I have a master’s degree in clinical social work. I have a well-documented illness that explains the cause of my pain. But when my pain flares up and I go to the ER, I’ll put on the hospital gown and lose my social status and my identity. I’ll become a blank slate for the doctors to project their own biases and prejudices onto. That is the worst part of being a pain patient. It strips you of your dignity and self-worth.

—A patient with chronic pain2

Approximately 100 million U.S. adults—more than the number affected by heart disease, diabetes, and cancer combined—suffer from common chronic pain conditions (Tsang et al., 2008; see also Appendix C). Everyone is at some risk of acute or chronic pain arising from an illness, an injury, or an array of other factors, but some population groups have a much higher risk of experiencing pain and its disabling effects and receiving inadequate treatment.

Pain is a universal experience but unique to each individual. Across the life span, pain—acute and chronic—is one of the most frequent reasons for

________________

1 The quotations throughout this report come from the committee’s survey on pain care, testimony received at public workshops, committee member comments, and published sources, as noted. Survey responses were submitted January 31, 2011 through April 5, 2011. See Appendix B for a description of the survey.

2 Quotation from committee survey.

physician visits, among the most common reasons for taking medications, and a major cause of work disability. Severe chronic pain affects physical and mental functioning, quality of life, and productivity. It imposes a significant financial burden on affected individuals, as well as their families, their employers, their friends, their communities, and the nation as a whole. The annual economic cost of chronic pain in adults, including health care expenses and lost productivity, is $560-630 billion annually according to a new estimate developed for this study (see Appendix C).

STUDY CONTEXT AND CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

Section 4305 of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act required the Secretary, Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), to enter into an agreement with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) for activities “to increase the recognition of pain as a significant public health problem in the United States.” Accordingly, HHS, through the National Institutes of Health (NIH), requested that the IOM conduct a study to assess the state of the science regarding pain research, care, and education and to make recommendations to advance the field. The charge to the committee is presented in Box 1-1.

To conduct this study, the IOM assembled a 19-member committee, which began meeting in November 2010. Reflecting the complexity of the problem at hand, the committee included experts in pain research, pain management, pharmacology, clinical specialties (pediatrics, oncology, infectious disease, neurology, neurosurgery, anesthesiology, pain medicine, dentistry, psychology, and complementary medicine), chronic disease, clinical teaching, epidemiology, ethics, and consumer education, as well as individuals who have suffered personally from chronic pain and could reflect on the perspectives of the many people it affects.

STUDY APPROACH AND UNDERLYING PRINCIPLES

The challenges to better pain management in the United States are diverse. Some result from inadequate scientific knowledge about diagnosis and treatment and may be resolved by new research. Many of the challenges, however—those related to inadequate training and lack of understanding of the need to address the multiple physical, mental, emotional, and social dimensions of pain; to disparities in care among population groups; and to payment and policy barriers—reflect a failure to apply what is already known.

This report makes an important contribution to the field by providing a blueprint for transforming the way pain is understood, assessed, treated, and prevented. It provides recommendations for improving the care of people who experience pain, the training of clinicians who treat them, and the collection of data on pain in the United States, as well as a timetable for implementing measures to better relieve pain in America. The committee also recommends ways

BOX 1-1

Committee Charge

The Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, has requested that the IOM convene the ad hoc committee to address the current state of the science with respect to pain research, care, and education; and explore approaches to advance the field.

Specifically, the committee will

- Review and quantify the public health significance of pain, including the adequacy of assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and management of acute and chronic pain in the United States. This effort will take a comprehensive view of chronic pain as a biological, biobehavioral, and societal condition.

- Identify barriers to appropriate pain care and strategies to reduce such barriers, including exploring the importance of individualized approaches to diagnosis and treatment of pain.

- Identify demographic groups and special populations, including older adults, individuals with co-morbidities, and cognitive impairment, that may be disparately undertreated for pain, and discuss related research needs, barriers particularly associated with these demographic groups, and opportunities to reduce such barriers.

- Identify and discuss what scientific tools and technologies are available, what strategies can be employed to enhance training of pain researchers, and what interdisciplinary research approaches will be necessary in the short and long term to advance basic, translational, and clinical pain research and improve the assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and management of pain.

- Discuss opportunities for public–private partnerships in the support and conduct of pain research, care, and education.

to help focus research and policy directives on a variety of dimensions of pain. The report does not present a clinical algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with pain. Rather, it describes the scope of the problem of pain and provides an overview of needs for care, education, and research. The committee strongly believes that an adequate understanding of pain and its effects on people’s lives must take into account the testimony of those who have experienced chronic pain. Therefore, it solicited advice and information from people with pain and their advocates both in person and through an active web portal, which received more than 2,000 submissions. The committee’s recommendations are based on scientific evidence, on this wealth of direct testimony, and on the expert judgment of its members (see Appendix A for a discussion of the data sources and methods for this study). Underlying principles that guided the committee in preparing this report and its recommendations are presented in Box 1-2.

BOX 1-2

Underlying Principles

- A moral imperative. Effective pain management is a moral imperative, a professional responsibility, and the duty of people in the healing professions.

- Chronic pain can be a disease in itself. Chronic pain has a distinct pathology, causing changes throughout the nervous system that often worsen over time. It has significant psychological and cognitive correlates and can constitute a serious, separate disease entity.

- Value of comprehensive treatment. Pain results from a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors and often requires comprehensive approaches to prevention and management.

- Need for interdisciplinary approaches. Given chronic pain’s diverse effects, interdisciplinary assessment and treatment may produce the best results for people with the most severe and persistent pain problems.

- Importance of prevention. Chronic pain has such severe impacts on all aspects of the lives of its sufferers that every effort should be made to achieve both primary prevention (e.g., in surgery for a broken hip) and secondary prevention (of the transition from the acute to the chronic state) through early intervention.

- Wider use of existing knowledge. While there is much more to be learned about pain and its treatment, even existing knowledge is not always used effectively, and thus substantial numbers of people suffer unnecessarily.

- The conundrum of opioids. The committee recognizes the serious problem of diversion and abuse of opioid drugs, as well as questions about their long-term usefulness. However, the committee believes that when opioids are used as prescribed and appropriately monitored, they can be safe and effective, especially for acute, postoperative, and procedural pain, as well as for patients near the end of life who desire more pain relief.

- Roles for patients and clinicians. The effectiveness of pain treatments depends greatly on the strength of the clinician–patient relationship; pain treatment is never about the clinician’s intervention alone, but about the clinician and patient (and family) working together.

- Value of a public health- and community-based approach. Many features of the problem of pain lend themselves to public health approaches—concern about the large number of people affected, disparities in occurrence and treatment, and the goal of prevention cited above. Public health education can help counter the myths, misunderstandings, stereotypes, and stigma that hinder better care.

In general, the committee considered the complexities of individual pain conditions and the diseases that cause pain—which vary widely in their presentation, treatment, effects, and outcomes—to be beyond the scope of this study. Nor did the study address the important issue of psychological or existential pain that exacerbates many experiences of pain. A much larger study would be necessary

to address these issues. Similarly, a deep examination of the current controversies surrounding opioid abuse and diversion were beyond the committee’s charge. The committee recognizes that as a result, many of the generalizations included in this report will not apply equally well to all pain conditions, although the overall direction and priorities of the report should be broadly useful.

The findings and recommendations presented in this report are intended to assist policy makers, federal agencies, state public health officials, health care providers (primary care clinicians and pain specialists), health care organizations, health professions associations, pain researchers, individuals living with pain and their families, the public, and private health funding organizations in addressing the problem of pain. The ultimate goal of this study is to contribute to improved outcomes for individuals who experience pain and their families.

This report builds on and reinforces recommendations regarding ways to improve pain care, education, and research—and the research enterprise in general—made by the IOM in past reports, as well as by other entities. As it conducted this study, the committee generally saw little evidence of progress toward these well-articulated goals and extensively documented findings of the past. Examples of such reports include

- Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life (IOM, 1997);

- Ensuring Quality Cancer Care (IOM, 1999);

- Pain and Disability: Clinical, Behavioral, and Public Policy Perspectives (IOM, 1987);

- A Call to Revolutionize Chronic Pain Care in America: An Opportunity in Health Reform (The Mayday Fund, 2009);

- New Approaches to Neurological Pain: Planning for the Future (Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and University of California, San Francisco, 2008);

- Pain, Depression, and Fatigue: State-of-the-Science Conference (NIH, 2002);

- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: State-of-the-Science Conference (NIH, 2000);

- The First National Pain Medicine Summit: Final Summary Report (American Medical Association Specialty Section Council, 2010);

- Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (IOM, 2003);

- Transforming Clinical Research in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities (IOM, 2010); and

- Enhancing the Vitality of the National Institutes of Health: Organizational Change to Meet New Challenges (NRC and IOM, 2003).

The committee hopes that this report will have an impact on the important challenge of pain, given its impact on the lives of more than a third of Americans and the economic well-being of the nation.

It is so much more than just pain intensity. Over time, many [patients] find the effects of living with chronic pain impact their ability to work, engage in recreational and social activities, and for some, [perform] the most basic everyday activities that people just take for granted. Not surprisingly, pain begins to chip away at their mood, often leaving them angry, frustrated, anxious, and/or depressed. Our families suffer along with us, and many relationships are forever altered.

—An advocate for people with chronic pain3

There is no visible blood test or X ray to show a trauma. I do not look sick.

—A person with chronic pain4

Pain is a warning, a signal that something is wrong, whether it is caused by a stove too hot to touch, a broken arm, an attack of angina, or a bout of food poisoning. In its warning role, pain is protective and sometimes even essential for survival. Its aversive quality motivates individuals to do something—to withdraw or flee, to seek help or rest or medical treatment. The reaction to a painful stimulus occurs at a deep evolutionary level and is powerfully protective. Without pain, the world would be an impossibly dangerous place. For example, some children with a rare genetic disease are born with the inability to feel pain. At first thought, these children might appear to be fortunate, but they typically have a short life span because they do not realize when they are injured or sick, and they succumb to early arthritis, wounds, and infections that children without this disease avoid.

Pain is a complex phenomenon. The unique way each individual perceives pain and its severity, how it evolves, and the effectiveness of treatment depend on a constellation of biological, psychological, and social factors, such as the following:

- Biological—the extent of an illness or injury and whether the person has other illnesses, is under stress, or has specific genes or predisposing factors that affect pain tolerance or thresholds;

________________

3 Quotation from committee survey.

4 Quotation from committee survey.

- Psychological—anxiety, fear, guilt, anger, depression, and thinking the pain represents something worse than it does and that the person is helpless to manage it (Ochsner et al., 2006); and

- Social—the response of significant others to the pain—whether support, criticism, enabling behavior, or withdrawal—the demands of the work environment, access to medical care, culture, and family attitudes and beliefs.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) published its widely accepted definition of pain in 1994, excerpted in Box 1-3. This useful definition has been influential in replacing earlier views that pain is strictly a physical, or biological, problem because it takes into account that emotional and psychosocial reactions to pain are clinically significant.

Most chronic diseases involve multiple physical, cognitive, and emotional factors. While chronic pain shares many attributes with other chronic diseases, it also has distinct characteristics. For example, pain, especially chronic pain, can lack reliable “objective” measures, and it has strong cultural, religious, and philosophical meanings that affect (and serve as context for) a person’s pain experience. Because all people experience some degree of pain at some time, moreover, they often do not realize how chronic severe pain differs in its character and effects from the relatively mild and easily treated pain with which they are familiar.

The IASP definition emphasizes that pain is a subjective experience. Other people cannot detect a person’s pain through their own senses: it cannot be seen, like bleeding; it cannot be felt, like a lump; it cannot be heard, like a heart arrhythmia; it has no taste or odor; and it often is not confirmed by x-ray or more sophisticated imaging procedures. No current clinical tests for pain are analogous to temperature, blood pressure, or cholesterol measurements. Clinical findings that can be seen—a broken bone on an x-ray, for example—do not necessarily correlate well with the severity of pain the patient perceives. People afflicted by pain may find the rough tools of language inadequate to convey the character and

BOX 1-3

Definition of Pain

An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage. … Pain is always subjective. … It is unquestionably a sensation in a part or parts of the body, but it is also always unpleasant and therefore also an emotional experience.

SOURCE: IASP, 1994.

intensity of their experience and its significance to them. This can be a substantial barrier to obtaining adequate treatment (Werner and Malterud, 2003).

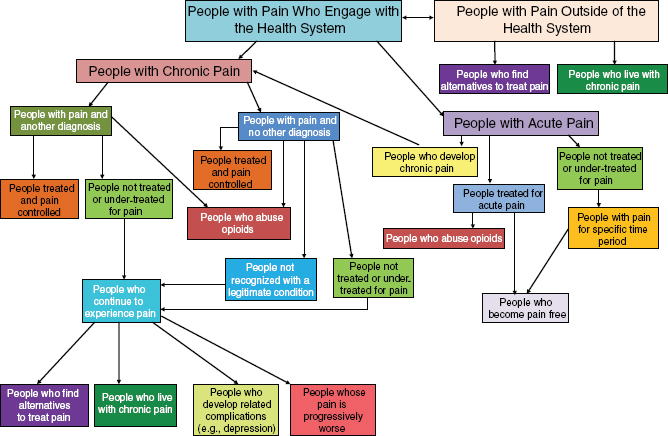

Figure 1-1 shows the many branching pathways pain can take. On the right side are the pathways for acute pain, one branch of which moves a person to the left side of the figure, which illustrates the erratic course of chronic pain. The figure shows that pain may be treated and controlled at a number of points in a person’s experience, but also that it may persist, loop back on itself, engender related complications, and prompt an ongoing search for relief.

Pain sensation, transmission, modulation, and interpretation are functions of the central nervous system, and when abnormalities in this process occur, pain can be a neurologic disease. Increased understanding of the many physiological and psychological changes that occur in people with chronic pain has prompted the IASP and many pain experts to deem that in many cases, chronic pain is a disease in its own right (EFIC, 2001), a position supported by this committee.

This profound recasting means that pain requires direct, appropriate treatment rather than being sidelined while clinicians attempt to identify some underlying condition that may have caused it. Prompt treatment can derail the progression of pain from the acute to the chronic state. This recasting also means that health professions education programs should include a substantial amount of learning about pain and its diversity, and that people with chronic pain should be recognized by family, employers, health insurers, and others as having a serious disease. It means that people with chronic pain have an important role to play in managing their disease in an informed, productive way. And finally, it means that the research community should pursue pain research with the same vigor expended on other serious and disabling chronic conditions.

Thirteen years ago I was rear-ended in a car accident. In a split second my whole life changed, and the accident left me handicapped with chronic pain in the neck, shoulders, and head. I was thrown into a world of medical decisions of which I knew nothing and began searching for information about cervical discs, facet joints, myofascial pain, referred pain, conservative and alternative treatments and various medical procedures. …

— A patient with chronic pain5

________________

5 Quotation from public testimony submitted by the American Pain Society.

Information about the number of people who have acute or chronic pain is far from complete. Nevertheless, as Box 1-4 illustrates, pain is pervasive and costly, and it is associated with common events and conditions, such as surgery, trauma, cancer, arthritis, migraine, and fibromyalgia, that involve large numbers of Americans (Box 1-5). Pain is common in settings such as nursing homes and other long-term care facilities. Furthermore, people who experience acute pain may go on to develop chronic, intractable pain.

BOX 1-4

Pain by the Numbers

• 100 million—approximate number of U.S. adults with common chronic pain conditions

• $560 to 635 billion—conservative estimate of the annual cost of chronic pain in America

• $99 billion—2008 cost to federal and state governments of medical expenditures for pain

• 60 percent—percentage of women experiencing their first childbirth who rate pain as severe; 18 percent of women who have caesarean deliveries and 10 percent who have vaginal deliveries report persistent pain at 1 year

• 80 percent—percentage of patients undergoing surgery who experience postoperative pain; fewer than half report adequate pain relief:

— of these, 88 percent report the pain is moderate, severe, or extreme;

— 10 to 50 percent of patients with postsurgical pain develop chronic pain, depending on the type of surgery; and

— for 2 to 10 percent of these patients, this chronic postoperative pain is severe

• 5 percent—proportion of American women aged 18 to 65 who experience headache 15 or more days per month over the course of 1 year

• 60 percent—percentage of patients visiting the emergency department with acute painful conditions who receive analgesics:

— median time to receipt of pain medication is 90 minutes, and

— 74 percent of emergency department patients are discharged in moderate to severe pain

• 2.1 million—number of annual visits to U.S. emergency departments for acute headache (of 115 million total annual visits)

• 62 percent—percentage of U.S. nursing home residents who report pain:

— arthritis is the most common painful condition, and

— 17 percent have substantial daily pain

• 26.4 percent—percentage of Americans who report low back pain lasting at least a day in the last 3 months

SOURCES: (Costs) Appendix C; (Childbirth) Melzack, 1993; Kainu et al., 2010; (Surgery) Apfelbaum et al., 2003; Kehlet et al., 2006; (Headache) Scher et al., 1998; (Emergency care) Todd et al., 2007; (Emergency: headache) Edlow et al., 2008; (Nursing homes) Ferrell et al., 1995; Sawyer et al., 2007; (Low back pain) Deyo et al., 2006.

BOX 1-5

Selected Pain-Related Conditions

Common sources of acute pain

• infectious diseases (e.g., food poisoning with related gastrointestinal manifestations)

• wound infections

• untreated dental conditions

• burns

• trauma (broken bones, lacerations and other wounds)

• appendicitis

• surgery

• medical procedures

• childbirth

Common sources of chronic pain

• migraine and other serious headaches

• arthritis and other joint pain

• fibromyalgia

• endometriosis

• irritable bowel syndrome

• chronic interstitial cystitis

• vulvodynia

• trauma or postsurgical pain

• low back pain

• other musculoskeletal disorders

• temporomandibular joint disorder

• shingles

• sickle cell disease

• heart disease (angina)

• cancer

• stroke

• diabetes

Taken together, the available data suggest that all Americans have a significant chance of experiencing serious pain. Subsequent chapters of this report demonstrate that much of this pain and the attendant suffering are unnecessary and could be prevented or better managed.

The risk of both acute and chronic pain is affected by many factors, including age, race, sex, income, education, urban/rural living, and other demographic factors reviewed in Chapter 2. The likelihood of experiencing a transition from acute to chronic pain is likewise influenced by various factors, especially the adequacy of acute pain relief. The factors that influence the development of chronic pain can be assessed using a life-cycle approach (see Table 1-1). Some factors

TABLE 1-1 Life-Cycle Factors Associated with the Development of Chronic Pain*

| From Birth | Childhood | Adolescence | Adulthood | ||||||||||||||||

|

Genetics, female sex, minority race or ethnicity, congenital disorders, prematurity Parental anxiety, irregular feeding and sleeping |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Parents’ pain exposure and reactions Temperament and personality |

Physical/sexual abuse and other traumatic events (e.g., death of a parent, witness to violence) Low socioeconomic status Emotional, conduct, and peer problems Hyperactivity Serious illness or injury, hospitalization |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Separation from mother Acute or recurrent pain experience |

Changes of puberty, gender roles Education level, learning (behavioral reactions to pain) |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Injuries Obesity Low levels of fitness |

Vivid recall of childhood trauma Lack of social support, accumulated stress (“allostatic load”) Surgery Overuse of joints and muscles Occupational exposures, job dissatisfaction, low work status Development of chronic disease Aging |

||||||||||||||||||

*NOTE: These factors are discussed later in this chapter and in Chapter 2.

are present from birth, some occur in childhood or adolescence, and some may not appear until later in life. And some people with many of the risk factors listed never develop chronic pain. Ways in which these factors contribute to higher rates of pain and associated disability are discussed in Chapter 2.

As part of an orientation toward prevention, both protective and risk factors for chronic pain need to be better characterized. Examples of protective factors include engaging in moderate physical activity, controlling weight, avoiding injuries, receiving pre- and postsurgical analgesia6 and monitoring, and having personality traits such as resilience and positive affect. With respect to risk factors, it is important to understand that some of the factors listed in Table 1-1 clearly cannot be modified. For example, knowing that there are immutable factors (such as gender differences) in the susceptibility to chronic pain syndromes should lead to earlier intervention when acute pain occurs and greater efforts to avoid or reduce the influence of other risk factors.

IMPACT OF PAIN ON PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH

It made no sense to me that with all the modern miracles in medicine there was no way to relieve my pain. What I did not realize then was how complex chronic pain is. I did not know how many areas of my life and my family’s lives the pain invaded.

— An advocate for people with chronic pain7

Although much acute and milder chronic pain is managed by people on their own or with the guidance of health professionals, severe and intractable pain may require comprehensive approaches that take into account the biological, psychological, and social factors noted previously. While many people ultimately may have their pain controlled, some will not, and repeated attempts may be required to find the right combination of therapies and self-care to achieve maximum benefit.

Understanding of the mechanisms underlying pain has changed over time and will continue to evolve with new knowledge. Research has now established that pain can cause biological changes in the peripheral and central nervous systems, as described later in this chapter. While some of these changes are adaptive and of short duration, they can become maladaptive and signal the development of chronic pain, in which case the central nervous system becomes hypersensitive and overresponsive to stimuli that normally would not be painful—a light touch

________________

6Boldface terms in this chapter are included in the glossary at the end of the report.

7 Quotation from committee survey.

or a gentle breeze, for example. In a sense, the nervous system of a person with chronic pain becomes “rewired for pain.”

Among the immediate consequences of severe pain, aside from the hurt itself, are “reduced mobility and consequent loss of strength, disturbed sleep, immune impairment and increased susceptibility to disease, dependence on medication, and codependence with solicitous family members and other caregivers” (Brennan et al., 2007). The consequences of acute pain add to the preceding list the following: reduced quality of life, impaired physical function, high economic costs (principally hospital readmissions), extended recovery time, and increased risk of developing chronic pain (Sinatra, 2010). In addition to an array of physical problems, severe chronic pain can engender a range of significant psychological and social consequences, such as fear; anger; depression; anxiety; and reduced ability to carry out one’s social roles as family member, friend, and employee. At the same time, as knowledge about the biological processes of pain has advanced, a large, broad, and growing empirical literature has continued to inform the increasingly sophisticated understanding of key psychological and behavioral factors that influence the perpetuation, if not the development, of pain and pain-related disability. The complex relationship between pain and these factors is discussed in detail later in the chapter.

When they refused to treat me at the emergency room, they said, “We can’t treat you for pain because we would be treating a symptom rather than the cause of a problem.”

— A person with chronic pain8

Pain is more than a symptom!

— A physician who treats chronic pain9

Pain comes in many forms. Understanding which kind or kinds of pain a person has is a first step toward treatment. Although acute and chronic pain are considered separately below, a particular individual can experience them simultaneously.

________________

8 Quotation from submission by Peter Reineke of stories from the membership of patient advocacy groups.

9 Quotation from committee member.

Acute pain, by definition, is of sudden onset and expected to last a short time. It usually can be linked clearly to a specific event, injury, or illness—a muscle strain, a severe sunburn, a kidney stone, or pleurisy, for example. People can handle many types of acute pain on their own with over-the-counter medications or a short course of stronger analgesics and rest, and the acute pain usually subsides when the underlying cause resolves, such as when a kidney stone or diseased tooth is removed. Acute pain also can be a recurrent problem, with episodes being interspersed with pain-free periods, as in the case of dysmenorrhea, migraine, and sickle-cell disease.

Chronic pain, by contrast, lasts more than several months (variously defined as 3 to 6 months, but certainly longer than “normal healing”) and can be frustratingly difficult to treat. Although improvement may be possible, for many patients cure may be unlikely. Chronic pain can become so debilitating that it affects every aspect of a person’s life—the ability to work, go to school, perform common tasks, maintain friendships and family relationships—essentially, to participate in the fundamental tasks and pleasures of daily living. Chronic pain can be the result of

• An underlying disease or medical condition, in which case,

— it may continue or recur after the disease itself has been cured, as in shingles;

— it may simply not go away, and flare-ups may occur against a background of persistent pain, as in many instances of low back pain or osteoarthritis; or

— it may worsen as the disease (such as cancer) progresses.

• An injury, if the pain persists after the original injury heals—for example, “phantom limb” or “phantom tooth” pain, in which a person continues to feel pain in an amputated limb or missing tooth.

• Medical treatment, for example, after surgery, when the typical immediate acute pain, if unresolved, evolves into chronic pain or if nerve damage occurs during a procedure.

• Inflammation, in which pain occurs in response to tissue injury, when local nociceptors become highly sensitive even to normal stimuli, such as touch. (This is a form of peripheral sensitization. The overexcitement of neurons in the central nervous system is central sensitization and can occur with any type of pain.) This is another type of “warning” pain, this time of the need for healing, and generally disappears after the injury resolves. In conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or gout, inflammatory pain persists as long as the inflammation does.

• Neuropathic pain, a disease of the peripheral or central nervous system that arises when a person’s nerves, spinal cord, or brain is damaged or fails to function properly for any of a large number of reasons. The cause may be an underlying disease process (as in diabetes) or injury

(e.g., stroke, spinal cord damage), but neuropathic pain may not have an observable cause and can be considered maladaptive “in the sense that the pain neither protects nor supports healing and repair” (Costigan et al., 2009, p. 3).

• Unknown causes, in which case the pain arises without a defined cause or injury. Examples of such chronic pain conditions are irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, vulvodynia, chronic headaches, and temporomandibular disorders. For some disorders, research points to impaired central pain sensitivity and responses in these conditions, but their complex mechanisms have not yet been unraveled (Kindler et al., 2011).

WHAT CAUSES PAIN, AND WHY DOES IT SOMETIMES PERSIST?

Even with limitless resources, not every patient’s pain can be eliminated

—Brennan et al., 2007

The following brief summary of the rapidly evolving body of research on pain—a subject with a deep literature in many disciplines—is not intended to be comprehensive. Rather, its purpose is to help readers understand the discussion in subsequent chapters of the impact of chronic pain on people’s lives and the challenges of providing better pain care.

The Complexity of Chronic Pain

Treating a pain patient can be like fixing a car with four flat tires. You cannot just inflate one tire and expect a good result. You must work on all four.

—Penny Cowan, American Chronic Pain Association, an advocate for people with chronic pain10

In the past several decades, the long-standing belief regarding the strict separation between mind and body, often attributed to the early 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes, has given way to an appreciation of the interdependency between mind and body in health, illness, and disease and

________________

10 Quotation from oral testimony to the committee.

the even broader perspective that recognizes the influence of the social environment (Marmor et al., 1994). If the Cartesian model of mind–body separation were correct, pain would be “restricted to the injury site and should be abolished after healing” (Kuner, 2010, p. 1258). Yet personal experiences, reports of clinicians who treat people with pain, and scientific research on the way pain alters the brain and nervous system indicate otherwise. A strictly biomedical approach to pain is simply too reductionist; rather, what is called for is an approach that recognizes the complexity of the pain experience. Similar to what has been learned about other chronic diseases, chronic pain ultimately affects (and is affected by) many intrinsic and extrinsic aspects of a person’s life. Today, most researchers and clinicians who specialize in pain issues use the “biopsychosocial model” (denoting the combination of biological, psychological, and social/family/cultural contexts of pain) to understand and treat chronic pain (Gatchel et al., 2007).

In general, the early theories of how pain works failed to address key issues, many of which were described a number of years ago by Melzack and Wall (1996):

- The relationship between injury and pain varies (that is, a minor injury may produce great pain, or a significant injury may produce minor pain), as does the relationship between the extent of injury and the resulting disability.

- Non-noxious stimuli can sometimes produce pain (allodynia), and minor amounts of noxious stimuli can produce large amounts of pain (hyperalgesia).

- The locations of pain and tissue damage are sometimes different (referred pain).

- Pain can persist long after tissue healing.

- The nature of pain and sometimes its location can change over time.

- Pain is a multidimensional experience, with strong psychosocial influences and impacts.

- Responses to a given therapy vary among individuals.

- Earlier theories have not led to adequate pain treatments.

Over time, pain has become understood as a complex condition involving numerous areas of the brain; multiple two-way communication pathways in the central nervous system (from the site of pain to the brain and back again); and emotional, cognitive, and environmental elements—a complete, interconnected apparatus. In this sense, chronic pain resembles many other chronic diseases in that it has numerous interacting and contributing causes and multiple effects. This multiplicity of causes and effects opens up the possibility for a variety of treatment approaches. In severe chronic pain syndromes, quite a number of treatments may be attempted before the combination of physiological, cognitive, psychological, clinical, and self-care approaches that will produce the best result

for a specific person is identified. Sometimes a single clinician has the requisite skills to accomplish this, and sometimes a team is required. The determination of who should care for the person with pain and the settings where that care should occur has an impact on health care delivery, as well as patients’ health and well-being.

Genetic Influences

The way the central nervous system processes and transmits pain-related information can be influenced by a number of genetic factors. In general, these factors affect a person’s pain sensitivity either by increasing the transmission of nociception signals to the brain and sometimes hijacking additional nerves to do so, or by decreasing central inhibitory signals whose purpose is to dampen the pain response. (At times, genetic influences can work exactly the opposite way as well, decreasing nociception transmission and increasing inhibitory signals.) The body’s ability to release hormones, such as adrenalin (epinephrine), that stave off pain for a while is an important part of the basic “fight or flight” response. When adrenalin’s effects subside, a person feels exhausted, which signals the body to rest.

Genetic factors can work in other ways as well. For example, they can affect the survival of neurons and therefore the strength of the nociceptive response; they may be at least partly responsible for differences between men and women in pain perception, tolerance, and analgesic response; and they have been shown to affect individual responses to opioids, including the likelihood of addiction (Li et al., 2008).

Nociception involves multiple steps, each accomplished by many specific molecules, such as neurotransmitters and the enzymes involved in protein synthesis. Some of these molecules increase pain sensitivity, some inhibit it, and each of them is subject to over- or underproduction as a result of genetic influences. But all must be working together properly and in balance, in all the transmission steps, to ensure that the final signal to the brain (and back) is accurate. Although these reactions may begin with a genetic proclivity, what the individual learns from these experiences influences and often strengthens subsequent reactions, a subtle process that establishes the basis for increasing pain sensitization.

Only a few pain conditions are strongly associated with a single variation in the DNA sequence of a gene; most involve multiple “risk-conferring” genes (Costigan et al., 2009). Most studies suggest that many common pain disorders—such as migraine and various types of joint pain, including low back pain—have a strong inherited component (Kim and Dionne, 2005). Efforts such as those at the Pain Genetics Lab of McGill University are focused on describing how genetic makeup can explain individual differences in pain sensitivity, response to analgesia, and susceptibility to chronic pain conditions, as well as how genes and environmental factors interact in producing these effects.

As researchers continue to unravel the workings of genetically influenced pain mechanisms, the potential emerges for new approaches to screening for and treatment of chronic pain syndromes and better targeting of therapeutics—so-called “personalized medicine.” In addition, findings regarding these mechanisms may help explain why other factors, such as hormonal changes, can upset the body’s delicate chemical balance and alter an individual’s pain sensitivity over time.

Pain in Childhood

Researchers have studied for some time whether having pain in childhood influences the development of adult diseases and pain conditions, under the theory that the body’s cumulative efforts to adapt to acute stress (a person’s “allostatic load”) eventually harm various organs, tissues, and body systems. Establishing this link also helps explain how the stresses of growing up poor, poorly educated, or in stressful environments might produce the “gradients of morbidity and mortality that are seen across the full range of income and education referred to as SES [socioeconomic status] and which account for striking differences of health between rich and poor” (McEwen, 2000, p. 111).

Psychological stressors have been shown to increase the likelihood of developing a range of serious adult diseases that involve pain, including arthritis, diabetes, heart disease, and chronic pain itself. The concept of allostatic load could explain the higher rates of some of these diseases in adults who have had early exposure to abuse or violence (Nielsen et al., 2007). Across society, “unhealthy environments are those that threaten safety, that undermine the creation of social ties, and that are conflictual, abusive, or violent” (Taylor et al., 1997, p. 411). For example, adults who have faced multiple “adversities” or suffered from anxiety or depression in childhood have a statistically significant increase in the risk of developing arthritis (Von Korff et al., 2009).

Responses to pain (physical, emotional, and cognitive) are generally learned in childhood, and these learned responses are important in understanding how adults cope with persistent pain. For example, a study of children with recurrent abdominal pain suggests that those who learn unhealthy responses to chronic pain, reflected in somatic and emotional distress, are more likely to become adults with chronic pain (Walker et al., 1995; Macfarlane, 2010). Yet some individuals are more resilient than others in the face of early adversity. It remains a question whether genetic predisposition plays a factor in these differences, in which case we need a greater appreciation of the specific psychosocial attributes involved in health outcomes (Nielsen et al., 2007).

As will be reviewed in Chapter 2, pain is not uncommon and often is undertreated in children and adolescents. And certainly we have come a long way from the era in which infants were believed not to suffer pain and so were not provided anesthesia or other pain-prevention measures for surgery and medical procedures (Schechter et al., 2002).

Nerve Pathways

A frequently cited hypothesis that links all the various influences on pain, known as the “neuromatrix theory,” is that pain is “produced by the output of a widely distributed neural network” that is “genetically determined and modified by sensory experience” throughout life (Melzack, 2005, p. 1378). According to this theory, pain is the output of the neural network, and not “a direct response to sensory input following tissue injury, inflammation, and other pathologies” (Gatchel et al., 2007, p. 584). Although pain most often is triggered by such sensory inputs, it need not be.

The neuromatrix theory enables new thinking about chronic pain syndromes, such as fibromyalgia, that do not have an obvious cause but are associated with changes in the central nervous system. These changes are possible because the brain and nerves are not a fixed system but neuroplastic—that is, capable of adapting (in this case, in a negative way) at the level of the neuron; at the network level, where processing of pain inputs occurs; and at the structural level, which “can account for the long-term persistence of changes that arise in pathological pain states” (Kuner, 2010, p. 1259). Considerable progress has been made in the development of theories about the origins of pain, including the gate control theory, as well as in the development of new scientific knowledge, including the role of central sensitization. These advances have finally made it possible to begin to unravel the mechanisms of various chronic pain syndromes and phenomena such as phantom limb pain. The neuromatrix theory, not relying on direct sensory input, is especially important in this regard.

The Brain’s Role

Until recently, understanding of the mechanisms of pain generation and transmission from the spinal cord to the brain has been based primarily on studies using animal models. The recent introduction of increasingly sophisticated, noninvasive neuroimaging technologies has made the human central nervous system available for direct examination and comparison between healthy subjects and people with chronic pain. The ultimate goal is to use these neuroimaging techniques to develop more effective and safer approaches to pain management.

Several imaging techniques have been used to investigate pain, including:

- electrophysiological methods, such as the electroencephalogram (EEG) and magnetoencephalogram (MEG);

- radiological methods, such as positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computerized tomography; and

- magnetic resonance techniques, such as magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

These neuroimaging techniques can be categorized as structural (revealing anatomical information, e.g., MRI, DTI), biochemical (revealing information regarding the local chemical environment, e.g., MRS), or functional (revealing signal changes related to neuronal activity, e.g., EEG, MEG, fMRI).

Functional neuroimaging techniques, particularly fMRI, have begun to revolutionize our understanding of the brain’s role in the perception and modulation of pain and provide a glimpse into the brain’s response to a nociceptive stimulus, thereby enabling correlation of brain activity with the person’s perceptions (Borsook and Becerra, 2006). A large number of brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hypothalamus, hippocampus, primary and secondary somatosensory cortex, and others, have been identified as being involved with pain processing and modulation.

Functional neuroimaging also has yielded information about the brain regions involved in the cognitive and emotional factors that modulate pain, including attention (Petrovic et al., 2000), anticipation (Koyama et al., 2005), fear/ anxiety (Ochsner et al., 2006), empathy (Ochsner et al., 2008), reward (Younger et al., 2010a), placebo (Wagner et al., 2004), and direct control (deCharms et al., 2005). Such studies have demonstrated that pain evokes a response in multiple areas of the brain—a “distributed network”—consistent with the variety of physical, affective, cognitive, and reflexive reactions to pain that people experience. Additionally, the involvement of multiple brain areas and their independent, parallel organization for transmission of nociceptive information are “quantitatively related to subjects’ perceptions of pain intensity” (Coghill et al., 1999, p. 1939). These same brain regions also have been observed to undergo plastic changes as a consequence of chronic pain, changes that are visible only now because of these new technologies.

Researchers also have used structural neuroimaging to characterize anatomical changes in the brains of people with chronic pain. Although structural imaging yields no direct information about neural function, it provides indirect information about how chronic pain affects central plasticity and identifies the anatomical differences between people with chronic pain and those who are healthy. For instance, researchers have demonstrated abnormal gray matter changes in the brains of people with chronic low back pain, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorders (Apkarian et al., 2004; Kuchinad et al., 2007; Younger et al., 2010b). Structural imaging can be used to track longitudinal changes due to disease severity and progression and can characterize changes following treatment.

While there is great interest in understanding the function and structure of individual brain regions, researchers increasingly are appreciating that the manner in which these brain regions are connected (i.e., networked) may be more important in understanding pain. For example, a growing body of research is focused on examining resting state functional connectivity changes in the human brain. The theory is that the brain defaults to an intrinsic pattern of brain networks when at wakeful rest. Several abnormal resting state brain networks have been identified

in various chronic pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain (Cauda et al., 2009a,b, 2010; Napadow et al., 2010).

To overcome the limitations posed by using a single neuroimaging technique, researchers now are combining multiple techniques. Recent advances allow researchers to gather both EEG and fMRI data simultaneously, combining the high temporal resolution of the former with the high spatial resolution of the latter. Future research on chronic pain will witness the integration of structural, functional, chemical, and resting state network methods to build a more complete picture of the brain. Combined use of these methods has shown promise in the evaluation of other brain-related illnesses, and each adds a unique angle to the investigation of brain structure and function.

Basic research employing neuroimaging has shown which areas of the brain respond to specific nociceptive stimuli in people with acute pain sensitivity and with neuropathic pain. Such findings open up the possibility for new, more targeted treatments. Already, researchers have used biofeedback approaches to train people with chronic pain to control the activation of pain-related brain areas while watching fMRI pictures of their brains in action, resulting in decreased pain perception (deCharms et al., 2005). Again, while still early in development, such a treatment approach suggests opportunities to tailor pain management, in this case under the person’s direct control, to the specific activity patterns of his or her own brain.

Emotional Context

Genetic influences on nociception and the mechanisms associated with the brain’s response are far from the complete story of how individuals actually experience pain and the ways it affects their functioning. Numerous studies have shown the impact that emotions—in part the product of temperament and in part the result of background and acculturation—can have on the experience of pain, both acute and chronic (see, for example, Turk and Monarch, 2002; Vlaeyen and Crombez, 2007; Fernandez and Kerns, 2008). Negative emotions can increase the perception of chronic pain, while pain has a reciprocal effect on mood states. A good example of this interrelationship is that unrelenting pain is an important cause of and contributor to depression and anxiety; as the pain cycle progresses, depression and anxiety increase pain and pain-related disability and reduce quality of life (Bair et al., 2008; Gureje, 2008). To illustrate, greater anxiety and other psychological conditions can increase the self-reported severity of postsurgical pain (Kehlet et al., 2006), as well as increase the amount of analgesia required, the likelihood of serious complications, and the length of hospitalization.

At the same time, positive emotions are associated with better outcomes in people with chronic pain with respect to improvements in their ability to cope with pain and in their social functioning (Park and Sonty, 2010). Positive emotions also are associated with better responses to treatment, reduced disability and

impairment of physical functioning, and improved health-related quality of life and coping (Fisher et al., 2004; Karoly and Ruehlman, 2006).

The negative emotional correlates of chronic pain frequently become more apparent the longer pain persists, even for individuals who wish to be “positive.” For example, emotional distress may be compounded as pain interferes with work, with important social and recreational activities, and with family and social relations. People with chronic pain may come to believe that, despite their being frequent users of the health care system, the system offers them neither cure nor adequate relief. They may believe that others, including family and clinicians, will disbelieve the extent of their pain or dismiss it as “all in your head,” or believe they are a malingerer or a complainer, especially if a sufficient, objective physiological component of their condition cannot be identified. They may withdraw from social interactions and work, become isolated, and thereby experience even greater functional disability (Boersma and Linton, 2006). In this way, a downward spiral of unrelieved pain and loss of social functioning is established.

It is hardly surprising that people experience significant emotional distress when they have persistent pain and related symptoms that impair their ability to function and impede their overall quality of life, often for years. People with many chronic diseases experience comparable emotional consequences. This is not to suggest that the emotional distress caused the pain in the first place. Nevertheless, there may be some individuals whose lifetime history of emotional problems predisposes them to develop persistent pain following an illness or trauma, such as an automobile accident or surgery.

Many people suffer from both persistent pain and a broader mental health disorder. An estimated 40 to 50 percent of people with chronic pain have mood disorders, but the direction of causality is not completely clear and can, in some instances, go either way. Most studies suggest that depressive disorders, for example, tend to occur after chronic pain begins (Fishbain et al., 1997); however, many people so affected have a prior history of depression. In one study of people with chronic disabling occupational spinal cord disorders, some 65 percent were found to have at least one current psychiatric disorder, and 56 percent had a major depressive disorder (Dersh et al., 2006).

One factor that has been suggested as breaking the link between depression and chronic pain is the belief that one can exert some control over the pain. (The latter findings are consistent with research findings on stress in general: that it is not stressful events, per se, that produce ill effects, but the individual’s judgments or appraisals of those events, particularly a perceived lack of control [McEwen, 1998].) The neurotransmitter serotonin is associated with both pain and depression, and some researchers have theorized that a common genetic trait or susceptibility is linked to pain and both depression and anxiety.

Some people with chronic pain fear that movement and exercise will increase their pain or lead to a dire consequence, even paralysis. In fact, at least for people with chronic low back pain, the opposite is generally true, and for that reason,

physical therapy is often part of a comprehensive treatment plan. Helping people overcome their fear of reinjury is an important intervention because, regardless of biomedical findings, this fear is the best predictor of disability for people with low back pain, about two-thirds of whom avoid activities they are capable of doing because they believe they might injure their back (Crombez et al., 1999). For people with low back pain, concern about the physical demands of their job has a greater impact than actual reported pain levels on work-related disability and lost work days.

Anger is a common correlate of chronic pain, and not an illogical one considering the debilitating effects of the disease, confusion in diagnosis and prognosis, frustrations of trial and error in finding the best treatment or combination of treatments, frequent misunderstanding and skepticism by others (including health care providers), impacts on close personal relations, and the like. People understandably desire an immediate “cure” or significant relief, but often no treatments can accomplish this; instead, they are offered a lengthy rehabilitation effort and advice on managing their disability. These circumstances can trigger powerful emotional responses that interfere with rehabilitation and adjustment. In one study, 62 percent of people with chronic pain expressed anger toward health care providers, 39 percent toward significant others, 30 percent toward insurance companies, and so on, but the most frequent target of their anger—among some 74 percent—was themselves (Okifuji et al., 1999).

Ultimately, explicit assessment of the emotional context of pain is necessary to inform a comprehensive, individualized treatment plan. Given the particularly high co-occurrence of psychiatric disorders among people with chronic pain in particular, specific effort to establish and treat any diagnosed clinically significant mood and anxiety disorders (or other psychiatric conditions) is important, even though many of these mood disorders are secondary to the experience of chronic pain. Likewise, it may be important to provide a greater measure of pain assessment and treatment to patients in psychiatric hospitals, substance abuse treatment centers, and other mental health settings as a routine practice. That is, an interdisciplinary approach to diagnosis and management is important, even if coordinated by a single health care provider. Put another way, “Failure to follow a biopsychosocial approach to treatment will likely contribute to prolonged disability in a substantial number of these chronic pain patients” (Dersh et al., 2006, p. 459).

Cognitive Context

People both ascribe meaning to and seek meaning in pain, acute or chronic. Physical and psychological responses to a painful stimulus occur in a context of meaning that affects how pain is perceived—for example, as a dangerous warning sign, a punishment, or a trial to overcome.

People acquire beliefs about pain over a lifetime of experiences and cultural exposures. Whether they regard their pain as a signal of impending damage or

disability, a short-term or permanent condition, controllable or uncontrollable, or whether they believe they must reduce their activity level in response—all these beliefs influence their reactions. In the case of chronic pain, beliefs also affect how well people adjust to pain and whether they actively attempt to cope with it (Balderson et al., 2004). In fact, beliefs, anticipation, and expectation are better predictors of pain and disability than any physical pathology (Turk and Theodore, 2011).

The public’s fear of cancer, for example, is exacerbated by the concomitant fear of having to face unmanageable pain, which affects decision making about medical treatments (Aronowitz, 2010). Thus, many people with cancer interpret brief pain episodes against the frightful backdrop of a serious disease. Negative interpretations may contribute, as one example, to the finding that cancer patients who believed their post–physical therapy pain was due to their cancer reported greater pain intensity than those who attributed this pain to some other cause (Smith et al., 1998).

Research has identified a particular style of thinking—“pain catastrophizing”—as a common maladaptive cognitive response to the experience of pain, particularly chronic pain. When people “catastrophize” their pain—that is, when they tend to ruminate about their pain, magnify pain sensations, and feel helpless about their ability to manage it (in other words, when they believe pain will lead to far worse outcomes than it will)—they not only increase their pain and dysfunction but also slow their recovery and adjustment. Therefore, these catastrophic beliefs must be assessed and addressed (Sullivan et al., 2001; Keefe et al., 2009). Pain catastrophizing interacts closely with the pain-avoidance fears described earlier:

When pain is perceived following injury, an individual’s idiosyncratic beliefs will determine the extent to which pain is catastrophically interpreted. A catastrophic interpretation of pain gives rise to physiological (arousal), behavioral (avoidance), and cognitive fear responses. The cognitive shift that takes place during fear enhances threat perception (e.g., by narrowing of attention) and further feeds the catastrophic appraisal of pain. (Gatchel et al., 2007, p. 603)

Research has shown that correcting harmful and pain catastrophizing beliefs through a treatment plan that includes cognitive-behavioral therapy improves outcomes (Smeets et al., 2006; Buse and Andrasik, 2010). A variety of cognitive-behavioral strategies have been used to build people’s skills in coping with pain, combining education in how beliefs, feelings, and behavior affect pain with training and practice in skills such as relaxation, goal setting, and thinking in new ways (Keefe et al., 2009). Some approaches to reducing pain catastrophizing provide information plus exposure to feared activities to demonstrate that the person’s fears of further injury do not inevitably materialize when physical activities are undertaken.

Because believing one has control over chronic pain decreases the incidence of depression, some clinicians attempt to increase that sense of control and coping

(Keefe et al., 2009). Some people who have been told their pain is chronic have difficulty accepting this diagnosis, and their lives become dominated by attempts to become pain free. The search for total pain relief, while understandable, can lead to doctor shopping; fragmented care; and repeated trials of surgeries, medications, or unproven remedies (Roper Starch Worldwide, 1999). The failure of these repeated (and common) pain treatment efforts undoubtedly undermines the sense of control clinicians may be trying to encourage.

Emphasis increasingly is being placed on encouraging acceptance of some pain and self-management efforts that can improve function and quality of life even if all pain cannot be eliminated. An approach that emphasizes participation in daily activities despite pain and fosters a willingness to have pain present without responding to it may aid in reducing the “distressing and disabling influences of pain” (McCracken et al., 2005, p. 1335).

Self-efficacy is a psychological construct related to that of control. Believing that one can perform a task or respond effectively to a situation predicts pain tolerance and improvements in physical and psychological functioning. Research therefore suggests that “a primary aim of CLBP [chronic low back pain] rehabilitation should be to bring about changes in catastrophic thinking and self-efficacy” (Woby et al., 2005, p. 100). Likewise, greater self-efficacy improves pain, functional status, and psychological adjustment (Keefe et al., 2004). Researchers posit several explanations for why self-efficacy works to control pain, including that people who expect success are less likely to be stymied when confronting the challenge of pain.

The goals of self-management and self-efficacy reinforce the benefits that accrue when people take a role in managing their pain, and treatment should include efforts to help them perform that role effectively. However, clinicians must take into account that people have unique capacities and cannot be held to a single, universal expectation for self-management. From acute to chronic pain, the salience of individual, subjective responses is paramount.

THE NEED FOR A CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION

For at least two decades, most major medical journals and the lay media have recognized that many patients have needless pain.

——Von Roenn et al., 1993

Barriers to improved pain care exist at multiple levels: at the system level, where changes are needed in reimbursement policy and research emphasis, for example; at the clinician level, where improvements are needed in clinical educa-

tion and practice; and at the level of the public and the individual person in pain, where greater awareness is needed of the significance of pain, as is more education about self-management and appropriate treatment. At all levels, the focus should be on prevention. Overcoming the barriers to improved pain care will, in the committee’s view, require a cultural transformation. This transformation will lead to a greater awareness of the impact of pain on individuals and society, wider support of efforts to understand and prevent pain, a greater commitment to assessing and treating pain effectively, and enhanced recognition of the highly individual ways in which people experience pain and respond to treatment.

Overview of Barriers to Improved Pain Care

This section provides a brief overview of the barriers to improved pain care. A more detailed discussion is contained in Chapter 3.

System-Level Barriers

Although there may be much more to learn about pain and its management, scientific knowledge has advanced to the point where much is understood about the biological–cognitive–emotional aspects of pain and quite a bit about ways to treat it. Throughout the health system in general, however, exist barriers to achieving the ideal of comprehensive and interdisciplinary approaches to health care, including pain management (IOM, 2009). Many of these barriers are institutional, educational, organizational, and reimbursement-related. These same structural barriers channel the health system’s attention to procedure-oriented treatments rather than prevention, but preventing pain (for example, acute pain following surgery or dental procedures) and preventing the transition from acute to chronic pain should be top clinical priorities.

In the United States, clinical services (and research endeavors) generally are organized along disease-specific lines. Thus there are departments of neurology and neurosurgery, cardiology centers, free-standing surgeries, orthopedic and cancer hospitals, and so on. Acute and chronic pain are features of each of these specialties; in a sense, however, because pain belongs to everyone, it belongs to no one. The existing clinical (and research) silos prevent cross-fertilization of ideas and best practices. Although academically based pain clinics implement the comprehensive, interdisciplinary approaches to pain assessment and treatment that appear to work best in managing chronic pain, they are few in number and increasingly constrained by a reimbursement system that discourages interdisciplinary practice.

Clinician-Level Barriers

Clinicians can, in theory, draw on many disciplines in addressing the pain-related needs of individuals and families: physicians of several specialties, nurses,

psychologists, rehabilitation specialists (physiatrists, physical therapists, and occupational therapists), clinical pharmacists, and complementary and alternative medicine practitioners (chiropractors, massage therapists, and acupuncturists, for example). Yet while a substantial amount of acute and chronic pain can be relieved with proper treatment by a single clinician or the appropriate mix of trained professionals, providers encounter a number of barriers to appropriate pain care:

- Well-validated evidence-based guidelines on assessment and treatment have yet to be developed for some pain conditions, or existing guidelines are not followed.

- Health care professionals are not well educated in emerging clinical understanding and best practices in pain prevention and treatment.

- Should primary care practitioners want to engage other types of clinicians, including physical therapists, psychologists, or complementary and alternative medicine practitioners, it may not be easy for them to identify which specific practitioners are skilled at treating chronic pain or how they will do so.

- A lack of understanding of the importance of pain management exists throughout the system, starting with patients themselves and extending to health care providers, employers, regulators, and third-party payers.

- Regulatory and law enforcement policies constrain the appropriate use of opioid drugs.

- Restrictions of insurance coverage and payment policies, including those of workers’ compensation plans, constrain the ability to offer potentially effective treatment.

- Additional basic and clinical research is needed on the underlying mechanisms of pain, reliable and valid assessment methods, the development of new treatments, and the comparative effectiveness of existing treatments.

Patient-Level Barriers

Adequate pain treatment and follow-up may be thwarted by a mix of uncertain diagnosis and the societal stigma that is applied, consciously or unconsciously, to people reporting pain, particularly if they do not respond readily to treatment. Questions and reservations may cloud perceptions of clinicians, family, employers, and others: Is he really in pain? Is she drug seeking? Is he just malingering? Is she just trying to get disability payments? Certainly, there is some number of patients who attempt to “game the system” to obtain drugs or disability payments, but data and studies to back up these suspicions are few. The committee members are not naïve about this possibility, but believe it is far smaller than the likelihood that someone with pain will receive inadequate care. Religious or moral judgments may come into play: Mankind is destined to suffer;

giving in to pain is a sign of weakness. Popular culture, too, is full of dismissive memes regarding pain: Suck it up; No pain, no gain.

When people perceive a lack of validation or other negative attitudes in their clinicians, they are more likely to be dissatisfied with treatment and change doctors, as is the case with about half of people with noncancer pain. In a survey of more than 2,600 Americans with chronic, severe, noncancer pain conducted in 1998 (Roper Starch Worldwide, 1999), 47 percent reported that they had changed doctors, and the largest subgroup of these respondents (22 percent) had done so three times or more. Among the top reasons cited for changing doctors were “doctor didn’t take pain seriously enough” (29 percent) and “doctor didn’t listen” (22 percent), although the most common reason was “still had too much pain” (42 percent). Changing doctors may help if the next clinician is more skilled or empathetic or has better ideas for treatment, or it may hurt if all the change accomplishes is to interrupt the continuity of care.

Additional patient-level barriers are specific to particular demographic groups disproportionately undertreated for pain, such as children, older adults, women, rural residents, individuals with less education or lower incomes, and people belonging to certain racial and ethnic groups. These issues are discussed in Chapter 2.

The Necessary Cultural Transformation

Proponents of international efforts to improve pain treatment have said that “the unreasonable failure to treat pain is viewed worldwide as poor medicine, unethical practice, and an abrogation of a fundamental human right” (Brennan et al., 2007, p. 205). The IASP and its European Federation have urged the World Health Organization (WHO) to recognize that “pain relief is integral to the right to the highest attainable level of physical and mental health” (WHO, 2004), paralleling language found in the WHO Constitution.

With the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in March 2010, the U.S. health care system may undergo profound changes, although how these changes will evolve over the next decade is highly uncertain. Health care reform or other broad legislative actions may offer new opportunities to prevent and treat pain more effectively. Both clinical leaders and patient advocates must pursue these opportunities and be alert to any evidence that barriers to adequate pain prevention and treatment are increasing.

To remediate the mismatch between knowledge of pain care and its application will require a cultural transformation in the way clinicians and the public view pain and its treatment. Currently, the attitude is often denial and avoidance. Instead, clinicians, family members, employers, and friends inevitably must rely on a person’s ability to express his or her subjective experience of pain and learn to trust that expression, and the medical system must give these expressions credence and endeavor to respond to them honestly and effectively.

Conclusion. Chronic pain alone affects the lives of approximately 100 million Americans, making its control of enormous value to individuals and society. To reduce the impact of pain and the resultant suffering will require a transformation in how pain is perceived and judged both by people with pain and by the health care providers who help care for them. The overarching goal of this transformation should be gaining a better understanding of pain of all types and improving efforts to prevent, assess, and treat pain.

• Understanding the experience and impact of pain:

—Pain is a major problem for individuals, families, and society, with an increasing prevalence, cost, and impact on quality of life and health status.

—The experience of both acute and chronic pain is unique and varies widely among individuals. Pain is influenced by genetics, early life experiences, mood and psychological state, coexisting medical conditions, and environments.

—National surveys and numerous research studies have shown that pain is more prevalent and less likely to be adequately treated in certain population groups, including the elderly, women, children, and racial and ethnic minorities.

—While pain sometimes can serve as a warning sign that protects individuals from further harm, chronic pain is harmful and impairs productivity and quality of life.

—When acute pain persists and becomes chronic, it may in some cases become a disease in its own right, resulting in dysfunction in the central nervous system and requiring a comprehensive treatment approach.

• Improving the assessment and treatment of pain:

—Ongoing pain has been underreported, underdiagnosed, and undertreated in nearly all health care settings.

—Individuals with pain that reduces quality of life should be encouraged to seek help.

—Because there are multiple contributors to and broad effects of chronic pain, comprehensive assessment and treatment are likely to produce the best results.

Finding 1-1. To achieve vital improvements in the assessment and treatment of pain will require a cultural transformation. The committee finds that, to adequately address the impact and experience of pain in the United States, government agencies, private foundations, health care providers, educators, professional associations, pain advocacy groups and organizations that raise public awareness, and payers must take the lead in achieving a cultural transformation with respect

to pain. This transformation should improve efforts to prevent, assess, treat, and better understand pain of all types. The recommendations presented in this report are intended to help achieve this transformation.

Chapters 2 through 5 describe the public health challenge of pain, the practice and educational barriers to prevention and treatment, and issues for further research. In each chapter, the committee offers its findings and recommendations.

The public health challenge is discussed in Chapter 2, which establishes the rationale for considering pain as a public health problem. This chapter describes the magnitude of pain’s impact on Americans, including the population as a whole and, where data are available, high-risk subgroups.

Chapter 3 provides an overview of treatments; describes the major treatment modalities; addresses several issues in pain care practice, including aspects of opioid use; elaborates on selected barriers to effective pain care; and presents pain care models.

Chapter 4 examines the need for improvements in education about chronic pain and its treatment for patients and families, the public, and clinicians.

Chapter 5 defines the challenges in pain research, from basic biomedical and pharmacologic research to the development of new research tools. The current organizational structure and funding for pain research are reviewed, and opportunities for public–private partnerships are described.

Finally, Chapter 6 organizes the recommendations presented in Chapters 2 through 5 into a blueprint for action to address the tremendous burden of pain in America.

American Medical Association Specialty Section Council. 2010. The First National Pain Medicine Summit: Final Summary Report. Pain Medicine 11(10):1447-1468.

Apfelbaum, J. L., C. Chen, S. S. Mehta, and T. J. Gan. 2003. Postoperative pain experience: Results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesthesia & Analgesia 97(2):534-540.

Apkarian, A. V., Y. Sosa, S. Sonty, R. M. Levy, R. N. Harden, and T. B. Parrish. 2004. Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. Journal of Neuroscience 24(46):10410-10415.

Aronowitz, R. 2010. The art of medicine: Decision making and fear in the midst of life. Lancet 375(9724):1430-1431.

Bair, M. J., J. Wu, T. M. Damush, J. M. Sutherland, and K. Kroenke. 2008. Association of depression and anxiety alone and in combination with chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care patients. Psychosomataic Medicine 70(8):890-897.

Balderson, B. H. K., E. H. B. Lin, and M. Von Korff. 2004. The management of pain-related fear in primary care. In Understanding and treating fear of pain, edited by G. J. Asmundson, J. W. S. Vlaeyen, and G. Crombez. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Pp. 267-292.