily been anticipated, had there not been a “failure to connect the dots.” However, research finds that accurate prediction is much harder than it seems in hindsight. The “failure to connect the dots” metaphor is itself a corollary of hindsight bias, which can complicate learning from experience by leading people to overlook other sources of failure, such as not collecting needed information or communicating it clearly.

A complement to hindsight bias is outcome bias, the tendency to judge decisions by how they turned out, rather than by how thoughtfully they were made (Baron and Hershey, 1988). However accurate an analysis, the

analysts cannot be held responsible for the decision makers’ actions that follow, unless they have failed to communicate the analysis effectively, including the confidence that should be placed in it. Research has documented these biases, the efficacy of different ways of overcoming them, and the methods for ensuring that analysts and policy makers are judged fairly when making tough calls in uncertain environments.

A third impediment to learning from experience is the “treatment effect” (Einhorn and Hogarth, 1978). Often, predictions lead to actions that change the world (a “treatment”) in ways that complicate evaluating the prediction. For example, a prediction of aggression may be wrong, but it may lead to actions that provoke aggression that would not otherwise have happened, thereby falsely confirming an inaccurate prediction.

As discussed below, the IC is acutely aware of the need to learn and adapt. Behavioral and social research provides mechanisms for evaluating the theoretical soundness and the actual performance of current and potential methods to foster good analytic judgment.

Collaboration and Communication

It is widely recognized that increasing collaboration and communication is key to the IC’s success in a rapidly changing, complex world. The mission statements of IC entities show the emphasis that the IC leadership places on these capabilities,4 as do its investments in innovations such as Intellipedia and A-Space. When the IC is the target of public criticism, the error most commonly cited is failure to communicate, within itself and with its customers. This was the case with the 9/11 attacks and more recently with the failure to warn of the Christmas Day 2009 bombing attempt. President Obama’s homeland security adviser, John O. Brennan (2010) said, “We could have brought it together, and we should have brought it together. And that is what upset the President.”

One of the biggest challenges in improving collaboration and communication within the IC is its organizational structure. As noted, the existence of 16 separate intelligence agencies (in addition to the ODNI) is a natural consequence of the specialized knowledge that each agency needs. However, these organizational structures create “silos” or “stovepipes” with boundaries that impede collaboration and communication.

These problems, too, are not unique to the IC. The failure to prevent the 1986 Challenger disaster stemmed from the inability of various subunits

in the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to integrate what each knew and from their different methods for processing information (Zegart, 2011). Research has identified these and other organizational factors that can impair information integration, as well as the efficacy of ways to overcome them. These barriers include the need for secrecy, “ownership” of information, everyday turf wars, intergroup rivalry, and differing skill sets—none of which is unique to the IC. For example, research shows how close-knit groups can become so homogeneous that they do not realize their limits to their in-group perspectives. Indeed, the IC has begun several efforts to overcome these barriers and to take advantage of its distributed expertise. Here, too, research has resulted in methods to evaluate the theoretical soundness of these measures, to evaluate their success, and to develop improvements (e.g., Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967; Weick, 1995).

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

The IC recognizes that throwing more money and people at problems or exhorting analysts to work harder will not meet its challenges. The only viable course of action is to work smarter. The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 created new opportunities to reduce organizational impediments to working smarter by empowering the Director of National Intelligence to transform the IC from a collection of semiautonomous special-purpose organizations into a single integrated enterprise.

In response to the need to explore new analytic processes and practices for the IC, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence asked the National Research Council to establish a committee to synthesize and assess evidence from the behavioral and social sciences relevant to analytic methods and their potential application for the IC: see Box 1-3 for the full charge. This report, along with a companion collection of papers, Intelligence Analysis: Behavioral and Social Scientific Foundations, is the committee’s response to that charge. Our report focuses on strategic analysis at the national level, although many of its findings may apply to combat environments where tactical or actionable intelligence may receive a higher priority or emphasis than strategic intelligence. Due to the unique circumstances of analysts, collectors, and decision makers often working side-by-side in combat environments, that application requires separate work beyond the scope of this committee’s charge. The same is true for analysis of the institutional structure of the IC. Our recommendations are meant to improve the quality of analyses within the constraints of the current structure.

Framed by this chapter’s introduction to the challenges for the IC, the rest of this report presents the behavioral and social science knowledge that can improve intelligence analysis. Chapter 2 looks broadly at two tasks central to the work of the IC, learning and evaluation. Chapter 3 identifies a

|

BOX 1-3 Committee Charge The panel will synthesize and assess the behavioral and social science research evidence relevant (1) to critical problems of individual and group judgment and of communication by intelligence analysts and (2) to kinds of analytic processes that are employed or have potential in addressing these problems. To the extent the evidence warrants, the panel will recommend kinds of analytic practices that intelligence analysts should adopt or at least explore further. The panel will also recommend an agenda of further research that is needed to better understand the problems analysts face and to establish a base of evidence for current and potential solutions. Finally, the panel will identify impediments to implementing the results of such research, especially new tools, techniques, and other methods, and suggest how their implementation could be more effectively achieved. In assessing the strength of the evidence, the panel will consider questions bearing upon the type of study (for example, case studies, large-scale field studies, laboratory studies, observational studies, or randomized control studies), the type of subject (for example, intelligence analysts, experts in areas similar to intelligence analysis, other experts, students, or other populations), and the attendant uncertainty (for example, robustness to different assumptions, confidence intervals and other measures, meta-analyses, exploration of alternative hypotheses or explanations of the data, extent of agreement in the scientific community). |

suite of proven scientific analytical methods available for application within the IC. Chapter 4 addresses the human resource policies needed to recruit, select, train, motivate, and retain employees able to do this demanding work. Chapter 5 considers how to optimize internal collaboration, allowing analysts to share information and learn from one another, thereby making best use of the community’s resources. Chapter 6 considers the communications needed for customers to inform analysts about their changing needs and for analysts to inform customers about the changing world. The final chapter presents the committee’s recommendations. The committee’s companion volume offers more details on the research summarized in this consensus report. The companion volume is designed to be suited to individual reading or courses incorporating the behavioral and social sciences in the work and training of intelligence analysts.

REFERENCES

Arkes, H.R., R.L Wortmann, P.D. Saville, and A.R. Harkness. (1981). The hindsight bias among physicians weighing the likelihood of diagnoses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66(2), 252-254.

Bamford, J. (2002). War of secrets: Eyes in the sky, ears to the wall, and still wanting. New York Times, September 8, Sec. 4, 5.

Baron, J., and J.C. Hershey. (1988). Outcome bias in decision evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 569-579.

Best, R.A., Jr., and A. Cumming. (2007). Open Source Intelligence (OSINT): Issues for Congress. U.S. Congressional Research Service. (RL34270), p. 4.

Blair, D., and M.E. Leiter. (2010). Intelligence Reform: The Lessons and Implications of the Christmas Day Attack. Testimony before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, 111th Cong., 2d sess. (January 20, 2010). Available: http://www.fas.org/irp/congress/2010_hr/012010blair.pdf [April 2010].

Brehmer, B. (1980). In one word: Not from experience. Acta Psychologica, 45(1-3), 223-241.

Brennan, J. (2010). Quoted in “Review of Jet Bomb Plot Shows More Missed Clues.” E. Lipton, E. Schmitt and M. Mazzetti. New York Times. January 17, 2010. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/18/us/18intel.html [September 2010].

Central Intelligence Agency. (n.d.). Strategic Intent. Available: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/additional-publications/the-work-of-a-nation/strategic-intent.html [October 2010].

Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction: Report to the President of the United States, March 31, 2005. Available: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/wmd/pdf/full_wmd_report.pdf [April 2010].

Commission on the Roles and Capabilities of the United States Intelligence Community. (1996). Preparing for the 21st Century: An Appraisal of U.S. Intelligence. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Dawson, N.V., H.R. Arkes, C. Siciliano, R. Blinkhorn, M. Lakshmanan, and M. Petrelli. (1988). Hindsight bias: An impediment to accurate probability estimation in clinico-pathologic conferences. Medical Decision Making, 8, 259-264.

Dawson, N.V., A.F. Connors, Jr., T. Speroff, A. Kemka, P. Shaw, and H.R. Arkes. (1993). Hemodynamic assessment in the critically ill: Is physician confidence warranted? Medical Decision Making, 13, 258-266.

Defense Intelligence Agency. (n.d.). Strategic Plan 2007-2012: Leading the Defense Intelligence Enterprise. Available: http://www.dia.mil/pdf/2007-2012-DIA-strategic-plan.pdf [October 2010].

Dulles, A. (1947). Memorandum Respecting Section 202 (Central Intelligence Agency) of the Bill to Provide for a National Defense Establishment. Statement submitted to Congress. Reprinted in the U.S. Congress, 80th Congress, 1st session, Senate, Committee on Armed Services, National Defense Establishment (Unification of the Armed Services), Hearings, Part 1, 524-528. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Einhorn, H.J., and R.M. Hogarth. (1978). Confidence in judgment: Persistence of the illusion of validity. Psychological Review, 85, 395-416.

Fingar, T. (2009). Myths, Fears, and Expectations. First of three Payne Lectures in the series “Reducing Uncertainty: Intelligence and National Security.” Available: http://iis-db.stanford.edu/evnts/5628/Payne_Lecture_No_1_Final—3-11-09.pdf [December 2009].

Fingar, T. (2011). Analysis in the U.S. intelligence community: Missions, masters, and methods. In National Research Council, Intelligence Analysis: Behavioral and Social Scientific Foundations. Committee on Behavioral and Social Science Research to Improve Intelligence Analysis for National Security, B. Fischhoff and C. Chauvin, eds. Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Fischhoff, B. (1975). Hindsight foresight: The effect of outcome knowledge on judgment under uncertainty. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 1(3), 288-299.

Kennan, G.F. (1997). Spy and counterspy. New York Times. May 18, E17.

Kent, S. (1951). Strategic Intelligence for American World Policy. Second Printing. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kluger, A.N., and A. DeNisi. (1996). Effects of feedback intervention on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254-284.

Lawrence, P.R., and J.W. Lorsch. (1967). Differentiation and integration in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12, 1-47.

Lowenthal, M.M. (2009). Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy. 4th ed. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Mercado, S.C. (2005). Reexamining the distinction between open information and secrets. Studies in Intelligence, 49, 2. Available: https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csistudies/studies/Vol49no2/reexamining_the_distinction_3.htm [May 2010].

Moore, D., D. Cain, G. Loewenstein, and M. Bazerman, eds. (2005). Conflicts of Interest. New York: Cambridge University Press, 263-269.

Murphy, A.H., and R.L. Winkler. (1984). Probability forecasting in meteorology. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 79(387), 489-500.

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. (2004). The 9/11 Commission Report. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, Inc. Available: http://www.9-11commission.gov/report/911Report.pdf [April 2010].

National Research Council. (2011). Intelligence Analysis: Behavioral and Social Scientific Foundations. Committee on Behavioral and Social Science Research to Improve Intelligence Analysis for National Security, B. Fischhoff and C. Chauvin, eds. Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. (2008a). United States Intelligence Community Information Sharing Strategy. Available: http://www.dni.gov/reports/IC_Information_Sharing_Strategy.pdf [June 2010].

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. (2008b). Vision 2015, A Globally Networked and Integrated Intelligence Enterprise. Available: http://www.dni.gov/reports/Vision_2015.pdf [July 2010].

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. (2009a). National Intelligence: A Consumer’s Guide. Available: http://www.dni.gov/IC_Consumers_Guide_2009.pdf [March 2010].

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. (2009b). An Overview of the United States Intelligence Community for the 111th Congress. Available: http://www.dni.gov/overview.pdf [July 2010].

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. (2009c). National Intelligence Strategy of the United States of America. Available: http://www.dni.gov/reports/2009_NIS.pdf [August 2010].

Perrelli, T. (2009). Statement of Thomas Perrelli, Associate Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice, Before The United States Senate Committee on The Judiciary Hearing Entitled “Helping State And Local Law Enforcement” Presented May 12, 2009. Available: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/newsroom/testimony/2009/perrelli_test_090512.pdf [July 2010].

Powell, C. (2004). Opening Remarks. Statement by Secretary of State Colin L. Powell Before the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee. September 13, 2004. Washington, DC. Available: http://www.usembassy.it/file2004_09/alia/a4091302.htm [April 2010].

Sanders, R. (2008). Conference Call with Dr. Ronald Sanders, Associate Director of National Intelligence for Human Capital. August 27, 2008. Available: http://www.asisonline.org/secman/20080827_interview.pdf [April 2010].

Sands, A. (2005). Integrating open sources into transnational threat assessments. In J.E. Sims and B. Gerber, eds., Transforming U.S. Intelligence. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Slovic, P., D. Fleissner, and W.S. Bauman. (1972). Analyzing the use of information in investment decision making: A methodological approach. Journal of Business, 45(2), 283-301.

Spellman, B. (2011). Individual reasoning. In National Research Council, Intelligence Analysis: Behavioral and Social Scientific Foundations. Committee on Behavioral and Social Science Research to Improve Intelligence Analysis for National Security, B. Fischhoff and C. Chauvin, eds. Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Steele, R.D. (2000). On Intelligence: Spies and Secrecy in an Open World. Fairfax, VA: AFCEA International Press.

Thompson, C. (2006). Open-source spying. The Times Magazine. New York Times. December 3. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/03/magazine/03intelligence.html?ex=1322802000&en=46027e63d79046ce&ei=5090&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss [July 2010].

Weick, K.E. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wilson, T.D. (2002). Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Wohlstetter, R. (1962). Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Zegart, A. (2007). Spying Blind: The CIA, the FBI, and the Origins of 9/11. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Zegart, A. (2011). Implementing change: Organizational challenges. In National Research Council, Intelligence Analysis: Behavioral and Social Scientific Foundations. Committee on Behavioral and Social Science Research to Improve Intelligence Analysis for National Security, B. Fischhoff and C. Chauvin, eds. Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.