3

Professionalism in Education

We need to be sure that our educational models and systems don’t discourage collaborative interactions but in fact become the supporting mechanisms for going forward.

—Charlotte Exner, Association of Schools of Allied Health Professions

TEACHING PROFESSIONALISM

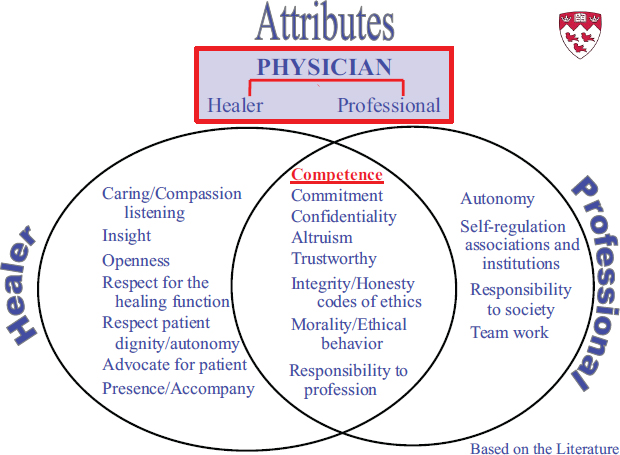

In their presentation on the social contract for health professions and health professional education, Richard Cruess and Sylvia Cruess from the Centre for Medical Education at McGill University in Canada suggested that the concept of a social contract helps in teaching and learning about professionalism. When they teach, they emphasize that health care professionals are both healers and professionals, but separating the roles into distinct categories makes the concepts easier to explain to students.

The left side of Figure 3-1 shows attributes of a healer, who is caring and compassionate, insightful about the patient’s and the healer’s own feelings, open to different cultures, aware of the healer’s role in the healing process, and respectful of the patient’s dignity and autonomy. Sylvia Cruess then noted that the right side of the figure shows attributes that are not found in the Hippocratic Oath and are not in the healer tradition. These attributes define degrees of professional autonomy that allow health professionals to set their own rules and regulations for entry into the profession as well as the exit from it.

The role of the healer and the professional can at times be at odds with

FIGURE 3-1 Healer and professional attributes.

SOURCE: Cruess and Cruess, 2013.

each other, but according to Sylvia Cruess, they are also linked by the codes of ethics that describe the behavior of both the healer and the professional. In the middle of Figure 3-1 is a list of shared attributes, which include a commitment to help the patient, confidentiality, altruism to put the patient’s needs above health professional’s own, and trustworthiness, meaning that the health professional possesses integrity and honesty.

By learning about professionalism and the social contract, said Sylvia Cruess, students better understand what professionalism is and what their obligations as health professionals will be to society. Students develop their professional identity at this time, and teaching professionalism creates an opportunity to shape their views by looking at where the health professions have failed society. Possibly health professionals are not as altruistic as society expects while they balance lifestyle with altruism and responsibility to society with financial gain. Also, not addressing the distribution of resources among the population may be judged negatively by society, as some may view this as a lack of social justice.

Richard Cruess noted that negotiations are needed between society and health professionals (with regard to issues such as conflicts of inter-

est and financial gains) to address the external stresses that society uses to judge health professionals. But this requires a single coordinated voice and the recognition that there are multiple stakeholders, including some with commercial interests. It also requires somebody with whom to negotiate and a neutral space—typically set up by government—where parties can come together. In this regard, society may determine the nature of the social contract, and therefore professionalism, but because society needs healers, they will need to reach an agreement with the health professionals that preserves trust and satisfies both sides.

INNOVATIONS IN TEACHING ABOUT PROFESSIONALISM AND PROFESSIONAL NORMS

Workshop moderator Charlotte Exner represented the Association of Schools of Allied Health Professions as part of its Interprofessional Education Task Force. She noted that in higher education, a rapid and intense transformation is happening. The use of technology and other teaching and learning methods is forcing faculty to consider new educational models. And there is the driving force of students who learn in different ways and expect their academic programs to reflect the changes taking place in society. For example, there is momentum toward the flattening of hierarchies in the workplace to adopt more collaborative environments. Exner described how greater access to information has altered education around the world through massive open online courses (MOOCs) and has changed the discourse between health professionals and patients, who now have online sources of information readily available to them. Educators can pick up on the momentum to be sure that health professional educational models and systems do not discourage that kind of interaction but in fact support it going forward.

Teaching Interprofessional Professionalism from Psychology

Susan McDaniel from the University of Rochester Medical Center presented an educational model that encourages the sort of interaction recognized by Exner. McDaniel studies, writes, and teaches physicians, psychologists, and other clinicians about the bio-psychosocial approach to medicine, professionalism, and team-based care. She asked, “How do we find new ways to teach about an approach to creating and carrying out a shared social contract that ensures multiple health disciplines working in concert and worthy of the trust of patients and the public?”

According to McDaniel, the response lies in the methods used to teach health care team competencies and begins by selecting students and educators whose values align with those of transdisciplinary professionalism.

This might involve establishing search and admissions committees that include members from other health professions and patients who can identify candidates who possess the attributes and behaviors inherent in professionalism. It also involves communication. McDaniel views communication as one of the central aspects of professionalism; how she incorporates this into her teaching is described in detail in her paper in Part II of this report. Briefly stated, McDaniel uses the child’s game of “telephone” to initiate a large-group discussion about the problems with multiple communications and how emotion affects them. She developed a number of other programs that similarly work toward improving communication between professions. One program in particular addresses communication skills and disruption of the hidden curriculum with regard to professionalism. This program, called the Patient- and Family-Centered Care Physician Coaching Program, builds on the concept of feedback that is focused on patient complaints and on the patient experience. It began with the endorsement by the medical center leadership of a set of values that spell out ICARE: Integrity, Compassion, Accountability, Respect, and Excellence. Each profession then developed its own most important ICARE job behaviors that were then compiled into three primary behaviors associated with improved quality in patient satisfaction.

In response to a question raised about communication, McDaniel commented that psychologists on teams often notice when people do not communicate well with each other. Individual professions may use profession-specific terms to convey the need to put the patient at the center of care while working collaboratively. In her opinion, this is not very different from family therapy. Such therapy opens communication, as does interprofessional training that McDaniel strongly advocates. Training students through projects that require different disciplines to work together toward a common goal—for example, a quality improvement or community health project—is an excellent way for different disciplines to learn from and with each other. In looking at the broader picture of the role professional societies might play to advance better communication in support of a social contract, McDaniel believes this interprofessional training is key. Professional associations could influence their members and trainees through education, leadership, inspiration, and projects. In this way, associations could motivate their leaders to come together in agreement and could influence their members to join with other professions in forming a social contract with society.

Professionalism in Public Health Education

Jacquelyn Slomka from the School of Nursing at Case Western Reserve University discussed incorporating the teaching of professionalism into public health courses. She first said that public health is not so much a dis-

cipline as a concept. And as a concept, public health embraces health care delivery, disease prevention, health promotion, and health policy. In the United States, she said, she sees what is sometimes called a medicine–public health divide, which does not exist in other countries. She noted that after the anthrax attacks that followed September 11, 2001, there was a renewed interest in public health and community-level responses, and, at the same time, a renewed attention to public health ethics and professionalism.

The Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) developed professionalism competencies for the master of public health degree that predates the September 11 attacks. According to ASPPH, students in this degree program are expected to “promote high standards of personal and organizational integrity, compassion, honesty, and respect for all people.” They are also expected to “distinguish between population and individual ethical considerations in relation to the benefits, costs, and burdens of public health program” (ASPPH, 2006). At the more advanced level, the doctorate of public health degree, students are expected to be able to manage potential conflicts of interest (ASPPH, 2009).

These competencies, described more fully in Slomka’s paper in Part II of this report, can be used as standards for teaching professionalism. Slomka uses them as the backdrop for conveying the differences and similarities between population and individual ethical decision making. She begins by looking at the patient–healer relationship. Patients in the clinical setting are sick and therefore very vulnerable, whereas in public health settings, patients tend to be more ambulatory and are often part of a wider community or population. These different environments alter the responsibilities of professionals, between those to individuals and to the community, ultimately influencing the structure of the social contract.

One difference between professionals relates to language. Clinically based health professions derive their concepts primarily from their use of biomedical thinking, whereas in public health the language and concepts are derived from ethical practice, human rights, and social justice.

For similarities, Slomka highlights those values shared between the clinical professions and public health. These values may involve principles such as justice and respect. There are also shared professionalism processes in that both public health and clinically based professions have to weigh the burdens and benefits in deciding the right course of action in any particular situation.

In discussing teaching strategies, Slomka combines didactic with experiential learning. She requires students to observe health care teams at work to identify the interprofessional values the students discussed in class. The experiences include attending multiple interdisciplinary rounds in an intensive care unit, observing a series of institutional ethics committee meetings, or viewing internal review board sessions where research proposals are

discussed that often have both clinical and public health implications. In this way, students gain a better understanding of how various professionals working together can effectively consider and make decisions.

Slomka also makes full use of literature and film to educate students about public health professionalism. In one example, students read the popular short story “The Use of Force” by William Carlos Williams. The story is about a physician who, during the Great Depression, is trying to examine the throat of an uncooperative sick child whom he believes may have diphtheria and could be the start of an epidemic. Slomka uses this story to address a situation that not only involves ethical decision making with individuals but also has public health implications. She believes that literature and film can educate students not only about compassion but also about their power to influence health care policy to improve community conditions.

Teaching Professionalism at a Business School

Workshop speaker Patricia Werhane is from the Institute of Business and Professional Ethics at DePaul University. Her work in health care focuses on ethical issues in health care organizations. She discussed managerial professionalism, lessons learned, and how professionalism is taught in business schools. Business schools primarily teach skills, according to Werhane, in contrast to teaching intellectual training. Some voluntary codes have been adopted, but there are no general codes, and there are no professional organizations, no prioritization of professionalism, and no enforcement mechanisms. Other than the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission—whose mission is to “protect investors, maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets, and facilitate capital formation”—there are no stopping rules1 (U.S. Securites and Exchange Commission, 2013).

This managerial method of teaching professionalism has led to what Werhane called a “silo mentality,” as was described earlier by McDaniel. It occurs within business education as well as in training, so managers do not develop an awareness of ethical issues in the nature of their work. Managers believe that ethics are the responsibility of others. The result is that business schools create good managers but not good leaders, what Rakesh Khurana called “hired hands” in his book about the social transformation of American business schools and the unfulfilled promise of management as a profession (Khurana, 2010).

For a positive perspective, Werhane pointed to examples of systems thinking in global commerce. She cited Paul Plsek’s work on the health care system as a complex adaptive system (CAS). Plsek and colleagues define

________________

1 In this context, stopping rules are pre-established conditions that would dictate termination of an experiment or activity.

the CAS as “a collection of individual agents who have the freedom to act in ways that are not always totally predictable, and whose actions are interconnected such that one agent’s actions change the context for other agents” (Zimmerman et al., 1998).

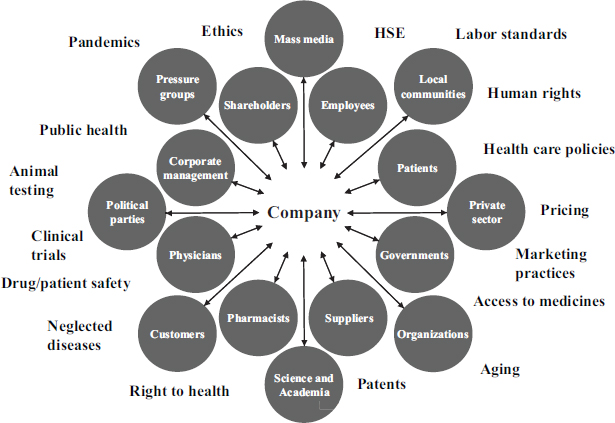

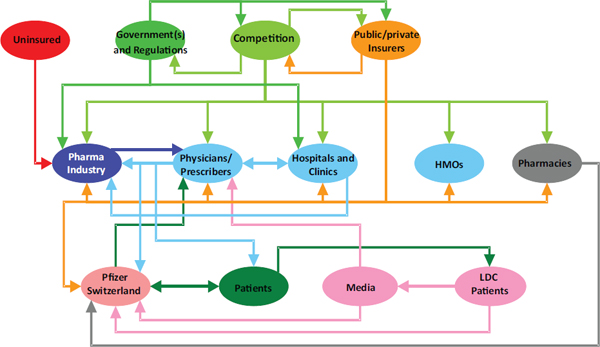

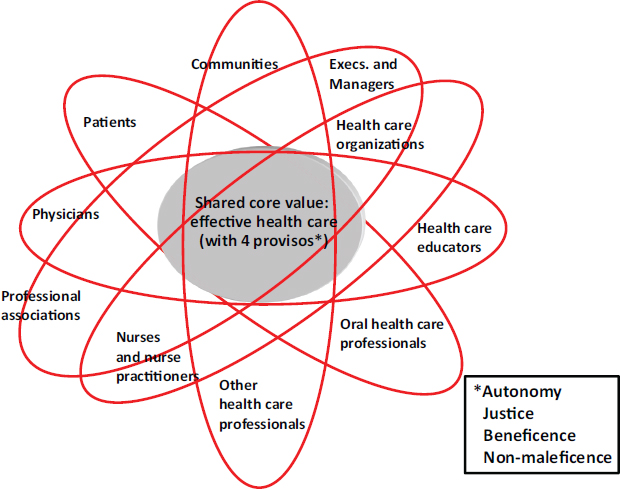

According to Werhane, a number of companies see themselves as integrated within their interdependent health care system. One example is Novartis, the third-largest pharmaceutical company. Novartis embraces the systems stakeholder model, with Novartis at the center of the stakeholders (see Figure 3-2 for an example of this type of model). In contrast, Pfizer Switzerland adopted a systems model view of the health care world, with bidirectional inputs and outputs from the various stakeholders, including their company (see Figure 3-3).

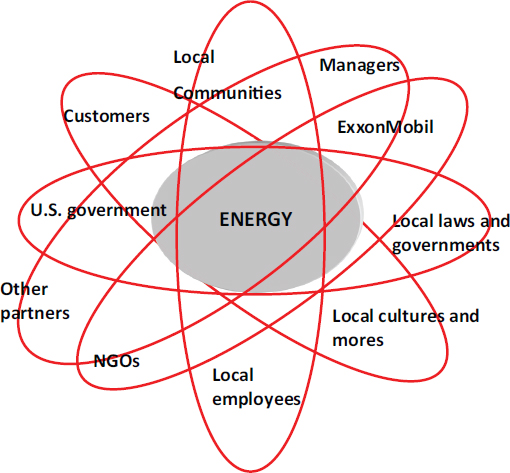

Werhane highlighted ExxonMobil (see Figure 3-4) as an example of the systems-alliance model. This company places energy, which is its primary product, in the middle and with all partners in orbit around the core energy business. It does not put itself in the middle. It puts what it does in the middle, which Werhane finds quite interesting.

The systems approach model becomes very complex and chaotic when it is translated from business to health. Werhane drew on the ExxonMobil

FIGURE 3-2 A systems stakeholder model.

NOTE: HSE = health, safety, and environment.

SOURCE: Adapted from Werhane, 2013.

FIGURE 3-3 A systems model.

NOTE: HMOs = health maintenance organizations; LDC = low-density cells.

SOURCE: Werhane, 2013.

FIGURE 3-4 A systems-alliance model for ExxonMobil.

NOTE: NGOs = nongovernmental organizations.

SOURCE: Werhane, 2013.

example to identify a transdisciplinary approach that establishes an alliance among the health professionals that is tied together by a shared core value of effective health care (see Figure 3-5). For this to be an effective discussion, however, the health professions need a common language that all understand and use to communicate.

To explain her thinking, Werhane referred to the work of a commission in World War II that brought together a wide array of thinkers from various professional backgrounds and sectors. The commission involved engineers, philosophers, social workers, social scientists, and government officials in the development of radar in order to win the war. The commission quickly realized that each professional representative used a jargon unique to his or her profession. They needed to develop a mutually shared language, and by creating a language, they tagged “Creole,” the commission was able to work effectively together.

Developing “a Creole” that all health professions can understand is what Werhane believes is needed to create transdisciplinary professionalism. In describing how she teaches this concept, Werhane echoed educational

FIGURE 3-5 Shared core values model for effective health care.

SOURCE: Werhane, 2013.

tactics described by McDaniel and Slomka. These tactics include using short case studies and having learners from different health professions share different perspectives. She encourages active listening in order to translate the different perspectives and come to consensus around values. Once the values are established, Werhane believes, then the different professions or sectors can prioritize these values based on the needs of their individual professions. One lesson Werhane teaches her international students is that disagreement on the prioritization of values is acceptable as long as there is mutual respect among groups.

INNOVATIONS IN TEACHING LEADERSHIP THROUGH PROFESSIONALISM

Members of the Global Forum who represent schools and institutions in Canada, India, and South Africa have undertaken the development of interprofessional training activities and curricula in the area of leadership for health professionals. Representatives of the Collaboratives participated

Pictured from left to right: Emmanuelle Careau, Canadian country collaborative; Maria Tassone, Canadian country collaborative; Himanshu Negandhi, Indian country collaborative; Sanjay Zodpey, Indian country collaborative; Marietjie de Villiers, South African country collaborative; Sarita Verma, Canadian country collaborative; and (not seen) Juanita Bezuidenhout, South African country collaborative.

in the workshop to educate and to learn from colleagues about curriculum development. In her remarks, Marietjie de Villiers from the South African Collaborative referred to the Cruesses’ slide on physician attributes—discussed previously in the report—that parallel desired qualities of a strong leader. The notion that professionalism equals leadership provided her with a deeper understanding of what it means to be an interprofessional leader. To be a good leader, one must also know how to follow. For her, one of the keys to successful interprofessional professionalism and leadership is knowing how to be a humble follower.

South African Collaborative

Juanita Bezuidenhout, also from the South African Collaborative, explained the goal of their project, which is to determine the relevant competencies required for transformational and shared leadership in the context of health teams in South Africa. To start the process, Bezuidenhout interviewed leadership and faculty at Stellenbosch University. She then identified a set of leadership qualities or attributes that provide an enabling environment. These include having a strong value system, building relationships, being able to create meaning, being strategic thinkers, and being able to communicate. She also described a desire for leaders to collaborate and to function as role models through structured mentorship programs designed to develop the next generation of leaders.

Indian Collaborative

Like the South African Collaborative, the Indian Collaborative is undertaking the design and development of an interdisciplinary leadership competency model for training as part of the curriculum for medicine, nursing, and public health students and as a component of in-service professional education in India. Forum member Sanjay Zodpey presented their progress. The Indian Collaborative began by reviewing the various professional curricula and found them to be content specific, as well as lacking in cross-professional competencies such as leadership. Because interprofessional education was lacking, representatives from the health professions partnered to come up with shared and collaborative leadership competencies.

After reviewing the competencies within the wider health systems context and speaking with key stakeholders from education, government, and other professions, the collaborative then developed a training model that was pilot tested. This 3-day interprofessional in-service training program is for medicine, nursing, and public health students and professionals. Members of their collaborative would like to see their training model incorporated into the curriculum for medical, nursing, and public health education as well as into several initiatives, like the National Health Mission Initiative in India, as in-services for professionals.

Himanshu Negandhi, Assistant Professor at the Indian Institute of Public Health–Delhi, described a need for the leadership training and education that Zodpey described. India recently initiated the National Rural Health Mission, which provides an institutional framework for strengthening primary health care. It resulted in a new cadre of public health professionals at the primary level who are overseen by a public health manager. These people implement the health system’s national programs and serve as a liaison between the government and the local health needs of the people. They are expected to fulfill the roles and responsibilities of being a public health manager, which requires strong leadership skills. Without the training developed by the Indian Collaborative, however, there would be no formal process for gaining the leadership skills that were discussed by de Villiers and shown in the Cruesses’ Venn diagram.

Canadian Collaborative

Maria Tassone and Emmanuelle Careau spoke for the Canadian Collaborative, which is focusing its work on developing systems leaders to enact socially accountable change within their communities. In her remarks, Tassone referred to the previous discussions at the workshop on the social contract. The social contract empowers people to influence change, she

said, which is the root of their work around the development of a collaborative leadership program.

Careau described the extensive systematic literature review of existing curricula on collaborative leadership conducted by the Canadian Collaborative in an effort to understand which competencies are addressed in those curricula, how they are addressed, and what the impacts of those curricula are on learners and the health care systems. The results showed that few educational programs address collaborative leadership. Most of them focus on developing knowledge skills and behaviors of individual leaders. Most of these programs are taught within one discipline, and only 10 percent of the peer-reviewed articles present truly interprofessional education initiatives.

Concerning evaluation, added Careau, most of the programs measure the short-term impacts through the learner’s knowledge, skills, and behavior. Few of the programs on collaborative leadership measured the impacts on systems change or on patient and family outcomes. And none of the programs used learner methods and tools to measure their own impacts as leaders once the program was completed.

Following their literature review, Tassone reported that the collaborative conducted interviews of roughly 35 international thought leaders in health professions education in government, in business, in health care, and across the student body. Many of the characteristics of collaborative leaders had been previously identified by other speakers. The set of practices that collaborative leaders draw on is different from current leadership curricula in health care programs, however. These practices include

- co-creating a shared vision with communities as opposed to selling a vision that comes from a charismatic leader;

- using group process to draw on diverse and multiple perspectives, actively listening to those diverse opinions as formal leaders while suspending their own assumptions and beliefs;

- engaging in ongoing self-awareness and self-reflection; and

- dismantling traditional silos in order to connect groups that have not been connected before.

In Tassone’s view, collaborative leadership as a philosophy and as a leadership program offers the promise and opportunity to root the work of the health professions in social accountability and to emphasize that the social contract will be more powerful than the paradigm of the lone hero.

Lessons Learned

Forum member and Canadian Collaborative representative Sarita Verma led the discussion about the collaboratives’ work. She pointed

out that although the speakers identified a spectrum of approaches, strong leadership was a common theme that resonated with all the collaboratives. Without an enabled and mobilized leadership to recognize and advance a vision, the likelihood of change is minimal. Verma stated that the kind of disruptive innovations discussed at the workshop require courage, conviction, and an ability to embrace uncertainty and complexity while actively collaborating with others.

Verma emphasized the need for an imperative that drives the process. In Canada and India it was a government imperative, whereas in South Africa and Uganda (whose representative could not be present for this workshop) it was more of a social imperative. In each case, a critical point was reached where either the public or society through its government expressed the view that change was necessary. In her opinion, education and health are on the cusp of a “spring” that will be formed through public demand for change. Within the near future, she noted, health professions must be poised to address the demands of reform.

REFERENCES

ASPPH (Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health). 2006. Master’s degree in public health core competency model version 2.3. ASPH Educational Committee. www.asph.org (accessed September 14, 2013).

ASPPH. 2009. Doctor of public health (DRPH) core competency model version 1.3. ASPH Educational Committee. www.asph.org (accessed September 14, 2013).

Cruess, R., and S. Cruess. 2013. Professionalism and medicine’s social contract with society. Presented at the IOM workshop Establishing Transdisciplinary Professionalism for Health. Washington, DC, May 14.

Khurana, R. 2010. From higher aims to hired hands: The social transformation of American business schools and the unfulfilled promise of management as a profession. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univeristy Press.

U.S. Securites and Exchange Commission. 2013. The investor’s advocate: How the SEC protects investors, maintains market integrity, and facilitates capital formation. http://www.sec.gov/about/whatwedo.shtml (accessed September 14, 2013).

Werhane, P. 2013. Business ethics and management professionalism: What can be learned for transdisciplinary professionalism for health. Presented at the IOM workshop Establishing Transdisciplinary Professionalism for Health. Washington, DC, May 15.

Zimmerman, B. J., C. Lindberg, and P. E. Plsek. 1998. Edgware: Complexity resources for healthcare leaders. Dallas, TX: VHA Publications.