Military and Veterans: Protecting the Protectors

The men and women of the U.S. military face many health threats. Combat carries risks of injury or death. Personnel serving away from battle zones may also encounter toxic chemicals or other hazardous materials that are used in or arise from warfare or the environment. Deployment in dangerous areas can generate extreme stress. The health effects of these and other threats may be immediate or develop later, even long after a service member has returned home. Some effects can last a lifetime.

The Department of Defense (DoD) bears the primary responsibility for protecting service members on active duty and providing them with high-quality health care. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides health care to service members after they leave the military. To help in carrying out their missions, the DoD and the VA regularly request that the Institute of Medicine (IOM) study and recommend actions on a range of health-related topics.

Health effects of serving in Iraq and Afghanistan

Protecting the health and well-being of the military personnel who are serving or have served in Afghanistan and Iraq stands as an immediate challenge to the federal government. Roughly 2.1 million men and women, including those drawn from military reserve units and the National Guard, have served in Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom and in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom, often experiencing multiple deployments.

At the end of their deployments, most of the troops successfully readjust to life away from war. But others have difficulty in returning or transitioning to family life, to their jobs, and to living in their communities after deployment. Numerous media reports have suggested that for many service members, the challenge of readjustment is made worse by various health problems, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and traumatic brain injury (TBI).

For many service members, the challenge of readjustment is made worse by various health problems, including post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury.

In response to these concerns, Congress, in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2008, directed the DoD, in consultation with the VA, to sponsor an IOM study of the physical and mental health and other readjustment needs of current and former service members deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan and their families. The IOM appointed a committee of experts to conduct the study, which would be done in two phases.

In its report on the first phase, Returning Home from Iraq and Afghanistan: Preliminary Assessment of Readjustment Needs of Veterans, Service Members, and Their Families (2010), the committee identified the most pressing needs of this population, based in large part on a review of the scientific literature and on testimony from veterans and their families at several town-hall meetings across the country. The report commended the DoD and the VA for their efforts to help returning troops and their families but concluded that critical gaps remain.

One key need is to improve scientific understanding of long-term management of TBI, which has been called the signature wound of the fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. The VA established a comprehensive system of rehabilitation services for TBI, focused on needs that arise in the initial months and years after injury. But protocols to manage the lifetime effects of TBI have not been studied in either military or civilian populations. The committee recommends that the VA sponsor research to determine the efficacy and cost effectiveness of potential protocols for managing TBI—as well as other types of injuries resulting from multiple traumas—over the long term.

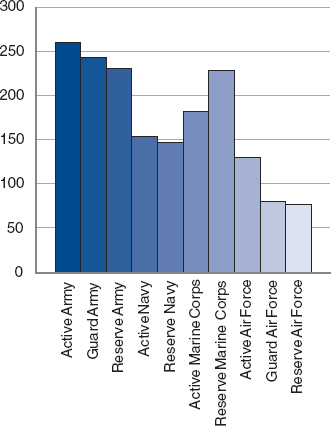

Average time spent deployed in days by branch of military subdivided by active component and reserve component and reserve component.

SOURCE: Returning Home from Iraq and Afghanistan: Preliminary Assessment of Readjustment Needs of Veterans, Service Members, and Their Families, p. 27.

The DoD and the VA also need to ensure there are enough mental health professionals in the healthcare systems serving current and former military personnel and their families to provide treatment to those who suffer from PTSD, substance abuse, and other mental health problems, and that these providers are located where they are needed. On an overarching level, the VA needs to institute a process for forecasting the amount and types of resources necessary to meet health requirements of the veterans and their families well into the future. Requests for disability care and compensation by veterans of previous wars did not peak until 30 years or more after their service ended, and this pattern may hold for Iraq and Afghanistan military personnel and their families as well. The VA currently lacks a mandate and resources to make such long-range projections, limiting the

agency’s ability to plan for the infrastructure, workforce, and other needs when demand is likely to be greatest.

In the report, the committee also presents a framework for the second phase of its study. The aim is to provide a systematic review of interventions to ease readjustment to civilian life, to identify gaps in research, and to identify challenges in accessing care. The second report is expected in spring 2013.

Concurrently, the IOM is looking at the long-term health effects of exposure to burn pits, used to dispose of waste in Iraq and Afghanistan. Using the Balad Burn Pit in Iraq as an example, an IOM committee is examining the feasibility and design issues of an epidemiologic study of veterans exposed to the burn pit and their health outcomes as well as exploring background information on the use of burn pits in the military. A final report is expected in fall 2011.

The IOM also is studying ongoing efforts in the treatment of PTSD. The two-part study, mandated by Congress, will collect and analyze data on DoD and VA programs and methods available for the prevention of PTSD and the screening, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation of members of the Armed Forces and veterans diagnosed with PTSD. The first of two reports is expected in summer 2012.

Treating Traumatic Brain Injury

As Returning Home from Iraq and Afghanistan and other reports have made clear, TBI is common among soldiers who have fought in Iraq and Afghanistan. By one estimate, 10 to 20 percent of veterans returning from those conflicts have sustained a traumatic brain injury. The IOM has substantial experience in this area, having published—sometimes with other units of the National Academies—at least eight reports dealing with TBI in both military and civilian contexts over the past decade.

10 to 20 percent of veterans returning from those conflicts have sustained a traumatic brain injury.

In recent studies of methods for treating TBI, there is evidence that nutritional interventions in the minutes or hours following injury may be effective in improving health outcomes and may even offer some degree of resilience to TBI. In light of such findings, the DoD asked the IOM to convene an expert committee to review the potential role of nutritional interventions.

In Nutrition and Traumatic Brain Injury: Improving Acute and Subacute Health Outcomes in Military Personnel (2011), the committee describes what is known—and unknown—about a number of potential interventions. Given the complexity of TBI and the current gaps in scientific knowledge, the committee could identify only one method that can immediately improve treatment efforts: early feeding of patients with severe TBI. This approach involves giving patients specified levels of energy and protein within the first 24 hours and continuing the course for at least 2 weeks. Early feeding is likely to limit the person’s inflammatory response, which typically is at its peak during the first 2 weeks after an injury, and thereby improve the ultimate health outcome. The committee recommends that the DoD take the lead in developing feeding protocols that require standardized early nutrition delivery for patients with severe TBI, and that hospital intensive care units that treat military personnel should include these protocols in their critical care guidelines.

Early feeding is likely to limit the person’s inflammatory response, which typically is at its peak during the first 2 weeks after an injury, and thereby improve the ultimate health outcome.

Although not as far advanced, a number of other nutritional interventions show therapeutic promise as well. The interventions target specific physiological processes involved in TBI, and they act by restoring cellular energy processes, reducing inflammation and oxidative stress, or repairing brain functions by regenerating neurons or revascularizing damaged tissue. Researchers within the DoD and elsewhere should expand studies of these interventions to demonstrate their effectiveness and safety.

Outside of the laboratory, the DoD should improve assessment of the nutritional status of military personnel, especially those deployed in combat areas, to determine whether there are nutrients that need to be added to their diets to help provide at least some resistance to TBI.

Beyond nutritional interventions, the IOM continues to study TBI and consider treatment options. A study currently under way is tasked with designing a methodology to review, synthesize, and assess the available evidence and experience from the field to determine the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation therapy (CRT) for the treatment of TBI. The DoD asked the IOM to convene a committee to determine the effects of specific CRT treatment on improving attention, language and communication, memory, visuospatial perception, and such executive functions as problem solving and awareness. The IOM’s final report is expected in fall 2011 and

will include recommendations pertaining to the safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of CRT.

Health effects of the Gulf War

The federal government also conducts programs to monitor and protect the health of military personnel who served in the Persian Gulf War. Following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, the United States led an international coalition of armed forces in Operation Desert Shield, which began in January 1991 and ended roughly 3 months later with a ceasefire agreement. Almost 700,000 U.S. troops, including many members of the Reserves and National Guard, took part in the conflict.

On returning home, a substantial number of the troops reported health problems that they believed to be connected to their service. At the request of Congress, the IOM has conducted a series of studies that have examined the scientific and medical evidence on the health effects of the various agents to which military personnel may have been exposed. Beginning in 2000, the IOM has reported on numerous health outcomes related to possible exposures in the Gulf; that work has resulted in the studies in the Gulf War and Health series, which currently includes eight volumes.

As part of this effort, the Department of Veterans Affairs in 2005 asked the IOM to appoint an expert committee to review what was known about the current status of veterans’ health. In its report, Gulf War and Health, Volume 4: Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War (2006), the committee found that many veterans reported that they were troubled by a combination of medically unexplained symptoms, often including chronic fatigue, muscle and joint pain, sleep disturbance, difficulty with concentration, and depression. Veterans also reported numerous other health problems, including chronic pain, gastrointestinal disorders, skin disorders, and respiratory disorders.

Research on the conditions continued, and in 2009 the VA asked the IOM to update its earlier work, based on the latest scientific literature. In

Summary of Findings Regarding Associations Between Deployment to the Gulf War and Specific Health Outcomes

Sufficient Evidence of a Causal Relationship

• PTSD.

Sufficient Evidence of an Association

• Other psychiatric disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and substance abuse, particularly alcohol abuse. These psychiatric disorders persist for at least 10 years after deployment.

• Gastrointestinal symptoms consistent with functional gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia.

• Multisymptom illness.

• Chronic fatigue syndrome.

Limited/Suggestive Evidence of an Association

• ALS.

• Fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain.

• Self-reported sexual difficulties.

• Mortality from external causes, primarily motor-vehicle accidents, in the early years after deployment.

Inadequate/Insufficient Evidence to Determine Whether an Association Exists

• Any cancer.

• Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs.

• Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases.

• Neurocognitive and neurobehavioral performance.

• Multiple sclerosis.

• Other neurologic outcomes, such as Parkinson’s disease, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease.

• Incidence of cardiovascular diseases.

• Respiratory diseases.

• Structural gastrointestinal diseases.

• Skin diseases.

• Musculoskeletal system diseases.

• Specific conditions of the genitourinary system.

• Specific birth defects.

• Adverse pregnancy outcomes such as miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm birth, and low birth weight.

• Fertility problems.

Limited/Suggestive Evidence of No Association

• Peripheral neuropathy.

• Mortality from cardiovascular disease in the first 10 years after the war.

• Decreased lung function in the first 10 years after the war.

• Hospitalization for genitourinary diseases.

SOURCE: Gulf War and Health, Volume 8: Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War, p. 8.

Gulf War and Health, Volume 8: Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War (2010), the committee notes there is considerable evidence that deployment is associated with the type of chronic, multisymptom illness reported by many veterans, as well as with various other conditions and diseases, including gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome; substance abuse, particularly alcoholism; chronic fatigue syndrome; and some psychiatric disorders, including anxiety disorder and depression. In addition, there is suggestive, though limited, evidence for an association with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain, sexual difficulties, and death from external causes, including automobile accidents, in the early years after deployment.

For the many other diseases with a suggested possible link to deployment—including various cancers, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia—the committee judged the evidence to be insufficient for making a determination. For a very few health outcomes, including death from cardiovascular disease within 10 years of the war, the committee found some evidence that deployment has no impact, though data are far from complete.

Concluding that there is a pressing need to answer lingering questions, the report offers a detailed action plan. On one front, the government should continue its surveillance of deployed and nondeployed Gulf War veterans. This effort should include assembling methodologically robust cohort groups and carefully tracking their development of a number of diseases, including ALS, multiple sclerosis, brain cancer, and psychiatric conditions, as well as health problems that occur at a later age, such as other cancers, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Renewed effort is needed to better understand the multisymptom illness that affects an estimated 250,000 Gulf War veterans.

On another front, renewed effort is needed to better understand the multisymptom illness that affects an estimated 250,000 Gulf War veterans. Researchers should undertake studies comparing genetic variations and other differences in veterans with and without symptoms. It is likely that the illness results from interactions between genes and environmental exposure, with genetics predisposing some individuals to illness. A consortium involving the VA, the DoD, and the National Institutes of Health could coordinate this effort and contribute the necessary resources. Similarly, expanded clinical trials are needed to develop more

effective methods to treat or even cure multisystem illness—and, ideally, to find ways to prevent such disorders from affecting troops in future deployments.

The VA took quick action. Citing the IOM report, in July 2010 the agency announced a national research program to identify and adopt more effective treatments for multisymptom illnesses in Gulf War veterans. The $2.8 million program, which incorporates recommendations of the VA’s Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses Task Force, will feature three new research projects. Included will be a 5-year study to evaluate the impact of resistance exercise training in treating chronic musculoskeletal pain and related symptoms, a 4-year study using an animal model of multisymptom illness to assess therapies designed to enhance mood and memory, and a 2-year pilot study to compare the effectiveness of certain stress-reduction therapies with conventional care in treating Gulf War veterans. In addition to funding new research, the VA has asked the IOM to evaluate treatments being used to manage chronic multisymptom illness and to recommend those that seem to offer the most benefit and improved health outcomes in those veterans experiencing chronic symptoms.

Tracking the health effects of Agent Orange

From 1962 to 1971, the U.S. military sprayed herbicides, including a mixture called Agent Orange, over parts of southern Vietnam and surrounding areas in order to achieve a number of military goals. Most large-scale sprayings were conducted from airplanes and helicopters, but herbicides were also dispersed from boats and ground vehicles and by soldiers wearing back-mounted equipment. Following the war, many veterans and their families began attributing various chronic and life-threatening diseases to exposure to Agent Orange or to its toxic contaminant, dioxin.

In 1991, Congress directed the IOM to study the veterans’ claims. Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Herbicides Used in Vietnam (1994) provided the first comprehensive, unbiased review of the epidemiological evidence regarding links between such exposure and the full spectrum of adverse health effects, including various cancers, reproductive and developmental problems, and neurobiological disorders. Since then, the IOM has published a series of biennial updates. Collectively, these reports—integrating all the peer-reviewed published literature—provide the scientific basis on which the VA awards disability compen-

sation to Vietnam veterans. The reports also recommend research that could provide more definitive conclusions about possible health effects.

Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2008 was released in 2009. Among key findings, the report concluded that there is suggestive but limited evidence that exposure to Agent Orange and other herbicides is associated with an increased chance of developing ischemic heart disease and Parkinson’s disease in Vietnam veterans. Ischemic heart disease is characterized by reduced blood supply to the heart that can lead to heart attack and stroke. Parkinson’s disease is a degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that can cause movement-related problems and, in later stages, behavioral and cognitive problems.

There is suggestive but limited evidence that exposure to Agent Orange and other herbicides is associated with an increased chance of developing ischemic heart disease and Parkinson’s disease in Vietnam veterans.

In response to a request for clarification by the VA, the committee that conducted the study also affirmed that hairy cell leukemia should be classified with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and lymphomas for compensation purposes. Previous reviews in the series had found sufficient evidence to state that there is an association between herbicide exposure and increased risk for CLL and lymphomas.

But many health questions remain, and the study committee identified a number of areas where continued research is needed. For example, development of animal models of various chronic health conditions and their progression would be useful for understanding whether and how Agent Orange and other herbicides contribute to problems in aging Vietnam veterans. Work also needs to be undertaken promptly to resolve questions regarding several health outcomes, most urgently tonsil cancer, melanoma, and paternally transmitted transgenerational effects.

As a result of the IOM report, Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric Shinseki announced plans in October 2009 to add Parkinson’s disease, ischemic heart disease, and hairy cell leukemia to the list of conditions presumed to be associated with exposure to Agent Orange. These plans became final August 31, 2010. The change makes it substantially easier for thousands of veterans to claim that those ailments were the direct result of their service in Vietnam, thereby smoothing the way for them to receive monthly disability checks from the VA. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2010, the latest report in the series, will be released in fall 2011.

In another study, the IOM examined whether Navy personnel who served aboard deep-water vessels operating off Vietnam might face increased health risks from exposure to Agent Orange or other herbicides. Several recent studies have raised the possibility that these sailors might have been exposed to Agent Orange and its dioxin contaminant, perhaps via onboard distillation systems that converted seawater into potable water. If so, the sailors might face the same health risks as ground troops or sailors in the Brown Water navy who served on vessels that operated in Vietnam waters and along the coastline. Such concerns prompted the VA to commission an IOM study.

During its deliberations, the IOM study committee considered many data sources, including published peer-reviewed literature, models for assessing environmental concentrations of Agent Orange and dioxin, memoirs and other anecdotal information from veterans about their experiences during and after the war, government documents, and ships’ deck logs. The committee also held several open meetings to gather testimony directly from Navy veterans about their experiences with Agent Orange while they served in the Vietnam War.

In its report, Blue Water Navy Veterans and Agent Orange Exposure (2011), the committee concludes that the available evidence is not sufficient to reasonably determine exposure of these sailors to Agent Orange or dioxin. Thus, it is currently impossible to judge whether Blue Water Navy Vietnam veterans might be at higher, lower, or similar risk of long-term adverse health effects associated with Agent Orange exposure than shore-based veterans or Brown Water Navy veterans.

Safeguarding mental health

Combat troops in today’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as their counterparts in other wars, face exposure to a range of traumatic events that can cause immediate or delayed mental health conditions. The DoD provides an array of mental health services, along with other types of health care, through TRICARE, a single-payer program that combines the resources of military treatment facilities with networks of civilian healthcare professionals and medical facilities. A variety of men-

tal health professionals, with differing education, training, and expertise, provide care through the program.

Combat troops in today’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan face exposure to a range of traumatic events that can cause immediate or delayed mental health conditions.

This cadre includes mental health counselors, professionals who typically hold master’s degrees and who are obligated by state licensure and other requirements to have demonstrated clinical experience in order to practice. Under current TRICARE rules, counselors are required to practice under a physician’s supervision, and their patients must be referred to them by a physician in order for their services to be eligible for reimbursement.

In the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2008, Congress requested that the IOM convene a committee to examine the credentials, preparation, and training of licensed mental health counselors. In Provision of Mental Health Counseling Services Under TRICARE (2010), the committee reports that it found no compelling evidence that distinguishes mental health counselors from other classes of practitioners in their ability to serve in an independent capacity or to provide high-quality care. Accordingly, the committee recommends that TRICARE change its policy to permit mental health counselors to practice independently in circumstances where their education, licensure, and clinical experience have helped to prepare them to diagnose and, where appropriate, treat conditions in the beneficiary population. It offered a set of guidelines for determining when these circumstances were fulfilled. The committee recommends that counselors who do not meet the proposed requirements still be allowed to practice within the system to maintain the continuity of care, and that TRICARE consider supervising them in a manner that provides for successively greater levels of independent practice as experience and demonstrated competence increase.

The committee also recommends a more fundamental step, that TRICARE implement a comprehensive quality management system for all of its mental health professionals. This recommendation is built on other IOM reports that suggest that the best way for healthcare providers to deliver high-quality care is by setting appropriate standards of education and training for providers and then promoting evidence-based care standards and the monitoring of results.

After the report’s release, the IOM, at the request of the DoD, held a 3-day workshop in October 2010 to explore the possible structure and implementation of the recommended quality management system. The workshop brought together participants from a variety of groups and with a range of interests, and the discussions are expected to inform efforts to improve the way that TRICARE serves the mental health needs of its beneficiaries.