8

Posteruption Hazard Watch and Disaster Planning

RISK AND RISK INFORMATION

The November 13, 1985 eruption of Nevado del Ruiz was one in a series of prolonged volcanic and seismic events suggesting that magma is moving near the surface of the volcano. During the study team’s visit in early 1986, geologists from INGEOMINAS, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Observatorio Volcanológico de Colombia (Colombian Volcano Observatory) in Manizales all concurred that the risk of a future eruption of Nevado del Ruiz—as judged at that time—was high and that the volcano should be regarded as very dangerous. Thus, an effort to monitor Ruiz was begun after the eruption in 1985, employing telemetered seismic and ground deformation networks centered at the Manizales Observatory. The observatory was declared a permanent international volcano observatory by the Colombian government in early 1986 (Herd, 1986).

Geologists were aware that Ruiz had erupted ten times in the past 10,000 years or so, and that these eruptions have typically triggered lahars or mudflows. However, direct seismographic measurements of the Ruiz volcano date back only to July 1985, when four portable seismographs were installed (Murray, 1986).

The lahars of November 13, 1985 that struck the towns of Armero and Chinchina were obviously devastating. Nonetheless, after the eruption and subsequent ice melt that spawned the lahars, about 90 percent of the mountain’s original ice cap remained intact. Although it remained difficult for geologists to precisely predict the next eruption of Ruiz, a variety of factors in 1986 suggested that another eruption was likely. These factors included the presence of seismic activity, mountain deformation, cracked glacial segments, and melted glacial ponds. In addition, the sizeable ice cap that remained on the

mountain and the existence of cleared channels through which future lahars could move quickly indicated that the risk imposed by additional lahars could be high. Geological and seismological data on the activities of the volcano gathered in late 1985 and early 1986 at the Manizales Observatory also indicated that the volcano had a very high probability of another eruption in the then not-too-distant future, although the magnitude and timing of such an eruption were clearly unknown.

The possibility of further eruption of the volcano created the potential for a second major disaster with an even higher death toll than the 1985 incident. Using population and other data from township and risk maps, the study team estimated in 1986 that 50,000-80,000 lives could conceivably be at risk should the volcano erupt again. For example, segments of the population in the towns of Honda, Mariquita, Ambalema, Chinchina, Herveo, Villa Hermosa, Salgar, and La Dorada were all at risk. Some of these towns were close enough to potential lahar tracks to be struck within about one-half hour after an eruption; others would not be reached by the lahars for three and one-half hours or so; still others lie in between these two estimates.

The danger posed by a post-1985 eruption of Nevado del Ruiz resulted in a major effort in the state of Tolima to define future risk, to generate useful public information about this risk, and to undertake emergency preparedness and mitigation measures. The potential zone of ashfall, for example, had been estimated to be 10 km in radius. Since no real warning would be possible for those in this impact zone, the government endeavored to relocate the 5,000 or so people who resided there. In addition, INGEOMINAS has sought to research and document the last major eruption of the volcano (Espinosa, 1986), and a simplified map of volcano/lahar risk ( Figure 4.1 ), prepared before the November 13, 1985 eruption, was widely disseminated in towns at risk. This was an attempt to illustrate danger zones and to serve as a basis for enhancing public awareness and for encouraging preparedness and emergency planning for the many areas at risk that are not slated for relocation.

EMERGENCY PLANNING FOR WARNING AND EVACUATION

In the wake of the Armero disaster, Colombia established a plan for the warning and evacuation of threatened areas in the event of another eruption of Nevado del Ruiz. The basis for this planning effort was a 1985 United Nations guidance manual entitled Volcanic Emergency Management (UNDRO, 1985). This text outlined topical planning areas, including time-phased response, identification of hazard zones, population and property census, identification of safe transit points and refuge zones, evacuation route identification, means of transport, refugee accommodation, rescue and medical

aid, security in evacuated areas, alert procedures in government, formation and communication of public warnings (including sample wording of messages), and the review and revision of plans.

According to the early 1986 Colombian emergency warning and evacuation plan, the Observatorio Volcanológico de Colombia in Manizales was charged with monitoring the volcano for an eruption or signs of an impending eruption. When an eruption was detected or when the risk of an eruption was seen as high, the Observatorio planned to notify the Colombian president. The president, it was planned, would operate through the National Emergency Committee (COE)—Comité Operativo de Emergencia—which was established by the federal government after the November 13, 1985 eruption.

Housed in Bogotá and headed by a representative of the president, COE was an integration of many agencies and departments, including INGEOMINAS, the Army, the Red Cross, the Colombian Civil Defense, the governor of Tolima, and local police and fire departments. The COE was subject to some oversight from Resurgir—the general oversight agency that was responsible for ensuring that all necessary volcano-related activities were assigned to the responsibility of an appropriate organization. The COE was a central link in emergency evacuation planning since it was the sole body with the charge and power to make evacuation decisions should the volcano erupt again. If such a decision were made by the COE, it would then be directly communicated to Civil Defense.

The Colombian Civil Defense (CD) is located in the Federal Ministry of Defense. It was created in 1950 and restructured in 1971. In 1986, the Civil Defense consisted of a headquarters in Bogotá, offices in most cities throughout Colombia, and over 45,000 volunteers across the country. The organization had a general goal of “service to the community” in times of disaster. Specifically, it was charged with the training of people for disaster response, the overall prevention of disasters, the reduction of disaster impacts, the provision of assistance throughout all phases of disasters, and the coordination of other organizations involved in disaster response. Civil Defense in Bogotá was the organization that would receive any evacuation decision from the COE and initiate action. Thus, CD would begin the chain of communication of the evacuation decision through appropriate organizations to the public at risk in the set of towns in the State of Tolima previously listed.

The planned chain of interorganizational communication was as follows: Civil Defense would inform the governor; the governor would then inform radio and television stations, as well as the mayors of all towns in which some risk existed; the mayors would then inform their police departments; the police would inform siren keepers in their town (the plan specifies one siren keeper in each neighborhood of each town); and, finally, the media and siren keepers would inform the public of the need to evacuate.

The mix of available sirens was varied: some were electric, some were

battery operated, and yet others were hand cranked. It was planned that the public would gather water and supplies and then evacuate. Although television stations go off the air at midnight, they had agreed to stay on the air if they were needed as part of the warning system.

The communication hardware available to facilitate the interorganizational communications specified in the plan was varied. Mayors had teletype machines in their offices over which they could receive communications from the president about the need to evacuate. This was supplemented by telephone links and, for local use, portable two-way radios that officials carried with them at all times.

An additional contributor to the warning and evacuation system was the network of volunteer river observers that had been established after the 1985 eruption by such organizations as CD and the Observatorio Volcanológico. These observers agreed to monitor the rivers between the volcano and the towns at risk to detect lahars and communicate information about them.

PUBLIC EDUCATION

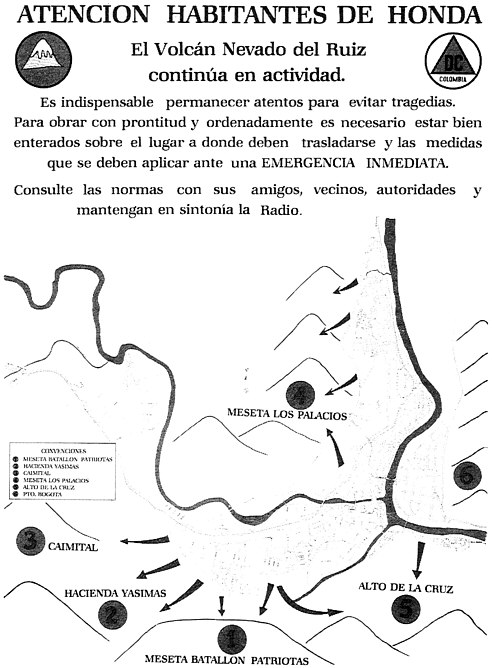

A public education campaign was also under way in early 1986 in the Ruiz area to educate the citizens in the towns at risk. First, schools educated students about volcanic hazards in general and, specifically, what to do if Nevado del Ruiz erupted. Second, the Civil Defense ( Figure 8.1 ) and the Red Cross both printed and circulated thousands of flyers to the public about the volcanic hazard, informing them that they should evacuate when they heard their neighborhood siren. Third, hazard maps in the form of posters ( Figure 8.2 ) were prepared for towns at risk to illustrate appropriate protective action in response to hearing sirens, that is, evacuation to high ground. There was opposition in a few communities to posting these maps, since some local merchants were concerned that such maps might depress the local economy. Finally, evacuation route markers were painted on buildings in towns at risk to illustrate proper egress from danger areas if sirens were heard.

PUBLIC RESPONSE TO HAZARD WARNINGS

As of February 1986, when the study team visited, the warning and evacuation system set in place in the Ruiz area had been activated twice since the November 13, 1985 eruption. In both instances the public response was disappointing. The first instance was a practice drill in which no risk was present, but the siren system was activated to test public response. The sirens were sounded at midnight and the public had no way to know that the event was an exercise. Nonetheless, few residents evacuated.

The second instance was an actual evacuation decision made by the Comité

COMMENTS

In the first few months after the 1985 eruption, the people of Colombia did much to draft, refine, and implement an evacuation/warning system in preparation for a future eruption of Nevado del Ruiz. However, the study team detected two potential flaws in the evacuation/warning system as it was conceived in January 1986. First, the warning system could not work quickly enough to relay a timely warning message to all those who must evacuate. Second, the type of warning then planned to be issued would not be effective enough to convince those who should evacuate to actually do so. Fortunately, work in the field of emergency planning (cf. Mileti and Sorenson, 1987; Perry, Lindall, and Greene, 1981; Mileti, Sorenson, and Bogard, 1985) was available that was useful to address these problems.

The January 1986 warning system in Colombia was designed to pass warnings from scientists to the public through many governmental and bureaucratic levels. As discussed above, the system was activated on January 4, 1986, when a minor eruption occurred that was marked by ash emitted from the summit. Fortunately, no deaths occurred, since this eruption was not accompanied by the emission of pyroclastic flows such as those that triggered the disaster of November 13, 1985.

In the January event it took three hours for the warning message to reach the public. However, some endangered communities could have been affected within 30-45 minutes of an eruption, and most towns at risk would be affected within 2-1/2 hours. Thus, in the minds of the study team, the delay in warning presented obvious problems in the event of a future major eruption.

Plans as of January 1986 called for initiating public evacuation by evacuation warnings, including sirens. Extensive evidence from past evacuation research demonstrates that sirens, even when preceded by elaborate public education before the time of evacuation, are not enough to convince people to leave their homes. Not surprisingly, the evacuation warning prompted by the January 4, 1986 event resulted in little actual evacuation. In light of this research, the study team, through the National Research Council’s Committee on Natural Disasters, issued a brief report in 1986 (Mileti et al., 1986) to the relevant Colombian agencies containing recommendations on how to

plan for more effective and timely warnings in the Ruiz area, as well as other pertinent recommendations. The text of this report is reproduced in Appendix B . What to say, what not to say, and how to say it are well understood by the research community dealing in emergency planning and are of dramatic importance in increasing the probability of effective evacuations.