The environment in which violence occurs affects the impact of and response to such violence. The ability to mobilize resources, support victims, address social norms, and recognize the role of early intervention differs across contexts and places. The presence of resiliency or other strong protective factors can mean less damaging impact and faster rebuilding. On the other hand, localities that are already fragile and under strain see more devastating effects of violence and often are trapped in repeated cycles of violence.

The first paper explores the role of social context in violence, particularly how certain communities are at risk of chronic violence. It defines concepts in a more general sense and is applicable in a number of settings.

The next three papers explore specific types of violence in specific settings. The second paper explores the impact of youth violence in conflict settings, particularly in Sierra Leone, and the reintegration of such youth post-conflict. The third paper examines the costs of intimate partner violence in three locations—Bangladesh, Morocco, and Uganda—and the similarities and differences between these settings. The final paper examines the intersection of youth violence and narcotics-related violence in Jamaica.

Mindy Thompson Fullilove, M.D., and Rodrick Wallace, Ph.D.

New York State Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University

Abe Lincoln may have freed all men, but Sam Colt made them equal.

—Slogan of Colt Manufacturing

Violence is part of human relationships. Several lines of inquiry link violence to social context. Structural violence describes the ways in which standing forms of social organization limit opportunity for some members of society. Structural violence, because it is part of the social order and standing law, is often considered “right” or “natural.” Criminal violence describes the harms that are done in violation of societal laws. Because this violence breaks the laws, it is hidden from view and punished on discovery. All societies suffer from some level of both of these kinds of violence, and the efforts at collective well-being are directed at exposing and correcting the harms that are hidden from view.

Epidemic violence refers to outbreaks of violence that are substantially in excess of the usual rates; epidemic violence might be either structural (state-sponsored genocide, for example) or criminal (as in an outbreak of drug-related violence). It is this third type, epidemic violence, that becomes problematic to the survival of society especially if the rates are elevated over long periods of time. The 2011 World Development Report puts these issues into stark relief. The report analyzed the problems of countries that are plagued by high levels of violence persisting over many years. It noted (World Bank, 2011):

No low-income fragile or conflict-affected country has yet achieved a single [UN Millennium Development Goal]. People in fragile and conflict-affected states are more than twice as likely to be undernourished as those in other developing countries, more than three times as likely to be unable to send their children to school, twice as likely to see their children die before age five, and more than twice as likely to lack clean water. On average, a country that experienced major violence over the period from 1981 to 2005 has a poverty rate 21 percentage points higher than a country that saw no violence.

The report also emphasized that problems in conflict-affected countries affect other parts of the country, lowering their productivity and destabilizing their social organization. Thus, the problem of chronic violence poses a serious threat to the survival of people and their societies. It emphasizes that “insecurity … has become a primary development challenge of our time” (World Bank, 2011). Yet overcoming chronic violence is difficult and takes, optimistically, a generation to accomplish. What has happened in social contexts that leads to such chronic violence and makes recovery so difficult?

Transformation of State

A modest paper by phenomenologist Eva-Maria Simms of Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, offers a useful insight into this

problem. Simms interviewed 12 people who grew up in the Hill District, an African-American working class neighborhood in Pittsburgh. She was struck by the differences in the accounts of childhood that were presented by the interviewees. She divided the responses into three eras. The first, which spanned 1930-1960, was characterized by tight social relationships in which all the adults collaboratively raised all of the children, who themselves were collaboratively engaged in exploring the many opportunities and dangers of the neighborhood. Urban renewal implemented in the late 1950s destroyed the major commercial section of the neighborhood, which had served as a connector to Pittsburgh’s downtown. This caused the destruction of many homes and businesses and dispersed many of the area residents. People growing up in the Hill between 1960 and 1980 were raised in smaller, though still substantial, networks. They had less sense of security. During that period, deindustrialization eliminated many of the employment opportunities for Hill residents (Simms, 2008).

Those growing up or raising children between 1980 and 2004 described living in a very fragmented place. The networks had shrunk, often only a single mother overseeing the care of children. The young people confronted violence and danger in the neighborhood, what one respondent called “unexpectancy.” The lack of predictability dictated self-protective behaviors for anyone needing to travel outside the home. This state of vigilance and self-reliance was in stark contrast to the earlier descriptions of interdependence and reliability (Simms, 2008).

The changes in social organization, interpersonal relationships, and views of the environment indicate a change of state in the place. Deborah Wallace, in discussing findings on low birth weight in another destabilized African-American community, noted (Wallace, 2011):

Ecosystem resilience theory can help interpret the results…. Holling articulated this theory in 1973 to explain how ecosystems deal with impacts and why they suddenly without warning may shift into an entirely different structure and function … impacts become amplified … and eventually cause a “domain shift.” (Holling’s term)

The change of state, or domain shift, appears to be accompanied by a shift in the behavioral repertoire of the inhabitants of the place. Acker examined the incursion of crack cocaine into the Hill district. She argued that losses of business and population due to urban renewal and deindustrialization devastated the Hill. The twin attractions of a new form of cocaine and a new source of money triggered the kind of epidemic of drug use that had been seen in other cities. The attractions for young men, in particular, to affirm their identities by selling crack, were irresistible for many. Following the logic of Bourgois (1995), who studied Puerto

Rican crack dealers in New York, Acker asserted, “In this world of dealing with its imperative of violence, these young men enacted a masculine identity that was denied them in the world of legitimate employment” (Acker, 2010).

Other researchers, observing the violence epidemic that accompanied the crack cocaine epidemic, reaching a peak between 1985 and 1995, found that the violence was used to define and protect territory and ensure reliability in black market transactions. The violence pervaded community life and was part and parcel of an emerging ethos of hyperindividualism in sharp contrast to earlier communitarian values.

Rodrick Wallace and colleagues, observing the violence epidemic at its peak, were struck, as Acker, Bourgois, and others had been, by the “imperative of violence.” He used mathematical models to examine the idea that violence, despite its high risk, was part of an emerging “language” that was effective under the conditions of social disintegration caused by deindustrialization and displacement (Wallace and Fullilove, 2008). Donaldson, a journalist studying minority neighborhoods in New York at that time, was able to document the “language” of violence that was being used (Donaldson, 1993).

Wallace and colleagues noted (1996):

The use of guns in the course of violent displays is a behavior that appears to conform to traditional norms. However, the lethality of guns increases the harm that will occur and undermines the possibility that the encounter will bring men together. For example, the gun, which has been called the “great equalizer,” enhances the power of the individual wielding it, without regard for the social norms for conferring power. A teenager with a gun becomes more powerful than an older man without one. The widespread adoption of guns by teenagers in inner-city communities, rather than conforming to established rules for displays of violence, has reconfigured them around gun-related dynamics. Young teenagers are clear that without a gun they feel exposed. The rate of weapon carrying has risen precipitously. As more and more young people are armed, more feel the need to be armed. With the rise of lethal weapons has come an inevitable rise in injuries and deaths.

Wallace et al. (1996) also noted, “There are, of course, possible applications to many regions of the world where ‘cycles of violence’ seem to have become established.” In particular, the article suggests that change of social state—a domain shift—from interdependence to hyperindividualism includes a shift toward the use of violence as an essential tool of communication and social control. This, in turn, creates a negative feedback loop that further undermines the social organization through exacerbating violence, causing injury and death, and preventing social progress.

Exiting Chronic Violence

Marginalization, inequality, and lack of economic opportunity are highlighted by the authors cited here as triggering and sustaining violence. Exiting from the feedback loop of chronic violence requires restoring confidence in collective organizations and creating opportunity for social and economic engagement with the larger society. The World Bank emphasizes two facts about this: (1) the World Bank has observed societies that have exited from chronic violence; (2) it notes that succeeding in such a process requires an array of social, justice, and financial interventions over a sustained period of time (World Bank, 2011).

Such progress is constantly threatened by economic, social, and environmental perturbations that disturb the social ecology of a recovering place. Drought, recession, and social disorder can undo progress, but concerted policies of serial forced displacement, as described for the United States by Wallace and Fullilove (2008), will be particularly effective in precluding community reknitting and recovery from the cycle of violence.

Despite the fragility of the situation, a broad consensus about the direction for the future will help people remain focused on the road to peace through difficult times. Sam Colt’s gun is one way of equalizing human populations: we can choose another way.

Theresa S. Betancourt, Sc.D., M.A.

François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights,

Harvard School of Public Health

Abstract

This paper concentrates on the psychosocial and developmental consequences of war experiences for child development and mental health using examples from a longitudinal study in Sierra Leone, West Africa. In war-affected countries, there is often an overlap of several forms of adversity commonly characterizing large proportions of developing children and their caregivers. As opposed to a simplistic view of children and violence that ascribes their long-term well-being as mainly linked to traumatic exposures or individual characteristics, a developmental and ecological lens is used to consider the many ways in which mental health and well-being are shaped by the interplay between individual, family, community, and societal

factors. The paper concludes with a series of recommendations illustrating the interplay between building the evidence base, increasing political will to make change, and improving the implementation of high-quality and sustain able services for children, youth, and families.

Understanding Children’s Experience of War

The mental health of young people affected by war-related violence and loss is a topic of increasing relevance to global public health (Jacob et al., 2007; Lancet Global Mental Health Group et al., 2007; Patel et al., 2007a,b; Prince et al., 2007; Saraceno et al., 2007; Saxena et al., 2007). Today, more than 1 billion children worldwide live in areas affected by armed conflict. Of these children, 30 percent are below the age of 5 (UNICEF, 2009). Situations such as armed conflict had contributed to the displacement of an estimated 18 million children as of 2006, including 5.8 million child refugees and 8.8 million children internally displaced within their own countries (UNICEF, 2008, 2009). Additionally, conflicts over the past decade have caused an estimated 2 million child deaths and left another 6 million children disabled (UNICEF, 2006). It is estimated that 1 million children over the last decade have been orphaned or separated from their families (UNICEF, 2007a). Since 1990, an estimated 90 percent of global conflict-related deaths have been civilians, with women and children accounting for four out of five of these deaths (Otunnu, 2002). In countries recently affected by conflict, the median adjusted maternal mortality was 1,000 out of 100,000 births compared to 690 out of 100,000 in countries without recent conflict (O’Hare and Southall, 2007). The toxic influence of armed conflict on child well-being is undeniable. Out of the 10 countries with the highest rates of under-5 deaths, seven are affected by armed conflict (UNICEF, 2007a).

War-Related Violence Damages the Social Environment

War dramatically undermines the many layers of the social ecology that normally support healthy child development and growth. War often heralds increased levels of poverty, weakened community structures, insufficient social services, economic devastation, and declines in health infrastructure (Guha-Sapir et al., 2005). Because of its broad impact on many other domains of human health and well-being, armed conflict is often viewed as a rate-limiting step in development progress. For example, of the 20 lowest-achieving countries across all the Millennium Development Goals, nearly half were affected by armed conflict (UNICEF, 2009). In particular, opportunities and services for children were dramatically more limited in areas affected by armed conflict; more than two-thirds of malnourished

children under age 5 live in war-affected countries (Southall and O’Hare, 2002; UNICEF, 2009).

Involvement with Armed Groups Has Profound Effects on Psychosocial Adjustment

Much attention has been paid to the involvement of children in armed conflict. Recently, it was estimated that approximately 300,000 boys and girls under the age of 18 were involved in 17 active armed conflicts around the world (Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers, 2008; UNICEF, 2007a). Children associated with armed forces and armed groups bear witness to violence and may take part in committing atrocities. Their connections to family and support networks are severed, leaving them to develop in unsafe and frightening environments. Studies have shown that children involved with armed forces and armed groups exhibit high rates of mental health problems and that their ability to navigate reintegration in post-conflict settings is limited by community stigma and difficulties in interpersonal relationships (Bayer et al., 2007; Betancourt et al., 2010a; Derluyn et al., 2004; Kohrt et al., 2008). In 2007, the Paris Principles: Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Conflict laid out comprehensive guidelines for preventing the engagement of children in armed conflict and for facilitating their reintegration in post-conflict settings (UNICEF, 2007b).

Of the studies conducted on these populations, several speak specifically to the psychosocial consequences of involvement with armed groups and outline the need for more integrated, robust community services for these young people. The longitudinal study presented in this paper underscores the complexities of post-conflict reintegration for war-affected youth.

The Value of an Ecological-Developmental Perspective

An intergenerational and ecological perspective is important for understanding the risk and protective factors that shape developmental and psychosocial trajectories of war-affected youth (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Among war-affected youth, resilience—defined as the ability to thrive and do well in spite of hardship—has most often been studied with a view toward individual qualities (Apfel and Simon, 1996). However, without considering the multiple layers of family, peer, and social influence that shape any one child’s mental health and well-being, these studies often take children out of context (Betancourt, 2011). A social-ecological view of resilience applies a broader perspective, looking to interactions between individual strengths, the social ecology, and resources in a child’s larger environment.

Overview of the Social Ecology

The work of Bronfenbrenner (1979) and later writings by Elbedour et al. (1993) and Betancourt and Kahn (2008) provide a foundation for considering the social ecology of child development in the context of compounded war-related violence and loss. Bronfenbrenner’s theory views individual aspects of the developing child, such as age, gender, temperament, or intelligence, as nested within a number of systems, including the “microsystem,” “mesosytem,” “exosystem,” and “macrosystem.” The microsystem encompasses different contexts (home, school, neighborhood) in which the child interacts with his or her immediate environment. The mesosystem is a larger system made up of more immediate microsystems and is implicated when two or more settings of relevance interact. This could include interactions between the child’s family and the school setting, such as the parent’s communication with the school, or between the child’s family and the extended social network, such as neighbor-to-neighbor interactions. Often, mesosystem interactions force children and adolescents to take on new roles and responsibilities; for example, a child may withdraw from school to care for younger siblings when the family is threatened by poverty or illness (Betancourt and Khan, 2008; Elbedour et al., 1993).

The exosystem is an extension of the mesosystem and includes societal structures, both formal and informal (e.g., religious and tribal bodies, government, major economic and cultural societal institutions). The exo-system pertains indirectly to the individual. For children facing adversity due to war-related violence, the exosystem may refer to the major actors who contribute to determining the conditions of aid and global economic development.

Finally, the macrosystem, or the larger cultural context including beliefs, customs, and the historical and political aspects of the social ecology, also has an important role to play. The macrosystem touches all other aspects of the social ecology and affects how different layers interact.

Applying the Social Ecology to Consider War-Affected Youth

For youth in settings of war or conflict, the importance of interactions across systems cannot be ignored. In these contexts, macrosystem-level issues such as governance and social investments take on particular importance. When applied appropriately, strong governance can exert influence on the functioning of community exosystems, including the services (e.g., schools) and protections (e.g., police) needed to enable positive child development (Aguilar and Retamal, 1998; Ungar et al., 2007). In turn, these community dynamics can bolster the family microsystems and

enable parents to best care for their children (Betancourt and Khan, 2008; Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Hobfoll et al., 1991).

Responses to the Situation of Children Affected by War

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

The United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) provides protection at the macro level and may be applied to strengthening exo-, meso-, and microsystems. The CRC speaks to the child’s right to protection from all forms of violence (Article 19) and exploitation (Articles 34-36), to life and maximum survival and development (Article 6), to an adequate standard of living (Article 27), and to health and education (Articles 24 and 28). The CRC also contains a series of special protection articles (Articles 19, 35, and 36) that address needed protections from physical or mental violence, injury, abuse or neglect, and exploitation (including sexual abuse), abduction, and trafficking. Specific to war, there are articles referring to the rights to protection for children who are refugees (Article 22), as well as those otherwise affected by armed conflict (Article 38) and a child’s right to physical and psychological recovery and social reintegration (Article 39). Similar protections are upheld in the African Charter on the Rights of the Child. Recent policy initiatives, such as the optional protocol to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, have called on member states to end the recruitment of children under age 18 into military forces (United Nations, 1989).

Reconciling Psychosocial and Clinical Responses

True realization of the CRC’s mandates, and Article 39 in particular, has been challenged by disagreement among humanitarian responders concerning appropriate treatment approaches to psychosocial and mental health issues in war-affected youth. Betancourt and Williams (2008) previously described the existence of two main approaches—psychosocial and psychiatric or clinical responses. Psychosocial approaches tend to focus on restoring the social and physical environment by reinvigorating indigenous coping mechanisms and implementing peer- and community-based activities. These interventions target a broad sample of beneficiaries rather than a population selected according to narrower diagnostic criteria. In contrast, psychiatric interventions aim to identify individuals who meet criteria for diagnosable mental disorders; these individuals are then given specific treatments targeted at reducing symptoms.

These two paradigms dominate the field but are often inappropriately set at odds with one another. In fact, population-level (psychosocial) and

individual-level (clinical) interventions can be viewed as complementary. As a first line of defense, psychosocial approaches to normalizing environment and day-to-day routines promote stability during crises and may be integrated with other exosystem health, social, and economic programs; clinical interventions then provide a second line of response to help individuals who demonstrate mental illness or profiles of risk. In an environment stabilized by psychosocial activities, these clinical practices can be better supported and more widely accepted by the community. This manner of operation is also reflective of an emerging science of prevention as underscored by a previous Institute of Medicine report (IOM, 1994).

Case Study: War-Affected Youth in Sierra Leone

The following case study examines these critical issues further. It presents a research project designed to examine how different layers of the social ecology affect child mental health and adjustment. Unique in its longitudinal design, this study followed youth across three time points as they adjusted to mesosystem interactions and macrosystem factors in a post-conflict setting. In considering the historical and political context of Sierra Leone, as well as more concrete factors that may be leveraged to improve opportunities open to youth, this study has important implications for designing holistic interventions for this and other war-affected populations.

Background: Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone’s 11-year civil conflict (1991-2002) involved a number of warring groups, including the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), the Sierra Leonean Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC), the Sierra Leone Army (SLA), and other local groups such as the Civil Defense Forces (CDF). During this period, tens of thousands of civilians were killed and roughly 75 percent of the population was displaced (Medeiros, 2007; Williamson and Cripe, 2002). A wide range of human rights abuses were documented, including mass mutilations and pervasive use of children in armed conflict. Estimates are that as many as 28,000 children were conscripted into fighting forces, some as young as 7 years of age (Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers, 2008; Mazurana and Carlson, 2006; World Revolution, 2001). While many were abducted into their role as child soldiers, other children chose to become involved, in part due to an extremely limited set of opportunities resulting from a breakdown in family and community systems as well as insufficient economic and educational opportunities (Ashby, 2002). As a result of their involvement with armed forces and groups, many youth witnessed and even perpetrated acts of intense physical and sexual violence, including executions, death squad killings, torture,

rape, detention, bombings, forced displacement, destruction of homes, and massacres. Throughout this time, these children were continually deprived of their rights to the protection of their families and were denied education and many basic physical needs, such as food, water, clothing, and shelter.

A Longitudinal Mixed-Methods Study (2002, 2004, 2008)

In 2002, this author launched a collaboration with the International Rescue Committee (IRC) to conduct a three-wave (T1, T2, T3) longitudinal study of former child soldiers and other war-affected youth in Sierra Leone (Betancourt, 2010; Betancourt et al., 2008, 2010a,b,c, 2011). The overall aim of the study was to examine how social reintegration and psychosocial adjustment in these youth were shaped by risk and protective factors. In line with its ecological-developmental view, the study examined issues such as age of involvement, experiences of loss and violence, family relationships, social support, and societal stigma (Betancourt and Khan, 2008). Other macro level factors included the challenges and successes that war-affected youth experienced in securing a livelihood, completing school, avoiding high-risk behavior, and contributing to civil society.

The study used a mixed-methods design, integrating both quantitative and qualitative methods over several periods of data collection. Qualitative data on local constructs of importance informed the development and selection of core constructs of interest for the quantitative survey. In T2 and T3, additional items were included to obtain more in-depth information on economic self-sufficiency, interpersonal relationships, intimate partner relationships and violence, child rearing and parenting, social capital, stigma and discrimination, HIV-risk behavior, drug and alcohol use, civic participation, and post-conflict hardships.

The sample cohort for the survey contained three main subgroups. The core sample comprised young people first surveyed as children formerly involved with the RUF that had been referred to the IRC’s Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) program in Sierra Leone’s Kono District for resettlement. The sample was drawn from a master list of IRC registries of all youth assisted by their Interim Care Center (ICC), which served five districts during the most active period of demobilization (June 2001 to February 2002). A list of 309 youth was reviewed to identify those who were aged 10 to 17 at time of release and for whom contact information was available. This yielded 259 youth (11 percent female) and their caregivers who were invited and agreed to participate in the baseline assessment. At that time, the team also conducted a random door-to-door sample of 10- to 18-year-olds not served by ICCs in the Kono district where the IRC center was based. A comparison group of children (n = 136, 29 percent female) who claimed to have not been involved with the RUF was

identified by random door-to-door sampling of male and female youth of similar age to the ICC-served group. During the second wave of data collection in 2004, a third group comprising 127 self-reintegrated youth (or youth who did not receive DDR services) was added.

Surveys were conducted among war-affected youth, their caregivers, and a comparison group at three times: 2002, 2004, and 2008. Additionally, a series of in-depth interviews with a subset of youth and their caregivers was completed in 2004 (T2) and 2008 (T3). A number of focus groups were also held in major resettlement communities with community members and youth, both those involved in armed groups and those not. All surveys and focus groups were conducted in the Krio language by trained Sierra Leonean research assistants.

Findings. This research has led to several publications about how war-related and post-conflict experiences affect the longer-term mental health and psychosocial adjustment of former child soldiers (Betancourt et al., 2008, 2010a,b,c, 2011, in press). One of the critical findings of the study is that the long-term mental health of former child soldiers is influenced not only by conflict-related exposures, but also by post-conflict contextual factors at multiple ecological levels. For example, lower levels of prosocial behavior over time were associated with experiencing stigma in the post-conflict environment, as well as with particularly toxic types of past war exposures (Betancourt et al., 2010a). Increases in anxiety and depression over time were closely related to social and economic hardships.

Of importance to programming and policy, the relationships between war-related exposures and poor adjustment were fully or partly mitigated by a range of post-conflict protective factors, including social support, family acceptance, being in school, and increases in community acceptance. Overall, community acceptance—both initially and over time—had beneficial effects on all outcomes studied. Importantly, qualitative data indicated that even young people who experienced extreme trauma could reintegrate well, in most cases, if they had strong family and community support and post-conflict opportunities, such as access to education. In contrast, youth who lacked strong, effective support were found to be on a much riskier path characterized by social isolation, high-risk behavior (e.g., substance abuse), and dangerous survival strategies (e.g., transactional sex).

Implications. This research provides new insights into the long-term well-being of children exposed to some of the most extreme violence imaginable. In this study, the family and community microsystems are highlighted as critical to supporting successful post-conflict reintegration. These findings are particularly compelling for researchers, practitioners, and policy makers, since many family and community factors can be modified through

intervention. In particular, research from this study underscores the importance of strengthening family support, as well as the need for sustainable exosystem and macro level interventions, including policies and programs to dispel community stigma.

The integration of these services into education programs and primary health care is important. Opportunities for promoting this integration are prime in Sierra Leone, where a new free child health initiative is increasing access for vulnerable families in many rural parts of the country. However, this initiative’s current focus on 0-5-year-olds will be insufficient to meet the needs of vulnerable youth and must also adapt to the evolving needs of an important population.

Addressing Consequences of

War-Related Violence and Loss for Children Globally

The reality of children affected by war and communal violence is widespread and not likely to subside for some time. This reality calls on all to apply their best efforts to address health and developmental challenges at many levels. Ecological and developmental approaches are fundamental to achieving integrated and effective responses, as demonstrated through the findings of the case study presented above.

Importantly, it is clear that maintaining resilience and strength in families across the span of childrearing is an important goal and need. For too long, programming for vulnerable children and families has been fragmented and characterized by a “silo” approach whereby major sectoral responses (health, education, security, employment) operate in isolation from one another. From a public health perspective, integrated, effective, and well-implemented systems of care, both formal and nonformal, are among the social foundations required to help vulnerable children and families overcome adversity (Beardslee, 1998; Beardslee and Gladstone, 2001).

Recommendations for Improving Services

To improve services for this population, a number of considerations must be taken into account. First, we must target high-impact issues with clearly designated, measurable outcomes in terms of both the physical health and the social, emotional, and cognitive development of children at risk. Second, we must develop multisectoral campaigns that address the entire social ecology, including factors such as health, education, social services, law enforcement, and finance. Third, we must operate strategically to link the science base closely to advocacy efforts. Such collaborations may be able to more efficiently translate data on child health and development into practice. Increasingly over time, these systems should become part of the health infrastructure. Finally, to make true advances in this field, we must marshal resources large

enough and over a long enough time to achieve the desired outcomes, develop sustainable systems of care, and monitor and evaluate those outcomes.

Future Directions

This paper has presented many of the key paradigms for considering the healthy development of children and families affected by violence globally. The discussion has also presented a field-based example that highlights the need for interventions that attend to the developing child’s social ecology. In conclusion, the importance of advancing a research agenda on children, youth, and families affected by violence and war cannot be stressed enough (Betancourt, 2011). By strengthening this evidence base, we may better achieve the CRC mandate to ensure the health, productivity, independence, and well-being of children through optimal rehabilitation. However, lack of financial support and mechanisms for collaboration impedes high-quality research. To ensure that such efforts are sustainable and can be scaled up over the long term, the international community and major humanitarian and scientific organizations have a tremendous role to play (MDRP, 2009; Patel et al., 2007b; Wessells, 2009a,b). Through investments in health and social services systems, the development and implementation of evidence-based services, capacity building, human resources development, and robust relationships with local initiatives and civil society, a more vigorous infrastructure to support the healthy development of all children affected by war and communal violence can be built.

INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE IN LOW- AND

MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES: HIGH COSTS TO

HOUSEHOLDS AND COMMUNITIES1,2

Aslihan Kes, M.S.

The International Center for Research on Women

Violence against women is globally acknowledged as a basic human rights violation and a fundamental obstacle to the achievement of gender equality. It also increasingly is seen as a development issue with severe consequences for economic growth.

___________________

1 This summary is drawn from an earlier ICRW publication: International Center for Research on Women. 2009. Intimate partner violence: High costs to households and communities. Policy Brief. Washington, DC: ICRW.

2 ICRW gratefully acknowledges the funding and support from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) for this project, which was implemented by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW); the Economic Policy Research Centre (EPRC) in Kampala, Uganda; the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS) in Dhaka; and Hassan II University Mohammedia-Casablanca in Morocco.

In a dynamic policy environment, strong evidence on the economic costs of violence against women is crucial to underscore the significant consequences of inaction. Though a number of studies have analyzed violence in terms of its direct and indirect costs, these analyses have been limited largely to developed countries. In developing countries, the few studies on the costs of violence have focused on the macro level, exploring costs to national governments rather than analyzing more immediate costs to individuals, households, and communities.

To fill this gap, the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and partners undertook a three-country study in Bangladesh, Morocco, and Uganda to estimate the costs of intimate partner violence at the household and community levels. The focus on intimate partner violence was motivated by the fact that this is the most common form of violence against women. A household and community-level analysis helps shed light on the relationship of intimate partner violence to both household economic vulnerability and the extent to which scarce public resources for essential health, security, and infrastructure services are diverted due to such violence.

Bangladesh, Morocco, and Uganda are particularly relevant countries for this study. Despite their diverse economic and social profiles, intimate partner violence is highly prevalent in all three countries. At the same time, recognizing the importance of a comprehensive response to intimate partner violence, these countries recently rolled out innovative programs, coupled with legislative initiatives, to address it.

Overall, the study suggests that intimate partner violence is pervasive and severe, most women who experience violence do not seek help, out-of-pocket costs to women and service providers are high, and indirect costs may dwarf direct costs. These findings join a growing body of evidence suggesting that violence against women is both a human rights violation and a drain on economic resources that reaches through households to communities and societies at large.

Overview of Study Methodology

The study applied an accounting methodology to estimate the direct costs of intimate partner violence at the household and community levels. Women’s experience of violence was measured using an adapted version of the instrument developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the multicountry study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Women were asked whether they experienced physical, emotional, or sexual intimate partner violence in the 12 months prior to the study; what the outcomes of each incident were; what services, if any were used; and the amount of money they spent to access these services. This information

was used to calculate the average total out-of-pocket cost to households of using any of these services due to intimate partner violence.

The community-level costs explored in the study consisted of costs incurred by various service providers in responding to cases of intimate partner violence. In Morocco and Uganda, these costs were calculated using a “unit cost” method. In each sector, the average total cost of providing services to a victim of intimate partner violence was multiplied by the estimated average number of victims registered in the 12 months prior to the study (average cost of service provision was estimated based on personnel hours and salary information). In Uganda, the number of intimate partner violence cases handled by each type of service was obtained from the providers. In Morocco, these numbers were estimated using women’s own reporting of service use due to an incident of intimate partner violence. In Bangladesh, the “proportionate” method was used, where the total cost of intimate partner violence to a provider was assumed to be proportional to the share of intimate partner violence cases received within 12 months prior to the study.

To estimate the indirect costs of intimate partner violence to households, women were asked about the work and time use related outcomes of each incident they experienced in the 12 months prior to the study. They were also asked about the impact the incident had on the spouse and others in the household. This information was intended to be used to estimate the value of productive time lost through additional use of actual or imputed wage information.

Study Sample

In each country, surveys were administered to randomly selected households and one eligible woman per household. The eligibility criteria for women was age (15+ in Morocco and Uganda; 15-49 in Bangladesh) and having been in a cohabitating relationship at the time or during the 12 months prior to the study. In cases where more than one eligible woman was in the household, one was selected randomly to be interviewed. The sample size was 2,003 in Bangladesh, 2,122 in Morocco, and 1,272 in Uganda.3,4

Through questionnaires and key informant interviews, data also were collected from select service providers in the health, criminal justice, social, and legal sectors (see Box 7-1).

___________________

3 The sample of women in Uganda was lower because the survey was administered to both men and women.

4 In Morocco and Uganda, samples were nationally representative. In Bangladesh, the sample was not.

BOX 7-1

Services Surveyed in Bangladesh, Morocco, and Uganda

Partners interviewed the following for each country study:

Bangladesh––7 health facilities, 10 police stations, 10 Salish, and 3 courts.

Morocco––2 health facilities, 2 police stations, 1 court, and 1 non-governmental organization.

Uganda––217 health facilities, 68 police stations, 54 probation offices, and 277 local councils.

Key Findings

In All Three Countries, Intimate Partner Violence Is Prevalent, Frequent, and Severe

In Uganda, about half of women report experiencing physical or sexual intimate partner violence in their lifetime and almost 30 percent have experienced both. In Bangladesh these percentages are even higher as observed in Table 7-1.

Women in all three countries report multiple incidents as well as multiple and severe forms of intimate partner violence. For example, in Morocco, about 46 percent of women who experienced physical violence report more than one incident. In Uganda, of the 1,193 incidents reported, 10 percent resulted in physical injury, including deep cuts, eye injuries, burns, and broken bones.

TABLE 7-1 Estimated Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence (percent)a

| Type | Bangladesh | Morocco | Uganda | |||

| Lifetime | Current | Lifetime | Current | Lifetime | Current | |

| Physical | 66 | 33 | 27 | 18 | 50 | 22 |

| Sexual | 61 | 38 | 20 | 15 | 47 | 28 |

| Physical and sexual | 46 | 18 | 15 | 11 | 29 | 12 |

| a Estimated prevalence rates of intimate partner violence for Morocco reported here are revised estimates and are different from those originally reported in the Policy Brief. | ||||||

The Majority of Women Who Experience Violence Do Not Seek Help

Only 17 percent of women in Morocco and 10 percent of women in Bangladesh used a health service at least once after being abused during the

12 months prior to the study; in Uganda, 11 percent of all reported violent incidents resulted in service use. Given the injuries women report, their use of health services appear to be lower than the actual need.

For a handful of women who experience violence in Bangladesh and Uganda, informal community structures are the first point of contact and recourse. In Uganda, women used the local council mechanism in 8.5 percent of all violent incidents, in contrast to 2 percent who reported using the police and 0.2 percent the formal justice system. Findings are similar in Bangladesh, where the local Salish works like the local councils.

Costs of Intimate Partner Violence to Households and Service Providers Are Significant

In Uganda, the average out-of-pocket expense for a violence incident is 11,337 Ugandan shillings (UGS), or $5, with police support costing nearly double that (17,904 UGS, or $10). In Morocco, use of the justice system is costliest (2,349 Moroccan dirham, or $274) followed by health (1,875 Moroccan dirham, or $211). When taken in the context of these countries’ gross national income (GNI) per capita in 2007—$340 in Uganda and $2,250 in Morocco, for example—the related costs for households are high.

Costs to service providers also are significant. Health providers report average labor costs of one intimate partner violence case at $1.20 in Uganda, $5.10 in Bangladesh, and $41 in Morocco. In Uganda, 68 percent of hospital providers surveyed report seeing at least one case of physical injury due to intimate partner violence each week. When personnel and other labor costs are taken into account, the estimated costs grow to $1.2 million annually.

The Indirect Costs of Intimate Partner Violence May Dwarf Direct Costs

In Uganda, about 12.5 percent of women report losing time from household work, especially washing clothes and fetching water and fuel wood, because of intimate partner violence. Nearly 10 percent of incidents resulted in women losing paid work days, an average of 11 days annually.

In Bangladesh, more than two-thirds of the study households reported that intimate partner violence affected a member’s work—both productive and reproductive. Using the average market wage rate of women with similar education, the average value of lost work per violent incident to households is estimated at about 340 Bangladeshi taka, or $5—4.5 percent (7,626 Bangladeshi taka, or $112) of the average monthly income of the households studied.

Conclusion

The direct and indirect costs of intimate partner violence are high for women, their families, communities, and nations. The cost findings from this study are especially alarming given the low rate at which women use formal, more costly services related to violence.

These findings also do not include the high costs of violence beyond immediate physical injuries. Physical and sexual violence increase women’s risk for a host of other serious conditions, including chronic pain, reproductive health problems, miscarriages, depression, and sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV. Intimate partner violence is also linked to maternal mortality and murders of women, as well as poor child health and mortality. These costs to society in terms of the global burden of ill health (measured by disability-adjusted life-years [DALYs]) and human development are enormous. These immediate and sustained costs and impacts of violence against women are significant impediments to the achievement of Millennium Development Goals; thus, its elimination must be a key development goal in itself.

Initiatives such as Bangladesh’s Multisectoral Program on Violence Against Women, Morocco’s recent national plan to address violence against women, and Uganda’s pending Domestic Violence Bill are a good start. Still more is needed. National governments and donors should provide support services for survivors of violence. Moreover, they should invest in informal dispute resolution mechanisms for women, including additional research to assess the effectiveness of these systems and ensure that they work for women.

Finally, in moving forward, potential areas of research include a more in-depth exploration of the nonmonetary impacts of intimate partner violence and the help-seeking behavior of women. It is also important that research is expanded to examine the cost-effectiveness of violence prevention programs.

YOUTH VIOLENCE IN KINGSTON, JAMAICA

Elizabeth Ward, M.B.B.S., M.Sc.

Institute of Criminal Justice and Security, and

Violence Prevention Alliance Jamaica

Damian Hutchinson, M.Sc.

Peace Management Initiative

Horace Levy, M.A.

Institute of Criminal Justice and Security

Deanna Ashley, M.B.B.S., D.M. (Paeds)

University of the West Indies at Mona

In recent years the Caribbean islands have been faced with rising homicide rates. In the Caribbean, Jamaica has the highest homicide rate at 53 per 100,000, followed by Belize at 42 per 100,000 and St. Kitts at 40 per

100,000. Trinidad’s homicide rate has risen to 36 per 100,000, five times the level it was in 1999. As violent deaths reach 5 percent of all deaths in the Caribbean, the effect on these small island states is enormous and has had a major impact on the health status of its youth. While resources are being focused on crime control, the role of prevention of violence needs to be brought to the forefront (Crime in the Caribbean, 2011).

In Jamaica, the impact of criminal violence on all facets of national life has been large-scale, and the country’s 2009 interim Millennium Development Goals report cites violence as a cross-cutting barrier preventing the achievement of the goals. The national response to violence still is focused on crime control, with a lackluster prevention response from all sectors. This paper addresses the impact of the epidemic of violence in Jamaica on its youth population, who bears the burden, and the costs of violence versus the benefits of investing in prevention.

Young people in Jamaica’s marginalized communities have fallen through the cracks. Local and international administrations, faced with budgetary constraints, have focused on the macroeconomic issues and neglected to protect them. Young people aged 15-24 years make up 17 percent of the population, or around half a million persons. These young people experience high rates of unemployment and teenage pregnancy and are often either victims of or major perpetrators of crime. In 2009, more than 50 percent of males arrested for major crimes were in the 15-24 age group, as were 11 percent of the victims (Planning Institute of Jamaica, 2010). Homicide is the leading cause of death among these males.

The Problem

While the focus of successive political administrations in Jamaica has been to equip young people with the requisite technical and vocational training and provide them with a protective environment to make the transition needed to adulthood, a wide gap exists between those needing and those accessing the services. Inner-city youth are born into, grow up in, and contribute to violence. They are easily sucked into gang and turf wars simply because they are from a particular area or linked with a certain group. This violence dominates the communities. Surveys among adolescents have shown that 5 out of every 10 adolescents (47.6 percent) had seen a dead body other than at a funeral (Samms-Vaughan et al., 2005). Survival in violent neighborhoods is important, and by age 15, 18 percent of school children reported carrying a weapon to school (Fox and Gordon-Strachan, 2007).

In addition to community violence, family violence is widespread. Prior to age 15, nearly one of five (18 percent) Jamaicans witnessed physical abuse between their parents and two-thirds (60 percent) experienced parental physical abuse. Women are disproportionately affected by intimate

partner violence (IPV) with one of five women (17 percent) reported as being victims of IPV, 15 percent of verbal abuse, 7 percent of physical violence, and 3 percent of forced sex with an intimate partner. Corporal punishment continues to be the dominant form of discipline in homes, as well as in schools (National Family Planning Board, 2010).

Educational attainment in this group is dismal, with 27 percent not completing more than grade 9 (Ministry of Education, 2010). Young people who fail to progress in school or drop out often are those who have been either suspended or expelled. Such disciplinary actions are the common methods of dealing with student drug use, gang membership, and fighting. The majority of gang members have a history of being suspended or expelled from school.

The majority of young people associated with gang activities are exposed to poor parenting, often with harsh, erratic discipline. Frequently, they are school dropouts—therefore functionally illiterate, with limited ability to reason—and turn readily to gun violence. As early entrants into the ranks of the unemployed except for menial tasks, they are excluded from mainstream life and see themselves as rejected by society. As “failures” and “losers” and in the absence of any meaningful program, they often develop a gangster lifestyle.

While national unemployment levels were 11.6 percent in October 2010, unemployment for young males and females was 22.5 percent and 33 percent, respectively (Planning Institute of Jamaica, 2010). As such, Jamaica has more than 127,000 young people described as unattached. “Unattached” describes a person who falls within the age group 15-24, is unemployed or outside the labor force, and is not in school or in training (Fox, 2003; HEART Trust-National Training Agency, 2009). Within this group are high-risk young people who are involved in crime, violence, and other negative gang-related activities; this group usually makes up 5 percent of the total youth population (Scott, 1998).

Unattached youth experience many problems. Studies of this population have identified that more than 76 percent had no academic qualifications and probably needed remedial education (HEART Trust-National Training Agency, 2009). Most of them come from low-income families in which basic necessities, fathers, a caring supportive person, and especially love are often in short supply. They look outside the family, like most young people anywhere, to peer groups for support (Levy, 2001; Moser and van Bronkhorst, 1999).

The Cycle: Youth Violence, Wounded Community, Battered Nation

The most pressing problem in Jamaica today is the high incidence of crime, violence, and moral breakdown, which, although a country-wide

problem, is particularly concentrated in inner-city areas. Hopelessness is pervasive among inner-city adolescents and youth. Their participation in the cycle of violence is often in gang and criminal activities for young men and various forms of prostitution for young women. In the case of young women, sex for financial gain, protection, and survival tends to result in wanted or unwanted pregnancies. As such, the cycle begins anew and is further perpetuated (Levy, 2001; Moser and van Bronkhorst, 1999).

The Role of Prevention

Not all young people growing up in inner-city Jamaica become involved in violence. In examining behavior in a Jamaican urban cohort, Samms-Vaughn et al. (2005) found that aggressive and delinquent behaviors were associated with underachievement, in addition to others factors; children displaying prosocial behavior came from stable family units that displayed affection and participated in organized activities. Looking at risk and protective factors, Fox and Wilks found similar results where exposure to caring relationships with responsible adults; high expectations; and meaningful participation in the home, schools, or the community prevented adolescents and youth from becoming involved in violent or delinquent behavior (Fox, 2003; Wilks et al., 2007).

Foundation for Prevention

Youth programs need to be built on a solid early childhood foundation. Throughout the world, parenting interventions, including home visitation for young children and interventions in preschool to reduce aggressive behavior, have been shown to be a cost-effective means of preventing violent behaviour (Hawkins, 2007).

Interventions that included weekly home visits by trained community health aides, with play sessions where praise was encouraged and physical punishment discouraged, showed that adults who had received these home visits as children reported less involvement in fights or more serious violent behavior (e.g., injuring someone with a weapon, gun use, gang membership) and had higher educational attainment (McGuire, 2008; Walker, 2011).

For the 10- to 14-year age group, school-based interventions are a method of reaching the 82 percent who attend school (Planning Institute of Jamaica, 2010). An active program for school retention is needed throughout the educational system to reduce the level of school dropouts by offering alternative educational and behavioral strategies along with financial support.

Youth Transition for High Risk Youths

Key components for transition for high-risk youths are

- High-risk youth transition programs,

- Foundation (parenting, life skills, literacy, relevant education),

- National Youth Club Movement,

- Consolidated youth programs,

- Youth empowerment officers (community based),

- Mentorship,

- Youth employment,

- Budget, and

- The will to bridge the gap.

Youth Empowerment Officers (YEOs) and PMI Program Implementers should be assigned, one to each community being targeted. YEOs are highly training to engage with youth directly. In marginalized Jamaican communities, young people are at high risk for violence and need tangible on-the-ground support to drive the transition process. The need for YEOs varies within individual communities: some communities may require more than one officer, or there may be a need to address a smaller number of communities or for groups of communities to receive shared services to achieve the desired change.

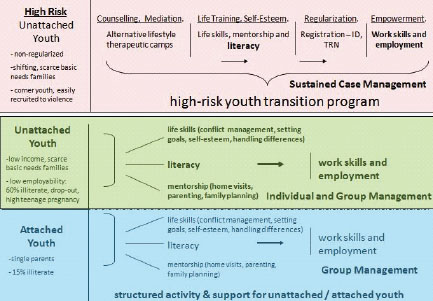

The PMI program implementer role would be to stabilize the high-risk youth communities by resolving disputes and mediating conflict. They would be in charge of the program for the high-risk unattached youth outlined in Figure 7-1. The PMI Zone Officers and Program Implementers would work with high-risk youth in collaboration with the YEOs, focusing on conflict mediation and monitoring the case files of at-risk youth.

The YEO would be community based but also linked to youth information centers. The YEO should have database information on the names and addresses of the youth in the community that are unemployed and unengaged, the number of youth who have dropped out of school, teenage mothers (Planning Institute of Jamaica, 2009) in the community, and so on. YEOs should have all the information needed to drive young people out of their current high-risk situation and into positive mainstream activity. They should be qualified to deal with young people affected by substance abuse, gangs, unemployment, peer pressure, broken homes, poor family environment, and ignorance, as well as being sufficiently aware of all the positive interventions available to young people affected by these issues.

Consolidate Youth-Oriented Institutions. The YEO would work with the consolidated youth institutions and would have to collaborate with the

FIGURE 7-1 Youth transition model. SOURCE: Ward et al., 2011.

representatives of other government and nongovernmental agencies such as the Social Development Commission, Jamaica Social Investment Fund, Citizen Security and Justice Program, Community Security Initiative, Dispute Resolute Foundation, Peace Management Initiative, the Restorative Justice program of the Ministry of Justice, Violence Prevention Alliance, Peace and Love in Communities, among others. The several state agencies responsible for public services, such as electricity and water, should also be included in the interventions as needed.

Similarly, all parenting programs backed by a national policy on parenting should be coordinated with the YEO’s work. Budgetary and policy support is necessary for proven programs that can be scaled up to have an impact on the entire population.

Mentorship Program. This program focuses on unattached Jamaicans who fall in the 15-25-year age group and are from marginalized communities. Mentoring sessions will focus on (1) building quality relationships, (2) conflict resolution skills, (3) building leadership capabilities, (4) career or entrepreneurial exploration, and (5) promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Components of these programs are already in existence, but they have to be refocused and revitalised. The size of the gap to meet the needs of the

BOX 7-2

Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions

Greenwood and others (1996) compare interventions to reduce youth crime in the United States and find that providing high school students with incentives to graduate, which costs $14,000 per program participant, is the most cost-effective intervention, resulting in an estimated 256 serious crimes prevented per $US 1 million spent. Parent training prevents an estimated 157 serious crimes per $US 1 million, compared with 72 for delinquent supervision programs and 11 for home visits and day care. All of these interventions (excluding home visits) are more cost-effective that California’s “three strikes” law, which incarcerates for life those individuals convicted of three serious crimes (Rosenberg et al., 2006).

youth population and the cost of programs for national, parish, and community levels are outlined in Box 7-2.

Guiding the Way Forward

Moser and Spergel identified an increasing recognition that programs that focus on single issues have not been very successful in changing the lives of adolescents or reducing the overall levels of delinquency (Moser and van Bronkhorst, 1999; Spergel, 1995). These programs treat only the symptoms, not the underlying problems. Interventions need to be comprehensive and not run as vertical programs. Youth programs need to help adolescents out of high-risk environments and align them with positive mainstream activity. The programs must be guided by creative and effective planning delivered by highly respected and committed individuals with unrelenting dedication, based in the communities, who are truly and fiercely committed to this arduous, on-the-ground task.

Youth violence is a complex social phenomenon, but it is also a major development problem. In making the recommendations for developing interventions, it must be understand what works and what doesn’t work for youth violence prevention. Youth programs must be built on a firm foundation (parenting, life skills, literacy, and relevant education). These programs must be supported by the required budgetary allocation and, more importantly, the will to bridge the gap.

Conclusion

Young people represent a tremendous untapped potential in Jamaican society. Revamping youth development interventions to meet the challenges

of this group will provide a driving force for Jamaica toward sustainable development and economic prosperity. This will require the commitment of all segments of the society to focus on community prevention in order to effect the changes needed.

REFERENCES

Acker, C. J. 2010. How crack found a niche in the American ghetto: The historical epidemiology of drug-related harm. Biosocieties 5(1):70-88.

Aguilar, P., and G. Retamal. 1998. Rapid educational response in complex emergencies: A discussion document. Geneva, Switzerland: International Bureau of Education.

Apfel, R. J., and B. Simon. 1996. Psychosocial interventions for children of war: The value of model of resiliency. Medicine and Global Survival 3(A2).

Ashby, P. 2002. Child combatants: A soldier’s perspective. Lancet 360(9350):s11.

Bayer, C. P., F. Klasen, and H. Adam. 2007. Association of trauma and PTSD symptoms with openness to reconciliation and feelings of revenge among former Ugandan and Congolese child soldiers. Journal of the American Medical Association 298(5):555-559.

Beardslee, W. R. 1998. Prevention and the clinical encounter. American Journal of Orthopsy-chiatry 68(4):521-533.

Beardslee, W. R., and T. R. Gladstone. 2001. Prevention of childhood depression: Recent findings and future prospects. Biological Psychiatry 49(12):1101-1110.

Betancourt, T. S. 2010. A longitudinal study of psychosocial adjustment and community reintegration among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. International Psychiatry 7(3):60-62.

Betancourt, T. S. 2011. Attending to the mental health of war-affected children: The need for longitudinal and developmental research perspectives. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 50(4):323-325.

Betancourt, T. S., and K. T. Khan. 2008. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: Protective processes and pathways to resilience. International Review of Psychiatry 20(3):317-328.

Betancourt, T. S., and T. Williams. 2008. Building an evidence base on mental health interventions for children affected by armed conflict. Intervention: International Journal of Mental Health, Psychosocial Work and Counseling in Areas of Armed Conflict 6(1):39-56.

Betancourt, T. S., S. Simmons, I. Borisova, S. E. Brewer, U. Iweala, and M. de la Soudiere. 2008. High hopes, grim reality: Reintegration and the education of former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Comparative Education Review 52(4):565-587.

Betancourt, T. S., J. Agnew-Blais, S. E. Gilman, D. R. Williams, and B. H. Ellis. 2010a. Past horrors, present struggles: The role of stigma in the association between war experiences and psychosocial adjustment among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Social Science & Medicine 70(1):17-26.

Betancourt, T. S., I. I. Borisova, R. B. Brennan, T. P. Williams, T. H. Whitfield, M. de la Soudiere, J. Williamson, and S. E. Gilman. 2010b. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: A follow-up study of psychosocial adjustment and community reintegration. Child Development 81(4):1077-1095.

Betancourt, T. S., R. T. Brennan, J. Rubin-Smith, G. M. Fitzmaurice, and S. E. Gilman. 2010c. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: A longitudinal study of risk, protective factors, and mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 49(6):606-615.

Betancourt, T. S., I. Borisova, M. de la Soudière, and J. Williamson. 2011. Sierra Leone’s child soldiers: War exposures and mental health problems by gender. Journal of Adolescent Health 49(1):21-28.

Betancourt, T. S., S. E. Zaeh, A. Ettien, and L. N. Khan. In press. Psychosocial adjustment and mental health services in post-conflict Sierra Leone: Experiences of CAAFAG and war-affected youth, families and service providers. In New series on transitional justice, edited by S. Parmentier, J. Sarkin, and E. Weitekamp. Antwerp: Intersentia.

Bourgois, P. 1995. Workaday World, Crack Economy. Nation 261(19):706-711.

Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: The Harvard University Press.

Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers. 2008. Child soldiers: Global report 2008. London.

Crime in the Caribbean: In the shadow of the gallows. 2011. Economist, February 10.

Derluyn, I., E. Broekaert, G. Schuyten, and E. De Temmerman. 2004. Post-traumatic stress in former Ugandan child soldiers. Lancet 363(9412):861-863.

Donaldson, G. 1993. The ville: Cops and kids in urban America. New York: Ticknor & Fields.

Elbedour, S., R. Bensel, and D. T. Bastien. 1993. Ecological integrated model of children of war: Individual and social psychology. Child Abuse and Neglect 17(6):805-819.

Fox, K. 2003. Mapping unattached youth in Jamaica: Report prepared for IADB. Inter-American Development Bank.

Fox, K., and G. Gordon-Strachan. 2007. Jamaican youth risk and resiliency behaviour survey 2005: School-based survey on risk and resiliency behaviours of 10-15 year olds. Washington, DC: USAID.

Guha-Sapir, D., W. G. van Panhuis, O. Degomme, and V. Teran. 2005. Civil conflicts in four African countries: A five-year review of trends in nutrition and mortality. Epidemiologic Reviews 27(1):67-77.

Hawkins, J. D. 2007. Preventing youth violence in the US: Implications for developing countries. Washington, DC: PowerPoint presentation at Workshop on Violence Prevention in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Finding a Place on the Global Agenda.

HEART Trust-National Training Agency. 2009. Unattached youth in Jamaica. Planning and Project Development Division, HEART. Kingston, Jamaica.

Hobfoll, S. E., C. D. Spielberger, S. Breznitz, C. Figley, S. Folkman, B. Lepper-Green, D. Meichenbaum, N. A. Milgram, I. Sandler, I. Sarason, et al. 1991. War-related stress. Addressing the stress of war and other traumatic events. American Psychologist 46(8):848-855.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1994. Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Edited by P. J. Mrazek and R. J. Haggerty. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jacob, K. S., P. Sharan, Mirza, I. M. Garrido-Cumbrera, S. Seedat, J. J. Mari, V. Sreenivas, and S. Saxena. 2007. Mental health systems in countries: Where are we now? Lancet 370: 1061-1077.

Kohrt, B. A., M. J. Jordans, W. A. Tol, R. A. Speckman, S. M. Maharjan, C. M. Worthman, and I. H. Komproe. 2008. Comparison of mental health between former child soldiers and children never conscripted by armed groups in Nepal. Journal of the American Medical Association 300(6):691-702.

Lancet Global Mental Health Group, D. Chisholm, A. J. Flisher, C. Lund, V. Patel, S. Saxena, G. Thornicroft, and M. Tomlinson. 2007. Scale up services for mental disorders: A call for action. Lancet 370(9594):1241-1252.

Levy, H. 2001. They cry “respect”! Urban violence and poverty in Jamaica. Kingston, Jamaica: Centre for Population, Community and Social Change, Department of Sociology and Social Work, University of the West Indies, Mona.

Mazurana, D., and K. Carlson. 2006. The girl child and armed conflict: Recognizing and addressing grave violations of girls’ human rights. Florence, Italy: United Nations.

McGuire, J. 2008. A review of effective interventions for reducing aggression and violence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 363(1503): 2577-2597.

Medeiros, E. 2007. Integrating mental health into post-conflict rehabilitation. Journal of Health Psychology 12(3):498-504.

Ministry of Education. Jamaica education statistics 2009-2010 (derived data). Kingston, Jamaica.

Moser, C., and B. van Bronkhorst. 1999. Youth violence in Latin America and the Caribbean: Costs, causes, and interventions. LCR sustainable development working paper. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Multi-Country Demobilization and Reintregration Program (MDRP). 2009. MDRP partners meetings March 10-12.

National Family Planning Board. 2010. Fact sheet: Childhood and intimate partner violence in Jamaica.

O’Hare, B. A., and D. P. Southall. 2007. First do no harm: The impact of recent armed conflict on maternal and child health in sub-Saharan africa. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 100(12):564-570.

Otunnu, O. A. 2002. “Special comment” on children and security. Disarmament forum no. 3. Geneva: United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research.

Patel, V., R. Araya, S. Chatterjee, D. Chisholm, A. Cohen, M. De Silva, C. Hosman, H. McGuire, G. Rojas, and M. van Ommeren. 2007a. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 370(9591):991-1005.

Patel, V., A. J. Flisher, S. Hetrick, and P. McGorry. 2007b. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet 369:1302-1313.

Planning Institute of Jamaica. 2009. National Report of Jamaica on Millennium Development Goals. Geneva: for the UN Economic and Social Council Annual Ministerial Review.

Planning Institute of Jamaica. 2010. Economic and social survey Jamaica. Kingston, Jamaica: Planning Institute of Jamaica.

Prince, M., V. Patel, S. Saxena, M. Maj, J. Maselko, M. R. Phillips, and A. Rahman. 2007. No health without mental health. Lancet 370(9590):859-877.

Rosenberg, M. L., J. A. Mercy, V. Narasimham, and M. Marshall. 2006. Interpersonal violence. In Disease control priorities in developing countries. New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 755-770.

Samms-Vaughan, M. E., M. A. Jackson, and D. E. Ashley. 2005. Urban Jamaican children’s exposure to community violence. West Indian Medical Journal 54(1):14-21.

Saraceno, B., M. van Ommeren, R. Batniji, A. Cohen, O. Gureje, J. Mahoney, D. Sridhar, and C. Underhill. 2007. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 370(9593):1164-1174.

Saxena, S., G. Thornicroft, M. Knapp, and H. Whiteford. 2007. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 370(9590):878-889.

Scott, S. 1998. Aggressive behaviour in childhood. British Medical Journal 316(7126):202-206.

Simms, E.-M. 2008. Children’s lived spaces in the inner city: Historical and political aspects of the psychology of place. Humanistic Psychologist 36(1):72-89.

Southall, D. P., and B. O’Hare. 2002. Empty arms: The effect of the arms trade on mothers and children. British Medical Joournal 325(7378):1457-1461.

Spergel, I. A. 1995. The youth gang problem: A community approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ungar, M., M. Brown, L. Liebenberg, R. Othman, W. M. Kwong, M. Armstrong, and J. Gilgun. 2007. Unique pathways to resilience across cultures. Adolescence 42(166):287-310.

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). 2007a. Child protection from violence, exploitation and abuse: Children in conflict and emergencies. http://www.unicef.org/protection/index_armedconflict.html (accessed 2011).

UNICEF. 2007b. The Paris principles: Principles and guidelines on children associated with armed forces or armed conflict. Paris: UNICEF.

UNICEF. 2008. State of the world’s children 2008. New York: UNICEF.

UNICEF. 2009. Machel study 10-year strategic review: Children and conflict in a changing world. New York: UNICEF.

United Nations. 1989. United Nations convention on the rights of the child. New York: United Nations General Assembly.

Walker, S. P., S. M. Chang, M. Vera-Hernandez, and S. Grantham-McGregor. 2011. Early childhood stimulation benefits adult competence and reduces violent behavior. Pediatrics 127(5):849-857.

Wallace, D. 2011. Discriminatory mass de-housing and low-weight births: Scales of geography, time, and level. Journal of Urban Health 88(3):454-468.

Wallace, R., and M. T. Fullilove. 2008. Collective consciousness and its discontents: Institutional distributed cognition, racial policy, and public health in the United States. New York: Springer.

Wallace, R., M. T. Fullilove, and A. J. Flisher. 1996. AIDS, violence and behavioral coding: Information theory, risk behavior and dynamic process on core-group sociogeographic networks. Social Science & Medicine 43(3):339-352.

Ward, E., D. Hutchinson, H. Levy, and N. Figueroa. 2011. Youth Transition Model. Presented by E. Ward at Workshop on the social and economic costs of violence: The value of prevention. Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC. April 28.

Wessells, M. 2009a. Supporting the mental health and psychosocial well-being of former child soldiers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 48(6):587-590.

Wessells, M. 2009b. What are we learning about protecting children in the community? An inter-agency review of the evidence from humanitarian and development settings. New York: Save the Children.

Wilks, R., N. Younger, S. McFarlane, D. Francis, and J. Van Den Broeck. 2007. Jamaican youth risk and resiliency behaviour survey 2006: Community-based survey on risk and resiliency behaviours of 15-19 year olds. Chapel Hill, NC: Measure Evaluation.

Williamson, J., and L. Cripe. 2002. Assessment of DCOF-supported child demobilization and reintegration activities in Sierra Leone. U.S. Agency for International Development.

World Bank. 2011. World development report 2011: Conflict, security, and development. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, World Bank.

World Revolution. 2001. Child soldiers: A global problem. Global Report on Child Soldiers 2001. http://www.worldrevolution.org/Projects/Webguide/GuideArticle.asp?ID=9 (accessed 2011).