Building an Infrastructure to Support Clinical Trials

As noted in previous chapters, the existing clinical trials infra-structure1 is considered by many participants in Forum activities to be inadequate to meet the requirements of a transformed CTE that would promote the efficient development of new and effective treatments, develop valid and reliable evidence about the clinical effectiveness of health care treatments, undergird a learning health system, and gain the confidence and widespread engagement of the public, health care providers, and policy makers. The clinical trials infrastructure is currently developed on a trial-by-trial basis, or in a sponsor-specific manner, resulting in “one-off” trials that bring together substantial resources that are subsequently disbanded. In previous and ongoing Forum discussions, many participants in Forum activities have suggested that efforts to develop a consistent and reliable clinical trials infrastructure that lived beyond the single trial could increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the entire CTE.

Individual workshop participants described major infrastructure deficits and practical ideas for shoring it up and converting weaknesses into strengths. The discussion echoed a number of comments made in previous sessions and centered on current challenges and directions for solutions in the areas of data gathering and processing, investigator train

______________________

1 The clinical trials infrastructure refers to the necessary resources (human capital, financial support, patient participants, information systems, regulatory pathways, and institutional commitment) and the manner in which they are organized and brought together to conduct a clinical trial.

ing, patient and practitioner engagement, institutional resources, and the coordination and organization of clinical trial resources.

GAPS AND CHALLENGES IN THE CURRENT CLINICAL TRIALS INFRASTRUCTURE2

A key objective of health care reform in the United States is to encourage use of the most effective therapies and implementation strategies. This will require multiple types of clinical trials in many different settings.

—Paul Eisenberg, Amgen Inc.; Petra Kaufmann, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS); Ellen Sigal, Friends of Cancer Research; and Janet Woodcock, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, FDA

Clinical trials in the United States have become too expensive, difficult to enroll, inefficient to implement, and ineffective to support the development of new medical products, or the clinical effectiveness of these products, under modern scientific standards of evidence. This critique is expressed in the Discussion Paper prepared by Paul Eisenberg, Amgen Inc.; Petra Kaufmann, Director, Office of Clinical Research, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), NIH; Ellen Sigal, Chair and Founder, Friends of Cancer Research; and Janet Woodcock, Director, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, FDA. (See “Developing a Clinical Trials Infrastructure” in Appendix G). Ultimately, the purpose of CTE transformation is to facilitate development of more efficient and effective drugs and treatments, partly through continuous improvement of health care. A broad-based, sustainable infrastructure could support multiple types of clinical trials in different settings. Box 5-1 shows some of the elements of the clinical trials infrastructure that could be transformed.

A leading shortcoming of today’s CTE is low participation rates by patients and the public. To increase participation, the paper suggests the creation of clinical trial networks that are one of the following: disease-specific; created through CTSAs for a constellation of diseases or oriented around a specific subpopulation (e.g., children); or a “hub-and-spoke” arrangement between AHSSs and community health care providers. The success of CF advocates illustrates the power of a network to initiate and

______________________

2 This section is based on the presentations and Discussion Paper by Paul Eisenberg, Senior Vice President, Global Regulatory Affairs and Safety, Amgen Inc.; Petra Kaufmann, Director, Office of Clinical Research, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), NIH; Ellen Sigal, Chair and Founder, Friends of Cancer Research (unable to attend workshop); and Janet Woodcock, Director, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, FDA. (See Appendix G for the Discussion Paper “Developing a Clinical Trials Infrastructure.”)

BOX 5-1a

Elements of the Clinical Trials Infrastructure Discussed at the Workshop

• Investigator recruitment

• Regulatory approval to conduct a clinical trial (e.g., IND in the United States)

• Contractual agreements between sponsors, institutions, and investigators

• Participant recruitment plan

• Coordination of global investigators and research sites

• Quality control systems

• Data collection, management, and analysis

• Data standards

• Communication of results

• Registration of trials and results with ClinicalTrials.gov

_____________________

a This box is based on the Discussion Paper by Paul Eisenberg, Senior Vice President, Global Regulatory Affairs and Safety, Amgen Inc.; Petra Kaufmann, Director, Office of Clinical Research, NINDS, NIH; Ellen Sigal, Chair and Founder, Friends of Cancer Research (unable to attend workshop); and Janet Woodcock, Director, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, FDA. (See Appendix G for the Discussion Paper “Developing a Clinical Trials Infrastructure.”)

implement clinical trials, as this advocacy community has been highly influential in promoting extensive research on the disease. Several organizations in the United States and United Kingdom jointly funded a recently reported study (Ramsey et al., 2011). Woodcock pointed to this study as an example of how a network of organizations can collaborate to sponsor studies that contribute to medical knowledge. In the study, at least five organizations—a pharmaceutical manufacturer, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutic Development Center, NIH, and two British entities—funded a multisite RCT of a drug that increases the effectiveness of the CF transmembrane conductance regulator protein; the study found substantial improvements in weeks 2 through 48 (Ramsey et al., 2011). This type of effort, Woodcock noted, integrates research and clinical care and leads to continuous quality improvement through rigorous evaluation of interventions.3

______________________

3 Since the workshop, FDA approved a new therapy, Kalydeco, in January 2012 to treat CF patients with a specific genetic mutation (approximately 4 percent of CF patients, or 1,200 individuals, have the mutation targeted by this new drug). The new drug is the first personalized treatment that targets a specific abnormal protein product of a specific gene in a subset of CF patients. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation partnered with drug developer Vertex Pharmaceuticals to develop and study the drug in the relevant CF patient population. The partnership that led to the approval of this new therapy could provide a model for future drug development and patient group collaborations. For more information visit http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm289633.htm (accessed March 28, 2012) and http://blogs.fda.gov/fdavoice/index.php/2012/01/how-science-and-strategic-collaboration-led-to-a-new-personalized-cystic-fibrosis-treatment-for-some-patients/ (accessed March 28, 2012).

Robert Califf, Duke University Medical Center, noted that, as research networks grow and expand, it will be important to prevent them from becoming ossified or complicating opportunities to collaborate with external researchers.

Web-based innovations also could meet other infrastructure gaps. A participant noted that the infrastructure of the future could consist of web-based trials now being piloted, with a single “virtual” investigator and trial participants nationwide.

Some relief from the need to comply with many different requirements of multiple federal agencies has come from the Common Rule, or Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, originally adopted in 1991 and amended in 2005.4 This regulation, with extensive new updates now under consideration, in effect harmonizes the approaches of some 17 federal agencies on IRB-related matters (HHS, 2011). Issues currently under consideration in review of the Common Rule include mandating a central IRB for multisite domestic studies; informed consent for future use of bio-specimens for research purposes (along with harmonization of Common Rule and HIPAA requirements on this subject); and requiring that even relatively small organizations provide extensive data security safeguards (CenterWatch, 2011; HHS, 2011). Additional relief from regulatory challenges could come through the auspices of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, a forum for the industry and regulatory authorities in the United States, Europe, and Japan to rationalize international regulations.

ESTABLISHING AN INFRASTRUCTURE TO SUPPORT A TRANSFORMED CLINICAL TRIALS ENTERPRISE

I am concerned that the message is coming through that clinical trials are all good, more clinical trials are better, and we need to make it easier to do more …. [G]ood clinical trials are good, bad clinical trials are not good.

—Deborah Zarin, ClinicalTrials.gov, National Library of Medicine

______________________

4 The Common Rule is based on HHS’ basic regulation on Protection of Human Subjects (45 CFR 46, subpart A). Amendments were proposed in 76 (143) Federal Register (FR) 44512-44531 (July 26, 2011), comment period extended 76 (170) FR 54408 (September 1, 2011).

Responding to the Discussion Paper were Louis Fiore, Director, VA Cooperative Studies Program Coordinating Center, VA Boston Healthcare System; Michael King Jolly, Senior Vice President, Quintiles Drug Development Innovation; and Karen Margolis, Director of Clinical Research, HealthPartners Research Foundation, during a panel session moderated by Clyde Yancy, Northwestern University. Yancy noted that clinical practice guidelines—and even approvals of medical devices or other modalities— often lack a firm evidence base. Some panels responsible for clinical practice guidelines rely on data from other countries with a different population mix or clinical approach, data from a limited population (such as men only), or the results of trials for which the clinical end points were not developed in conjunction with patients. In short, too often there is no rational business model for developing evidence to support clinical guidelines, utilizing the dedicated services of a stable cadre of researchers within a single institution. Fiore, Jolly, and Margolis described the evolving and promising research capacity, built around large patient populations, of the VA, PACeR, and HMO (health maintenance organization) Research Network (HMORN), respectively. Disruptive ideas include

• a patient-centric approach, as opposed to the current approach that includes a selection bias in recruiting patients for a trial, as participants often are recruited only when they present to a particular provider;

• a hospital approach, with new strategies, similar to reduced payment for avoidable readmissions, which have served as a powerful incentive for change; and

• incentives and centralized training for investigators, combined with an end to the stigma associated with conducting industry-sponsored research.

Clinical Research Infrastructure at the VA5

Fiore discussed clinical research in the VA. More than 100 VA centers are approved for research, and staff is allocated time for the effort to conduct it. Every VA hospital has a research office and a nonprofit subsidiary to handle financial transactions. Because VA hospitals, and not a separate academic institution, are the grantees, the VA hospitals can collect indirect costs under the grants, thus providing greater incentives and support for research within the VA. The extensive VA research infrastructure includes the Office of Research and Development with, among other features, a

______________________

5 This section is based on the presentation by Louis Fiore, Director, VA Cooperative Studies Program Coordinating Center, VA Boston Healthcare System.

centralized IRB; monitoring, pharmacy, and training facilities; and the ability to conduct small observational pilot studies to assist the development of larger research projects. The Genomic Informatics System for Integrative Science (GenISIS), perhaps the VA research “crown jewel,” is an IT environment that uses both phenotypic and biologic data to facilitate the recruitment, enrollment, and analysis of people in clinical trials, especially studies involving genomic medicine. GenISIS provides numerous applications and databases, performance computing and data storage, and links to external data sources as well as patient records. Other VA advantages in conducting research include a large and stable patient population; a model EHR system, coupled with secondary use of data to identify patients meeting particular research criteria; and a secure clinical data warehouse (VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure, or VINCI). Emerging VA programs include point-of-care research (using EHRs for randomization and workflow analysis) and development of the Million Veterans Program genomic research preconsented population, which will include banked biologic specimens as well as other resources. Also under development is the use of EHRs to identify patients who meet criteria for individual studies; this outreach activity will complement the patient portal where veterans can learn about, and enroll in, studies. Finally, expanding VA research resources to include DoD personnel will make the system even more powerful.

Partnership to Advance Clinical Electronic Research6

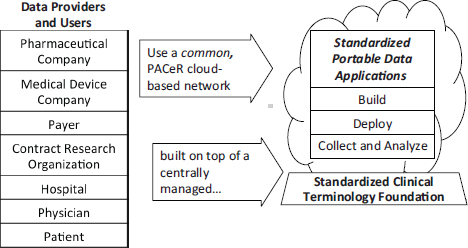

Jolly described PACeR, a consortium of 13 hospitals in New York State and many other inpatient and ambulatory care providers (see also Chapter 2) using an open-source platform for research. Established in 2010, PACeR is a public–private partnership intended to develop economically sustainable businesses to support translational medical research across the nation. Figure 5-1 depicts PACeR’s capacity to standardize clinical research and complete clinical databases.

PACeR is both an operating system and a series of applications, using cloud computing technologies. Oracle is a partner and is involved in building greater interoperability into the system. Consistent with Fiore’s comments regarding the VA, infrastructure capacity is key to PACeR, and standards— affecting policies, practice guidelines, procedures, methods, technologies, and data—are the key to interoperability. With respect to data, common standards dictionaries are used, so data from institutions with different data systems, or different versions of the same system, can be matched.

______________________

6 This section is based on the presentation by Michael King Jolly, Senior Vice President, Quintiles Drug Development Innovation.

FIGURE 5-1 The PACeR (Partnership to Advance Clinical electronic Research) system fills the EMR clinical data gaps and captures uniform data across all clinical data capture sites, which is needed for evidence-based research.

SOURCE: Jolly, 2011. Presentation at IOM workshop on Envisioning a Transformed Clinical Trials Enterprise in the United States: Establishing an Agenda for 2020.

PACeR brings providers of information and buyers of information into a common space. It can generate new information through queries, and each institution can access the full array of data. In addition, PACeR provides patients with a portal, called MediGuard, for learning about studies for which they may meet eligibility criteria.

HMO Research Network7

Margolis described HMORN, a consortium of 19 large integrated health service providers serving people of all ages and other characteristics in all major regions of the country. Because HMORN includes several disease networks—on vaccine safety, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, mental health, and other areas—it is, in a sense, a network of networks, able to facilitate longitudinal studies. It functions as a virtual data warehouse, with data residing at each site but accessible to all members and thus capable of being consolidated. Each site has staff with sub

______________________

7 This section is based on the presentation by Karen Margolis, Director of Clinical Research, HealthPartners Research Foundation.

stantial programming and informatics expertise. Data are derived from tumor registries, mortality records, pharmacy orders, and, under development, even dental records. Costs of care can be calculated easily. To date, HMORN activity has concentrated on observational studies, but clinical studies and pragmatic trials are anticipated. Facilities include a voluntary central IRB and streamlined contracting. In addition, HMOs serve as a natural vehicle for contacting practitioners and for disseminating and using research findings.

During the discussion following panelist presentations, Marissa Miller, NHLBI, NIH, noted the success of the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS), a national registry for patients who are receiving mechanical circulatory support device therapy to treat advanced heart failure. Miller highlighted that the NHLBI-funded registry was created with buy-in from stakeholders across the clinical research enterprise—CMS, FDA, academia, industry, scientists, and clinicians—who together developed rigorous data definitions, extensive data collection, and auditing processes for the registry. Use of the patient data in this robust registry has resulted in multiple research publications advancing medical evidence and guiding improvements in technology as devices to treat advanced heart failure evolve. Recently, the registry data has also been used in conducting clinical trials. INTERMACS serves a dual function: it (1) develops common definitions and a reporting system for adverse events and (2) generates a reference population for clinical trials, effectively streamlining the startup of clinical trials by removing the necessity to recruit a control population.

Table 5-1 provides an integrated summary of some the infrastructure challenges and possible directions for transformation cited in the Discussion Paper and presentations by Eisenberg, Kaufmann, and Woodcock and noted by individual workshop participants and audience members.

| Challenge | Possible Course of Action |

| Insufficient evidence to support real-world clinical practice |

• Multiple trials, in various settings, to generate more complete results that are relevant to clinical practice; • Increased input from practitioners and patients into development of trials; • Post clinical questions online; • IHSs’ creation of a disease problem list to guide improvements in identifying study topics and designing trials or choosing the appropriate research method to answer the question being posed; and • Greater involvement of payers, employers, health system CEOs, and others in developing research tools and clinical trials to produce more relevant findings (e.g., building from the success of INTERMACS discussed above). |

| Insufficient engagement and participation in clinical trials by community health care providers and the public |

• Design clinical trials that are appropriate and attractive from a patient’s perspective—consider outcomes meaningful to the patient population and society; • Recruit participants through online networks; • Provide patients with standardized information on clinical trials, and develop a participation card similar to organ donation cards; • Web-based clinical trials that facilitate participation nationwide; • Alert clinicians when a patient meets criteria for participation in a trial, using EHRs and clinical trial identifiers; and • Increased encouragement and advocacy of participation in research by professional medical societies. |

| Lack of coordination— trials are conducted in a one-off manner |

• Online trial infrastructure created through public-private partnerships; • Greater use of research coordinators; • Implement national research labs (similar to those supported by the Department of Energy) with core budgeting and a more engineered system of health learning; • Standardized online training programs and credentialing of investigators; and • Access to investigator track records (e.g., success recruiting patients to participate in clinical trials to date, ability to submit timely clinical trial data to coordinating centers) by research centers conducting clinical trials. |

| Challenge | Possible Course of Action |

| Poor communication about trials |

• Develop opportunities for meaningful communication among patients, researchers, and community physicians about clinical trials; • Provide more information online about trials, perhaps through a user-friendly interface to ClinicalTrials.gov; • Transparent and reliable communication of trial results to the public through a patient portal; and • Facilitate remote clinical trial participation through mobile and web-based technologies so that patients do not need to visit research centers or physician offices for recording of progress. |

| Regulatory and administrative barriers |

• Standardized contracts to reduce trial start-up delays; • Online protocol tools and common technical documents for applications to conduct trials; • Harmonize international requirements for reporting adverse events; • Creation of a universal numerical scheme to identify clinical trials across the world; • Build the U.S. regulatory framework for co-development of new drugs and the devices to administer them; • Harmonize clinical research site inspections; • Centralized IRBs, and other forms of relief under HHS Common Rule (see text below); and • More flexible FDA and NIH processes for determining type of trial appropriate for a drug investigation phase or research question. |

| Financial Disincentives |

• Locally adjusted fee schedules for clinical research tasks, to compensate practitioners; • Private payer support, modeled on Medicare program, to provide “coverage with evidence development” (CED) for novel treatments; and • Funding support for clinical trials by employers concerned about health care–related costs. |

SOURCE: This table is based on comments made by individuals participating in workshop discussions and the presentation of the Discussion Paper: Eisenberg et al, 2012. Developing a Clinical Trials Infrastructure. Discussion Paper, Institute of Medicine. (See Appendix G.)