Going to the Gemba

ALBERTUS D. WELLIVER

Every so often we hear about businesses making dramatic comebacks, struggling out from a quagmire of red ink and scrambling up to world-class ground. While improvement in these cases is remarkable, the threat of imminent bankruptcy is usually the sole motivating force. On the other hand, the adrenalin seems to run dry in companies that have stayed successful over an extended period of time. When businesses are riding high, how can corporate leaders instill a sense of urgency among employees to improve their work? Or expressed another way, how can the “fat cats” in corporate America continue to savor the thrill of the hunt?

To find the answers to such questions, we need to take a look at some basic quality principles. At its core, continuous improvement has to do with the way we promote and manage change. In western businesses, we usually look for big changes that reap big results in a short time, especially innovations that lead to increases along the financial bottom line. In Japan and in other Pacific Rim countries, change in small increments is encouraged, often with better, longer-lasting results that are realized over the longer term. For those who are accustomed to gradual change, small improvements become a way of life that spills over into the way employees approach their work. That means, instead of making a great technological leap, then settling back until the next great upheaval, employees constantly make small adjustments to their work processes. This ongoing change, or kaizen, is described by Masaaki Imai (1986) as a people-oriented approach

that focuses more on the continuous process of improvement than the results of that effort.

The key to emphasizing the process is what Japanese managers call “going to the gemba.” In the manufacturing environment, an example of gemba, defined as any place where work is being done, is the factory floor. Here, managers can find facts and data that reveal where problems lie and ultimately, where to target improvements. By visiting the gemba for a firsthand look, managers do not have to rely on traditional communication lines for information, nor do they have to wonder whether the information was culled as it rose up through organizational layers.

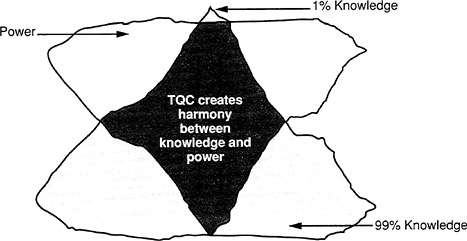

A descriptive model, “The Iceberg of Knowledge,” addresses the process of change in relation to the typical structure within an organization. The model has three elements, two of which are knowledge and power. Figure 1 shows that the distribution of knowledge in an organization is shaped like an iceberg, while the distribution of power can be described as an inverted iceberg. Technical details and awareness of problems that disrupt or slow down productivity reside with those in the gemba who do the practical work; yet power, or the ability to make changes, is embraced by top management. These managers must realize that issues are always perking near the bottom of the organization, even when the company's balance sheet looks healthy.

As a result of the imbalance between knowledge and power, high-level managers are generally not in touch with the realities of the production line,

FIGURE 1 “The Iceberg of Knowledge” addresses the process of change in relation to the typical structure within an organization.

and little decision-making authority is in the hands of those who actually have the facts and data.

Referring again to Figure 1 , what brings harmony to this disparity is a third element—total quality control (TQC). A basic element in any TQC effort is communication of data—specifically, statistics and information that describe a problem or establish a benchmark for improvement. Awareness of problems is what maintains the sense of urgency among managers to initiate changes that lead to improvement. But this type of knowledge is difficult to gain in large corporations. Sheer size can create organizational obstructions to the flow of information. Too often, the layers of management in an organization work as a filter, rather than a conduit, for facts and data.

If an organization is to successfully absorb change, whether it is brought on by improvements in technology or processes, a system must be in place that allows communication throughout all hierarchical levels.

Communication is initiated when senior management clearly states company goals and objectives for all to discuss and understand, then facts and data are invited directly from employees to help pinpoint where improvements are needed. Essentially, this exchange helps integrate knowledge and power.

As the flow of information increases, people with the practical knowledge will regularly help form organizational goals and objectives in a giveand-take process, which the Japanese call “catch-ball.” The manager would say, “Here's what I'd like you to do.” And the employee would respond by saying how he thought he could do it. They would toss ideas back and forth until they finally agreed. In America, we are more apt to play hardball. Top management says, “do it or else,” and if accomplishments fall short, the employee is hit with demerits.

At Boeing, we have initiated steps to establish a communication system that will bring together knowledge and power. At one fabrication plant, the equipment operators have been placed in charge of statistical process control.

That is quite a change from the way it used to be. The operators used to be judged by how many parts they turned out, regardless of accuracy. Wasted effort accumulated quickly using this method. For example, if a part has to go through n machining actions at different stations before it is complete, the operator at one station would usually produce these parts in lots and pass them on, without inspection, to the next station. If each machining task took an hour to perform, it would be n hours before the industrial engineer, who inspects parts only on completion, discovered that a hole was drilled a fraction off the mark. If the design requires a smaller variance, this process has not only escalated waste in material and time, but contributed to human frustration.

Now that Boeing better understands the value of the gemba, the operators have charge of the process. They collect data on every part they

manufacture, measuring where that part distributes within a range of variance. Because they inspect their own work, feedback is immediate. They can adjust their machine, and if it is not exact enough, they have the authority to shut it down until someone from maintenance can get the machine working up to standard.

What has happened at this factory simply follows human nature. When operators record data on a large tablet or board, it is readily visible not only to them, but to their supervisors. And the operator who uses a particular machine on the next shift can rely on that information to help set up the machine to begin his work. As the data accumulate, managers are able to identify problems and work with operators to tighten production variance gradually. Managers have entrusted their employees to think and plan their next move, not just act. This is when quality starts to improve. Moreover, when managers have access to data that come straight from the factory floor, they know where to focus their improvement efforts.

This change in approach at Boeing has resulted in a steady reduction in waste and rework. The rise in self-esteem among employees cannot be measured, but we know it is there. Employees have been given more freedom and power than ever before. They have the authority to stop the production process and call for maintenance. At the same time, they have the responsibility to make correct parts, collect data, and improve the way they work.

A second example of how Boeing is trying to merge knowledge and power occurred in late 1989. The engineers' union flatly rejected the contract offered by Boeing. Management was caught by surprise because we had been confident going into negotiations that the engineers were basically satisfied with the contract offer. How could the management be so remote from what was really going on? We simply did not have adequate facts and data.

There were no real lines of communication, so top management decided it was time to visit the gemba. We talked to engineers and their managers by the thousands, not telling them anything, but asking what was on their minds. We learned a lot. As a result, Boeing will be changing the way it handles compensation, education, career enhancement, and its performance measurement system. The next step is communicating to the entire engineering organization what we heard, and what we plan to do about it. Then, we will go back to the gemba to find out if we are on the right track. We are going to follow that up with an employee survey to check employee feedback on a broader scale. This effort is so important that top management is going to measure its own success based on those survey results. This method of benchmarking is a significant departure from previous efforts.

Boeing is slowly learning that employee motivation grows naturally out

of good communication and a balance of knowledge and power. Our biggest challenge is to instill this philosophy and approach throughout the company. Managers are accustomed to having more control over the processes, but they do not realize they will have much more control over the quality of their products or services if they let go of some of the decision making. Going to the gemba has taught us that letting go is easier than most people dare to think.

We are also learning that managers must look for problems with vigilance, gaining an understanding of the real issues and problems by poring over facts and data. It is a tough job. But once the hidden problems are revealed, managers start to realize that the appearance of a smoothly operating organization can be deceptive. Once they set up a process to find out about concerns and problems below the tip of the iceberg, the gemba becomes a continuous source of information and inspiration for change. It is this process that keeps a company on the urgent edge of continuous improvement.