![]() INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE

INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE

OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES

Advising the nation • Improving health

Spread, Scale, and Sustainability

in Population Health—Workshop in Brief

The Institute of Medicine’s Roundtable on Population Health Improvement engages roundtable members and other experts, practitioners, and stakeholders from health and nonhealth sectors in exploring what is needed to improve population health. Population health refers to “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group” (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003). The roundtable understands population health outcomes as a product of multiple determinants of health, including medical care, public health, genetics, behaviors, social factors, and environmental factors. The roundtable intends to catalyze urgently needed action toward a stronger, more healthful, and more productive society.

On December 4, 2014, the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement held its 10th workshop in New York City. The workshop, titled “Achieving Meaningful Population Health Outcomes: A Workshop on Spread and Scale,” focused on the spread, scale, and sustainability of strategies to improve population health in a variety of contexts and sectors. The workshop explored: (1) the different meanings of spread and scale; (2) what could be learned about a variety of approaches to the spread and scale of ideas, practices, programs, and policies; (3) how users measure whether their strategies of spread and scale were effective; and (4) how to accelerate a focus on spread and scale strategies in population health. Keynote speaker Anita McGahan, associate dean of research, professor, and Rotman Chair in Management, Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, challenged participants to consider what it means to achieve spread, scale, and sustainability in North America and other parts of the globe. Joe McCannon, cofounder of the Billions Institute and a consultant to The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, encouraged the audience to consider the characteristics that define local programs that have successfully achieved scale.

The workshop also featured three panels, one focusing on the health sector, one on nonhealth sectors, and one on tobacco control. Speakers presented case studies of evidence-based initiatives in childhood health, environmental justice, global health, homelessness, and Medicaid and Medicare. Throughout the day, participants focused on the practical aspects of how to spread and scale ideas, programs, practices, and policies, while frankly discussing their experiences with the barriers and successes of effectively improving population health outcomes.

Design for Success

In her opening keynote, McGahan suggested that in order to achieve either population health or what she called “population resilience,” strategies should be developed to measure outcomes and make sure that what is being done is actually working. McGahan stated, “The easiest way to fail in spreading, scaling, and sustaining population resilience is trying to spread interventions that are not effective, to scale nonscalable activities, and to try to sustain outcomes that patients don’t want.” Effective interventions require figuring out how to spread, scale, and sustain outcomes that are desired at the level of the individual, community, and population, she said.

“Why is it so difficult for us to take what is sound, what has worked locally, to a larger scale?” asked McCannon. He emphasized that inertia, competition, fear, and conflicting sets of values can undermine change. He offered a list of attributes that differentiate typical from exceptional initiatives, including a bias toward getting started with explicit, time-bound aims rather than waiting for consensus. Other attributes are getting people into the field to learn what works best, collecting data to regularly adapt methods, and developing a detailed understanding of the population in order to more efficiently and effectively maximize impact.

McCannon noted that exceptional social justice initiatives are designed for success and scale from the outset. McGahan and McCannon emphasized the need to control costs and introduce economies of scale over time. McGahan and her research team study innovation in global health. Scaling organizations involves investing in fixed costs and creating fixed infrastructure, she said, so larger numbers of people can be served with diminishing marginal costs over time. Rashad Massoud of University Research Company, LLC, noted that for the USAID ASSIST (Applying Science to Strengthen and Improve Systems) projects he directs, designing for success means building the infrastructure and capacity from the start so that country representatives can take over and be successful when the outside consultants leave. In Tver Oblast, Russia, for example, Massoud and his colleagues helped the government reduce the mortality rate resulting from neonatal and infant hyaline membrane disease. Six years after they took the project from pilot to scale-up and turned it over to local colleagues, the reduction in the mortality rates were twice as good as when they were there, he said.

Demonstration and Evaluation

Before starting demonstration projects, Steven Kelder of the University of Texas School of Public Health and co-creator of the Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH) said, he and his colleagues conducted studies evaluating the impact of their interventions on children’s health in Dallas schools; for example, they ”piggybacked” on existing fitness standard testing to show that schools and districts that implemented their interventions at a higher rate showed a stronger effect on health outcomes than other schools. Kelder noted that research has to be conducted to create an evidence base that is persuasive to potential funders and partners.

Darshak Sanghavi of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) suggested that if the funding is available, an independent and well-designed evaluation be conducted prior to the intervention. Sanghavi noted that for CMS, if interventions are not designed in a way that demonstrates that their payment policies are responsible for cost reductions or quality improvements in health care or Medicare, the data are unlikely to be persuasive.

McCannon and Massoud noted the importance of starting small with demonstration pilot projects before scaling up. Massoud cautioned against starting an initiative on a large scale unless those involved are certain the initiative will work. Start small, be deliberate about the choices made, and select the best staff possible, he said. Massoud also cautioned against replication as a method of spread, stating that it was slower than using adaptive or a hybrid of methods, such as collaborative learning and improvement, extension agents, and wave sequence (Massoud and Mensah-Abrampah, 2014; Massoud et al., 2006, 2010).

Data for Learning and Adaptive Spread

Change requires gathering relevant data and using ongoing evaluation. McCannon suggested that the hallmark of a successful large-scale change strategy is to start with a formative evaluation that provides timely data that can be used to make adjustments to strategy on a weekly basis. McCannon noted that a “learning system” both supplies people with data that allow them to change and improve themselves and equips them with the means to collect data in order to drive change (Massoud et al., 2010). For example, Community Solutions’ 100,000 Homes Campaign used a process inspired by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, said Linda Kaufman of Community Solutions, which helped them to understand how to use demonstration projects before scaling up in an iterative learning process (Massoud et al., 2006). Once they had developed a housing first model, Community Solutions starting spreading it around the country. Although they did not attempt to replicate what they did to reduce homelessness in Times Square, they worked with clear goals and timelines to measure success. They used boot camps to teach people how to reduce homelessness, the lessons of which they could take home and adapt to their own communities. Kaufman and McCannon both noted the importance of communities being actively involved through hands-on application so they feel empowered to take on the initiative. Kaufman added that Community Solutions was able to get data from these different communities by creating a competition to reach benchmarks

(reducing chronic homelessness by 2.5 percent per month), which contributed to the communities’ success of reaching their goals and providing timely data for adapting strategies.

Reaching and Monitoring the Population

McCannon said that it is essential to know who the population is, not only in terms of the innovators, adopters, and laggards but also in terms of segments of the population by readiness and geography. McGahan and her research team think of spread as reach and consider ways to ensure that interventions are actually reaching everybody in a population in need. Massoud and McCannon noted that extension agents are a way to reach people in remote geographic areas because they travel from site to site and serve as the community’s “connective tissue.” Through these mobile people, McCannon said, the data, problems, challenges, and experiences of the hard-to-reach population are collected (Massoud et al., 2010).

In practice, McGahan said, there are often tradeoffs between spread, scale, and sustainability. One way to break tradeoffs is through the use of large amounts of data and monitoring. People at the margins often hide. By implementing national health registration cards, for example, people have access to different individual and community resources, and the health system is able to track people at the level of individuals and populations, thus enabling the monitoring necessary to effectively spread and scale health interventions, as well as sustain outcomes.

Partnerships and Relationships

Achieving scale and spread often requires partners. Sanghavi suggested involving partners at an early stage so they have input and feel that they are participating in part of the intervention’s design. Kelder suggested using a snowball sampling strategy to find innovators and adopters early in the process. Kelder and colleagues met with local officials and innovators throughout Texas, and then other districts became aware of what they were doing and contacted them, and that is how their work evolved. Kelder and his team were purposeful about presenting and spreading the ideas and data they had collected on the efficacy of the programs in Texas, and then they built relationships with people outside the state through professional organizations and local affiliates to help facilitate the spread of CATCH.

At West Harlem Environmental Action, Inc. (WE ACT), Ogannaya Dotson-Newman, the director of environmental health, said, the staff provides training and empowerment to poor and low-income groups and communities of color so they are prepared to advocate for themselves and take steps to limit their exposure to toxins. WE ACT translates community concerns into advocacy and research. One way they do this is by partnering with researchers at academic institutions who help them to develop innovative solutions to problems. WE ACT takes the scientific information produced by their academic partners and translates it into understandable language that can be used by communities to create and advocate for better policies.

Dan Herman of Hunter College and the Center for the Advancement of Critical Time Intervention (CTI) said that “we do not really have the capacity, and I think most intervention developers do not have the capacity” to scale up alone. He explained that CTI is an evidence-based model for helping homeless people during “high-risk transition periods” to navigate the complex social service environment with the explicit goal of a limited intervention to prevent people from cycling back into homelessness, incarceration, or rehospitalization. To do what is needed for their clients, Herman said, they use “essentially a partnership strategy” by working with organizations to train the trainers and try to connect with advocacy groups and policy makers.

In another example, Michelle Larkin of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation noted that in tobacco control, nontraditional partners can help to accelerate the movement by adding voices and credulity in a way that others cannot. The Legacy Foundation partnered with hotel chains to make hotels 100 percent smoke free, said Cheryl Healton of New York University. Sally Herndon of the North Carolina Division of Public Health worked with the Department of Housing and Urban Development to provide incentives to make affordable housing smoke free. Initially there was resistance, but gradually the business and banking communities showed support for giving tax credits to affordable properties that open smoke free.

If you are interested in moving the needle in population health, you have to raise money, commented Kelder. In Texas, for example, vast differences exist between the wealthy communities in Dallas and the poor communities in the border areas of Texas. For CMS, added Sanghavi, a significant barrier to scaling is that the communities with the most resources, “durable, highly invested institutions,” apply for and win funding (e.g., innovation grants for community health), which then leaves large areas of the country without those types of innovative solutions. He noted that the truly innovative health centers struggle to find sustainable funding. CMS is only one payer, and a core challenge is getting private payers to partner with CMS to pay for innovation.

A common challenge to scaling up is human capital. Kelder noted that the recent recession resulted in the loss of personnel who were familiar with CATCH, creating problems with the implementation and maintenance of CATCH programs. Massoud added that when extremely capable staff members, often called champions, who worked on demonstration pilots are transferred during the process of scaling up, problems can occur, and he emphasized the need to retain the people who have the most knowledge and experience.

In social services, Herman suggested that one challenge is the inadequate infrastructure to support the “uptake of evidence-based models.” One of his team’s concerns is how their dissemination efforts will be sustained. Herman does not see the support for “a thoughtful, effective business model or infrastructure to support spread” existing in the social services field. He emphasized that not everyone has a charismatic leader, which can be a critical component of success. Dotson-Newman noted that there has to be sustained financial investment to get people to push forward or to even be in a position to develop a business model, theory of change, or particular spread approach.

Another challenge, Dotson-Newman said, is that the struggle to end racism and classism is ongoing. Given current and historical injustices, she said, it will take interrupting and disrupting the status quo to bring things to scale and see measurable results. She noted that most organizations do not have WE ACT’s budget and work on a case-by-case basis. Jeannette Noltenius, former national director of the National Latino Tobacco Control Network, said that scaling up the impact of smoke-free policies in racial, gender, and ethnic minority communities by disseminating information and mobilizing support is difficult to do when there is not enough money at the local level to partner with states or other stakeholders. Noltenius and Brian King of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention commented that a lack of data that are relevant to a particular community can also add to the challenge of making equitable interventions. People get engaged when they see themselves as part of the solution. Noltenius added that it is critical to get data to understand the “diversity within disparities.” In New York City, for example, Puerto Ricans, especially women, have some of the highest smoking rates, and yet Latinos in general have some of the lowest. Advocates need to understand how low smoking rates for a population can disguise higher rates of a subgroup.

The Challenges of Maintaining the Momentum and Sustaining Impact: The Example of Tobacco Control

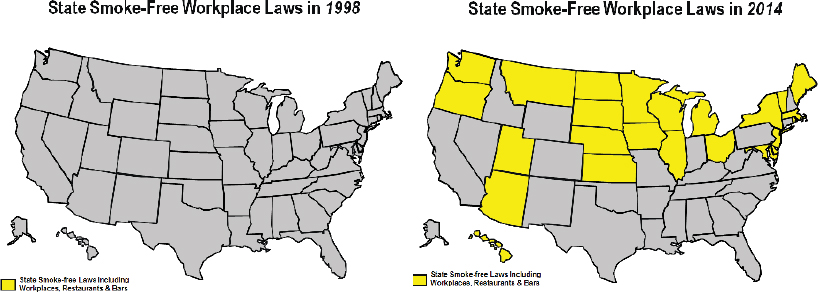

Larkin showed maps of the spread of the 100 percent smoking-free laws and policies that touch bars, restaurants, and workplaces from 1998, the year of the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, to 2014 (see figure).

Tobacco control measures that focused specifically on clean indoor air spread fairly rapidly, aside from in the southern United States. As Larkin, Herndon, King, and Noltenius emphasized, although the rate of smoking dropped from 42 percent to 18 percent of the population because of changing social norms, there continues to be inequitable spread and implementation of interventions across states and among marginalized populations. Noltenius expressed concern for the future, because changing demographics means an increase in young Latinos and Asian Americans, who may not be the focus of tobacco control campaigns. She added that while there has certainly been progress, “we have to think about who we leave behind.”

FIGURE State smoke-free workplace laws, 1998 and 2014.

SOURCE: Michelle Larkin, workshop presentation, December 4, 2014.

The biggest barrier to implementation and spread of what works (100 percent smoke-free policies, tobacco price increases, cessation access, and hard-hitting media campaigns), King said, was that states were no longer using the billions of dollars from the Master Settlement Agreement for tobacco control. Noltenius commented that California initially funded 160 community-based organizations at the height of national efforts to control tobacco, and now there are 34. Healton stated that the biggest challenge is that when people stop smoking as a result of the success of campaigns, the tobacco industry responds forcefully, and that makes it harder to have a sustained impact. Healton, who led the Legacy Foundation’s truth® Campaign that targeted youth tobacco use with graphic advertisements, was highly successful at reducing youth smoking. At least 22 percent of the decline in youth smoking in the United States between 2000 and 2004 could be attributed to Legacy efforts, Healton said. The ads were familiar to 90 percent of adolescents, and 75 percent could describe at least one ad. Legacy was most influential in reducing images of smoking in movies, she noted, and that led to the biggest pushback from the tobacco industry.

Several panelists mentioned a range of methods used by the tobacco industry in response to tobacco-control efforts. One strategy in recent years has been to support the implementation of state and federal laws to preempt the ability of local jurisdictions to implement tobacco-control policies. Larkin noted that preempting the implementation of local policies is designed specifically by the industry to stop movement building.

Spreading Stories, Spreading Values, Building a Movement

Several speakers emphasized the centrality of spreading values, beliefs, and stories. McGahan, Massoud, McCannon, Kelder, and Kaufman all emphasized the importance of considering the values and beliefs of the individuals and communities involved in change initiatives. Beliefs and values are the “ultimate in platforms” of spread and scale, McGahan stated, because there is no cost to setting them up. By cultivating and spreading beliefs and building marginal costs, it is possible, she said, to create “a pandemic of health.” As McCannon said, “What we are really doing if we are successful at having scale is we are spreading culture, and we are spreading values.”

Herndon provided one example of spreading culture. She described how school systems that were 100 percent tobacco free served as a starting point for building a movement. As school systems’ stories were collected and shared at organized breakfasts, Herndon and her colleagues were able to expand their reach, particularly after they received Master Settlement Agreement funding. Because the majority of smokers start smoking at age 12 to 14, Herndon and her colleagues wanted to change the social norms of kids smoking. At a meeting with the governor, high school students from throughout the state reported that they learned to smoke from teachers, so all

schools needed to be tobacco free. After working with a pediatrician legislator to get a tobacco-control bill passed, Herndon and colleagues were able to work locally to get all schools 100 percent tobacco free. As more partners came on board, they created the momentum and movement that spread from hospitals to mental health and substance-abuse facilities and prisons. It has taken 20 years, but in 2010 North Carolina became the first southern state and only tobacco-producing state to make restaurants and bars 100 percent smoke free. Challenges remain. They are still working to exercise local authority, after successfully challenging a portion of a preemptive law, to ban smoking in government buildings and grounds and other public places.

Accelerating Spread and Scale in Population Health

George Isham of HealthPartners, Inc., asked McCannon his thoughts on when to initiate scaling up and what would be the equivalents of 100,000 homes or 100,000 lives (an initiative of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement) for the population health field’s goals of prolonging life expectancy and increasing equity. McCannon suggested that they start in about 6 months, after conducting brief deliberations, selecting interventions, and calculating their impact on life expectancy. He noted that a probable path forward in population health is to identify the depth of the evidence base, the number of people affected, the demand, and the potential funding. A cluster of possible practices should be identified to start with and adopt and then set goals to reach within a particular time frame, such as the 2030 targets for life expectancy Isham mentioned, as recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2012). McCannon emphasized again the wisdom of starting small and developing a learning system that empowers people by providing them with the ability to collect data in real time that they can use to change and improve. He noted that although developing a measurement strategy was important, even more vital to success is figuring out who the organizations and core people are who will do the work to spread and scale improved population health. ![]()

American Legacy Foundation

http://www.legacyforhealth.org/?o=4075#

Billions Institute

http://www.billionsinstitute.org

CATCH (Coordinated Approach to Child Health) http://catchinfo.org

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) http://www.cdc.gov

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) http://www.cms.gov

Community Solutions’ 100,000 Homes Campaign http://100khomes.org

CTI (Critical Time Intervention) http://sssw.hunter.cuny.edu/cti

National Latino Tobacco Control Network http://www.indianalatino.com/NLTCN/default.asp

North Carolina Tobacco Prevention and Control http://www.tobaccopreventionandcontrol.ncdhhs.gov

URC (University Research Co., LLC) http://www.urc-chs.com

USAID ASSIST Project https://www.usaidassist.org

WE ACT for Environmental Justice http://www.weact.org

References

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2012. For the public’s health: Investing in a healthier future. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kindig, D., and G. Stoddart. 2003. What is population health? American Journal of Public Health 93(3):380-383.

Massoud, M. R., and N. Mensah-Abrampah. 2014. A promising approach to scale up health care improvements in low- and middle-income countries: The wave-sequence spread approach and the concept of the slice of a system. F1000Research 3:100.

Massoud, M. R., G. A. Nielsen, K. Nolan, M. W. Schall, and C. Sevin. 2006. A framework for spread: From local improvements to system-wide change. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

Massoud, M. R., K. L. Donohue, and C. J. McCannon. 2010. Options for large-scale spread of simple, high-impact interventions. Bethesda, MD: University Research Co., LLC. http://www.isqua.org/docs/education-/options-for-large-scale-spread-ofsimple-high-impact-interventions-910.pdf?sfvrsn=0 (accessed March 16, 2015).

Roundtable on Population Health Improvement

George Isham (Co-Chair)

HealthPartners, Inc.

David A. Kindig (Co-Chair)

University of Wisconsin

Terry Allan

National Association of County and City Health Officials and Cuyahoga County Board of Health

Catherine Baase

The Dow Chemical Company

Gillian Barclay

Aetna Foundation

Raymond J. Baxter

Kaiser Permanente

Raphael Bostic

University of Southern California

Debbie I. Chang

Nemours

Carl Cohn

Claremont Graduate University

George R. Flores

The California Endowment

Jacqueline Martinez Garcel

New York State Health Foundation

Mary Lou Goeke

United Way of Santa Cruz County

Marthe R. Gold

New York Academy of Medicine and City College of New York

Garth Graham

Aetna Foundation

Peggy A. Honoré

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Robert Hughes

Missouri Foundation for Health

Robert M. Kaplan

National Institutes of Health

James Knickman

New York State Health Foundation

Paula Lantz

The George Washington University

Michelle Larkin

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Thomas A. LaVeist

Johns Hopkins University

Jeffrey Levi

Trust for America’s Health

Sarah R. Linde

Health Resources and Services Administration

Sanne Magnan

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement

Phyllis D. Meadows

University of Michigan

Judith A. Monroe

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

José Montero

Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and New Hampshire Division of Public Health Services

Mary Pittman

Public Health Institute

Pamela Russo

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Lila J. Finney Rutten

Mayo Clinic

Brian Sakurada

Novo Nordisk Inc.

Martin José Sepúlveda

International Business Machines Corporation

Andrew Webber

Maine Health Management Coalition

Roundtable Staff

Alina B. Baciu

Director

Colin F. Fink

Senior Program Assistant

Amy Geller

Senior Program Officer

Lyla Hernandez

Senior Program Officer

Andrew Lemerise

Research Associate

Darla Thompson

Associate Program Officer

Rose Marie Martinez

Director, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice

DISCLAIMER: This workshop in brief has been prepared by Darla Thompson, rapporteur, as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the authors or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies.

REVIEW: To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this workshop in brief was reviewed by Drew A. Harris, Thomas Jefferson University School of Population Health, and Marie W. Schall, Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Chelsea Frakes, Institute of Medicine, served as review coordinator.

This workshop was partially supported by contracts between the National Academy of Sciences and The Aetna Foundation (#10001504), The California Endowment (20112338), Kaiser East Bay Community Foundation (20131471), Kresge Foundation (101288), Missouri Foundation for Health (12-0879-SOF-12), New York State Health Foundation (12-01708), and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (70555). The views presented in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations or agencies that provided support for the activity.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit www.iom.edu/spreadhealth.

For more information about the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, visit www.iom.edu/pophealthrt or e-mail pophealthrt@nas.edu.