Building a Sustainable, High-Quality Healthcare System

More than a decade has passed since the Institute of Medicine (IOM) issued its influential reports, To Err Is Human: Building A Safer Health System and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. These reports marked an important milestone in the IOM’s continued efforts to improve our nation’s health and healthcare system. In order to deliver the best possible health care to all Americans, and to do so in an efficient and cost-effective manner, the United States needs to reshape and strengthen its healthcare system. The current system undoubtedly has improved the lives of many individuals and made the nation healthier by a number of measures. But it also is falling short in critical ways. Many people, especially among minority and rural populations, do not have easy access to health care. Gaps among various types of healthcare practitioners put seamless care out of reach. The information that patients and healthcare providers rely on can be biased and untrustworthy, and many of the system’s incentives are misaligned.

The IOM continues to confront these deficiencies and to press government, healthcare institutions and practitioners, and other stakeholders to improve the healthcare system.

Making health care fairer and better

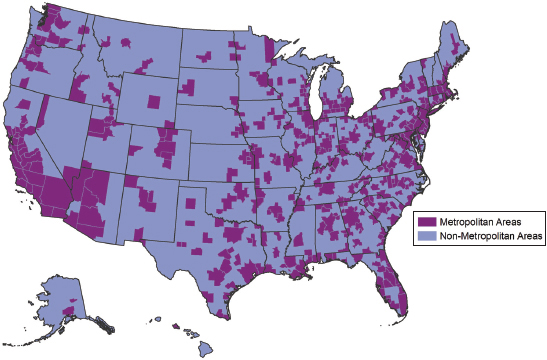

As the nation’s largest health insurer, Medicare has a huge impact on the healthcare system. The program covers 39 million people aged 65 years and older and 8 million people with disabilities. Although it is a national pro-

gram, Medicare adjusts its fee-for-service payments to hospitals, physicians, and other clinical practitioners based on their geographic location. The adjustments are intended to account for the differences in the costs of doing business, such as for staff compensation and payments for hospital or office space, in different regions as well as between urban and rural areas within a region. However, there are disagreements in the provider community and among policy makers about how best to make the adjustments.

Taken together, the recommendations would improve the accuracy of geographic adjustments in payment, streamline the payment process for a broader range of providers, and decrease the burden of cost reporting.

The U.S. House of Representatives called for a study by the IOM in Section 1157 of the Affordable Health Care for America Act, and although it did not end up in the final law, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) sought advice from the IOM on how to improve the accuracy of the data sources and methods used for making the geographic adjustments. The IOM’s resulting report, Geographic Adjustment in Medicare Payment (2011), provides a technical assessment of the data sources and methods used to make adjustments to the hospital wage index and the geographic practice cost indexes.

Based on this assessment, the report recommends that Medicare adopt a more comprehensive approach that would unify the geographic boundaries used for both types of indexes, rely on one source of wage and benefits data for both, and expand the range of occupations covered in the indexes. Taken together, the recommendations would improve the accuracy of geographic adjustments in payment, streamline the payment process for a broader range of providers, and decrease the burden of cost reporting. Implementing the changes will require a phased-in process that invites public comment and combines legislative, rule-making, and administrative actions. A second edition of the report, released in September 2011, makes four additional recommendations on methods to set the work adjustment, calculate labor expenses in the practice expense, and use cost share weights.

SOURCE: RTI Analysis of FY 2011 Wage Index Files, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

In April 2012, the IOM committee responsible for the first geographic adjustment report will issue a second report that evaluates the effects of the adjustment factors on the distribution of the healthcare workforce, on the quality of care provided to patients, on population health, and on the ability of Medicare to provide efficient, high-value care.

Similarly arising from debates during the passage of the Affordable Care Act was a companion study on the value and costs of health care. This IOM study is aimed at understanding which factors contribute to variation and how lessons from existing variation may increase the value of health care in all geographic areas. Already under way, the results of this study are expected in Spring 2013.

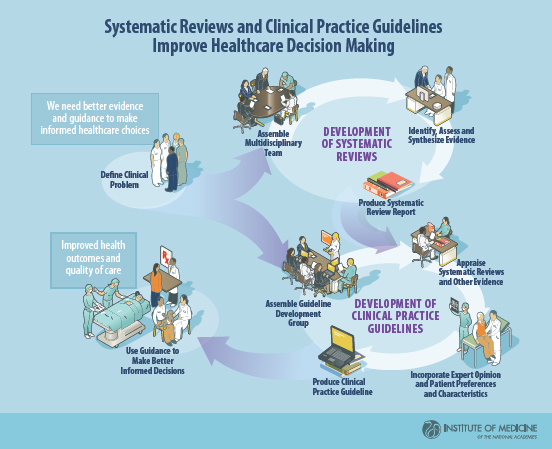

Also at the request of Congress, the IOM examined another key aspect of how the healthcare system performs: the use of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of health interventions and the clinical practice guidelines derived from such reviews.

Patients rely on the expertise and judgment of their doctors to help select the best treatment. Patients can reasonably expect their doctors

and other caregivers to have access to reliable, up-to-date information on health interventions. In making treatment decisions, health professionals commonly consult clinical practice guidelines, which offer an evaluation of the quality of scientific evidence underlying a particular treatment and an assessment of its likely benefits and harms. This information helps a doctor and patient choose the best course based on the individual’s needs and preferences. Clinical guidelines typically are derived from systematic reviews that identify, select, assess, and synthesize the findings of pertinent studies that can help clarify what is known and not known about the potential benefits and harms of drugs, devices, and other healthcare services.

Clinical guidelines typically are derived from systematic reviews that identify, select, assess, and synthesize the findings of pertinent studies that can help clarify what is known and not known about the potential benefits and harms of drugs, devices, and other healthcare services.

Congress sought assistance in the Medicare Improvement for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 by calling for the IOM to recommend standards for conducting systematic reviews and for developing clinical practice guidelines. The IOM formed two committees to respond to each part of this charge.

One of the ensuing reports, Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews (2011), presents a set of 21 methodological standards and 82 elements of performance to be used in systematic reviews. Developing better systematic reviews has the potential to improve decisions made by clinicians, help patients make informed choices about their own care, and provide a more trustworthy basis for decisions by payers and policy makers. Improved systematic reviews also will aid professional medical societies and other organizations that develop clinical practice guidelines.

The proposed standards span the entire process, from formulating the topic and building a review team, to collecting and evaluating evidence, and finally to developing and using the systematic review and communicating results to others. Although they represent current best practices, the proposed standards are not meant to be the last word. Rather, they should be considered provisional, pending better empirical evidence about their scientific validity, feasibility, efficiency, and ultimate usefulness in healthcare decision making.

The report also concludes that the environment surrounding the development of systematic reviews lacks adequate funding and coordina-

tion. Many organizations conduct systematic reviews, but typically they do not work together. Greater collaboration is needed among government agencies, medical professional societies, researchers, and patient interest groups. Together, these groups have the potential to improve the rigor and transparency of systematic reviews, encourage standardization of methods and processes, set priorities for selection of clinical topics of interest to clinicians and patients, reduce unintentional duplication of efforts, and more effectively manage conflicts of interest.

The other committee’s report, Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust (2011), presents a set of eight standards for rigorous, reliable clinical practice guidelines. Of the several thousand guidelines now on the books, most suffer from shortcomings in development, including failure to include a variety of disciplines in the development process, lack of transparency in how recommendations are derived and evaluated, and omission of a thor-

ough external review process. As a result, healthcare practitioners often find it challenging to determine the quality and trustworthiness of most guidelines.

The proposed standards reflect the latest scientific evidence, expert consensus, and public input, and they apply across the entire process of guideline development. Using the standards, institutions and researchers who are involved in guideline development will be better able to generate clinical practice guidelines that will earn the trust of healthcare practitioners and ultimately improve healthcare decision making and health outcomes for patients. To be trustworthy, guidelines should be based on a systematic review of the evidence, developed by a multidisciplinary panel of experts and representatives from key affected groups, consider important patient subgroups and patient preferences, and provide a clear explanation of care options and their expected health outcomes, among other factors. Additionally, development groups should optimally comprise members without any conflicts of interest, or at a minimum, members with a conflict should not represent more than a majority of a group.

To promote adoption of the standards, HHS should create a guide that identifies trustworthy guidelines and that will help healthcare practitioners and patients alike in choosing among treatment alternatives. In addition, the institutions and groups that implement clinical practice guidelines should develop and employ multifaceted strategies targeting both health systems and individuals in order to promote adherence to trustworthy guidelines. Wider adoption of electronic health records and computer-aided clinical decision support systems will open new opportunities to rapidly promote the use of clinical practice guidelines.

Reducing health disparities

The nation’s healthcare system also faces challenges in delivering high-quality care in an equitable manner. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) produces the National Healthcare Quality Report (NHQR) and the National Healthcare Disparities Report (NHDR) annually

at the request of Congress. The reports have revealed that even as healthcare performance has improved, health disparities persist across socioeconomic groups, racial and ethnic populations, and geographic areas. After 5 years of producing the NHQR and NHDR, AHRQ asked the IOM for guidance on how to improve the next generation of reports.

Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports (2010) identifies a number of ways the NHQR and NHDR can be modified to be even more influential in promoting change in the healthcare system. In addition to being sources of data on past trends, the reports can provide more detailed insight into current performance, establish the value of closing gaps in quality and equity, and project the time required to bridge those gaps at the current pace of improvement. The IOM report recommends that AHRQ do the following:

The reports can provide more detailed insight into current performance, establish the value of closing gaps in quality and equity, and project the time required to bridge those gaps at the current pace of improvement.

• Align the NHQR and NHDR with nationally recognized priority areas.

• Select measures that reflect healthcare attributes or processes that have the greatest positive effect on population health.

• Affirm that achieving equity is an essential part of quality improvement.

• Increase the reach and usefulness of AHRQ’s family of report-related products.

• Analyze and present data in ways that will inform policy and promote best-in-class achievement for all actors.

• Identify data needs to set a research and data collection agenda.

The IOM offers a set of national priority areas to enhance quality and eliminate disparities, and it provides a more quantitative and transparent method to evaluate measures for inclusion in the reports. The report also recommends that AHRQ make the extensive compendia of data in the NHQR and NHDR more user friendly in order to engage readers and spur action. The reports should convey what different audiences or stakeholders can do, what levels of performance have been achieved, and where readers can find information on effective interventions that might facilitate prog-

The Committee’s Eight Recommended National Priority Areas for Healthcare Quality Improvement

The IOM Committee on Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports recommends a set of eight national priority areas for healthcare quality improvement for use in the NHQR and NHDR; it believes these priorities can guide the national healthcare reports. The recommended areas include six priority areas identified by the National Priorities Partnership (NPP, 2008), as well as two additional priorities that the committee believes are important to highlight.

The six NPP priority areas included in the committee’s set of national priority areas are:

1. Patient and family engagement: Engage patients and their families in managing their health and making decisions about their care.

2. Population health: Improve the health of the population.

3. Safety: Improve the safety and reliability of the U.S. healthcare system.

4. Care coordination: Ensure patients receive well-coordinated care within and across all healthcare organizations, settings, and levels of care.

5. Palliative care: Guarantee appropriate and compassionate care for patients with life-limiting illnesses.

6. Overuse: Eliminate overuse while ensuring the delivery of appropriate care.

The two additional priority areas in the committee’s set are:

7. Access: Ensure that care is accessible and affordable for all segments of the U.S. population.

8. Health systems infrastructure capabilities: Improve the foundation of healthcare systems (including infrastructure for data and quality improvement; communication across settings for coordination of care; and workforce capacity and distribution among other elements) to support high-quality care.

SOURCE: Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports, p. 3.

ress. Incorporating benchmarks that illustrate the best known levels of performance that have been obtained will enable various entities—states, for example—to compare their current performance against the best in class.

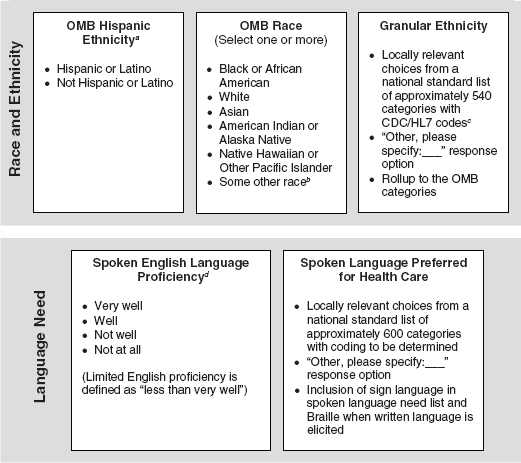

Another IOM study committee examined the health disparities found in AHRQ’s reports from a different perspective. To reduce disparities, it is important to identify which populations are most at risk. One key way of doing this is to collect data on race, ethnicity, and English-language proficiency among various populations, as these factors have been demonstrated to affect the quantity and type of health care that they receive.

To reduce disparities, it is important to identify which populations are most at risk.

At AHRQ’s request, the IOM committee examined ways to collect and use such specialized data. Race, Ethnicity, and Language Data: Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement (2009) offers a number of recommendations. The report recommends that AHRQ align its data classifications with the categories used by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and also develop more fine-grained categories of ethnicity (referred to as granular ethnicity) based on one’s ancestry and language need. The OMB uses only five categories, sorted by race: Black or African American, White, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. But these are not always sufficiently descriptive to target interventions most effectively to various ethnic populations, especially to those of Hispanic ethnicity. Further, there is no way to distinguish whether a Hispanic child, for example, has a Mexican or Cuban background, even though such distinctions can be associated with differences in use of healthcare services and health outcomes.

Collecting more detailed, granular ethnicity data can help in tailoring healthcare delivery to local populations. Hospitals, health plans, and physician practices can use the data to understand the population being served, ameliorate disparities in care, and monitor improvements. States and health plans also can use the data for cross-institutional comparisons to detect variations in quality of care between entities serving similar populations. Legislation supports the collection of these data to improve quality and reduce disparities, and the data need to continue to be handled properly to maintain the public’s trust.

HHS can help promote an expanded role for data collection by developing and distributing lists of categories for granular ethnicities and language needs, and by incorporating the collection of such data in all federally funded healthcare-related programs and electronic health record stan-

Recommended variables for standardized collection of race, ethnicity, and language need.

NOTE: Additional categories for health information technology tracking might include whether respondents have not yet responded (unavailable), refuse to answer (declined), or do not know (unknown), as well as whether responses are self-reported or observer-reported.

a The preferred order of questioning is Hispanic ethnicity first, followed by race, as OMB recommends, and then granular ethnicity.

b The U.S. Census Bureau received OMB permission to add “Some other race” to the standard OMB categories in Census 2000 and subsequent Census collections.

c Additional codes will be needed for categories added to the CDC/HL7 list.

d Need is determined on the basis of two questions, with asking about proficiency first. Limited English proficiency is defined for healthcare purposes as speaking English less than very well.

SOURCES: CDC, 2000; Office of Management and Budget, 1997b; Shin and Bruno, 2003; U.S. Census Bureau, 2002.

SOURCE: Race, Ethnicity, and Language Data: Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement, p. 3.

dards. States, professional organizations, and other public and private entities involved in the provision of healthcare services should follow this lead.

Reinvigorating cancer clinical trials

Advances in biomedical research yield new opportunities to improve cancer prevention, detection, and treatment. Translating such discoveries into meaningful advances in cancer care depends on an effective clinical trials system. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) supports the nation’s largest network for clinical trials of any type. The network’s main component is the Clinical Trials Cooperative Group Program, whose 10 separate research groups work collaboratively with thousands of institutions and investigators to enroll more than 25,000 patients in clinical trials each year.

Despite its long record of accomplishment, however, the Cooperative Group Program is at a critical juncture. Numerous challenges—financial, bureaucratic, and scientific—threaten its ability to conduct the timely, large-scale, innovative clinical trials needed to improve patient care. In this light, the NCI asked the IOM to assess the state of cancer clinical trials, review the Cooperative Group Program, and provide advice on improvements.

The resulting committee’s report, A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program (2010), calls for preserving and strengthening the unique capabilities of the program while improving components that are not working well. The program needs to reorganize its structures and operations to become a truly national clinical trials network. The NCI should lead in instituting the necessary changes, but other federal agencies, such as the Food and Drug Administration, as well as academic centers, community practices, and the pharmaceutical industry, will need to be involved as well.

To guide this transformation, the report identified four main areas for improvement, noting that improvements will be needed in all of the areas; modifying any single element of the Cooperative Group Program will not suffice:

• Improve the efficiency of clinical trials, and reduce the average time for the design and launch of trials.

Summary of the Committee’s Goals and Recommendations

Goal I. Improve the speed and efficiency of the design, launch, and conduct of clinical trials

1. Review and consolidate some front office operations of the Cooperative Groups on the basis of peer review

2. Consolidate back office operations of the Cooperative Groups and improve processes

3. Streamline and harmonize government oversight

4. Improve collaboration among stakeholders

Goal II. Incorporate innovative science and trial design into cancer clinical trials

5. Support and use biorepositories

6. Develop and evaluate novel trial designs

7. Develop standards for new technologies

Goal III. Improve prioritization, selection, support, and completion of cancer clinical trials

8. Reevaluate the role of NCI in the clinical trials system

9. Increase the accrual volume, diversity, and speed of clinical trials

10. Increase funding for the Cooperative Group Program

Goal IV. Incentivize the participation of patients and physicians in clinical trials

11. Support clinical investigators

12. Cover the cost of patient care in clinical trials

SOURCE: A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program, p. 11.

• Make optimal use of innovations in science and trial design.

• Adequately support the clinical trials that have the greatest possibility of improving survival and quality of life for cancer patients, and increase the rate of clinical trial completion and publication.

• Incentivize the participation of patients and physicians in clinical trials by providing adequate funds to cover the costs of research and by reimbursing the costs of standard patient care during the trial.

In March 2011, the IOM’s National Cancer Policy Forum and the American Society of Clinical Oncology held a workshop to pursue ways to achieve the goals and implement the recommendations from the 2010 IOM report. Speakers discussed how to work toward increasing the efficiency and productivity of the clinical trials system.

Reducing costs while enhancing the value of health care

In addition to examining ways to improve particular healthcare initiatives, the IOM, through its Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care, has explored ways to save money and improve health outcomes across the healthcare landscape. Healthcare cost increases continue to outpace the price and spending growth rates for the rest of the economy by a considerable margin. At $2.5 trillion and 17 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product in 2009, health spending commanded twice the per capita expenditures of the average for other developed nations. Moreover, there are compelling signals that much of the additional health spending does little to improve health.

Healthcare cost increases continue to outpace the price and spending growth rates for the rest of the economy by a considerable margin.

With the support of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, the IOM roundtable hosted a series of meetings of experts under the umbrella theme “The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes.” Participants discussed the nature of excess health costs, current evidence on the effectiveness of approaches to their control, opportunities for improving health outcomes, and policy options for achieving these aims. The overarching goal was to explore ways to reduce healthcare costs by 10 percent within 10 years without compromising patient safety, health outcomes, or valued innovation.

The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary (2010) encapsulates the discussions. Workshop participants considered the nature and size of excess costs stemming from problems in six domains: unnecessary services, services inefficiently delivered, prices that are too high, excess administrative costs, missed prevention opportunities, and medical fraud. This comprehensive framework examined and compared all the sources of excess costs in a detailed way, highlighting the factors that drive excess costs. They also considered factors that give rise to unnecessary costs, including scientific uncertainty; perverse economic and practice incentives; system fragmentation; opacity as to cost, quality, and outcomes; changes in the population’s health status; lack of patient engagement in decisions; and underinvestment in population health.

Discussions of strategies and policies to lower costs and improve health outcomes centered on a number of key levers. These included:

• streamlined and harmonized health insurance regulation;

• administrative simplification and consistency;

• payment redesign to focus incentives on results and value;

• quality and consistency in treatment, with a focus on treatments that

• are medically complex;

• evidence that is timely, independent, and understandable;

• transparency requirements as to cost, quality, and outcomes;

• clinical records that are reliable, sharable, and secure;

• data that are protected, but accessible for continuous learning;

• culture and activities framed by patient perspective;

• medical liability reform; and

• prevention at the personal and population levels.

In addition to its concern with cost savings, the Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care also has examined the promise and application of digital technologies in health and health care. Progress in computa-

tional science, information technology, and biomedical and health research methods have made it possible to foresee the emergence of an adaptive “learning health system” that enables both the seamless and efficient delivery of best care practices and the real-time generation and application of new knowledge. With sponsorship from the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information, part of HHS, the roundtable convened a series of meetings of experts to explore strategies for accelerating this transformation. This marked the latest roundtable workshop in the Learning Health System Series, which dates to 2006 and has resulted in nearly a dozen reports intended to outline the conceptual foundation of the learning health system.

In Digital Infrastructure for the Learning Health System: The Foundation for Continuous Improvement in Health and Health Care: Workshop Series Summary (2010), participants from a variety of fields explored a system in which healthcare providers and patients will have access to timely, accurate, and comprehensive health information that can be used to deliver services effectively and efficiently. Information technology will serve as the functional engine for the system. The digital infrastructure would enable data to be collected during activities in various settings—clinical, research, and public health. These data would then be integrated, analyzed, and broadly applied to inform and improve clinical care decisions, promote patient education and self-management, design public health strategies, and support research and knowledge development efforts in a timely manner.

The digital infrastructure would enable data to be collected during activities in various settings—clinical, research, and public health.

Workshop participants examined the vision of such a learning health system, the current state of the system, the key priorities for future work, and the strategic elements for accelerating progress toward a continuous learning health system. Collectively, the discussions captured an unprecedented promise for innovation and progress in health and health care. At the same time, bringing this potential to fruition will require coordinated efforts by many stakeholders to create the conditions necessary for seamless interoperability, to build the protocols for enhanced access and use of available information for knowledge generation, and to nurture a culture of engagement and support around a digital platform to promote continuous learning and improvement.

Advancing integrative medicine

Integrative medicine is emerging as a promising, multidimensional approach to protect and promote good health. Integrative medicine can be described as orienting the healthcare system to engage patients and caregivers in the full range of physical, psychological, social, preventive, and therapeutic modalities and elements known to preserve and restore optimal health. Integrative medicine focuses on efficient, evidence-based practice, prevention, wellness, and patient-centered care, creating a more personalized, predictive, and participatory healthcare experience.

Integrative medicine is emerging as a promising, multidimensional approach to protect and promote good health.

With support from The Bravewell Collaborative, the IOM convened the Summit on Integrative Medicine and the Health of the Public in February 2009. At the meeting, one of the largest and most diverse ever at the IOM, speakers and attendees examined the science and practice of integrative medicine, including successes from clinical settings across the country, and suggested elements of an agenda to help improve the prospects for integrative medicine’s contributions to better health and health care.

Integrative Medicine and the Health of the Public: A Summary of the February 2009 Summit, presents a variety of speakers’ and participants’ suggestions for advancing the field, including redesigning study protocols to better accommodate multifaceted and interacting causal factors; developing pilot projects to identify effective integrated approaches that demonstrate value, sustainability, and scalability; and strengthening and redirecting education and training programs. Throughout the summit, speakers highlighted the need for public policy incentives that would support the necessary developments in research, education, and practice, in particular those that encourage care coordination, team care, patient engagement, and an orientation to prevention and well-being.