If bioterrorists released Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) over a large city, hundreds of thousands of people could need rapid access to antibiotics to prevent the deadly inhalational form of anthrax. Delivering antibiotics effectively following an anthrax attack is a tremendous public health challenge, however, because of the large number of people who may be exposed and the brief time window during which people exposed to anthrax spores must start taking antibiotics to prevent illness and death.

This report considers the use of prepositioning strategies to complement current plans for distributing and dispensing anthrax antibiotics, which rely heavily on postattack delivery from the centralized Strategic National Stockpile or state stockpiles. Once delivered to a state or locality, antibiotics from these stockpiles are dispensed to the public primarily via points of dispensing (PODs) located throughout the community. Prepositioning involves the storage of medical countermeasures (such as antibiotics) close to or in the possession of the people who would need rapid access to them should an attack occur. Examples of prepositioning strategies include local stockpiles, workplace caches, and home storage.

![]()

1This summary does not include references. Citations and detailed supporting evidence for the findings presented in the summary appear in the subsequent report chapters.

Although potentially effective for ensuring that large numbers of people have rapid access to antibiotics, prepositioning strategies require more resources than strategies relying on distribution from central locations after an attack, and some could increase health risks. Prepositioning strategies, therefore, provide the greatest value in enhancing response to large-scale attacks in high-risk areas with limited dispensing through the current POD system and in filling specific gaps in current capabilities. Conversely, prepositioning strategies may offer little added value in areas in which the risk of an attack is low or dispensing capability is sufficient.

In their planning efforts, state, local, and tribal officials should give priority to improving dispensing capability and developing prepositioning strategies such as local stockpiles and workplace caches. The committee recommends against broad use of home antibiotic storage for the general population because of concerns about inappropriate use, lack of flexibility as a response mechanism, and high cost. In some specific cases, home storage may be appropriate for individuals or groups that lack access to antibiotics through other timely dispensing mechanisms.

Because communities differ in their needs and capabilities, this report sets forth a framework to assist state, local, and tribal policy makers and public health authorities in determining whether prepositioning strategies would be beneficial for their community. The committee’s recommendations also identify federal- and national-level actions that would facilitate the evaluation and development of prepositioning strategies, including the development of national guidance to enhance public-private coordination on prepositioning, distributing, and dispensing antibiotics for use in response to an anthrax attack.

If bioterrorists released aerosolized Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) over a large city, hundreds of thousands of people could need rapid access to antibiotics to prevent the deadly inhalational form of anthrax. Delivering antibiotics effectively following an anthrax attack is a tremendous public health challenge, however, because of the large number of people who may be exposed and the brief time window during which people exposed to anthrax spores must start taking antibiotics to prevent illness and death.

Since the anthrax attack in 2001, the nation has made much progress in developing plans for the rapid delivery of antibiotics. Nonetheless, there are ongoing concerns about the threat of anthrax, the scope of the public

health challenge of responding to such an attack, the ability to implement the plans that have been developed, and gaps in the performance of the distribution and dispensing system revealed during such recent events as the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. For these reasons, all levels of government—in partnership with the private sector and community organizations—continue to explore ways to improve the nation’s ability to distribute and dispense antibiotics rapidly to the public.

The backbone of current distribution plans is the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a national repository of medicine and medical supplies that can be deployed rapidly around the country to supplement state and local stockpiles. Following an attack, SNS supplies are delivered to state and local public health authorities, who assume responsibility for dispensing the medical countermeasures (MCM), such as antibiotics, to their populations. Currently, the primary delivery model is for the public to receive MCM at points of dispensing (PODs) located throughout the community.

This report examines the use of prepositioning strategies as a complement to the current centralized system. Prepositioning entails the storage of MCM close to or in the possession of the people who would need rapid access to them should an attack occur so as to reduce the time required to distribute and dispense initial doses. Examples of prepositioning strategies include local stockpiles, workplace caches, and home storage. Prepositioning strategies may help individuals receive antibiotics more quickly. In addition, by alleviating the burden on the POD system, some prepositioning strategies may indirectly increase timely access to antibiotics for people who will receive them from PODs, and these strategies could enable public health officials to devote additional efforts to reaching those who may have difficulty accessing MCM through the standard POD system. Discussions about prepositioning strategies over the past several years, however, have raised concern about their potential to introduce increased health risks, increased costs, legal and regulatory issues, questions of equity and fairness, and logistical burdens on public health departments.

Prepositioning is just one potential component of a larger endeavor to enhance the nation’s capability to prevent illness and death from an anthrax attack. Other components include national security efforts to prevent an attack or mitigate its effects; efforts to enhance detection and surveillance capability; further development of strategies for anthrax prevention (e.g., anthrax vaccine) and treatment (e.g., anthrax antitoxin); continuing refinement of the current MCM distribution and dispensing system, including development of a model for using the postal system to deliver antibiotics; and efforts to engage the private sector in both the development and the delivery of MCM.

STUDY CHARGE

Given the potential benefits and concerns associated with prepositioning strategies, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), commissioned the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to undertake a study to inform the use of prepositioned antibiotics for protection against anthrax (Box S-1).

In response to this charge, the committee reviewed the scientific evidence on antibiotics for prevention of anthrax and the implications for

BOX S-1

Statement of Task

In response to a request from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), the Institute of Medicine will convene an ad hoc committee of subject matter experts to inform the use of prepositioned medical countermeasures (MCM) for the public. The committee will focus on prepositioning antibiotics for protection against a terrorist attack using Bacillus anthracis or a similar pathogen. More specifically, the ad hoc committee will produce a report that will:

• Consider the role of prepositioned medical countermeasures for the public (e.g., prepositioning at home, local stockpiles, and workplace caches) within an overall MCM dispensing strategy that includes traditional MCM dispensing and distribution strategies such as points of dispensing (PODs), taking into account both logistical and non-logistical factors (e.g., safety and ethics).

• Identify and describe key factors and variables that should be included in a strategy for prepositioning MCM for the public (e.g., population demographics, threat status, proximity to high-value targets, proximity to healthcare facilities).

• Discuss preliminary considerations for the development of an incremental and phased MCM prepositioning strategy.

• Based on available evidence, describe economic advantages and disadvantages of various MCM prepositioning strategies for the public.

The committee will develop scenarios, as needed, to illustrate the interaction of the strategic considerations, key factors, and variables in different situations and environments. The committee will base its recommendations on currently available published literature and other available guidance documents and evidence, expert testimony, as well as its expert judgment.

decision making about prepositioning; described potential prepositioning strategies; and developed a framework to assist state, local, and tribal public health authorities in determining whether prepositioning strategies would be beneficial for their communities. The committee concluded that each jurisdiction should assess the benefits and costs of prepositioning in their particular community; however, based on an analysis of the likely health benefits, health risks, and relative costs of the different prepositioning strategies, the committee also developed findings and recommendations to provide jurisdictions with some practical insights as to the circumstances in which different prepositioning strategies may be beneficial. Finally, the committee identified federal- and national-level actions that would facilitate the evaluation and development of prepositioning strategies.

ANTIBIOTICS FOR POSTEXPOSURE ANTHRAX PROPHYLAXIS

Inhalational anthrax is considered to be the most dangerous form of anthrax infection resulting from bioterrorism because aerosolized spores of B. anthracis can travel significant distances through the air and have a highly successful infection rate for humans, and because this is the deadliest form of the disease (compared with the more treatable cutaneous and gastrointestinal forms of anthrax). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved four antibiotics for prophylaxis (prevention of disease) following exposure to aerosolized spores of B. anthracis: doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and parenteral procaine penicillin G. These antibiotics protect against anthrax provided (1) the antibiotic used is effective against the particular strain of B. anthracis used in the attack, and (2) exposed individuals begin to take the antibiotic prior to the appearance of symptoms of anthrax. These conditions are highly relevant to decision making about prepositioning, as described below.

Antibiotic-Resistant B. Anthracis

Creating a strain of anthrax that is resistant to one or more antibiotics does not require a high level of microbiologic knowledge, and methodology for doing so is described in the open scientific literature. In 2006, the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued a Material Threat Determination specifically for multi-drug-resistant anthrax.

Concerns about antibiotic-resistant anthrax are relevant to any strategy for distributing and dispensing antibiotics, particularly since laboratory testing of susceptibility of a strain to antibiotics is likely to take 2 days or longer. Given the brief window of time during which people exposed to the spores must receive antibiotics to prevent disease (see section on incubation period below), antibiotic distribution and dispensing efforts would have to

be initiated before the susceptibility profile of the attack strain was known. These concerns may be amplified for prepositioning strategies, because it would likely be prohibitively expensive to stockpile a variety of antibiotics in all locations relative to stockpiling a variety of antibiotics in centralized locations.

Finding 2-12: Prepositioning of a single type of antibiotic (or class of antibiotics) would reduce flexibility to respond to the release of an antibiotic-resistant strain of anthrax, a biothreat recognized by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Furthermore, although some information about planned responses is already available in the public domain, prepositioning antibiotics in the home would provide a greater degree of certainty about the planned response and, therefore, could conceivably increase the probability of release of a resistant strain of anthrax.

Incubation Period

Data on human exposure to aerosolized B. anthracis are limited, however, and there is a great deal of uncertainty regarding the incubation period (time from exposure to appearance of symptoms). Prophylaxis with a single antibiotic begun while an individual exposed to aerosolized anthrax is still in the incubation period can prevent symptoms from occurring. A clear understanding of the incubation period is critical for decision making about effective antibiotic distribution and dispensing strategies, including prepositioning strategies.

An exposed population will exhibit a range of times from exposure to the appearance of symptoms for the exact same exposure/dose, and the shape of the distribution curve is important for decision making about prophylaxis strategies. If, for example, there is a wide range of incubation times, then even after the development of a small number of clinically recognized anthrax cases, sufficient time may exist to distribute and dispense antibiotics to a large fraction of still-asymptomatic persons, thereby protecting a large fraction of the exposed population. On the other hand, if the distribution of incubation times is relatively narrow, then there could be much less time to distribute and dispense antibiotics to the exposed population after initially identified clinical cases. Beyond the shape of the distribution curve, the shortest incubation time that would be expected in an exposed population (i.e., the time at which the first person(s) would begin exhibiting symptoms) also is important for public health decision

![]()

2The findings and recommendations in this report are numbered according to the chapter of the main text in which they appear. Thus, for example, Finding 2-1 is the first finding in Chapter 2.

making about prepositioning. A longer minimum incubation period would permit more time for the distribution of MCM before symptom onset and thus would have a direct impact on decisions regarding the need for prepositioning.

Finding 2-2: Review of the limited available data on human inhalational anthrax shows that people exposed to aerosolized anthrax have incubation periods of 4 to 8 days or longer. Much of the modeling used to derive shorter estimates is based on data from the Sverdlovsk incident,3 and the assumptions made potentially lead to an underestimate of the minimum incubation period.

With the most probable minimum incubation period being approximately 4 days (or 96 hours), there is no compelling evidence to suggest that jurisdictions must plan to complete dispensing of initial prophylaxis more rapidly than 96 hours following the time of the attack, although incremental improvements appear to be achievable and could provide additional protection against unforeseen delays.

Therefore, the current operational goal of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Cities Readiness Initiative of completing dispensing of initial prophylaxis within 48 hours of the decision to dispense appears to be appropriate, as long as the total time from exposure to prophylaxis does not exceed 96 hours. Achieving this goal depends on robust detection and surveillance systems that can rapidly detect an anthrax attack, rapid decision making, and effective distribution and dispensing systems. If detection or decision making is delayed, faster distribution and dispensing may be needed to minimize symptomatic disease in the exposed population.

PREPOSITIONING STRATEGIES

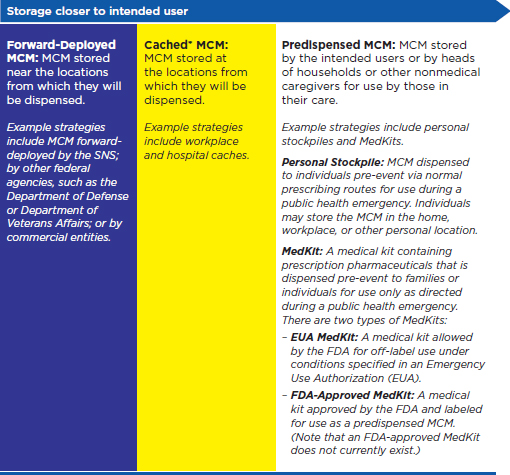

Strategies for storing MCM lie along a continuum based on their proximity to the location of the anticipated event. At one extreme, MCM may be stored in a central warehouse that serves the entire nation (the SNS); at the other extreme, they may be stored in the homes of the intended users. Figure S-1 defines three categories of prepositioning strategies that can be used to complement the existing centralized system: forward-deployed MCM, cached MCM, and predispensed MCM. A mix of strategies along the continuum could be used—for example, some forward-deployed stockpiles near areas of high risk combined with some centrally located stockpiles to serve the remaining areas.

![]()

3The largest anthrax outbreak in history, the Sverdlovsk accident in 1979, is believed to have been the result of an accidental release of aerosolized anthrax from a Soviet Union biological weapons program. The incident is explained in more detail in Chapter 2.

FIGURE S-1

Definitions of prepositioning.

NOTE: FDA = Food and Drug Administration; MCM = medical countermeasures;

SNS = Strategic Natural Stockpile.

* The term cache is often used broadly to describe stockpiles of MCM, whether held by state or local jurisdictions, health care facilities, or private-sector organizations, among others. For the purposes of this report, and to enable clear discussion of the different properties associated with different types of prepositioning, the committee defines cache more specifically as storage in the location from which MCM will be dispensed, and uses the term stockpile to denote federal, state, and local stockpiles.

PUBLIC-PRIVATE COORDINATION

Expanding public-private coordination has the potential to enhance MCM distribution and dispensing capability in communities. Many private-sector entities already play important roles throughout the MCM distribution and dispensing system, including managing inventory and distributing MCM for the SNS. Private-sector entities may be interested in developing or expanding systems through which they can preposition, distribute, and dispense antibiotics to help ensure the safety of employees and their families, provide for business continuity of operations, and potentially reduce insurance costs. Many large private-sector companies already have systems through which they communicate effectively with their employees, and such companies often have medical staff and other resources that could be used to enhance dispensing capability within their community during a time of crisis. As described in this report, however, potential private-sector partners face many barriers in carrying out this role, including liability, cost, legal and regulatory issues, and the complexities of working across multiple jurisdictions during the development of MCM dispensing plans.

Recommendation 4-1: Develop national guidance for public-private coordination in the prepositioning, distribution, and dispensing of medical countermeasures.

The Department of Health and Human Services should convene state, local, and tribal governments and private-sector organizations to develop national guidance that will facilitate and ensure consistency for public-private cooperation in the prepositioning, distribution, and dispensing of medical countermeasures and help leverage existing private-sector systems and networks.

A DECISION-AIDING FRAMEWORK FOR STATE,

LOCAL, AND TRIBAL PUBLIC HEALTH OFFICIALS

Because communities differ in their needs and capabilities, the committee developed a decision-aiding framework to assist state, local, and tribal public health officials in determining whether prepositioning strategies would be beneficial for their community. This framework is summarized in Box S-2. This box is intended to provide an overview of the key elements of the framework; additional details on the recommended actions are provided in the recommendations that follow and in the main text of the report.

BOX S-2

Key Elements of the Decision-Aiding Framework

Communities across the United States differ in their needs and capabilities. Different communities may benefit most from different strategies for prepositioning antibiotics for anthrax, or may not benefit from prepositioning strategies at all. The committee developed a decision-aiding framework to assist state, local, and tribal jurisdictions in deciding which prepositioning strategies, if any, to implement in their community. The key elements of this framework are:

• Assessment of risk and current capabilities — Consideration of the risk of an anthrax attack

— Consideration of the risk of an anthrax attack

— Assessment of current capability for timely detection of an attack

— Assessment of current dispensing capability, including (1) overall dispensing capability, and (2) specific gaps in dispensing capability, such as particular subpopulations not well served by current plans

• Incorporation of ethical principles and community values

• Evaluation of potential prepositioning strategies for medical countermeasures for anthrax — Evaluation of potential health benefits, including evaluation of

— Evaluation of potential health benefits, including evaluation of potential effectiveness in reaching specific populations or filling other specific gaps in dispensing capability

— Evaluation of potential health risks

— Evaluation of likely costs

— Consideration of practicality, including (1) communications needs and expected social behavior and adherence, (2) logistics, and (3) legal and regulatory issues

Assessment of Risk and Current Capabilities

To determine the potential benefits of prepositioning strategies, it is critical for jurisdictions to accurately assess their capabilities for both distribution and dispensing. The few performance measures available with which to assess dispensing capability are still nascent in their development. Existing performance data often are derived from small-scale drills rather than full-scale exercises because of limitations on financial resources and personnel, as well as on the feasibility of interrupting the daily operations of partner entities outside of the public health system. This fact, coupled with limited standardization and comparability of measurements across jurisdic-

tions,makes it difficult to evaluate the current capability of a dispensing system and in turn, the value of adopting prepositioning strategies to augment that capability. While the development of more accurate knowledge of distribution and dispensing capability would likely be more resource-intensive than continuing with current policies, it is a necessary precursor to developing and implementing expensive prepositioning strategies.

Recommendation 5-1: Enhance assessment of performance in implementing distribution and dispensing plans for medical countermeasures.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should continue to facilitate assessment of state, local, and tribal jurisdictions’ performance in implementing dispensing plans for medical countermeasures, in addition to assessing planning efforts. More specifically, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in collaboration with state, local, and tribal jurisdictions, should facilitate assessment of the entire distribution and dispensing system by:

• demonstrating Strategic National Stockpile distribution capabilities to high-risk jurisdictions;

• facilitating large-scale, realistic exercises in high-risk jurisdictions to test dispensing capability; and

• continuing efforts to identify objective criteria and metrics for evaluating the performance of jurisdictions in implementing mass dispensing.

Incorporation of Ethical Principles and Public Engagement

Jurisdictions must ensure that their dispensing plans adhere to ethical principles with respect to both general considerations in drafting public health policy and issues specific to the question of prepositioning anthrax MCM.

Recommendation 5-2: Integrate ethical principles and public engagement into the development of prepositioning strategies within the overall context of public health planning for bioterrorism response.

State, local, and tribal governments should use the following principles as an ethical framework for public health planning of prepositioning strategies:

• Promotion of public health—Strive for the most favorable balance of public health benefits and harms based on the best available research and data.

• Stewardship—Demonstrate stewardship of public health resources.

• Distributive justice—Distribute benefits and harms fairly, without unduly imposing burdens on any one population group.

• Reciprocal obligations—Recognize the professional’s duty to serve and the reciprocal obligation to protect those who serve.

• Transparency and accountability—Maintain public accountability and transparency so that community members grasp relevant policies and know from whom they may request explanation, information, or revision.

• Proportionality—Use burdensome measures, such as those that restrict liberty, only when they offer a commensurate gain in public health and when no less onerous alternatives are both available and feasible.

• Community engagement—Engage the public in the development of ethically sound dispensing plans for medical countermeasures, including plans to preposition antibiotics, so as to ensure the incorporation of community values.

Evaluation of Potential Prepositioning Strategies for MCM for Anthrax

The committee recommends that each jurisdiction assess the benefits and costs of prepositioning in the particular community. Recognizing that some local jurisdictions may have limited resources, the committee recommends that state, local, and tribal jurisdictions work in partnership with each other and with other stakeholders, such as the federal government, the private sector, and community organizations, to gather the necessary information and conduct the recommended assessments and evaluations.

Recommendation 5-3: Consider the risk of attack, assess detection and dispensing capability, and evaluate the use of prepositioning strategies to complement points of dispensing.

State, local, and tribal governments should, in partnership with each other and with the federal government, the private sector, and community organizations:

• Consider their risk of a potential anthrax attack.

• Assess their current detection and surveillance capability.

• Assess the current capability of and gaps in their medical countermeasures dispensing system.

• Based on their risk and capability assessment, evaluate whether specific prepositioning strategies will fill identified gaps and/or improve effectiveness and efficiency. The decision-making framework should include, for a range of anthrax attack scenarios:

— evaluation of the potential health benefits and health risks of alternative prepositioning strategies;

— evaluation of the relative economic costs of alternative prepositioning strategies;

— comparison of the strategies with respect to health benefits, health risks, and costs, taking into account available resources; and

— consideration of ethical principles and incorporation of community values (see Recommendation 5-2).

In the report, the committee presents a qualitative exploration of the potential effects of each of the key elements of the decision-aiding framework on the incremental effectiveness of prepositioning strategies. The committee also presents a first-order quantitative model for estimating health benefits associated with different prepositioning strategies; a discussion and case study of the estimation of likely economic costs; and a suggested method for using estimates of health benefits and economic costs to explore trade-offs associated with alternative prepositioning strategies and inform decision making.

While recommending that each jurisdiction conduct its own analysis, the committee offers findings and recommendations based on its analysis of the likely health benefits, health risks, and relative costs of the different prepositioning strategies to give jurisdictions some practical insights as they consider the strategies’ benefits and costs.

Importance of Adequate Dispensing Capability and Timely Decision to Dispense

In the event of an attack, forward-deploying stockpiles and caches will have the potential to decrease morbidity and mortality only if the community has adequate dispensing capability, and the time from release until dispensing is initiated is brief compared with the minimum incubation period. Analytical models of existing distribution strategies show that in the event of a large-scale attack, dispensing capability—not antibiotic inventories—is likely to be the rate-limiting factor in getting antibiotics to the potentially exposed population.

The benefits of prepositioning, measured in terms of time to prophylaxis and resulting fraction of the exposed population saved, increase as the time from attack until the decision to dispense increases. This result occurs because of the distribution of the incubation period of anthrax across exposed individuals. Reducing time to prophylaxis from 48 hours to 24 hours after exposure, for example, will likely have little impact on the fraction of the exposed population saved because few individuals will develop anthrax symptoms within that period. On the other hand, reducing time to

prophylaxis from, for example, 120 hours to 96 hours after exposure can significantly improve the fraction saved because many individuals are likely to develop anthrax symptoms between 96 and 120 hours after exposure.

Health Benefits, Health Risks, and Costs of Prepositioning Strategies

Prepositioning MCM has the potential to reduce the expected time until exposed individuals in the population receive prophylaxis. If associated with closed PODs, which dispense to a defined population rather than to the general public (e.g., in a private-sector workplace), prepositioned MCM can directly benefit those who receive MCM from the closed PODs, reducing their time to prophylaxis. Moreover, by reducing demand at public PODs, prepositioning can indirectly benefit those who receive MCM from public PODs, reducing their time to prophylaxis as well.

Although potentially effective for ensuring that large numbers of people have rapid access to antibiotics, prepositioning strategies will require more resources than strategies that rely on distribution from central locations after an attack, will decrease flexibility (e.g., to redeploy based on attack location or to provide alternative MCM based on the susceptibility of the strain), and may increase potential health risks. Therefore, prepositioning strategies will provide the greatest value in enhancing response to large-scale attacks in high-risk areas with limited dispensing through the current POD system and in filling gaps in coverage of subpopulations that could be addressed effectively through prepositioning. Conversely, prepositioning strategies may offer little added value in areas in which the risk of an attack is low or dispensing capability is sufficient.

Table S-1 summarizes factors that affect the appropriateness of each strategy and the consequences of its implementation. The table consists of a set of suggested “if-then” rules, stored in its rows: if a situation is well described by the entries in a row under “Factors Affecting the Appropriateness of Strategies,” then the strategy or strategies in that row might be appropriate to consider. The right side of the table describes qualitatively the consequences of implementing such a strategy.

Recommendation 5-4: Give priority to improving dispensing capability and developing prepositioning strategies such as forward-deployed or cached medical countermeasures.

In public health planning efforts, state, local, and tribal jurisdictions should give priority to improving the dispensing capability of points of dispensing and push strategies and to developing forward-deployed or cached prepositioning strategies.

The committee does not recommend the development of public health strategies that involve broad use of predispensed medical

TABLE S-1

Appropriateness and Consequences of Alternative Prepositioning Strategies: Qualitative Summary

| Continuum of MCM Storage Locations | Strategies to Considera | Factors Affecting Appropriateness of Strategies | Consequences of Strategies | |||||

| Risk Statusb | Public Health Dispensing Capabilityc | Gaps in Subpopulations Coveredd | Cost to Public Healthe | Time to Prophylaxisf | Inventory Flexibilityg | Potential for Misuseh | ||

| No Pre-positioning | – Centralized stockpiles (SNS, other) | Low | Adequate | None | Limited | Baseline | Greatest | None |

| Forward-Deployed MCM | – SNS forward-deployed – Other federal forward-deployed (e.g., DOD, VA) – Private forward-deployed |

High | Adequate | n/a | Moderate | Shorter | Medium | None |

| Cached MCM | – Hospital/pharmacy caches – Workplace caches |

High | Limited | Some | Moderate | Shorter | Less | Some/little |

| Predispensed MCM | – Personal stockpiles | Extremely High | Inadequate | Many | Limited | Shortest | Least | Moderate/high |

| – MedKits | High | |||||||

NOTE: DOD = Department of Defense; MCM = medical countermeasures;

n/a = not applicable. SNS = Strategic National Stockpile; VA = Department of Veterans Affairs;

aCombinations of strategies may be appropriate.

bLikelihood of an attack and likelihood of an attack of a given type or size.

cMCM dispensing capability in the event of a large attack.

dSubpopulations that may not be covered by MCM dispensing capacity in the event of an attack.

eThe cost incurred by public health authorities to store and maintain inventories of MCM. Other costs may be borne by other entities, such as private-sector workplaces (e.g., storage, training, and maintenance of workplace caches) and individuals or private insurers (e.g., personal stockpiles). Research and development costs for MedKits may be borne by the federal government, by a private-sector company, or by some combination of these.

fThe time from the decision to dispense until MCM can be delivered to all exposed and potentially exposed individuals.

gInventory flexibility includes the potential for use of multiple drugs, the potential for redeployment of inventories based on need, and the ease with which stockpiles can be rotated.

hPotential for misuse of the prepositioned MCM (e.g., individuals taking the antibiotics for other conditions or not in the event of an anthrax attack).

countermeasures for the general population. In some cases, however, targeted predispensed medical countermeasures might be used to address specific gaps in jurisdictions’ dispensing plans for certain subpopulations that lack access to antibiotics via other timely dispensing mechanisms. These might include, for example, some first responders, health care providers, and other workers who support critical infrastructure, as well as their families.

Personal stockpiling might also be used for certain individuals who lack access to antibiotics via other timely dispensing mechanisms (e.g., because of their medical condition and/or social situation) and who decide—in conjunction with their physicians—that this is an appropriate personal strategy. This is allowed under current prescribing practice and would usually be done independently of a jurisdiction’s public health strategy for dispensing medical countermeasures.

The available evidence and reasoning leading to the committee’s conclusions and recommendations with respect to predispensed MCM are summarized below.

Predispensed Medical Countermeasures

Predispensing of MCM is unique relative to other potential prepositioning strategies because it puts the MCM directly into the hands of the intended end-users. Potential health risks are thereby introduced that are not entailed in prepositioning strategies such as forward-deployed and cached MCM. As noted above, predispensing also increases costs and decreases flexibility to alter the MCM provided based on the specifics of an attack. The committee considered two potential predispensing strategies: predispensing to the general public in a community and predispensing for targeted subpopulations. The committee also considered the likely relative risks, benefits, and costs of different forms of predispensing (e.g., MedKits and personal stockpiling).

The use of predispensing as a broad public health strategy for the general public is unlikely to be cost-effective and carries significant risks. The most extensive body of relevant evidence (statistics about the misuse of antibiotics prescribed for routine medical care) suggests that if predispensing were implemented broadly for the general public, the rate of inappropriate use could be high, resulting in increased health risks to individuals and the community. Concerns include inappropriate use in routine settings (e.g., using the antibiotics to treat a cold) and widespread inappropriate use in response to events such as a distant anthrax attack, a false alarm caused by a nonanthrax white-powder event, or another public health emergency for which antibiotics are not indicated.

Based on a community’s comprehensive assessment of risk and current dispensing capability, predispensing could prove to be an appropriate strategy for specific groups and individuals who would not have access to prophylactic antibiotics via other timely dispensing mechanisms. For these groups and individuals (examples of which are given in Recommendation 5-4 above), the risk of not getting antibiotics following an anthrax attack may outweigh the potential health risks associated with inappropriate use. In addition, with a more limited, targeted strategy, or a strategy that involves a direct relationship between patient and physician, it may be easier to provide patient education about proper antibiotic use, institute systems to decrease inappropriate use and manage costs, and/or develop an alternative dispensing mechanism in case of an attack with antibiotic-resistant anthrax.

With regard to the form of the MCM that might be predispensed to these targeted groups and individuals, the intent of special MedKit packaging (relative to personal stockpiling with standard prescription vials) is to decrease misuse, but the committee found no direct evidence of this benefit. Future studies may be able to demonstrate that special packaging for MedKits could decrease the rate of inappropriate use.

Recommendation 5-5: Do not pursue development of a Food and Drug Administration–approved MedKit unless this is supported by additional safety and cost research.

The committee does not recommend the development of a Food and Drug Administration–approved MedKit designed for prepositioning for an anthrax attack until and unless research demonstrates that MedKits are significantly less likely to be used inappropriately than a standard prescription and can be produced at costs comparable to those of standard prescription antibiotics.

RECOMMENDED ACTIONS FOR MOVING FORWARD

To provide a plan for moving forward, the committee organizes its recommendations into those addressed to state, local, and tribal public health officials and those intended for implementation at the federal/national level. Recognizing that implementation of these actions should involve partnerships among all levels of government and nongovernmental stakeholders, this division is intended to indicate the entity or entities recommended to take the leading role, not the sole actor(s). Box S-3 lists the committee’s recommendations in these two categories. The committee notes that, although these actions are proposed in the context of the selection, development, and implementation of prepositioning strategies, many also would help enhance the nation’s overall ability to distribute and dispense antibiotics

BOX S-3

Recommendations at the State/Local/

Tribal and Federal/National Levels

State/Local/Tribal

Different communities may benefit most from different strategies for prepositioning antibiotics for anthrax, or may not benefit from pre-positioning strategies at all. The following recommendations are intended to assist state, local, and tribal public health officials in evaluating the potential benefits, health risks, and costs of developing prepositioning strategies in their community:

• Integrate ethical principles and public engagement into the development of prepositioning strategies within the overall context of public health planning for bioterrorism response. (Recommendation 5-2)

• Consider the risk of attack, assess detection and dispensing capability, and evaluate the use of prepositioning strategies to complement points of dispensing. (Recommendation 5-3)

• Give priority to improving dispensing capability and developing prepositioning strategies such as forward-deployed or cached medical countermeasures. (Recommendation 5-4)

Federal/National

• Develop national guidance for public-private coordination in the prepositioning, distribution, and dispensing of medical countermeasures. (Recommendation 4-1)

• Enhance assessment of performance in implementing distribution and dispensing plans for medical countermeasures. (Recommendation 5-1)

• Do not pursue development of a Food and Drug Administration– approved MedKit unless this is supported by additional safety and cost research. (Recommendation 5-5)

• Perform additional research to better inform decision making about prepositioning strategies. (Recommendation 6-1)

rapidly following an anthrax attack regardless of specific decisions made about prepositioning.

Finally, throughout the report, the committee highlights areas of uncertainty in the evidence and research that would help inform decision making on prepositioning strategies.

Recommendation 6-1: Perform additional research to better inform decision making about prepositioning strategies.

Results of such research would strengthen the decision-aiding framework proposed in this report for determining whether prepositioning strategies would be beneficial within a community. The Department of Health and Human Services should conduct additional research in the following broad areas: epidemiological and medical issues regarding anthrax and postexposure prophylaxis for anthrax, operations and logistics, behavior and communications, safety, and cost-effectiveness.