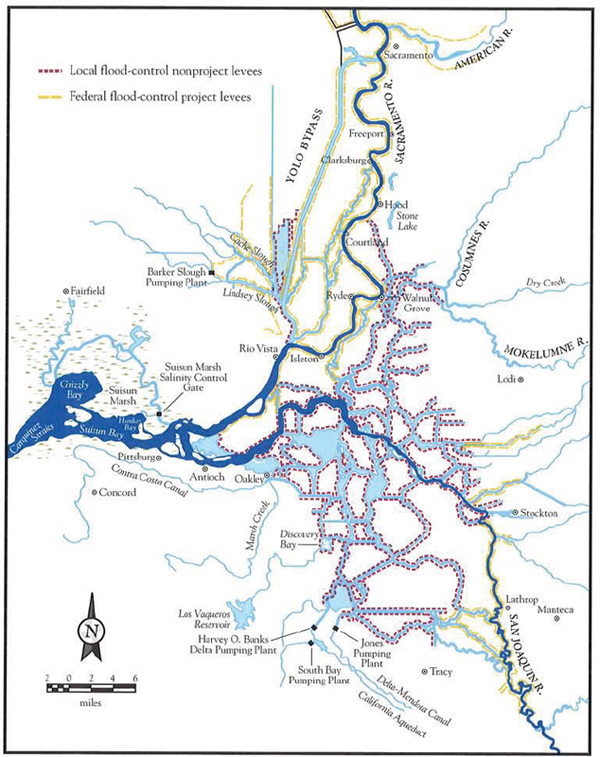

California’s San Francisco Bay Delta Estuary (Figure 1-1) encompasses the deltas of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers as well as the eastern margins of San Francisco Bay. Although the area has been extensively modified over the past century and a half, it remains biologically diverse while simultaneously functioning as a central element in California’s water supply system. The delta system is subject to several forces of change, including seismic activity, land subsidence, sea level rise, and changes in flow magnitudes due to engineering and climate change, which threaten the structural integrity of the delta and its capacity to function both as an important link in the state’s water supply system and as habitat for many species, some of which are threatened and endangered. In anticipation of the need to manage and respond to changes that are likely to beset the delta, a variety of planning activities have been undertaken. In addition, there have been actions taken under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) and companion California statutes, including lawsuits. The net result has been considerable uncertainty and conflict concerning the timing and amount of water that can be diverted from the delta for agriculture and municipal and industrial purposes and how much water—and of what quality—is needed to protect the delta ecosystem and its component species.

The delta is among the most modified deltaic systems in the world (Kelley 1989, Lund et al. 2010). The Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta is an

![]()

1 Much of the following material was adapted from NRC (2010, 2011).

integral part of the water supply delivery system of California. Millions of acres of arid and semiarid farmlands depend on the delta for supplies of irrigation water, and approximately 25 million Californians depend on transport of water through the delta for at least some of their urban water supplies. If California’s population grows from the current 37.25 million to nearly 50 million people by 2050, as projected by the California Department of Finance (2007), there likely will be additional water demands even if there continue to be significant reductions in per capita consumptive uses. In addition to supporting these consumptive uses, the delta provides habitat for animals and plants. Five taxa of fish residing in or migrating through the delta [one steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) population, two populations of Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), delta smelt (Hypomesus transpacificus), and green sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris)] have been listed as threatened or endangered under the federal ESA and similarly listed under the California Endangered Species Act. The delta also supports recreational boating and fishing.

The various activities that have taken place in the delta over recent decades have taken place in a complex and uncertain environment. Those qualities apply to the biophysical environment, including complexities and changes in the hydrologic system, such as interactions of altered freshwater discharge regimes with complexities associated with tidal influences, changes in the composition and numbers of many species, variability and changes in precipitation, and changes in the built environment.

They apply also to the human environment, particularly in growth of the human population, complexities and changes in people’s livelihoods and lifestyles, political changes, financial and economic changes, changes in people’s occupations, changes in technology, and changes in people’s understanding of these systems. Uncertainty is inherent in many of the above factors.

The delta includes the lower reaches of the two largest rivers in California and the eastern estuary and associated waters of San Francisco Bay. Most references to the delta do not include San Francisco Bay itself—typically, the western extent is around Suisun Bay—but hydrologically, chemically, and biologically, San Francisco Bay is an integral part of the system and too often is not considered in analysis of the delta. The Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and their tributaries include all of the watersheds that drain to and from the great Central Valley of California’s interior. The respective deltas of these rivers merge into a joint delta at the eastern margins of San Francisco Bay and estuary. The delta proper is a maze of canals and waterways flowing around more than 60 islands that

are protected by levees. The islands themselves were historically converted from marshlands as agricultural lands2 and most of them still are farmed.

Unimpaired inflows of water to the delta originate in the watersheds of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers. In an average year those flows are estimated to be 40.3 million acre-feet (MAF) or 48.8 percent of California’s average annual total water resource of approximately 82.5 MAF. Of the total unimpaired average inflow, 11.4 MAF are diverted upstream of the delta for agricultural (83.8 percent), urban (15.0 percent), and environmental (1.2 percent) uses. Diversions from the delta average 6.35 MAF, a little more than one-third of all diversions in the Sacramento–San Joaquin system. Diversions from the delta are dominated by the exports to the irrigation service areas of the federal Central Valley Project (CVP) and the State Water Project (SWP), which include southern portions of the San Francisco Bay Area, the western side of the San Joaquin Valley, and much of southern California. Significant amounts of water are diverted to irrigate delta lands, and irrigation return flow is discharged into delta channels. The average yearly outflow from the delta remaining after diversions equals 22.55 MAF (Lund et al. 2010).

The quantities of water reported above are for an average water year, but hardly any water year in California is average. Water supplies are highly variable from one year to another. Thus, for example, in the Merced River, which drains the watershed including most of Yosemite National Park and is a tributary of the San Joaquin River, the average annual flow is 1.0 MAF. Yet the low flow of record for the Merced River is 150,000 acre-feet, only 15 percent of the average flow, whereas the high flow of record is 2.8 MAF, 280 percent of the average flow. The variability in flows, which is characteristic of all of the state’s rivers, is largely a function of the interannual variability in amount and patterns of California’s Mediterranean climate, which has a wet and a dry season with precipitation falling mainly in the late fall and winter months. In addition, there is considerable variability in the proportion of the precipitation that falls in the mountains as snow, which adds to the variability of the hydrologic regime.

Until recently, planning for water shortage was based on a 5-year dry cycle from the 1930s, or on 1977, the driest year of record. However, recent analyses by the California Department of Water Resources (CDWR 2008, 2011) and Hanak (2012) indicate that changes in precipitation resulting from different anticipated climate conditions (see Chapter 4) will affect water availability for all users. Despite statewide conservation efforts, particularly in the urban sector, increasing seasonal restrictions have been

![]()

2 Recent historical ecology studies at the San Francisco Bay Institute are revealing that the original delta landscape was more complex than formerly thought, and had been modified by humans long before the 19th century (http://sfei.org/node/1088).

applied to diversions, although the total amount of water available for delivery under the terms of SWP and CVP water-supply contracts has not decreased. These projects, which export water to regions of the state that have experienced persistent water scarcity for many decades, are particularly important features of the California waterscape.

The CVP withdraws water from the delta and conveys it southward into the San Joaquin Valley through a system of canals built and operated by the federal Bureau of Reclamation and various municipal and agricultural water-user groups. Most of this water is used for agricultural purposes in the eastern regions of the San Joaquin Valley and the Tulare subbasin at the southern end of the valley. Some is contracted for domestic use. The SWP withdraws water separately from the delta and conveys it southward to agricultural users on the west side and at the very southern end of the San Joaquin Valley and subsequently over the Tehachapi Mountains into the conurbation of the South Coast Basin, including Los Angeles and San Diego. The SWP supplies domestic water users in southern California (and domestic use in the southern San Francisco Bay Area) as well as Central Valley agriculture in proportions that are determined in any given year by the CDWR based primarily on water in surface storage and anticipated runoff. Available supplies, especially seasonally, have been constrained in recent years by court decisions mandating additional seasonal supplies for environmental purposes.

Changes in hydrologic and physical conditions in the delta could constrain and threaten the ability of state and federal water managers to continue exporting water in accustomed quantities through the two major projects. This is a concern since the levees, other infrastructure, and the original geomorphology of the delta are eroding. Lund et al. (2010) identify several factors that today pose significant threats to human uses and ecological attributes of the delta, including (1) subsidence of the agricultural lands on the delta islands; (2) changing inflows of water to the delta, which appear to increase flow variability and may skew flows more in the direction of earlier times in the water year in the future; (3) sea level rise that has been occurring over the last 6,000 years and may accelerate in the future; and (4) earthquakes, which threaten the physical integrity of the entire delta system. There is a long history of efforts to solve these physical problems as well as persistent problems of flood control and water quality (salinity). Salinity intrusion from the waters of San Francisco Bay now requires a specific allocation of delta inflows to repel salinity and maintain high qualities of low-salinity water at the western margin of the delta. This management of salinity is accomplished by monitoring and management

of the average position of the contour line of a specified salinity (“X2”).3 Controlling salinity requires outflow releases from reservoirs that could be used to satisfy other demands.

Resolution of these problems is complicated by water scarcity generally and because alternative solutions impose differing degrees of scarcity on different groups of stakeholders. There are additional allocation problems that arise from a complex system of public and private water rights and contractual obligations to deliver water from the federal CVP and California’s SWP. Some of these rights and obligations conflict and in most years there is insufficient water to support all of them. This underscores the inadequacy of delta water supplies to meet demands for various consumptive and instream uses as they continue to grow. Surplus water to support any new use or shortfalls in existing uses are unavailable and any change in the hydrologic, ecological, or physical elements in the delta could reduce supplies further. The risks of change, which could be manifested either by increases in the already substantial intraseasonal and intra-annual variability or through an absolute reduction in available supplies, underscore the existence of water scarcity and illustrate ways in which such scarcity could be intensified.

In its natural state, the delta was a highly variable environment. The volume of water inflows changed dramatically from season to season and from year to year. The species that occupied the delta historically were adapted to variability in flow, quality, and all the various factors they helped to determine. The history of human development of land and water use in the delta is a history of attempts, with varying degrees of success, to constrain this environmental variability, to reduce environmental uncertainty, and to make the delta landscape more suitable for farming and as a source of water supplies. It also included the deliberate and accidental introduction of a large number of species of fishes, invertebrates, and plants into the delta and the surrounding uplands. A full understanding of the historical pervasiveness and persistence of environmental variability underscores the need to use adaptive management4 in devising future management regimes for the delta (Healey et al. 2008).

The history of water development and conflict in California focuses in

![]()

3 X2 is the salinity isohaline—the contour line—of salinity 2. Often X2 is used as shorthand for the mean position of the contour line of salinity 2, measured in kilometers east of the Golden Gate Bridge (across the mouth of San Francisco Bay), but in this report, X2 refers to the isohaline and not its position.

4 “Adaptive management is a formal, systematic, and rigorous program of learning from the outcomes of management actions, accommodating change, and thereby improving management” (NRC 2011). Adaptive management and its relevance to the delta are extensively discussed in that report; the summary reprinted in Appendix B of this report provides a brief version of that discussion.

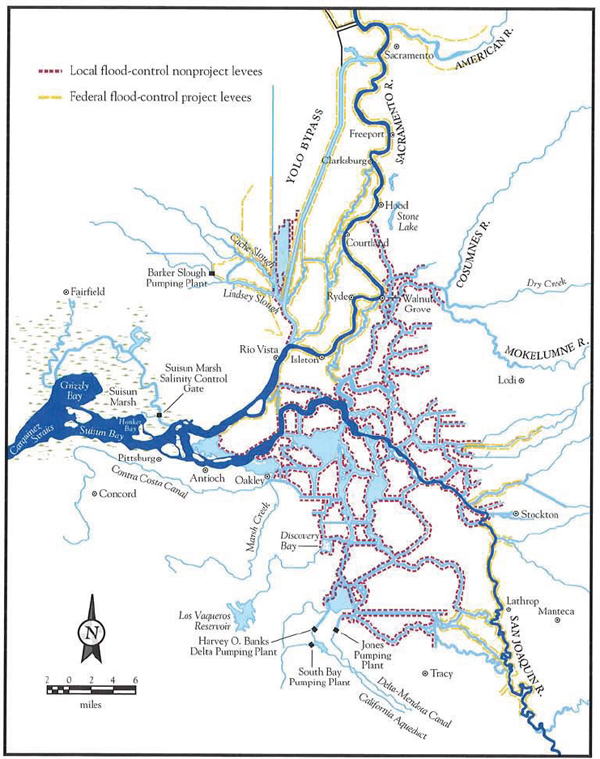

part on the delta. Beginning with the California gold rush in 1848 early settlers sought to hold back the seasonal influx of water and create agricultural lands. The construction of levees played a central role in this effort, an effort that was threatened in the late 1800s and early 1900s by the movement of hundreds of millions of cubic yards of debris from upstream hydraulic mining that passed through the delta. Further work throughout the first third of the 1900s helped to stabilize a thriving delta agriculture (Jackson and Patterson 1977, Kelley 1989). The CVP, begun in the 1930s, and the SWP of the 1960s required conveyance of water from mainstream river channels through the channels and sloughs of the delta to the extraction points located in the southern delta from where water is pumped into the Delta-Mendota Canal (CVP) and the California Aqueduct (SWP) for transport south, as illustrated in Figure 1-2. Once these projects became operational, there was a need to keep the waters of the delta fresh, and salinity control became a problem that was decided by the courts (Hundley 2001, Lund et al. 2010).

In addition to serving economic purposes, delta water has been managed for other purposes. Since the beginning of CVP operations, diversions of water to users outside the delta have been managed to limit salinity intrusion to local domestic water users in the western margins of the delta. Additionally, California’s constitution (article 10, § 2) requires that the waters of the state be put to “beneficial use”; this criterion is subject to judicial review and determination. The enactment of both state and federal environmental laws, including the California Environmental Quality Act and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), have led to greater allocation of natural and stored water to environmental (instream) uses. The importance of environmental uses of water has been reflected further in many state regulatory decisions and, more recently, in judicial interpretations of the federal Endangered Species Act and the California Endangered Species Act. Several taxa of delta fishes that live in or migrate through the delta have been listed as threatened and endangered. The courts became involved and specific water allocations followed from court findings. The maze of federal and state laws as well as dozens of stakeholder groups have combined to create a gridlock that sometimes appears penetrable only by state and federal courts (Lund et al. 2010). As a result, most recent reallocation of water has tended to be based on legislative requirements mandating the protection of individual species rather than the optimization of water allocation among all purposes. The legal backdrop is explored further, below.

There have been several efforts to resolve differences, find areas of agreement, and identify solutions to the problems of the delta and the allocation of the waters that flow through it. These efforts assumed particular urgency as California was beset by severe droughts in the period 1987-1992 and another late in the first decade of 2000. A collaboration of 25

state and federal agencies called the CALFED program was established in 1994; it was unusual in that it had no federal or state legislative mandate (Booher and Innes 2010). It had the mission “to improve California’s water supply and ecological health of the San Francisco Bay/Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.”5 State and federal agencies quickly developed a science-based approach to water-quality standards titled Principles for Agreement on Bay-Delta Standards between the State of California and the Federal Government, otherwise known as the Bay Delta Accord. State and federal agencies with responsibilities in the delta and stakeholders engaged in a decade-long CALFED process, which resulted in the conclusion that the strategy of relying on the delta to convey crucial elements of the water supply to California would continue. CALFED would also be used to attain the four main goals of water-supply reliability, water quality, ecosystem restoration, and enhancing the reliability of the levees (CALFED 2000). CALFED’s functions were taken over by the Delta Stewardship Council under California’s Delta Reform Act of 2009, as described below. Booher and Innes (2010) provide more detail about the formation, functioning, and evolution of CALFED into the current organizational structure.

The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Reform Act of 2009 (“Delta Reform Act”) designated the Delta Stewardship Council as “successor” to the California Bay-Delta Authority (the agency that coordinated CALFED) and provided that the Stewardship Council should take over from the Bay-Delta Authority all of its “administrative rights, abilities, obligations, and duties” (California Water Code § 85034(b)). The Delta Reform Act also specified that the newly created Delta Science Program “shall function as a replacement for, and successor to, the CALFED Science Program” and that the newly created Delta Independent Science Board “shall replace the CALFED Independent Science Board” (California Water Code § 85280(c)).

The Bay-Delta Accord of 19946 and the CALFED process began to unravel around 2003 as environmentalists and water users came to believe that their interests were not being well served and legislators were not satisfied by the CALFED process (Booher and Innes 2010, Lund et al. 2010, Owen 2011). There followed an attempt by the governor to develop a Delta Vision Strategic Plan or “Delta Vision” with the aid of an independent Blue Ribbon Task Force. The Delta Stewardship Plan (“Delta Plan”) resulted from this effort. The Delta Plan is a broad umbrella plan mandated by the California Delta Reform Act of 2009 (California Water Code § 85300) to advance the “co-equal goals” of providing a more reliable water supply for

![]()

5 See http://calwater.ca.gov/calfed/about/index.html.

6 Principles for Agreement on Bay-Delta Standards between the State of California and the Federal Government 1 (Dec. 15, 1994), available at http://www.calwater.ca.gov/content/Documents/library/SFBayDeltaAgreement.pdf.

California and “protecting, restoring and enhancing the Delta ecosystem” (California Water Code §§ 85020, 85054). The act requires the Delta Stewardship Council to “develop, adopt, and commence implementation” of the plan by January 1, 2012, and specifies that the membership of Delta Stewardship Council must reflect broad California water interests. Also beginning in mid-decade, federal, state, and local water agencies, state and federal fishery management agencies, environmental organizations, and other parties began work on the Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP), an early draft of which was the subject of a recent National Research Council report (NRC 2011).

Developing the BDCP has been a large and expensive endeavor (NRC 2011). The BDCP is technically a habitat conservation plan under the federal ESA and similarly is a natural community conservation plan under California’s Natural Community Conservation Planning Act. “It is intended to obtain long-term authorizations under both the state and federal endangered species statutes for proposed new water operations—primarily an ‘isolated conveyance structure,’ probably a tunnel, to take water from the northern part of the delta to the southern thus reducing the need to convey water through the delta and out of its southern end” (NRC 2011). The initial public (November 2010) draft of the BDCP was reviewed by the NRC (2011)7; the summary of that report is reprinted in Appendix B.

All of the above activities have taken and continue to take place in a complex legal environment. Below is a description of the legal backdrop surrounding California water.

Surface Rights

California water law is a unique and complicated system that recognizes both riparian water rights (the system that predominates in the wetter eastern states) and the prior appropriation doctrine (the system that predominates in the arid western states) (Cal. Constitution, article 10, § 2). From time to time, the state legislature has tried to diminish the importance of riparian rights to simplify the legal system but has met with obstacles in the nature of constitutional property rights protections (see in re Waters of Long Valley Creek Stream System, 599 P.2d 656 [Cal. 1979]).

If there is not enough water to satisfy both riparian and appropriative rights, riparian rights must be satisfied first (Tulare District v. Lindsay-

![]()

7 The NRC’s review focused on the use of science and adaptive management in the draft BDCP.

Strathmore District, 45 P.2d 972 [Cal. 1935]). However, in some cases, unexercised riparian rights may not enjoy this superior priority (in re Waters of Long Valley Creek Stream System, 599 P.2d 656 [Cal. 1979]). If surplus water remains, appropriative rights can be satisfied in order of priority.

Riparian Rights

Riparian landowners—those who own property that abuts a natural watercourse—are entitled to make reasonable use of the adjacent water. Riparian uses can be initiated at any time and they are generally not lost through nonuse (some older rights may have been lost under the doctrine of prescription, a type of “squatter’s right”). However, several important limitations apply to riparian rights:

1.Reasonable use: The type of use must be “reasonable.” The amount of use must also be “reasonable” in light of the purpose to be accomplished and in comparison to the needs of other riparian land owners sharing the same water source.

2.Storage: The riparian right allows for the diversion of water, but generally not for its storage for later use.

3. Place of use: Generally, water must be used on the tract of land adjacent to the water source.

4. Shortage: In times of shortage, all riparians must share the loss through pro rata reductions (percentage cutbacks often correlate with the percentage of land owned along the common watercourse). The state constitution restricts all water rights to uses that are reasonable and beneficial (Cal. Constitution, article 10, § 2).

Riparian rights are imprecise. Not only must they be cut back in times of shortage, but the determinations of “reasonableness” are made by courts on a case-by-case, after-the-fact basis when conflicts arise. Thus, it is difficult to know in advance the precise scope of a riparian water right.

Appropriative Water Rights

Water rights may be acquired independently of riparian land ownership under the doctrine of prior appropriation. The primary requirement is that the water be placed to “beneficial” use through a “reasonable” means of diversion. Appropriative rights differ from riparian rights in several important respects:

1. Permit process: Before using water, one must acquire a permit (authorizing the development of a water diversion or project) or a

license (confirming the water right) from the State Water Resources Control Board (“State Water Board”). Early appropriations known as “pre-1914” rights are exempt from the permit scheme.

2. Storage: Appropriative rights may be stored for later use.

3. Place of use: Water may be used on land apart from the place of diversion, and even transported to other watersheds.

4. Shortage: Water rights are administered according to the maxim “first in time, first in right.” In times of shortage, the most senior priority is satisfied before the next most senior user receives any water. This gives rise to the phenomenon of “paper water rights,” under which junior water users may have state-issued water rights that do not yield “wet water” except in years of exceptional precipitation.

5. Nonuse: Because beneficial use is the basis and measure of appropriative rights, they can be lost through nonuse (Cal. Water Code § 1241). At times, this might create a perverse incentive for users to waste water in order to maintain a historic record of diversion not subject to loss through nonuse. To counteract this tendency, 1977 legislation recognizes water conservation as the equivalent to a reasonable beneficial use (Cal. Water Code § 1011(a)).

The priority system provides a measure of predictability lacking under riparian rights. For example, agricultural water users with relatively senior priorities may plant higher priced, permanent crops such as grapes and fruit trees, whereas more junior users might not feel comfortable making an investment in such permanent crops. Despite this relative predictability, appropriative rights can be modified by the State Water Board, which has continuing jurisdiction to modify water permits with conditions to protect other water users and the environment. This authority derives, in part, from California’s rigorous interpretation of the ancient public trust doctrine, under which the state has a duty to supervise flowing waters, tidelands, and lakeshores to protect the public interest in resource preservation, fishing, navigation, and commerce (National Audubon Society v. Superior Court of Alpine County, 658 P.2d 709 (Cal.), cert. denied, 464 U.S. 977 (1983); State Water Resources Control Board Cases, 136 Cal. App. 4th 674 (2006)).

Groundwater Rights

There is no comprehensive permit system for the regulation of groundwater in California, although the State Water Board has some (largely untested) authority to restrict “unreasonable use”; local groundwater districts do engage in planning; and the courts can adjudicate groundwater rights (Nelson 2011). Overlying landowners can freely withdraw the percolating

groundwater (that is, groundwater that does not flow as an underground stream) beneath their property for reasonable and beneficial use. This right, similar to the surface doctrine of riparianism, is subject to the “correlative” right of other overlying landowners withdrawing from the same source.

Water Rights for the Environment

California recognizes “recreation” and “preservation and enhancement of fish and wildlife resources” as beneficial uses (Cal. Water Code § 1243). New water rights may not be appropriated for the purpose of “instream flows,” as recognized in many western states, because the use of water within a stream runs afoul of the traditional requirement of diverting water from the streambed. However, since 1991 state law has allowed existing appropriations (originally including a quantified diversion) to be changed to instream flow purposes. As provided by Water Code § 1707(a)(1), “Any person entitled to the use of water, whether based on an appropriative, riparian, or other right, may petition the board … for a change of purposes of preserving or enhancing wetlands habitat, fish and wildlife resources, or recreation in, or on, the water.” This provision has been used in several cases, including applications in the Sacramento River basin. California has no comprehensive, statewide instream flow program to supplement these privately held instream flow water rights.

WATER RIGHTS AFFECTING THE BAY-DELTA

Water Contracts

The federal Bureau of Reclamation (operator of the CVP) and the State Department of Water Resources (DWR; operator of the SWP) hold appropriative water rights. Like any appropriative rights, they are subject to a variety of permit conditions and other limitations to protect the environment and other water users. These water rights have relatively recent (junior) priorities, generally dating back no earlier than the 1920s. As a result, in drought years, the priority system may limit the water diversions to which the Bureau and the DWR are entitled.

Water contracts add an additional layer of complexity to California’s water rights system. By contract, the Bureau and the DWR have agreed to deliver prescribed quantities of their appropriative water rights to numerous water user groups. Whereas most CVP water goes to agricultural users, urban users are the primary recipients of SWP water. The contracts are not uniform, and some have been amended over time. Many, but not all, contain provisions designed to relieve the Bureau and the DWR of their contractual obligations when the agencies’ water rights are not fully satis-

fied due to drought, permit conditions, environmental regulations, or other factors. A typical provision (often found in para. 18(f) of the DWR’s contracts) might provide that neither the state nor its agents may be held liable for “any damage, direct or indirect, arising from shortages in the amount of water to be made available for delivery … under this contract caused by drought, operation of area of origin statutes, or any other cause beyond its control” (e.g., Tulare Lake Basin Water Storage District v. United States, 49 Fed. Cl. 313 (2001)).

As a result of these factors, there has been uncertainty and dispute over the precise entitlements of those who hold contracts for the delivery of water. The DWR publishes annually a document known as “Table A” that tabulates actual SWP water deliveries as a percentage of 4.133 MAF per year—the maximum amount allocated under SWP contracts (corresponding to the volume of water rights held by the DWR itself for use in the SWP). In its January 2010 draft report, for example, the DWR lists 2009 average annual deliveries as 60 percent of the maximum contract amount. The DWR notes “very significant reductions” in deliveries since 2005. The reductions are attributable, in part, to severe drought, as well as in part to restrictions imposed on the state and federal agencies based on salmon and smelt biological opinions (California Department of Water Resources, Bay-Delta Office, Draft State Water Project Delivery Reliability Report, 2009, January 26, 2010).

Some claim that the maximum amount allocated by contract is not the appropriate baseline because it treats limitations inherent in the California water rights system as extraneous interferences with water rights. Rather, limitations such as the curtailing of junior water rights, water permit conditions, and the public trust doctrine define the contours of the water right. The California Water Impact Network, for example, asserts that “The [SWP] project has never in its history delivered [the full contract amount], and has delivered no more than about 2.6 million acre-feet in its peak year” (California Water Impact Network, California Water Rights Primer: The Monterey Amendments to State Water Project Contracts).

The Environment

The Bay-Delta Plan of 2006 and State Water Board Decision 1641 specify bay-delta flow requirements. In 2009, California passed a comprehensive package of legislative reforms known as the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Reform Act of 2009. Among other things, the new legislation required the SWB to develop new flow criteria to protect public trust resources of the delta ecosystem (Water Code § 85086). On August 3, 2010, the State Water Board issued its final report, Development of Flow Criteria for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Ecosystem. The report concluded

“[t]he best available science suggests that current flows are insufficient to protect public trust resources” and “[r]estoring environmental variability in the Delta is fundamentally inconsistent with continuing to move large volumes of water through the Delta for export.” The recommended flow criteria include “75 percent of unimpaired Delta outflow from January through June; 75 percent of unimpaired Sacramento River inflow from November through June; and 60 percent of unimpaired San Joaquin River inflow from February through June.”

The Water Board noted that its recommendations lack binding legal effect unless and until they are implemented through an adjudicative or regulatory proceeding. The recommendations were intended, in part, to inform the development of the BDCP.

In addition to water rights, including for the environment, actions in the delta are affected by federal and state environmental statutes. The federal ESA of 1973 and 1988 amendments (16 U.S.C. §§ 1532-1544) has had a far-reaching effect through its application to pumping operations as a result of lawsuits as described above. The act prohibits the taking of species listed as endangered, and, by regulation, threatened species are protected as well. It requires federal agencies to make sure their actions, or actions they authorize or fund, are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of listed species or adversely modify their critical habitats. The agencies do this by consulting with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) if they consider the proposed action might imperil listed species, or sometimes if a court requires them to do so as the result of a lawsuit. The requirements and processes of the ESA have been described in detail by the NRC elsewhere (e.g., NRC 1995, 2010, 2011).

Other environmental statutes that have relevance to the delta include the federal Clean Water Act and NEPA and the state Natural Communities Conservation Planning Act, the California Endangered Species Act, and many provisions of the California Water Code.

Given the complex backdrop surrounding the California bay delta and the importance of this water source to human and ecosystem needs, Congress and the Departments of the Interior and Commerce asked the NRC to review the scientific basis of actions that have been taken and that could be taken for California to achieve simultaneously both an environmentally sustainable bay-delta ecosystem and a reliable water supply. In order to balance the need to inform near-term decisions with the need for an inte-

grated view of water and environmental management challenges over the longer term, the NRC addressed this task over a term of 2 years, resulting in three reports.

First, this8 committee issued a report focusing on scientific questions, assumptions, and conclusions underlying water-management alternatives in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (FWS) Biological Opinion on Coordinated Operations of the Central Valley Project and State Water Project (December 15, 2008) and the NMFS’s Biological Opinion on the Long-Term Central Valley Project and State Water Project Operations Criteria and Plan (June 4, 2009). This review, A Scientific Assessment of Alternatives for Reducing Water Management Effects on Threatened and Endangered Fishes in California’s Bay Delta,9 considered the following questions:

• Are there any “reasonable and prudent alternatives” (RPAs), including but not limited to alternatives considered but not adopted by FWS (e.g., potential entrainment index and the delta smelt behavioral model) and NMFS (e.g., bubble-curtain technology and engineering solutions to reduce diversion of emigrating juvenile salmonids to the interior and southern delta instead of toward the sea), that, based on the best available scientific data and analysis, (1) would have lesser impacts to other water uses as compared to those adopted in the biological opinions, and (2) would provide equal or greater protection for the relevant fish species and their designated critical habitat given the uncertainties involved?

• Are there provisions in the FWS and NMFS biological opinions to resolve potential incompatibilities between the opinions with regard to actions that would benefit one listed species while causing negative impacts on another, including, but not limited to, prescriptions that (1) provide spring flows in the delta in dry years primarily to meet water quality and outflow objectives pursuant to Water Board Decision-1641 and conserve upstream storage for summertime cold water pool management for anadromous fish species; and (2) provide fall flows during wet years in the delta to benefit delta smelt, while also conserving carryover storage to benefit next year’s winter-run cohort of salmon in the event that the next year is dry?

• To the extent that time permits, the committee would consider the effects of other stressors (e.g., pesticides, ammonia discharges, invasive species) on federally listed and other at-risk species in the bay delta. Details of this task are the first item discussed as part of the

![]()

8 There were some changes in committee composition after the publication of the first report.

9 Available through The National Academies Press: http://www.nap.edu/.

committee’s second report, below, and to the degree that they cannot be addressed in the first report they will be addressed in the second.

Second, a separate but related NRC panel issued a short report that reviews the initial public draft of BDCP in terms of the adequacy of its use of science and adaptive management—A Review of the Use of Science and Adaptive Management in California’s Draft Bay Delta Conservation Plan.10

The current report addresses how to most effectively incorporate science and adaptive management concepts into holistic programs for management and restoration of the bay delta. This advice, to the extent possible, should be coordinated in a way that best informs the BDCP development process. The present report includes discussion of topics raised in both of the earlier reports but it is not a recap or reissue of either of them.

This report addresses tasks such as the following (from the committee’s statement of task, see Appendix C):

• Identify the factors that may be contributing to the decline of federally listed species, and as appropriate, other significant at-risk species in the delta. To the extent practicable, rank the factors contributing to the decline of salmon, steelhead, delta smelt, and green sturgeon in order of their likely impact on the survival and recovery of the species, for the purpose of informing future conservation actions. This task would specifically seek to identify the effects of stressors other than those considered in the biological opinions and their RPAs (e.g., pesticides, ammonia discharges, invasive species) on federally listed and other at-risk species in the delta, and their effects on baseline conditions. The committee would consider the extent to which addressing stressors other than water exports might result in lesser restrictions on water supply. The committee’s review should include existing scientific information, such as that in the NMFS Southwest Fisheries Science Center’s paper on decline of Central Valley fall-run Chinook salmon, and products developed through the Pelagic Organism Decline studies (including the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis reviews and analyses that are presently under way).

• Identify future water-supply and delivery options that reflect proper consideration of climate change and compatibility with objectives of maintaining a sustainable bay-delta ecosystem. To the extent that water flows through the delta system contribute to ecosystem structure and functioning, explore flow options that would contribute to sustaining and restoring desired, attainable ecosystem attributes,

![]()

10 Available through The National Academies Press: http://www.nap.edu/.

while providing for urban, industrial, and agricultural uses of tributary, mainstem, and delta waters, including for drinking water.

• Identify gaps in available scientific information and uncertainties that constrain an ability to identify the factors described above. This part of the activity should take into account the Draft Central Valley Salmon and Steelhead recovery plans (NOAA 2009), particularly the scientific basis for identification of threats to the species, proposed recovery standards, and the actions identified to achieve recovery.

• Advise, based on scientific information and experience elsewhere, what degree of restoration of the delta system is likely to be attainable, given adequate resources. Identify metrics that can be used by resource managers to measure progress toward restoration goals.

The statement of task focuses primarily on science, and does not ask for policy, political, or legal advice. The report organization does not follow the statement of task because the committee concluded the current organization provides a more logical flow. The factors affecting the listed species are discussed in detail in Chapter 3. Future water-supply and water-delivery options are discussed in Chapters 2, 4, and 5. Scientific uncertainties are discussed throughout the text in Chapters 3 and 4, and the degree of restoration likely to be attainable is in Chapter 4.

The membership of the committee that produced this report overlaps considerably with that of the committee that produced the review of the BDCP, but it is not identical. The committee met three times after the BDCP review was produced; once in Sacramento, California, once in Washington, DC, and once in Seattle, Washington. At its Sacramento meeting the committee included a public session during which it heard from a variety of speakers (Appendix D). The committee was able to review information received by September 2011. The report has been reviewed in accordance with NRC procedures: the reviewers are listed in the acknowledgments.

Booher, D. E., and J. E. Innes. 2010. Governance for resilience: CALFED as a complex adaptive network for resource management. Ecology and Society 15(3):35. Available at http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss3/art35/. Accessed June 4, 2012.

CALFED. 2000. California’s Water Future: Framework for Action. Sacramento, CA: CALFED Bay Delta Program.

California Department of Finance. 2007. Population Projections by Race/Ethnicity for California and Its Counties 2000-2050. Available at http://www.dof.ca.gov/research/demographic/reports/projections/p-1/. Accessed June 4, 2012.

CDWR (California Department of Water Resources). 2008. Managing an Uncertain Future: Climate Change Adaptation Strategies for California’s Water. Available at http://www.water.ca.gov/climatechange/docs/ClimateChangeWhitePaper.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2012.

CDWR. 2011. Climate Change Handbook for Regional Water Planning. Prepared for the United States Environmental Protection Agency and the California Department of Water Resources. Available at http://www.water.ca.gov/climatechange/docs/Front%20Matter-Final.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2012.

FWS (Fish and Wildlife Service). 2008. Biological Opinion on Coordinated Operations of the Central Valley Project and State Water Project. Available at http://www.fws.gov/sfbaydelta/documents/SWP-CVP_OPs_BO_12-15_final_OCR.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2010.

Hanak, E. 2012. California Water Planning: Planning for a Better Future. Public Policy Institute of California. Available at http://www.ppic.org/main/publication.asp?i=902. Accessed June 4, 2012.

Healey, M., M. Dettinger, and R. Norgaard. 2008. The State of Bay-Delta Science, 2008: Summary. Available at http://www.science.cal-water.ca.gov/publications/sbds.html. Accessed April 11, 2011.

Hundley, N., Jr. 2001. The Great Thirst. Californians and Water: A History. Revised Edition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Jackson, W. T., and A. M. Patterson. 1977. The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta: The Evolution and Implementation of Water Policy, an Historical Perspective. California Water Resources Center Contribution no. 163. Davis, CA: California Water Resources Center. Available at http://escholar-ship.org/uc/item/36q1p0vj#page-20. Accessed April 25, 2011.

Kelley, R. 1989. Battling the Inland Sea. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Lund, J., E. Hanak, W. Fleenor, W. Bennett, R. Howitt, J. Mount, and P. Moyle. 2010. Comparing Futures for the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Nelson, R. 2011. Uncommon Innovation: Developments in Groundwater Management Planning in California. Woods Institute for the Environment, Stanford University, California. Available at http://www.stanford.edu/group/waterinthewest/cgi-bin/web/sites/default/files/Nelson_Uncommon_Innovation_March_2011.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2012.

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2009. Draft Central Valley Salmon and Steelhead Recovery Plan. Available at http://swr.nmfs.noaa.gov/recovery/centralvalleyplan.htm. Accessed July 12, 2012.

NRC (National Research Council). 1995. Science and the Endangered Species Act. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NRC. 2010. A Scientific Assessment of Alternatives for Reducing Water Management Effects on Threatened and Endangered Fishes in California’s Bay Delta. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC. 2011. A Review of the Use of Science and Adaptive Management in California’s Draft Bay Delta Conservation Plan. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Owen, D. 2011. Law, environmental dynamism, reliability: The rise and fall of CALFED. Environmental Law 37:1145-1215.