1

The Tornado and Its Effects

POSTDISASTER SURVEY

The findings presented in this report were obtained by a National Weather Service (NWS) team dispatched to Saragosa immediately after the disaster and during a subsequent visit by the senior author of this report. The NWS survey team interviewed four people from Midland, five from Odessa, seven from Pecos, and nine from the Saragosa and Balmorhea areas. The senior author began his interviews on June 1. He conducted most in Spanish. A survey of newspaper articles on the disaster was made to develop questions and to double-check information collected during the field work. Questions about any warnings received by survivors were prepared for use during the field interviews, 1 but they did not prove to be very useful since most of the survivors questioned received no warning of the tornado.

Interviews were conducted with the family heads of 10 of the 51 households untouched by the tornado. Despite efforts to locate those whose homes were destroyed, only three family heads could be located and interviewed; the others had moved out of town. Interviews were also conducted with three adults who were at the community center when the tornado struck; the county surveyor; a deputy sheriff who was involved in the rescue operations; the general manager of the local radio station; the Spanish-language radio operator at work during the evening of the disaster; the general managers of the water, electricity, and telephone companies serving Saragosa; and the clerk of the county court.

THE SETTING

Saragosa is a small unincorporated town in the southern part of Reeves County in southwest Texas. The county is vast in size but sparsely popu-

lated. Its economy is based on agriculture (beef, dairy cattle, cotton, grains, alfalfa, pecans); mineral production (oil, gas, sand, gravel); and tourism. Pecos (population 13,429 as of April 1986), which is 32 miles northeast of Saragosa, is the county seat.

Reeves County is a “western style” tourist area in the Trans-Pecos region of Texas. The local climate is semiarid (average annual precipitation, 12 inches), with low humidity. The dominant physical features of the local terrain are rolling to hilly plains. The Davis Mountains are to the south. Reeves County is bordered on the northeast by Loving and Ward counties, on the southeast by Pecos County, on the southwest by Jeff Davis County, on the west by Culberson County, and on the north by the state of New Mexico.

The precise population of Saragosa at the time of the tornado is unknown. Newspaper accounts of the disaster by Reeves County officials give different estimates. The best available estimate, based on the number and average size of households in the town, is close to 400 people. All but two families in Saragosa are of Mexican descent and between 50 and 80 percent speak Spanish only. Most of the adults work on neighboring ranches and farms or in service establishments in Pecos and the surrounding towns.

THE TORNADO

The records for Reeves County report 20 tornadoes from 1950 through 1986. No tornado-related fatalities are listed from 1916 (when recordkeeping began) to 1986. The lack of tornado-related casualties may be attributed to the low population density of the county. Some local people also believe that the proximity of the Davis Mountains, less than 20 miles south and west of Saragosa, may have been a deterring factor for tornado development in the southern part of the county. In June 1938 Saragosa was severely damaged by a tornado. It was then rebuilt 2 miles to the southwest in what is known as the Riverside area. This was the site that was struck by the May 22, 1987, tornado (Wright, unpublished manuscript, 1989).

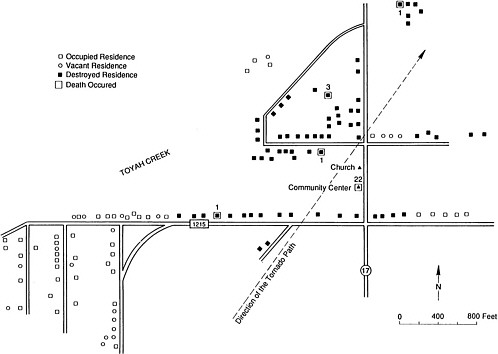

On May 22, 1987, a violent multiple-vortex tornado struck Saragosa between 8:15 and 8:20 p.m.2 Thirty people were killed and 121 injured. Twenty-two of the deaths occurred in Saragosa Hall (see Appendix A ). Sixteen of the people killed were not Saragosa residents. The fatalities that did not occur in the hall included three in a frame house, four in mobile homes, and one in an automobile. All but two of the 30 people who died were Hispanic. Damage estimates ranged from $7.1 million to $8.7 million. The buildings on the extreme east and west edges of the town suffered only minor damage (see Figure 1 ).

The tornado formed about 1 mile southwest of Saragosa near Interstate Highway 10 and moved northeast into town. When the tornado initially

touched down it was fairly weak, with a track width of less than 100 yards. As it moved into town, it quickly strengthened into a large multiple-vortex tornado. This sequence is verified by the tornado track and damage pattern, pictures of the tornado moving into town, and eyewitness reports of “three tornadoes moving in a circle.”

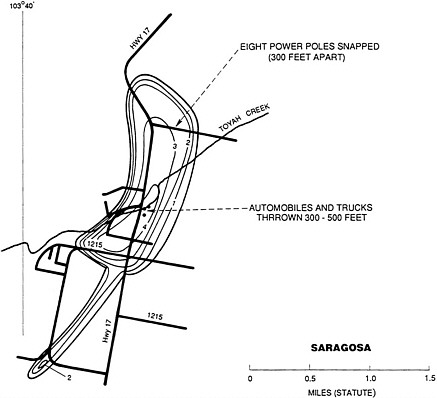

The most intense part of the tornado moved through the central section of town and approached Highway 17, then curved to take a more north-northeast course and weakened slightly. It then followed the highway until lifting. The path length was about 3 miles, with a maximum width of 0.5 to 0.6 miles (see Figure 2 ). Movement of the tornado was estimated to be near 30 mph, although the parent thunderstorm was moving slowly to the northeast. The path of the tornado is reflected in the distribution of destruction. Indeed, the spatial distribution of the tornado's destruction and the deaths it caused can be summarized by a near straight line on the map in Figure 1.

The most intense damage, F4 in strength, occurred over most of the residential and business area of Saragosa. This damage occurred throughout an area three-fourths of a mile long and one-fourth of a mile wide.

FIGURE 2 Path of the tornado.

Structures in the tornado's path were totally destroyed, and no interior walls were left standing. The tornado's force hurled automobiles into buildings and houses; several were found in an open field 300 to 500 feet east of Highway 17.

The tornado developed out of a storm complex that had been active since mid-afternoon over much of Reeves County. Travelers on Highway 17, approaching Saragosa from the north prior to the tornado, reported driving through heavy rain and occasional hail and observed several funnel clouds.

THE DAMAGE

A graduation ceremony at Saragosa Hall for Head Start children from Saragosa and neighboring Balmorhea started at 7 p.m. on the evening of the disaster. Survivors estimate that 80 to 100 people were attending the ceremony (see Appendix B ). Twenty children were on the stage. In the audience were 30 to 40 children, their parents, and other adults.

Saragosa Hall had an area of approximately 2,500 square feet (50 × 50 feet). The south wall and entryway were made of steel-reinforced concrete, while the remainder of the building was frame construction. Most of the hall was destroyed, and the south concrete wall collapsed.

During the graduation ceremony, the space inside the community center was divided into three areas—the stage area, the area adjacent to the stage where the audience was seated, and a refreshments area behind the audience. According to survivors who responded to the postdisaster survey and individuals involved in the rescue efforts, the majority of the victims were killed while seeking refuge by leaning against the walls of the hall. Those who remained in the middle of the hall, and those who found shelter under the refreshment tables, survived. Parents also shielded their children with their bodies.

THE WARNING SYSTEM (OR ABSENCE OF IT)

Despite the lengthy record of official tornado warnings (see Appendix E ), most of the survey respondents received no warning of the approaching tornado. The exceptions were two respondents who saw the warning on English-language television programs. For a number of reasons, the majority of the residents of Saragosa did not perceive the weather to be life threatening or dangerous.

Absence of Bad Weather

The weather conditions in Saragosa during the afternoon of May 22 and shortly before the tornado struck were normal. There was no rain, and the

wind was calm. The survey respondents said they could see rain in the direction of Pecos (northeast), but the sky was clear over Saragosa and in the opposite direction (southwest, toward Balmorhea). In the absence of bad weather, people went about their business in the usual way. None of the survey respondents had previous experience with tornadoes.

Absence of Clear Geographical References

The emergency weather announcements on radio and television made reference to geographical locations in Reeves County that were not relevant to the Spanish-speaking people of Saragosa. Two of the survey respondents said they saw the official emergency weather announcements on television but were unclear if the warnings applied to them. The vast size and sparse population of Reeves County probably contributed to the ineffectiveness of the announcements in eliciting widespread protective responses. The broad geographic locations used in the emergency weather announcements were difficult to interpret by the people of Saragosa. The announcements would have been more effective if they had included the names of the towns at greatest risk.

Absence of Public Warning Systems

There were no sirens, emergency public warning system, or disaster awareness program in Saragosa on the day of the tornado. Every survey respondent stated that a warning was not directly communicated to the citizens of Saragosa by public officials or community leaders. The survey respondents did not receive warnings from police and sheriff 's officers, firefighters, highway patrol officers, or representatives of other official agencies.

The reasons for this lack of contact between Saragosa officials and citizens are not clear. It was probably caused by the absence of disaster awareness and planning alluded to earlier, the urgency of the impending disaster (there was at most 20 to 22 minutes to learn of the danger), and the lack of a tradition of public service to the people of Saragosa. Saragosa is unincorporated, and its citizens believed that the absence of warnings by officials mirrors the structure of social stratification in the county. One survey respondent complained that Saragosa had been systematically ignored by public agencies; it will be interesting to see if this issue becomes an important source of controversy during the reconstruction of the town.

The tornado warnings that the survey respondents did receive came from people who saw the tornado approaching and alerted their family and neighbors. In addition, motorists along Highway 17 alerted citizens to the approaching danger by honking their horns. These warnings were taken seriously and were effective in eliciting protective actions. However, they

occurred very close to the time the tornado hit (in most instances less than 2 minutes), so the range of safety options available was quite limited. Those alerted at the last minute either stayed in their houses, moved to a neighbor's house that they perceived as being safer than their own, or tried to escape the tornado by car. A number of motorists along Highway 17 sought shelter beneath a bridge overpass where Highway 17 and Interstate 10 intersect. Many drivers demonstrated correct safety procedures and abandoned their vehicles for drainage ditches along the road. At least one car stopped at a tavern in Saragosa, and the passengers sought shelter inside. The tavern lost its roof, but the occupants survived.

Although no official warning reached Saragosa Hall, the people there were warned of the approaching tornado by a man who rushed into the building, grabbed his son, and fled in his car. It appears that the consensus of the others was to remain in the hall since they thought, justifiably, that it was one of the best-built and strongest buildings in Saragosa. Indeed, most of the houses in Saragosa are made of adobe or have wood frames; there were very few substantial housing structures. Clearly, adequate public shelters and warning systems utilizing sirens or other means of warning diffusion are needed. Neighbor-to-neighbor warnings cannot be the only public method of alerting citizens to impending hazardous weather.

Absence of Warning on Cable Television

The English-language television stations broadcast the tornado warnings. However, the citizens of Saragosa acquired cable television service only 5 months earlier. The cable service includes Univision, the popular Spanish-language channel. Reportedly, during the evening of the tornado many of the televisions in Saragosa were tuned to this channel. However, Univision did not carry warnings of the tornado, as did the local television stations. Many lives might have been saved if emergency weather announcements had been transmitted on the Univision channel. An effort to see what can be done to provide this service to the Hispanic community is definitely needed.

Absence of Pretranslated Warnings

The local radio station in Pecos serves the town of Saragosa. On the evening of the disaster, the station's operators broadcast weather warnings in Spanish and English. The radio operators were able to respond almost immediately to the impending threat of the tornado. The Spanish-language operator who participated in the emergency broadcasting estimates that the first warning was broadcast by 8:00 p.m. and that emergency warnings in both languages went out every 6 minutes thereafter. Since the tornado

struck Saragosa about 8:20 p.m., it is probable that the Spanish-language radio emergency warnings were broadcast three times before the electricity was cut off and radio reception was blocked in Saragosa.

The radio operator on duty cannot remember with certainty how he translated the emergency tornado warning he received from the NWS office in Midland. The emergency weather messages he received were teletyped in English, so he had to translate them into Spanish first. He thinks that he probably said “aviso de tornado,” followed by the rest of his translation of the message. An accurate translation of the tornado warning was rendered difficult. The urgent need to get the message on the air, coupled with the necessity of selecting the correct Spanish words to convey the technical content of the message (for instance, the difference between watch and warning had to be preserved in translation), caused some confusion.

In retrospect, the radio operator's use of “aviso” probably was not correct, for the word means to “give news, advice, or information.” The technical meaning of the word “warning,” representing a “materialized, impending disaster,” has no direct translation into Spanish, and its meaning is not conveyed by “aviso.” Perhaps a phrase such as “¡cuidado! peligro de tornado” (translation: caution . . . danger from tornado) would have been more appropriate.

It would be a significant improvement if emergency weather announcements could be translated and made a part of disaster preparedness programs available to Spanish-language radio operators throughout the country. Standardized, officially approved, Spanish-language translations would make it easier for Spanish-language radio operators to maintain uniformity, exactness, and accuracy with the meaning of the original English-language messages.

In their report on American minority citizens confronted by natural disasters, Perry et al. (1983) found that their Mexican-American respondents preferred radio over newspapers and television as a source of disaster preparedness information. This finding adds credence to the necessity of effective emergency weather radio messages for the Hispanic community in the United States.

NOTES

1. Questionnaire is available from B. E. Aguirre on request.

2. Determination of tornado damage is based on the Fujita scale. A tornado is defined as a small-scale columnar vortex, often originating from a cumulonimbus that causes damage of scale F0 or higher. The Saragosa tornado was rated F4 (207 to 260 mph according to the Fujita scale).