Overview of the Department of Homeland Security Resilience Issues and Programs

This chapter includes materials presented at both the September and November 2011 workshops. Although some of the issues discussed are specific to the needs of particular groups such as law enforcement or operations center personnel, many of the presentations are relevant to all the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) employees.

At the September workshop, Kathryn Brinsfield and Alisa Green collaborated to present an overview of resilience concerns within the operational and law enforcement components as well as a review of the current DHS resilience initiatives. Brinsfield is the acting deputy chief medical officer and the director of the Workforce Health and Medical Support Division within DHS’s Office of Health Affairs. Green is a human resources specialist, employee assistance program (EAP), and WorkLife Program Manager within the Policy and Programs Division of the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer (OCHCO).

Three presentations from the November workshop are also included in this chapter. Vicki Brooks, Deputy Chief Human Capital Officer (CHCO), presented information on DHS’s human capital infrastructure. The Office of Operations Coordination and Planning chief of staff Mary U. Kruger discussed stressors faced by operations center personnel as well as how they relate to high-level security clearances. Kimberly Lew, chief of DHS’s Personnel Security Division in the Office of the Chief Security Officer, presented an overview of the security clearance process. Brooks, Kruger, and Lew also participated in a panel discussion on employee perceptions and disincentives for seeking assistance that may negatively affect resilience.

At the end of each session, speakers responded to questions from the workshop participants including planning committee members, sponsor

representatives, speakers and panelists from other sessions, and attendees. Box 2-1 includes a summary of the stressors and potential challenges the speakers from DHS identified through their presentations. Additional information about resilience concerns and programs within individual DHS component agencies can be found in Chapter 8.

BOX 2-1

DHS-Identified Employee Stressors

- Repeated exposure to traumatic critical incidents

- Fatigue from shift work or chronically long hours

- Nature of the mission

- Frequent job relocation and deployment

- Balance between professional and personal obligations

- Real and perceived consequences of seeking assistance such as stigma, lose of clearance, impact on promotion possibilities

DHS-Perceived Challenges in Developing Resilience Programs

- Large, decentralized organization with diverse cultures

- Privacy laws and regulations that may restrict outreach to families

- Funding and prioritization of resources

- Stigma associated with seeking assistance

- Decentralization of human resource infrastructure and operations

AN OVERVIEW OF DHS RESILIENCE PROGRAMS

In late 2009, Deputy Secretary Lute tasked the DHS Office of Health Affairs to develop a department-wide wellness and resilience initiative. DHSTogether was started, Brinsfield stated, with two central objectives: prevention of employee suicides, particularly in the law enforcement organizations, and improvement of morale and engagement as measured by the “Best Places to Work in the Federal Government” rankings.1

____________

1The “Best Places to Work in the Federal Government” is an index derived from the annual government-wide Employee Viewpoint Survey (EVS).

Employee Viewpoint Survey

The federal government has an annual all-employee survey called the Employee Viewpoint Survey (EVS). The survey tracks engagement and morale, and includes a wide range of questions such as questions about employees’ feelings about management, the organization, their ability to get their work done, and their intention to stay within the organization. Every year a sub-index of the survey is analyzed by the Partnership for Public Service into the ranking of the best places to work in the federal government. Agencies are ranked by size—large, medium, and small. This ranking system is focused on employee well-being, resilience, and work life and is therefore important to the department. Green noted that DHS is currently ranked 28th out of the 33 agencies rated. In the past, DHS has consistently scored at the bottom of the rankings. The deputy secretary also tasked the Office of Health Affairs (OHA) with moving DHS to the top 10 of the rankings.

At this point, the EVS ranking is the most consistent baseline data available on employee satisfaction. Given the size and complexity of the department it is difficult to determine to what degree it reflects the attitudes of the components. The media exposure reinforces the public perceptions about the department.

DHS faces several challenges in trying to tackle this issue. The size of the organization and the diversity of components, their missions, and their individual organizational cultures make a rigorous needs-assessment complicated. Additionally, a comprehensive needs assessment is expensive, and resources are limited.

It is possible to get some information from existing systems such as EAP utilization rates. However, there is no assessment of the effectiveness of the programs or any potential outcomes related to them. As a result, it is not currently possible to evaluate the progress of existing programs such as the impact of EAPs and peer-support programs.

Planning committee chair James Peake asked if DHS was able to stratify the EVS results by component to see if there is variance across the organization, and if so where. Green responded that EVS results are provided at three levels. For instance, there is an EVS score for DHS overall, for DHS headquarters, and for the OHA. Components would receive the DHS overall score, the component score, and then one more breakdown to the level below the component. It is not possible to get EVS data on a particular point of entry or location. The EVS response

rates are generally around 50 percent, which is typical for this type of survey. The response rate also tends to vary from year to year.

Brinsfield noted that although there is often variation on some issues within the results, in general none of the components scores are very high. On the positive side, survey respondents from almost all the DHS components identified the mission as the most important aspect of their job and why they stay. On the negative side, the component employees reported they do not feel empowered on the job and are frustrated by work-life issues. Peake commented that the data provide some support for the idea that this is a systematic issue and not the result of a small group of outliers.

Exploring Best Practices

Planning committee member David Sundwall asked if DHS had explored the best practices of high-ranking agencies to see if they could be adopted by DHS. Brinsfield replied that her group visited all the high-ranking agencies. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) ranks high every year. The NRC has applied some workforce initiatives that have been very successful. The problem is that the NRC is very different from DHS. It is a relatively small and cohesive agency where all the staff are located in one place. One NRC program is a values initiative that looks at whether organizational values and behavior align. That type of initiative would not be culturally relevant to law enforcement agencies.

The DHSTogether initiative also looked outside the government for guidance. Unfortunately, many of the private industry best practices do not translate to government in general or to DHS specifically. For example, DHS is not allowed to give employees free coffee, happy hours, or even parking spaces.

DHSTogether

The DHSTogether program has evolved over the past 2 years. The initial plan was ambitious and included a task force charged with making policy recommendations, as well as the assistant secretary reporting progress to the senior leadership at monthly meetings. The task force members were very dedicated, and their work was invaluable, interesting, and useful. From the beginning the initiative has been collaborative and includes people from various components within DHS. Many of the contributors attended the workshops, and Brinsfield commented that their

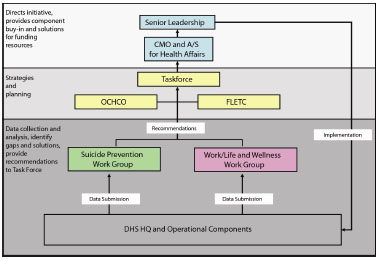

support is one of the strengths of the program. However, it became clear that without the ability to establish policies at a high level, it was not an effective use of the participants’ time. As a result, the group was reorganized in the second year. The task force started looking at other ways to continue to work together and participate. Figure 2-1 illustrates the current structure of DHSTogether.

The current DHS Employee and Organizational Resilience program is based on four pillars: leadership priority; training; policies, procedures, and programs; and communication.

FIGURE 2-1 DHSTogether operations structure.

SOURCE: Brinsfield and Green, 2011.

NOTE: A/S, Assistant Secretary; CMO, Chief Medical Officer; DHS HQ, Department of Homeland Security Headquarters; FLETC, Federal Law Enforcement Training Center; OCHCO, Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer.

Leadership

After looking at several models of employee and organizational resilience interventions, it was clear that leadership had to be a priority. Based upon the work in the military, leadership needs to be fully

engaged, on board, and present in the discussions. Interest by the leadership was initially very high both at the component and at the front-office level. Over time, the actual day-to-day knowledge or involvement has diminished as other important issues have taken priority.

Training

While developing the initial training sessions, the program borrowed heavily from Army and Navy resilience models. The first stage of the training included the following elements:

- Physical state: Physical activity, nutrition, healthy choices, general health

- Emotional state: Stress management, healthy relationships at work and home, mental health, spirituality

- Family/community: Healthy relationships with family and friends, connections to community, interests outside of work

- Work: Engagement, productivity, control and empowerment, career development, effective management

- Culture: Diversity, supportive work environment, organizational values, leadership

- Environment: Work location, work conditions, climate, outside influencers

Policies, Procedures, and Programs

As is common in the federal government, the development and implementation of new policies is complicated and requires multiple layers of clearance before program designs can be put in place. As an example, Brinsfield noted the research indicates that the inclusion of family is an important part of resilience programs. However, there are limitations to the program outreach efforts. Unlike in the military, employers are not allowed to ask if an employee has a family. Employers have to be careful about outreach and contacting the family because of privacy laws that unintentionally make it difficult to get information about support to families. These types of policy obstacles are an ongoing element of the program development.

Communications

Brinsfield stated that within DHS there is a huge cultural divide between various groups. Although it might be possible to break the groups down further, Brinsfield noted that in general, it is important to recognize there are two very different and separate communities within DHS—law enforcement and policy personnel. As a result, culturally appropriate communication is critical. DHS has decided to pursue a “one community, one message, different strategies” communications approach with the overarching message of “We take care of our employees so they can achieve the mission.” Under this primary message are also efforts to target training and program delivery to the varied subcultures within the department.

Program Progress

In the first year of the program, the task force and working groups were formed. At the direct request of the deputy secretary, the department also had a rolling stand-down to focus on resilience training and awareness. A stand-down is a temporary cessation of normal operations. The stand-down lasted about a month and was the first of its kind for DHS. Never before had multiple levels of DHS had a single training on an acute issue like this.

At the end of the first year, the program turned its attention to becoming more effective in supporting the different components. It was decided that symposiums would be the best approach. The resilience symposiums brought together speakers from a broad spectrum of backgrounds including human capital, health services, the DHS EAP, contracting officers’ technical representatives, and peer-support elements. The meetings had an open format to allow presentations of new materials and to encourage discussion. There have been two symposia to date. Fifty people from the components, headquarters, and peer-support staff attended the first symposium, and 62 people attended the second.

Brinsfield commented that 92 percent of DHS employees participated in the first training with positive feedback in 70 percent of the participants. The initial responses and the increasing information OHA has gathered from the focus groups were positive and productive. Brinsfield added that with a concerted effort and resources the program could become more effective.

Information Sources

DHS Agency-Wide Program Inventory

The task force inventoried all the existing programs supporting resilience efforts at the component agencies. The inventory showed there were some aspects of resilience programs already in place throughout the department, but it also indicated that there was very little consistency among programs. Additionally, the inventory did not identify uniform gaps making it difficult to determine what the next steps ought to be, given the limited resources. The primary lesson from the inventory was that further research is needed to determine best options for maximizing current programs and services.

Within DOD standards, guidance documents, and deployment policies are engrained and intrinsic to the organization and how it functions. DHS is just starting to put all of these policies in place. For instance, within DHS there are about 200 separate occupational health contracts, and embedded in those contracts are many of the EAP contracts. The diversity of contracts creates logistic issues. For example, during the vaccinations for H1N1, DHS employees that needed to be vaccinated could not go to a clinic in the DHS office across the street because it was under a separate service contract.

The inventory found that although all employees have access to an EAP, the marketing, accessibility, and quality of those programs varied widely. Almost all of the components have some type of peer-support program. For the most part, those programs are not funded annually, nor do they have resources specifically set aside for support.

The diversity in program design has resulted in low EAP utilization rates. Additionally, the programs were not always well positioned to meet the needs of the staff because of varied levels of program maturity and availability. For instance, after an acute incident, the EAP was asked to provide support for the unit. The EAP responded that its contract allowed for a 3-day turnaround so its staff would be available after 3 days. Another contracting concern is that most contracts do not specify that EAP providers must be familiar with the populations and their cultures. In the case of law enforcement officers, it is important that EAP providers, whether they be counselors or peer-support facilitators, must understand the background of their clients. Another example of the variability of services is health screenings. Some components only had a health

screening at the point of hire while others had a health screening every 2 years. Similar issues were seen with access to occupational health clinics.

After the first DHSTogether training session, representatives from the components contacted OCHCO and indicated that EAP utilization numbers were going up. From the perspective of the resilience initiative this was seen as a positive sign.

In terms of flexible schedules and telework arrangements, participation in these types of arrangements is driven by the type and demands of the position, and not everyone should have this option. With that said, the ability to have flexible schedules and do telework is highly variable. Access to on-site fitness facilities was also extremely variable.

Human Resource Audits

Every 3 years, OCHCO performs an audit of the components’ human resource systems. It is a very broad activity that looks at the logistic and process aspects of human resources to determine if they are compliant with various standards. In the past year, members of OCHCO’s WorkLife team have started to accompany the auditors to hold employee focus groups. To date two components have participated in this activity. The discussions largely focus on the EAP and work-life issues and have been extremely enlightening. As a part of the audit, however, the focus groups only take place every 3 years.

Other Information Sources

All of the resilience initiative activities, such as the stand-down and symposiums, provide time for comments from participants. The feedback from these events is used to inform the ongoing work of the resilience initiative.

Although the resilience initiative is separate from the work being done in OCHCO, it is hoped that, depending on funding, the resilience program will continue to go out to the components over the next several months. Green added that sessions with employees from Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) field offices were scheduled for the end of September 2011. The idea is that information from these discussions will provide insight into the results of the EVS. The sessions last only about 60-90 minutes, but they will provide opportunities to meet with the employees directly to discuss resilience and work-life concerns. Additional sessions with the

Federal Air Marshal Service, the Transportation Security Administration, and other components are also being planned.

Focus group participants may have issues such as stigma, barriers to access, and inhibitions about discussing personal issues in front of coworkers, noted planning committee member Scott Mugno. Mugno questioned the quality of the information resulting from the focus groups. To address these concerns, Green noted that the focus groups were designed with open-ended questions, which allow participants to take the discussion where they want. Notes are not taken until after introductions, and no comments are attributed to individuals. No one wears a suit, and chairs are set up so no one sits behind anyone else. Brinsfield commented that participants appeared more inclined to talk openly because the facilitators were from headquarters and distant from the components. Participants were more comfortable talking with someone outside their own organization.

Green noted that based upon some of the feedback from the training sessions, her primary concern was survey fatigue. Training participants have commented that it was hard to see the value of the survey when they had answered these questions before and no changes resulted.

Workshop speaker Fran Norris noted that the focus of the current program planning is on immediate operational concerns. She wanted to know if the program was engaged with partners such as university programs and various centers of excellence that DHS currently funds to do research relevant to terrorism and terrorism response. Brinsfield responded that the OHA has attempted to pursue this option but has found that the research is generally fairly specific to certain issues. The symposia were intended to connect with different people with different types of expertise to find different ways of looking at the issues. She also noted in order to make the research possible, researchers must build trust within the first-responder culture, which is a difficult task.

Work-Life Index

OCHCO is developing an index that is intended to quantify work-life issues. The index will pull information together into one place to be used as a means to increase component awareness and accountability for these issues. However, the usefulness of the index is dependent upon a component’s willingness to use it as an accountability tool. Although OCHCO can lead the effort, components have to take the commitment seriously to make the changes.

The index attempts to boil down multiple complex issues into a useable information tool. It is important that it not be made so simple that it no longer provides actionable information. The index includes information from three sources—the EVS, a checklist of program/service availability, and results of an exit interview survey.

The information from the sub-index of the EVS results focusing on work-life and resilience issues accounts for 70 percent of the index. Twenty percent of the index is based on a simple checklist indicating whether the component offers certain policies and programs. It is important to note that at this point the index does not include information about the quality or utilization of these programs. Currently the checklist only indicates if the program is available at the component’s headquarters and may not represent what is available to the hundreds of field offices.

The remaining 10 percent of the index is based upon DHS performing an agency-wide exit survey. The response rate is very low at this point because it is new, but response rates will increase as the effort matures. This survey includes specific questions around work life and engagement issues pulled out as a sub-index. Green noted that there were some initial concerns that the exit survey data would not accurately reflect people’s concerns because people would be hesitant to say something negative because it might impact future career plans or burn bridges. However, the initial data indicate that comments are heavily weighted toward concerns with work-life balance.

As more information becomes available and the index matures, adjustments can be made to improve its usefulness. The intention is that components will engage with the process. Green commented that components can collaborate on identifying issues to address and see what impact efforts have on the index results over time.

There are several components within DHS where employees and their families move every 2 to 4 years. Although these groups have similar issues with relocation as military families, DHS does not have the support systems and infrastructure to address this issue.

Staff Turnover

Sundwall asked if attrition data are used in the index. Green noted that at this point the index does not include attrition. Brinsfield added that some of the components still have remarkably high attrition, which is consistent over time. Summary panelist Kevin Livingston commented that in the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center the majority of

people who leave do not actually leave the government but transfer into different agencies.

Disgruntled employees have a huge effect on the moral and productivity of a unit. Sundwall added that one of the problems he faced while running a federal agency was the inability to fire unproductive or difficult personnel. Brinsfield noted that often that is a management issue. The resilience program’s role is as a health support function and should not get involved directly in management issues. Green also noted that the EVS results in most federal agencies consistently show that employees complain about management not dealing with poor performers. This is true in DHS as well. OCHCO is working to standardize the performance management system including the tools that managers need to address concerns with poor performers.

Leadership and Management Training

Planning committee member Karen Sexton asked what percentage of DHS has a management role, and if the department has mandatory training for managers and leaders. She noted that in her experience in nursing, management problems are one of the main reasons people choose to leave jobs. Green responded that some of the components have had leadership training programs in place for a long time and others have not. Within the past year, a leader development program started out of the Chief Human Capital Office. Brinsfield noted that it is difficult to estimate the number of managers from the top down to the first-line managers at the GS-12 and GS-13 levels.

The CBP recently began training for all its managers, and other components are starting to as well. Many of the first-line leaders and managers are stressed; they are trying to do their best in a complex organization that is often understaffed and underfunded, and they often do not feel adequately supported in their job. Brinsfield added that she has heard many times at all levels of the workforce that employees are feeling the same stressors.

Livingston pointed out that management training is not the same as leadership training. Management training is about process, procedures, and forms. There is little training on how to be a good leader, which he felt was an area that needs improvement.

Family Outreach and Engagement

Mugno asked if DHS had thought through ways to reach out to families. Brinsfield indicated that to her knowledge the OHA has been told that privacy laws prevent them from conducting outreach to families. Planning committee chair James Peake noted that it would be worth giving the issue a more in-depth look to determine if there are specific legal prohibitions or if there are other means to reach out to the families and include them in resilience programs. Logistic concerns and barriers to family outreach are also discussed in Vicki Brooks’ Department of Homeland Security’s Human Capital Framework presentation below.

A workshop participant asked if family resilience in emergencies and dealing with daily life stressors affect organizational resilience and community resilience. Fran Norris, a speaker from the session looking at definitional issues, noted that several people are doing research in family and community resilience. However, it is very difficult to examine resilience at multiple levels—individual, family, organization, community, society—simultaneously. Family resilience is critical in helping organizations such as DHS to not only respond to disasters but also be more resilient in general.

Identifying Stressors

Human resource surveys such as the EVS generally reflect people’s dissatisfaction with what is currently going on, noted summary panelist Joseph Hurrell. Although this can be a surrogate measure of job strengths, it does not actually target the kind of specific conditions that drive the EVS results. It is possible to develop the most effective work-life balance program in the world and have it still not be reflected in the EVS. It is important to address the types of conditions that are related to that job dissatisfaction. Does DHS have the ability to conduct a department-wide survey beyond the traditional human resource survey that specifically seeks to identify the job stressors? The logic being that if the stressors are identified, an agency would be better able to develop an effective intervention. Both Green and Brinsfield expressed several concerns about being able to implement a department-wide survey, including the level of resources needed to field a large-scale survey, Office of Management and Budget (OMB) approval time, and survey fatigue.

Long-Term Versus Incident-Specific Resilience

Brinsfield indicated the OHA is primarily interested in long-term resilience. As a result, it is not focused on a single event. Instead her office is looking at the 20-year cumulative effect of multiple pre-events, events, and post-events. Peake noted that workshop speaker Robert Ursano found that although only a subset of people experience an acute critical incident, the entire deployed population experiences stress. Everybody is stressed in that type of environment.

Green noted that many groups voiced concerns about controlling or managing the operation pace. For instance, when employees are told that something is urgent, they want to know that it really is urgent. On border patrol, if supervisors indicate there is an emergency, there probably is one. However, is it an emergency when an employee is told at 5:00 p.m. that the policy drafted 6 months ago suddenly is urgent and must be modified and submitted to leadership by 9:00 a.m. the next morning? It is understandable that in some cases, such a scenario is actually an emergency, but when the work pace is consistently high, it becomes hard to manage.

Traumatic Incident Management Policy

Green mentioned that DHS is now in the process of revising the traumatic incident management policy. The new policy recommends that components have a comprehensive traumatic incident management strategy in place. The intent is not to focus on the traumatic incident but instead to have a strategy in place that develops the capacity of the organization over time. Current activities are centered on getting the peer-support programs up and running. The policy also suggests chaplaincy as part of the plan. DHS struggles with providing mental health support because most of the services for employees are contracted to outside vendors. As a result there is little integration of mental health support that is meaningful for the organizational and individual resilience. The new policy recommends a more integrated approach to the EAP, peer support, chaplaincy, and any other pieces chosen to complete a coherent strategy. Green noted that writing a policy is the first step, but unless the policy is implemented, it is a waste of time. At the moment all of the components are interested in peer support and chaplaincy. However, without the evaluation piece the programs will continue to be inconsistent,

and it will be difficult to understand their effect on individual and organizational resilience.

Ombudsman

The creation of an ombudsman role had come up as a possibility, commented Green. This role would offer employees experiencing problems at work an alternative dispute resolution process. Other federal agencies have models for this approach, and the role often includes remediation for workplace violence, harassment, denial of flexibility, and working conditions.

Buddy Check Training Collaboration

Based on lessons learned from the DOD and Army studies, DHSTogether collaborated with the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center to adapt the Ask, Care, Take Action model to the law enforcement culture and language. As a result, trainees going through basic training courses at the training center (criminal investigator, immigration and customs deportation, land management, and uniform police training) are now getting a suicide prevention buddy check program in their initial training.

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY’S HUMAN CAPITAL FRAMEWORK

Vicki Brooks is the Deputy Chief Human Capital Officer at DHS. Based on her experience at the DOD during its joint integration of the military services, DHS has a formidable task ahead of it to coordinate and unify the component agencies. The integration process at the DOD took 40 years.

Brooks quoted an online article from Rachel Zupek and comments from human resources consultant Cy Wakeman that assert that grade-point averages (GPAs) only reflect success in a controlled environment and are not always an accurate predictor of effectiveness in the real world. Instead, candidates with a demonstrated ability to capitalize on opportunities presented by change are resilient and more attractive to employers (Wakeman, 2009). Brooks notes that this article reflects the important of resilience in the workplace. DHS employees do not work in

controlled environments and often face stressful situations; it is therefore necessary that the workforce be resilient.

DHS has a workforce of 230,000 employees whose primary mission is to secure the nation from threats. These employees are in high-stress jobs ranging from aviation, border security, emergency response, cybersecurity, and chemical inspectors. DHS’s strongest assets are the men and women who are on the front line every day fulfilling the department’s mission. DHS’s ability to protect the nation depends upon a healthy and operationally ready workforce.

It is a challenge, considering the existing human capital, to foster and sustain a resilient and confident workforce in order to ensure that employees are able to carry out their duties in the face of their demanding mission. Brooks was asked to discuss the constraints and complexities of managing human capital components in DHS, program outreach to employees’ family members, and how EAP contracts are structured to fit the needs and cultures of DHS employees.

Centralization of Human Resource Functions

DHS celebrated the eighth anniversary of its creation in March 2011. DHS was formed by placing 22 different federal departments and agencies into a new unified and integrated department. Brooks commented that “integrated, unified, one DHS” is easier to say than to do. Besides the component agencies that existed before DHS, new agencies were created from scratch, such as the TSA. DHS is a young department and is going through a maturation process that includes working toward consistency and standardization of employee and human capital programs. It is important when discussing the components individually to also recognize that they fall within a broad umbrella. However, in some cases they may still feel that they have a separate mission and a different culture.

As the department works to integrate the different components and their leadership, DHS faces challenges not only in resilience programming but also in changing the paradigm and shifting cultures throughout the department. To illustrate this point, Brooks cited a memorandum from the deputy secretary to the component heads dated January 15, 2010. The memo focused on the consolidation of the 22 agencies under one unified organization, which includes human resources, processes, people, and technology. DHS has inherited a wide variety of human resources processes and information technology systems. These systems now inhibit the one DHS culture and negatively impact operating cost.

The memo went on to say the department can no longer sustain a component-centric approach when acquiring new or enhancing preexisting HR systems, and that components now have to have the Chief Human Capital Office’s approval before updating or acquiring new human resource systems. Brooks noted that this memo came out 7 years after DHS was formed.

There is a thin line between centralization and component autonomy for management functions and human capital functions. Each component has a human capital director or human resource director who is typically at the senior executive service (SES) level. Within the subcomponents there are also shadow human resource organizations. Given this environment, there is constant tension around what makes good business sense to centralize and what makes good business sense to remain autonomous within the components. The SES candidate development programs across DHS are an example. There were separate programs in such components as the TSA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). All of the programs were managed by different components and had different processes and policies, as well as selection and placement criteria. As of 2011, DHS has a single centralized SES candidate development program being managed out of OCHCO, and all the policies and processes are disseminated from OCHCO with input from the components.

OCHCO is more centralized from a policy perspective than from a program perspective. OCHCO sets many policies within human resources. Those policies may evolve into instructions that are then distributed to components. However, components have the autonomy to determine how those processes are implemented within their structure. OCHCO audits these processes on a rotational basis. Generally the audits are performed every 3 years to assure the programs are in alignment with the various established policies and practices.

Employee Assistance Programs

Employee assistance programs and other employee support programs such as work-life programs are part of the complex framework of resilience. Although EAP policy is centralized, OCHCO holds loose accountability over the programs, and each component can decide how it wants to set up its program. The components can determine if the EAP is an internal program within the organization, if it is contracted out, or both. In theory, this allows the components to tailor the EAP to better address

the needs of their cultures and their internal missions. In actual practice, however, the robustness of the services offered in an EAP is often dependent upon budgetary constraints. This is true in other federal agencies as well.

OCHCO is currently updating a DHS-wide EAP policy to increase accountability, consistency, and quality. The components will continue to have some autonomy within their EAPs. These updated policies will establish some standards and allow the audit teams to recognize well-performing programs as well as make recommendations for changes. OCHCO believes there are several good EAPs within the various components. However, the office is often challenged with questions about maximizing the dollars spent across the components for the EAP.

Planning committee member Joseph Barbera wondered if the department had looked at the necessary baseline elements needed to ensure consistency across all of DHS. Is it possible to start building metrics that measure EAP contractors? Brooks responded that the department is not at that level yet, but it is headed in that direction. Green added that the department is currently focused on moving from no consistency to having a baseline expectation of the programs. Barbera commented that OCHCO might consider looking at agencies with similar cultures and matching EAP elements that are appropriate to those groups. Green agreed and noted that individuals from the various components have been informally looking at this issue and sharing information. Barbera noted that the DOD program was developed around a strategic framework that was slowly populated.

EAP Utilization and Stigma

Stigma is a significant issue with EAP utilization in Brooks’ experience. Leadership, managers, and employees generally do not interact with the EAP unless there is a disciplinary issue. This perception of the role of EAPs can be changed by educating leaders and employees. Mugno asked if there are any real or perceived career consequences associated with seeking EAP services. Green noted that it is hard to comment on possible real consequences because it is not something that is tracked given the clear line between the EAP and the organization. The EAPs provide general statistics about the number of people seeking assistance and for what, but there is no identifying information. EAPs will follow up with individuals as a service quality survey, but they do not ask information beyond that. Components with internal EAPs tend to

have been in place for a long time. EAP providers are embedded in the culture and are seen to be relatively safe for employees.

Improved marketing is part of the resilience initiative to address the possible negative perceptions about seeking assistance, and it appears to have made a difference. The DHS-wide marketing program has tried to communicate the simple message that it is okay to ask for help. EAP managers have reported a surge of utilization after the marketing messages went out. Over time, however, there has not been a huge effect on the overall utilization rates. The intention is that these messages will be part of annual trainings and happen more broadly on an ongoing basis throughout the organization.

Program Outreach to DHS Employees’ Families

There are programs and services such as the EAPs that are available to family members. The Office of Personnel Management recently broadened the definition of the term family member, and DHS is updating its policies to the broader definition. Although the department has access to employees’ personal identifier information, direct outreach to family members is difficult because of current limitations in and accessibility to data. As with all employers, DHS has to delicately balance privacy concerns of employees and their family members with the need for access to data. There have been several changes in the types of information that can be included on forms to protect the privacy of the employee and his or her family members. As mentioned before, there is a wide range of data systems in place throughout the agency, which creates logistic and technical issues. Employees sometimes do not provide information about family members. All of these issues create obstacles to identifying and reaching out to family members.

OCHCO has limited outreach resources. DHS has a website that family members have access to, and it encourages components to do a broad spectrum of marketing. Additionally, the department is moving toward an automated system that will allow DHS employees to include contact information of family members. If there is an emergency, the system will send e-mail alerts to the employees and their family members.

Sundwall asked about the types of services available to family members compared to employees. Green commented that family members have access to the same EAP services as an employee. These services include financial and legal assistance as well as personal, marital, and family counseling. OCHCO has established a policy that all eligible individuals

have access to at least six counseling sessions with the EAP. All but one of the components already has a model with six or more sessions. If the individual needs additional assistance after the six sessions, he or she receives a referral for long-term counseling. Green responded that this model is fairly standard in the federal government. The rationale behind it is that if a family member is struggling, the employee’s effectiveness at work will be affected.

UNDERSTANDING THE EFFECT OF OCCUPATIONAL STRESSORS ON OPERATIONAL READINESS

Mary Kruger is chief of staff for the Office of Operations Coordination and Planning at DHS. This office has three principal functions. Its primary responsibility is running the national operations center, which includes handling information from all the operation components, their state and local counterparts, and law enforcement. The office manages the department-wide efforts to identify potential scenarios and develop plans to synchronize responses to critical incidents such as an anthrax attack, cyberattacks, and so forth. The final piece is to ensure DHS continuity by establishing the processes and systems for appropriate succession planning, devolution, and reconstitution of the government. Prior to joining DHS, Kruger worked for the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Health and Human Services. Because of her inter-agency experiences, her remarks focused on issues related to holding high-level security clearances and working in an operations center.

Working in an Operations Center

The national operations center has representatives from all of the components of DHS, interagency representatives from the Department of Energy and the National Security Agency (NSA), as well as state and local law enforcement officers. The center runs 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year with rotating shifts of personnel. More than 500 personnel work in the operations center, including detailees from other agencies and law enforcement components. Almost everyone in the operations center has at least a secret clearance; more than half have or are eligible to have clearances above the secret level. Part of the operations center is called the intelligence watch and warning. To work in that

group it is necessary to have a top-secret or higher clearance. Those people routinely see information that could be very disturbing.

The pace at the center can go from tedious and monotonous to extremely high pressure and fast paced in a matter of moments. Operations center staff work on a shift schedule that can contribute to burnout. Shifts change, and within a given month somebody can be working an early shift, a mid shift, and a late shift. Staff members have difficulty adjusting their bodies and their schedules to shift changes. The stress of such shift work can affect performance and resilience.

The stress of holding a clearance is caused by more than seeing disturbing information. People working in this field ask themselves what the next event is going to be and how will they react, particularly since 9/11. How does one decide between job and family? Which of them comes first?

Individuals can affect how the center operates. The more stress people experience, the more frenzied the operation is likely to be, and as a result there are more chances to make mistakes—such as inadvertently sharing information with a colleague or family member. The reality is that a mistake made under pressure can endanger one’s clearance. If a staff member loses his or her clearance, then he or she could lose his or her job and potentially risk an entire career. All of these issues relate to resilience.

Balancing Security and Personal Privacy

Individuals with high-level clearances make a decision to give up a certain degree of privacy and confidentiality. Applicants are required to disclose a great deal of personal information about medications, counseling, and whether they have been abusing prescriptive medications, alcohol, or illicit drugs. The applicant’s past is delved into in ways the applicant may never have considered or understood. Because people are required to report seeking counseling to the security office, they are wary about how that can affect their positions. Therefore, people avoid counseling whether it is through the EAP, the family doctor, or a social worker. Kruger was aware of people who sought help with external providers and paid out of pocket to keep it from going on their record.

Training in Operation Centers

A good deal of time and attention is spent on training in Kruger’s office. The training program for operations center staff is very intense. For every level there is job-specific training, as well as security training on handling classified information. There is a strong team environment. The reality is that even with training, people who work for years in high-stress environments make mistakes. These mistakes are considered infractions and go into the staff member’s record.

Many people who start their careers working in operations centers can move up quickly through the ranks to the GS-15 level. The pace of work at a center makes it difficult to obtain training in other fields and skills. Because of the specificity of training and the work in an operations center, it is difficult to transition to another substantive job outside the center. When and if staff members are burned out by the work in the center, they can face very limited options externally.

Kruger commented that the operations center does not have any support services in place specifically within her office. Although she can refer people to the EAP, because of privacy and confidentiality policies, supervisors are not supposed to follow up on whether the staff member sought out those services. Kruger noted that these gaps in training and support create a Catch-22 for the employees.

COMMUNICATING THE SECURITY CLEARANCE PROCESS AND REQUIREMENTS

Kimberly Lew is chief of DHS’s Personnel Security Division (PSD). The Office of the Chief Security Officer (OCSO) is responsible for putting the policies in place for all of the DHS components’ personnel security divisions. The operational components all have a separate standalone personnel security division, but all of their policies fall under DHS’s OCSO. All of the personnel security offices, except the TSA and Secret Service, share an enterprise-wide tracking system for personnel security determinations. If an individual has a clearance in the organization, then all the security divisions have access to that information, which allows individuals to transfer between components.

Personnel Security Adjudication and Policies

There are two types of personnel investigation in DHS. The first type is the background investigation that everyone who works for DHS is required to undergo. The background investigation is needed to determine the applicant’s suitability and fitness for the position. The second type of investigation is for the subset of DHS employees who also must be investigated in order for a security clearance to be granted.

During the investigation and adjudication, the PSD assesses the individual within a whole-person concept. The process is intended to take a snapshot of the whole person to help the PSD predict future behavior and to see if the applicant is going to be a trustworthy and reliable employee. In investigations that include security clearances, the level and depth of investigation depends on the potential level of clearance.

The applicant completes the Standard Form (SF) 86, which is the questionnaire for national security positions. The security officer uses the information from the form to determine how the applicant fits within the laws, guidance, and regulations. Sometimes investigators seek additional information from the applicant. If something comes up in the applicant’s background, the applicant is given an opportunity to provide information that may mitigate the circumstance or issue. As stated before, if the applicant does not need a security clearance for the position then he or she is still required to have a background investigation.

The investigation for a secret clearance has a 5-year scope. Unlike the higher-level clearances that require physical leads and one-on-one interviews, secret-level investigations tend to use more vouchering and confirming specifics from the forms. For the highest level, a top secret (TS) or top secret/sensitive compartmentalized information (TS/SCI), the PSD conducts a single-scope background investigation, which has a 10-year range. The PSD staff interviews references, the employer, and many other individuals linked to the applicant. If the applicant has had or is having mental health counseling, the PSD staff reach out to the counselor. The applicant signs a form giving the investigator permission to contact the counselor. The counselor is contacted to make sure that the applicant’s condition will not impair the individual’s judgment or reliability to safeguard classified information and material.

Applicant Suitability

All investigations look into the applicant’s suitability. The criteria that must be used for making suitability decisions are listed in the Code of Federal Regulations, Title V, Part 731. The criteria weigh eight factors to determine suitability. These factors are misconduct, negligence, criminal dishonest conduct, making intentional false statements, alcohol abuse, illegal drug use without evidence of rehabilitation, acts against the United States, and whether there is any statutory bar that prohibits the applicant from holding that particular position.

The PSA also looks at seven considerations within the codes. What is the position being applied for? What was the applicant’s conduct during an event in question and how serious was it? What were the circumstances? When did it happen, and how old was the applicant? More leniency might be found if an applicant stole a candy bar as a teenager than if he embezzled money at the age of 45.

The PSA also considers societal conditions. The issue of past drug use is common. Did the applicant experiment with marijuana in college and then never use it again? Or has the applicant continued to use drugs throughout adulthood? Investigators also take into consideration if there is an effort for rehabilitation and if the applicant is in treatment.

Security Guidelines

For applicants that require security clearances, the investigation includes assessing the applicant’s information against the security clearance criteria and guidelines. There are 13 security guidelines, including allegiance, foreign influence or preference, sexual behavior, personal conduct, financial considerations, alcohol and drugs, criminal conduct, handling of protected materials, use of technology, and psychological conditions. The security considerations are very similar to the suitability considerations. How serious was a prior adverse event in the applicant’s life? How recent was the event? Was there rehabilitation? Was the applicant’s participation in rehabilitation voluntary? All of these factors are considered, and every case is viewed on its own merits.

Cases are all built around knowing that sometimes bad things happen to good people, and there are situations that can cause a particular event to occur in a person’s life. Given all these factors, such an event may not necessarily cause an applicant to lose a clearance.

Security Infractions

Lew noted that Kruger’s comment is correct about security infractions. Infractions are noted in an individual’s file, but except for extreme cases, the individual will not lose his or her security clearance because of a one-time infraction. If there are multiple infractions over a period of time in which the individual’s negligence has caused the government to lose classified information, or the individual has disclosed information to unauthorized individuals, that is considered a security concern and action will be taken that may result in the removal of the clearance.

Psychological Conditions

Because psychological conditions are listed as a factor in an investigation, there is some stigma associated with seeking mental health counseling. The latest version of the SF 86 includes a note on the front that says mental health counseling in and of itself is not a reason to revoke or deny eligibility for access to classified information or sensitive position. The SF 86 does not require applicants to report counseling if it is strictly related to marital, family, and/or grief counseling. This also applies to people who are transitioning out of the military.

If an individual has a mental health condition and is in treatment, then that should not affect the individual from obtaining or maintaining a security clearance. However, the individual is at risk of losing his or her clearance if he or she is not in treatment, or not adhering to the doctor’s advice, or a duly accredited medical professional says he or she does not believe the individual can be entrusted with national security information.

Seeking Assistance

The reality is that the PSD wants people to seek the services they need when they need them. The goal is for individuals to seek counseling before problems manifest into behavior that could impact the individual’s security clearance. Lew commented that the security office supports EAPs as an avenue for people to seek assistance. The security office does not obtain EAP records. Lew shared that after the previous chief of personnel security lost her battle with cancer, her office brought in EAP counselors to support the staff. Similarly when people report to the office that they are having financial problems or are undergoing a life change such as a divorce, the PSD recommends the EAP services. The security

office’s primary concern is whether the individual is mentally capable of safeguarding classified information.

In response to a question from Peake, Lew explained that the PSD has never had an EAP contact the security office regarding a concern about an employee. Peake commented that when the military started its EAP, when someone had a problem serious enough that it might affect their safety or the safety others, the EAP sought help for the person through official channels. Lew agreed and added that this type of situation would not go through the security office, and that it would be unlikely to learn about it. At the lower levels it would only occur when the individual was up for a reinvestigation. At the higher security levels such as a TS/SCI, it would come to the security office’s attention when the individual reported seeking counseling. Then the security office would contact the counselor and ask if the person had a condition that would impair his or her judgment to handle classified material. If the answer to that is no, then the person can continue to hold classified material.

RESILIENCE ISSUES IN PROGRAM AND POLICY PERSONNEL PANEL DISCUSSION

Kruger and Lew participated in a panel discussion. Planning committee member David Sundwall moderated the discussion.

Security Clearances

Sundwall started the discussion by asking Lew to clarify the intent of the security process. Lew pointed out that the objective of the process is to ensure that people with the highest integrity work for the department. The investigation and adjudication process is intended to determine which people are not likely to (1) have vulnerabilities that make them susceptible to blackmail, or (2) be persuaded to provide information to inappropriate people or groups. That is why the assessment is targeted at whether the individual should have access to departmental and national security information.

A workshop participant asked how the security clearance process at DHS has changed the ability of disaster response organizations such as parts of the Coast Guard and FEMA to function effectively in their disaster response duties by requiring them to get clearances. Lew did not feel it had changed significantly. Generally the number and type of clearances

is driven by whether individuals need to have access to sensitive information in order to carry out their mission.

Number of Clearances

Kruger commented that she feels there are more high-level clearances in the DHS than are needed. She added that perhaps it would be useful to rethink how to determine who needs clearances and at what levels. As an example, Kruger described a person in the department who was well qualified and suitable for a secret clearance. She was put in for an upgrade to a TS/SCI, and because of how in-depth the TS/SCI investigation went, she was not eligible for the TS/SCI clearance and ended up losing her job altogether. Lew commented that the security office does not determine who needs a clearance and at what level. That is determined by the program office and the manager. She felt that perhaps this was something that OCHCO could look into addressing.

Are there components or units within components that comprise the highest number of individuals with clearances, queried Sundwall. Lew responded that in general the number and level of clearances depends on the mission of the component. For instance, the Secret Service, Coast Guard, TSA, and DHS headquarters have a great deal of staff with clearances. Other components such as FEMA and the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) do not.

Mental Health Information and Clearances

Workshop participant Brian Flynn of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress at Uniformed Services University asked if there was any information on how many clearances have been reduced or revoked as a result of mental health services. Lew replied that she did not have a number but knew that it was very small. There are many cases in which mental health counseling is annotated in the file, but there are very few in which the clearance was revoked as a result. She added that in the 2.5 years she has been in headquarters, she was only aware of one case where a mental health problem triggered a security clearance action.

Patty Hawes, a workshop participant from the National Security Agency, asked if the department performs psychological interviews. Lew responded that it does not do so at the department level, but some law enforcement components have different requirements within the hiring process. The Customs Border Protection (CBP) performs a medical evaluation

that includes a mental health assessment for law enforcement officers as part of the hiring process. That assessment is managed through the Chief Human Capital Office rather than the personnel security office.

Barbera asked if anyone has analyzed the history of those who lost their security clearance because of other reasons such as a breach of conduct or other behaviors to see if mental health issues may have contributed. Lew noted that the security office looks at the whole background to see what issues may have contributed to the behavior. In her experience, the conduct is separate and distinct from any mental health counseling.

Barbera asked what happens if somebody is diagnosed with a severe mental health condition but is currently in treatment and controlled. Lew replied that the level of concern is based upon the severity of the condition. The PSD contracts with an independent mental health professional and occasionally refers cases to the independent professional for a detailed review of the diagnosis and treatment. If there have been lapses in an individual’s treatment, then his or her case will be reviewed.

Mugno asked about the use of the word “strictly” in the note on SF 86 regarding marital, family, or grief counseling and stated it might be understood differently by people. There is often a blurring of issues, such as when marital problems affect one’s work. How does the investigation and adjudication address the fear of potential consequences to clearances? At this point, Lew noted that the PSD does not do a lot of outreach on this issue. Under the whole-person concept, it looks at the individual and makes a determination based on the merits of that particular individual’s history and background.

Stigma, Culture, and Training

Mark Bates from the Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychology and Traumatic Brain Injury commented that from a DOD perspective there is often tension between people wanting to keep their security clearance and job and the value of getting help early and preventing larger problems. Does DHS have any effective anti-stigma efforts at either the enterprise or supervisor level? Lew responded that besides that initial contact, periodic reinvestigation, and some refresher trainings, PSD staff do not have many opportunities for such efforts. Although the personnel security office has EAP posters and promotes the use of those services, currently there are no efforts under way to specifically address misinterpretations and stigma. The security office conducts refresher trainings for

security clearance holders. Lew noted that there appears to be a need for more education on this issue.

Barbera asked if the compartmentalization of information is itself a significant source of stress. Kruger said natural feedback loops are used when threat information first comes in. The first person determines what to share, and at what level. There are levels within the watch center, and there are management levels that feed into that. The senior watch officer on duty is in charge of the watch center, and he or she makes the call about what to do with the information. Afterwards people will know what the outcome of the incident was and their part in it. Training them for what they need to do when the information first comes in is critical.

A workshop participant noted that while people may not be concerned about losing their clearance, they may be concerned that utilizing their EAP will affect their chances for promotion. In the adjudication process, what granularity of information does the PSD pass on to the managers or people who may be involved in promotions? Lew stated that the PSD never shares adjudication information with management at any level. Such information is covered by the Privacy Act. Managers are only told if the applicant has been cleared to enter duty and/or that their clearance has been obtained, maintained, or upgraded.

EAP Models and Counselors

Given some of the situations they might be exposed to while treating a patient, Kruger and Mugno asked if EAP counselors have security clearances. Lew replied that to her knowledge EAP counselors were not cleared. Mugno noted that individuals with high-level clearances might seek assistance, but at the same time such individuals would have to be careful about what they say. Kruger noted that sharing of information was on a need-to-know basis.

Given concerns about security, Brinsfield commented that the NSA’s model is very interesting. Workshop participant Patty Hawes from the NSA explained that the NSA’s EAP office is off site so employees or family members do not have to show their badge or identify themselves when going in for an appointment. The EAP services are not reported into the individual’s security clearance record. The NSA has a separate psychological services unit that investigates any issues regarding mental health issues that may be a detriment to security.

Workshop participant Dan Blaettler from the Coast Guard’s Office of Work-Life noted that his office has been managing its EAP for 15

years as part of the Federal Occupation and Health (FOH). FOH is a consortium of agencies with external EAP contracts. He noted that all licensed providers, including those in an EAP, are required to report if a patient is a threat to self or others, or if there is any kind of child abuse. EAP services are generally not considered psychotherapy, and the provider often does not provide a diagnosis. Instead, EAP services are focused on assessment and possible referral. The therapist or the provider is supposed to assess if the problem can be resolved within the context of the number of allowable sessions. There are usually somewhere between 6 and 12 sessions per issue. If the patient’s needs require longer-term assistance, the EAP provider would refer the patient to another provider. EAP is a problem-focused early intervention.

Blaettler added that the Coast Guard uses critical incident stress management (CISM). CISM allows those involved in critical incidents to go through a debriefing process. The Coast Guard used this tool extensively throughout the Deepwater Horizon incident. He added that the CISM process might be helpful for DHS.

Peer Support

While running the Los Angeles Police Department operations center, planning committee member Cathy Zurn instituted a peer-support program to address concerns around stress. The program gave coworkers an opportunity to speak to each other in a supportive environment. Do DHS’s operations centers have a peer-support program in place? Given the high-stress nature of the centers, a peer-support group could provide an opportunity to discuss the stresses of the job with those who understand it best—coworkers. Kruger responded that there is no formal program in place currently. She liked the concept but was concerned about the issues with information sharing given the nature of the watch center.

Burnout

Zurn asked if there are programs where staff can rotate out of the operations center to reduce burnout and then come back without affecting their careers. Kruger noted the operations center is trying to institute a rotational program where staff can rotate to other parts of the department or interagency. The challenge is that their training as a watch-stander does not translate easily to work as a program officer or policy analyst. Although the department is trying to offer training opportunities, watch-standers

often do not have time to attend the training. The operations center is also instituting a new program where people at the journeyman level rotate through the operations center. They can rotate through other parts of the office or through the department to make the job more fulfilling. The hope is that if the work is more interesting, then individuals will not burn out so quickly, but if they do burn out, then they will have experience doing something else.

Sleep and Rotating Shifts

Peake asked panelists about the impact of rotating shift work on the sleep cycle and resilience, noting that a lack of sleep induces stress and increases the likelihood of burnout. Kruger agreed that sleep is a big issue. In the operations center the work is scheduled on rotating shifts 24 hours a day and 7 days a week. People know this when they take the job. After a few years, however, some people can not do it anymore. The operations center considered if it would be better to always work the same shift, but there have been studies that indicate that rotating shifts are beneficial for training and a whole host of other issues. In the past few years, leadership has encouraged the staff to rest and to take their leave, and people are not allowed to build up overtime. However, at the end of the day the decision to stay in the job is up to the employee. Individuals have to learn how to balance the load. A more detailed discussion of concerns with sleep and fatigue can be found in Chapter 4.

Social Media and Security

Standing committee member Merrie Spaeth asked if the security clearance process assesses people’s computer habits. Given the types of problems the private sector is having with applications such as Twitter and Facebook, are there concerns about the use of social media? Lew responded that the PSD is currently wrestling with social media issues. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence hosted a symposium in September 2011 on social media. It conducted a study and found that there is a good deal of information about operations security released when people Tweet, such as the location of a secured site. Kruger noted that at secure locations social media applications are blocked, and individuals cannot bring in personal flash drives or phones into the facility. Social media is complicated because it is a privacy issue as well. Lew noted that at the moment, the security office does not have the authority

to go into an individual’s Facebook or Twitter accounts. Spaeth added that it might be important going forward to incorporate this issue into security training sessions.

Communication

Green noted that there are potentially many confusing messages about what is and what is not confidential in the clearance process. Employees are told that they have to self-disclose mental health issues to the PSD and that the mental health provider will be contacted to provide some information. When the employee gives the PSD permission to talk to the counselor it is hard for people to believe that this information does not find its way to leadership. Further, health providers have a duty to report certain disclosures that patients make to them. That includes the EAP counselors. If someone makes some kind of credible threat that falls within the constellation of things that have to be reported, EAP counselors are required to report it to authorities. The underlying problem in implementing a resilience program that encourages counseling, peer support programs, and utilization of EAP services is how to communicate coherently with employees.

Kruger noted that when someone takes on a position with a higher-level clearance that person makes a decision to give up some privacy and confidentiality. Rather than saying the EAP is confidential, perhaps the program should focus on encouraging people to use it to get the assistance they need. Peake agreed and added that it might be useful to focus the marketing messages on helping individuals get in front of their problems to mitigate or prevent them from worsening. Peake commented that the military is moving toward embedded mental health providers within the units, which may be a way to consider supporting groups such as operations centers. Kruger added that embedding somebody into the operations center or into any area where people have these high-level clearances could help people feel more comfortable because they are part of the work family.

Brinsfield, K., and A. Green. 2011. DHSTogether operations structure. Presented at Operational and Law Enforcement Workforce Resiliency: A Workshop. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine. September 15.

Wakeman, C. 2009. How does GPA stack up in the real world? Fast Company. June 29. http://www.fastcompany.com/blog/cywakeman/follow-thought-leader/how-does-gpa-stack-real-world (accessed February 15, 2012).

This page is blank