5

The Truckee-Carson Basins in Nevada: Indian Tribes and Wildlife Concerns Shape a Reallocation Strategy

The arid lands of the Truckee-Carson basins of western Nevada are in transition: urbanization is increasing and the agricultural base is declining. Significant amounts of land are being allocated to the preservation of Indian cultures and wildlife habitats. The area 's transition mirrors the land use changes that are occurring in many areas and represents another stage in the constant redefinition of the West (Athearn, 1986).

The Truckee-Carson transition is characterized by creative use of water transfers to solve the intense water allocation conflicts that have arisen between traditional and nontraditional users. Water use conflicts are being resolved through a combination of litigation, legislation, voluntary transfers, and consensus-building processes. Litigation was used successfully by a relatively powerless minority, an Indian tribe, to change the balance of power among the major water users in the basin. This new balance provided the incentives for most major water users to address basinwide problems comprehensively and to devise creative solutions that should promote both efficiency and equity. In 1990, Congress played a critical role in the long trek from conflict to consensus. The resulting legislation (the Truckee-Carson-Pyramid Lake Water Settlement Act, Title II of P.L. 101-618) may prove to be a model for other western basin settlement acts.

In the past decade, tribal people have been able to gain unprecedented power to influence the water allocation process through fed-

eral environmental and tribal laws, a power denied them in earlier adjudications. Ironically, the Indians' success, along with the ongoing effects of a prolonged drought and of substantial urban and agricultural diversions of water, has contributed to the reduction of a formerly thriving wildlife habitat—the Stillwater Marsh and surrounding Lahontan Valley wetlands. These wet areas have shrunk from some 40,000 acres to a present size of less than 6,000 acres. Wetlands in the Lahontan Valley have been variously affected by the advent of irrigated agriculture: first, by diversion of the historic Carson River flow; then by overdiversion of the Truckee River flow; and, most recently, by efforts to improve the efficiency of the Newlands Irrigation Project. These remnant wetlands were able to coexist precariously with an upstream irrigation district but not with the additional goal of restoring the native fishery. To the extent that the tribe's right to maintain inflows to Pyramid Lake and its fishery is met, there is a reduction in the amount of water available to the irrigation project and, with disproportionate impact, the wetlands.

Water transfers from irrigation to wetland maintenance hold promise for stabilizing the wetland area, increasing the Newlands Irrigation Project's efficiency, and allowing the irrigation economy created in the first half of this century to adjust to the fundamental shift in water resource values that has occurred in the past two decades. The changes occurring in the Truckee-Carson basins suggest that management to promote multiple uses of water and protection of biodiversity is increasingly important. Restoration to the maximum extent possible —including protection of historic ecological diversity and Indian cultural values—is gradually replacing the past emphasis on consumptive water uses.

THE SETTING

Rainfall averages about 9 in. (230 mm) per year throughout the lower Truckee-Carson basins, and the available surface supplies are fully appropriated by adjudications begun in the reclamation era. There are substantial reallocation pressures as urban areas grow, irrigated agriculture continues to decline, and environmental values and the importance of an ecological balance become recognized. This area is a microcosm of the reallocation patterns and institutional changes that are emerging in many areas across the western United States. Both traditional and nontraditional users claim substantial shares of the area's water resources. In addition to the usual conflicts between municipal and industrial uses and irrigated agriculture (both non-Indian and Indian irrigators), there is competition from aboriginal

Indian fisheries, wetland maintenance, and migratory waterfowl production for some 750,000 acre-feet (925,000 megaliters (ML)) per year of decreed rights.

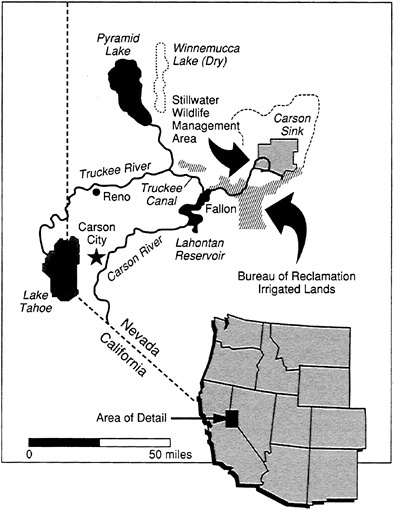

Four major water-using interests compete for the basin's limited supplies (Truckee meadows urban area, Newlands Project agriculture, Pyramid Lake endangered fish species, and the Lahontan Valley wetlands). All users depend primarily on two rivers, the Carson and the Truckee, which drain from the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California into two closed Great Basin systems, Pyramid Lake and the Lahontan Valley marshes, and the Stillwater, Carson sink, and Carson Lake marshes (Figure 5.1). Ground water re-

FIGURE 5.1 Truckee-Carson river basins in western Nevada.

sources are managed on a safe yield basis and can provide only about 20 percent of the supply in the urban area. The rapidly growing metropolitan Truckee meadows area (the towns of Reno and Sparks) dominates the upper Truckee River water use, and 75 percent of the original agricultural uses to the west of Reno have already been converted to municipal and industrial uses. Irrigated agriculture still dominates the use of water in the lower Truckee and Carson rivers, although irrigation in the area has always been marginal in comparison with other areas of the West.

The Truckee basin was the home of one of the chief proponents of a western reclamation policy, Senator Francis G. Newlands of Nevada. Newlands, his fortune in part inherited from his legendary father-in-law, William Sharon, one of the developers of the Comstock lode, came to Nevada in the mid-1880s to manage the family holdings after the Comstock was exhausted and the state began to lose population. Newlands believed that agricultural development was key to the state's future (Truckee River Atlas, 1991), and he privately financed the Truckee-Carson Project in 1888. His project “was one of the most ambitious reclamation efforts of its day and it failed . . . ” (Reisner, 1986). After he became a senator, Newlands, an admirer of John Wesley Powell, became the chief proponent of federal support for reclamation as the only way to stem the state's population decline (Hays, 1959). He drafted the Reclamation Act of 1902, and the Newlands Project was one of the first projects authorized after the passage of the act. The name Newlands was given not because of the “new lands” brought into production but to honor the Senator.

The Truckee-Carson Irrigation District (TCID) is the Bureau of Reclamation 's contract operator for the Newlands Project. Water rights on the project are held by the individual landowners, not TCID. A total of 232,000 acres was originally proposed for the project. The U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) estimated that only 63,100 acres were irrigated in 1985 and that only 56,400 of these have project water rights. Still, the Bureau of Reclamation estimates that the irrigated area may increase because of Indian claims (U.S. DOI, 1986). Among the adverse impacts of the Newlands Project were the drying up of Winnemucca Lake, a national wildlife refuge adjacent to Pyramid Lake, a nearly 80-ft (24-m) drop in Pyramid Lake, and the near extinction of an Indian fishery.

Two Indian reservations assert potentially incompatible claims for the Truckee River. The Pyramid Lake Tribe claims additional flows to improve the quality, quantity, and timing of flows into Pyramid Lake, which in the words of the great western explorer John C. Fremont is “set like a gem in the mountains” (Truckee River Atlas,

1991). On average, 600,000 acre-feet (740,000 ML) flowed into the lake each year before man began to divert and consume the Truckee for irrigated agriculture. Now annual average inflows are reduced by about one-half of historic flows.

The additional flows are needed to allow the cui-ui—a large omnivorous sucker found only in Pyramid Lake, which the tribe considers sacred (Knack and Stewart, 1984)—and the Lahontan cutthroat trout to spawn. The cui-ui are listed as a federal endangered species, and the cutthroat are listed as a threatened species. Typically, the cui-ui migrate upstream from the lake to spawn in the lower Truckee River and then migrate quickly back into the lake. But spawning migration has been blocked or impeded by a delta that has formed in this century as a result of reduced river flow and a consequent drop in Pyramid Lake.

The Fallon Indian Reservation is on the eastern edge of the Newlands Project. This forgotten tribe was promised irrigation water in return for surrendering most of its lands when the Newlands Project was formed. As is often the case with respect to Indian irrigation, the promise went unredeemed for decades (Hurt, 1987). The tribe claims about 18,700 acre-feet (23,100 ML) per year to irrigate 3,100 acres. In 1990 the tribe achieved a considerable measure of justice. As part of the Truckee-Carson-Pyramid Lake Water Settlement Act (P.L. 101-618), a tribal settlement fund was created. Monies may be used to purchase up to 8,453 acre-feet (10,427 ML) per year, as well as for improvement of the existing irrigation system; total tribal water use is limited to 10,568 acre-feet (13,036 ML) per year.

Wetland ecosystem protection has been identified as a major water use in this already stressed area. The Carson River drains into the Lahontan marshes and the Carson sink. Before human settlement, some 85,000 acres of wetlands were sustained by the Carson River, and the Lahontan and Pyramid ecosystems were hydrologically distinct and harmoniously maintained. The development of the Newlands Project created a conflict between the two ecosystems that continues to the present.

In 1905, Derby Dam was constructed on the Truckee near Fernley, and the Truckee Canal diverted more than one-half of the Truckee's flow into the Carson basin. The diversion placed stresses on Pyramid and Winnemucca lakes. Diversions from the Truckee continued relatively unimpaired until the Pyramid Lake Tribe filed suit. In 1966, the Bureau of Reclamation began to adopt criteria to improve the operating efficiency of the project, and a federal court directed the Bureau of Reclamation to develop more stringent criteria for diversions from the Truckee River and operations of the New-

lands Project. Wetland acreage began to diminish in the late 1960s, directly after TCID halted winter diversions solely for power generation. Starting in the 1970s, inflows into the Stillwater National Wildlife Management Area and other wetlands—which are home to bald eagles, feed American white pelicans, and support a wide variety of waterfowl —were diminished and became polluted. Reductions in the district's water conveyance efficiency have resulted in additional decreases. These factors, in conjunction with extended drought and other upstream uses, reduced the marshes to somewhere between 4,000 and 6,000 acres. To relieve this stressed ecosystem, wildlife interests are turning to the market to obtain rights denied them by early adjudications and subsequent reallocations.

Both the Truckee and the Carson are interstate rivers shared by Nevada and California, but there was no formal comprehensive allocation between the two states by Supreme Court decree, compacts, or acts of Congress until 1990. As part of the Truckee-Carson water rights settlement, Congress ratified the long history of judicial decrees, federal agreements, and unapproved compacts to provide a de facto allocation.

THE WATER DELIVERY SYSTEM

Carryover storage and transbasin diversions both play a large role in meeting existing water needs, but water diversions play the most significant role in the Truckee-Carson basins. The Carson River has been dammed only at the lower end to supply the TCID, and above Lahontan Reservoir its flows have great seasonal variation. To guarantee firm yield to the Newlands Project, the Truckee River is diverted to the Carson through the Truckee Canal, which runs from Derby Dam to Lahontan Reservoir. Several upstream reservoirs have been constructed on the Truckee, but there is insufficient carryover storage to provide normal flows during a 2- or 3-year drought cycle. Reno is investigating the extraction of ground water from Nevada's side of the Honey Lake interstate aquifer, about 75 mi north of the area. California ranchers have expressed concerns that the project will dewater the aquifer, but Nevada claims that its safe yield policies will prevent this from happening.

Lake Tahoe, which straddles the California-Nevada border, is both a natural lake of great beauty and a storage reservoir for the Truckee. Lake Tahoe could provide all the carryover storage that the area would need for the long term, but most of the water has been dedicated to in-place, nonconsumptive uses. Tahoe has a total capacity of about 122,160,000 acre-feet (150,685,000 ML), but the lake level is regulated

to fluctuate a maximum of 6 ft, providing only 744,600 acre-feet (918,000 ML) of usable storage capacity. The six other small storage reservoirs constructed on the Truckee and its tributaries have a total capacity of 316,770 acre-feet (390,000 ML). Stampede Reservoir, built in the 1960s, contains the bulk of this capacity with 226,500 acre-feet (279,400 ML).

HOW WATER LAW HAS DEFINED RIGHTS AND CONSTRAINED REALLOCATION IN THE TRUCKEE-CARSON BASINS

The Initial Allocation

The law of prior appropriation has served to create firm property rights in the West's variable streams, and this function has played a dominant role in allocating the waters of these two rivers. Prior appropriation continues to operate as a constraint on reallocation options, but it also serves as a source of marketable rights for new traditional and nontraditional uses. The waters of the Truckee and Carson rivers were appropriated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and this allocation remained relatively constant until the Indians were able to challenge it in the 1970s. Initially, allocation of the Truckee was determined by a series of agreements that fixed the flow rates in the Truckee to maximize the beneficial use of the river for hydroelectric power generation. Subsequently, the available supply of the Truckee River was adjudicated, as was the Carson River. The first dam at the mouth of the Truckee at Lake Tahoe was built in 1870; Truckee River flows, referred to as the Floristan rates, were first established in 1908. In 1915 the Bureau of Reclamation acquired the Lake Tahoe Dam in a consent decree that settled a condemnation suit. This decree gave the United States the right to raise the level of Lake Tahoe and obligated it to maintain the Floristan rates. Adjudication of the Truckee began in 1913, shortly after the California Conservation Commission recommended that the state seek an equitable apportionment of the Truckee and Lake Tahoe.

Truckee River water use is controlled by the Orr Ditch decree (United States of America v. Orr Water Ditch Company, 1944), the establishment of minimum levels for Lake Tahoe, and the Truckee River Agreement of 1935. The decree was not made final until 1944 and was not protected against collateral attack by the Pyramid Lake Tribe until 1983. This decree is administered by a federal water master; his basic task is to maintain a minimum flow at the California-Nevada state line relative to the level of Lake Tahoe.

The Carson River use is allocated by the Alpine decree (United

States v. Alpine Land and Reservoir Co., 1980). It defines the water rights differently. The Orr Ditch decree defines rights as claimed appropriations, whereas the Alpine decree defines rights in terms of maximum consumptive use. Lake Tahoe storage is limited to 744,000 acre-feet (918,000 ML), and withdrawals from the storage pool are controlled by the Truckee River Agreement, in which DOI modified the original Floristan rates to allow additional flood storage. Minimum flows of 400 cubic feet per second (cfs; 11.4 m3/s) are required during the winter months and 500 cfs (14.2 m3/s) during the summer months. Lower winter flows are allowed when the level of the lake is between 6,226.0 and 6,225.25 ft (1,897.68 and 1,897.46 m).

Principal Interests in Water Reallocation Through Transfers

TRIBAL INTERESTS AND ENDANGERED SPECIES IN PYRAMID LAKE

The Orr Ditch decree supported the Newlands Project at the expense of the Pyramid Lake Tribe. In the 1960s the tribe began to challenge the original decree. Although the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately affirmed the finality of the decree, the tribe's objections have rendered the project's rights more uncertain in the past two decades. The Pyramid Lake Tribe's objection to the Orr Ditch decree is that, although it received 14,742 acre-feet (18,180 ML) for irrigation with the first priority, the tribe received no water for maintenance of the lake for traditional subsistence fishing and spiritual culture. Its way of life became imperiled after the Truckee Canal diverted about one-half of the virgin flow of the Truckee River to the Carson basin, causing the lake level to drop precipitously. After a long period of protest with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the tribe turned to litigation to restore the Truckee flows. The tribe pursued three strategies: (1) modify the operation of the Newlands Project, (2) reopen the Orr Ditch decree, and (3) use the Endangered Species Act to control unallocated blocks of water.

The first and third strategies were successful. The Newlands Project controls the major available pool of water open to reallocation. Both the Orr Ditch and the Alpine decrees provide for generous water duties. Allowable deliveries for alfalfa are 4.5 acre-feet (5.5 ML) per year for bench lands and 3.5 acre-feet (4.3 ML) per year for bottom lands. In a major decision, a federal district court held in 1973 that the tribe was owed a trust duty to maintain the level of the lake and ordered DOI to modify the operation of the Newlands Project (Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe of Indians v. Morton, 1973).

In response to this decision, DOI has issued progressively more stringent sets of Operating Criteria and Procedures (OCAP) for the Newlands Project, which assume that annual diversions from all sources to satisfy project irrigation rights will be reduced from 370,000 to 320,000 acre-feet (456,400 to 394,720 ML). The OCAP “are predicated on water being used on . . . water righted land in a similar manner as in the past with the project operating at reasonable efficiency ” by reducing seepage, evaporation, and spill losses. Basically, the OCAP try to ensure that headgate water deliveries match court-decreed water duties; they establish efficiency targets for the project' s distribution system and maximum allowable diversion that reduces annual diversions as the project's physical efficiency increases. If the Newlands Project's actual delivery efficiency exceeds the target efficiency for a water year, the district will receive a Lahontan storage credit for the Carson portion of two-thirds of the saved water. The net results are that more water should flow into Pyramid Lake and less into the Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge Area and that the Fallon Reservation still has an unsatisfied irrigation right.

The reductions required by OCAP only slightly ameliorate the drop of Pyramid Lake level. The tribe tried to reopen the Orr Ditch decree on the grounds that DOI's representation of both the tribe and the Newlands Project landowners in the adjudication constituted a conflict of interest. The U.S. Supreme Court held that the tribe had been adequately represented and thus the decree was final (Nevada v. United States, 1983). The tribe continues to object to other aspects of the Orr Ditch and Alpine decrees with limited success. For example, the tribe raised a public interest objection to the TCID's transfers of water from unirrigated lands with water rights to irrigated lands without water rights, but the Supreme Court dismissed it as simply a collateral attack on the Orr Ditch decree. The eligibility of lands to receive project water is still being litigated (United States v. Alpine Land and Reservoir Co., 1989).

Despite these setbacks, the tribe has been able to assert its traditional water uses to achieve results through the Endangered Species Act. After the cui-ui was listed as endangered and the Lahontan cutthroat as threatened, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that Stampede Reservoir, built in the 1960s to supplement Reno's water supply, had to be managed to maintain the fish species instead of for municipal and industrial uses. Stampede storage can be released to TCID as part of the reservoir credit established by the yearly OCAP. TCID is entitled to a storage credit for the difference between the actual amount saved and the target amount. Further litigation has established that DOI need not carry over the credit from year to year (Pyramid Lake Tribe of Indians v. Hodel, 1989).

This decision has given the Pyramid Lake Tribe great leverage with upstream users, to complement the leverage that the earlier decision gave it with the Newlands Project. Reno-Sparks was unable to use Stampede Reservoir as a drought reserve and was forced to negotiate a legislative settlement. Under the Truckee-Carson-Pyramid Lake Water Settlement Act (P.L. 101-618), the Pyramid Lake Tribe, Reno-Sparks, the state of Nevada, and the United States reached a preliminary settlement agreement that requires the Secretary of the Interior to operate the Truckee River reservoirs to implement an earlier agreement among the parties. The reservoirs will continue to be used to maintain spawning flows, but Reno-Sparks obtained the right to use 7,500 acre-feet (9,250 ML) of Stampede water in “worse than critical drought conditions. ”

URBAN GROWTH IN THE TRUCKEE MEADOWS AREA

Litigation has enabled the Pyramid Lake Tribe to influence water use throughout the Truckee-Carson system. This creates substantial problems for water suppliers and developers in the Truckee meadows area; they have neither secure access to federal reservoirs nor clear access to alternative supplies. Interstate ground water use remains uncertain. To accommodate the continued unchecked growth in the Reno-Sparks area, water suppliers and developers have had to acquire existing irrigation rights. As a result of tribal pressure, the state legislature reversed its historic no-water-metering policy, but the community has yet to vote on the issue. The price of water rights has risen over the past 15 years from less than $750 per acre-foot to between $2,500 and $3,000 per acre-foot (less than $608 per ML to between $2,030 and $2,430 per ML).

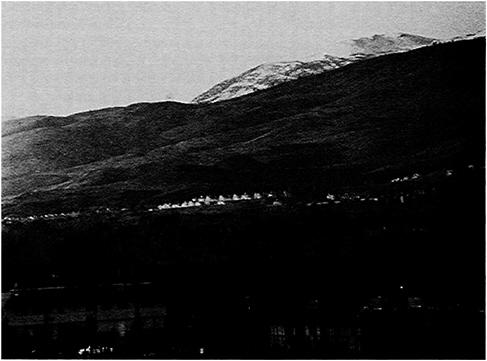

Most of the existing water rights have now been acquired by WESTPAC, the water supply division of Sierra Pacific Power. The major potential third party effects of these reallocations will be on downstream users. Downstream water rights holders are entitled to return flows. Water used by Reno historically has been returned to the stream as treated effluent. The problem is that these discharges currently violate the Clean Water Act, and Reno and Sparks are seriously considering land disposal as a treatment alternative. This, if it occurs, may reduce return flows. All western states have struggled with how to allocate the entitlements to treated sewage. The Arizona Supreme Court, for example, has held that sewage effluent is waste-water; thus a city has no obligation to downstream users to continue to discharge it or to provide substitute supplies. The Nevada state engineer has taken the opposite position. More generally, the third

Urbanization is increasing in the arid Truckee-Carson basin, and new development such as these homes in Reno, Nevada, puts added pressure on the region's limited water resources. The area's transition away from an agricultural economy mirrors land use changes in many areas of the West. CREDIT: Todd Sargent, University of Arizona.

party and ecosystem effects of the use of treated sewage are not well understood.

Facilitated by the pressure and interest of Nevada's U.S. Senator Frank Reid, in 1990 the major parties in the basins negotiated a settlement to the ongoing dispute. Reno-Sparks may switch to land disposal of sewage to avoid the higher costs of building a treatment plant to comply with Clean Water Act standards; the Pyramid Lake Tribe wants an assured supply of more and cleaner water to maintain and raise the lake level; and federal and state officials have shown a willingness to consider the use of treated effluent for the Fernley wetlands. This solution may require the purchase of additional irrigation rights as replacement water for the tribe. The Newlands Project is the most likely source because prices are much lower than in the Truckee meadows. The parties are considering piping the effluent to a wetland site north of Fernley or to Dodge Flat on the Pyramid Lake

Indian Reservation. It will be spread to ensure rapid infiltration. Whether this will work and will satisfy tribal concerns remains unclear. The Dodge Flat alternative would have several advantages that could benefit Pyramid Lake fish species: water would remain within the Truckee basin, pumping could be timed to meet seasonal water needs in the river, and water quality would improve.

Sierra Pacific Power and the Pyramid Lake Tribe also negotiated a preliminary settlement agreement that was included in the final congressional legislation in 1990. With respect to the Truckee River, the agreement allows the management of Stampede Reservoir for spring spawning flows for the cui-ui and for drought reserve storage for the benefit of Reno-Sparks. Downstream users will be protected, although continued discharges from the Reno-Sparks sewage treatment plant may be necessary to firm up downstream rights. The tribe's role was twofold: to bring the pressure needed to provoke a settlement and to take the initiative to lead the parties to optimal solutions.

WETLAND ECOSYSTEM MAINTENANCE IN THE LAHONTAN VALLEY

Fish and wildlife protection is difficult to achieve in the area because the history of diversions has led to a situation where wetland ecosystem maintenance is last on the list of protected uses. Upstream consumptive uses have diminished flows into Stillwater National Wildlife Management Area, and efforts to restore the levels of Pyramid Lake have further limited flows to Stillwater. The wetlands have shrunk drastically because of a recent drought and continued upstream diversions. If this wetland area is to be preserved as a wildlife sanctuary, it will require more and better-quality water. Approximately 50,000 acre-feet (62,000 ML) of acquired water rights are needed to support a permanent 25,000-acre marsh. Furthermore, this must be “prime water ” (i.e., nondrain water) in addition to the drain water that already is being received. This water will not come from the Truckee River; such reallocation is precluded because of the rights of the Pyramid Lake Tribe under Indian law and because of the Endangered Species Act and the demands of the Reno-Sparks area. Therefore the water must come from the Newlands Project. Since the Pyramid Lake Tribe is the beneficiary of all savings achieved through the OCAP, rights for the Stillwater refuge must come from reallocation of the Carson basin supplies.

The OCAP seek to serve all existing rights holders through more efficient operation of the project. Since 1987 the Environmental De-

fense Fund, consistent with its efforts to solve water problems through market transfers of water, has urged the use of voluntary water rights acquisitions to provide the necessary water for the management area. Environmental interests are proceeding on the assumption that irrigation use must be reduced by 50,000 acre-feet (61,680 ML) to restore the area. This water could come from increasing conveyance efficiencies over and above OCAP target levels or by retiring approximately 23 percent of the existing irrigated land (Yardas, 1987). In December 1989 The Nature Conservancy paid $135,000 to purchase water rights (about 400 acre-feet, or 490 ML) from 150 acres of marginal farmland. Under the Truckee-Carson-Pyramid Lake Water Settlement Act (P.L. 101-618), water rights may be purchased from willing sellers, but the Secretary of the Interior may target “purchases in areas deemed by the Secretary to be the most beneficial” for the purchase program. By the end of 1993 the Secretary of the Interior must conduct a study of the social, economic, and environmental effects of the water rights purchase program.

RECENT AND PLANNED TRANSFERS

Nontraditional water-using interests are behind three of the four major water transfers occurring in the Truckee-Carson basins. The major water transfers taking place in this basin are as follows:

-

Newlands Project agricultural water to Stillwater National Wildlife Management Area for wetland maintenance. This is a private transaction and produces satisfaction for most parties with no significant external effects.

-

Newlands Project agricultural water to the Truckee meadows for urban use. This is a voluntary transfer involving changes in ownership use within the basin. Some potential externalities from disposal of municipal effluent on land versus other direct uses are involved.

-

Newlands Project agricultural water to Pyramid Lake Tribe for cui-ui fish species protection. This reallocation involved an involuntary transfer effected through a change in system operation by the Bureau of Reclamation. This then led to “voluntary” increases of on-farm irrigation efficiency. This reallocation was forced by legal and political pressures to mitigate prior inequities. Had externalities been greater, some forms of compensation may have been required.

-

Reno urban water from Stampede Reservoir storage to Pyramid Lake for cui-ui species protection. This involuntary transfer was brought about by litigation resulting in a change in use of the water stored in Stampede Reservoir (originally proposed for provid-

-

ing drought contingency for the municipal users) and dedicating this water for delivery downstream during the spawning season of the cui-ui. This involved fundamental conflicts of social values and interests and was resolvable only through the courts in the absence of a market of willing sellers.

Voluntary water transfers seem an attractive way to address the third party effects of past water allocation choices because they can provide an accurate measure of the value of water and do not constitute a taking of existing rights. As clean water reaches the refuge through this process, the transfers represent an efficient and fair allocation of resources. This is especially true for marginal agricultural areas as in the Newlands Project. Crop production has not been central to the economic prosperity of the Fallon area because of the expansion of a naval air station. However, the solution to a complex ecological and social problem such as this will not be left to an unregulated market. To balance efficiency, equity, environmental, and local economic concerns, the water transfers must be consistent with criteria that seek to achieve these objectives, and the transfers must be monitored carefully.

There are two major problems with the acquisition alternative, although they do not arise in every transfer. When a buyer has identified a willing seller, it is assumed that the seller's water rights meet the buyer's needs. This assumption cannot be made when there are one buyer and a large number of willing sellers with rights of unequal quality. Water rights must be screened for eligibility.

The two problems center on eligibility and the assurance of “wet water.” First, there are serious issues of implementation. Not every water right should be classified as eligible for acquisition. In the Newlands Project, not all lands have project water rights, and many rights are paper rights (i.e., the right is based on decreed amounts rather than actual beneficial use). Second, a water right that is not put to beneficial use may be lost by either forfeiture or abandonment. In Nevada, a pre-1913 right can be terminated only through abandonment, whereas a post-1913 right may be terminated more easily through forfeiture (In re Manse Spring and Its Tributaries, 1940). Because most water rights in Nevada predate 1913, they are difficult to terminate. Thus there is a need to ensure that the water rights that are purchased in fact represent “wet water” that has been put to active use for some period before the transfer.

Market price provides an indicator of the value of water, but it is not always the most reliable indicator. A variety of intangible or unquantified social and environmental values may be associated with

the importance that an entire community attaches to a stable pattern of water allocation. There may be a community interest in the status quo that is not reflected in individual bargains. And even though the individual farmers, most of whom do not earn their livelihood exclusively from the irrigated land, may be satisfied with the compensation, such marketplace transfers do not prevent the character of the local area from changing. Changes may cause economic dislocations among those who depend on the agricultural base of the area. Some of these effects can be mitigated by social regulation of the market process. For instance, transfer deliveries can be delayed to allow suitable replacement crops; yearly and total ceilings can be placed on the amount of water that may be acquired for a given use; and irrigated parcels can be selected for acquisition with an eye toward minimum disruption of the area. Community participation mechanisms can increase the legitimacy of transfers.

Transfers began occurring in late 1989. The federal government has already appropriated money for water rights acquisition for Stillwater refuge. The Nature Conservancy purchased the permanent water rights on 150 acres from a farmer serviced by the TCID for conversion to instream flows. Wildlife management is a beneficial use under Nevada law (State v. Morros, 1988), and after a negotiation with the district, the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the state engineer approved the permanent transfer of 162 acre-feet (200 ML) of these rights to the Stillwater National Wildlife Management Area. Nevada law allows the transfer of water from irrigation districts if the proposed change of use does not adversely affect the cost of water to other water rights holders (Nevada Revised Statutes § 533.370). The TCID's possible objections were allayed by The Nature Conservancy 's promise, which has now been assumed by the federal government, to assume the farmer's 40-year repayment obligation, and the tribe was satisfied by assurances that Truckee flows would not be altered. Also, 27 acre-feet (33 ML) were purchased by the Nevada Waterfowl Association and transferred under a Nevada statute that allows 1-year transfers on an expedited basis (Nevada Revised Statutes § 533.345). There is still a reluctance on the part of some farmers to sell water rights, but the price incentive is a powerful way to overcome resistance by creating willing sellers.

CONCLUSIONS

The Truckee-Carson area provides a graphic example of the complexities of water allocation in the West. This hydrologic system clear-

ly illustrates the conflicts that can occur among urban, agricultural, environmental, and tribal interests, and it raises issues about federal water project management, endangered species, wetland protection, and water quality degradation. The many pressures for reallocation of water highlight the need for institutions and decisionmaking processes capable of responding efficiently and equitably to accommodate new and traditional water values in the region.

Over the past decade, various judicial decisions, administrative actions, and negotiated settlements have resolved some of the basin 's allocation problems, but great controversy continues over many issues. The most promising solution resulting from recent negotiations is the passage of federal legislation authorizing and appropriating funds for voluntary acquisition of water from willing sellers in the Newlands Project for the benefit of the Stillwater National Wildlife Management Area. Although major issues regarding the nature and quantification of water rights “appropriate for transfer” still exist, some precedent-setting transfers have occurred and are gaining support among a wide array of interest groups and government agencies.

Substantial additional progress toward meeting both environmental restoration and tribal equity goals could be achieved, while protecting affected agricultural communities, if water rights status could be ascertained quickly and finally. With sufficient federal, state, and private funding, all parties to the basin conflicts could see their interests protected—provided they continue to bargain in good faith, respect the interests of their adversaries, adopt an integrated water management perspective, and diligently apply water conservation measures to consumptive uses.

The efforts under way to balance existing and new uses of water through negotiation and market transfers were stimulated by judicial decisions that reduced preexisting entitlements. The net effect of the court 's findings in favor of the tribe's effort to preserve its fishery was to deprive Reno of a block of reservoir storage that it thought was reserved for future growth and droughts and to force the TCID to operate the Newlands Projects more efficiently. Once the tribe was so empowered, the Bureau of Reclamation had to adjust its management of Stampede Reservoir and delivery of water to the TCID. The tribe subsequently was included in broader negotiations about the Truckee's future.

Many of the issues illustrated in this case—interstate allocations, water supply agreements, wetland protection, endangered species enhancement, water rights purchase, Newlands Project operation, Fallon Tribe claims settlement—are addressed in the 1990 settlement act. However, many provisions of the bill must still wait for completion

of the National Environmental Policy Act process. The preliminary settlement agreement is contingent upon development of an operating agreement for upper Truckee basin reservoirs. A new management plan will also consider instream flows to protect and enhance the resident fishery. Thus the tribe's entitlement to a block of storage water and the ongoing transfer of water rights from agriculture to urban and environmental uses are forcing the Bureau of Reclamation to seek a river basin management solution to the disputes. A dominant factor in the development of OCAP was the Endangered Species Act—final OCAP were required to pass the test of “not likely to jeopardize” the cui-ui and Lahontan cutthroat trout. The Bureau of Reclamation has endorsed and worked diligently to achieve negotiated and legislated solutions to the water disputes in the Truckee-Carson basin. Throughout the consultation process, the Bureau of Reclamation worked with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to develop computer models that could assess the relative impacts of various water management (storage and delivery) plans on cui-ui population survival. This cooperation continues and provides the basis for the yearly OCAP.

As part of its recent shift toward a management emphasis in its mission, the Bureau of Reclamation will need to recognize that there is a disparity between regulations governing water management and historical practices; the agency that controls the water controls other resources as well and has the responsibility and authority to protect social and environmental values (in that the federal government owns the storage and distribution facilities but not the water and so cannot market the supply). To function as a water resource management agency, the bureau must view itself as such and truly espouse a “total water management philosophy ” among multiple users, where project operating efficiency and local drain-water quality will be primary parameters for establishing basin management criteria and seasonal delivery patterns.

REFERENCES

Athearn, T. G. 1986. The Mythic West in Twentieth-Century America. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

Hays, S. P. 1959. P. 11 in Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement 1890-1920. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Hurt, R. D. 1987. Indian Agriculture in America: Prehistory to the Present. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

In re Manse Spring and Its Tributaries, 108 P.2d 311, Nevada ( 1940).

Knack, M., and O. Stewart. 1984. As Long as the River Shall Run: An Ethnohistory of the Pyramid Lake Reservation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nevada v. United States, 463 U.S. 110 ( 1983).

Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe of Indians v. Morton, 354 F. Supp. 252, D.D.C. ( 1973).

Pyramid Lake Tribe of Indians v. Hodel, 882 F.2d 364, 9th Cir. ( 1989).

Reisner, M. 1986. P. 116 in Cadillac Desert. New York: Viking Penguin Press.

State v. Morros, 776 P.2d 262, Nevada ( 1988).

Truckee River Atlas. 1991. State of California, Department of Water Resources. Sacramento.

U.S. Department of the Interior (U.S. DOI), Bureau of Reclamation . 1986. Pp. 68-69 in Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Newlands Project Proposed Operating Criteria and Procedures. Sacramento: URS Corporation.

United States v. Alpine Land and Reservoir Co., Nos. 87-1746; 87-1747, U.S.D.C. Nev. ( 1980, aff'd.).

United States v. Alpine Land and Reservoir Co., 878 F.2d 1217, 9th Cir. ( 1989).

United States of America v. Orr Water Ditch Company, Final Decree ( 1944).

Yardas, D. 1987. Birds Versus Fish: An Environmental Perspective on Water Resource Conflicts in the Truckee-Carson River Basins. Comments prepared for the Water in Balance Forum, Reno, Nev.