Putting a value on the impact of violence, while often an incomplete picture, provides evidence for investing in preventive interventions. Both enumerated and estimated costs—economic and social—indicate an enormous burden on public health. In particular, violence at specific points along the life span can have a greater impact. Also, addressing violence after it occurs, in addition to preventing the recurrence of violence, can be costly.

Thus, investing in early prevention can have significant financial benefit. It can prevent violence before it begins, or it can prevent the development of longer-term outcomes of violence.

The first paper in this section examines the value of prevention, by exploring the costs of violence and the costs of intervention. It also explores different methods of assessing value to highlight the importance of a number of perspectives on prevention.

The second paper is an example of a community-based preventive intervention that builds resiliency and prosocial behavior in individuals and the community as a whole. It also demonstrates the cost-effectiveness of prevention.

Rachel A. Davis, M.S.W.

Prevention Institute

Prevention has tremendous value, and there are many ways to think about its value in the context of preventing violence. Prevention is a systematic process that reduces the frequency or severity of illness or injury,

and primary prevention promotes healthy environments and behaviors to head off problems before the onset of symptoms.

Ten ways of thinking about the value of prevention are the following:

- Direct costs of not preventing violence

- Indirect costs of not preventing violence

- Savings due to prevention

- Advantages of a prevention approach

- Partnerships and multisector collaboration

- A good solution solves multiple problems

- Prevention works

- Multiplier effect

- Efficient government

- Prevention reduces suffering and saves lives

Direct Costs of Not Preventing Violence

One way to appreciate the value of preventing violence is to understand the costs of violence. A single violent incident is far more expensive than many realize. For example:

- Every fatal assault costs $4,906 on average, with another $1.3 million in lost productivity (Corso et al., 2007).

- Every nonfatal assault costs approximately $1,000 on average, with $2,822 in lost productivity (Corso et al., 2007).

- The economic cost of violent deaths was $47.2 billion in 2005. This includes medical treatment and lost future wages (CDC, 2011).

- The cost of sexual and domestic violence exceeded $5.8 billion— $319 million for rape, $4.2 billion for physical assault, and $1.75 billion in lost earnings and productivity (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2003).

On top of the cost to the government and the taxpayer for each individual act of violence, add the expense of long-term incarceration for perpetrators:

- The American Correctional Association estimates that it costs states an average of $240.99 per day—around $88,000 a year—for every young person housed in a juvenile facility in 2008 (Justice Policy Institute, 2009).

- States spent approximately $5.7 billion to imprison 64,558 young people across the United States in 2007 (Puzzanchera and Sickmund, 2008).

These costs are incurred for every incident of violence that is not prevented. More than 650,000 young people ages 10 to 24 are treated every year in emergency departments for injuries sustained from violence, and homicide is the second leading cause of death among youth between the ages of 10 and 24 (CDC, 2010). When that many young people regularly experience violence in their neighborhood or at home, the cost can only increase.

The Advancement Project in Los Angeles attempted to account for these costs in one locale, and its analysis demonstrated that gang violence in the City of Los Angeles cost the city, the County of Los Angeles, and the State of California $1.145 billion every year in criminal justice costs alone (Vera Institute of Justice, 2011). This astronomical amount, $1.145 billion, covers only the criminal justice costs of arresting and processing gang members in a single city. Imagine how high this amount would be if the analysis included other kinds of violence, factored in costs in addition to criminal justice, and covered cities across the United States, not just Los Angeles. Multiply $1.145 billion by those factors, and this will provide an approximate idea of how expensive violence can be.

Violence is enormously costly in services after the fact, including medical care, criminal justice, social services, and law enforcement. Treating gang members’ gunshot wounds in the City of Los Angeles (LA), for example, costs the government approximately $45,296,446 annually in medical care (Vera Institute of Justice, 2011). Altogether, victims of LA gang violence pay more than $1 billion in out-of-pocket and quality-of-life costs (Vera Institute of Justice, 2011).

Interventions at the first sign of trouble are unusual, so it is not atypical for one individual to have many interactions with the criminal justice system over decades. A child whose first memories are of violence is far more likely to perpetuate violence throughout life. Frequently when a child victim of violence is not cared for at the first sign of trouble, that child grows up to be an adult victim of violence and is repeatedly suspected and arrested for violent crime. Every subsequent encounter that one child has with the criminal justice, social services, and medical systems as he grows up makes violence more and more expensive for communities, taxpayers, and the larger society.

These expenses pile up when violence is not prevented, and “economic costs provide, at best, an incomplete measure of the toll of violence,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2007). This suggests that the true cost of violence is actually far greater than that captured by the direct costs.

Indirect Costs of Not Preventing Violence

Another way to think about the value of prevention is to consider the indirect costs when violence is not prevented. Violence reduces tourism and

neighborhood business activity, resulting in the loss of private revenues and public tax dollars. It also undermines health and can exacerbate and contribute to the onset of chronic conditions and mental health problems.

Mental Health

Those who fear violence and those who experience violence as victims, perpetrators, and witnesses also suffer emotional and mental health consequences. These enduring negative effects can span a lifetime, require extensive treatment, and in turn affect physical health. Research has identified the following mental health conditions as significantly more common among those exposed to violence, either directly or indirectly:

- Depression and risk for suicide (Campbell, 2002; Chilton and Booth, 2007; Clark et al., 2008; Curry et al., 2008; Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Latkin and Curry, 2003; Paolucci et al., 2001; Pastore et al., 1996; Veenema, 2001)

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Paolucci et al., 2001; Veenema, 2001)

- Aggressive and/or violent behavior disorders (Campbell, 2002; Fowler et al., 2009; Paolucci et al., 2001; Veenema, 2001)

Youth with past exposure to interpersonal violence have significantly higher risk for PTSD, major depressive episodes, and substance abuse and dependence. In many U.S. neighborhoods, violence is so traumatizing that 77 percent of children exposed to a school shooting and 35 percent of urban youth exposed to community violence develop PTSD, far higher than the rate for soldiers deployed to combat areas in the last 6 years (20 percent) (Kilpatrick et al., 2003; National Center for PTSD, 2007, 2009).

Chronic Diseases

Violence can also affect changes that undermine our overall health. Violence is associated with a broad range of chronic illnesses, such as

- Asthma (Apter et al., 2010; Fujiwara, 2008; Sternthal et al., 2010; Suglia et al., 2009; Wright and Steinbach, 2001; Wright et al., 2004);

- Heart disease and hypertension (Carver et al., 2008; Felitti et al., 1998);

- Ulcers and gastrointestinal disease (Prevention Institute, 2011b);

- Diabetes (Carver et al., 2008; Felitti et al., 1998);

- Neurological and musculoskeletal diseases (Prevention Institute, 2011b); and

- Lung disease (Carver et al., 2008; Felitti et al., 1998).

Violence and fear of violence are also significant barriers to healthy eating and active living. People are less likely to use local parks or walk to school when they do not feel safe in their neighborhood, for example, and violence reduces investments in communities—for example, by grocery stores (Bennett et al., 2007; Shaffer, 2002; Zenk et al., 2005). This means that safety concerns cause people to exercise less and spend less time outdoors (Burdette et al., 2006; Carver et al., 2008; CDC, 1999; Eyler et al., 2003; Gomez et al., 2004; Harrison et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2009; Loukaitou-Sideris, 2006; Lumeng et al., 2006; Molnar et al., 2004; Sallis et al., 2008; Weir et al., 2006; Williamson et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2004; Yancey and Kumanvika, 2007).

Violence also alters people’s purchasing patterns and limits access to healthy food (Bennett et al., 2007; Neckerman et al., 2009; Odoms-Young et al., 2009; Vasquez et al., 2007; Zenk et al., 2005). Experiencing and witnessing violence cause trauma and can decrease motivation and capability to eat healthfully and be active (Alvarez et al., 2007; Boynton-Jarrett et al., 2010; Chilton and Booth, 2007; Felitti et al., 1998; Frayne et al., 2003; Greenfield and Marks, 2009; Vest and Valadez, 2005). Violence and fear of violence diminish community cohesion, which reduces support for healthy eating and active living (Cradock et al., 2009; Harrison et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2009; Odoms-Young et al., 2009; Rohrer et al., 2004; Vest and Valadez, 2005). Chronic illness resulting from unhealthy eating and activity account for a growing percentage of escalating costs in the healthcare system (Hogan et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2009; Prevention Institute, 2010; Prevention Institute et al., 2007; Thorpe et al., 2004).

Savings Due to Prevention

Given the expense of violence is in terms of dollars and community health, there is increased recognition that prevention is a smart investment. Prevention preempts both the direct and the indirect costs of violence and translates into huge savings.

Direct Savings

By preventing violence before it happens, investments are made now rather than paying more later to cover the outsized after-the-fact costs of violence. Investing in programs such as high-quality preschool, for example, can yield immense savings. A cost-benefit analysis of the High Scope

Perry Preschool Program showed a return of $16.14 per dollar invested (Schweinhart et al., 2005). By age 40, the African-American children who participated in the preschool program as 3- and 4-year-olds had significantly fewer arrests for violent crime, drug felonies, and violent misdemeanors and served fewer months in prison compared to nonparticipants (Schweinhart et al., 2005). Every child who grows up safe and healthy means one more person who does not encounter these institutions and systems.

Indirect Savings

Reducing violence is an effective way to stimulate economic development in affected communities (Bollinger and Ihlanfeldt, 2003; Lehrer, 2000), and preventing violence yields indirect savings by promoting health in the long run. Preventing violence would reduce demand for healthcare services by lowering these incidence and prevalence rates, which would void the associated healthcare costs for thousands of people who would otherwise have fallen ill.

Advantages of a Prevention Approach

Criminal justice has historically received most attention when it comes to violence, but effectively addressing this problem requires an approach that emphasizes prevention and also includes intervention, enforcement, and successful reentry. This prevention-oriented approach provides a methodology that extends beyond programs and has the potential to change systems and shape social norms. This additional capacity is another way to weigh the value of prevention.

According to an Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2000) report on behavior change, “It is unreasonable to expect that people will change their behavior easily when so many forces in the social, cultural, and physical environment conspire against such change.” Rather than intervening after people are injured and working with one individual at a time, primary prevention means changing the larger environment before problems arise.

A complex issue such as violence requires a multifaceted, comprehensive solution. Rather than only working with one person at a time to treat the effects of violence or to increase individual knowledge and skills, prevention also addresses the underlying causes of violence at the community and societal levels. Although single programs have been shown to reduce violence, there is a continuous need for comprehensive approaches, for effectiveness and to ensure sustainability.

Partnerships and Multisector Collaboration

No sector alone can prevent violence. Cities need integrated strategic plans and coordinated efforts across multiple sectors such as education;

health and human services, including public health, substance abuse and mental health, and children and families; criminal justice; early childhood development; and labor. For example, the UNITY Assessment found that cities with more multijurisdictional coordination and communication have lower rates of violence (Weiss and Southern California Injury Prevention Research Center, 2008).

Coming together and owning the solutions across multiple sectors are key, and prevention informs and facilitates this process. To effectively address violence, multiple sectors must be at the table to develop and implement a comprehensive solution. Another way to understand the value of prevention is to appreciate how it relies on inclusive processes and creates space for all these partners to dialogue and collaborate, as well as clarifying the roles of multiple sectors, such as addressing the complex array of risk and resilience factors. Approaching violence from only a criminal justice perspective limits the types of partners involved and narrows the scope of possible solutions, whereas focusing on prevention brings multiple partners to the table.

A Good Solution Solves Multiple Problems

Addressing the risk and resilience factors of violence through prevention reduces the likelihood of other poor health and behavior outcomes, such as teen pregnancy, substance abuse, mental health problems, and school failure (Felitti, 2002; Shonkoff et al., 2009). Preventing violence is valuable because it addresses risk factors that overlap with other poor health and behavior outcomes. Efforts to prevent violence simultaneously prevent these other problems as well. Boosting the resilience factors that make violence less likely also protects a community against these other problems.

Reducing violence increases the efficacy of other health initiatives. Policies that support communities to effectively prevent violence will improve health—for example, by improving access to healthy food and safe places to be active (Odoms-Young et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2004) and enabling economic development in underdeveloped areas.

Prevention Works

Prevention is valuable because it is effective. There is a growing evidence base, grounded in research and community practice, confirming that violence is preventable. Universal school-based programs can reduce violence by 15 percent in as little as 6 months (Hahn et al., 2007), for example, and street outreach and interruption strategies reduce shootings and killings by 40 to 70 percent (Skogan et al., 2008).

Early results from the Blueprint for Action in Minneapolis indicate that it is possible to reduce the likelihood of violence. The Minneapolis City Council unanimously passed a resolution that declared youth violence a public health issue and mandated a multifaceted long-term solution to address youth violence called the Blueprint for Action. As a result, homicides of youth decreased by 77 percent between 2006 and 2009 (City of Minneapolis, 2011). The number of youth suspects dropped by 60 percent from 2006 to 2010, and the number of youth arrested for violent crime is down by one-third of what it was 4 years ago (Rybak, 2011). In addition, high school graduation rates at Minneapolis public schools increased to nearly three out of four in 2010, up from only 55 percent in 2005 (City of Minneapolis, 2011). As a result of this remarkable early success, the Blueprint for Action expanded its programs from the 4 initial neighborhoods to 22 neighborhoods in 2009 (Prevention Institute, 2011).

Multiplier Effect

Another way of thinking about the value of prevention is in its myriad long-term benefits. The benefits of preventing violence are multiplied because preventing violence generates a ripple effect and a slew of positive outcomes. Preventing violence can initiate a cascade of improved health and savings. Investing in prevention reduces the prevalence and severity of violence and related injury and disability, as well as of associated conditions, such as chronic disease, mental illness, and poor learning. This means reduced healthcare expenditures related to violence and associated health conditions. People who would otherwise be hospitalized, sick, injured, or disabled due to violence or associated health conditions can continue to work and study, which yields savings in terms of increased attendance and productivity.

Efficient Government

Prevention is valuable because it promotes efficient government when embedded in existing efforts, policies, and practices. It can contribute to efficiencies within local, state, and federal agencies; reduce duplication of efforts; create opportunities to leverage existing resources; and allow for the alignment of resources. Partners can share information and resources and minimize “reinventing the wheel.” Further, embedding efforts to prevent violence within multiple agencies and sectors (e.g., housing, economic development, public works, education) can leverage existing resources for maximum benefit.

Prevention Reduces Suffering and Saves Lives

The value of prevention can also be measured in the ways it fosters well-being and promotes healthy communities. Prevention yields all of these savings and benefits, and it also spares victims, perpetrators, and their loved ones the heartache, grief, and pain that violence causes. In addition to monetary expenses, violence incurs costs that cannot easily be calculated, such as the potential of young lives lost too soon, reduced quality of life, and neighborhoods in which people neither trust each other nor venture outside due to fear.

Summary

These are some ways to appreciate the value of prevention. Violence is extremely costly, not just in terms of lives, but also in the form of criminal justice expenses, medical costs, lost productivity, and disinvestment. Further, violence and trauma are linked to the onset of chronic diseases and mental health problems, and caring for chronic diseases represents the most costly and fastest-growing portion of healthcare costs for individuals, businesses, and government. Yet violence is preventable, and prevention is of great value by any criteria.

For many young people, violence is the most pervasive aspect of growing up in their neighborhood. Young people need connection, identity, opportunity, and hope. When these things are not provided, young people turn elsewhere for them, and too often they turn to gangs and to violence. We do know how to provide these things in communities, and we need to make this a priority. Prevention values lives.

J. David Hawkins, Ph.D., Richard F. Catalano, Ph.D.,

and Margaret R. Kuklinski, Ph.D.

Social Development Research Group,

University of Washington School of Social Work

Prevention science emerged in the late twentieth century as a discipline built on the integration of life course development research, community epidemiology, and preventive intervention trials. Advances in prevention science have important implications for the healthy development of adolescences. Researchers have identified longitudinal predictors, such as family conflict or early academic failure, that increase the likelihood that young

people will engage in problem behaviors associated with significant morbidity and, in some cases, mortality. Other predictors, such as strong bonds to positive adults or the development of specific competencies, are protective, associated with reducing problem behaviors and increasing favorable outcomes such as academic success, even in the presence of risk. As shown in Table 8-1, many of these risk and protective factors are common to multiple adolescent problem behaviors, which suggests that improvements in risk and protection can affect a broad set of outcomes simultaneously. Researchers have used this research base on risk and protection to design and evaluate prevention programs in controlled trials and have found a number of them effective in reducing risk factors, enhancing protective factors, and reducing problem behaviors. Over time, an evidence base of “what works” has been established, and several lists of tested and effective programs have been made available to the public. Implementing scientifically tested and effective prevention programs to address youth risk and protective factors is a viable strategy for reducing prevalent and costly problem behaviors, including adolescent substance use and delinquency.

In spite of these advances, scientifically based approaches have not been widely used in schools and communities, and effective prevention systems have not been broadly established. Reasons include a lack of knowledge about scientifically proven prevention programs, difficulty marshaling resources for science-based prevention and health promotion efforts, and failure to implement proven programs with fidelity. The Communities That Care (CTC) prevention system, which mobilizes community stakeholders to collaborate on the development and implementation of a science-based community prevention system, was developed to address these concerns (Hawkins and Catalano, 1992). CTC has been developed over more than 20 years and has improved through community and research input. Here, we describe the CTC approach to prevention, steps involved in its implementation, major findings from a randomized controlled trial, and its dissemination (Hawkins and Catalano, 1992).

Implementing Communities That Care

A major challenge for prevention scientists committed to applying research in the “real world” is to increase the use of tested and effective prevention policies and programs while recognizing that communities differ from one another and need to decide locally what policies and programs to use. Hawkins and Catalano developed CTC, a coalition-based system for preventing a wide range of adolescent problem behaviors, including substance use and delinquency, with these needs in mind.

CTC is guided by the Social Development Model, which holds that in order to develop healthy, positive behaviors, young people must be

TABLE 8-1 Many Youth Problem Behaviors Share Underlying Risks

| RISK FACTORS | Substance Abuse | Delinquency | Teen Pregnancy | School Drop-Out | Violence | Depression and Anxiety |

| Community | ||||||

|

Availability of drugs |

✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Availability of firearms |

✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Community laws and norms favorable to drug use, firearms, and crime |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Media portrayals of violence |

✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Media portrayals of substance abuse |

✓ | |||||

|

Transitions and mobility |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

|

Low neighborhood attachment and community disorganization |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Extreme economic deprivation |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| School | ||||||

|

Academic failure beginning in late elementary school |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

Lack of commitment to school |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Family | ||||||

|

Family history of problem behavior |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

Family management problems |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

Family conflict |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

Favorable parental attitudes and involvement in problem behavior |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Peer and Individual | ||||||

|

Early, persistent antisocial behavior |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

Rebelliousness |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Friends engage in problem behavior |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

|

Gang involvement |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Favorable attitudes toward problem behavior |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

|

Early initiation of problem behavior |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

|

Constitutional factors |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

immersed in family, school, community, and peer environments that consistently communicate healthy beliefs and clear standards for behavior. When strong bonds exist between adolescents and prosocial individuals and groups, they are more likely to mirror prosocial beliefs and healthy behaviors. Bonds are fostered when young people are provided with opportunities to be involved in meaningful, developmentally appropriate activities, skills to be successful in those activities, and recognition for their efforts, achievements, and contributions to the group (Catalano et al., 1996).

CTC encourages community stakeholders to adopt the Social Development Model in their daily interactions with young people and to ensure that all young people are provided developmentally appropriate opportunities, skills, and recognition, as well as healthy standards for behavior. The Social Development Model also underlies community mobilization and training efforts. CTC creates opportunities for all interested stakeholders to participate in developing a shared vision for positive youth development based in prevention science. Diverse community representatives develop skills to work together effectively and are recognized for their efforts and contributions to positive youth development. Social bonds among coalition members enhance their commitment to implementing effective preventive interventions with fidelity.

Local control is built into CTC from the beginning. CTC guides communities to use the advances of prevention science, but community stakeholders determine which factors and outcomes to prioritize and which tested, effective programs and policies to implement to address their local concerns. Using CTC, it takes communities approximately 1 year to develop the skills and knowledge to choose and faithfully implement tested and effective prevention programs to address community priorities (see Box 8-1) (Hawkins et al., 2008b; Quinby et al., 2008). Implementation occurs

BOX 8-1

Communities That Care (CTC) Adds Value to

Evidence-Based Prevention Programs

CTC provides education, skills, and tools for building community capacity to change youth outcomes:

- CTC’s five-phase process provides communities with education and tools for assessing and prioritizing local risk, protection, and youth outcomes.

- CTC provides tools for assisting communities in matching prioritized risk and protective factors with tested, effective preventive interventions.

- CTC provides processes for enhancing fidelity in program implementation and engaging those targeted to receive the program.

in a series of five phases, each with specific milestones and benchmarks to be accomplished. Training and technical assistance are provided in each phase by a certified CTC trainer.

Phase 1: Get Started

In the first phase, community leaders concerned with preventing youth problem behaviors assess community readiness to adopt the CTC system, as well as local barriers to implementation. Successful implementation requires a shared belief in the utility of a preventive approach to addressing adolescent problem behaviors. Stakeholders should be willing to establish shared goals and collaborate to achieve them. If these attitudes are not present, readiness needs to be improved before implementing CTC. Other major activities include identifying one or two key leaders to champion CTC, hiring a coordinator to manage CTC activities, and obtaining school district support for conducting a youth survey that will provide local epidemiological data on risk, protection, and youth behaviors.

Phase 2: Organize, Introduce, and Involve

The major task in phase 2 is to identify and train two key groups of individuals from the community in the principles of prevention science and the CTC prevention system. The first group consists of key community leaders and influential stakeholders (mayor, police chief, school superintendent; business, faith, community, social service, and media leaders), who are introduced to CTC, prevention science principles, and the relationship between youth risk and protective factors and problem behaviors during a half-day Key Leader Orientation event. Key leaders are responsible for securing resources for preventive interventions and identifying candidates for the CTC Community Board, a demographically diverse and broad-based coalition that will carry out CTC planning and prevention activities. Board members participate in a 2-day Community Board Orientation to CTC. The board develops a vision statement to guide its prevention work and establishes work groups to perform core implementation and maintenance tasks: board maintenance, risk and protective factor assessment, resource assessment and analysis, public relations, youth involvement, and funding.

Phase 3: Develop a Community Profile

In phase 3, the CTC board develops a community profile of risk, protection, and problem behaviors among community youth; targets two to five risk and protective factors for preventive action; and identifies existing prevention resources and gaps. The first two activities are accomplished

in a 2-day Community Assessment Training. The major source of data for the community profile is the CTC Youth Survey (Arthur et al., 2007), a school-based self-report questionnaire administered to students in grades 6, 8, 10, and 12, focusing on risk and protective factors experienced by young people, as well as their involvement in problem behaviors such as substance use, delinquency, and violence. These data are supplemented by archival data (e.g., school dropout rates, teenage pregnancy statistics, arrest records). The resulting community profile provides baseline data against which change in targets can be evaluated. Following Community Resource Assessment Training, board members survey service providers to measure the extent to which high-quality, research-based prevention programs targeting local prioritized risk and protective factors are already available in the community and identify existing gaps. The community is educated about prevention resources, and parties are recognized for their contributions to positive youth development.

Phase 4: Create a Community Action Plan

In phase 4, board members use information gathered in phase 3 to develop a Community Action Plan. Two-day Community Plan Training provides tools and knowledge to select scientifically tested and effective programs, policies, and actions targeting local priorities and filling gaps in prevention services. The board chooses programs from the CTC Prevention Strategies Guide, a compendium of prevention programs (including parenting skills, school curricula, mentoring, after-school, and community-based programs) found effective in changing risk, protection, and problem behaviors in at least one high-quality controlled trial. The Community Action Plan specifies plans for implementing prevention programs, monitoring implementation quality, and assessing improvement in risk, protection, and problem behaviors.

Phase 5: Implement and Evaluate Community Action Plan

The last phase consists of implementing the Community Action Plan. Community Plan Implementation Training emphasizes the importance of adhering faithfully to the content, dosage, and manner of delivery specified in program protocols. Prevention program developers provide additional training and technical assistance. Board members and program implementers learn to track implementation progress, assess changes in participants, and make adjustments to achieve program objectives. Monitoring is accomplished through the use of program-specific implementation checklists, observations, and participant pre- and post-tests. During this phase, the

board also engages local media to educate the community about risk and protective factors for adolescent problem behavior and generate public support for the new preventive interventions.

When they complete phase 5, communities have the knowledge, tools, and skills to faithfully implement tested and effective prevention policies and programs to address locally prioritized risk, protection, and youth behaviors. However, the CTC process is ongoing. Every 2 years, the CTC Youth Survey is re-administered, and other community assessment data are updated. The CTC board reviews these data to evaluate progress and revise action plans as needed.

How Long Does It Take to Achieve Change in Risk, Protection, and Youth Outcomes?

Community-level changes in youth risk and protection are expected to occur 2 to 5 years after tested and effective prevention programs are implemented. Community-level effects on youth behaviors are expected 4 to 10 years following implementation.

CTC Works in Communities of Varied Size

A CTC “community” is a geographically specific place large enough for educational and human services to be delivered at that level. It can be an incorporated town or suburb or a neighborhood or school catchment area of a large city. The population of the area served should range from 5,000 to 50,000. In large cities, local CTC coalitions may be created to plan and implement preventive interventions for their own neighborhoods or school catchment areas.

The Community Youth Development Study: A Test of CTC

CTC has been evaluated in the Community Youth Development Study (CYDS), a multisite community-randomized trial initiated in 2003 involving 24 communities randomly assigned to receive CTC or to serve as controls in seven states across the United States. A longitudinal panel of 4,407 children has been surveyed annually from grades 5 through 10, 1 year after intervention support for CTC ended, so that the sustainability of the CTC prevention system and effects on youth outcomes could be evaluated. Effects on community prevention systems were evaluated using reports of key leaders from CTC and control communities. Effects on youth risk and problem behaviors were evaluated using the CTC Youth Survey. Major findings are summarized in Box 8-2.

BOX 8-2

Major Findings from the Community

Youth Development Study (CYDS)

Sustained prevention system effects. Four years after the start of the CYDS, Communities That Care (CTC) communities were significantly more likely to have adopted a science-based approach to prevention, to have implemented evidence-based prevention programs aimed at targeted risk and protective factors, and to be monitoring the impact of these programs. These differences were sustained 1 year after the intervention phase of CYDS had ended.

Exposure to targeted risk factors increased significantly less rapidly in panel youth in CTC communities than in control communities through grade 10, and levels of exposure to targeted risk factors were significantly lower in the panel in CTC communities than in control communities in the spring of grade 10.

Sustained prevention of delinquency and substance use. By spring of grade 8, youth in the longitudinal panel from CTC communities were 33 percent less likely to have initiated cigarette use, 32 percent less likely to have initiated alcohol use, and 25 percent less likely to have initiated delinquent behavior than youth in the longitudinal panel from control communities. By spring of grade 10, they were 28 percent less likely to have initiated cigarette use, 29 percent less likely to have initiated alcohol use, and 17 percent less likely to have initiated delinquent behavior than youth in the longitudinal panel from control communities. Fewer had engaged in violence in grade 10.

Universal effects. By grade 8, CTC reduced the prevalence of substance use and delinquency equally across risk-related subgroups and gender, with minor exceptions, indicating that CTC’s effects are universal.

Cost-beneficial investment. By preventing tobacco use and delinquency in grade 8, CTC returns $5.30 to society for every $1.00 invested.

Communities Can Faithfully Implement the CTC

Prevention System and Prevention Programs

The CYDS evaluated community efforts to faithfully implement the core principles of the CTC prevention system and of tested and effective prevention programs with respect to content and delivery specifications. The study found that CTC communities achieved high implementation fidelity at the system and program levels when supported by training and technical assistance in CTC. Control communities did not achieve these goals.

High-Fidelity Implementation of the CTC Prevention System

At the start of the CYDS, CTC and control communities did not differ in their use of a science-based approach to prevention (Hawkins et al., 2008a,b). By the third year of the intervention, key leaders in CTC communities reported a higher stage of adoption of science-based prevention, relative to control communities (Brown et al., 2011). They also were willing to provide greater funding for prevention. The CTC Milestones and Benchmarks Survey was used to track progress in the implementation of core components of the CTC prevention system. In each year of the intervention, CTC communities enacted an average of 90 percent of the key features of the CTC prevention system, including developing a community board, prioritizing risk and protective factors, selecting tested and effective preventive interventions from the CTC Prevention Strategies Guide, carrying out selected implementation programs with fidelity, and periodically assessing risk and protective factors and child and adolescent well-being through surveys of students (Fagan et al., 2009; Quinby et al., 2008). Control communities did not make this progress over time in completing CTC milestones and benchmarks, implementing scientifically proven prevention programs, or monitoring program impacts (Arthur et al., 2010).

Faithful Implementation of Tested and Effective Prevention Programs

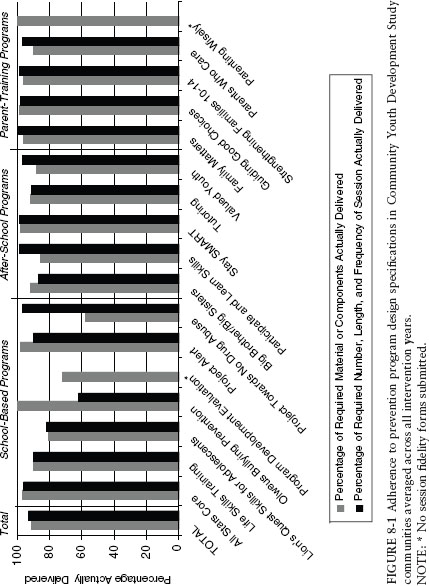

Over the course of the trial, the 12 CTC communities demonstrated faithful implementation of 17 different school-based, after-school, and parenting interventions (see Figure 8-1), selected from a menu of 39 possible tested and effective programs for fifth through ninth grade students contained in the Communities That Care Prevention Strategies Guide (Fagan et al., 2008, 2009, in review). On average, CTC communities implemented 2.75 tested and effective prevention programs per year (range: 1-5). High rates of fidelity were achieved consistently over time with respect to adherence to program objectives and core components (average = 91-94 percent per year) and dosage (number, length, and frequency of intervention sessions; average = 93-95 percent per year).

CTC Leads to Sustained Prevention of Youth

Risk, Delinquency, and Substance Use

CTC communities prioritized two to five risk factors to be targeted by tested and effective prevention programs (shown in Table 8-2). Effects on youth risk and problem behaviors were first observed in grade 7, after less than 2 full years of intervention and earlier than CTC’s theory of change suggested. Effects have been sustained through grade 10, 1 year after the trial’s intervention phase ended.

FIGURE 8-1 Adherence to prevention program design specifications in Community Youth Development Study communities averaged across all intervention years. NOTE: * No session fidelity forms submitted.

TABLE 8-2 Risk Factors Targeted by Community Youth Development Study Communities

| Domain and Risk Factor | No. of Communities |

| Community | |

| Laws and norms favorable to drug use | 1 |

| School | |

| Low commitment to school | 9 |

| Academic failure | 5 |

| Family | |

| Family conflict | 3 |

| Poor family management | 4 |

| Parental attitudes favorable to problem behavior | 1 |

| Peer | |

| Antisocial friends | 7 |

| Peer rewards for antisocial behavior | 2 |

| Individual | |

| Attitudes favorable to antisocial behavior | 3 |

| Rebelliousness | 3 |

| Low perceived risk of drug use | 2 |

Effects on Risk Factor Exposure

The longitudinal panel youth in CTC and control communities reported similar levels of targeted risk in grade 5, when the intervention began (Hawkins et al., 2008a), but targeted risk exposure grew more slowly for adolescents in CTC communities between grades 5 and 10 (Hawkins et al., in review). Significantly lower levels of targeted risk were first reported by CTC panel youth 1.67 years into the intervention in grade 7 and have continued to be reported by CTC panel youth through grade 10.

Preventive Effects on the Initiation of Delinquency and Substance Use

Panel youth from CTC and control communities also reported similar levels of delinquency, alcohol use, and cigarette smoking at grade 5 baseline. However, between grades 5 and 10, CTC had significant effects on the initiation of these behaviors by young people. Significant differences in the initiation of delinquency were first observed in the spring of grade 7. Panel youth from CTC communities were 25 percent less likely than panel youth from control communities to initiate delinquent behavior, and they remained so in grade 8. Significantly lower delinquency initiation rates were sustained through grade 10 (Hawkins et al., in review), when panel youth

from CTC communities were 17 percent less likely to initiate delinquency than panel youth from control communities.

Preventive effects on alcohol use and cigarette use were first observed in the spring of grade 8, 2.67 years after intervention programs were implemented. Grade 8 youth from CTC communities were 32 percent less likely to initiate alcohol use and 33 percent less likely to initiate cigarette smoking than grade 8 youth from control communities (Hawkins et al., 2009). Preventive effects were again sustained through grade 10 (Hawkins et al., in review), when CTC panel youth were 29 percent less likely to initiate alcohol use and 28 percent less likely to initiate cigarette smoking than panel youth from control communities.

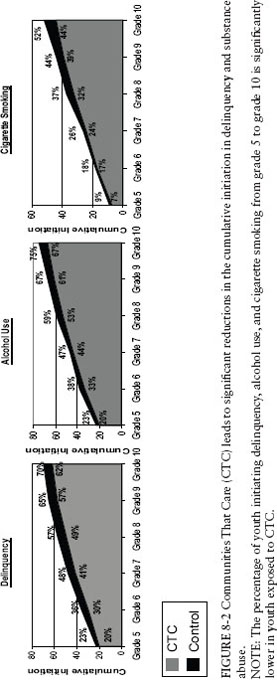

Differences in the initiation of delinquency, alcohol use, and cigarette smoking from grades 5 through 10 led to cumulatively lower rates of initiation over time (see Figure 8-2): 62 percent of 10th-grade youth in the panel from CTC communities had engaged in delinquent behavior compared with 70 percent of 10th-grade youth in the panel from control communities; 67 percent versus 75 percent had initiated alcohol use; and 44 percent versus 52 percent had smoked cigarettes.

Reductions in the Prevalence of Delinquency, Violence, and Substance Use

CTC also significantly reduced the prevalence of youth problem behaviors in grade 8 and grade 10. In grade 8, the prevalence of alcohol use in the past month, binge drinking (five or more drinks in a row) in the past 2 weeks, and the variety of delinquent behaviors committed in the past year were all significantly lower in CTC panel youth compared to control community panel youth (Hawkins et al., 2009). A subset of the delinquency items was used to create a measure of violent behavior in the fifth grade (attacking someone with intent to harm; range 0 to 1) and the 10th grade (attacking someone with intent to harm, carrying a gun to school, beating somebody up; range from 0 to 3). The CYDS found significant effects of CTC in reducing the prevalence of delinquent behavior and violence in the past year in the spring of grade 10 (Hawkins et al., in review). Tenth-grade students in CTC communities had 17 percent lower odds of reporting any delinquent behavior in the past year (t (9) = —2.33; p = .04; AOR [adjusted odds ratio] = .83) and 25 percent lower odds of reporting any violent behavior in the past year (t (9) = —2.51; p = .03; AOR = .75) compared to students in control communities.

CTC Is a Cost-Beneficial Intervention

A cost-benefit analysis was undertaken to determine whether CTC is a sound investment of public dollars, based on significant preventive effects

FIGURE 8-2 Communities That Care (CTC) leads to significant reductions in the cumulative initiation in delinquency and substance abuse. NOTE: The percentage of youth initiating delinquency, alcohol use, and cigarette smoking from grade 5 to grade 10 is significantly lower in youth exposed to CTC.

on cigarette smoking and delinquency initiation found in grade 8 (Kuklinski et al., in review). CTC’s long-term financial benefits from reducing initiation were compared to a very conservative CTC implementation cost of $991 per youth over 5 years. CTC was estimated to lead to $5,250 in benefits per youth, including $812 from the prevention of cigarette smoking and $4,438 from the prevention of delinquency. The benefit-cost ratio indicates a return of $5.30 per $1.00 invested, evidence that CTC is a cost-beneficial investment (Kuklinski et al., in review).

CTC is currently being implemented in more than 500 communities across the United States and in countries including Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.

Dissemination of CTC

All manuals and materials needed to implement CTC have been placed in the public domain by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and can be found at http://www.communitiesthatcare.net. In addition, it is clear from the Community Youth Development Study that high-quality training and technical assistance are important to ensuring successful implementation of CTC with fidelity.

CTC Guiding Principles

- Increase the use of tested and effective prevention policies and programs, while recognizing that communities are different and need to decide locally what policies and programs to use.

- Identify and prioritize locally specific elevated risk factors, depressed protective factors, and youth problem behaviors.

- Match tested, effective prevention programs and policies to priorities, and implement them with fidelity.

- Measure progress periodically, and make any needed adjustments.

Key Youth Outcomes

A randomized controlled trial of CTC showed that grade 8 youth exposed to CTC fared significantly better than youth not exposed to CTC:

- Risk factors targeted for intervention increased less rapidly from grades 5 to 8.

- CTC youth were 33 percent less likely to start smoking cigarettes, 32 percent less likely to start drinking, and 25 percent less likely to start engaging in delinquent behavior.

- The intervention was found to be cost-effective returning $5.30 for every dollar invested.

- These improvements have been sustained through grade 10, 1 year after study support to communities ended.

- Effects on the prevalence of substance use and delinquency were generally universal, applying equally to girls and boys as well as youth who differed in risk.

REFERENCES

Alvarez, J., J. Pavao, N. Baumrind, and R. Kimerling. 2007. The relationship between child abuse and adult obesity among California women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 33(1):28-33.

Apter, A. J., L. A. Garcia, R. C. Boyd, X. M. Wang, D. K. Bogen, and T. Ten Have. 2010. Exposure to community violence is associated with asthma hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 126(3):552-557.

Arthur, M. W., J. S. Briney, J. D. Hawkins, R. D. Abbott, B. L. Brooke-Weiss, and R. F. Catalano. 2007. Measuring risk and protection in communities using the Communities That Care youth survey. Evaluation and Program Planning. Pp. 197-211.

Arthur, M. W., J. D. Hawkins, E. C. Brown, J. S. Briney, S. Oesterle, and R. D. Abbott. 2010. Implementation of the Communities That Care prevention system by coalitions in the Community Youth Development Study. Journal of Community Psychology 38:245-258.

Bennett, G. G., L. H. McNeill, K. Y. Wolin, D. T. Duncan, E. Puleo, and K. M. Emmons. 2007. Safe to walk? Neighborhood safety and physical activity among public housing residents. PloS Medicine 4(10):1599-1607.

Bollinger, C. R., and K. R. Ihlanfeldt. 2003. The intraurban spatial distribution of employment: Which government interventions make a difference? Journal of Urban Economics 53(3):396-412.

Boynton-Jarrett, R., J. Fargnoli, S. F. Suglia, B. Zuckerman, and R. J. Wright. 2010. Association between maternal intimate partner violence and incident obesity in preschool-aged children: Results from the fragile families and child well-being study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 164(6):540-546.

Brown, E. C, J. D. Hawkins, M. W. Arthur, J. S. Briney, and A. A. Fagan. 2011. Prevention service system transformation using Communities That Care. Journal of Community Psychology 39:183-201.

Burdette, H. L., T. A. Wadden, and R. C. Whitaker. 2006. Neighborhood safety, collective efficacy, and obesity in women with young children. Obesity 14(3):518-525.

Campbell, J. C. 2002. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 359(9314): 1331-1336.

Carver, A., A. Timperio, and D. Crawford. 2008. Perceptions of neighborhood safety and physical activity among youth: The CLAN study. Journal of Physical Activity & Health 5(3):430-444.

Catalano, R. F., R. Kosterman, J. D. Hawkins, M. D. Newcomb, and R. D. Abbott. 1996. Modeling the etiology of adolescent substance use: A test of the social development model. Journal of Drug Issues 26(2):429-455.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1999. Neighborhood safety and the prevalence of physical inactivity—Selected states, 1996. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 48(07):143-146.

CDC. 2007. The cost of violence in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Centers for Injury Prevention and Control.

CDC. 2010. Youth violence: Facts at a glance. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/YV-DataSheet-a.pdf (accessed 2011).

CDC. 2011. Cost of violent deaths in the United States, 2005. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/violentdeaths/ (accessed 2011).

Chilton, M., and S. Booth. 2007. Hunger of the body and hunger of the mind: African-American women’s perceptions of food insecurity, health and violence. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 39(3):116-125.

City of Minneapolis. 2011. US Attorney General Holder lauds Minneapolis’ youth violence prevention initiative. http://www.ci.minneapolis.mn.us/news/20110527YthViolencePrevention_Holder.asp (accessed 2011).

Clark, C., L. Ryan, I. Kawachi, M. J. Canner, L. Berkman, and R. J. Wright. 2008. Witnessing community violence in residential neighborhoods: A mental health hazard for urban women. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 85(1):22-38.

Corso, P., J. Mercy, T. Simon, E. Finkelstein, and T. Miller. 2007. Medical costs and productivity losses due to interpersonal and self-directed violence in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 32(6):474-482.

Cradock, A. L., I. Kawachi, G. A. Colditz, S. L. Gortmaker, and S. L. Buka. 2009. Neighborhood social cohesion and youth participation in physical activity in Chicago. Social Science & Medicine 68(3):427-435.

Curry, A., C. Latkin, and M. Davey-Rothwell. 2008. Pathways to depression: The impact of neighborhood violent crime on inner-city residents in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Social Science & Medicine 67(1):23-30.

Eyler, A. A., D. Matson-Koffman, D. R. Young, S. Wilcox, J. Wilbur, J. L. Thompson, B. Sanderson, and K. R. Evenson. 2003. Quantitative study of correlates of physical activity in women from diverse racial/ethnic groups—The Women’s Cardiovascular Health Network Project—Summary and conclusions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 25(3):93-103.

Fagan, A. A., K. Hanson, J. D. Hawkins, and M. W. Arthur. 2008. Implementing effective community-based prevention programs in the Community Youth Development Study. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 6(3):256-278.

Fagan, A. A., K. Hanson, J. D. Hawkins, and M. W. Arthur. 2009. Translational research in action: Implementation of the Communities That Care prevention system in 12 communities. Journal of Community Psychology 37(7):809-829.

Fagan, A. A., M. W. Arthur, K. Hanson, J. S. Briney, and J. D. Hawkins. In review. Effects of Communities That Care on the adoption and implementation fidelity of evidence-based prevention programs in communities: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science.

Felitti, V. J. 2002. The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult health: Turning gold into lead. Zeitschrift Fur Psychosomatische Medizin Und Psychotherapie 48(4):359-369.

Felitti, V. J., R. F. Anda, D. Nordenberg, D. F. Williamson, A. M. Spitz, V. Edwards, M. P. Koss, and J. S. Marks. 1998. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults—The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14(4):245-258.

Fowler, P. J., C. J. Tompsett, J. M. Braciszewski, A. J. Jacques-Tiura, and B. B. Baltes. 2009. Community violence: A meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathology 21(1):227-259.

Frayne, S. M., K. M. Skinner, L. M. Sullivan, and K. M. Freund. 2003. Sexual assault while in the military: Violence as a predictor of cardiac risk? Violence and Victims 18(2): 219-225.

Fujiwara, T. 2008. Violence and asthma: A review. Environmental Health Insights 2:45-54.

Gomez, J. E., B. A. Johnson, M. Selva, and J. F. Sallis. 2004. Violent crime and outdoor physical activity among inner-city youth. Preventive Medicine 39(5):876-881.

Greenfield, E. A., and N. F. Marks. 2009. Violence from parents in childhood and obesity in adulthood: Using food in response to stress as a mediator of risk. Social Science & Medicine 68(5):791-798.

Hahn, R., D. Fuqua-Whitley, H. Wethington, J. Lowy, A. Crosby, M. Fullilove, R. Johnson, A. Liberman, E. Moscicki, L. Price, S. Snyder, F. Tuma, S. Cory, G. Stone, K. Mukhopadhaya, S. Chattopadhyay, and L. Dahlberg. 2007. Effectiveness of universal school-based programs to prevent violent and aggressive behavior: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 33(2 Suppl):S114-S129.

Harrison, R. A., I. Gemmell, and R. F. Heller. 2007. The population effect of crime and neighbourhood on physical activity: An analysis of 15,461 adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 61(1):34-39.

Hawkins, J. D., and R. F. Catalano. 1992. Communities That Care: Action for drug abuse prevention. The Jossey-Bass Behavioral Science Series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hawkins, J. D., E. C. Brown, S. Oesterle, M. W. Arthur, R. D. Abbott, and R. F. Catalano. 2008a. Early effects of Communities That Care on targeted risks and initiation of delinquent behavior and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health 43(1):15-22.

Hawkins, J. D., R. F. Catalano, M. W. Arthur, E. Egan, E. C. Brown, R. D. Abbott, and D. M. Murray. 2008b. Testing Communities That Care: The rationale, design and behavioral baseline equivalence of the Community Youth Development Study. Prevention Science 9(3):178-190.

Hawkins, J. D., S. Oesterle, E. C. Brown, M. W. Arthur, R. D. Abbott, A. A. Fagan, and R. F. Catalano. 2009. Results of a type 2 translational research trial to prevent adolescent drug use and delinquency: A test of Communities That Care. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 163(9):789-798.

Hawkins, J. D., S. Oesterle, E. C. Brown, K. C. Monahan, R. D. Abbott, M. W. Arthur, and R. F. Catalano. In review. Sustained decreases in risk exposure and youth problem behaviors after installation of the Communities That Care prevention system in a randomized trial.

Hogan, P., T. Dall, and P. Nikolov. 2003. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2002. Diabetes Care 26(3):917-932.

Huang, E. S., A. Basu, M. O’Grady, and J. C. Capretta. 2009. Projecting the future diabetes population: Size and related costs for the U.S. Diabetes Care 32(12):2225-2229.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2000. Promoting health: Intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Johnson, S. L., B. S. Solomon, W. C. Shields, E. M. McDonald, L. B. McKenzie, and A. C. Gielen. 2009. Neighborhood violence and its association with mothers’ health: Assessing the relative importance of perceived safety and exposure to violence. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 86(4):538-550.

Justice Policy Institute. 2009. The costs of confinement: Why good juvenile justice policies make good fiscal sense. Washington, DC: Justice Policy Institute.

Kilpatrick, D. G., K. J. Ruggiero, R. Acierno, B. E. Saunders, H. S. Resnick, and C. L. Best. 2003. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the national survey of adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71(4):692-700.

Kuklinski, M. R., J. S. Briney, J. D. Hawkins, and R. F. Catalano. In review. Cost-benefit analysis of Communities That Care outcomes at eighth grade.

Latkin, C. A., and A. D. Curry. 2003. Stressful neighborhoods and depression: A prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44(1):34-44.

Lehrer, E. 2000. Crime-fighting and urban renewal. Public Interest (141):91-103.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. 2006. Is it safe to walk? Neighborhood safety and security considerations and their effects on walking. Journal of Planning Literature 20(3):219-232.

Lumeng, J. C., D. Appugliese, H. J. Cabral, R. H. Bradley, and B. Zuckerman. 2006. Neighborhood safety and overweight status in children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 160(1):25-31.

Molnar, B. E., S. L. Gortmaker, F. C. Bull, and S. L. Buka. 2004. Unsafe to play? Neighborhood disorder and lack of safety predict reduced physical activity among urban children and adolescents. American Journal of Health Promotion 18(5):378-386.

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2003. Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

National Center for PTSD. 2007. How common is PTSD? http://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/pages/how-common-is-ptsd.asp (accessed 2011).

National Center for PTSD. 2009. PTSD in children and adolescents. Washington, DC: National Center for PTSD.

Neckerman, K. M., M. Bader, M. Purciel, and P. Yousefzadeh. 2009. Measuring food access in urban areas. New York: Columbia University.

Odoms-Young, A. M., S. Zenk, and M. Mason. 2009. Measuring food availability and access in African-American communities: Implications for intervention and policy. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36(4):S145-S150.

Paolucci, E. O., M. L. Genuis, and C. Violato. 2001. A meta-analysis of the published research on the effects of child sexual abuse. Journal of Psychology 135(1):17-36.

Pastore, D. R., M. Fisher, and S. B. Friedman. 1996. Violence and mental health problems among urban high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health 18(5):320-324.

Prevention Institute. 2010. Addressing the intersection: Preventing violence and promoting healthy eating and active living. Oakland, CA.

Prevention Institute. 2011a. City voices and perspectives: Blueprint for action—Preventing violence in Minneapolis. Oakland, CA.

Prevention Institute. 2011b. Unity fact sheet: Violence and chronic illness. Oakland, CA.

Prevention Institute, The California Endowment, The Urban Institute. 2007. Reducing health care costs through prevention. Oakland, CA.

Puzzanchera, C., and M. Sickmund. 2008. Juvenile court statistics 2005. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice.

Quinby, R. K., A. A. Fagan, K. Hanson, B. Brooke-Weiss, M. W. Arthur, and J. D. Hawkins. 2008. Installing the Communities That Care prevention system: Implementation progress and fidelity in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Community Psychology 36(3):313-332.

Rohrer, J. E., A. A. Arif, J. R. Pierce, Jr., and C. Blackburn. 2004. Unsafe neighborhoods, social group activity, and self-rated health. Journal of Public Health Managagement and Practice 10(2):124-129.

Rybak, R. T. P. 2011. State of the blueprint report. Paper presented at Blueprint for Action Youth Violence Prevention Conference, Minneapolis, MN, May 27.

Sallis, J. F., A. C. King, J. R. Sirard, and C. L. Albright. 2008. Perceived environmental predictors of physical activity over 6 months in adults: Activity counseling trial (vol. 26, p. 701, 2007). Health Psychology 27(2):214.

Schweinhart, L. J., J. Montie, Z. Xiang, W. S. Barnett, C. R. Belfield, and M. Nores. 2005. Lifetime effects: The High/Scope Perry preschool study through age 40. Ypsilanti, MI.

Shaffer, A. 2002. The persistence of L.A.’s grocery gap: The need for a new food policy and approach to market development. Los Angeles, CA: Center for Food and Justice, Urban and Environmental Policy Institute.

Shonkoff, J. P., W. T. Boyce, and B. S. McEwen. 2009. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities. Journal of the American Medical Association 301(21):2252-2259.

Skogan, W. G., S. M. Hartnett, N. Bump, and J. Dubois. 2008. Executive summary: Evaluation of CeaseFire-Chicago. Chicago, IL: Northwestern University.

Sternthal, M. J., H. J. Jun, F. Earls, and R. J. Wright. 2010. Community violence and urban childhood asthma: A multilevel analysis. European Respiratory Journal 36(6):1400-1409.

Suglia, S. F., M. B. Enlow, A. Kullowatz, and R. J. Wright. 2009. Maternal intimate partner violence and increased asthma incidence in children: Buffering effects of supportive care-giving. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 163(3):244-250.

Thorpe, K. E., C. S. Florence, and P. Joski. 2004. Which medical conditions account for the rise in health care spending? Health Affairs 23(5):W437-W445.

Vasquez, V. B., D. Lanza, S. Hennessey-Lavery, S. Facente, H. A. Halpin, and M. Minkler. 2007. Addressing food security through public policy action in a community-based participatory research partnership. Health Promotion Practice 8(4):342-349.

Veenema, T. G. 2001. Children’s exposure to community violence. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 33(2):167-173.

Vera Institute of Justice. 2011. Cost-benefit analysis. http://www.advanceproj.com/doc/p3_cost.pdf (accessed September 16, 2011).

Vest, J., and A. Valadez. 2005. Perceptions of neighborhood characteristics and leisure-time physical inactivity—Austin/Travis county, Texas, 2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 54(37):926-928.

Weir, L. A., D. Etelson, and D. A. Brand. 2006. Parents’ perceptions of neighborhood safety and children’s physical activity. Preventive Medicine 43(3):212-217.

Weiss, B., and Southern California Injury Prevention Research Center, UCLA School of Public Health, Prevention Institute. 2008. An assessment of youth violence prevention activities in USA cities. Oakland, CA: Prevention Institute.

Williamson, D. F., T. J. Thompson, R. F. Anda, W. H. Dietz, and V. Felitti. 2002. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. International Journal of Obesity 26(8):1075-1082.

Wilson, D. K., K. A. Kirtland, B. E. Ainsworth, and C. L. Addy. 2004. Socioeconomic status and perceptions of access and safety for physical activity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 28(1):20-28.

Wright, R. J., and S. F. Steinbach. 2001. Violence: An unrecognized environmental exposure that may contribute to greater asthma morbidity in high risk inner-city populations. Environmental Health Perspectives 109(10):1085-1089.

Wright, R. J., H. Mitchell, C. M. Visness, S. Cohen, J. Stout, R. Evans, and D. R. Gold. 2004. Community violence and asthma morbidity: The inner-city asthma study. American Journal of Public Health 94(4):625-632.

Yancey, A. K., and S. K. Kumanvika. 2007. Bridging the gap—Understanding the structure of social inequities in childhood obesity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 33(4):S172-S174.

Zenk, S. N., A. J. Schulz, B. A. Israel, S. A. James, S. M. Bao, and M. L. Wilson. 2005. Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. American Journal of Public Health 95(4):660-667.