Summary of Recommendations

C1 Build the capacity of community members and organizations.

C2 Instill health and safety considerations into land use and planning decisions.

C3 Improve safety and accessibility of public transportation, walking, and bicycling.

C4 Enhance opportunities for physical activity.

C6 Support healthy food systems and the health and well-being of farmers and farm workers.

C7 Increase housing quality, affordability, stability, and proximity to resources.

C8 Improve air, water, and soil quality.

C9 Prevent violence using a public health framework.

C10 Provide arts and culture opportunities in the community.

Health Care Services Recommendations

HC1 Provide high-quality, affordable health coverage for all.

HC4 Take advantage of emerging technology to support patient care.

HC5 Provide health care resources in the heart of the community.

HC6 Promote a Medical Home model.

HC8 Ensure participation by patients and the community in health care related decision.

HC10 Provide outspoken support for environmental policy change and resources for prevention.

S1 Enhance leadership and strategy development to reduce inequities in health and safety outcomes.

S2 Enhance information about the problem and solutions at the state and local levels.

S3 Establish sustainable funding mechanisms to support community health and prevention.

S6 Expand community mapping and indicators.

02 Provide Federal Resources to support state and local community-based prevention strategies.

04 Improve access to quality education and improve educational outcomes.

Equitable Health:

A Four-Pronged Solution

In Alameda County, where we live and work, an African American child born today in Oakland’s flatlands will live an average of 15 years less than a White child born in the Oakland hills neighborhood.1 Further, for every $12,500 in income difference between families, people in the lower-income family can expect to die a year sooner. Tragically, public health data confirms this same jarring reality all across American cities, suburbs, and rural areas.

Good health is precious. It enables us to enjoy our lives and focus on what is important to us—our families, friends, and communities. It fosters productivity and learning, and it allows us to capitalize on opportunities. However, good health is not experienced evenly across society; heart disease, cancer, diabetes, stroke, injury, and violence occur in higher frequency, earlier, and with greater severity among low-income people and communities of color—especially African Americans, Native Americans, Native Hawaiians, certain Asian groups, and Latinos. (See Appendix A: Inequitable Rates of Morbidity and Mortality.)

Health inequity is related both to a legacy of overt discriminatory actions on the part of government and the larger society, as well as to present day practices and policies of public and private institutions that continue to perpetuate a system of diminished opportunity for certain populations. Poverty, racism, and lack of educational and economic opportunities are among the fundamental determinants of poor health, lack of safety, and health inequities, contributing to chronic stress and building upon one another to create a weathering effect, whereby health greatly reflects cumulative experience rather than chronological age.2 Further, continued exposure to racism and discrimination may in and of itself exert a great toll on both physical and mental health.3 Inequities in the distribution of a core set of health-protective resources also perpetuate patterns of poor health.

Historically, African Americans, Native Americans, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians, in particular, have to varying extents had their culture, traditions, and land forcibly taken from them. It is not a mere coincidence that these populations suffer from the most profound health disparities and shortened life expectancies. In many of the low-income and racially segregated places where health disparities abound, a collective sense of hopelessness is pervasive, and social isolation is rampant. This individual- and community-level despair fuels chronic stress, encourages short-term decision making, and increases the inclination towards immediate gratification, which may include tobacco use, substance abuse, poor diet, and physical inactivity.

To date, our collective national response has focused on what happens after people get sick or injured. Improving the health care system by increasing access and quality remains an integral component of addressing health inequities. At the same time, recent data indicates we must do more. Despite our decades-long investment in launching clinically focused initiatives to reduce health disparities, we have made virtually no significant progress in this domain in the United States.45

Health equity is everyone’s issue, and finding solutions will significantly benefit everyone. As the US population becomes increasingly diverse, achieving a healthy, productive nation will depend even more on keeping all Americans healthy. An equitable system can drastically lower the cost of health care for all, increase productivity, and reduce the spread of infectious diseases, thus improving everyone’s well-being. Last—and most importantly—the idea of equity is based on core American values of fairness and justice. Everyone deserves an equal opportunity to prosper and achieve his or her full potential, and it is our moral imperative to accomplish this.

We can remedy the problem of disparities in health and safety outcomes by creating a new paradigm addressing the needs that are critical to achieving health equity, and the specific challenges that affect integrating solutions into practice and policy. (See Appendix B: Definitions of Health Disparities and Health Inequities.) The first need is for a coherent, sustainable health care system that adequately meets the requirements of the entire US population and of racial and ethnic minorities in particular. The second need is for adequate community prevention strategies that target the factors underpinning why people get sick and injured in the first place. These should be integrated to form a unified system for achieving health, safety, and health equity in the US.

In this paper, we propose a set of solutions that are achievable within the local arena. By local, we mean state, regional, and community levels. These solutions not only address the critical needs but also bridge traditional health promotion, disease management, and health care solutions with more upstream work that focuses on preventing illness and injury in the first place. We will outline a composite of community and health care factors that affect health, safety, and mental health and that—most importantly—provide the framework for accomplishing our four-pronged solution:

- Strengthen communities where people live, work, play, socialize, and learn

- Enhance opportunities within underserved communities to access high-quality, culturally competent health care with an emphasis on community-oriented and preventive services

- Strengthen the infrastructure of our health system to reduce inequities and enhance the contributions from public health and health care systems

- Support local efforts through leadership, overarching policies, and through local, state, and national strategy

Policy and institutional practices are the key levers tor change. Institutional practices along with public and private policy helped create the inequitable conditions and outcomes confronting us today. Consequently, we need to focus on these areas—in community, business/labor, and government—in order to “unmake” inequitable neighborhood conditions and improve health and safety outcomes. Policies and organizational practices significantly influence the well-being of the community; they affect equitable distribution of its services; and they help shape norms, which, in turn, influence behavior.

POLICY PRINCIPLES

The following policy principles* provide guidance for taking on the challenge of addressing health inequities:

- Understanding and accounting for the historical forces that have left a legacy of racism and segregation is key to moving forward with the structural changes needed. A component of addressing these historical forces should consider policy and reform related to immigrant groups—notably Latinos, Asians, and Arab Americans.

- Acknowledging the cumulative impact of stressful experiences and environments is crucial. For some families, poverty lasts a lifetime and is perpetuated to next generations, leaving its family members with few opportunities to make healthful decisions.

- Meaningful public participation is needed with attention to outreach, follow-through, language, inclusion, and cultural understanding. Government and private funding agencies should actively support efforts to build resident capacity to engage.

- Because of the cumulative impact of multiple stressors, our overall approach should shift toward changing community conditions and away from blaming individuals or groups for their disadvantaged status.

- The social fabric of neighborhoods needs to be strengthened. Residents need to be connected and supported and feel that they hold power to improve the safety and well-being of their families. All residents need to have a sense of belonging, dignity, and hope.

- While low-income people and people of color face age-old survival issues, equity solutions can and should simultaneously respond to the global economy, climate change, and US foreign policy.

- The developmental needs and transitions of all age groups should be addressed. While infants, children, youth, adults, and elderly require age-appropriate strategies, the largest investments should be in early life because important foundations of adult health are laid in early childhood.

- Working across multiple sectors of government and society is key to making the necessary structural changes. Such work should be in partnership with community advocacy groups that continue to pursue a more equitable society.

- Measuring and monitoring the impact of social policy on health to ensure gains in equity is essential. This will include instituting systems to track governmental spending by neighborhood, and tracking changes in measurements of health equity over time and place to help identify the impact of adverse policies and practices.

- Groups that are the most impacted by inequities must have a voice in identifying policies that will make a difference as well as in holding government accountable for implementing these policies.

- Eliminating inequities is a huge opportunity to invest in community. Inequity among us is not acceptable, and we all stand to gain by eliminating it.

*ADAPTED FROM: Life and Death From Unnatural Causes: Health & Social Inequity in Alameda County. Alameda County Public Health Department September 2008

Critical Needs for Achieving Equitable Health in the United States: A Health System

We need a coherent, sustainable health care system that adequately meets the health requirements of the entire US population and of racial and ethnic minorities in particular

When we talk about fixing the health care system in the United States, we assume there is a system that can be improved. The underlying problem, however, is that we have no coherent system in the first place. While there are some elements in place, they are inaccessible to a vast number of people, especially the disenfranchised. The last time the World Health Organization published data on international health ranking in their World Health Report 2000—Health systems: Improving Performance, the United States ranked number one in health expenditure per capita but only ranked 37th in overall health system performance.6 Among industrialized countries, the United States came in 25th out of 30 on infant mortality and 23rd out of 30 on life expectancy.7 The fact that a growing number of people lack health insurance or adequate health insurance has been well documented.8 Furthermore, even for those with adequate access to health care, the system is flawed. For example, medical practitioners’ job dissatisfaction rates are growing, and major shortages in nursing and allied health professions are projected.9

America’s health care system is neither healthy, caring, nor a system.

WALTER CRONKITE

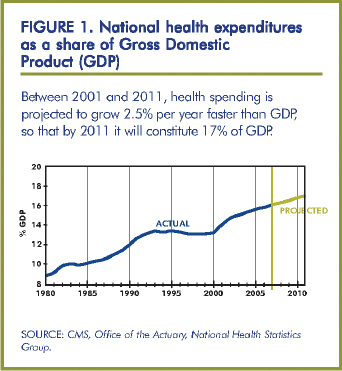

In a time of financial crisis, we may focus exclusively on reforming the areas of greatest expense in the economy, narrowing in on the cost of specific items as we try to reduce that cost or at least slow its increase. Studies have revealed that the dramatic rise in the prevalence of chronic disease is a major factor responsible for growth in US health care spending.10,11,12 This is a cost that can be reduced through prevention.13 (See Appendix C: The Economics of Prevention.) Further, our current health care system and its reimbursement structure are not designed to incentivize the necessary community-based prevention and management of chronic disease; thus the system is not meeting the needs of communities across our nation, and health care costs will continue to grow.

As we reform and redesign the health care system, we need to explicitly take the issue of equity into account, since anything done to reformulate how care is delivered can either mitigate or exacerbate the problem of inequity. Therefore, quality improvements to any health care component (e.g., prevention, access, and quality) have to embrace principles of cultural competency, diversity, and equity.

We need to create a coherent, comprehensive, and sustainable health care system that is culturally and linguistically appropriate, affordable, effective, and equally accessible to all people—especially disenfranchised populations. The overall health system should start with community strategies—reducing the likelihood that people will get sick or injured in the first place and helping to maintain the well-being of those who are already sick and injured. The overall system should also offer a full set of services (e.g., medical, dental, mental health, and vision), including screening, diagnostic, and disease management services, within the communities where people live.

We need adequate community prevention strategies that target the factors underpinning why people get sick and injured in the first place

Health care is vital but alone it is not enough. The health care system has great strength in its committed providers and in its ever-improving diagnosis, procedures, and medicines. Many formerly fatal diseases are now treatable and even curable. Yet, as important as it is to improve the quality of health care services, it is only part of the solution to improving health and reducing health inequities. Patterns of disease and injury that follow the socioeconomic status gradient would still remain.14 While health care is vital, there are three reasons why addressing access to and quality of health care services alone will not significantly reduce disparities: 1) Health care is not the primary determinant of health; 2) Health care treats one person at a time; 3) Health care intervention often comes late. (See Appendix D: Reasons why addressing access to and quality of health care alone will not significantly reduce inequities.)

If is unreasonable to assume that people will change their behavior easily when so many forces in the social, cultural and political environment conspire against such change.

INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE

In order to successfully address inequities in health and safety, we must pose the following questions: Why are people getting sick and injured in the first place? What impedes their ability to recuperate? Are their neighborhoods conducive to good health? What products are sold and promoted? Is it easy to get around safely? Is the air and water clean? Are there effective schools and work opportunities? Are there persistent stressors in the environment, and what is the long-term impact of this stress on health?

People’s health is strongly influenced by the overall life odds of the neighborhood where they live. Indeed, place matters. In many low-income urban and rural communities, whole populations are consigned to shortened, sicker lives. While residential segregation has declined overall since 1960, people of color are increasingly likely to live in high-poverty communities.15 Racially and economically segregated communities are more likely to have limited economic opportunities, a lack of healthy options for food and physical activity, increased presence of environmental hazards, substandard housing, lower performing schools, higher rates of crime and incarceration, and higher costs for common goods and services (the so-called “poverty tax”).16

Conversely, people are healthier when their environments are healthier. For example, in African American census tracts, fruit and vegetable consumption increases by 32% for each supermarket.17 When states moved to require infant car seats, the impact of policy far exceeded that of education in changing norms and thus behavior: usage for infants went from 25% maximum to nearly universal, and death and injury from car crashes decreased.18

Taking a step back from a specific disease or injury reveals the behavior (e.g., eating, physical activity, and violence) or exposure (e.g., stressors and air quality) that increases the likelihood of the injury or disease. Through an analysis of the factors contributing to medical conditions that cause people to seek care, researchers have identified a set of nine behaviors and exposures strongly linked to the major causes of death: tobacco, diet and activity patterns, alcohol, microbial agents, toxic agents, firearms, sexual behavior, motor vehicles, and inappropriate drug use.19 Limiting unhealthy exposures and behaviors enhances health and reduces the likelihood and severity of disease and injury. In fact, these behaviors and exposures are linked to multiple medical diagnoses, and addressing them can improve health broadly. If we take a second step back from the medical conditions, we see that specific elements of the environments in which people live are major determinants of our exposures and behaviors and thus of our illnesses and injuries. (For a more

in-depth understanding of this model, please go to Appendix E: A Health Equity Framework:—Taking Two Steps Back to the Determinants of Health.)

Therefore, improving the environments in which people live, work, play, socialize, and learn presents a tremendous opportunity to reduce health inequities by preventing illness and injury before their onset. THRIVE (Tool for Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments), a research- based framework created by Prevention Institute, offers a way to understand determinants of health at the community level.20 THRIVE includes a set of three interrelated clusters: equitable opportunity, people, and place. Within these clusters are highlighted key factors that influence health and safety outcomes directly via exposures (e.g., air, water, and soil quality; stressors such as racism) and/or indirectly via behaviors that in turn affect health and safety outcomes (e.g., the availability of healthy food affects nutrition). In addition, the environment also has an influence on people’s opportunity to access quality medical services, and these are included as a fourth cluster. On the following page, Table 1: Community Factors Affecting Health, Safety, and Mental Health, presents these four clusters.

Clearly, local solutions to health and safety inequities are central to success. Local work complements broader national change, and local solutions often help shape profound, long-lasting federal changes. Altering community conditions, particularly in low-income communities of color where the memory and legacy of dispossession remains, requires the consent and participation of a critical mass of community residents. Thus strategies that reconnect people to their culture, decrease racism, reduce chronic stress, and offer meaningful opportunities are ultimately health policies. Effective change is highly dependent upon relationships of trust between community members and local institutions. The process of inclusion and engaging communities in decision making is as important as the outcomes, which should directly meet the needs of the local population. Strategies such as democratizing health institutions, as was envisioned with the creation of community health centers, foster increased civic participation and serve as a health improvement strategy.

A quality health care system and community prevention are mutually supportive and constitute a health system

While health care and community prevention are often thought of as separate domains and operate independently, they actually are synergistic. Health care institutions have critical roles to play in ensuring an emphasis on health within communities as a key part of the solution. Health services must recognize that the community locale is an essential place for service provision, for example, by expanding community clinics, providing school health services, and giving immunizations in supermarkets. An effective health care institution will also provide broad preventive services, such as screening and disease management, that address populations at-risk and those that already have illnesses.

Health care also has a role to play in improving community environments. It is one of the nation’s largest industries and is often the largest employer in a low-income community. As such, health care institutions can support pipeline development to recruit, train, and hire people from the community, especially from underserved sectors. They can also advocate for community changes that will positively impact disease management, such as healthier eating and increased activity; improve the local economy by purchasing local products; create a farm-to-institution program to incorporate fresh, local produce and other foods into cafeteria or patient meals; reduce waste and close incinerators to reduce local pollution; and enhance staff and community access to fresh produce

TABLE 1. Community Factors Affecting Health, Safety, and Mental Health

EQUITABLE OPPORTUNITY

- Racial justice, characterized by policies and organizational practices that foster equitable opportunities and services for all; positive relations among people of different races and ethnic backgrounds

- Jobs & local ownership, characterized by local ownership of assets, including homes and businesses; access to investment opportunities, job availability, and the ability to make a living wage

- Education, characterized by high-quality and available education and literacy development across the lifespan

THE PEOPLE

- Social networks & trust, characterized by strong social ties among persons and positions, built upon mutual obligations; opportunities to exchange information; the ability to enforce standards and administer sanctions

- Community engagement & efficacy, characterized by local/indigenous leadership; involvement in community or social organizations; participation in the political process; willingness to intervene on behalf of the common good

- Norms/acceptable behaviors & attitudes, characterized by regularities in behavior with which people generally conform; standards of behavior that foster disapproval of deviance; the way in which the environment tells people what is okay and not okay

THE PLACE

- What’s sold & how it’s promoted, characterized by the availability and promotion of safe, healthy, affordable, culturally appropriate products and services (e.g., food, books and school supplies, sports equipment, arts and crafts supplies, and other recreational items); limited promotion and availability, or lack, of potentially harmful products and services (e.g., tobacco, firearms, alcohol, and other drugs)

- Look, feel & safety, characterized by a well-maintained, appealing, clean, and culturally relevant visual and auditory environment; actual and perceived safety

- Parks & open space, characterized by safe, clean, accessible parks; parks that appeal to interests and activities across the lifespan; green space; outdoor space that is accessible to the community; natural/open space that is preserved through the planning process

- Getting around, characterized by availability of safe, reliable, accessible and affordable methods for moving people around, including public transit, walking, and biking

- Housing, characterized by availability of safe, affordable, and available housing

- Air, water & soil, characterized by safe and non-toxic water, soil, indoor and outdoor air, and building materials

- Arts & culture, characterized by abundant opportunities within the community for cultural and artistic expression and participation and for cultural values to be expressed through the arts

HEALTH CARE SERVICES

- Preventive services, characterized by a strong system of primary, preventive health services that are responsive to community needs

- Cultural competence, characterized by patient-centered care that is understanding of and sensitive to different cultures, languages and needs

- Access, characterized by a comprehensive system of health coverage that is simple, affordable and available

- Treatment quality, disease management, in-patient services, and alternative medicine, characterized by effective, timely, and appropriate in-patient and out-patient care including for dental, mental health, and vision

- Emergency response, characterized by timely and appropriate responses in crisis situations that stabilize the situation and link those in need with appropriate follow-up care

by establishing accessible farmers’ markets or farm-stand programs. For example, Kaiser Permanente, the nation’s largest HMO, has instituted farmers’ markets in some of the communities it serves, providing healthy options tor the residents, offering a needed place to purchase quality food, and strengthening the nearby local farms.

Equally, community prevention efforts should be a part of the strategy to foster health and reduce health disparities by improving the success of treatment and injury/disease management even after people get sick or injured. Illnesses such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, HIV/AIDS, and cancer require patients to do what the medical practitioner requests, such as eat healthy foods and be more active. It is important for health care institutions to recognize the ways in which poverty and other social structures impede a patient’s ability to follow a doctor’s recommendations. Disenfranchised people usually don’t have safe places to walk or healthful food to eat. Overwhelmed with the requirements of work and daily life and coping with transportation and childcare issues, poor people can have more obstacles to keeping medical appointments as well. With community prevention efforts bolstering neighborhood environments and support structures, disease management strategies will be more effective.

Challenges to Achieving Health Equity through Practice & Policy

Achieving equitable outcomes is challenging and will take concerted attention, leadership, and investment. Building on interviews with local health officers conducted to inform the development of a Health Equity Toolkit funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as part of the project Advancing Public Health Αdvocacy to Eliminate Health Disparities, we have identified challenges that officials and communities face. This identification is key to shaping responsive solutions.

1. We haven’t embraced the problem of health inequities at its roots

We need to recognize that health inequities are rooted in historical policies and practices and are entrenched in social structures that create barriers to opportunity. This legacy remains invisible to many health care practitioners, policy makers, and the public. Practitioners and community spokespersons need to talk about race and social justice in new ways and often need guidance to do so effectively.

2. We don’t have a good playbook for how to do this

The people and institutions working tor reform need more guidance and information in order to identify and realize the most effective, sustainable changes. They often lack standardized, comparative data; documented examples of success; protocols tor adaptation, with attention to fidelity of core elements; a set of best practices; a framework to measure outcomes and successes; and clear goals tor the community.

The roles of different players are not well-defined. Many health issues can be traced to determinants that cross over into other public sectors, such as housing. Public health practitioners have indicated a need tor guidance on strategies where public health can take the lead.21 Further, they don’t always know how to coordinate with leadership in other sectors such as housing. In most

cases, the charge to address health equity will require public health practitioners to step outside of the contemporary bounds of public health, but this will mean establishing effective communication channels, navigating turf issues, and clarifying shared goals and objectives.

Also, the role of other institutions needs clarification as part of a coherent effort. Banks, businesses, multiple government sectors, schools, and community groups all have a major influence on health equity outcomes, even though they may not realize it or consider it in their decision-making processes. “While these players may not see themselves as having an active role, none should be taking actions that are detrimental to health outcomes.

3. A siloed system leads to a fragmented approach at best

Even if there were a shared understanding of the root of health inequities, sectors are siloed without a mechanism to work collaboratively to provide a coherent, effective set of solutions. By and large, there is a lack of coordination and cross-fertilization across sectors, efforts, and disciplines.22 This is critical to address, because reducing health inequities cannot be achieved by any one organization or sector, let alone any single department or division within public health.

Not only are sectors siloed, but the health system itself is siloed. Even within public health departments, opportunities to create meaningful collaboration across divisions, sections, or departments are limited. Categorical funding—important because it provides dedicated resources to deliver essential programs and services—can reinforce siloed approaches. There is even a divide between public health and health care; the two don’t work together systematically and strategically to catalyze, advocate for, and launch the kinds of solutions that can make a fundamental difference. Finally, community members are not consistently included in prioritizing problems or in shaping solutions.

4. Community-based, family-centered primary care is not a medical emphasis

Medical reimbursement, prestige, and medical education norms can all favor specialization over community-based, family-centered primary care. Furthermore, there is a lack of value and incentive placed on allied health professionals, promotoras (i.e., community health workers), and patient navigators. We also need to incentivize preventive services and better train medical providers in prevention.

5. Disparities in health care are not an organizational priority for many US hospitals

Many hospitals consider disparities in care as a function of conditions beyond their control. They may be reluctant to openly address “disparities” collaboratively, because this might be viewed as an admission of inequitable care.23 Often providers assume they administer equal care since it is their mission. Stratifying their publicly reported quality measures by patient race and ethnicity would be one way to confirm their assumption or identify areas for quality improvement work.

6. Health equity isn’t embedded in most people’s job descriptions; there are many competing demands

Research and practice in equitable outcomes tend to occur either as a small part of one’s job or as a specialty focus of a small group of experts within an organization. The challenge here is how to embed health equity into research and practice across and within organizations, bringing these efforts to scale, infusing them into the broader organizational culture, and propelling them to center stage.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Local Solutions for Advancing Equity in Health and Safety

Strengthen communities where people live, work, play, socialize, and learn

C1 Build the capacity of community members and organizations. Capacity building enables the residents and grassroots groups affected by poor health outcomes to better solve the community problems undermining health and safety. Strategies include:

- Train public sector staff to encourage local capacity building and to empower residents to take action in partnership with city and county governments and community-based organizations to improve their neighborhood conditions.

- Invest in both established and developing community organizations. Encourage and strengthen the capacity of these and other institutions and of individuals via financial support, technical assistance, and sharing best practices.

- Foster structured community planning and prioritization efforts to implement neighborhood- level strategies to address unfavorable social conditions.

C2 Instill health and safety considerations into land use and planning decisions. Land use, transportation, and community design (the built environment) influence health, including physical activity, nutrition, substance abuse, injuries, mental health, violence, and environmental quality. Strategies include:

- Ensure that health, safety, and health equity are accounted for in General Plans, Master Plans, or Specific Plans; zoning codes, development projects, and land-use policies.

- Engage community residents in developing zoning laws and general plans to integrate health and equity goals and criteria into community design efforts.

- Train public health and health care practitioners to understand land use and planning and to advocate for policies that support health and safety.

Integrating a community health and wellness element into general plans

The city of Richmond, California, is one of the first cities in the country to develop a comprehensive general plan element that addresses the link between public health and community design. Nearly 40% of Richmond’s residents live in poverty and over 60% are African American and Latino.24 This element addresses health impacts of community design decisions, such as zoning, on all Richmond residents as well as the historic impacts on low-income communities and communities of color, which share a disproportionately higher burden of negative health impacts. The General Plan considers factors such as physical activity, nutrition, non-motorized travelers’ safety, hazardous materials and contamination, air and water quality, housing quality, preventive medical care, homelessness, and violence, among others.

General plans are mandated for every city and county in California and typically cover a 20- to 30-year time period. Local authorities, either the Planning Commission and City Council for cities, or the Board of Supervisors for counties, must adopt a general plan. In practice, most local authorities appoint committees of residents to inform the process. In California, the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research outlines guidance for development of these plans, including the various elements that must be involved. Other states have similar requirements (and often refer to these plans as “Master Plans”). To date, elements directly addressing the health and justice implications of community design have never been included in the guidance but they are gaining attention.

C3 Improve safety and accessibility of public transportation, walking, and bicycling. Transportation is the means to accessing key destinations such as schools, workplaces, hospitals, and retail venues. Shifting the dominant mode of transportation from driving to greater public transportation use, walking and/or bicycling is a key step to increasing physical activity, reducing traffic injuries, and reducing developmental and respiratory illnesses from poor air quality. Strategies include:

- Implement land-use strategies such as high density, mixed-use zoning, transit-oriented development and interconnected streets that promote walking and bicycling as a means of transportation.

- Adopt complete streets policies in state and local transportation departments to ensure that roads are designed for the safety of all travelers including pedestrians, bicyclists, wheelchairs, and motor vehicles.

- Ensure that public transportation options are safe, easily accessible, reliable, and affordable.

- Design public transit routes to connect community residents to grocery stores, health care, and other essential services.

- Prioritize federal transit funding towards biking, walking, and public transportation.

New Jersey Safe Routes to School improvements in vulnerable communities

Safe Routes to School (SRTS) Federal funding gives states and localities a resource for programs that make walking and bicycling conditions safer, more accessible, and more convenient for children and their families. New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) is carrying out an Urban Demonstration Project in Newark, Trenton, and Camden to identify barriers to applying for and implementing SRTS programs in urban communities. NJDOT engaged students, school officials, and neighborhood partners to develop a needs assessment and a transportation plan that prioritized safe walking and bicycling. Through the community assessment process, NJDOT identified violence and crime, blighted buildings, and traffic safety as key concerns they will now address in the final package of infrastructure and programming improvements, using SRTS resources.

Congress created a $612 million federal SRTS program in the 2005 federal transportation bill to launch efforts from 2005 to 2009. The pending authorization of a new federal transportation bill can be an opportunity to substantially expand the SRTS program.

C4 Enhance opportunities for physical activity. Home, school, and community environments can either promote or inhibit physical activity. Physical activity is essential to preventing chronic illnesses and promoting physical and mental health. It is imperative to establish a foundation of activity behaviors from an early age and to provide environments with access to parks, open space, and recreational facilities that support people in attaining the daily recommended levels of physical activity.25 Strategies include:

- Develop and promote safe venues and programming for active recreation. Ensure parks, playgrounds, and playing fields are equitably distributed throughout the community.

- Facilitate after-hour (joint) use of school grounds and gyms to improve community access to physical activity facilities.

- Require recess and adopt physical education policies to ensure all students engage in develop- mentally appropriate moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on a daily basis.

- Establish state licensing and accreditation requirements/health codes and support implementation of minimum daily minutes of physical activity in after-school programs and childcare settings.

C5 Enhance availability of healthy products and reduce exposure to unhealthy products in underserved communities. The food retail environment of a neighborhood—the presence of grocery stores, small markets, street vendors, local restaurants, and farmers’ markets—plays a key role in determining access to healthy foods. Communities of color and low-wealth neighborhoods are most often affected by poor access to healthful foods.26 Research suggests that the scarcity of healthy foods makes it more difficult for residents of low-income neighborhoods to follow a good diet compared with people in wealthier communities.27 Strategies include:

- Invest in Fresh rood Financing Initiatives to provide grants, low-interest loans, training, and technical assistance to improve or establish grocery stores, small stores, and farmers’ markets in underserved areas.

- Encourage neighborhood stores to carry healthy products and reduce shelf space for unhealthy foods through local tax incentives, streamlined permitting, and zoning variances.

- Ensure grocery stores, small stores and farmers’ markets are equipped to accept Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (formally known as the Food Stamp Program) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) benefits.

- Establish and enforce regulations to restrict the number of liquor stores and their hours of operation.

Fresh food financing to enhance the availability of healthy products in underserved communities

In 2004, the Food Trust in Philadelphia, PA, in partnership with The Reinvestment Fund and the Greater Philadelphia Urban Affairs Coalition, identified a strong need for government investment to finance supermarkets, grocery stores, and other healthy food retailers in underserved communities. This led to the first statewide fresh food financing initiative. The Philadelphia Legislature allocated $10 million in its annual appropriations in 2004, with additional funds allocated in 2005 and 2006, to establish a grant and loan program to encourage supermarket development in underserved areas. The Reinvestment Fund leveraged the investment to create a $120 million initiative composed of state dollars, federal tax credit dollars, and private investments. To date, the initiative has provided $63.3 million in grants and loans for healthy retail projects, resulting in the creation of and improvements to 68 stores that offer fresh foods. These projects have generating 3,734 jobs and 1.44 million square feet of floor space.28 It is now seen as a model and is being replicated in other US communities.

For more information, visit: www.thefoodtrust.org/

C6 Support healthy food systems and the health and well-being of farmers and farm workers. What farms grow, how they grow it, and how it gets to the consumer have a profound impact on what we eat, on our health, and on our environment. US farm policy and agricultural research and education have contributed to the proliferation of industrial farms that grow grains, oil seeds, corn, meat, and poultry that serve as raw ingredients for cheap soda, fast food burgers, and other highly processed products. These industrial farms pollute the air, water, and soil while harming our nutritional health. Small- and mid-size farmers are struggling to make a living under the current system. Farmers of color face discrimination in access to loans. Farm workers are exposed to hazardous levels of pesticides,29 dangerous working conditions, and poor wages and living conditions. Strategies include:

- Support small- and mid-sized farmers, particularly farmers of color, immigrants, and women through grants, technical assistance, and help with land acquisition, marketing, and distribution.

- Establish incentives and resources for growers to produce healthy products, including fruits, vegetables, and foods produced without pesticides, hormones, or non-therapeutic antibiotics.

- Establish policies that support the health and well-being of farm workers, including enforcing occupational safety and health laws and regulations as well as banning pesticides that may pose health risks. Government entities can also facilitate wage increases for farm workers by providing grants and incentives for growers to engage in labor-sharing strategies with other growers.

Linking green renovation standards and health outcomes

The National Center for Healthy Housing in Columbia, Maryland, is using support from the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota Foundation to demonstrate how green building principles can improve health. The center is tracking the health impact of the green renovation of an affordable 60-unit apartment complex in Worthington, Minnesota. Residents are primarily low-income minority families employed in the food processing industry.

Results of this project can inform local zoning decisions and building codes. This is the first time the effect of green building principles will be measured against health outcomes over time. Early results include a majority of adults and children reporting improved health in just one year post-renovation. The adults made large, statistically significant improvements in general health, chronic bronchitis, hay fever, sinusitis, hypertension, and asthma. The children made great strides in general health, respiratory allergies, and ear infections. Overall, there were improvements in comfort, safety, and ease of housecleaning.

For more information, visit: www.nchh.org

C7 Increase housing quality, affordability, stability, and proximity to resources. High-quality, affordable, stable housing located close to resources leads to reduced exposure to toxins and stress, stronger relationships and willingness to act collectively among neighbors, greater economic security for families, and increased access to services (including health care) and resources (such as parks and supermarkets) that influence health. Strategies include:

- Support transit-oriented development and other policies and zoning practices that incentivize density, mixed-use, and mixed-income development.

- Ensure that housing standards; building permits for new buildings and rehabilitation; and housing inspections include safety and health considerations regarding design, the use of materials, and construction requirements.

- Protect affordable housing stock via rent control laws and condominium conversion policies, increase funding for emergency housing assistance, and maintain single room occupancy hotels.

- Support home ownership by creating community land trusts, increasing funds for and utilization of first-time home buyer programs, and establishing inclusionary zoning ordinances.

C8 Improve air, water, and soil quality. Environmental toxins present in air, water, soil, and building materials, including lead in soil and buildings, air pollution from motor vehicle traffic, and water pollutants, such as oil and human waste, have a substantial effect on health. Strategies include:

- Minimize diesel trucks in residential neighborhoods to reduce exposure to diesel particulates.

- Expand monitoring of air and water quality for impact on low-income and vulnerable populations.

- Enforce national water quality standards.

- Strengthen penalties for industrial and agricultural polluters.

- Replicate effective local lead abatement programs.

- Require public health input on air and water pollution impacts in local land use planning and development decisions.

Reducing toxic pollution in West Oakland

For two years, West Oakland residents and community partners worked to research and identify seventeen indicators to monitor environmental, health, and social conditions for their neighborhood. Residents then used the data in the indicators report to issue a formal request that the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD) develop stronger regulations requiring the Red Star Yeast factory (the area’s second leading source of toxic emissions) to reduce both pollution and noxious odors. The evidence in the report was also used to build media advocacy, testify at public hearings, and to garner letters demanding regulation and enforcement from the Department of Public Health and local elected officials. The combination of evidence and pressure led BAAQMD to remove the exemptions that had grandfathered Red Star Yeast into antiquated emissions standards.

For more information, visit: www.pacinst.org/reports/environmental_indicators/neighborhood_knowledge_for_change.pdf

C9 Prevent violence using a public health framework. Violence contributes to pre- mature morbidity and mortality and is a barrier to health-promoting activities, such as physical activity, and to economic development. Strategies include:

- Invest in citywide, cross-sector planning and implementation with an emphasis on coordinating services,30 programming, and capacity building in the most highly impacted neighborhoods, drawing on such tools as the UNITY RoadMap.*

- Support local intervention models to reduce the immediate threat of violence, such as the Chicago CeaseFire model.31

- Institute changes in clinical and organizational practices in health care settings to support and reinforce community efforts to prevent intimate partner violence, which results in injury and trauma from abuse, contributes to a number of chronic health problems,32 and disproportionately impacts immigrant women.33 (See Appendix F: The Role of Health Care Providers in Reducing IPV.)

______________

*The UNITY RoadMap is a resource for cities that maps out effective and sustainable solutions to prevent violence before it occurs. The UNITY RoadMap is informed by the findings from a literature review and interviews with violence prevention practitioners, vetted by city representatives and refined based on cities’ input. More information on both is available at: www.preventioninstitute.org/UNITY.html

Blueprint for Action: Preventing Youth Violence in Minneapolis

Recognizing that youth violence is a public health issue, the City of Minneapolis developed the Blueprint for Action: Preventing Youth Violence in Minneapolis. Using a comprehensive, holistic approach, the Blueprint aims to address the root causes of violence and significantly reduce and prevent youth violence using a combination of public health and law enforcement strategies. Under the leadership of Mayor JT Rybak, the Blueprint is the result of an 8-month collaborative process between the city and diverse community stakeholders. The four goals of the Blueprint are to:

- Connect every youth with a trusted adult;

- Intervene at the first sign that youth are at risk for violence;

- Restore youth who have gone down the wrong path; and

- Unlearn the culture of violence in the community.

Since the implementation of the Blueprint, juvenile-related violent crime citywide declined 37% since 2006 and 29% since 2007.34 In four of the five targeted neighborhoods, rates declined 43% in 2006 and 39% since 2007.35 Additionally, the City of Minneapolis has provided over twelve community organizations with grants to support youth employment, academic enrichment, and other community-based programs. Currently, the city has developed a youth violence prevention legislative agenda, which calls for a statewide policy that defines youth violence as a public health issue. It is a member of the UNITY City Network, a public health initiative funded by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For more information, please see: www.ci.minneapolis.mn.us/dhfs/yv.asp for Blueprint for Action: Preventing Youth Violence in Minneapolis and http://preventioninstitute.org/UNITY.html for UNITY: Urban Networks to Increase Thriving Youth.

C10 Provide arts and culture opportunities in the community. Artistic and cultural institutions have been linked with lower delinquency and truancy rates in several urban communities,36 and participation in the arts has been associated with academic achievement, election to class office, school attendance,37 appropriate expression of anger, effective communication, increased ability to work on tasks, less engagement in delinquent behavior, fewer court referrals, improved attitudes and self-esteem, greater self-efficacy, and greater resistance to peer pressure.38 Strategies include:

- Support community art centers and other opportunities for creativity in the community.

- Integrate art and creative opportunities into existing programs and businesses.

- House art commissions within state or city government.

- Work with large art institutions, local policy makers, and residents to bring “Big Art” (e.g., museums and orchestras) to low- and middle-income communities.

- Implement a policy to receive a portion of every ticket sold in the community for movies, sporting events, etc. as an alternate source of funding for arts and culture. Another funding mechanism involves redirecting a portion of hotel and car rental taxes, since art contributes to enhancing the community.

Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Project

The Mural Arts Project (MAP) in Philadelphia has created 2,500 murals citywide. These murals have transformed otherwise depressed and blight-filled neighborhoods throughout Philadelphia into public art displays that cultivate neighborhood pride and reflect the culture, history, and vision of the communities in which they were created.

MAP is an offshoot of the Anti-Graffiti Network, an already existing program intended to provide alternatives to young people engaged in graffiti and other crime. Launched by former Philadelphia Mayor Wilson Goode in 1984, MAP became institutionalized within the city’s Department of Recreation more than ten years ago, and in this role it has created new partnerships among government agencies, educational institutions, corporations, and philanthropic foundations to bring murals to fruition. This program trains thousands of youth every year and provides them with the skills to contribute to the aesthetic of their own neighborhoods. It offers an alternative to gangs and a place to receive mentorship from working artists. More recently, in addition to working with youth, The Mural Arts Program began offering a wide array of mural-making programs for adult men and women at correctional facilities in Pennsylvania’s State Correctional Institution (SCI) and several sites within the Philadelphia Prison System.

In 1971, Seattle, Washington, established an Arts Commission by ordinance and issued a subsequent ordinance requiring all infrastructure projects to set aside 1% of their project costs for public art. Seattle is a national leader in providing residents and visitors with experiences in public art.

Enhance opportunities within underserved communities to access high-quality; culturally competent health care with an emphasis on community-oriented and preventive services

HC1 Provide high-quality, affordable health coverage for all. Everyone, including the most vulnerable populations, should have equal access to health care, including medical, dental, vision, and mental health services. There are a disproportionate number of racial and ethnic minorities who either do not have any health insurance or are enrolled in “lower-end” health plans.39 Strategies include:

- Equalize access to high-quality health plans to limit fragmentation of health care services. For example, Medicaid beneficiaries should be able to access the same health services as privately insured patients.40

- Ensure that all eligible children and families enroll in and access the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP).

- Support safety net hospitals through state insurance coverage and state and local subsidies.41

- Ensure equitable support for dental and mental health services.

- Improve access through equitable and fair sharing of health care costs; streamline public health insurance enrollment and increase affordability of services within existing public programs, such as Medicaid; evaluate outreach to and enrollment of underserved populations; and support state and local legislative proposals for universal access to quality health care.

Health care coverage in Massachusetts42

Massachusetts’s Chapter 58 of the Acts of 2006 provides near-universal health insurance coverage and aims to ensure that all state residents have health insurance options that provide “minimal creditable coverage.” The law also has several key provisions that directly and indirectly address disparities in health care. Provisions include:

- Subsidizing health premiums for residents whose incomes fall below 300% of the Federal Poverty Level;

- Charging a new state entity, the Connector, to negotiate with health plans to increase the affordability of unsubsidized coverage and maximize the enrollment of low-income uninsured residents;

- Promoting the diversity and cultural and linguistic competence of health care professionals by establishing a Health Disparities Council in the Office of Minority Health;

Strengthening the data collection and monitoring of disparities through a Health Care Quality and Cost Council within the State Office of Health and Human Services charged with reducing racial and ethnic health disparities and publicly reporting disparities data.

HC2 Institute culturally and linguistically appropriate screening, counseling, and health care treatment. Culture shapes beliefs, behavior, and expectations surrounding health and health care. Physicians and other health care providers should deliver quality services in a culturally competent and sensitive manner. This approach can increase patient satisfaction, patient adherence to treatment plans, and the probability of improved health outcomes. Strategies include:

- Adopt standards of practice that are sensitive to the language and cultural needs of all patients.

- Provide training for providers to conduct screening, counseling, and treatment in both a culturally appropriate and sensitive manner.

- Promote culturally and linguistically appropriate screening programs for specific populations, such as Asian women for cervical cancer and other targeted groups for breast and cervical cancer.

- Ensure an effective communication strategy that takes into account the patients health literacy and preferred language.

- Ensure patient-system concordance (i.e., a setting of care delivery that optimizes patient adherence and a sense of security and safety).

California’s Health Care Language Assistance Act43

The first of its kind in the country, SB853 holds health plans accountable for the provision of linguistically appropriate services and requires the California Department of Managed Health Care to develop standards for interpreter services, translation of materials, and the collection of race, ethnicity, and language data. The bill was sponsored by the California Pan Ethnic Health Network. The law went into full effect on January 1, 2009.

Summary of SB 853 and its regulations:

- Health plans must conduct a needs assessment to calculate threshold languages and collect race, ethnicity, and language data of their enrol lees.

- Health plans must provide quality, accessible, and timely access to interpreters at all points of contact and at no cost to the enrol lee.

- Health plans must translate vital documents into threshold languages.

- Health plans must ensure interpreters are trained and competent and that translated materials are of high quality.

- Health plans must notify their enrollees of the availability of no cost interpreter and translation services.

- Health plans must train staff on language access policies and procedures and on working with interpreters and limited English proficiency patients.

Non-traditional approaches to improving immigrant mental health and social adjustment

This concerns how well both immigrants and their receiving communities are able to draw on their strengths and overcome the challenges affecting the health and vitality of entire communities. Recognizing that social capital/connectedness is a determinant of health, the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota Foundation created Healthy Together: Creating Community with New Americans, a statewide grantmaking initiative to reduce health disparities for immigrants and refugees, supporting more than 140 projects since 2005. This effort can serve as a model for institutions and governments across the nation. Some promising strategies include:

- Helping new immigrants forge social connections and rebuild the sense of community they may have lost by connecting them to others facing similar issues and creating social gatherings through “Talking Circles.”

- Providing information and education and pursuing other means to “normalize” and remove stigma and misconceptions from mental health issues and treatment.

- Building on client’s strengths, helping them to reframe their experiences as survivors rather than as victims and to create their own solutions.

- Building cultural competence of providers to recognize mind/body connections and focus on symptoms. The report is available online at www.bcbsmnfoundation.org

HC3 Monitor health care models/procedures that are effective in reducing inequities in health and data documenting racial and ethnic differences in care outcomes. Detailed documentation of health care models/procedures will delineate the key elements of success. Currently, hospital practices for data collection vary widely as do the racial and ethnic classifications used. Strategies include:

- Standardize data: Collect race and ethnicity data in all health institutions. Coordinate state standards for data collection on race and ethnicity with federal standards to track the health of minorities.44 Although it may be difficult to use data to compare institution-to-institution, hospitals can use it to identify existing disparities in care and track trends for different patient populations within a hospital.

- Coordinate data collection and data systems beyond individual institutions and the health care system: Multiple partners from various sectors should be involved in outreach to different populations. For example, when addressing asthma management, school systems would be able to reach out to a broad range of school-aged children. Public health can play a key role in coordinating data collection at the community level and comparing it across systems.

- Disaggregate the data: Ensure that data reflects differences within the broad categories of race and ethnicity (particularly among Latino and Asian/Pacific Islander populations), as well as income levels, and duration of residence in the United States. Adopt uniform patient classifications in health information technology to make quality analysis easier and quicker. Analysis should be included in quality improvement initiatives.

- Incorporate new accreditation standards and mandates that account for equitable health care.

- Apply emerging data practices to better determine what medical procedures are most effective for different populations. (One size does not necessarily fit all.) Explore the Expecting Success disparities collaborative as one such example. Upon submission of their LOI, although the majority (97%) of the 122 hospitals were collecting patient race and ethnicity data, almost none reported using the data for quality improvement purposes at that time. Currently, they are among the most likely to have begun using quality data to reduce inequities in care.45

HC4 Take advantage of emerging technology to support patient care. Recent advances in health care technology can strengthen medical treatment. To the extent that technology is used as an element of quality medical care, it’s important to ensure that these advances fully benefit everyone. Cell phones are one area where there is a high degree of market penetration among all groups and so we should capture their potential to support medical treatment so as not to exacerbate disparities. When technology is not equally available (e.g., computers in every home), alternatives should be provided that are efficacious. Strategies include:

- Institute electronic health records that protect privacy but ensure caregivers have all needed information.

- Use telephone and email reminders to increase frequency of appointments and testing compliance, reduce failure to take pills, and encourage following procedures.

- Make tailored health information easily accessible and responsive.

Automated Telephone Self-Management Support System (ATSM)46

The Improving Diabetes Efforts across Language and Literacy (IDEALL) Project, run out of the California Diabetes Prevention and Control Program, is successfully utilizing health information technology as an efficient patient-centered approach to diabetes management for underserved populations with communication barriers such as limited literacy and limited English proficiency.47

IDEALL compared the effectiveness of two diabetes self-management support interventions (ATSM system and group medical visit support system) against the standard diabetes management approach. More than half of the participants had limited English proficiency, more than half had limited literacy, and half were uninsured. Participants in the ATSM group had the highest levels of participation and showed better communication with providers as compared to usual care and group medical visits. The ATSM participants also demonstrated significant increases in physical activity, exhibited the greatest improvements in carrying out daily activities, and spent fewer days in bed due to illness. Tailored to individual language and literacy need, the ATSM is a cost-effective intervention with great potential for underserved diabetes patients with low literacy and English proficiency levels.48

For more information, contact Dean Schil linger, MD, dschillinger@medsfgh.ucsf.edu

HC5 Provide health care resources in the heart of the community. Strengthening the presence of health care services located in communities of high need reinforces the connection between health care and community and can remove pervasive access barriers such as inadequate transportation options or not being able to seek health care during traditional working hours. Strategies include:

- Support community-based clinics. Clinics have an essential role in improving community health and providing services for uninsured and underserved populations. Clinics should establish organizational practices to increase access to equitable health care.

- Expand availability of school-based health clinics.

- Provide support groups that enhance self-efficacy in engaging in healthy behaviors.

- Provide culturally appropriate care such as translation services, disease prevention counseling, advocacy for quality health care, and other services to patients directly in the community, not just in health care settings.

- Expand the use of community health workers. Reforming reimbursement is essential, including state grants and seed funding as resources.49

- Change the available work hours and locations to meet the needs of patients.

Project Brotherhood in Chicago, Illinois

Supported by seed money from the Cook County Hospital, Project Brotherhood opened its doors as a health and human services provider to African American men in Chicago in 1998. With support from the Cook County Bureau of Health Services Health Center, Project Brotherhood provides services for men on a drop-in basis. Its explicit mission is to address the physical and mental health needs of a neglected population of Black men in a culturally relevant manner. There is no need for an appointment for physicals or lab tests, which are often needed in order to gain employment. Both primary and specialty health care are provided for free, allowing the low-income men that Project Brotherhood primarily serves to access high-quality, culturally appropriate health care that has historically been inaccessible. To increase levels of initial trust, the majority of staff is both African American and male, services are delivered in a less formal environment by offering weekly casual evenings where doctors, staff, and clients participate in informal support group discussions, and a barber provides free haircuts and counseling.

Project Brotherhood continues to grow the number of patients it is reaching with its services:50

- In 1999, Project Brotherhood averaged 4 medical visits and 8 group participants a week.

- By 2005, they averaged 27 medical visits and 35 group participants a week—and 14 haircuts per clinic session.

- No show rates of Project Brotherhood medical visits average 30% per clinic session compared to 41 % at the main health clinic.

- By 2007, Project Brotherhood provided services to more than 13,000 Black men.

On Lok Senior Health Services

With support from the City of San Francisco, in 1983, On Lok Senior Health Services obtained waivers from Medicare and Medicaid to test a new financing method for long-term care. In exchange for fixed monthly payments from Medicare and Medicaid for each enrollee, On Lok was responsible for delivering the full range of healthcare services. This model served as a prototype for a national initiative passed in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997—the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), which receives funding from both Medicare and Medicaid and provides an alternative to the traditional nursing home model for elder care. As a certified PACE program, On Lok seniors who are both Medicare and Medi-Cal (Medicaid in California) beneficiaries receive comprehensive health and health-related services with no premiums or co-payments. Supplemental Security Income Program (SSI) benefits can also be contributed to the cost of On Lok services. For seniors who are only Medicare beneficiaries, the cost of services not covered by Medicare are paid for out-of-pocket and are determined by personal income and assets. Its main goal is to keep seniors at home living in their communities for as long as possible. On Lok’s services encompass full medical care, prescription drugs, home care, adult day health, transportation, and more. On Lok, means “peaceful, happy home” in Cantonese, the language spoken by most of its elderly participants. Although it is rooted in Chinese cultural traditions of reverence for elders, the program long ago branched out to serve other ethnic and racial groups.51 In expanding its services to various neighborhoods, a paramount consideration is the culture of the community it is serving.

HC6 Promote a medical home model. Having a designated health provider for every patient and, ideally, every family has enormous benefits. Primary care becomes more accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family-centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective. Patient-centered care is given within a community and cultural context. In 2007, the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, and American Osteopathic Association released the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Far fewer people of color have a medical home, which is strongly associated with prevention, screening, and specialty care referral.52 Strategies include:

- Design interventions to incorporate detection, prevention, and management of chronic disease with full deployment of multi- disciplinary teams that are family and patient centered.

HC7 Strengthen the diversity of the health care workforce to ensure that it is reflective and inclusive of the communities it is serving. The diversity of health care professionals is associated with increased access to and satisfaction of care among patients of color. States can adopt strategies such as loan repayment programs and service grants, health profession pipeline programs, and other incentives for service.53 Strategies include:

- Train clinic providers to conduct culturally appropriate outreach and services.

- Address the imbalance of health care providers by offering incentives to work in underserved communities.54 States could provide incentives that include funding graduate medical programs focusing on underserved populations, tuition reimbursement, and loan forgiveness programs that require service in Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs).

- Expand use of Community Health Workers (CHWs) as a means of diversification. By acting as health connectors for populations that have traditionally lacked access to adequate health care, CHWs meet the ever-changing health needs of a growing and diverse population. Their unique ties to the communities where they work allow CHWs to understand cultural and linguistic needs and provide a resource for populations that are not necessarily connected or trusting of the medical system.

Invest in community health workers

The State of Kentucky dedicates $2 million annually for Kentucky Homeplace, an initiative that relies substantially on approximately 40 trained Community Health Workers (CHWs)* to deliver services to rural, underserved populations in 58 counties. Similarly, the City of Fort Worth, Texas, has permanently budgeted for 12 community health worker positions within their Department of Public Health. These particular CHWs are based in neighborhood police stations and work on teams with nurses and social workers responding to non-urgent health and social issues from the community at large. The City also supports the CHWs with training and with addressing issues of health disparities.

For nearly a decade, the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota Foundation has served as a catalyst to promote the training and use of CHWs. The foundation’s support has led to:

- Sustainable financing—Minnesota is the only state, other than Alaska, to obtain Medicaid reimbursement for CHW services.

- An 11 -credit CHW certificate program based in the community college system.

- Peer learning and professional development through the Minnesota CHW Peer Network.

- A workforce development partnership through the Minnesota CHW Policy Council.

- Awareness building through a public television program and accompanying DVD.

- CHW models with a current focus on mental health.

- Health plan uptake at Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota through a CHW internship.

For further information on certain CHW services, visit www.mnchwinstitute.org/MN_Legislation.asp

* CHWs are also known as Lay Health Workers, Promotoras de Salud, Outreach Workers, or Community Health Advocates.

HC8 Ensure participation by patients and the community in health care related decisions. Research suggests that the consistency and stability of the relationship between patient and doctor is an important determinant of patient satisfaction and access to care. However, people of color are less likely to have a consistent relationship with a provider, even when insured at the same levels as White patients.55 Strategies include:

- Develop and strengthen patient education programs to help patients navigate the health care system.56

- Promote community health planning, which actively involves community residents in planning, evaluation, and implementation of health care efforts.57

Senior Injury Prevention Partnership (SIPP)

The population over age 60 will more than double nationally in the next 20 years. In 2005, people age 65 and older represented a little more than 10% of the population of Alameda County but accounted for more than 45% of all hospitalizations and deaths due to unintentional injury.58 Traditionally, injury prevention programs have focused primarily on children. The Senior Injury Prevention Partnership (SIPP), formed more than 10 years ago by the Alameda County Public Health Department and a diverse array of partner organizations, addresses the needs of the older population in our county. SIPP promotes a muIti-factoriaI fall-prevention program that includes: physical activity, home safety, education, and medication management. SIPP got its start with state and foundation grant funding. Following its initial success and advocacy by seniors, local government funding was also allocated. SIPP trains clinicians working with adults age 65 and over. Their program goes beyond the typical boundaries of the traditional medical model by putting peerled physical activity programs into place, which have proven to be as or more effective than programs led by clinicians.59 SIPP is currently hosting trainings for physical activity “lay leaders”—who are often older adults themselves—at senior centers, residential facilities, and other independent senior living locations. By bringing physical activity programs to seniors (rather than the other way around), SIPP increases the likelihood of participation and helps make the healthy choice the easy choice.

HC9 Enhance quality of care by improving availability and affordability of critical prevention services. Access to culturally competent, accessible clinical preventative services is a key ingredient to keeping people healthy. Examples include:

- Immunizations of children, adults and seniors.

- Regular monitoring of children’s growth.

- Assessment of prevention and safety behaviors (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, gun use; vehicle safety devices; family violence; risks including guns, STD’s).

- Medical testing and screening.

- Patient education, counseling, and referrals (e.g., smoking cessation, dietary counseling, and physical activity programs).

- Oral health, a key element of medical care that is too often overlooked.

A community-driven project to reduce STDs in Minneapolis60