3

The Phillips-Powderhorn Experience and the Allina Backyard Project

Mayor R. T. Rybak began his comments by acknowledging the efforts of Allina chief executive officer Richard Pettingill. It was his decision, Rybak noted, to move the headquarters of Allina to its current building in a part of Minneapolis experiencing some very deep challenges.

Looking at a map of the city of Minneapolis, Rybak explained that health disparities cluster in certain areas of the city. A look at unemployment rates across the city shows that they cluster in the same places where health disparities do. The same thing occurs with educational disparities. What this means, Rybak said, is that reducing health disparities is really about building holistic communities where a resident is entitled to live in a place where he or she can be fully sustained.

What does this mean from a public policy standpoint? It must first be recognized that any one of these issues cannot be tackled in isolation, but the initial focus needs to be on economic disparities, Rybak said. This includes a focus on housing, access to healthy food, and the ability to access health care when it is needed. Access to job training and job placement are other essential pieces of living a healthy life. Rybak noted that a workforce center is located only about half a block away from Allina headquarters.

Adequate housing is another major component of reducing health disparities. Mayor Rybak developed a housing trust fund that spends $10 million each year on affordable housing efforts. The city also uses the fund to purchase foreclosed homes and place new residents into those homes. The city offers foreclosure prevention sessions as well. He further noted that the

foreclosure problem across the United States is a huge human tragedy that requires policy makers to be actively involved in these issues.

Juvenile justice is another focus point in efforts to reduce health disparities. By launching a public health approach to youth violence, the entire community was brought together and a comprehensive approach focusing on prevention was created. This approach involves four key values. First, every young person in Minneapolis is supported by at least one trusted adult in his or her family or community. Second, intervene at the first sign that young people are at risk for violence. The city has stepped up efforts to enforce truancy and curfew laws. A curfew-truancy center where youth are sent also provides family support services; 80 percent of those youth sent to the curfew-truancy center never return. Third, refocus young people who have gone down the wrong path. Lastly, unlearn the culture of violence in the community. The outcome of these programs is that juvenile crime is down 40 percent over the past 2 years in Minneapolis. This is, Rybak said, an example of the importance of focusing on upstream factors.

Referencing the federal health care reform legislation then being discussed in the United States, Rybak observed that it is a “national disgrace” that children and adults in this country lack insurance coverage. At the same time, he said, the population needs to have dramatically different lifestyles. This means a focus on the physical activity aspects of communities. For example, Minneapolis has a bike center and hundreds of miles of bike trails, making the city the number two bicycling city in the United States (Portland, Oregon, is number one). It is essential to create and maintain walkable, sustainable communities.

Another example of making the physical aspects of communities friendlier is the Safe Routes to School initiative. Safe Routes to School is a national initiative that identifies ways in which schools and parent groups can find alternatives to busing to get students to and from school. Designating safe routes on which children may walk to and from school each day and including “human school buses” along the route have the added benefit of helping communities organize. A human school bus consists of parents and other adults who accompany with kids as they walk to school or who stand on their front steps and wave to the children as they walk by. Even a message wishing everyone a good day written in chalk on the sidewalk along where children walk can be a contribution to the human school bus.

The final frontier, Mayor Rybak said, is food: what people are putting in their stomachs. He noted that the local food movement is huge in this country and has led to the launch of a new initiative called Homegrown Minneapolis. This initiative involves creating more community gardens as well as increasing access to high-quality, affordable food in neighborhoods that currently do not have access to such products.

Taking this a step further, Rybak noted his wife’s involvement with an

effort to better connect children to nature. How can parents and kids be reconnected to the land? How can children be moved from “screen time” to “green time?” By connecting to the land, people become connected to their food and children are able to spend time in natural settings. To summarize, Rybak said, this is really about finding a comprehensive, holistic way to raise a family and thereby find a comprehensive, holistic way to create a community.

Following Mayor Rybak’s presentation, the audience was invited to ask questions. The first question was from participant Jim Hart of the University of Minnesota, School of Public Health. He asked how the mayor was being supported in his efforts to create holistic communities by the state and federal levels of government.

Rybak responded that, not surprisingly, the support is extraordinarily siloed, in that there is very little discussion across levels of government. For example, although federal and state support for housing is good, the support for youth violence prevention is very episodic. He noted that the current White House has created an urban policy position that is focused on the comprehensive nature of these issues. The mayor also commented on the importance of Michelle Obama planting a garden on the White House grounds.

Workshop participant David Pryor asked whether the city has embraced the mayor’s approach to change and whether evidence of lifestyle changes on the part of city residents has been detected. Rybak replied that although all of these initiatives are based in City Hall, they were created in partnership with the community itself. He noted that this is a two-way approach, in that community members must themselves participate in the local food initiative and in exercise. Health care reform cannot be expected to be successful without also focusing on changing individual behaviors, he said.

Sanne Magnan, Commissioner of Health for the state of Minnesota, thanked the mayor for his efforts in helping Minneapolis become one of the pilot communities for a new statewide effort called Steps to a Healthier Minnesota. She explained that she wants to expand this program across the entire state and wondered if lessons learned from the effort could be applied to the future expansion of the program. Rybak responded that the way that communities are built and laid out needs to be rethought. In some cases, this means making access to transit easier; in other cases, this means greater access to different goods within a community. With the population aging, Rybak continued, infrastructure issues must be addressed at the level of Main Street. For example, housing for seniors could be created above a corner grocery store.

Workshop participant Helen Jackson Lockadell asked about strategies to involve the media in better covering the positive things happening in communities. The mayor noted that the media does not always pay attention to the comprehensive nature of these issues. Furthermore, he said that efforts to communicate with people are so much easier now because of new interactive social media such as Facebook and blogging. The need is to stop thinking only about traditional media and start thinking about communicating with people directly, Mayor Rybak commented.

Another workshop participant asked about provisions to use food stamps at farmers’ markets. She noted that it is very important for the HIV-positive people who she works with to eat healthy foods. However, it is difficult for them to access healthy foods such as grapes or blueberries because of the restrictions on food stamp usage. Rybak replied that an initiative is under way for farmers’ markets to accept payments through electronic benefit transfer. Efforts are also under way to work with grocery store chains to get them to sell more locally grown foods.

When another workshop participant asked the mayor about future efforts to have healthy and sustainable communities, he asked Gretchen Musicant, Commissioner of Health in Minneapolis, to respond. She described the broad network of community clinics in place that provide health care to residents without insurance. She also described a program that is part of the Allina Backyard Project. Portico Healthnet provides people help with connecting to care and to paying for that care. This effort is subsidized by the health care sector, and the hope is to grow this program throughout Minneapolis. However, Rybak noted, the dramatic cuts in health care being proposed at the state level will have a number of consequences for the health department in Minneapolis.

Roundtable chair Nicole Lurie asked the final question. The Allina Backyard Project has reshaped its neighborhood, and similar efforts are under way in North Minneapolis. She wondered what lessons have been learned about the right conditions to make these sorts of changes.

Mayor Rybak replied that good neighborhood capacity, such as local institutional support, is critical. For example, both Allina and Abbott Northwestern Hospital play this role in the Phillips-Powderhorn neighborhood. He also noted the need to be explicit about putting disproportionate help in the areas of the city with disproportionate need. Describing this as “heavy, heavy lifting,” Rybak emphasized that extraordinarily broad coalitions must be built and many, many more partners must be involved. The mayor also acknowledged that these efforts are difficult to carry out.

Gordon Sprenger is former president and chief executive officer of Allina Health Systems. He presented a historical perspective on efforts that have taken place in the Phillips-Powderhorn neighborhood and began by setting the context. In the mid-1990s, a law that was based on the popularity of health maintenance organizations was implemented in Minnesota. Essentially on the basis of the idea of managing risk, health systems were told that they needed to accept an integrated payment for a population base and manage it. Then, in 1995, 19 hospitals and clinics came together with a major insurance plan into an integrated system that they named “Allina” on the basis of the premise that they could align incentives. The plan was to take a single payment and bring it to an organization like Allina that could then reallocate resources between the provider side and the prevention side. (Although the law was passed, regulations were never approved. Today, most health care deliverers are not part of an integrated system.)

Allina wanted to be an innovator in improving the health of the communities that the organization served. In 1995, these communities were facing many challenges: an aging population, homelessness, suicide, homicides, divorce, stress, households led by single parents, and a changing work environment. All of these challenges led to numerous health and family problems for community residents.

Sprenger described two “ah ha” moments that he experienced at about this time. First, he realized that children were coming to the emergency rooms to be treated for rat bites. No one considered the fact that once the rat bites were treated in the emergency room, the children were going directly back to the same rat-infested homes.

Second, Sprenger described visiting a local park where he spoke to a young mother about whether she had immunized her child. The mother reported that what she was worried about was whether her child would be gunned down in the park, not whether her child was immunized. She was thinking of survival, in other words, and he was thinking about long-term health. This disconnect led to Allina’s efforts to solve some of these problems.

Although several corporations and other organizations were operating individual programs within the Phillips-Powderhorn community, no focused cross-agency effort and no comprehensive plan were in place, so a joint business-government-neighborhood partnership was created. The members of the partnership pledged to raise $25 million to improve the community.

Sprenger emphasized here the importance of working in partnership with the other organizations and corporations. He quoted Albert Einstein, saying “The significant problems we face cannot be solved at the same

level of thinking we were at when we created them.” It was not enough to provide quality health care; what was needed was finding the primary causes of health care problems (violence, smoking, stress) and then finding ways to intervene.

One of the first things the partnership did was to engage in discussions with the police department to find a way in which they could work together to reduce crime and violence in the neighborhood. This effort led to a decrease in violent crimes from 1,227 in 1995 to 467 in 2008. At the same time, housing initiatives were initiated to replace and rehabilitate existing housing on the 14 most blighted blocks.

Other efforts included violence prevention; the creation of protocols to treat victims of abuse; and the establishment of an on-site family service center at a local elementary school that provided health care, social services, and mental health services to children and families. Sprenger offered asthma as an example. Because kids suffering from asthma have high rates of absenteeism, provision of on-site health care services for treatment of asthma resulted in decreased rates of absenteeism and improved school performance.

After realizing that 40 cents of every health care dollar goes to treat a tobacco-related illness, Sprenger decided to take this issue on as well. By contributing lobbying muscle, spending political capital, and working with other health care organizations, those efforts resulted in passage of legislation restricting where one could access tobacco products.

Many observers wondered what all of these efforts had to do with health. Many providers also felt that they were already short on resources to care for their sick patients, let alone to spend their few resources on upstream factors. Sprenger noted, however, that these social problems that the neighborhood residents experienced would become medical problems without some kind of intervention.

Other efforts funded by Allina Systems include

- Creation of the Phillips-Powderhorn Cultural Wellness Center (which will be described in more detail later in this summary).

- Establishment of a free shuttle service for elderly and Medicaid patients to reduce cancellation rates at clinics.

- Paramedic promotion of recreation safety through helmet awareness efforts in the parks to reduce rollerblading injuries.

- Free tattoo removal for former gang members.

- Creation of the Day One Project, a centralized call center with an updated database to help abuse victims find a bed in a shelter, which meant that an abuse victim needing help could locate a vacancy by making one rather than multiple telephone calls.

- Efforts to increase the number of children beginning school with complete immunizations by making shots available throughout the community in the No Shots, No School program, which led to an immunization rate of 98 percent, up from a rate of 60 percent 2 years earlier.

- Establishment of Park House, a day care center for HIV/AIDS patients, where social services as well as health care services are available, which helped prevent hospital emergency room visits.

A major accomplishment was the creation of a health careers partnership. Since 2000, more than 1,200 students have enrolled in the partnership and have graduated and gone on to career-track jobs. The Train to Work program was also created for an important business reason: to provide a future workforce for local hospitals. The program includes work readiness training and has a mentoring component.

Sprenger was chair of the American Hospital Association board at that time, so he had a strong platform from which to describe the program as he traveled throughout the country. He noted that Allina had invested $20 million to get many of the programs described above up and running. Although many were skeptical, Allina believed that their investment in the community was very much a business decision.

Richard Pettingill is the chief executive officer of Allina. He used the ongoing federal debate over health care reform to frame his comments and began his remarks by stating that the current debate is not about reforming health; rather, it is about reforming how the nation finances health care. The nation’s health care system is unaffordable, so a discussion of how to reallocate scarce resources is needed. It is essential, he said, that the dialogue in the debate be changed from one about health care to one about what health is. He suggested that to see meaningful health care reform, the 32 recommendations from the commissioned paper (Appendix A) need to be discussed and noted that health care reform needs to be seen as health promotion and prevention.

Pettingill related a story about the importance of determining what “health” means to people. Atum Azzahir hosted a community meeting where residents were asked the question, “How do you define health?” Having never been asked this question, after a stunned silence, the responses included “living my life without despair,” “I hope my kids have a future,” and “I know I am not dead, but I’m not certain I’m alive.” These definitions are fundamentally different from those of clinicians.

Pettingill likens the current situation to a perfect storm: health care reform legislation will provide incremental improvements and try to repair a system that is already broken. What is needed instead is investment in the design of an entirely new system.

As an integrated delivery system, Allina has a board of directors that has challenged the organization to, as Pettingill said, “create a revolution in health care.” It is not enough to tinker around the edges, the board emphasized. The organization should be “at the forefront of that revolution.”

Although acute and episodic care will always be an important part of the Allina system, now the emphasis is more on going upstream to focus on wellness, prevention, and chronic disease management. An electronic information system is also an important component of the organization so that the care received can be measured.

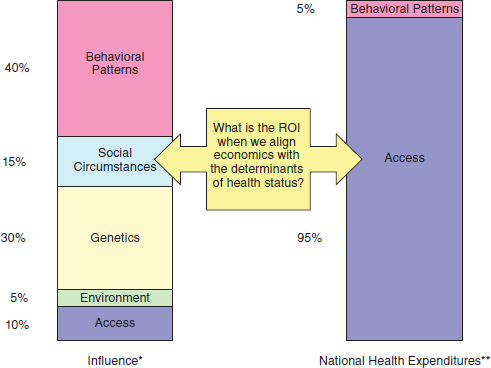

One example of how such an electronic information system can be used can be seen in a project launched by Allina in New Ulm, Minnesota, a community of 17,000 residents. The goal is to eliminate heart attacks in 10 years. A community cardiac risk assessment is under way for 10,000 of those residents. Then, moving upstream, residents at risk of cardiac arrest will be placed in a model of care that includes prevention, wellness, and chronic disease management. This is a change in how models of providing care get rewarded because prior to this, Allina would have been paid only for providing care to a heart attack patient in the emergency room. Scarce resources need to be reallocated to focus on social circumstances and behavioral issues (Figure 3-1). Rather than investing resources solely on health care access, investments in improving the determinants of health status are needed.

Pettingill also raised the question of what it means to be a not-for-profit organization with a tax exemption. He described a meeting of community leaders where charity health care was discussed, noting that Allina provides free care in the community worth $135 million. Pettingill noted that the business community suggested that it, the business community, should be the one claiming that benefit, because Allina builds the free care into its rate structure system that then gets passed to the private sector.

This discussion led to the formation in 2008 of Allina’s Center for Healthcare Innovation. Encompassing three projects—the Heart of New Ulm, the Backyard Initiative, and the Allina Patient Safety Center—the center’s purpose is to advance initiatives that improve overall health and well-being in the communities that Allina serves. These initiatives, in turn, will lead to the creation of national models that can be replicated locally. Allina is investing $100 million over a 5-year period in the Center for Healthcare Innovation. The center will also include a research component, in conjunction with the University of Minnesota’s School of Public Health.

Pettingill described the neighborhood where the Backyard Initiative

FIGURE 3-1 Aligning expenditures with determinants of health (* = McGinnis et al., 2002; ** = Brown et al., 1992).

is based. The neighborhood has a population of 45,000 people and high rates of unemployment, poverty, and subprime mortgages. At the same time, 50 not-for-profit organizations are present in the neighborhood, so resources are available. The real challenge is to get these organizations to collaborate, not compete, and to direct the limited resources in the same direction. The Backyard Initiative also has a strong Residents Council and buy-in from community businesses. The police department and the city public health department are both partners with the community as well. The role of Allina is to be a convener of people and to be a collaborator with the organizations.

The Backyard Initiative has a strong focus on prevention. For example, a childhood visual acuity screening was held in the neighborhood. Seven hundred children were screened, and 20 percent of those children needed—but did not have—corrective lenses. Clearly, this will affect the academic achievement of that 20 percent. Similarly, it is estimated that 50 percent of the children in the neighborhood have never had a dental exam. This, too, will affect learning, Pettingill explained.

Another partner of the Backyard Initiative is the Minnesota Early

Learning Foundation. A new project, the Early Learning Initiative, is being launched. Its goal is to encourage literacy in prekindergarten children. This, in turn, will affect graduation rates, incarceration rates, and health status. A health risk assessment effort is also linked to the Early Learning Initiative so that preschoolers who need visual and dental care can access it early in life.

Still needed in the neighborhood, Pettingill said, is a medical home as well as a social home. This will involve further partnering to ensure access for residents to the medical care delivery system, the public health system, the educational system, the social system, the social services system, and the economic system.

Sanne Magnan is the Commissioner of Health in Minnesota. Her presentation focused on (1) health care reform efforts in Minnesota and how those efforts have affected health disparities; (2) efforts and priorities at the state level to reduce health disparities via Minnesota’s Eliminating Health Disparities Initiative (EHDI), launched in 2001; and (3) working with policy makers to reduce health disparities.

Sanne Magnan began her comments by describing the strengths of the state of health care in Minnesota. She noted that the health plans in the state (e.g., Medica, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota, HealthPartners, and UCare) are required by law to be nonprofit. The state also has many integrated health care organizations, as well as a strong community clinic system and safety net system. In relation to the situations in other states, Minnesota has some of the highest-quality health care and some of the lowest health care costs in the nation, Magnan said. At the same time, every dollar that goes toward health care costs takes dollars away from other determinants of health, such as prevention, healthy behaviors, education, and affordable housing.

Minnesota’s health care reform law, passed in 2008, begins with an investment in public health and prevention through a statewide health improvement program. Initially called the Statewide Health Promotion Program, it built upon the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Steps to a Healthier U.S. model. State legislators, however, wanted to focus on health improvement rather than promotion, so the name was changed to the Statewide Health Improvement Program (SHIP). SHIP aims to help reduce the burden of chronic disease by focusing on the two leading preventable causes of illness and death: tobacco use and obesity. Through a competitive grant process, funding for SHIP was awarded to local public

health agencies (community health boards) and tribal governments. SHIP now covers all 87 counties in Minnesota and all tribal regions whose governments accept state funding.

SHIP focuses on making upstream changes to policies, systems, and environments to reduce tobacco use and exposure and to increase physical activity and good nutrition. Making those upstream changes is critical, Magnan said. Although improving the health care system is a worthy goal, if the only thing that happens is that more people enter the health care system to receive treatment, nothing is really solved. Upstream investments like those made by SHIP can help prevent disease before it starts.

Other components of Minnesota’s health care reform efforts include improving transparency about the quality and cost of health care, the creation of a quality incentive program for providers, and the implementation across the state of medical homes, which link the primary health care system with resources available in the community. Another activity supported at the state level by the health department is implementation of health information technology. By implementing electronic health records, Magnan noted, it will be easier to collect race and ethnicity data. Currently, more focused approaches are needed to collect such data, and those data are desperately needed to inform the activities needed to address disparities. By legislative mandate, both SHIP and health care homes will be evaluated by how well disparities are decreased.

Eliminating Health Disparities Initiative Efforts and Priorities in Minnesota

One critical aspect of Minnesota’s EHDI is to invest in building leadership capacity within communities of color and Native American populations. The initial approach focused on the eight key areas listed in Box 3-1.

At the same time, the health department is making a conscious effort to move toward a focus on upstream factors and the social determinants of health. This upstream approach—rather than a focus only on the health care system—should assist with reducing multiple health disparities. Moving the focus upstream can maximize the funding available to reduce health

BOX 3-1

Eliminating Health Disparities Initiative (EHDI)

Statewide effort to eliminate disparities in 8 areas:

| Infant Mortality | Diabetes |

| Childhood/Adult Immunization | HIV/AIDS and STIs |

| Cardiovascular Disease | Breast/Cervical Cancer |

| Violence/Unintentional Injury | Healthy Youth Development |

disparities by reaching more people because by focusing only on the provision of services to individuals, only a limited number of individuals can be reached. For example, Minnesota has approximately 750,000 residents who are people of color or American Indians, yet the existing funding can reach only 55,000 individuals with direct services. Working upstream in policy, systems, and environmental changes to address healthy behaviors, education, job development, the environment, etc., will allow a greater impact on more people in the state. Minnesota’s Freedom to Breathe act is an example of an upstream policy initiative that begins to reduce health disparities. By mandating clean indoor air for all restaurants, bars, and institutions, workers and patrons are protected from secondhand smoke. This is true for people of any race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

Other particular initiatives are essential to reducing health disparities. For example, in addition to the areas listed in Box 3-1, reducing tuberculosis is listed as a priority in the EHDI legislation. Magnan also noted the importance of building social capital and enhancing social interconnections as a strategy to eliminate health disparities. One example of this can be seen in state efforts to improve emergency preparedness. These efforts led to meetings between public health officials and other community officials, such as chiefs of fire departments and chairs of school boards. These connections across organizations can assist in tackling a myriad of problems. The establishment and use of medical care homes are another way to increase social capital, link people with cultural resources, and enhance work to eliminate health disparities.

Sanne Magnan noted the importance of using language that policy makers (e.g., legislators) understand. For example, rather than talking about physical inactivity and unhealthy eating, which is what she called “public health speak,” talk instead about “obesity.” Discussing the increasing rates of obesity among U.S. children—the children people see on the streets and playgrounds in their communities every day—is much more compelling than describing the problem only in public health terms. The creation of community gardens with the involvement of families and children is another example of a compelling story for legislators.

Another important lesson learned about working with legislators is to focus on solutions that can solve multiple problems. For example, Minnesota is discussing using some of the same infrastructure for both SHIP and

emergency preparedness programs. Treating obesity as a disaster event or incident, like any other emergency, is an approach that could address many problems, Magnan explained. In addition, an infrastructure like that used for SHIP that focuses on policies, systems, and environmental interventions could be used to tackle other issues, such as alcohol abuse.

Finally, Magnan indicated that the use of economic data is also helpful when working with the legislature. She used the example of sharing with the legislature the economic consequences of tobacco use and obesity, explaining that unless these two health care issues are addressed, the annual cost of health care for the state could be as much as $3.4 billion.

All of the morning speakers (Cohen, Iton, Rybak, Sprenger, Pettingill, and Magnan) responded to questions. Jeff Levi asked the first question, which referenced the health care reform efforts going on at the federal level. He asked how the federal government could best support the positive efforts under way in Minnesota. He followed up by asking Magnan to address the role of prevention in Minnesota’s health programs.

Sanne Magnan responded by referring first to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in early 2009. That legislation included approximately $650 million for community-level health and wellness programs. She noted the importance of ensuring that those funds get to the local level for use in programs like the Steps to a Healthier U.S. program currently funded by the CDC.

Sanne Magnan also described the perception that the federal efforts in health care reform address only access to care and not the overuse and inefficiencies in the health care system. The National Priorities Partnership is one organization trying to bring to bear a framework that focuses on the problem of overuse. Palliative care and safety issues must also be addressed.

Reforming Medicare payment models is another piece of the federal effort that Magnan believes needs to be addressed. States like Minnesota, she said, are actually disadvantaged because of the way that Medicare pays providers.

Richard Pettingill suggested that the public health community needs to show some outrage to become actively involved in the health care debate. He noted that the book Freakonomics, in describing how people ascertain risks, describes a trade-off between hazards and outrage that must be balanced. The number of people who die each year of heart disease, for example, is an example of a risk with a high hazard but low levels of outrage. High levels of outrage (and a low level of hazards), on the other hand, occurs when a child dies because of a gunshot wound. What is needed, Pettingill said, is greater levels of outrage on the part of the public

health community. This outrage needs to be brought to the federal health care reform debate.

A representative from the Minneapolis Urban League asked the panel about the problem of the very small amount of resources available to communities of color. For example, she said, many children in Minneapolis eat hot Cheetos or other junk foods for breakfast. Is there a way, she wondered, to provide incentives to communities to encourage healthier eating? Will SHIP have a role in providing communities of color with incentives for living a healthier lifestyle? Magnan responded that one of the strengths of SHIP is that local communities will have a menu of interventions from which to choose.

A participant from the Association for Nonsmokers described her experience attending the state’s SHIP conference. She noted that some members of the audience see health care reform efforts to be a move toward socialism. Additionally, some participants at the conference expressed negative feelings about using taxpayer dollars to try to change individual behavior. In fact, some participants at the conference believed that attempting to change this behavior is not an appropriate role for government at all.

Magnan replied that this is an example of “democracy in action.” Consideration of community health requires both individual responsibility and community responsibility. For example, if a person wants to go walking outdoors, it is his or her responsibility to put on shoes and go out the front door. At the same time, however, if the community has no sidewalks, no streetlights, or high levels of crime, the responsibility becomes that of the community. Rather than seeing this as socialism, Magnan commented, this is just good public policy.

Joel Weissman, an afternoon speaker, offered his own examples of the critical link between individual responsibility and community responsibility. People will not go out walking, he said, unless the community makes it possible to go out walking. Weissman noted that many elderly people move to Florida because in their home states snow does not get shoveled from the sidewalks and they end up feeling trapped in their homes. It is possible, he said, to combine a focus on individual behavior with public policy.

Weissman is a backyard gardener, growing cherry tomatoes, blueberries, and raspberries, and discovered that his children and their friends were snacking from the garden. At the same time, he noted, they still like pizza and Cheetos as much as ever. So, only so much can be done to encourage individual responsibility without ensuring that opportunities exist as well. A person cannot eat healthy food without access to gardens, farmers’ markets, or good grocery stores.

Sarah Greenfield, a community organizer with Take Action Minnesota and Make Health Happen, asked about access to high-quality, affordable health care. Commenting that this was only one recommendation out of 32

in the commissioned paper by Larry Cohen, Anthony Iton, Rachel Davis, and Sharon Rodriguez, she asked if the changes that occur nationally or in the state because of health care reform would affect the public delivery of health care to the poor, the elderly, and other groups with limited resources.

Anthony Iton responded that it is imperative to consider health care an important social good. The goal is to align the incentives so that people understand that their own personal interests are inextricably tied to the health issues of others in their community. He noted that the current health care reform debate is really about payment reform rather than health care reform and that this is a frightening distraction from the real issues. It is essential, Iton said, to ensure that community-based prevention efforts are at the core of health care reform.

Larry Cohen noted that not everyone shares the perspective that prevention should be the centerpiece of health care reform. Other advocates feel that the emphasis on prevention is a distraction. Clearly, he said, one is not going to work without the other; the two groups of advocates must learn to work together.

Richard Pettingill, in response to Sarah Greenfield’s question, commented that it is essential to bring the mainstream health care delivery system into the debate as a collaborator with communities and public health officials. Rather than seeing the current efforts as either health reform or health care reform, it should be a dialogue that includes both health reform and health care reform.

Sam Nussbaum asked Sanne Magnan about the role of reducing waste and inefficiency in the health care system. He proposed that Minnesota could be a model for other states looking to reduce the cost of care, and asked Magnan to talk about efforts within the state to get costs under control.

In response, Magnan stated that Minnesota’s health reform efforts have three goals: first, to improve population health; second, to improve the health care experience for the consumer; and third, to improve affordability. As an example, she described the state’s efforts to create a system for high-tech diagnostic imaging (magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scans) across communities and health plans. Any patient who is given a high-tech diagnostic imaging test should have this information embedded in that patient’s electronic medical records. In this way, a system has been put into place to ensure that this valuable but expensive resource is being used wisely across communities.

Richard Pettingill offered a second response to Nussbaum’s question. Although Minnesota is ranked at the top of all states in terms of health status and educational achievement, it is also true that the state has a high tax rate. In comparison, Georgia has a very low tax rate but among the worst high school graduation rates in the country. Also, Medicare reimbursement

rates are higher in Georgia than in Minnesota. At the same time, the quality of health care is lower in Georgia than in Minnesota.

Nicole Lurie noted that the federal stimulus funding contains investments in areas that directly affect health outcomes, such as early childhood education and housing. Her perspective is that these should be considered important health investments.

Joel Weissman asked about the role of evaluation in establishing medical homes. Magnan explained that they relied upon a very participatory process that first involved setting up criteria and outcomes. She noted that it is essential to look at outcomes because of the need to be held accountable for better health and improved affordability.

Roundtable chair Nicole Lurie asked the final question, which was whether health care organizations such as health insurers and hospital systems should be allowed to have nonprofit status. She explained that there is a national movement among public health leaders to request evidence for the community benefits that a health care organization provides in order to determine that it is providing an adequate amount of community care. Thus, the organization must provide concrete evidence in order to maintain its nonprofit status.

Gordon Sprenger said that his view is that the difference between for-profit and nonprofit systems is what the organization does with the profits. In a for-profit organization, those profits go back to the shareholders; in a nonprofit organization, those profits should be invested back into the organization itself and into the community that it serves. He noted the importance of national leadership on the question of how resources are allocated and said that this is at the core of health care reform.

Sprenger also mentioned the role of philanthropic organizations. Explaining that philanthropies have few constraints on how funding is allocated, he said that as health care reform continues to be evaluated, the private foundation environment also needs to be examined.

Mike Christensen, a member of Mayor Rybak’s staff, also responded by saying that public health leadership needs to adopt a new “fundamentalism” about reducing health disparities in Minnesota. He noted that of the health disparities that Sanne Magnan described in her presentation, many involve sex or violence behaviors. These behaviors, in turn, can lead to despair, hopelessness, and a lack of future orientation. Low-income urban populations need more than a new brochure, Christensen said; they need career ladders and affordable housing. Society needs to “get real about the interventions,” he commented. He also explained that Allina had tripled the amount of hiring that it does from the surrounding neighborhoods, and that Wells Fargo Mortgage had invested $35 million in housing in the surrounding area. In conclusion, Christensen said, these are the kinds of interventions that need to happen.

Brown, R., J. Corea, B. Luce, A. Elixhauser, and S. Sheingold. 1992. Effectiveness in disease and injury prevention estimated national spending on prevention—United States, 1988. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 41(29):529–531.

McGinnis, J. M., P. Williams-Russo, and J. R Knickman. 2002. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Affairs 21(2):78–93.