“Murder and mayhem and whatnot is much more exciting than test tubes and Erlenmeyer flasks.”

–Paul Bryan

Speakers in this session discussed chemistry in different types of science museums, which have served as popular venues for informal learning for many years.1 The speakers included Sapna Batish from the National Academies’ Marion Koshland Science Museum, in Washington, D.C.; Susanne Rehn, via webcast, from the Deutsches Museum, in Berlin, Germany; Shelley Geehr from the Chemical Heritage Foundation, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Peter Yancone from the Maryland Science Center, in Baltimore, Maryland.

CHEMISTRY AT THE KOSHLAND SCIENCE MUSEUM

Sapna Batish provided a brief history of the National Academies’ Marion Koshland Science Museum (Figure 5-1). The Koshland opened in April 2004 and prides itself on being a science museum for teens, unlike many museums in the United States that are focused on an elementary school audience. All of the Koshland exhibit content is based on studies conducted by the National Research Council (NRC). An exhibit topic is chosen based on there being a major body of work by the NRC to support it, if it is continuing to be researched, and if it has significant relevance to society.

The Koshland is considered a hands-on museum. Rather than having artifacts, the museum focuses on using digital interactive equipment to convey science to its audience (Figure 5-2). The museum is also unique in that it shows the confluence of science and policy, given that its exhibits are based on NRC studies about scientific topics that are relevant to society. In addition to having a general audience, the museum also works with middle school and high school students. It offers free field trips and transportation to middle school and high school students in the Washington, D.C., area. Batish added, “We like to connect current science with tangible, real-life scenarios for students and teachers. All materials have been designed by former teachers and are field-tested with students.”

FIGURE 5-1 Marion Koshland Museum, located at the corner of 6th and E Streets, N.W., Washington, D.C.

SOURCE: Marion Koshland Museum, 2010.

Koshland has three main exhibits. The first is called the Wonders of Science, which includes satellite imagery, population density, and energy use over a 10-year period, as well as the human cell. There is also an exhibit developed at Harvard Medical School featured in the museum, as well as an interactive exhibition that looks at the origins and expansions of the earth and the universe.

The second exhibit looks at emerging challenges of infectious diseases, such as malaria, AIDS, and tuberculosis, in an interactive manner. Batish explained, “In the one on tuberculosis, visitors get to be doctors. They get to choose a patient,

__________

1For an excellent historical look at science museums, see A.J. Friedman. 2010. The evolution of the science museum. Physics Today (October): 45-51.

FIGURE 5-2 The Koshland museum focuses on using digital interactive equipment to convey science to its audience.

SOURCE: Marion Koshland Museum, 2010.

and then they administer medication to the patient over the course of 18 months, and they get to see what the viral load looks like, and they get to understand why it is that this issue is prevalent and a problem in different parts of the world.”

The last of the three exhibits is on global warming. It has been there since the museum opened and displays evidence that humans are causing recent climate change. She added, “It starts off by asking, Has the climate changed, what are its causes, how might it change in the future, what are the consequences, and how can science be used to inform our responses to climate change?”

Chemistry is offered through all core areas of the Koshland, which include museum exhibits, field trips, hands-on science in the museum, community outreach efforts, public programs, and its website. As she heard many of the speakers say, Batish added, “Chemistry is just an inherent part of every aspect of life. We don’t have to talk about chemistry from the perspective of an atom or a molecule at the museum. It becomes apparent to visitors that the basic fundamentals of what we are talking about are based on chemistry.”

For example, there is an exhibit that shows images of ice cores. It helps visitors understand how ice cores can be used to measure the temperature of the earth 500,000 to 800,000 years ago. It involves using a ratio of oxygen isotopes from air bubbles trapped in the ice cores to infer temperature. “Then, coming back to the present, we talk about changing concentration of greenhouse gases and what that means in terms of our current and future climate,” Batish added.

One of the most popular exhibits is one that focuses on decision making. The Koshland found that visitors really enjoy this exhibit because they get to consider the environmental and economic trade-offs of decisions. For example, there is one scenario in which visitors see the impact on reducing greenhouse gases when they choose between planting trees and increasing building efficiency (Figure 5-3). They get to consider the economic and environmental trade-offs of each of the options.

Based on the success of that exhibit, the museum is in the process of developing a new climate gallery. It is going to be based on two recent NRC studies—America’s Energy Future and America’s Climate Choices. The climate gallery will include topics such as climate science, climate impacts, mitigation, and adaptation to climate change. They will be much more focused on decision making and on advanced decision-making tools.

Batish noted that it is challenging to help the public understand something as vague and ambiguous as climate change through a hands-on science activity. She said that the

FIGURE 5-3 Consider the alternatives. Koshland Science Museum visitors make a choice between planting trees and increasing building efficiency to reducing greenhouse gases.

SOURCE: Marian Koshland Museum, 2010.

museum has been fortunate to have science and technology policy fellows (recent Ph.D. scientists) helping to develop these hands-on activities. One activity was developed by a chemistry student who was finishing up her Ph.D. in chemistry at Northwestern. It shows museum visitors how changing chemistry levels can lead to ocean acidification. The activity also helps visitors understand how ocean acidification will impact calcareous plankton, coral reefs, and other marine ecosystems.

The museum is involved in many festivals around the city. One in particular is the Arts on Foot Festival. It takes place near the Verizon Center every September. Batish showed a picture of one of the fellows engaging in an exercise that simulates the spread of infectious disease, using simple ingredients to represent bacteria, vaccines, and antibiotics. “We help them to understand how quickly disease can spread and what we can do to combat that,” she explained.

The Koshland also offers public programs. Batish showed a picture of a family at a Saturday program learning about the importance of Vitamin C. It is vital for human health, and humans cannot produce it so it must be acquired it though diet. During the program, visitors test different sports drinks to determine the levels of Vitamin C. Another activity highlighted the importance of iron in fortified breakfast cereals—in its elementary form, not in combination with any other compounds. She said museum visitors were able to actually extract iron from a slurry of breakfast cereal flakes in a Ziploc bag using a strong magnet.

Finally, Batish noted that there are DVD ROMs and interactive exhibits on the Koshland website that help people understand the importance of chemistry and its relevance in today’s society. One example is Safe Drinking Water Is Essential. It is a virtual (online) exhibition on safe drinking water. She said that the online exhibition attracts domestic as well as international audiences. It also attracts decision makers, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and educators and is available in five languages. “What we really want people to understand is, it demonstrates the evidence for the growing populations without access to adequate drinking water. It gives survey solutions and technologies to increase the quality and quantity of drinkable water in the world,” Batish concluded.

CHEMISTRY AT THE DEUTSCHES MUSEUM

The next speaker provided insights from a museum known internationally for its exemplary chemistry and chemical engineering exhibits, the Deutsches Museum (Figure 5-4). Susanne Rehn explained that the museum is the largest science and technology museum in Germany, with approximately 1.4 million visitors annually. It was founded by Oskar von Miller in 1903. She mentioned that since the beginning of the exhibitions, there has always been a chemistry department.

FIGURE 5-4 The Deutsches Museum, which opened its doors on the Museum Island in 1925, is the largest science and technology museum in Germany, with approximately 1.4 million visitors annually. The chemistry galleries with approximately 1,000 square meters have been closed for redesign since 2009.

SOURCE Susanne Rehn; copyright: Deutsches Museum.

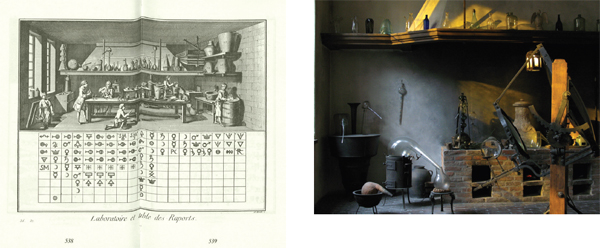

The original chemistry exhibition was divided into two sections, one historical and one focused on modern applications of chemistry. In parallel there were exhibitions of chemical engineering. She said chemistry now occupies about 1,000 square meters, roughly 10,700 square feet, on the first floor of the museum building. However, the museum’s chemistry exhibition has been closed to the public since autumn 2009. It will be completely redesigned, with an expected opening in 2012. The three historical laboratories, replicas of the alchemy laboratory, Lavoisier’s laboratory (Figure 5-5), and Liebig’s laboratory, are very popular and will continue to be a part of the renovated exhibition.

Rehn said, “The laboratories were designed according to historical models, putting visitors into the appropriate time. Essentially the visitors become part of a life-sized stage. The stage shows and explains basic methods and insights gained during the time, but individual objects, chemistry explanations, and persons take a back seat.” The alchemy laboratory represents a typical post-medieval laboratory based on paintings of David Teniers the Younger.2 From the beginning, she said, the laboratory replicas were meant to show the abundance and variety of equipment and materials used in the past. Over the decades, they have had to reduce the diversity, and install a railing and an alarm system.

Rehn then talked about the old exhibition of scientific chemistry. Visitors entered the exhibit after the historical laboratories. It featured a high standard with regard to con-

__________

2To view historic artwork depicting alchemy, see the Chemical Heritage Foundation website at www.chemheritage.org/discover/collections/search.aspx?collectiontype=FineArt&q=alchemy (accessed November 29, 2010).

FIGURE 5-5 The chemistry galleries in the Deutsches Museum are famous for their life-size reconstruction of historical chemical laboratories. A typical laboratory of the eighteenth century was built after an illustration found in Diderot’s Encyclopedia (left). Being the same period in which the great chemist Antoine Laurent Lavoisier lived, the laboratory is called “Lavoisier’s laboratory” (right). Other historical laboratories in the museum show chemistry in medieval times and in the nineteenth century.

SOURCE: Susanne Rehn; copyright: Deutsches Museum.

tent. There were different chemical reactions set up behind glass that could be performed with the push of a button. The reactions demonstrated chemical foundations, such as acid-base reactions, coordination complex reactions, redox reactions, and so on. However, no connection was made between the reactions and the daily lives of visitors. The design was also quite monotonous, with long corridors that left the public uninspired and unengaged in the information, according to Rehn.

The exhibition did contain occasional historical objects. For example, it included the famous table showing the original instrument used by Otto Hahn and Lisa Meitner when they discovered nuclear fission. In contrast to the historical laboratories, the objects found near the chemical reactions were described in detail.

Rehn explained that the previous exhibition had some great merit because it focused on chemical experiments. Visitors were able to conduct a large number of experiments, which they enjoyed. The experimental equipment was simple, but it was not visible to the visitor, which made it difficult to understand the science going on. Also the glass window between the experiment and the visitor created a distance that kept people from reading the text and understanding what happened.

The third feature of the chemistry exhibition, even more popular than the historical laboratories and chemistry experiments, was the experimental lecture. The lectures took place up to three times a day and attracted an audience of about 14,000 during the last year the exhibition was still open.

Rehn said, “One can speculate about the reasons for this popularity. One reason may be that the [lecture] experiments shown resulted in spectacular displays. Another may be that the background to each reaction was explained on the spot by the colleagues holding the lectures. Personally, I believe that a significant reason can be found in the lack of distance. No glass between the visitors and the experiments, no long texts to read, and so on.” In approaching the redesign of the chemistry exhibition, the museum had as its goal to expand upon the basic approach of turning chemistry into an experience. It wants to show that chemistry is an innovative, responsible science. “I don’t know how this is seen in the United States, but in Germany there is considerable prejudice against chemistry, regardless of any achievements of the past. Chemistry may be any of these: unnatural, toxic, harmful. On top of this, chemistry only happens in laboratories far, far away. Our goal is to break up this rigid image and consciously highlight chemistry where visitors meet it every day,” explained Rehn.

“One of our most important messages is that chemistry has benefits for every one of us in the whole society,” Rehn said, so the selected topics include sports, fashion, leisure, and so forth, which explain plastics and advanced materials. Other topics include nutrition, cosmetics, construction, and energy stores. A section called analytics will feature forensics. “We are designing a virtual crime scene, and visitors will be able to find out more about the scientific background of analyzing each piece of evidence. This way, we lead the visitors through analytical principles like paper

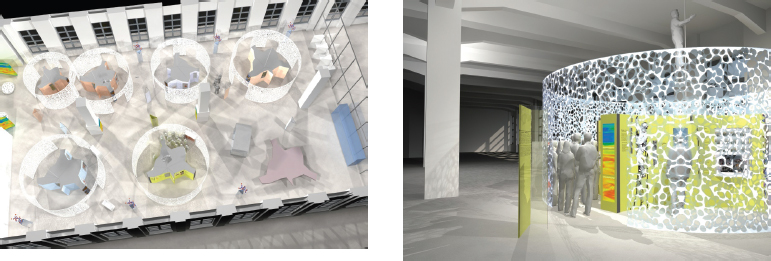

FIGURE 5-6 The complete redesign of the chemistry exhibition. The approach is to turn chemistry into an experience. The museum wants to show that chemistry is an innovative, responsible science, which happens every day around everybody. The selected topics may include sports, fashion, leisure, nutrition, or industrial raw materials. There will also be a hands-on laboratory, as well as a modern lecture room for 100 visitors to complete a visitor’s interactive experience.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission of Ambos & Weidenhammer and the Deutsches Museum, Munich.

chromatography,” Rehn explained. She said that part of the new exhibit will also allow visitors to experience learning about basic chemical principles such as acid-base reactions, and so on.

Rehn showed some drawings of how they think the new exhibition will look. Topics will be shown in what they call islands, without a shell or membrane (Figure 5-6). The interior of each island will hold a core element of the exhibition, as well as text, graphics, original objects, and demonstrations. She said that the challenge for chemistry will be showing something that is really too small to be seen: “Unlike an airplane or a combustion engine, I cannot put molecules on display in a glass case.” They will try to show everyday products that receive their special properties thanks to chemistry. Also, there will be both historical and modern objects, such as analytical instruments, laboratory equipment, and materials samples. Rehn showed a sketch from a demonstration of hydrogen bonds, where visitors can move one water molecule with a handle on it, and as they do so they can see how the intermolecular forces act on the other water molecules around it, and how they rearrange themselves accordingly. Future visitors will be able to do chemistry experiments in a hands-on laboratory and again take part in lectures in the auditorium.

Rehn finally showed drawings of the auditorium and laboratory complex in the new exhibition. She explained that the exhibits will be located in such a way that the visitors will walk along a time line showing the laboratories from the sixteenth century up to today. “While visitors will be able to see the historical laboratories like three-dimensional paintings, they will be able to walk into the hands-on laboratory and run their own experiments,” Rehn added.

THE MUSEUM AT THE CHEMICAL HERITAGE FOUNDATION

The next speaker highlighted a museum completely dedicated to chemistry. Shelley Geehr described the Chemical Heritage Foundation (CHF) as a library, a museum, and a center for scholars. She said, “We like to say that we tell the story of chemistry, we don’t do chemistry.” Through its museum and public program, CHF fosters an understanding of chemistry’s impact on society—-through its collection, research, and fellowships. Geehr explained that the museum is the newest part of CHF, having just opened in 2008. For a long time, she said, CHF was a library and a center for scholars. “We did a lot of collecting of materials, the papers of scientists, their old instruments, artwork, objects, artifacts, things that told the story of chemistry through time. We came to a point where we realized that there was a need and an interest in making these items more accessible, not just accessible to our scholars and our researchers, but to a broader public,” said Geehr.

CHF is located adjacent to Independence National Historical Park, which has helped attract visitors to the museum. Geehr said they take advantage of the fact that Independence Historical Park has more than a million visitors a year, and many of them go by CHF and end up going in. The CHF museum had about 15,000 visitors in its first year of operation, with almost half of them from outside the Philadelphia area. At the same time, CHF is not open on weekends, which significantly affects museum attendance.

The main exhibition CHF has is called Making Modernity. It is a permanent exhibition and has a range of interesting items: fine art, laboratory equipment, rare books, and everyday objects. The items are from the 1600s to the present. The aim

of the exhibit is to show how chemistry touches everyday life. Geehr said: “I think you have heard that over and over again this afternoon. That is what really works—to show people where chemistry exists in their everyday life.” As an example, she mentioned computers and how making a computer chip is a chemical process.

CHF exhibits cover a range of topics, from alchemy, to synthetics, to the chemical instrument revolution. She showed some cartoons poking fun at scientists and other chemical artwork. She noted that CHF has one of the largest collections of alchemical paintings in the world, and these paintings are a wonderful way to show people how science has been a part of our lives. She added, “Investigation has always been a part of our life, and it used to be done within the home, [we] show people that this is very much a human endeavor. That is our strength, to show how these things fit in context, to show through art, through objects, rather than through the individual experiments or the hands-on discoveries.”

One example of an interesting everyday object Geehr showed was a wedding gown made out of an Army surplus nylon parachute (Figure 5-7) from World War II. She thought it was a wonderful story to tell, how after the war “people used fabrics that were designed for other purposes and were able to change them and transform them.”

CHF also does public programming. There are tours and themed talks, as well as informal lectures. The goal of these programs is to provide the public with more tools to understand contemporary issues, to appreciate the role of chemical sciences in everyday life, and also to provide people in the field—the science and technology professionals—with a broader perspective. The museum is aimed at the high school and higher level, and scheduled tours are offered to high school and college groups, as well as to business groups visiting the conference center. Staff have developed three tours with a task force of practicing teachers and a couple of education consultants, called Chemistry in the Public Eye, Elements of Knowledge, and Creative Chemistry, each of which provides a different-themed way to go through the museum exhibition. They also customize tours as needed.

FIGURE 5-7 Everyday objects. A wedding gown made out of an Army surplus nylon parachute from World War II.

SOURCE: Shelley Geehr, Chemical Heritage Foundation permanent collection.

Another activity Geehr mentioned is participation in a science café3 CHF started called Science on Tap, in collaboration with four other Philadelphia science institutions: the Academy of Natural Sciences, the American Philosophical Society Museum, the Wagner Free Institute of Science, and the Mutter Museum of the College of Physicians. She said that it is an inexpensive and amazingly successful program. The café takes place the second Monday of every month, with each group taking turns to bring in a speaker. The format includes a very brief lecture followed by an extensive Q&A in a bar. She said it has been “wildly successful.” The first one had 50 people, and they have never had less since then, “even during the Philly playoffs!” said Geehr.

Another successful activity is CHF’s First Friday program. CHF is located in Old City Philadelphia, and many art galleries in that area stay open late on the first Friday of every month. There are many people around at that time, strolling around, looking at art, getting something to eat, and having drinks. CHF stays open late too and offers activities to attract visitors to the museum. Activities include making molecular origami, batteries out of lemons, and sun prints. Gehr noted, “It is amazing, the number of young people and adults who come in. They sit down, they will work on a small project for 20 to 30 minutes, and while they are doing this, we have someone walking around in a very casual way, talking about the science or the chemistry of what they are doing.” She said that last December they made papier maché ornaments and had a staff member who is a chemist talk about starch chemistry. People had to leave the ornaments behind because they were too wet, but they came back the following Monday to get them. “So it tells you that they had a good time, they valued it,” said Geehr.

In addition to the museum and activities, CHF also has a magazine, which Geehr described as its touchstone. “It has been around since the beginning. We use it to tell a variety of stories about the history of chemistry. We get tons of letters, tons of people coming up to us saying we love your magazine, particularly teachers. A lot of teachers find ways to use these features in their classroom.” The magazine staff also works closely with CHF web staff to expand the communication of

__________

3There are many science cafés in place across the county. For more information, see http://www.sciencecafes.org/ (accessed April 13, 2010).

content. The magazine only comes out three times a year, but staff would like to move more of the content to the web.

CHF has additional features on the web, such as its weekly podcast called Distillations.4 Geehr said that CHF has been producing the award-winning Distillations program since 2007 (the New York Festivals gave CHF three bronze medals for the podcasts in 2009). CHF also has three blogs, which she said all have very distinct voices. One is for the CHF scholarly community; one is the CHF president’s blog, where he talks about a variety of topics that interest him; and the third is called “The Center,” which highlights research and other activities by scholars in the CHF Center for Contemporary History and Policy.

Gehr noted that CHF is also getting involved in social media, such as Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube. She said that Flickr has been particularly valuable for CHF, because the images get picked up and used in various places. “Jezebel, which is a feminist blog, picked up an image of our chemistry set for girls, a beautiful chemistry set in a pink box. It is actually called a lab technician’s set for girls,” Geehr added. She said that there were more than 100 comments on the image. In another example, Wired Science picked up a CHF image of litmus paper. “We have had successes like that, a way to get our collections out in the world and get people to talk about them,” she said.

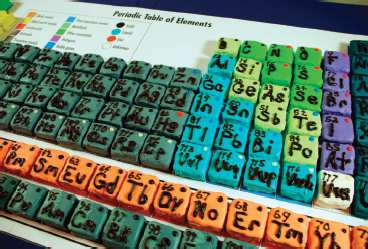

Geehr ended with an image of CHF’s anniversary cake, on the first anniversary of its museum. It was a Periodic Table of Cupcakes (Figure 5-8), which was featured on a blog as well. She said there were two young women, who just started an AP chemistry course in their high school, who planned to get H and I—hydrogen and iodine—spell HI, and then eat their cupcakes. Geehr reported that “unfortunately they got there a little too late so they couldn’t do that. But there was such enthusiasm to do something like that. They made their mother drive them in from the suburbs and they were just lovely.”

She said, “I think there is a great deal of hope going forward. I think telling the stories, the people, the innovations, the way it affects our lives each and every day, I think that is the way to truly draw people in, and show them beautiful things, show them artwork, show them Bakelite buttons, and they get it.”

The final speaker on chemistry in museums was Pete Yancone, from the Maryland Science Center. “If you visit Maryland Science Center you won’t find any [chemistry-specific content], at least nothing labeled Hall of Chemistry,” said Yancone, but he explained how the museum provides chemistry content and experiences in a variety of ways. He described the Maryland Science Center as a typical science center. He said it was recently renovated, but chemistry is not one of the core group of exhibits. He said, “That makes it more incumbent on my staff to recognize the opportunity for chemistry and to extract it from those kinds of experiences that we do have and that do come through the museum.”

FIGURE 5-8 Periodic Table of Cupcakes. An arrangement of cupcakes in the form of a Periodic Table of the Elements was created to celebrate the first anniversary of the opening of the Chemical Heritage Foundation Museum. People in the lobby could not wait to get into the room to have their cupcake on a Friday night in October.

SOURCE: Shelley Geehr, Chemical Heritage Foundation.

Yancone elaborated on some of the more practical aspects of trying to implement large-scale chemistry exhibits and demonstrations in museums and what prevents some museums from doing more. He noted that it is not trivial to incorporate chemistry into a museum. Yancone said, “This is not the kind of thing that says, if only we had a little more energy or I had one more staff person, I could overcome all this and, presto, I would have a chemistry exhibit. Safety is a paramount thing. On the one hand you are trying to create a sense of ease around chemistry, but you also have to keep the fire extinguisher at hand. You also have to make sure that the materials that you have designed the exhibit with are going to withstand it.”

Yancone explained that staffing is a critical issue, because staff need to be comfortable with the activities, otherwise any uneasiness they have will register very quickly with the audience. Sometimes staff require special training to handle chemicals. The museum typically doesn’t have a staff chemist; there are volunteers, however, who have worked in the field or who have taken some course work. Finding or hiring a chemist is not always possible.

Chemistry exhibits are also expensive, said Yancone. “It is not like some exhibits where you can build it and 5 years later you have spent nothing more than changing the light bulbs on it and maybe sending the cleaning crew through. If you are doing chemistry, you have got to keep the chemistry coming,” he added. This can be the deciding factor for museums to create a chemistry exhibit versus one on physics or other topics.

Yancone also pointed out, “Good chemistry, exciting chemistry is messy chemistry.” He said that this affects safety

__________

4For more information, see the Chemical Heritage Foundation Distillations website at www.chemheritage.org/community/distillations/index.aspx (accessed November 30, 2010).

and the facility itself. Disposal of used chemicals is a major concern, particularly for outreach and travel to schools. “What do you do with this stuff? You are left with one collection of chemicals that now becomes something else. Can you leave them at the school? Maybe not. You bring them back, and then what do you do with them?” Yancone added.

On a positive note, Yancone said that chemistry is very popular: “every survey we do of our visitors, they want to do chemistry. Their sense of the chemistry that they want to do is not electron dot diagrams. They don’t want to come in and calculate the probability of electron orbits. They want to mix stuff together and see what happens.”

In terms of exhibits, Yancone pointed out that there is a big difference between interactive and static displays, and there is a reason to have both in a museum. They have tried interactive chemistry exhibits with mixed results. They had an acid-base titration, where the reagents were metered out with the push of a button. It only lasted for about a week. The plan had called for the exhibit to be filled about once a day with reactants, but once it was opened to visitors, 5 liters of the chemicals disappeared in less than an hour. Five milliliters of reactant was metered out every press of the button. Yancone lamented, “It turns out it was really motivating for visitors to press that lever and get 5 milliliters of stuff, and like rats in a cage, they were pressing away, because if 5 milliliters works, 10 milliliters must be at least twice as good.”

Yancone noted the special importance of demonstrations in a museum. He said, “It is part of a noble tradition.” He said that many people will remember even a decent display of chemical phenomena, whether it is a university celebrating Chem Day, the college fair, a science museum, or the World’s Fair. He recalled seeing DuPont’s Wonderful World of Chemistry at the ‘64 World’s Fair. He said, “I had forgotten all about it until one day on our demonstration stage I realized I was doing that demo and was surprised to remember it in that context.” Yancone noted, however, that demonstrations are for the most part passive. Sometimes visitors may be included, but this is always a judgment call. “One of the concerns that we have is whether a volunteer adds something to the presentation or not,” said Yancone. He said the best thing about demonstrations is the spectacle. He said it is the kind of thing that works really well for promotional purposes.

Yancone said that IMAX has now reached into the chemical arena with programs such as the Molecularium show.5 He said that the planetarium could also become a place where you can display medium crystal lattices. He also mentioned the topic of facilitated lab experiences, such as the cell biology experiments that Kirsten Ellenbogen discussed. Maryland Science Center also received a Dreyfus grant to provide similar activities, which included biochemical and inorganic chemical experiences.

The challenge in those spaces, Yancone said, is to make them meaningful. “As a visitor, you walk in, you sit down, the staff provides you with materials, or you sit at a bench that is already pre-stocked. It is really fancy. You get to put on a white coat before you sit down, and maybe you glove up and you wear the safety glasses.” The experience is ideally an investigation, but sometimes it is just cookbook chemistry. The visitor follows a procedure with computer guidance, and everything works. However, he said, occasionally the computer or the program text will lead the visitor through branching, and there are choices to make and predictions to make. “Then you are actually doing an investigation,” said Yancone, and “visitors really like this stuff. They are doing it hands on. Even when it doesn’t work for them, they are really happy that they had the experience.”

Another aspect of the museum is conducting classes and workshops. Yancone described how the classes and workshops often help supplement the exhibits. For example, he discussed a new exhibit coming to the museum on marine archeology and shipwrecks. He said that part of the experience is about conservation of objects removed from the bottom of the ocean, which is a great opportunity to do electrochemistry. “When you don’t have a chemistry exhibit, this is where you put your chemistry,” said Yancone. The big challenge though with classes or experiences for school groups, drop-in weekends for visitors, especially families, Yancone said, is that “you have got somebody who is middle aged walking in with a teenager, walking in with a 5-year-old. The experience has to work for all of them.” He noted that they also offer an overnight camping program and after-school and homeschooler programs. “All of those are out-of-school kinds of experiences. There the audience is school age children, but they are not in their school mode and that makes them operate differently,” he added.

Another challenge of conducting chemistry activities, Yancone said, is “there is always a dynamic tension between education and marketing.” He said that it is easy for the marketing staff to declare that every chemical experience is somehow chemical magic. However, many visitors cannot tell the difference between magic and chemistry, so while the education department undersells the magic piece, “the marketing department always stuffs that in,” he added.

Yancone also talked about the museum’s involvement in promotional events. “Things that are event based certainly garner media attention. Where does the local TV outlet turn when it wants to hear about, I don’t know, the fact that air quality has been down over the city for the past week because of some temperature inversion. They can’t interview their own meteorological staff, so they have to talk to somebody and, fine, come to the science center. When National Chemistry Week (NCW) takes place, especially on the weekday, where are you going to go to find an audience? It is October. The museum would be a good place to try,” he explained.

A topic that hadn’t been discussed much by other speakers is the role of the museum store. “Much like our surveys of visi-

__________

5IMAX Molecularium: Molecules to the Max, www.moleculestothemax.com/ (accessed November 30, 2010).

tors that say they all want to do chemistry,” Yancone said, “it turns out that the science store at the Maryland Science Center, when they ranked what they sell, dinosaurs is number one, right behind it is anything related to chemistry.” Even though there is not a strong presence of chemistry in the museum, it is what people are walking out of the store with. Space comes after that. He mentioned that at one time there were some science stores at museums that turned into a local resource for labware and reagents, but this didn’t last long due to liability and security issues.

Yancone concluded by talking about how the museum uses the Internet. The museum website provides extensions to exhibits and activities. In the case of chemistry, he said, all of the chemistry demos have activities that can be done at home. For example, when the double blizzard hit the East Coast last year, the museum found that the hits on its website were those take-home activities.

Note: This session covers topics introduced by speakers and participants in the immediate and preceding workshop sessions.

Bill Carroll pointed out that about 20 years ago, the DuPont slogan was “Better Living through Chemistry,” showing how its business was connected to the experience and quality of life. He said that a lot of what had been discussed during the afternoon session focused on the relevance of chemistry to everyday life. However, now the DuPont slogan is Miracles of Science, Carroll pointed out. He then posed the question to workshop participants, “Do we still have the sense of the miraculous; do we still have the gee-whiz factor for the kinds of audiences that you are attracting to your programs? Or is some of that getting lost behind a greater emphasis on relevance?”

Yancone responded that some of that “gee whiz” factor has been lost. He said, “There was a time when people lived closer to real life, not so much a virtual experience. I think about my neighborhood. Five years ago I could see kids riding bikes and playing outside. Now they are all inside playing videogames where they are riding bikes and playing sports online. If you looked under your kitchen sink, you found ammonia and vinegar and Drano, and Drano was labeled as lye. Now there are cleaning products that have fancy names and fancy packaging, but nobody knows what is inside the containers, and they all have Mr. Yuck stickers on them and you are not supposed to get near them.”

On the one hand, he said he sees young people impressed by things that he wouldn’t have considered so impressive, because they have not seen the phenomenon before. For example, he said “If you bring 8-year-olds in and develop a print in black and white with some chemistry, they are in awe. They can operate a digital camera, they can process the image, they can give you 10 ways to print it, but seeing the chemical process that produced the black and white image, I guess I am still impressed with that myself, but not the way they react to it.”

Geehr believes that understanding how relevant something is, is a “gee-whiz” moment for a lot of people. “If you look at some of the younger people, they have never lived in a world without plastic. They don’t understand that there used to be a time when these things were difficult or complicated.” She said that one of the things they have in the CHF museum, which is a little shocking to people are tools that physicians use for diphtheria. As the throat closed, these stainless steel devices were shoved down the throat to open it and prevent people from suffocating.

No Chemical Formulas, Ever

A participant asked Geehr about the use of chemical formulas and molecular structures in the CHF museum: “How important do you think [structures are] as a mediator in public understanding of what chemistry is all about?”

Geehr responded that as a history museum, CHF has concentrated on telling the story and explaining it, but not really showing the chemistry explicitly. “So that is our out, that we are a history place, so we don’t have to do the little chemical diagrams.” However, she said that they do use them when it’s important. “We explain them, but occasionally you have to show that this molecule comes together with this molecule,” she said. For example, CHF has a temporary exhibit right now, which includes a computer program that allows visitors to build Viagra. She said that people spend a lot of time on it, “so you can do it, but you have to put it in context.” She also added, “It is a sad thing to say, but since the exhibition is about society’s reactions to chemical innovation and a lot of those reactions are to make fun of [it], we went with Viagra because it makes people laugh. You could have done it with anything, but Viagra makes people laugh.”

Batish agreed with Geehr. She said, at the Koshland they focus on how science is relevant to people in their daily lives, which includes chemistry at all different levels. However, it is not always necessary to show or work with chemical molecules.

Rehn commented that in the new exhibition at the Deutsches Museum, they want to make people curious about the chemical background of everyday stuff. They show visitors everyday items, and then the visitor is supposed to ask, “What does this have to do with chemistry?” Then they show the visitor the molecules and the formula, so they know it is not a secret science as in the time of alchemists.

Celebrating International Year of Chemistry

Nancy Blount, American Chemical Society, asked the panelists if any of them have anything particular planned around the International Year of Chemistry in 2011 (IYC 2011) or,

if not, could they suggest what they might do to bring this to the attention of their visitors. Also she asked them to suggest opportunities for collaboration.

Batish said collaboration is very important. “I think that would be an excellent way to bring different groups together. We would be more than happy to share our experiments with you, if you are planning to have anything in a different venue, a different city,” she added.

Rehn said they tried to open the new chemistry exhibition for IYC 2011, but it wasn’t possible, “so we are very sad about that.” They may have little activities showing chemistry in the yard of the museum or special lectures, but this is still uncertain.

Geehr said that the Chemical Heritage Foundation is very excited about the International Year of Chemistry. CHF is working with the American Chemical Society (ACS), the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE), the American Chemistry Council (ACC), and a number of groups within Philadelphia to launch the International Year of Chemistry here in the United States. A series of activities is scheduled for the first week of February, after the international launch in Paris. Also, CHF is working with a number of groups within Philadelphia to insert chemistry into unrelated events, such as the International Festival of Fine Arts. It is hoping to bring the Madame Curie interpreter in to perform.

Open Chemistry Labs

Rosenberg wanted to know more about how the Deutsches Museum plans to administer an open lab. He noted how the old chemistry exhibits were great, but they were behind glass as she said, and now the museum is trying to bring them out from behind the glass. He said he went to a museum in Switzerland, Technorama, where they had a totally interactive exhibit, but with no real guidance. “You could go up, put your hand in a glove box and play with liquid nitrogen and smash things. At the same time, there are examples such as at the museum in Maryland, where the kids pressed the button so much that the exhibit had to be taken out.”

Rehn said that in Germany, there are many labs with open plans, such as at the company Bayer. She said lots of universities do similar things—they have a laboratory, a basic set of reactions, most of the time including household chemicals such as ammonia, vinegar, lemon juice, or something similar. There is also a set of recipes. She said that fortunately they will have museum staff and Ph.D. students through a collaboration with the University of Munich Chemistry Department. The students will be involved in creating the classes, giving support, and evaluating the classes. She said, “I hope we can manage it, both personally and financially.”

Jeannette Brown noted that the CD-ROM the Koshland created on water will be great for the International Year of Chemistry. She also suggested that the CHF look into the National Science Foundation (NSF) History Makers program,6 about inspiring African Americans, which includes numerous oral histories of African-American scientists (saved digitally). She said it would be an excellent resource for involving African Americans during IYC 2011. She also mentioned the collaboration between CHF and the National Organization for the Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers (NOBCChE). Geehr also noted CHF’s collaboration with the African-American Museum in Philadelphia. She mentioned that they may bring Steve Lyon’s Percy Julian film back to the African-American Museum to launch Black History Month with a chemical theme.

Brown also recommended that all museums consider doing activities on the science of color. She said that she has a video and other materials about how Native Americans used natural plants to obtain dyes for textiles: “So a lot of this stuff can be done. It is all out there, you just need to organize it and show it.”

Chemistry in Prime Time

Ruth Woodall changed the subject to chemistry in TV and the movies. She mentioned that the 2010 theme for NCW is about chemistry in the movies: “Behind the Scenes with Chemistry!”7 She encouraged everybody to go to the website Chemistry.org/NCW and provide feedback. She also encouraged participants to go their local areas and help celebrate National Chemistry Week.

Bill Carroll brought up the popularity of the TV show CSI (Crime Scene Investigation). He said that he has talked to a lot of high school students and has asked them what made them think about studying forensic science and chemistry, and the answer usually connects back to the show. He said it seems that there are only a few places on television where one can find science in action, with people doing scientific work, such as the fictional drama CSI and the factual, but entertaining Mythbusters. He asked workshop participants what they see in CSI and Mythbusters. Are they a good thing, bad thing? “Who thinks CSI is a good thing from the perspective of informal chemistry education?” asked Carroll.

Paul Bryan said he is not a big devotee of CSI and NCIS but that he watches them occasionally. He thinks the show is connecting chemistry with something that students see as exciting. “Murder and mayhem and whatnot is much more exciting than test tubes and Erlenmeyer flasks,” he said.

Steve Lyons observed that he thinks, on balance, CSI and NCIS are positive because they do show science being used in a creative way. However, he lamented that the creators of these shows feel that in order to make science or mathemat-

__________

6For more information, see www.thehistorymakers.com/ (accessed January 1, 2011).

7See http://portal.acs.org/portal/PublicWebSite/education/outreach/ncw/ CNBP_025198 (accessed December 1, 2010).

ics palatable for people, they have to put it in the context of a crime-solving program. He said, “I wish there was some way to create a more realistic science program that didn’t have to shoehorn the science into that kind of program.”

For example, he thought it would be great to show chemistry in a different place and time, such as the new fictional drama Mad Men does with advertising in the 1950s and 1960s. He said, “I think what is needed is for some creative person … to come along to look at science in a new way and create a world [for chemistry] as original as Mad Men, and not shoehorn science into a crime-fighting program.”

Participants discussed how scientists are portrayed in TV shows in negative or in stereotypical roles…. However, Baisden mentioned an educational documentary television show that aired on PBS called Connections that depicted science and scientists in a positive way. She liked that show a lot, because it talked about scientific events, and then it connected them to societal benefits.

Lyons agreed that Connections was a wonderful program. He pointed out that it was British, and James Burke was the presenter. “He is very good at making surprising connections between these widely separated events in history and space.” He had a sequel called Connections II. Bill Carroll mentioned that there was also a videogame associated with the show.

Carroll then asked participants what is needed to have a good entertainment program. He said, “You need good characters, you need a good reason for the show to exist. There needs to be some central organizing problem around which you can get people interested. Is there a way of doing that without murdering somebody? Can you make research interesting without showing the 100 times you do something and it doesn’t work until the 101st time and it does? Is there a way of making that dramatic?”

Lyons said they were able to do that in the Percy Julian documentary, by focusing on highlights of his life. He said, “If we had done a film about the entirety of [Julians’s] chemical career, it would have been pretty boring, because there were a lot of dull moments in that life. We just picked the high points.”

Carroll followed up with another question, “How would you do [a show like Percy Julian] on a weekly [drama] series?”

Lyons replied that he wasn’t sure. “Looking at Mad Men as an example, Mad Men is a series about an advertising agency. There are some moments when they are focused on the nuts and bolts of putting together an ad campaign for Pan Am or for Kodak or whoever the client is who walks in the door. There is a lot of dynamics among the characters who work for this agency that brings you back to the period in the 1950s and the 1960s, which is very realistically recreated by the costumes and the sets,” he explained. What makes the series work, Lyons said, is that “it is not just about advertising, it is about those characters and their demons. The main character is a very troubled guy. Earlier in his life he changed his name in the war. He switched identities with a guy who was killed next to him in the war so he could escape his parents, and this has followed him for the rest of his life.”

Lyons said that in a similar way, someone could make an interesting fictional but realistic series about chemists. However, he warned that it cannot simply be focused on the chemistry. Chemistry can be part of the story, but more importantly, there have to be real characters with interesting lives and stories.

Mark Griep said Lyon’s idea reminded him of the 1930s and 1940s movie montages he has seen. For example, in the movie Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet, about the discovery of “compound 606,” it took the main character 606 tries to find the right antibiotic. In the movie, the discovery was shown as “a series of bubbling apparatus, guys working at benches, people writing in notebooks, and then finally the test works.”

Formalizing Informal Education

Carroll changed topics and commented that formal education is highly organized and informal education seems to be rather hit or miss. He asked, “If the goal were to appreciate that more of the education happens informally, how could we do a better job of organizing that so that people come in contact with it more often and absorb more? Or does it simply have to be random?” Andrea Twiss-Brooks argued that some of the attraction of informal education is that it is not highly organized, but it is a good idea to organize the content so that people come in contact with it. She said, “Children have their days organized in school, but they often find their spark outside of school where it is not organized and they are able to use their own pace.” She thinks it is a good idea though to have resources, such as takeaways that somebody could use during a blizzard. She said it is really important for informal education to develop and make those kinds of resources available.

Rosenberg mentioned the project he is involved in called SMILE, which stands for Science and Math Informal Learning Educators and the URL is Howtosmile.org. He said it is part of the NSDL, National Science Digital Library, and is meant to be a pathway to informal education resources. “We are trying to gather up activities that have been developed by museums and after-school programs around the country into one centralized place,” he said.

“I think about [Carroll’s] question a lot, actually. Most of the activities that we are cataloguing tend to be hit or miss in terms of, if you mix these two things together you see this effect. There is no higher level—if there is a higher-level explanation it tends to be lost in the doing and the seeing rather than the thinking,” said Rosenberg. He said that one of the goals of their project is to try and make it (1) so that people don’t keep reinventing the same activities, but can still compare the ones that have already been developed, and (2) to think about how to get to that next level for an activity. “The trick is, how do we take this informal field that is phenomenon based or story based in the case of media, and make it so that educators feel

more comfortable trying to get the learner, not just the kid, but the learner thinking about that next level and making a bigger organizational pattern,” said Rosenberg.

Carroll said that this related to Yancone’s earlier point, about chemical magic versus using a demonstration to educate “that it is not just about the whiz-bang, but how do you use the demonstration to get the attention and then to say, this is what is going on?”

Rosenberg responded, “Because it is free choice, because the museum in particular tends to be 5 minutes here, 2 minutes there, or home activities or after school—it tends to not be very coherent.” He is working on cataloging the activities in a more coherent manner so that an educator can start to think about what the learning goal might be for the activity, instead of just the phenomenon.

One difficulty for teachers is that they already have too much to do. He said that unless information is put in the hands of teachers in a highly organized way and the activities provided are easy to do, the uptake won’t happen. He said that a goal of the SMILE program should be to figure out how you make the transfer of information easy and accessible, so that it fits into a teacher’s lesson plan almost without thinking about it.

Rosenberg replied that what Carroll suggested is being addressed. The activities and resources being catalogued are open to everybody and are freely available online, and related activities are linked to each other. For example, there are the instructions for making Flubber, where Elmer’s glue and borax are mixed together to make a silly putty-like polymer. However, the explanation about polymers in most of the write-ups is somewhat limited, so there are links to related activities, such as using cutout paper models of monomers that can be mixed up in a bag with some Scotch tape to form a polymer model. He said the hope is that more people will become aware that the activities are free and available online and that some will also add activities to the site.

Making Videos

Pat Thiel mentioned that for the last few years she has been teaching physical chemistry at the university level, typically to students who are in their early 20s. She has observed that students in this age group are interested in unscripted YouTube videos, especially those by their peers. These videos have loud music background and are badly edited. She said, “They love that stuff. It seems like the worse it is, the more they like it. They appreciate anything that I put on, because then they don’t have to listen to me, but the more formal it is, the more professionally it is done, the more quiet they are and the more reserved they are in their reaction to it.”

She said a group of participants was talking about this at lunch—that there should be some level of encouragement to people to try and put their personal science online, but not too formally, or else it is not going to be as appealing.

Carroll asked her if she could engage her students to make their own videos that could be used for later classes.

Thiel said she was not sure, but that she planned to go back from this workshop and organize her research group to capture its research activities in a YouTube video online and, she added, “make it as badly edited as I possibly can.”

Lyons responded to Thiel’s comment, “Your experience with these videos reinforces the point that I was making this morning. Web video is a wide-open world, and nobody really knows how people are going to respond. So producing badly edited chemistry videos with rock sound tracks might in fact be the best way to go. Rather than producing little NOVA-ettes, the way I approached it. That might be totally the wrong way to do it.” He said it would be interesting for someone to experiment with different ways of using video to communicate chemistry and measure how people react to the different approaches.

Carroll then commented, “When I am talking to students, I will say, ‘When you go to a party and somebody asks you what your major is and you say chemistry, what do people do?’” He said the response is usually, “Ew, that was hard, no, I didn’t like that, I didn’t like my high school teacher, I got a D in that. You must be a brain. It is all that same thing.” He asked, “How can we do a better job as individuals of not getting to that moment, which I call the shutoff moment?”

He continued, “Part of it is to get people … to talk about themselves first, and then maybe you can talk about what you like about chemistry.” It is something the ACS has tried to do with the chemistry ambassadors, to work with people on their elevator speeches—15 seconds that allows a chemist to tell people what he or she does in a way that does not induce the shutoff speech.

He asked, “How comfortable do each of you who work in a science-y area [feel] … with the elevator speech?”

Bryan commented, “You don’t bring people to science by talking about science. You bring people to science by talking about something they are already interested in, and then you link it to science.” As an example, he talked about his work on biofuels. He said, “It is very nerdy and nobody looks like the people in NCIS or CSI, not nearly as interesting…. What we do is really fascinating, and it is very much linked to things that people are interested in. So when people ask me what I do, I say, ‘I am trying to save the world.’ Then I can lead from that.”

Bryan recommended that participants look up an article called the Seven Triggers of Fascination.8 According to the author Sally Hogshead, what really fascinates people comes down to seven different things—or what Bryan called “hooks—that grab their attention: lust, mystique, alarm, prestige, power, vice, and trust. He encouraged everyone to think about what they do that links to one of the seven triggers. “Once you have reeled them in, then you can start moving closely to the science, you have got them hooked,” said Bryan.

__________

8S. Hogshead. 2010. Fascinate: Your 7 Triggers to Persuasion and Captivation. New York: HarperCollins.

Lyons suggested that “maybe by the time you make the elevator speech, it is already too late, because those people you encounter on the elevator have a shutdown moment because they have been taught chemistry in high school and they react to it in a negative way.”

He said that he thinks this is a two-part problem. “Part of the problem is reforming chemistry education from the ground up so that people don’t have that experience. Then maybe you can make some headway on the informal side as well. But without reforming education too, you are always going to have the shutdown moment.”

Carroll thanked Steve and said, “Perhaps we should close for the day by saying reforming chemical education might possibly be the topic of another symposium.”