GOALS:

- Increase physical activity in young children.

- Decrease sedentary behavior in young children.

- Help adults increase physical activity and decrease sedentary behavior in young children.

Over the past 20 years, society has changed in multiple ways that have reduced the demand for physical activity and increased the time spent in sedentary pursuits. These trends have been evident even in the youngest children. It is well documented that many children under age 5 fail to meet physical activity guidelines established by expert panels (NASPE, 2009). The relationships among weight status, physical activity, and sedentary behavior are not yet fully understood in young children, but the limited research on this issue is growing. Some evidence suggests that higher levels of physical activity are associated with a reduced risk of excessive weight gain over time in young children (Janz et al., 2005, 2009; Moore et al., 2003), and similar evidence is more extensive for older children and adults (Hankinson et al., 2010; Riddoch et al., 2009). Additional prevention-oriented research to study the relationship between physical activity and risk of excessive weight gain over time in children is important.

Increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior are logical and accepted strategies for maintaining energy balance and preventing excessive weight gain. Recent evidence-based publications from government agencies, often developed using recommendations from scientific panels, affirm the importance of physical activity in reducing the risk of excessive weight gain. For example, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010 (USDA and HHS, 2010) counsels that for Americans 2 years of age and older, “Strong evidence supports that regular participation in physical activity also helps people maintain a healthy weight and prevent excess weight gain.” The Surgeon General’s Vision for a Healthy and Fit Nation (HHS, 2010) argues that “physical activity can help control weight, reduce risk for many diseases (heart disease and some cancers), strengthen your bones and muscles, improve your mental health, and increase your chances of living longer.” The 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (HHS, 2008a), targeted to children over 6 years of age and adults, states, “Regular physical activity in children and adolescents promotes a healthy body weight and body composition.”

This chapter thus presents policy and practice recommendations aimed at increasing physical activity and decreasing sedentary behavior in young children. Specifically, the recommendations in this chapter are intended to (1) increase young children’s physical activity in child care and other settings, (2) decrease young children’s sedentary behavior in child care and other settings, and (3) help adults adopt policies and practices that will increase physical activity and decrease sedentary behavior in young children. Each of these recommendations includes potential actions for its implementation. Recommendations for infants are included in an effort to highlight the need to begin obesity prevention practices in early life. The recommendations in this chapter target child care regulatory agencies, child care providers, early childhood educators, communities, colleges and universities, and national organizations for health and education professionals, urging them to collectively adopt policies and practices that will promote physical activity and limit sedentary behavior in young children.

GOAL: INCREASE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN YOUNG CHILDREN

Recommendation 3-1: Child care regulatory agencies should require child care providers and early childhood educators to provide infants, toddlers, and preschool children with opportunities to be physically active throughout the day.

For infants, potential actions include

- providing daily opportunities for infants to move freely under adult supervision to explore their indoor and outdoor environments;

- engaging with infants on the ground each day to optimize adult-infant interactions; and

- providing daily “tummy time” (time in the prone position) for infants less than 6 months of age.

For toddlers and preschool children, potential actions include

- providing opportunities for light, moderate, and vigorous physical activity for at least 15 minutes per hour while children are in care;

- providing daily outdoor time for physical activity when possible;

- providing a combination of developmentally appropriate structured and unstructured physical activity experiences;

- joining children in physical activity;

- integrating physical activity into activities designed to promote children’s cognitive and social development;

- providing an outdoor environment with a variety of portable play equipment, a secure perimeter, some shade, natural elements, an open grassy area, varying surfaces and terrain, and adequate space per child;

- providing an indoor environment with a variety of portable play equipment and adequate space per child;

- providing opportunities for children with disabilities to be physically active, including equipment that meets the current standards for accessible design under the Americans with Disabilities Act;

- avoiding punishing children for being physically active; and

- avoiding withholding physical activity as punishment.

Rationale

With adequate supervision and a secure perimeter, infants should be provided time each day to move freely and explore their surroundings. Physical activity may facilitate the achievement of gross motor milestones (Slining et al., 2010) and provides opportunities to expend energy (Li et al., 1995; Wells et al., 1996a,b). Research examining physical activity in infants is scarce, and even defining physical activity for infants is challenging. Thus, based on limited information, promot-

ing opportunities for movement such as reaching, creeping, crawling, cruising, and walking may be the most effective way to increase energy expenditure in children less than 1 year of age.

Although evidence in this area is limited, physical activity in infancy may help control excessive weight gain and maximize infants’ developmental potential. Obesity has been linked to lower levels of fitness and motor skills in older children (Cawley and Spiess, 2008; Frey and Chow, 2006; Graf et al., 2004; Mond et al., 2007; Okely et al., 2004; Shibli et al., 2008; Slining et al., 2010). Obesity in infancy in particular may delay the achievement of gross motor milestones (Shibli et al., 2008; Slining et al., 2010), and infants who attain motor milestones at later ages may be less physically active later in childhood (Slining et al., 2010).

Adults can help facilitate physical activity in infants by engaging with them on the floor or ground and encouraging exploration and free movement. Infants should spend some of this time in the prone position for supervised “tummy time” to help them attain motor milestones (Jennings et al., 2005; Kuo et al., 2008).

In designing indoor and outdoor spaces for children’s physical activity, attention increasingly is being paid to the developmental needs of toddlers and preschoolers (Trost et al., 2010; Ward et al., 2010), but much less attention has been paid to infants. For example, research is emerging on what characteristics of the physical environment are associated with more movement in children over 36 months of age, but little is known on this subject for children under 36 months of age.

Adults are responsible for creating the spaces in which infants move. The characteristics of these spaces theoretically can affect energy expenditure and obesity risk by influencing infants’ movements. However, data are lacking with which to link any physical characteristics of indoor or outdoor spaces to infant movement or body weight. Recommendations on the characteristics of spaces for infants that would prevent obesity are based on what is known about how to alter indoor environments to facilitate the achievement of gross motor milestones (Abbott and Bartlett, 2001; Bower et al., 2008). The magnitude or direction of the association among gross motor skills, movement, and body weight in infancy has not been elucidated. It is plausible, however, that the creation of indoor and outdoor spaces that support the achievement of motor milestones will facilitate movement and increase the possibility that infants can maintain a healthy body weight.

Infants are intrinsically motivated to explore their environments to obtain the visual, auditory, and tactile sensory input that fosters their cognitive and social development (Bushnell and Boudreau, 1993). Infants will generally approach and

interact with objects that elicit their attention. An infant’s attention and interaction will often be sustained if the objects have sensory properties that produce positive reinforcement. To explore the environment that is beyond arm’s reach, infants must develop the locomotor skills of rolling, creeping, crawling, or walking. The development of these skills can be enhanced by the sensory properties of surfaces on which infants are placed and by the presence of stable objects they can use for pulling up to a standing position or stepping with support (cruising) (Metcalfe and Clark, 2000). While infants are developing verbal language, they also rely on movement to communicate with others. Motor movement, therefore, is elicited in infants not just by the objects in their environments but also by their interactions with adults.

Broad consensus exists that young children should engage in substantial amounts of physical activity on a daily basis. In older children and adolescents, research has demonstrated a relationship between higher levels of physical activity and reduced risk for development of overweight and other physiologic indicators of elevated cardio-metabolic risk (HHS, 2008b). The 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans includes the recommendation that school-age youth engage in at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per day (HHS, 2008a).

Very little research has been conducted on the relationship between physical activity and health in infants. Some, but limited, research has been undertaken on the relationship between physical activity and body weight in toddlers and preschoolers. Nonetheless, the prevalence of overweight and obesity clearly has increased in these children (Ogden et al., 2010), and expert panels frequently have recommended that increased physical activity be targeted as one strategy for reducing the prevalence of obesity among children in these age groups (IOM, 2005; Strong et al., 2005). Some expert panels have recommended that 2- to 5-year-old children engage in 2 or more hours of physical activity per day (NASPE, 2009); however, these recommendations have not been based on dose-response studies of the effect of physical activity on health outcomes. A rationale for those guidelines is that toddlers and preschoolers need substantial amounts of physical activity to develop the fundamental motor patterns that underlie efficient and skilled human movement (Clark, 1994; Williams and Monsma, 2007).

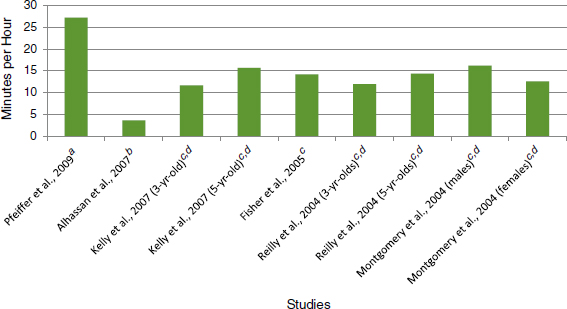

Toddlers and preschoolers, as compared with older children, clearly tend to be highly physically active. Several studies have examined levels of light, moderate, and vigorous physical activity in young children using accelerometry as an objective measure. Differing accelerometer cut-points used by researchers to dis-

FIGURE 3-1 Synthesis of studies examining levels of total minutes of physical activity per hour

(light, moderate, and vigorous) in awake children (3 to 5 years old).

NOTES:

aActiGraph accelerometer, used cut-point from Pate (Pate et al., 2006).

bActiGraph accelerometer, used cut-point from Sirard (Sirard et al., 2005).

cActiGraph accelerometer, used cut-point from Reilly (Reilly et al., 2003).

dMedian.

tinguish the threshold for light physical activity likely contribute to the different estimates of physical activity reported. Nonetheless, these studies demonstrate that children aged 3–5 are physically active (sum of light, moderate, and vigorous activity) for an average of about 15 minutes per hour of observation (Figure 3-1). This finding corresponds to approximately 3 hours of physical activity across a period of 12 waking hours. If this documented median is taken as a reasonable standard (e.g., those below the median should increase to that level), toddlers and preschoolers should be physically active for at least 3 hours per day. To adhere to that guideline, child care facilities should ensure that toddlers and preschoolers are active for at least one-quarter of the time they spend in the facility. For example, children spending 8 hours per day in care should be provided opportunities to be active for at least 2 hours.

Findings from physical activity interventions in the home and child care settings provide evidence of successful strategies to increase young children’s physical activity levels. Three family-based interventions demonstrated positive effects

(Cottrell et al., 2005; Klohe-Lehman et al., 2007; Sääkslahti et al., 2004). Cottrell and colleagues (2005) conducted a 4-week family physical activity intervention that included pedometers (for parents and children) and information on physical activity. Children in the intervention group significantly increased their steps per day relative to children in the control group (Cottrell et al., 2005). The other two studies used parental reports of children’s physical activity and found that young children had higher physical activity levels at the end of the intervention (Klohe-Lehman et al., 2007; Sääkslahti et al., 2004).

Some studies suggest that structured physical activity sessions implemented in child care settings can be effective in increasing physical activity levels among preschool-age children (Eliakim et al., 2007; Trost et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2009). Trost and colleagues (2008) conducted an RCT to test the effectiveness of an 8-week “move and learn” activity curriculum in the child care setting. This curriculum incorporated physical activity into 10-minute curriculum lessons in math, social studies, science, language arts, and nutrition education (Trost et al., 2008). During classroom time, children in the intervention group engaged in significantly more moderate to vigorous physical activity than children in the control group during weeks 5–8, and more vigorous physical activity during weeks 7 and 8 (Trost et al., 2008). When classroom and outdoor time were combined, levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity were similar between the two groups with the exception of weeks 7 and 8, when children in the intervention group had higher levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity (Trost et al., 2008). In the study by Williams and colleagues (2009), teachers in nine Head Start centers implemented a 10-week intervention consisting of 10-minute classroom physical activities (Animal Trackers). These activities effectively increased the amount of time children spent in structured physical activity, for a total of 47 minutes per week (Williams et al., 2009). Finally, Eliakim and colleagues (2007) conducted a group RCT that included a physical activity program for preschool children. The 14-week intervention included 45-minute sessions of circuit training and endurance activities 6 days per week. At the conclusion of the intervention, children in the intervention group had made significantly more overall steps per day, steps during school, and steps after school compared with children in the control group (Eliakim et al., 2007).

Two examples of environmental interventions in the child care setting had positive outcomes (Benjamin et al., 2007; Hannon and Brown, 2008). Hannon and Brown (2008) tested the effect of activity-friendly equipment on the playground, which was set up as an obstacle course. Children had significantly

increased the percentage of time spent in light (+3.5 percent), moderate (+7.8 percent), and vigorous (+4.7 percent) physical activity and significantly decreased the percentage of time spent in sedentary behavior (–16 percent) postintervention (Hannon and Brown, 2008). Benjamin and colleagues pilot-tested an environmental intervention in 19 child care centers. The intervention consisted of a director’s self-assessment, action planning, continuing education workshops, technical assistance, and reassessment (Benjamin et al., 2007). At the conclusion of the 6-month intervention period, the intervention centers had improved by approximately 10 percent based on the director’s self-assessment (Benjamin et al., 2007). In a larger trial involving 84 child care centers, however, a similar intervention had no significant impact on physical activity (Ward et al., 2008).

Young children should be provided with daily opportunities to be active outdoors when possible. Research has demonstrated that young children are more active outdoors than indoors (Brown et al., 2009; Klesges et al., 1990; Sallis et al., 1993). For example, Brown and colleagues (2009) found that only 1 percent of preschoolers’ indoor time consisted of moderate to vigorous physical activity, as compared with 17 percent of their outdoor time (Brown et al., 2009). Yet although young children are more active when outside, the potential exists to increase preschoolers’ physical activity levels further during outdoor play. Realizing this potential may require more training of adults in how to encourage children’s movement. Some evidence suggests that allowing more outdoor time for unstructured play may alone be insufficient to increase young children’s physical activity levels (Alhassan et al., 2007).

Several strategies have been identified to increase young children’s physical activity levels in outdoor settings. First, large playgrounds, particularly those with open space, are significantly associated with increased physical activity levels (Boldemann et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2009; Cardon et al., 2008; Dowda et al., 2009). For example, Dowda and colleagues (2009) found that preschoolers engaged in more moderate to vigorous physical activity in preschools with larger playgrounds compared with children in preschools with smaller playgrounds (Dowda et al., 2009). Second, providing portable playground equipment, such as balls or wheeled toys, significantly increases young children’s physical activity levels (Brown et al., 2009; Cardon et al., 2008; Dowda et al., 2009). Third, evidence indicates that young children are more active in outdoor spaces with less fixed equipment (Bower et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2009; Dowda et al., 2009). Finally, outdoor spaces with trees, shrubbery, and broken ground are positively associated with physical activity in young children (Boldemann et al., 2006). (In this study,

“broken ground” refers to spaces with clusters of trees present, rather than wide open spaces.)

Although the literature is limited with respect to how to increase moderate to vigorous physical activity while young children are indoors, doing so is important because children tend to be inactive while indoors. Bower and colleagues (2008) found that providing such opportunities was positively associated with moderate to vigorous physical activity (r = 0.50) and negatively associated with sedentary behavior (r = –0.53).

Physical activity also can be incorporated into activities designed to promote children’s cognitive and social development. Indeed, active learning has been shown to promote cognitive development (Burdette and Whitaker, 2005; Bushnell and Boudreau, 1993). Therefore, including training on the benefits of physical activity and how to promote active play and provide a positive environment for such play is advisable for child care providers.

Recommendation 3-2: The community and its built environment should promote physical activity for children from birth to age 5.

Potential actions include

- ensuring that indoor and outdoor recreation areas encourage all children, including infants, to be physically active;

- allowing public access to indoor and outdoor recreation areas located in public education facilities; and

- ensuring that indoor and outdoor recreation areas provide opportunities for physical activity that meet current standards for accessible design under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Rationale

Physical activity provides children with opportunities to expend energy. As discussed under the previous recommendation, although research on the relationship between physical activity and the control of excessive weight gain among young children is limited, evidence suggests that higher levels of physical activity are associated with a reduced risk of excessive weight gain. The importance of active play for children to promote their physical, cognitive, and emotional development is well established, and such play may help prevent overweight and obesity during early childhood and later in adult life (Berntsen et al., 2010;

Burdette and Whitaker, 2005; Dwyer et al., 2009; Ginsberg et al., 2007; Janz et al., 2002). Children at all ages need indoor and outdoor spaces that provide them with opportunities to play and be physically active. To promote physical activity, however, facilities need to be accessible, safe, and well designed to prevent serious injuries to young children. Adults and caregivers may limit young children’s playing in outdoor spaces and recreational parks for fear that they will be injured if playground surfaces and equipment are not safe or developmentally appropriate.

The Public Playground Safety Handbook issued by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC, 2010) offers detailed guidelines for the design of playgrounds and the selection of equipment and surfacing materials to ensure the safety of children. The commission also has guidelines for separating play areas for children of different age groups to avoid injuries during play and for designing pathways to prevent older, more active children from running into younger children with slower movements and reactions. These guidelines form the basis for the National Health and Safety Performance Standards (AAP et al., 2002) for out-of-home child care, which include detailed standards for a number of outdoor play area features, including size and capacity, as well as specifications for playground equipment. State and local enforcement of national standards for outdoor playgrounds and recreational facilities is key to providing young children (infants, toddlers, and preschoolers), under the supervision of their caregivers, with increased opportunities to be physically active outside of their homes or child care settings.

Neighborhoods and communities can affect children’s opportunities to be physically active through the provision of parks, open spaces, and playgrounds (AAP, 2009). In communities where these venues are limited, opportunities to use public school facilities can also be explored (IOM and NRC, 2009). Numerous reviews have examined the links between the built environment, including the availability of parks and playgrounds, and the physical activity of adults (Floriani and Kennedy, 2008; Kaczynskl and Henderson, 2008), and researchers have increasingly been interested in assessing the impact of the built environment on children’s, including preschoolers’, physical activity (Davison and Lawson, 2006). Thus, various surveys, assessment tools, and measurement approaches have been developed and used to evaluate the link between the quality of outdoor playgrounds for young children (under age 5) and their physical activity levels (Brown et al., 2006; Cosco et al., 2010; DeBord et al., 2005; Saelens et al., 2006). Behavioral mapping is one approach used to explore the relationship between a number of physical attributes, such as open areas, sand play, ground surface, play equipment, and pathways, and levels of physical activity (sedentary, light,

and moderate to vigorous physical activity) among children in a preschool setting (Cosco et al., 2010). Communities and local governments can benefit from the growing evidence and expertise in designing outdoor playgrounds and other areas to further help young children develop their gross motor skills and be physically active. Landscape architects and designers, environmental psychologists, and specialists can provide technical assistance and knowledge of how to design playgrounds using behavioral mapping methods and other science-based approaches to enhance the physical attributes of parks and playgrounds and attract young children to play and be active (see Box 3-1).

Among older children, those with disabilities appear to be at higher risk for developing obesity than those without disabilities (Chen et al., 2010; Rimmer et al., 2010). The cause of this increased risk is unclear, but lower levels of physical activity and higher levels of sedentary behavior may be one explanation, particularly for the subset of children with physical disabilities (Maher et al., 2007; Steele et al., 1996). To increase opportunities to be physically active for children with disabilities, both indoor and outdoor spaces for young children’s physical activity

Box 3-1

Behavioral Mapping: A New Approach to Link Outdoor Design with Physical Activity Levels

Behavioral mapping is a method that combines direct observation of the physical attributes of a location, such as a playground, with measurement of the physical activity behaviors of individuals. This mapping approach is based on two concepts: behavior settings (ecological units that are composed of people, physical components, and behavior) and affordance (perceived properties of an environment). The approach was recently used to investigate the relationship between different layouts, designs, and equipment locations in preschool outdoor playgrounds and the perceptions and abilities of preschoolers with respect to playing and being physically active. Behavioral mapping is a promising method for assessing not only the physical characteristics of recreational areas and playgrounds but also the impact of climate and seasonality on the year-round physical activity of children, as well as possible differences based on race and ethnicity in children’s perceptions and use of these behavior settings.

SOURCE: Cosco et al., 2010.

should be accessible to these children and contain equipment that meets their particular needs (Riley et al., 2008). This is true not only for child care and early childhood education programs but also for recreational facilities in the community. Meeting the standards for accessibility is most likely to be achieved by applying principles of universal design, which allow individuals of varying ages and abilities to be physically active with autonomy and safety (Preiser and Ostroff, 2001).

GOAL: DECREASE SEDENTARY BEHAVIOR IN YOUNG CHILDREN

Recommendation 3-3: Child care regulatory agencies should require child care providers and early childhood educators to allow infants, toddlers, and preschoolers to move freely by limiting the use of equipment that restricts infants’ movement and by implementing appropriate strategies to ensure that the amount of time toddlers and preschoolers spend sitting or standing still is limited.

Potential actions include

- using cribs, car seats, and high chairs for their primary purpose only—cribs for sleeping, car seats for vehicle travel, and high chairs for eating;

- limiting the use of equipment such as strollers, swings, and bouncer seats/chairs for holding infants while they are awake;

- implementing activities for toddlers and preschoolers that limit sitting or standing to no more than 30 minutes at a time; and

- using strollers for toddlers and preschoolers only when necessary.

Rationale

Energy expenditure through physical activity is one side of the energy equation that determines whether healthy weight can be developed and maintained. Physical activity in child care settings provides children with important opportunities to expend energy. As discussed under the previous recommendation, although research on the relationship between physical activity and the control of excessive weight gain among young children is limited, evidence suggests that higher levels of physical activity are associated with a reduced risk of excessive weight gain.

Because of safety concerns, infants often are physically restrained from physical activity through the use of confining equipment, such as car seats, strollers, bouncer seats, swings, high chairs, cribs, and playpens. Although these

devices help protect infants (e.g., cribs provide safe sleeping environments, and car seats protect infants during vehicular travel), they should be limited to their intended purposes in the interests of allowing physical activity and thus energy expenditure. The long-term health implications of overusing these devices are still unknown; however, a handful of case studies suggest that infants need to engage in unrestricted movement throughout the day to promote energy expenditure and physical development (Garrett et al., 2002; Thein et al., 1997). Concern about the effects of restrictive devices was sufficient to lead Delaware in 2007 to require licensed child care centers to limit time spent, while awake, in any confining equipment, such as a crib, infant seat, swing, high chair, or playpen, to less than one-half hour (http://www.nrckids.org).

Recent reports suggest that overconfinement to cribs and playpens can result in infants’ spending too much time on their back. Although supine sleeping is important because it helps prevent the occurrence of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), infants who spend too much time on their back are at risk for developing plagiocephaly, a deformation of the skull that may negatively affect cognitive and gross motor development later in infancy (Kordestani and Panchal, 2006; Robinson, 2010). Indeed, health practitioners have linked the increased incidence of plagiocephaly with national public campaigns to reduce SIDS (Bialocerkowski et al., 2008; Black, 2009; Cowan and Bennett, 2009; McKinney et al., 2009; Mildred et al., 1995). Thus while these important initiatives have reduced the incidence of SIDS, they may have unintended consequences associated with infants’ supine sleep position. Parents and other caregivers can play an important role in averting these consequences by reducing the time infants spend in cribs and playpens when they are not sleeping and in general limiting the use of restrictive devices to their intended purpose.

Young children spend a large portion of their day engaged in sedentary behavior (Oliver et al., 2007). Several studies have used accelerometry for objectively measuring physical activity and sedentary behavior in young children. When accelerometer data are expressed as minutes per hour of observation, the amount of time young children spend in sedentary behavior ranges from 32.8 (Pfeiffer et al., 2009) to 56.3 (Alhassan et al., 2007) minutes per hour. The average across studies is approximately 45 minutes per hour of sedentary behavior (Alhassan et al., 2007; Cardon et al., 2008; Cliff et al., 2009; Fisher et al., 2005; Kelly et al., 2007; Montgomery et al., 2004; Pfeiffer et al., 2009; Reilly et al., 2004). Direct observation also has been used to measure physical activity and sedentary behavior in young children, and it provides contextual information, including the types,

locations, and social contexts of those behaviors. In a study of 476 3- to 5-year-old children from 24 child care centers, children spent approximately 89 percent of observed intervals in sedentary behavior: sitting, lying down, and standing (Brown et al., 2009).

Within the child care setting, several factors have been shown to either increase or decrease young children’s sedentary behavior. One study found that young children in child care centers with high use of electronic media (e.g., televisions, movies, computers) had higher levels of sedentary behavior than young children in centers with low electronic media use (Dowda et al., 2009). Conversely, two studies (Bower et al., 2008; Dowda et al., 2004) found no association between use of electronic media in child care and children’s sedentary behavior. The differences between these study findings have been attributed to differences in the measures of media use (Bower et al., 2008; Dowda et al., 2009). Higher-quality child care centers—defined as having an Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Revised (ECERS-R) score over 5 (Dowda et al., 2004, 2009) and higher scores on the physical activity environment and active opportunities scales of the Environment and Policy Assessment and Observation (EPAO) instrument (Bower et al., 2008)—are associated with less sedentary behavior in young children. Other factors associated with less sedentary behavior in child care include more portable and less fixed playground equipment (Bower et al., 2008; Dowda et al., 2009) and larger playgrounds (Dowda et al., 2009).

The potential health effects of sedentary behavior have not been studied in young children. Excessive exposure to television watching, a behavior that is usually sedentary, may be associated with increased weight gain in young children (Jackson et al., 2009; Jago et al., 2005; Janz et al., 2002; Proctor et al., 2003), an issue addressed in Chapter 5. In addition, there is concern that prolonged bouts of sedentary behavior may have negative health consequences. This issue has been studied in adults (Hamilton et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2003) but has not yet been studied in young children. Nonetheless, it appears to be appropriate for young children to avoid long periods of inactivity in order to increase their opportunities for energy expenditure.

GOAL: HELP ADULTS INCREASE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND DECREASE SEDENTARY BEHAVIOR IN YOUNG CHILDREN

Recommendation 3-4: Health and education professionals providing guidance to parents of young children and those working with young children should be trained in ways to increase children’s physical activity and decrease

their sedentary behavior, and in how to counsel parents about their children’s physical activity.

Potential actions include

- colleges and universities that offer degree programs in child development, early childhood education, nutrition, nursing, physical education, public health, and medicine requiring content within coursework on how to increase physical activity and decrease sedentary behavior in young children;

- child care regulatory agencies encouraging child care and early childhood education programs to seek consultation yearly from an expert in early childhood physical activity;

- child care regulatory agencies requiring child care providers and early childhood educators to be trained in ways to encourage physical activity and decrease sedentary behavior in young children through certification and continuing education; and

- national organizations that provide certification and continuing education for dietitians, physicians, nurses, and other health professionals (including the American Dietetic Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics) including content on how to counsel parents about children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviors.

Rationale

Based on what is known about the impact of training for child care staff on children’s physical activity and the need for more training opportunities expressed by child care providers, a recommendation on training for health and education professionals on ways to increase children’s physical activity is appropriate. Millions of young children spend substantial amounts of time in child care and early childhood education programs. The social and physical environments provided by these programs have an important influence on children’s physical activity and sedentary behavior. Those environments are established by the administrators, child care providers, and early childhood educators who design, manage, and deliver the programs. Research has shown that staff training influences children’s physical activity in child care centers. More teacher education (Dowda et al., 2004) and training (Bower et al., 2008; Dowda et al., 2009) in physical activity are associated with higher levels of physical activity in children. For example, teacher training in physical activity was found to be positively associated with children’s mean

activity level (r = 0.40) and the percentage of time children spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity (r = 0.35) and negatively associated with the percentage of time children spent in sedentary behavior (r = –0.35) (Bower et al., 2008). In addition, training in physical activity was positively associated with more teacher behavior supportive of physical activity (r = 0.48) (Bower et al., 2008).

A major examination of issues related to training of employees in child care and child development centers with regard to physical activity and nutrition was undertaken in the state of Delaware (Gabor et al., 2010). Training needs and recommendations for future training activities were studied through an extensive series of focus group discussions. Child care providers acknowledged the need for more training opportunities, technical assistance, and resources. Specifically, child care center directors stated that child care providers and early childhood educators needed more ideas and resources for structured physical activities, especially those that are linked to the development of gross motor skills. In addition, child care providers preferred a hands-on training approach for learning how to incorporate structured activities into the child care setting.

Several national organizations have made recommendations regarding training in the provision of physical activity programs for child care providers and early childhood educators (AAP et al., 2010; Benjamin, 2010; McWilliams et al., 2009). Training opportunities also should be provided for special education teachers who have specific responsibility, under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, for working with children with disabilities.

There are resources available to assist caregivers with ways to encourage physical activity in young children. Information can be found at the following websites, among others:

- National Association for Sport and Physical Education: http://www.naspeinfo.org

- National Association for the Education of Young Children: http://www.naeyc.org/

Adults control where and how children under age 5 spend their time. These decisions influence the variety, frequency, and intensity of children’s movement experiences and thus their motor development, energy expenditure, and body weight. For example, whether an awake infant in the home is spending time constrained in a car seat or prone and moving freely on the floor may have implications for that infant’s gross motor development, movement, and energy expendi-

ture. Whether a toddler or preschooler at home spends time watching television or playing outdoors may have similar implications. These decisions about allocation of time across activities also affect children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development. Thus it is the cumulative impact of decisions made by adults that shapes the development of the bodies and minds of young children.

Of all the adults who make decisions about activities for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers, it is parents (or guardians) who have the greatest influence because children at this age still spend the majority of their time in their parents’ care. This is true even for children in full-day child care or preschool. Therefore, how children spend the time they are with their parents and the nature of the physical environment in the home are two key leverage points for preventing obesity from birth to age 5. Parents establish the household policies and practices in these two areas. Therefore, for public policy to affect these areas, it must reach parents.

Parents seek advice in raising their children from those they trust. Outside of friends and family, the professionals they often trust include the following: health care providers; child care providers; early childhood educators; and those working in home visiting programs, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Cooperative Extension programs. These professionals function within institutions, programs, and professional organizations that can develop policies and practices that influence the content and frequency of professionals’ communication with parents on a number of issues affecting children’s physical activity.

The first two goals of this chapter involve recommendations designed to alter settings outside the home by changing physical environments and the ways adults in those settings interact with children and allocate children’s time across activities. It would be ideal for parents to implement many of these same recommendations at home. Parents can be aided in this effort by the professionals from whom they already seek advice about parenting. For parents to be receptive to this advice, they must feel encouraged by these professionals rather than blamed, and the advice must be practical and compatible with the parents’ values. Messages about physical activity and sedentary behavior also must be consistent across settings—from the pediatrician’s office, to the WIC clinic, to the child care center.

Finally, professionals can empower parents to change children’s environments and activities outside the home to encourage physical activity and decrease sedentary behavior. Parents need the support of professionals to advocate for these changes in their communities, especially in settings where their children receive

child care and early childhood education. Parents’ expression of their opinions can change the indoor and outdoor environments in all these settings, the ways in which nonparental adults interact with their children, and the kinds of activities their children engage in while away from home.

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2009. The built environment: Designing communities to promote physical activity in children. Pediatrics 123:1591-1598.

AAP, APHA (American Public Health Association), and National Resource Center for Health Safety in Child Care and Early Education. 2002. Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards; Guidelines for Out-of-Home Child Care Programs, 2nd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: AAP and Washington, DC: APHA.

AAP, APHA, and National Resource Center for Health Safety in Child Care and Early Education. 2010. Preventing Childhood Obesity in Early Care and Education. http://nrckids.org/CFOC3/PDFVersion/preventing_obesity.pdf (accessed October 22, 2010).

Abbott, A. L., and D. J. Bartlett. 2001. Infant motor development and equipment use in the home. Child: Care, Health and Development 27(3):295-306.

Alhassan, S., J. R. Sirard, and T. N. Robinson. 2007. The effects of increasing outdoor play time on physical activity in Latino preschool children. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity 2(3):153-158.

Benjamin, S. E. 2010. Preventing Obesity in the Child Care Setting: Evaluating State Regulations. http://cfm.mc.duke.edu/wysiwyg/downloads/State_Report-NC.pdf (accessed October 22, 2010).

Benjamin, S. E., A. Ammerman, J. Sommers, J. Dodds, B. Neelon, and D. S. Ward. 2007. Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC): Results from a pilot intervention. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 39(3):142-149.

Berntsen, S., P. Mowinckel, K. H. Carlsen, K. C. Lødrup Carlsen, M. L. Pollestad Kolsgaard, G. Joner, and S. A. Anderssen. 2010. Obese children playing towards an active lifestyle. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity 5(1):64-71.

Bialocerkowski, A. E., S. L. Vladusic, and C. Wei Ng. 2008. Prevalence, risk factors, and natural history of positional plagiocephaly: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 50(8):577-586.

Black, H. 2009. Back sleeping can flatten babies’ heads. Nursing New Zealand (Wellington, N.Z.: 1995) 15(8):4.

Boldemann, C., M. Blennow, H. Dal, F. Martensson, A. Raustorp, K. Yuen, and U. Wester. 2006. Impact of preschool environment upon children’s physical activity and sun exposure. Preventive Medicine 42(4):301-308.

Bower, J. K., D. P. Hales, D. F. Tate, D. A. Rubin, S. E. Benjamin, and D. S. Ward. 2008. The childcare environment and children’s physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 34(1):23-29.

Brown, W. H., K. A. Pfeiffer, K. L. McIver, M. Dowda, M. J. C. A. Almeida, and R. R. Pate. 2006. Assessing preschool children’s physical activity: The observational system for recording physical activity in children-preschool version. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 77(2):167-176.

Brown, W. H., K. A. Pfeiffer, K. L. McIver, M. Dowda, C. L. Addy, and R. R. Pate. 2009. Social and environmental factors associated with preschoolers’ nonsedentary physical activity. Child Development 80(1):45-58.

Burdette, H. L., and R. C. Whitaker. 2005. Resurrecting free play in young children: Looking beyond fitness and fatness to attention, affiliation, and affect. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 159(1):46-50.

Bushnell, E. W., and J. P. Boudreau. 1993. Motor development and the mind: The potential role of motor abilities as a determinant of aspects of perceptual development. Child Development 64(4):1005-1021.

Cardon, G., E. Van Cauwenberghe, V. Labarque, L. Haerens, and I. De Bourdeaudhuij. 2008. The contribution of preschool playground factors in explaining children’s physical activity during recess. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 5:11.

Cawley, J., and C. K. Spiess. 2008. Obesity and skill attainment in early childhood. Economics and Human Biology 6(3):388-397.

Chen, A. Y., S. E. Kim, A. J. Houtrow, and P. W. Newacheck. 2010. Prevalence of obesity among children with chronic conditions. Obesity 18(1):210-213.

Clark, J. 1994. Motor development. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior, edited by V. S. Ramachandran. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Cliff, D. P., A. D. Okely, L. M. Smith, and K. McKeen. 2009. Relationships between fundamental movement skills and objectively measured physical activity in preschool children. Pediatric Exercise Science 21(4):436-449.

Cosco, N. G., R. C. Moore, and M. Z. Islam. 2010. Behavior mapping: A method for linking preschool physical activity and outdoor design. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 42(3):513-519.

Cottrell, L., E. Spangler-Murphy, V. Minor, A. Downes, P. Nicholson, and W. A. Neal. 2005. A kindergarten cardiovascular risk surveillance study: Cardiac-kinder. American Journal of Health Behavior 29(6):595-606.

Cowan, S., and S. Bennett. 2009. Pursuing safe sleep for every baby, every sleep, in every place they sleep. Nursing New Zealand (Wellington, N.Z.: 1995) 15(6):12-13.

CPSC (U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission). 2010. Public Playground Safety Handbook. http://www.cpsc.gov/cpscpub/pubs/325.pdf (accessed June 3, 2011).

Davison, K. K., and C. T. Lawson. 2006. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children’s physical activity? A review of the literature. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 3(19).

DeBord, K., L. L. Hestenes, R. C. Moore, N. G. Cosco, and J. R. McGinnis. 2005. Preschool Outdoor Environment Measurement Scale-Poems. Winston Salem, NC: Kaplan, Inc.

Dowda, M., R. R. Pate, S. G. Trost, M. J. Almeida, and J. R. Sirard. 2004. Influences of preschool policies and practices on children’s physical activity. Journal of Community Health 29(3):183-196.

Dowda, M., W. H. Brown, K. L. McIver, K. A. Pfeiffer, J. R. O’Neill, C. L. Addy, and R. R. Pate. 2009. Policies and characteristics of the preschool environment and physical activity of young children. Pediatrics 123(2):e261-e266.

Dwyer, G. M., L. A. Baur, and L. L. Hardy. 2009. The challenge of understanding and assessing physical activity in preschool-age children: Thinking beyond the framework of intensity, duration and frequency of activity. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 12(5):534-536.

Eliakim, A., D. Nemet, Y. Balakirski, and Y. Epstein. 2007. The effects of nutritional-physical activity school-based intervention on fatness and fitness in preschool children. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism: JPEM 20(6):711-718.

Fisher, A., J. J. Reilly, L. A. Kelly, C. Montgomery, A. Williamson, J. Y. Paton, and S. Grant. 2005. Fundamental movement skills and habitual physical activity in young children. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 37(4):684-688.

Floriani, V., and C. Kennedy. 2008. Promotion of physical activity in children. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 20(1):90-95.

Frey, G. C., and B. Chow. 2006. Relationship between BMI, physical fitness, and motor skills in youth with mild intellectual disabilities. International Journal of Obesity 30(5):861-867.

Gabor, V., K. Mantinan, K. Rudolph, R. Morgan, and M. Longjohn. 2010. Challenges and Opportunities Related to Implementation of Child Care Nutrition and Physical Activity Policies in Delaware: Findings from Focus Groups with Child Care Providers and Parents. http://www.cshelwa.org/Resources/DelawareFocusGroup-FullReport-FIN.pdf (accessed October 21, 2010).

Garrett, M., A. M. McElroy, and A. Staines. 2002. Locomotor milestones and babywalkers: Cross sectional study. British Medical Journal 324:1494.

Ginsburg, K. R., D. L. Shifrin, D. D. Broughton, B. P. Dreyer, R. M. Milteer, D. A. Mulligan, K. G. Nelson, T. R. Altmann, M. Brody, M. L. Shuffett, B. Wilcox, C. Kolbaba, V. L. Noland, M. Tharp, W. L. Coleman, M. F. Earls, E. Goldson, C. L. Hausman, B. S. Siegel, T. J. Sullivan, J. L. Tanner, R. T. Brown, M. J. Kupst, S. E. A. Longstaffe, J. Mims, F. J. Wren, G. J. Cohen, and K. Smith. 2007. The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics 119(1):182-191.

Graf, C., B. Koch, E. Kretschmann-Kandel, G. Falkowski, H. Christ, S. Coburger, W. Lehmacher, B. Bjarnason-Wehrens, P. Platen, W. Tokarski, H. G. Predel, and S. Dordel. 2004. Correlation between BMI, leisure habits and motor abilities in childhood (CHILT-project). International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders 28(1):22-26.

Hamilton, M. T., D. G. Hamilton, and T. W. Zderic. 2007. Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes 56(11):2655-2667.

Hankinson, A. L., M. L. Daviglus, C. Bouchard, M. Carnethon, C. E. Lewis, P. J. Schreiner, K. Liu, and S. Sydney. 2010. Maintaining a high physical activity level over 20 years and weight gain. Journal of the American Medical Association 304(23): 2603-2610.

Hannon, J. C., and B. B. Brown. 2008. Increasing preschoolers’ physical activity intensities: An activity-friendly preschool playground intervention. Preventive Medicine 46(6): 532-536.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2008a. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/default.aspx (accessed October 20, 2010).

HHS. 2008b. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report 2008. http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/committeereport.aspx (accessed October 21, 2010).

HHS. 2010. The Surgeon General’s Vision for a Healthy and Fit Nation. Rockville, MD: HHS.

Hu, F. B., T. Y. Li, G. A. Colditz, W. C. Willett, and J. E. Manson. 2003. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. Journal of the American Medical Association 289(14):1785-1791.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2005. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM and NRC (National Research Council). 2009. Local Government Actions to Prevent Childhood Obesity Balance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jackson, D. M., K. Djafarian, J. Stewart, and J. R. Speakman. 2009. Increased television viewing is associated with elevated body fatness but not with lower total energy expenditure in children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 89(4):1031-1036.

Jago, R., T. Baranowski, J. C. Baranowski, D. Thompson, and K. A. Greaves. 2005. BMI from 3-6 y of age is predicted by TV viewing and physical activity, not diet. International Journal of Obesity 29(6):557-564.

Janz, K. F., S. M. Levy, T. L. Burns, J. C. Torner, M. C. Willing, and J. J. Warren. 2002. Fatness, physical activity, and television viewing in children during the adiposity rebound period: The Iowa bone development study. Preventive Medicine 35(6): 563-571.

Janz, K. F., T. L. Burns, and S. M. Levy. 2005. Tracking of activity and sedentary behaviors in childhood: The Iowa Bone Development Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 29(3):171-178.

Janz, K. F., S. Kwon, E. M. Letuchy, J. M. Eichenberger Gilmore, T. L. Burns, J. C. Torner, M. C. Willing, and S. M. Levy. 2009. Sustained effect of early physical activity on body fat mass in older children. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 37(1):35-40.

Jennings, J. T., B. G. Sarbaugh, and N. S. Payne. 2005. Conveying the message about optimal infant positions. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics 25(3):3-18.

Kaczynskl, A. T., and K. A. Henderson. 2008. Parks and recreation settings and active living: A review of associations with physical activity function and intensity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 5(4):619-632.

Kelly, L. A., J. J. Reilly, D. M. Jackson, C. Montgomery, S. Grant, and J. Y. Paton. 2007. Tracking physical activity and sedentary behavior in young children. Pediatric Exercise Science 19(1):51-60.

Klesges, R. C., L. H. Eck, C. L. Hanson, C. K. Haddock, and L. M. Klesges. 1990. Effects of obesity, social interactions, and physical environment on physical activity in preschoolers. Health Psychology 9(4):435-449.

Klohe-Lehman, D. M., J. Freeland-Graves, K. K. Clarke, G. Cai, V. S. Voruganti, T. J. Milani, H. J. Nuss, J. M. Proffitt, and T. M. Bohman. 2007. Low-income, overweight and obese mothers as agents of change to improve food choices, fat habits, and physical activity in their 1-to-3-year-old children. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 26(3):196-208.

Kordestani, R. K., and J. Panchal. 2006. Neurodevelopment delays in children with deformational plagiocephaly. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 118(3):808-809; author reply 809-810.

Kuo, Y. L., H. F. Liao, P. C. Chen, W. S. Hsieh, and A. W. Hwang. 2008. The influence of wakeful prone positioning on motor development during the early life. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP 29(5):367-376.

Li, R., L. O’Connor, D. Buckley, and B. Specker. 1995. Relation of activity levels to body fat in infants 6 to 12 months of age. Journal of Pediatrics 126(3):353-357.

Maher, C. A., M. T. Williams, T. Olds, and A. E. Lane. 2007. Physical and sedentary activity in adolescents with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 49(6):450-457.

McKinney, C. M., M. L. Cunningham, V. L. Holt, B. Leroux, and J. R. Starr. 2009. A case-control study of infant, maternal and perinatal characteristics associated with deformational plagiocephaly. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 23(4):332-345.

McWilliams, C., S. C. Ball, S. E. Benjamin, D. Hales, A. Vaughn, and D. S. Ward. 2009. Best-practice guidelines for physical activity at child care. Pediatrics 124(6):1650-1659.

Metcalfe, J. S., and J. E. Clark. 2000. Sensory information affords exploration of posture in newly walking infants and toddlers. Infant Behavior and Development 23(3-4): 391-405.

Mildred, J., K. Beard, A. Dallwitz, and J. Unwin. 1995. Play position is influenced by knowledge of SIDS sleep position recommendations. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 31(6):499-502.

Mond, J. M., H. Stich, P. J. Hay, A. Kraemer, and B. T. Baune. 2007. Associations between obesity and developmental functioning in pre-school children: A population-based study. International Journal of Obesity 31(7):1068-1073.

Montgomery, C., J. J. Reilly, D. M. Jackson, L. A. Kelly, C. Slater, J. Y. Paton, and S. Grant. 2004. Relation between physical activity and energy expenditure in a representative sample of young children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 80(3):591-596.

Moore, L. L., D. Gao, M. L. Bradlee, L. A. Cupples, A. Sundarajan-Ramamurti, M. H. Proctor, M. Y. Hood, M. R. Singer, and R. C. Ellison. 2003. Does early physical activity predict body fat change throughout childhood? Preventive Medicine 37(1):10-17.

NASPE (National Association for Sport and Physical Education). 2009. Active Start: A Statement of Physical Activity Guidelines for Children from Birth to Age 5, 2nd ed. Reston, VA: NASPE.

Ogden, C. L., M. D. Carroll, L. R. Curtin, M. M. Lamb, and K. M. Flegal. 2010. Prevalence of high body mass index in U.S. children and adolescents, 2007-2008. Journal of the American Medical Association 303(3):242-249.

Okely, A. D., M. L. Booth, and T. Chey. 2004. Relationships between body composition and fundamental movement skills among children and adolescents. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 75(3):238-247.

Oliver, M., G. M. Schofield, and G. S. Kolt. 2007. Physical activity in preschoolers: Understanding prevalence and measurement issues. Sports Medicine 37(12):1045-1070.

Pate, R. R., M. J. Almeida, K. L. McIver, K. A. Pfeiffer, and M. Dowda. 2006. Validation and calibration of an accelerometer in preschool children. Obesity 14(11):2000-2006.

Pfeiffer, K. A., M. Dowda, K. L. McIver, and R. R. Pate. 2009. Factors related to objectively measured physical activity in preschool children. Pediatric Exercise Science 21(2):196-208.

Preiser, W. F. E., and E. Ostroff, eds. 2001. Universal Design Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Proctor, M. H., L. L. Moore, D. Gao, L. A. Cupples, M. L. Bradlee, M. Y. Hood, and R. C. Ellison. 2003. Television viewing and change in body fat from preschool to early adolescence: The Framingham Children’s Study. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders 27(7):827-833.

Reilly, J. J., J. Coyle, L. Kelly, G. Burke, S. Grant, and J. Y. Paton. 2003. An objective method for measurement of sedentary behavior in 3- to 4-year olds. Obesity Research 11(10):1155-1158.

Reilly, J. J., D. M. Jackson, C. Montgomery, L. A. Kelly, C. Slater, S. Grant, and J. Y. Paton. 2004. Total energy expenditure and physical activity in young Scottish children: Mixed longitudinal study. Lancet 363(9404):211-212.

Riddoch, C. J., S. D. Leary, A. R. Ness, S. N. Blair, K. Deere, C. Mattocks, A. Griffiths, G. Davey Smith, and K. Tilling. 2009. Prospective associations between objective measures of physical activity and fat mass in 12-14 year old children: The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). British Medical Journal 339:b4544.

Riley, B. B., J. H. Rimmer, E. Wang, and W. J. Schiller. 2008. A conceptual framework for improving the accessibility of fitness and recreation facilities for people with disabilities. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 5(1):158-168.

Rimmer, J. H., K. Yamaki, B. M. Lowry, E. Wang, and L. C. Vogel. 2010. Obesity and obesity-related secondary conditions in adolescents with intellectual/developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 54(9):787-794.

Robinson, S. 2010. Deformational plagiocephaly delays motor skill development in 6-month-old infants. Journal of Pediatrics 157(3):514-515.

Sääkslahti, A., P. Numminen, P. Salo, J. Tuominen, H. Helenius, and I. Välimäki. 2004. Effects of a three-year intervention on children’s physical activity from age 4 to 7. Pediatric Exercise Science 16(2):167-180.

Saelens, B. E., L. D. Frank, C. Auffrey, R. C. Whitaker, H. L. Burdette, and N. Colabianchi. 2006. Measuring physical environments of parks and playgrounds: EAPRS instrument development and inter-rater reliability. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 3(Suppl. 1):S190-S207.

Sallis, J. F., P. R. Nader, S. L. Broyles, C. C. Berry, J. P. Elder, T. L. McKenzie, and J. A. Nelson. 1993. Correlates of physical activity at home in Mexican-American and Anglo-American preschool children. Health Psychology 12(5):390-398.

Shibli, R., L. Rubin, H. Akons, and R. Shaoul. 2008. Morbidity of overweight (≥85th percentile) in the first 2 years of life. Pediatrics 122(2):267-272.

Sirard, J. R., S. G. Trost, K. A. Pfeiffer, M. Dowda, and R. R. Pate. 2005. Calibration and evaluation of an objective measure of physical activity in preschool children. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2(3):345-357.

Slining, M., L. S. Adair, B. D. Goldman, J. B. Borja, and M. Bentley. 2010. Infant overweight is associated with delayed motor development. Journal of Pediatrics 157(1):20-25 e21.

Steele, C., I. Kalnins, J. Jutai, J. Bortolussi, and W. Biggar. 1996. Lifestyle health behaviours of 11- to 16-year-old youth with physical disabilities. Health Education Research 11:173-186.

Strong, W. B., R. M. Malina, C. J. Blimkie, S. R. Daniels, R. K. Dishman, B. Gutin, A. C. Hergenroeder, A. Must, P. A. Nixon, J. M. Pivarnik, T. Rowland, S. Trost, and F. Trudeau. 2005. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. Journal of Pediatrics 146(6):732-737.

Thein, M., J. Lee, V. Tay, and S. Ling. 1997. Infant walker use, injuries and motor development. Injury Prevention 3:63-66.

Trost, S. G., B. Fees, and D. Dzewaltowski. 2008. Feasibility and efficacy of a “move and learn” physical activity curriculum in preschool children. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 5(1):88-103.

Trost, S. G., D. S. Ward, and M. Senso. 2010. Effects of child care policy and environment on physical activity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 42(3): 520-525.

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) and HHS. 2010. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010. http://www.healthierus.gov/dietaryguidelines (accessed January 12, 2011).

Ward, D. S., S. E. Benjamin, A. S. Ammerman, S. C. Ball, B. H. Neelon, and S. I. Bangdiwala. 2008. Nutrition and physical activity in child care. Results from an environmental intervention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35(4): 352-356.

Ward, D. S., A. Vaughn, C. McWilliams, and D. Hales. 2010. Interventions for increasing physical activity at child care. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 42(3):526-534.

Wells, J. C., T. J. Cole, and P. S. Davies. 1996a. Total energy expenditure and body composition in early infancy. Archives of Disease in Childhood 75(5):423-426.

Wells, J. C., M. Stanley, A. S. Laidlaw, J. M. Day, and P. S. Davies. 1996b. The relationship between components of infant energy expenditure and childhood body fatness. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders 20(9):848-853.

Williams, C. L., B. J. Carter, D. L. Kibbe, and D. Dennison. 2009. Increasing physical activity in preschool: A pilot study to evaluate animal trackers. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 41(1):47-52.

Williams, H., and E. Monsma. 2007. Assessment of gross motor development in preschool children. In The Psychoeducational Assessment of Preschool Children, edited by B. N. Bracken. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.